Abstract

While the concept of a ‘buffer zone’ is clear and well defined, the role of the buffer zone is vague, especially because a buffer zone—if any—can take on very different sizes and shapes, while their status in terms of protection and rules is very different locally. In this article, we focus on buffer zones in an urban context and explore if these buffer zones have some tourism dedication. The latter is particularly interesting since many urban World Heritage sites suffer from over-tourism. With this, we enter the field of policy, management and governance. Therefore, we analyzed three urban World Heritage sites in Belgium and commented occasionally on two more using text analysis (application and policy documents) as well as interviews (11) of interviewees that are representative of governance and expert groups. The results reveal enormous complexity because buffer zones are considered a must in the application without being well thought-out and therefore suboptimal in terms of policy and management. Streamlining the significance of buffer zones by UNESCO as well as bridging the gap between heritage conservation and tourism on a policy level can prevent the agendas of different stakeholder groups and policy fragmentation from hollowing out its potential.

1. Introduction

UNESCO World Heritage and the UNESCO list of World Heritage sites are well known, even among the general public, which is far from the case for the process to become listed and the requirements in terms of conservation management. One of the issues has to do with the management plan or management system. It might be that a management plan for the heritage site at stake is already in place or, in the other case, a management plan has to be prepared, convincing ICOMOS (not UNESCO as such) of the quality and feasibility of the plan. Elaborating such a plan or system has become very complex since, unlike as in the past, listing is not only dependent on exceptional qualities with universal value and their conservation but also by its use; these values must be communicated to the public [1]. Quite often, a management plan mentions a ‘buffer zone’ around the site, although the buffer zone is not part of the listed site as such. It is a tool to manage and protect, among other methods [2]. Because a buffer zone is not compulsory, although often created, again, a myriad of formats exist as big or small, surrounding the entire property or only part of it, a buffer zone is subject to a huge differentiation of rules in terms of do’s and don’ts and stakeholders involved. Therefore, some deeper insights into the significance of a buffer zone as a conceptual management instrument as well as its approach in practice need to be gained.

A second element in play is tourism. We mentioned already that UNESCO has become very much in favor of sharing the universal value with as many people as possible. Therefore, many World Heritage sites are promoted for tourism, taking for granted that heritage, in general, and World Heritage in particular is an excellent resource, serving tourism’s economic objectives. Because ‘World Heritage by UNESCO’ has become a quality label, many tourists have World Heritage sites on their bucket list, in so far that a number of World Heritage sites suffer from over-tourism. It is revealing that CNN Travel listed eight destinations as “the worst for overtourism” in 2023: five of them are urban World Heritage sites (Amsterdam, Athens, Barcelona, Paris, Venice) [3]; Miami is not a UNESCO World Heritage site, but the city is the gateway to the Everglades that are World Heritage while Phuket, not listed as World Heritage, is recognized as a UNESCO City of Gastronomy; Bali is the only place on their list that is less ‘urban’. Therefore, heritage management, especially in an urban context, seems of utmost importance and very urgent. This does not mean that little has been done; on the contrary, many management models and instruments have been developed and put in place [4,5,6,7], but the flow of visitors could not be stemmed, and more instruments are needed. The question that needs to be asked is if we need new instruments or if existing ones can be optimized. This is where buffer zones might enter the picture. This gave rise to the following research question: can buffer zones play a significant role in tourism development and management at urban World Heritage sites, on top of their preservation role?

Finally, we should point out why we chose Belgium as a case study. Although Belgium is a small country, it has 16 properties on the World Heritage list of which 8 are (part of) historical city centers, not even taking into account the serial nominations of urban monuments such as the Flemish Béguinages, the Belfries of Belgium, and (the north of) France. Therefore, some interesting management plans and systems are available for urban (World) heritage in Antwerp, Bruges, Brussels, Tournai, and some other cities that are on the tentative list such as Ghent. Additionally, in regard to the analysis of these management plans (documents and practices), we are able to confront the visions and policies from the communities (Dutch speaking, French speaking and German speaking) and regions (Flanders, Brussels, Wallonia), which are, independently, authorized to deal with, e.g., culture (former), environment and economy (latter). This allows us to assess some impacts of institutional fragmentation as well as complexities for matters that bridge the competences of the Regions on the one hand and the Communities on the other hand, such as heritage conservation or valorization and heritage or cultural tourism.

Therefore, we expected to learn some lessons from analyzing the World Heritage management plans of Brussels (Grand-Place), Antwerp (Plantin Moretus Museum) and Tournai (Cathedral) and their translation into practices, from exploring the role of the buffer zones and the potential of the buffer zones in coping with objectives as mentioned by the Administrator-General of Flanders Heritage Agency: “We strive for a good balance between the preservation of heritage values and other social [and economic] objectives” (LinkedIn post, 2/11/2024). Although Bruges and Ghent are not fully elaborated as cases (see Methodology), we will refer to them as well when useful.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Building a Buffer Zone

A buffer zone is defined by UNESCO as “an area surrounding the nominated property which has complementary legal and/or customary restrictions placed on its use and development in order to give an added layer of protection to the property” [2]. Buffer zones do not possess any Outstanding Universal Values themselves, but they protect the World Heritage sites against any negative impacts [8] and cannot be modified without the approval of UNESCO [9]. Therefore, a buffer zone provides a bigger context to the protected World Heritage site and includes the surrounding landscape into its governance. Nevertheless, its role and functioning is complex and confusing due to a lack of regulation and protection measures that are applied to the buffer zones as standard [10].

The concept of a buffer zone was introduced at the end of the 1970s, in order to protect natural heritage and archeological sites [11]. In the 1980s, all natural and cultural heritage properties were encouraged to include buffer zones into their nomination file until, in 2005, a buffer zone was made mandatory [12,13]. In the current nomination process, both the inclusion of a buffer zone as well as its omission are possible but should be justified [14]. The inclusion of a buffer zone and its capacity depend entirely on the World Heritage site to be protected. It can be intended to counter perceived threats from outside its borders or respond to local legislation at the site or a broader context [9]. It is of utmost importance that a buffer zone is created in a thoughtful way because, normally, it has an impact on all stakeholders operating in the buffer zone. For instance, particular types of real estate development can be limited in the buffer zone, which has an impact on local politics as well as on the inhabitants, owners of buildings and economic activities in this buffer zone [15]. In practice, especially in the earlier years, buffer zones were created quite arbitrarily, becoming empty shells instead of useful tools [16]. On the other hand, a buffer zone as it is conceptualized for the nomination file should include all stakeholders and facilitate a sustainable use of the World Heritage property. This means that the local community should also be taken into consideration, especially their involvement in the valorization of the World Heritage property and its buffer zone. For example, this can be carried out through tourism-supporting activities such as accommodation and food outlets [9].

