On the Authenticity of Two Presumed Paleolithic Female Figurines from the Art Market

Abstract

1. Introduction

Provenance of the Figurines and Acquisition History

2. Materials and Methods

- (a)

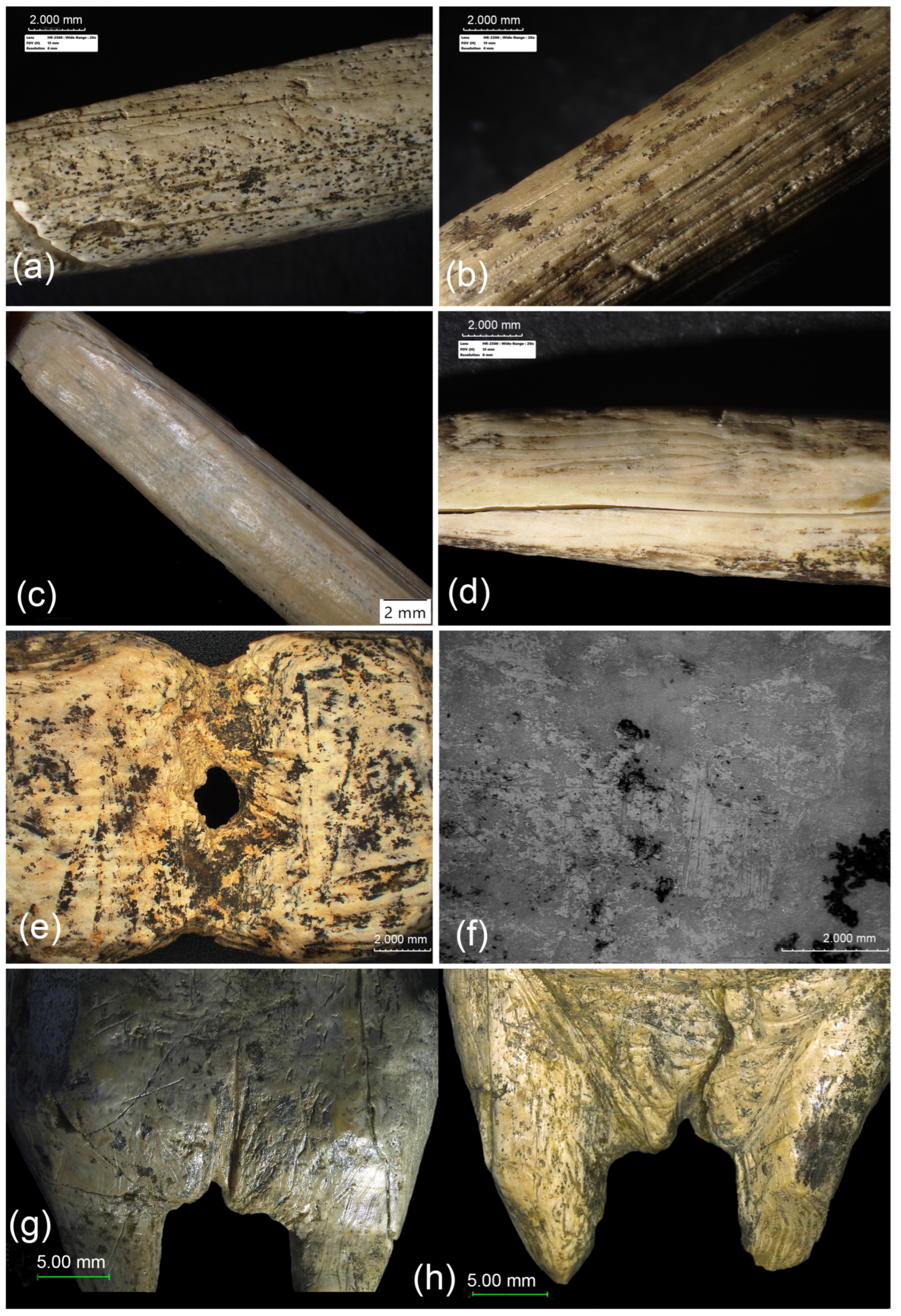

- Three modern ivory replicas depicting the well-known archaeological figurines of the “horse” (Vogelherd Cave, Germany) [1], the “lion head” (Vogelherd, Germany) [2], and “la dame à la capuche de Brassempouy” (Brassempouy, France) [3]. The figurines were produced by the ivory carver Bernhard Röck in his atelier in Erbach im Odenwald (Germany) with modern tools used to carve ivory (e.g., dental tools). The operational sequence for the manufacture of these ivory figurines included the use of a Dremel (multifunctional tool), gear grinders, a polishing machine, and beeswax on a rotating cotton belt to finish the polishing procedure. With the aim of correlating different types of traces to specific tools used during the carving process, we observed the figurines at two different working stages: before and after polishing.