2.2. Tourism and UNESCO

Culture has been one of the main drivers to travel since the beginning of the tourism industry, with cultural tourism accounting for more than 39% of all international arrivals [17]. Cultural (heritage) tourism has become mainstream, while it used to be a niche in the past [18]. Cultural tourists are looking for new information and experiences, both in a tangible and intangible way. An important aspect in this search for new information is authenticity [19], which is underlined by UNESCO as well [2]. The effects of tourism are twofold. On the one hand, tourism can be very beneficial in protecting heritage because of the broad support for conservation of the properties visited. On the other hand, the same properties can deteriorate because of increased interest (numbers) and careless or inappropriate use (wear and damage) [20,21]. In other words, UNESCO works towards a preservation of sites for future generations, but, at the same time, by putting their label on a site, it attracts tourists who jeopardize the site, consciously or unconsciously [22]. Because of its status, World Heritage can also be a stimulus for cultural tourists to spend more money and to stay longer in the region, while they are often more involved in sustainability than the average tourist [23]. Therefore, impacts are profound and positive up to the point where this tourism turns into over-tourism.

The first Operational Guidelines, which were drawn up in 1972, reflected suspicion towards tourism as a potential threat to World Heritage. It took until 2017 to see this removed from the Operational Guidelines. Human-made factors were still left in these guidelines as factors that could endanger World Heritage sites [24]. But the danger to heritage goes further than only physical danger. The commodification of heritage can also endanger the site by reducing it to a tourism product. This leads to a diminishing authenticity and even to the site becoming performative [17]. This led to the founding of the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Program in 2001 [25]. This program showcased very clearly the shift from ‘tourism as a threat’ to ‘tourism as a driver for heritage’ [26]. It introduces stakeholder management as a central idea in tourism and heritage management [25]. This program describes tourism as critical for World Heritage and not only in a negative way. There should be cooperation between World Heritage sites and the tourism sector in order to present the OUVs in an effective and authentic way. Nevertheless, the program focuses especially on capacity building and local context needs, as well as policy and frameworks, rather than special zoning issues.

Stakeholder involvement is something that has been heavily debated within UNESCO circles. The Operational Guidelines of 1988 even explicitly stated that the nomination proposal should be secret from the public in order to keep the process as objective as possible [27]. Traditionally, the management of World Heritage sites has been approached top-down, with the decision-making power in the hands of professionals, but, in order to create an efficient management system, more stakeholders must be involved in its creation [28,29]. This positive development in moving towards a more participative approach opens up possibilities for actors in the buffer zones to get involved as well, but this is very much dependent on insights of the proposal designers.

As for the 2024 version of the Operational Guidelines (WHC.24/01) [30], it is clear that the (potential) role of a buffer zone should be taken very seriously in new applications towards a potential nomination to the World Heritage List. The document mentions that “Details on the size, characteristics and authorized uses of a buffer zone […] should be provided in the nomination” (article 104), while “An integrated approach to planning and management is essential to guide the evolution of properties over time and to ensure maintenance of all aspects of their Outstanding Universal Value. This approach goes beyond the property to include any buffer zone(s), as well as the wider setting. The wider setting may relate to the property’s topography, natural and built environment, and other elements such as infrastructure, land use patterns, spatial organization, and visual relationships. It may also include related social and cultural practices, economic processes and other intangible dimensions of heritage […]” (article 112). Although tourism is implicitly present in terms such as ‘uses’, ‘infrastructure’, ‘land use patterns’ and ‘economic processes’, it is a pity that ‘tourism’ is not explicitly mentioned since the need for professional insights in tourism development and visitors management is often underestimated. Moreover, this has no relevance for the older World Heritage sites.

3. Methodology

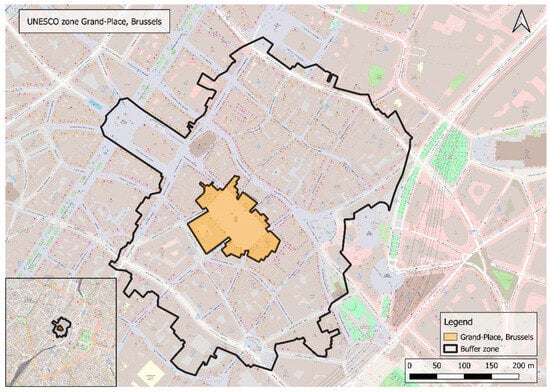

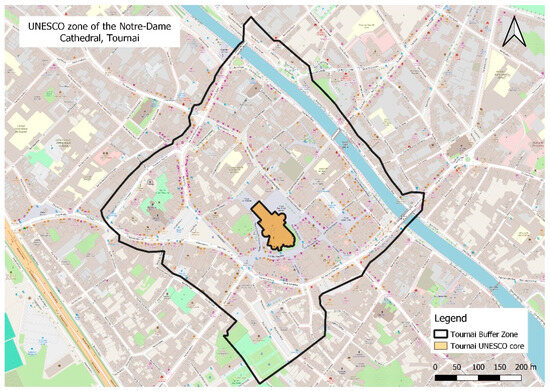

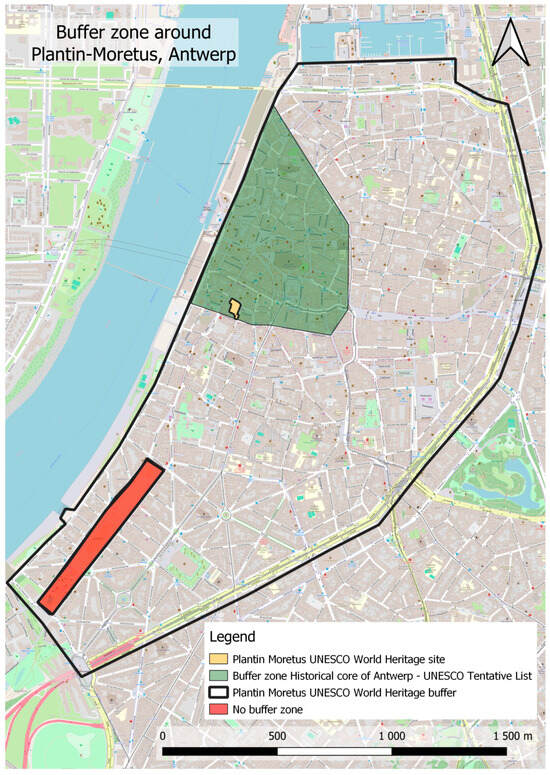

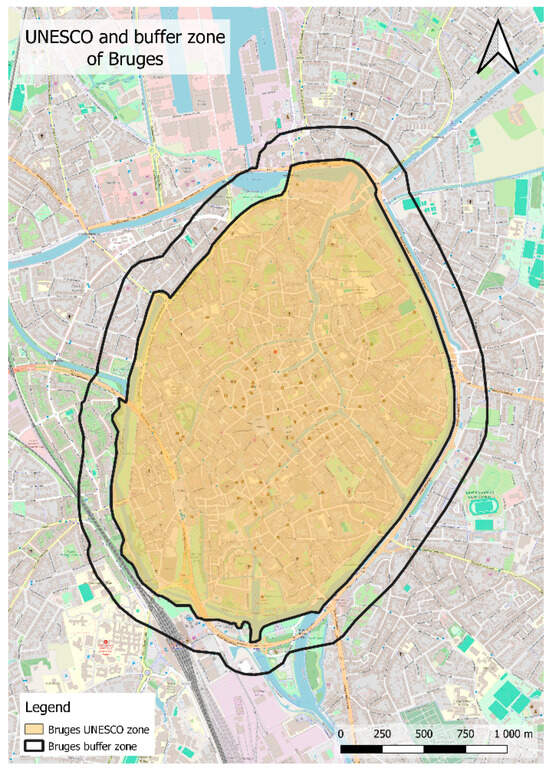

We chose to conduct our research in a qualitative manner, based on text analysis and semi-structured interviews with relevant key persons in the governance and experts stakeholder groups 1. As mentioned in the Introduction, we focused on three Belgian cultural UNESCO World Heritage sites, namely, the Grand-Place in Brussels (Figure 1), the Notre Dame Cathedral in Tournai (Wallonia) (Figure 2), and the Plantin Moretus Museum in Antwerp (Flanders) (Figure 3). Originally, the historical centers of Bruges (Figure 4) and Ghent were on our cases list as well. Of all Belgian World Heritage sites, Bruges is the one most threatened by over-tourism; nevertheless, we did not study this case because the buffer zone, although present, is too narrow to constitute a potential spill-over zone for tourism. As for Ghent, which is on the tentative list, we were told that the proposal is unavailable to the public (and even to researchers), which is not unusual (see previous section). Nevertheless, we referred to Bruges and Ghent when useful.

Figure 1.

The Grand-Place UNESCO zone in Brussels and its buffer zone (author’s design).

Figure 2.

The Notre Dame Cathedral UNESCO zone in Tournai and its buffer zone (author’s design).

Figure 3.

The Plantin Moretus Museum UNESCO zone in Antwerp and its buffer zone (author’s design).

Figure 4.

The Bruges UNESCO zone and its buffer zone (author’s design).

All sites have a buffer zone surrounding the listed property (buildings or zone), presenting opportunities and challenges for tourism.

As for the text analysis, multiple documents made public through UNESCO or governmental organizations provide details on the buffer zones in our cases such as the following:

- The nomination file of the Grand-Place in Brussels [31].

- The nomination file of the Tournai Cathedral [32].

- The nomination file of the Plantin Moretus Museum in Antwerp [33].

- The management plan for the Grand-Place in Brussels [34].

- The management plan for the Plantin Moretus Museum in Antwerp [35].

We also contacted multiple stakeholders who are involved in World Heritage in Belgium, especially focused on the 3 sites we researched, in order to conduct interviews. The biggest challenge was a non-response or negative response from potential interviewees. In total, 33 stakeholders were contacted for this research. Of those, only 11 stakeholders agreed to be interviewed. This high non-response seems to reflect an unfamiliarity with the subject, even among professionals, and (or) a certain unexpected sensitivity that surrounds the subject. In total, the communication, be it an interview, phone call(s), or email communication(s), of 15 stakeholders was used. The low response may be of some concern as the ones participating may be more motivated and have stronger opinions. The high non-response seems to be rather linked with ignorance about the subject (from the replies of people who chose not to collaborate). During the interviews, the interviewer took care to ask opinions on opposite points of view while taking into account that the interviewees are professionals considered key persons who have a certain knowledge of the subject. In line with this, we believe that semi-structured interviews were the right method. Semi-structured interviews allow for some flexibility, while the researcher was attentive to inconsistencies. In our case, all interviewees were contacted with more or less the same interview protocol, respecting the ‘structure’ while focusing most on the aspects in line with their competences (refer Appendix A).

For all contact, we used the native language of the (potential) interviewees, who were French or Dutch speaking, except for one particular case. Therefore, all stakeholders could express themselves in their own native tongue while the interviewers, as the authors, master three languages (Dutch, French, English). We interviewed one native Portuguese speaker in English since this person uses English on the job. Therefore, no interpreter was involved while the interviewers studied the specific terminology in each of the three languages as part of the preparation for the interview.

All interviews were recorded with the informed consent of the interviewees. Afterwards, the interviews were transcribed and coded using NVivo for the following reasons: first, deductively, in order to obtain an overview of the themes based on the literature and basis of the interview protocol and, secondly, more inductively, in order not to miss any new important topic put forward by the interviewees. The five large themes within the interview protocol and deductive coding were as follows: professional connections with (UNESCO World) heritage, UNESCO listing and tourism, the significance of buffer zones and their potential value for tourism, stakeholder involvement and, finally, the translation of concepts and principles in (good) practice. Elements such as ownership and collaboration enriched the coding in an inductive way.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Unique Characteristics of UNESCO in Belgium

Belgium is recognized as a state party by UNESCO, but it hosts two distinct commissions. There is the Flemish Commission for UNESCO and the Belgian Francophone and German-speaking Commission for UNESCO, which is in line with the federal state structure presented in the Introduction. To complicate matters, the Belgian branch of ICOMOS only exists in name and is actually composed of two different branches: ICOMOS Vlaanderen-Brussel (for Flanders and certain items in Brussels) and ICOMOS Wallonie-Bruxelles (for Wallonia and certain other items in Brussels). These branches have their own set of rules and regulations. For instance, the level of protection of buffer zones in Flanders and Wallonia is different. In Flanders, this protection consists of a suggestion or advice, while, in Wallonia, the protection is much harder to ignore. The Walloon government turned (part of) the buffer zone into a protection zone in order to legally solidify its protection. As a result, there is no fully fleshed out, single commission that is focusing on UNESCO matters only and throughout the entire country, while, accordingly, the budgets are fragmented. As mentioned by our interviewee from the Flemish UNESCO Commission, this budget needs to stretch to all aspects of UNESCO, not only World Heritage. Although the Belgian federal structure with independent competences for regions and communities is quite unique, it is comparable to a situation with cross-border (serial) nominations and with a common fragmentation between different policy departments, with culture and heritage on the one hand and economic matters (including tourism) on the other hand. The fact that, in Belgium, cultural (immaterial) heritage and material heritage belong to different policy layers shows that an integrated policy and budgeting can be extremely difficult.