- (b)

- A tusk piece of a mammoth from the Siberian permafrost from Bernhard Röck’s stock which was cut in half with an Elektra Beckum BAS 500 Metabo band saw Metabo, Nürtingen, Germany.

- (c)

- Two replicas of double and single perforated ivory beads (see examples in [4]) carved with stone tools by the Archaeotechnician Rudolf Walter at the University of Tübingen.

- (d)

- Six worked archaeological ivory pieces: two broken ivory points, three ivory rods, and a single perforated ivory bead from the Aurignacian layers IV and V, respectively, of the cave sites Hohle Fels (Schelklingen, Germany) and Vogelherd (Niederstotzingen, Germany).

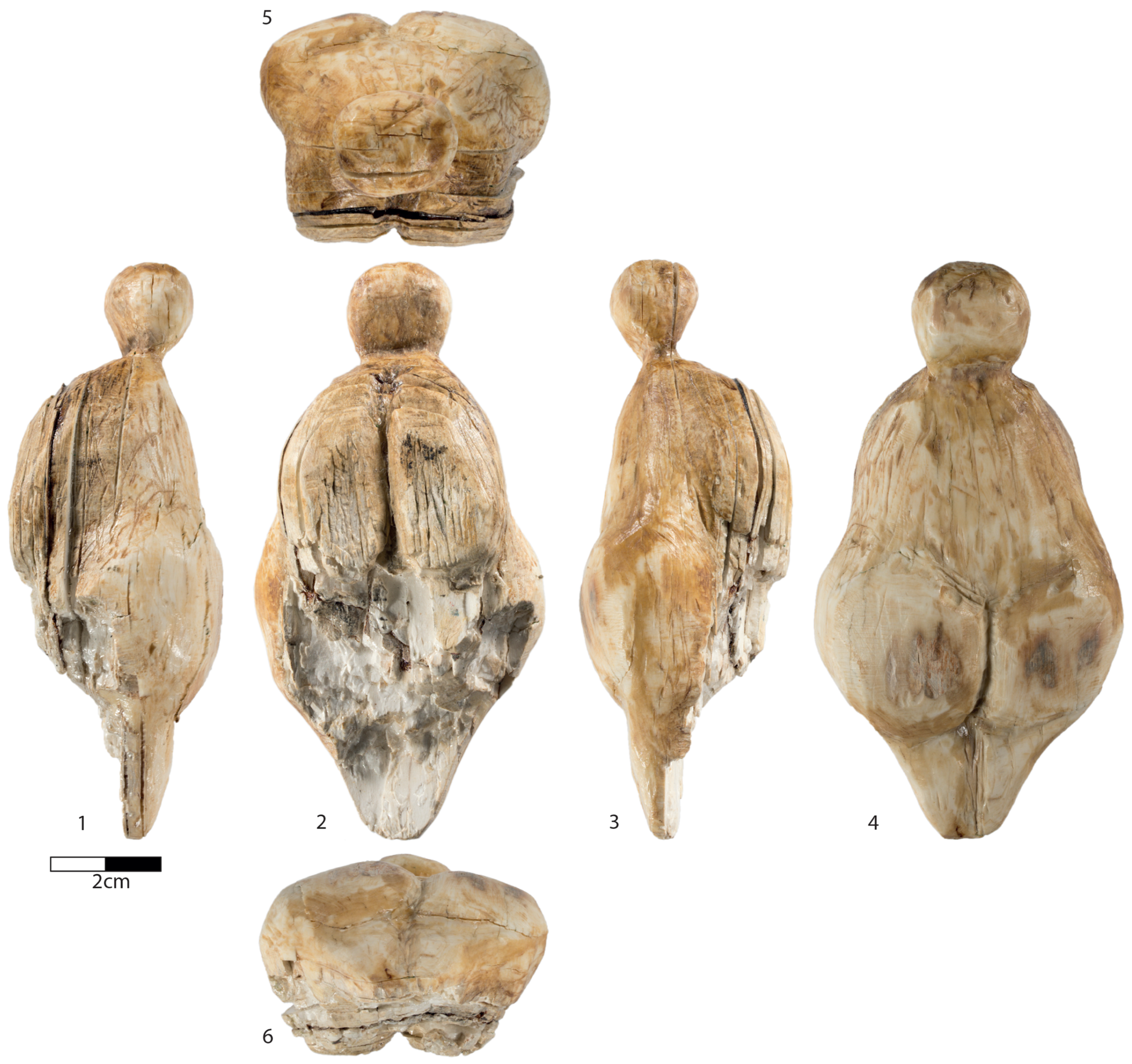

2.1. Description of the Two Figurines

2.2. Comparative Findings as Models

3. Results

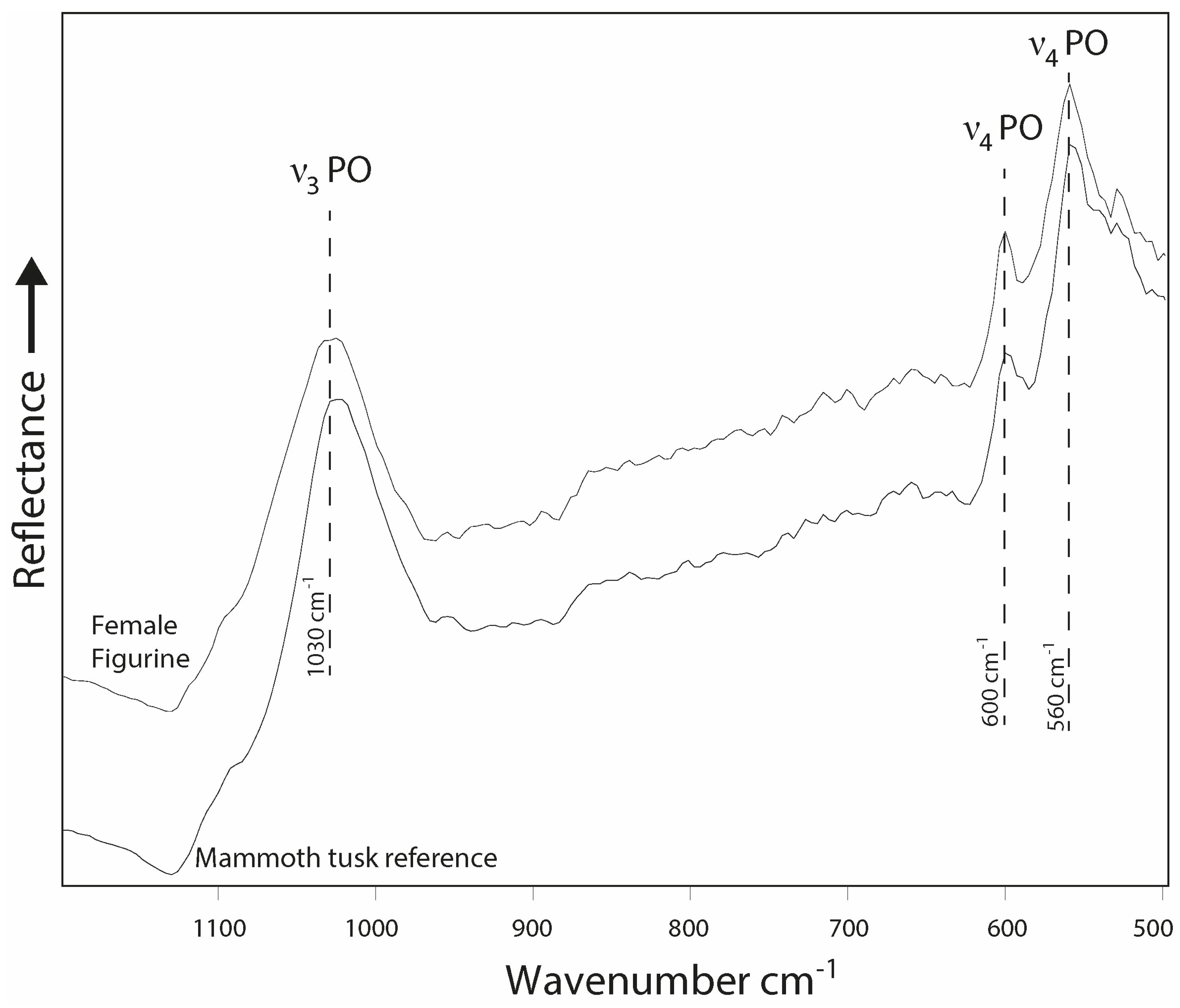

3.1. Spectroscopic Analysis

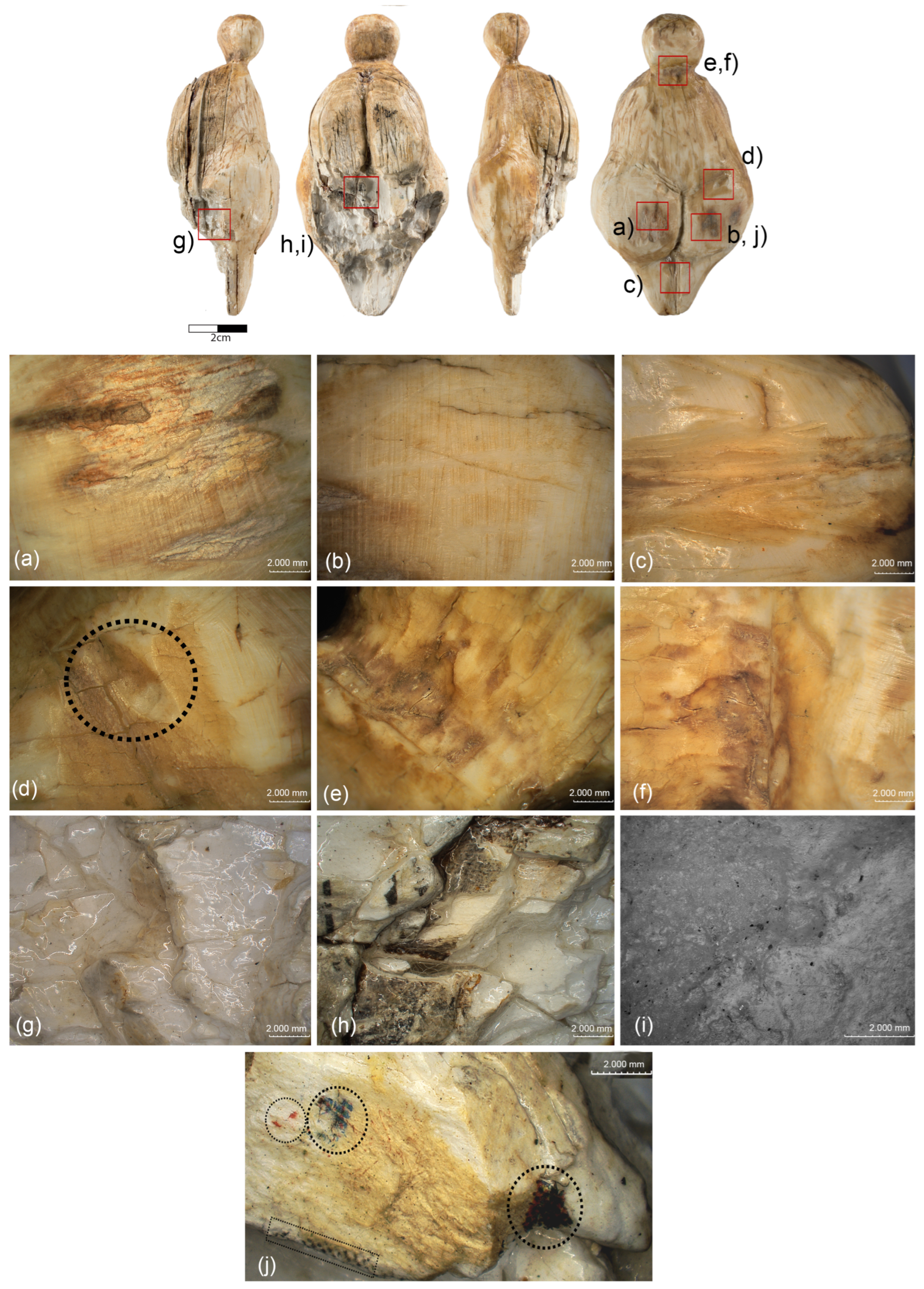

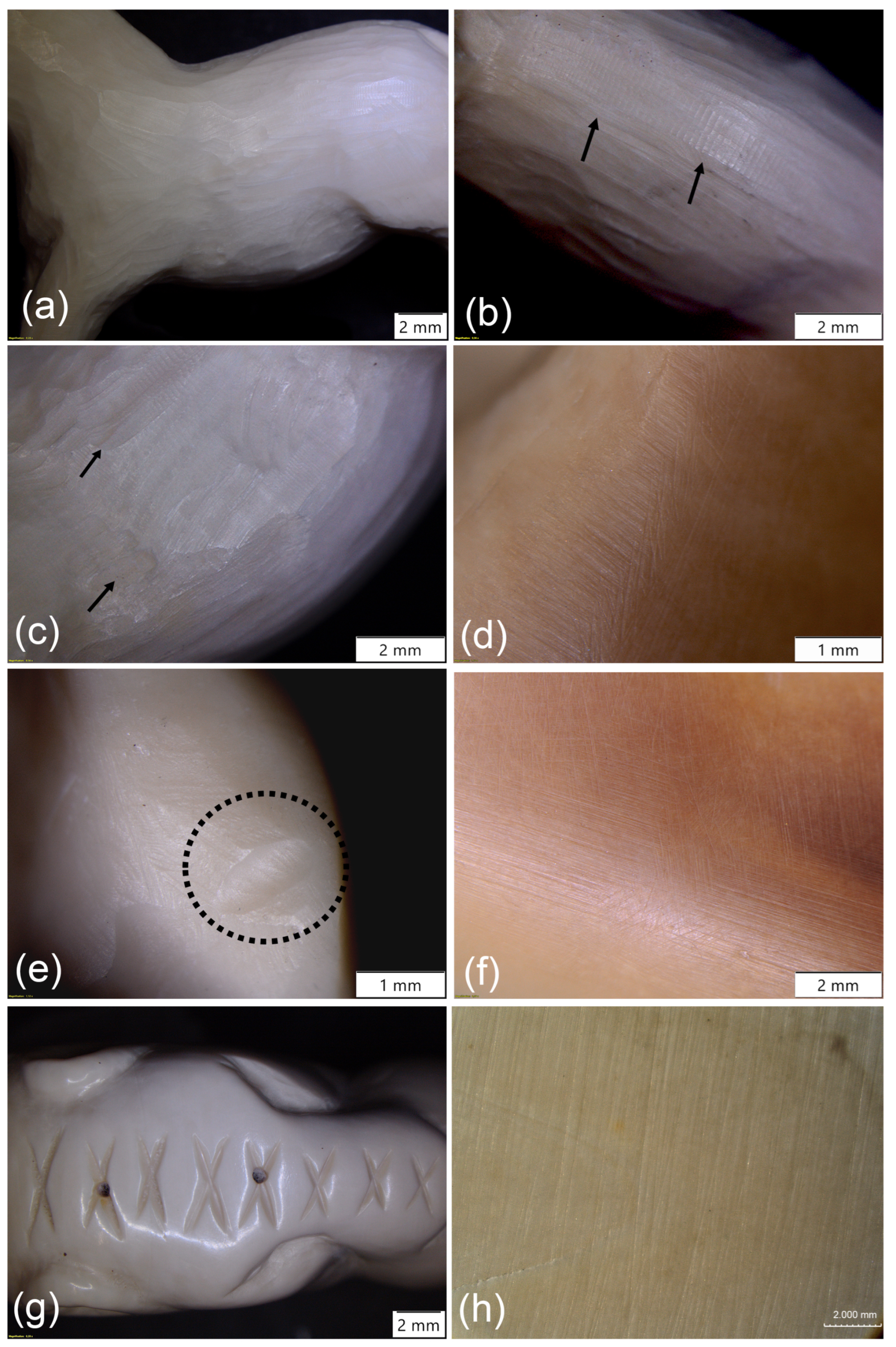

3.2. Optical Observations and Production Wear

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riek, G. Die Eiszeitjägerstation am Vogelherd im Lonetal; Heine Verlag: Tübingen, Germany, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Dutkiewicz, E. Zeichen: Markierungen, Muster und Symbole im Schwäbischen Aurignacien; Kerns Verlag: Tübingen, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Piette, É. La station de Brassempouy et les statuettes humaines de la période glyptique. L’Anthropologie 1895, 6, 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, S. Schmuckstücke—Die Elfenbeinbearbeitung im Schwäbischen Aurignacien; Kerns Verlag: Tübingen, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, T.J.; Schmidt, P. The unique laurel-leaf points of Volgu document long-distance transport of raw materials in the Solutrean. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2022, 14, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roebroeks, W.; Mussi, M.; Svoboda, J.; Fennema, K. (Eds.) Hunters of the Golden Age: The Mid Upper Palaeolithic of Eurasia 30,000–20,000 BP; Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia; University of Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Otte, M. (Ed.) Les Gravettiens; Éditions Errance: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, L. Le Gravettien ancien d’Europe central revisité: Mise au point et perspectives. L’Anthropologie 2012, 116, 609–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlopachev, G.A. Bepxнuŭ naлeoлum: Oɓpaɜы, cuмвoлы, ɜнaκu: Каmалoг npeдмemoв ucκуccmвa мaлыx фopм u унuκaльныx нaxoдoκ вepxнeгo naлeoлuma uɜ apxeoлoгuчecκoгo coɓpaнuя MAЭ РАH. Рeдaκmop/Оmвemcmвeнныŭ peдaκmop: Хлonaчeв Γ.A. Upper Paleolithic: Images, symbols, signs: Catalog of Small Forms Art Objects and Unique Finds of the Upper Paleolithic from the Archaeological Collection of the MAE RAS; Khlopachev, G.A., Ed.; Kunstkamera: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bosinski, G. Die Große Zeit Der Eiszeitjäger. Europa zwischen 40.000 und 10.000 v. Chr. Jahrb. Des Röm. Ger. Zentralmuseums 1987, 34, 3–139. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble, C. Social Context for European Palaeolithic Art. Proc. Prehist. Soc. 1991, 57, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delporte, H. Image de la Femme dans l’Art Préhistorique; Édition Picard: Paris, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Neruda, P.; Hamrozi, P.; Patáková, Z.; Pyka, G.; Zelenka, F.; Hladilová, S.; Oliva, M.; Orságová, E. Micro-computed tomography of the fired clay venus of Dolní Věstonice (Czech Republic). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2024, 169, 106034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, C.; Deneuve, É.; Fagnart, J.