“[Concerning the split of funds between the different communities,] it is really complicated. I think it’s the [political] concept. It is larger than heritage alone” (City of Brussels, Appendix A)

4.2. Understanding the UNESCO Buffer Zones in Belgium

State parties create the Operational Guidelines that they themselves have to follow. As for the buffer zones, the guidelines hold (held) few rigorous rules and regulations. An example of this is the buffer zone surrounding the historic center of Bruges. This buffer zone is a 200 m offset of the borders of the World Heritage property, not taking into account any street pattern except for being parallel to the medieval walls. At the time of the nomination, this buffer zone was deemed adequate by experts. However, with changing views on heritage and heritage protection, this buffer zone does not hold up anymore according to some interviewed experts (Flemish Heritage Agency, Appendix A). An opposite example can be found in the buffer zone surrounding the Plantin Moretus Museum in Antwerp. In fact, one can distinguish two buffer zones, which are concentrical circles. The largest buffer zone encompasses 311 hectares, which is far too large to be a logical buffer zone surrounding a single building, which is the Plantin Moretus Museum. The creation of this buffer zone was not intended to serve a dynamic management policy but, rather, it ‘frames’ the ‘Officinia Plantiniana’ where the Plantijn family started its printing empire in the sixteenth century as a scene. In such cases, buffer zones are seen rather as a burden than a useful tool. A smaller buffer zone corresponds to the historical core of Antwerp, which is also on the UNESCO Tentative List. This zone has been developed more recently and has a logic and strategy behind it, and, therefore, the Plantin Moretus Museum wants to switch to the smaller buffer zone (Plantin Moretus Museum, Appendix A). The idea that a buffer zone could and sometimes should be adapted is not always welcomed in the UNESCO Headquarters, as was the case for Plantin Moretus. This also gives the protection of heritage a political dimension (Flemish Heritage Agency, Appendix A). This is also why the Flemish Béguinages (serial listing) do not possess buffer zones up to this day.

“Ten years ago, we tired, specifically for the Plantin Moretus Museum [to reduce the buffer zone], because we saw a problem with it and wanted to see if we could fix it. […] We created an alternative buffer zone that was much smaller, but had a better story. We went to ICOMOS with it. […] They said bluntly: ‘Keep the bigger buffer zone, because a bigger one is better.” (Flemish Heritage Agency).

This sometimes restrictive nature of a buffer zone can lead to buffer zones being shrouded in mystery, as is the case in Ghent. On the one hand, the delimitation of the buffer zone and the arguments behind it are not clear, while (some) building permits for the restauration of buildings in the city center refer, among other issues, to the UNESCO buffer zone 2. When the responsible city services were contacted, they denied the fact that there is some form of policy based on these buffer zones. In turn, the Belfry (serial nomination) has no buffer zone, although it is located in the middle of the historical core.

These examples show that buffer zones might be an easy concept, but they are not easy to implement and manage because, as in the Flemish cases, World Heritage sites (buildings and building complexes) might overlap with other World Heritage properties (such as an entire historical city core), which makes a coherent policy very complicated. Nevertheless, complexities should not prevent a good policy framework. In Bruges, one has a commission tasked with managing the World Heritage site, also considering the buffer zone (Flemish Heritage Agency, Appendix A). The gigantic buffer zone surrounding the Plantin Moretus Museum in Antwerp, on the other hand, is given little attention, and, therefore, no particular policy concerning the buffer zones is put in place (Plantin Moretus Museum, Appendix A). This can be explained by the unmanageable surface of the buffer zone (as mentioned above) but eventually also by the fact that the tourism office (tourism policy) does not focus on the World Heritage in the city because of abundant other assets and activities.

4.3. Tourism and UNESCO World Heritage in Belgium

Including tourism into the UNESCO World Heritage management plans is something that has been on the rise in recent years [1]. As mentioned before, in the past, tourism was referred to mostly because one was concerned about sustainability and overtourism. The reason(s) why a site wants to become recognized as a World Heritage site can shift or broaden. In principle, conservation for present and future generations is the prime goal, but, recently, the increase in tourism might be an additional objective. Accordingly, promotion and image building can foster the growth of tourism after inclusion onto the list (Flemish Heritage Agency, Appendix A). However, sometimes, the agencies responsible for heritage are not concerned with tourism at all, due to policy fragmentation and lack of expertise in the field. Therefore, it is interesting to notice that, recently, the Administrator General for both Visit Flanders and the Flanders Heritage Agency has become one and the same person.

“It [tourism] is not something that sits high on our agenda. […] We do not have expertise in tourism and often avoid the discussion.” (Flemish Heritage Agency, Appendix A).

On the other hand, some sites have taken measures to regulate tourism and even implemented a cap in the amount of visitors per day in order to safeguard the heritage. Of course, this depends on the type of World Heritage site or property; measures are a lot easier to implement for a well-defined, closed or closable building complex such as, e.g., the Acropolis in Athens rather than an open system, such as a historical city where people can move in and out freely. As mentioned before, apart from Bruges and Brussels, not many cultural heritage sites in Belgium suffer from over-tourism. This can be seen when comparing the tourism numbers for several Belgian and international cities (Appendix B). Bruges and the city of Brussels have the highest pressure from tourism, when comparing overnight stays with the number of inhabitants: 18 and 24. overnight stays per inhabitant, respectively. This is very comparable to figures for well-known (over-)touristic hotspots like Amsterdam and Barcelona with 24 and 21.4 overnight stays per inhabitant. However, these numbers pale in comparison with Venice, which has 50 overnight stays per inhabitant. Brussels, of course, is home for many international institutions and headquarters, which implies many overnight stays that are not related to (heritage) tourism. Further, overnight stays are not always a good indicator since they overlook day tourism, which is difficult to measure. Statistics from Visit Bruges reveal a figure of 8.3 million visitors with 6.1 million day tourists (2023) [36]. This implies a ratio of almost 70 visitors per inhabitant, and even this figure fails to take into account that the visitors are not equally spread across the territory of the municipality, which is much larger than the historical city. On average, the Art Cities in the region of Flanders feel a higher pressure compared to cities in the region of Wallonia, where only Mons and Dinant have more than two overnight stays per inhabitant. Therefore, Flanders actively monitors the satisfaction of the inhabitants of the Art Cities with tourism [37], but the management of (the risk of) over-tourism is left to the individual cities. Therefore, and because of the abundance of (World) heritage sites in Flanders, especially in the many medieval cities, some tourism offices even choose not to focus on World Heritage, in order to stand out from competing cities. As mentioned before, this is the case with Antwerp, which focuses on Rubens, diamonds, and fashion in order to create a unique product that can compete with Bruges, which is much more known as a UNESCO World Heritage site (Plantin Moretus Museum, Appendix A). On top of the ‘Grand-Place’, Brussels has an abundant set of Art Nouveau buildings, some of which were designed by the architect Victor Horta, that are listed, but Brussels has more to offer, such as the comics culture or the European quarter with the EU-buildings, which may be more interesting to focus on in the promoted image of the city. Therefore, the tourism scene is dominated by heritage but not particularly by UNESCO World Heritage. Especially, the Brussels’ agencies responsible for tourism and heritage operate separately because Brussels suffers most from the division of competences between regions and communities 3 that restricts co-creation opportunities [31].