-P.; Coudret, P.; Antoine, P.; Peschaux, C.; Lacarrière, J.; Coutard, S.; Moine, O.; Guérin, G. Premières observations sur le gisement gravettien à statuettes féminines d’Amiens-Renancourt 1 (Somme). Bull. Société Préhistorique Fr. 2017, 114, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klíma, B. Les figurations paléolithiques féminines en Moravie. In La Dame de Brassempouy; Delporte, H., Ed.; ERAUL 74: Liège, Belgium, 1995; pp. 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy, D. Fragments D’images, Images de Fragments: La Statuaire Gravettienne, du Geste au Symbole. Ph.D. Thesis, Dissertation Aix-Marseille 1. Universite de Provence–Aix-Marseille I, Marseille, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gvozdover, M.D. The typology of female figurines of the Kostenki palaeolithic culture. Sov. Anthropol. Archaeol. 1989, 27, 32–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, S. Eine neue Venusstatuette vom jungpaläolithischen Fundplatz Dolní Vĕstonice (Mähren). Jahrb. Des Röm. Ger. Zentralmuseums 2011, 55, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bisson, M.; Bolduc, P. Previously Undescribed Figurines from the Grimaldi Caves. Curr. Anthropol. 1994, 35, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussi, M.; Cinq-Mars, J.; Bolduc, P. Echoes from the Mammouth Steppe: The case of the Balzi Rossi. In Hunters of the Golden Age. The Mid Upper Palaeolithic of Eurasia 30,000–20,000 BP.; Roebroeks, W., Mussi, M., Svoboda, J., Fennema, K., Eds.; Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia; University of Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 31, pp. 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Gvozdover, M.D. Art of the Mammoth Hunters: The Finds from Avdeevo; Oxbow Monograph 49: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Antl-Weiser, W. Die Frau von W.: Die Venus von Willendorf, Ihre Zeit Und Die Geschichte(n) Um Ihre Auffindung; Naturhistorisches Museum: Wien, Austria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, G.W.; Lukeneder, A.; Harzhauser, M.; Mitteroecker, P.; Wurm, L.; Hollaus, L.-M.; Kainz, S.; Haack, F.; Antl-Weiser, A.; Kern, P. The microstructure and the origin of the Venus from Willendorf. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Absolon, K. The Venus of Vestonice—Faceless and “visored”. Illus. Lond. News 1929, 175, 936–938. [Google Scholar]