Therefore, the focus away from World Heritage as a tourist hotspot is something that is sometimes welcomed by the management of these sites. The Plantin Moretus Museum, for example, wants to be seen as a ‘house’. In 2023, they almost reached their maximum visitors’ number, and the management does not want to go beyond the threshold of sustainability. Therefore, they do not want to market towards new potential visitors, knowing that their carrying capacity has been reached. The Museum tries to use the buffer zone in order to take some pressure away from the house. They do this by allowing people to freely exit the house and come back once they have paid the ticket in order to have a drink or eat something on the neighboring squares (Plantin Moretus Museum, Appendix A).

“We need to look proactively to the future, we need to find solutions for these problems [an increase in pressure to the site due to schools visiting] that will become bigger over the next ten years. ” (Plantin Moretus Museum, Appendix A).

Unlike Antwerp, the city council in Tournai does not fear an immense increase in visitors when using the UNESCO label to market their property. On the contrary, they want to increase the amount of visitors. At the moment, they are struggling with the supply chain of tourism in order to retain these visitors. The accommodation infrastructure in the city center is too weak in order to develop an extensive tourism plan. Their current goal is to develop a sustainable tourism system in order to increase the amount of tourists that visit the city and its UNESCO World Heritage site. Promoting the Cathedral, which is a World Heritage site and the buffer zone surrounding the Cathedral, must strengthen the ‘tourism product’, making its reach broader and therefore more attractive to visitors (Tournai 1, Appendix A).

4.4. Tourism and the Buffer Zones in Belgium

Stakeholders agree that it is justified to be concerned about the combination heritage conservation–tourism development. These two goals are not necessarily complementary, and, in order to encapsulate both into the same tool (e.g., buffer zones), they believe the tool will (need to) be weakened from the conservation side. Nevertheless, some interviewees are convinced that it is possible to create an efficient tool for visitor management, which can be a new kind of buffer zone adapted to the tourism function. The vision behind it is interesting:

It is a way of drawing third parties’ attention to the fact that “being a World Heritage Site does not merely stop with your World Heritage site, but is also and perhaps even especially about what happens around it. [The WH site is] the goose with the golden eggs, so you’re going to take good care of that. But you are also going to control your urbanization. That is exactly what the buffer zone is about. [… But] I also have some sympathy for the other side, that other perspective on a buffer zone: the extra story you can tell or an additional framing of the place or enriching with elements that are supportive without being the essence. [From this perspective] I find it strange to label these zones a ‘buffer zone’, because there the infill is not buffering at all, but rather supporting or complementary or whatever. (Flemish Heritage Agency, Appendix A).

Tourism in the buffer zone is not artificial. When World Heritage sites are visited by tourists, the areas surrounding this World Heritage site already are a kind of spill-over zone for tourists. With interjection from the government, some of these areas can become fully catered towards tourists, something that authorities should make conscious decisions about. In Brussels, for example, the site management includes the buffer zone into a visitor management system. They make conscious decisions to diversify the economic supply in this buffer zone in order to make sure it does not become a tourist wasteland riddled with chocolate and waffle shops. They work together with owners of empty commercial properties to organize pop-up stores that can offer a qualitative proposition and to restore the historical storefront, which has often been ‘renewed’ by enlarging windows and using low-quality materials and design in the past. The scene should be joyful for tourists as well as residents (site manager of the Grand-Place in Brussels, Appendix A). Now that the area surrounding the Grand-Place (the so called ‘Îlot sacré’) has become heavily touristified, one realizes that reversing this process is more difficult than preventing it through a management plan that fully respects the role and function of a buffer zone. This is why, according to the site manager of the Grand-Place in Brussels, the Brussels’ de-touristification of the environment of the Grand-Place is very slow.

“We would like to create a more balanced type of retail in the centre. We have the Rue au Beurre, that is one of the streets that ends at the Bourse. Only chocolate shops. We had a supermarket there at a certain moment, but now they left, and it is chocolate again. […] It goes very slowly, but we see some quality shops coming into the street” (City of Brussels).

4.5. Collaboration, Management, Ownership and Responsibility

The structure of management plans is well defined by the UNESCO Guidelines, but the exact content of a management plan is up to the state party itself. In Belgium, this means that there is a difference between Flanders and Wallonia, although, in general, all Belgian World Heritage management plans are extremely well elaborated and more in-depth than the management plans for non-UNESCO listed monuments. In the case of the Plantin Moretus Museum, the management plan covers 440 pages, and its outline follows the UNESCO guidelines in detail. On top of this, the management plans include specific visions for the future with concrete goals. Decisions were formulated and justified. In these documents, there is always some attention to tourism, although some criticisms could be heard among the interviewees [35].

Some thinking has been done within the Convention in the last few years especially about sustainable tourism, overtourism, other ways of doing tourism, or marketing something touristically. And I think there is a strategy around sustainable tourism, for which there exists a cooperation with UNWTO. [But …]. We do not have tourism objectives. We are not involved in that. We have no expertise in the subject and we often let that discussion run its course. We haven’t received an explicit request from our colleagues [from tourism]. (Flemish Heritage Agency, Appendix A).

All interviewees agree on a shift from top-down to more bottom-up management. It is happening, but one carries a legacy from the past, which implies that some World Heritage sites in Flanders (Belgium) lack a feeling of ownership and therefore taking responsibility among relevant stakeholders (Flemish Heritage Agency, Appendix A). Nevertheless, this cannot be generalized. Bruges, for example, holds an emblematic role in this feeling of ownership. It was the residents of the city that notified UNESCO when there were construction plans that could intervene with the World Heritage site (historical city core). The reaction of the city council was to create a local World Heritage Committee and an intensive (new) management plan. Not only were the disagreements settled, but it reinforced a feeling of local pride in the city. They also included the local population when reevaluating parts of the city, such as its Béguinage (Flemish Heritage Agency, Appendix A).

“In Bruges they wanted to focus on the immaterial aspect as well. This aspect is included in a different Convention, linked to living communities. […] We tried to bring these two Conventions together […]. The Béguinage is a quiet place in the middle of a busy touristic city [and you want to keep it like this] How do you go about this problem?” (Karvansera, Appendix A)

On the other hand, in Ghent, there are major problems finding the right point of contact to gauge opinions towards the ‘major’ heritage that one has in the city. Further, Ghent is much more flexible with allowing modern interventions in the historical city, which leads tourism agencies to describe the city as a “wonderful mix of a living city and a vibrant past” [38]. The sense of ownership is different because cities such as Brussels, Antwerp and Ghent are major cities with a (historically) very diversified and strong economic basis and intensive population dynamics. Without generalizing, one can state that some groups among the local population even do not identify with heritage [39], while, in smaller cities and certainly in Bruges, the local residents are very much aware of their material heritage as a resource, and they are proud to show this to visitors [40].

Tournai, in turn, is very much aware of its limited capacity and, therefore, has an interesting approach to foster tourism development at their UNESCO World Heritage site in which the buffer zone plays a prominent role. They put a system in place that involves stakeholders who operate in the buffer zone of the Cathedral to give their input and opinions on the management of the site. Tournai’s philosophy is that creating an integrated tourism ecosystem in the buffer zone will also lead to a supported management plan of the World Heritage Site itself (Tournai 1, Tournai 2, Appendix A). Nevertheless, the emphasis is on the economic parties, which can raise issues on sustainability and support in the long term.

“We try to host more tourists. To do that we need accommodation. We have restaurants, but accommodations and hotels is something we are lacking. […] We also need more publicity about everything that we possess [as a city]. [For example] we have a lot of visitors from northern France who presently only come to drink something, or eat in a restaurant.” (Tournai 2, Appendix A); “We do our best [to include stakeholders] in Tournai. We let people meet and network.” (Tournai 1, Appendix A).

5. Conclusions

When starting this research, we assumed that the buffer zone, as a concept, is clear and that, if present, authorities and experts could be interested in its potential role beyond the conservation of a World Heritage site. During the fieldwork, interviews with key persons made clear that some buffer zones are not well established and, as such, seem to be a burden rather than a helpful instrument, even when only considering their conservation role. Although the Operational Guidelines of 2024 are quite clear about the role and the format of buffer zones, it leaves a lot of room for interpretation and superficial operationalization; this was even more outspoken with earlier versions of the Operational Guidelines and with properties listed in a less recent past. The fact that the delimitation of the buffer zone makes it often an impractical and even disturbing entity results in being ignored. The usefulness of buffer zones, especially with older World Heritage properties, can be questioned, and, therefore, some flexibility in redefining buffer zones, in shape and surface, can be beneficial in view of their primary role, which is supporting the conservation of the site but also, and increasingly, fostering other uses and functions.

Therefore, although buffer zones are present in each of the studied cases, at first sight, they contribute little to a practical integration of preservation and tourism use. We have to admit that, when analyzing the (well-elaborated) application files and the management plans, a fundamental reflection on the role of the buffer zone was lacking. As mentioned, in the case of Bruges, the buffer zone is too narrow to be useful, and, in the case of Antwerp, the buffer zone is too large to be manageable. We saw a temptation to delimit the historical core of the city as a buffer zone, which is very much welcomed by UNESCO but at least very unpractical for hands-on management. Therefore, cities such as Tournai, with a defined manageable buffer zone as well as a comparable protection zone, are supported by regional legislation.

The structuring of competences among policy agencies makes it even more complex if one is thinking about an integration of preservation and tourism management within the buffer zone. Of course, the federal policy structure is interesting in many ways, but the division of policy competences between personal matters (culture) and territory-linked matters (e.g., economy) is not advantageous for solutions that are bridging both, such as cultural heritage and heritage tourism. Nevertheless, the fragmentation of policy competences is not exceptional and occurs in many regions and countries. The fact that heritage is often integrated with culture and tourism with economy hinders an integrated approach and collaboration between experts on heritage on the one hand and professionals in tourism on the other hand. Heritage experts acknowledge that their expertise in tourism is small, and, therefore, they do not have tourism on their agendas. This does not mean that tourism is never taken into account. It simply depends on the aims of the site developers. In some cases, one wants to foster tourism (e.g., in Tournai) since the site suffers from under- rather than over-tourism, while, in other cases, one wants to avoid the attraction of more tourists because the site should avoid over-tourism at all costs. An example of this last type is the Plantin Moretus site in Antwerp, where site managers are very mindful of the carrying capacity of the site and are very attentive not to exceed it.

Even when the buffer zone can play a role within tourism development, as a tourism buffer zone, the question remains on what to focus: restrictive building policies or public space management, including parking spaces, public transport, souvenir shops, interactions with locals, etc. The complexity here lies in the different stakeholders who have different wishes on how to manage the public space and what rules (restrictions) to impose on a local level. One can assume that this is the case with many World Heritage sites that have been listed a long time ago and therefore have quite dated management plans and practices. A significant evolution took place in the way stakeholders look at protective tools, such as the buffer zone. This not only leads to a lack of systematization in the protection of World Heritage sites as such but also to an inability to let multidisciplinary teams take responsibility, which can be seen in Brussels. Visit Brussels said not to have anything to do with the management of the buffer zone, while the site manager has little cooperation while trying to handle the touristification of the site.

Another question remains whether a buffer zone, as a tool for preservation, must itself be protected. In other words, is it part of the story or even able to create an extra story and therefore fuel the value of the World Heritage site? Therefore, Tournai is an interesting case showing that the buffer zone becomes an interesting tool if a buffer zone is duplicated by a protection zone that has virtually the same goal. The buffer zone is needed for UNESCO, and the protection zone is needed to enforce it legally on a local and regional basis. On top of this, the Tournai Cathedral, as a World Heritage site, is not able to attract many visitors on its own. This might not be an explicit aim in the management plan, but a marketing effect of the World Heritage label is welcome. Linking the buffer zone with the site through a story that contributes to the experience of the visitors while providing accommodation and infrastructure shows that the role of a buffer zone can go beyond conservation.