- Nerudová, Z.; Vaníčková, E.; Tvrdý, Z.; Ramba, J.; Bílek, O.; Kostrhun, P. The woman from the Dolní Vestonice 3 burial: A new view of the face using modern technologies. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 2527–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlopachev, G.A.; Vercoutère, C.; Wolf, S. Les statuettes féminines en ivoire des faciés gravettiens et post-gravettiens en Europe centrale et orientale: Modes des fabrication et de représentations. L’Anthropologie 2018, 122, 492–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer-Maresch, C. Zum Neufund einer weiblichen Statuette bei den Rettungsgrabungen an der Aurignacien-Station Stratzing/Krems-Rehberg, Niederösterreich. Germania 1989, 67, 551–559. [Google Scholar]

- Conard, N.J. A female figurine from the basal Aurignacian of Hohle Fels Cave in southwestern Germany. Nature 2009, 459, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosinski, G.; Fischer, G. Die Menschendarstellungen von Gönnersdorf der Ausgrabung von 1968; Gönnersdorf, Bd. I.; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Höck, C. Die Frauenstatuetten des Magdalénien von Gönnersdorf und Andernach. Jahrb. Des Röm. Ger. Zent. Mus. 1999, 40, 253–317. [Google Scholar]

- Bosinski, G. Femmes Sans Tête: Une Icône Culturelle Dans L’Europe de la Fin de L’époque Glaciaire; Édition Errance: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Simonet, A. Brassempouy (Landes, France) ou La Matrice Gravettienne de L’Europe; ERAUL 133: Liège, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zamiatnine, S.N. La station aurignacienne de Gagarino et les donneés nouvelles qu’elle fournit sur les rites magiques des chasseurs quaternaires. In Bulletin de L’Académie D’Histoire de la Culture Matérielle; Les Éditions d’État: Moscow, Russia; Leningrad, Russia, 1934; Volume 88. [Google Scholar]

- Abramova, Z.A. Paleolithic Art in the U.S.S.R. Arct. Anthropol. 1967, 4, 1–179. [Google Scholar]

- Lalanne, J.-G. Découverte d’un bas-relief à représentation humaine dans les fouilles de Laussel. L’Anthropologie 1911, 22, 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Neeb, E.; Schmidtgen, O. Eine altsteinzeitliche Freilandraststätte auf dem Linsenberg bei Mainz. Mainz. Z. 1924, 17/19, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, J. Gravettien-Freilandstationen im Rheinland: Mainz-Linsenberg, Koblenz-Metternich und Rhens. Bonn. Jahrbücher 1969, 169, 44–87. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, V.C. The Infrared Spectra of Minerals; Mineralogical Society: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Bortolaso, G.; Hofmeister, W.; Petrovic-Prelevic, I.; Kiewisch, B. Investigation of Quality of Commercial Mammoth Ivory by Means of X-ray Powder Diffraction (Rietveld Method) and FTIR Spectroscopy. Ivory Species Conserv. 2008, 228, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Bortolaso, G. Diagenetic Changes of Collagen in Mammoth Ivory as Revealed by Isotopic Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS) and FTIR Spectroscopy. Geobiology 2004, 53. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolf, S.; Weiss, R.-M.; Schmidt, P.; Venditti, F. On the Authenticity of Two Presumed Paleolithic Female Figurines from the Art Market. Heritage 2025, 8, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8030104

Wolf S, Weiss R-M, Schmidt P, Venditti F. On the Authenticity of Two Presumed Paleolithic Female Figurines from the Art Market. Heritage. 2025; 8(3):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8030104

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolf, Sibylle, Rainer-Maria Weiss, Patrick Schmidt, and Flavia Venditti. 2025. "On the Authenticity of Two Presumed Paleolithic Female Figurines from the Art Market" Heritage 8, no. 3: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8030104

APA StyleWolf, S., Weiss, R.-M., Schmidt, P., & Venditti, F. (2025). On the Authenticity of Two Presumed Paleolithic Female Figurines from the Art Market. Heritage, 8(3), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8030104