Finally, “to measure is to know”. It is true that we do not have enough (detailed) data (e.g., on visitors in the buffer zones), while other data such as detailed land use or the historical value of buildings are spread among different stakeholders and institutions. Two important stakeholder groups were not taken into account in this research: the residents and the tourists. This does not mean that these groups do not have a role to play. On the contrary, tourists are able to explain which elements contribute to a good experience and which are the disturbing factors, while residents have a good view on and feel for carrying capacity. Unfortunately, this kind of information can only be gathered by regular surveys, which might go beyond the ambitions and possibilities of a heritage site, even when it concerns World Heritage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.V. and D.V.; Methodology, N.V. and D.V.; Transcripts, coding and Formal analysis, N.V.; Investigation/interviews, N.V.; Writing—original draft preparation, N.V.; Writing—review and editing, D.V.; Visualization, N.V.; Supervision, D.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Transcripts of the interviews are available in the original language (Dutch or French) with the authors and can be consulted at any time.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. List of Interviewees

| Organization | Position | Language | Date | Medium | Length |

| Herita | Stakeholder manager | Dutch | 26/04/2024 | In person | 21:50 |

| City of Tournai (1) | Alderwoman of tourism | French | 07/05/2024 | Teams | 25:00 |

| Flemish Heritage Agency | Policy officer | Dutch | 07/05/2024 | Teams | 45:05 |

| Monumentenwacht | Team responsible for Antwerp | Dutch | 08/05/2024 | Phone call | 13:47 |

| Steenmeijer Architecten | Architect | Dutch | 15/05/2024 | Teams | 24:16 |

| Karvansera | President | Dutch | 17/05/2024 | Teams | 01:03:23 |

| Plantin Moretus Museum | President | Dutch | 24/05/2024 | Teams | 58:28 |

| ARAU | President | French | 29/05/2024 | Teams | 40:49 |

| Flemish UNESCO Commission | Former president | Dutch | 04/06/2024 | Teams | 53:25 |

| City of Tournai (2) | Alderman of urban planning | French | 07/06/2024 | Teams | 20:18 |

| City of Brussels | Site Manager of the Grand-Place | English | 07/06/2024 | Teams | 48:33 |

| City of Ghent | President of city archeology | Dutch | 03/05/2024 | / | |

| City of Antwerp | Spokesperson to the alderman of tourism | Dutch | 24/04/2024 | / | |

| Visit Brussels | Responsible for heritage | French | 08/05/2024 | / | |

| City of Ghent | Information point city archeology | Dutch | 07/04/2024 | Phone | 01:18 |

Appendix B. List of Overnight Stays (Per Inhabitant) for Cultural Cities

| City | Overnight Stays | Inhabitants | Overnight Stays Per Inhabitant |

| Belgium | |||

| Antwerp | 2,538,995 (2023) [41] | 536,079 (2023) [42] | 4.71 |

| Bruges | 2,152,881 (2023) [41] | 119,445 (2023) [42] | 18.02 |

| Ghent | 1,606,631 (2023) [41] | 268,122 (2023) [42] | 5.99 |

| Leuven | 558,993 (2023) [41] | 102,851 (2023) [42] | 5.43 |

| Mechelen | 271,903 (2023) [41] | 88,463 (2023) [42] | 3.07 |

| Brussels (Cap. Reg) | 9,389,831 (2023) [43] | 1,235,192 (2023) [42] | 7.60 |

| Brussels (city) | 4,788,814 (2023) [43] | 192,950 (2023) [42] | 24.82 |

| Namur | 184,584 (2018) [44] | 110,939 (2018) [45] | 1.66 |

| Liège | 359,597 (2018) [44] | 197,355 (2018) [45] | 1.82 |

| Mons | 195,454 (2018) [44] | 95,299 (2018) [45] | 2.05 |

| Tournai | 77,192 (2018) [44] | 69,554 (2018) [45] | 1.11 |

| Dinant | 132,616 (2018) [44] | 13,544 (2018) [45] | 9.79 |

| Abroad | |||

| Amsterdam | 22,100,000 (2023) [46] | 918,194 (2023) [47] | 24.07 |

| Barcelona | 36,404,956 (2023) [48] | 1,1702,814 (2023) [49] | 21.38 |

| Venice | 12,628,000 (2023) [50] | 252,340 (2023) [51] | 50.04 |

Notes

| 1 | Due to the complexity of the creation and implementation of buffer zones surrounding UNESCO World Heritage sites, residents and tourists were not included in this research since they are non-experts and barely included in the institutional policy or management layers. |

| 2 | We found an example of such a building permit, delivered by the Department of Urban Planning, City of Ghent, 2021 [32]. |

| 3 | There is a Brussels Capital Region, but there is no Brussels Community as a policy layer. |

References

- Vanneste, D. Site Management Systems (Theme 2). In Tourism Management at UNESCO World Heritage Sites. MOOC, FUN Platform. 2021. Volume 3. Available online: https://www.fun-mooc.fr/ (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- UNESCO. World Heritage Centre Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelor, B. These Were 2023’s Worst Destinations for Overtourism. Here’s How to Avoid the Crowds. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/travel/2023-worst-destinations-overtourism-avoid-crowds/index.html (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Camatti, N.; Bertocchi, D.; Carić, H.; Van Der Borg, J. A Digital Response System to Mitigate Overtourism. The Case of Dubrovnik. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Borg, J. The Role of the Impacts of Tourism on Destinations in Determining the Tourism-Carrying Capacity: Evidence from Venice, Italy. In Handbook of Tourism Impacts. Social and Environmental Perspectives; Stoffelen, A., Ioannides, D., Eds.; Edward Elegar: Glos, UK, 2022; pp. 103–116. ISBN 978-1-80037-767-7. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Russo, A.P. Anti-tourism activism and the inconvenient truths about mass tourism, touristification and overtourism. Tour. Geogr. 2024, 26, 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibrijns, G.S.; Vanneste, D. Managing Overtourism in Collaboration: The Case of “From Capital City to Court City”, a Tourism Redistribution Policy Project between Amsterdam and The Hague. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, O. World Heritage and Buffer Zones; Piatti, G., Ed.; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, D.; Badman, T.; Bomhard, B.; Rosabal, P.; Dingwall, P.; Marshall, D.; Denyer, S. Preparing World Heritage Nominations; World Heritage Resource Manual; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Darabi, H.; Behbahani, H.I.; Shokoohi, S.; Shokoohi, S. Perceptual Buffer Zone: A Potential of Going beyond the Definition of Broader Preservation Areas. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. World Heritage Centre Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the Convention (1); UNESCO: Paris, France, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Schlee, M.B. The Role of Buffer Zones in Rio de Janeiro Urban Landscape Protection. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2005 OPGU Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. World Heritage Centre Basis Texts of the World Heritage Convention (1972); UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sakellariadi, A. Strategic Participatory Planning in Archaeological Management in Greece: The Philippi Management Plan for Nomination to UNESCO’s World Heritage List. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2013, 15, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiong, K.; Liu, Z.; He, L. Research Progress on World Natural Heritage Conservation: Its Buffer Zones and the Implications. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, D.H. Culture as an Instrument of Local Development. In Managing Natural and Cultural Heritage for a Durable Tourism; Trono, A., Castronuovo, V., Kosmas, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 45–56. ISBN 978-3-031-52041-9. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, M. Niche Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-08-049292-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ababneh, M.A.; Masadeh, M. Creative Cultural Tourism as a New Model for Cultural Tourism. J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2019, 6, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakey, N.M. Studying World Heritage Visitors: The Case of the Remote Riversleigh Fossil Site. Visit. Stud. 2012, 15, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Cros, H.D. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership Between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7890-1105-3. [Google Scholar]

- González Santa-Cruz, F.; López-Guzmán, T. Culture, Tourism and World Heritage Sites. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Kingdom National Commission for UNESCO. World Heritage Status: Is There Opportunity for Economic Gain? Lake District World Heritage Project—IC invest in Cumbria—Northwest Regional Development Agency. Available online: https://unesco.org.uk/resources/world-heritage-status-is-there-an-opportunity-for-economic-gain (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Vanneste, D.; Permingeat, M. Tools for Managing WHS: Site Management Systems (MS) and Plans (MP) Assessed. In MOOC Tourism Management at UNESCO World Heritage Sites, V2.0. 2018. Chapter 8. Available online: https://www.fun-mooc.fr/ (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- UNESCO. World Heritage Centre World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tourism/ (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Di Giovine, M.A. World Heritage and Tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-3-319-01669-6. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines; World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, A. Managing Tourism at World Heritage Sites: A Practical Manual for World Heritage Site Managers; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Siamak, S.; Hall, M.C.; Fagnoni, E. Managing World Heritage Site Stakeholders: A Grounded Theory Paradigm Model Approach. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. World Heritage Convention The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 1992–2025. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- UNESC World Heritage Centre. WHC Nomination Documentation La Grand-Place de Brussels; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. WHC Nomination Documentation Notre Dame Cathedral in Tournai; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. World Heritage Scanned Nominations; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- City of Brussels; Capital Region of Brussels. The Grande-Place in Brussels, Unesco Heritage Management Plan 2016–2021; Public Heritage Department, Historical Heritage Unit: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Onroerend Erfgoed Vlaanderen Antwerpen—Museum Plantin-Moretus (Vrijdagmarkt). Available online: https://plannen.onroerenderfgoed.be/plannen/1677 (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Visit Bruges Press Feiten en Cijfers over Brugge. Available online: https://press.visitbruges.be/nl/brugge-beleven/feiten-en-cijfers (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Lammens, M. 7 Op de 10 Bewoners van Onze Vlaamse Kunststeden Steunen Toerisme in Hun Stad. Available online: https://toerismevlaanderen.be/nl/nieuws/bewonersonderzoek-2023#:~:text=Inwoners%20staan%20over%20het%20algemeen,het%20vorige%20bewonersonderzoek%20 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- 109 Destinations Rated. Ranking the Globe’s Historic Destinations. 3.Belgium. Historic Center of Ghent (Score: 81); National Geographic Traveller Magazine: Ghent, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Janusz, K.; Six, S.; Vanneste, D. Building tourism-resilient communities by incorporating residents’ perceptions? A photo-elicitation study of tourism development in Bruges. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, D. The preservation of nineteenth-century industrial buildings near historical city centres: The case of Ghent. Acta Acad. 2004, 36, 157–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistiek Vlaanderen Overnachtingen Door Verblijfstoeristen. Available online: https://www.vlaanderen.be/statistiek-vlaanderen/toerisme/overnachtingen-door-verblijfstoeristen (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Federale Overheidsdienst Binnenlandse Zaken. Bevolkingscijfers per Provincie en per Gemeente op 1 Januari 2023; Federale Overheidsdienst Binnenlandse Zaken: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2023.

- Visit Brussels. Jaarlijks Rapport 2023; Visit Brussels: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- Statbel. TOERISTISCHE AANKOMSTEN EN OVERNACHTINGEN PER GEMEENTE—MEER CIJFERS. Available online: https://statbel.fgov.be/nl/themas/ondernemingen/horeca-toerisme-en-hotelwezen/plus (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Statbel Bevolking. Available online: https://statbel.fgov.be/nl/themas/census/bevolking/bevolking (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Sleutjes, B.; Klingen, J.; Fedorova, T.; Foeken, G.; Orlemans, I.; de Jong, I. Toerisme MRA 2023–2024; Gemeente Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. Available online: https://openresearch.amsterdam/image/2024/6/10/toerisme_mra_2023_2024.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Smits, A. Bevolking in Cijfers. Available online: https://onderzoek.amsterdam.nl/artikel/bevolking-in-cijfers-2024 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Observatori del Turisme a Barcelona Key Figures of Tourism Activity in Destination Barcelona. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiZjcxYTZkMDItMzI3NS00OTFmLWE1ZDMtOGY0M2IwYTM5YmNkIiwidCI6IjliMWM4ZWU3LTIwZWUtNDk0YS1hZjVmLTU4MzYxOTA2ZTU2NyIsImMiOjl9&pageName=ReportSection5cc577c00e480b2cd460 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Info Barcelona. The City’s Population Continues to Grow and Reaches 1.7 Million. Available online: https://www.barcelona.cat/infobarcelona/en/tema/city-council/the-citys-population-continues-to-grow-and-reaches-1-7-million_1405179.html (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Yearbook of Tourism Data 2023; Citta’ di Venezia/City of Venice. 2024. Available online: https://www.comune.venezia.it/sites/comune.venezia.it/files/documenti/Turismo/Yearbook_of_tourism_data_2023.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Statista Number of Inhabitants of Venice from 1871 to 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1454398/inhabitants-venice-municipality/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).