Variations in Hiroshige’s Print “The Plum Garden at Kameido”

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Photographs of “The Plum Garden at Kameido”

2.2. Analytical Techniques

2.2.1. Digital Microscopy

2.2.2. FORS

2.2.3. Raman Spectroscopy

2.2.4. XRF

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Colourants

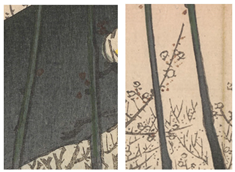

3.2. Fading

3.3. Number of Woodblocks

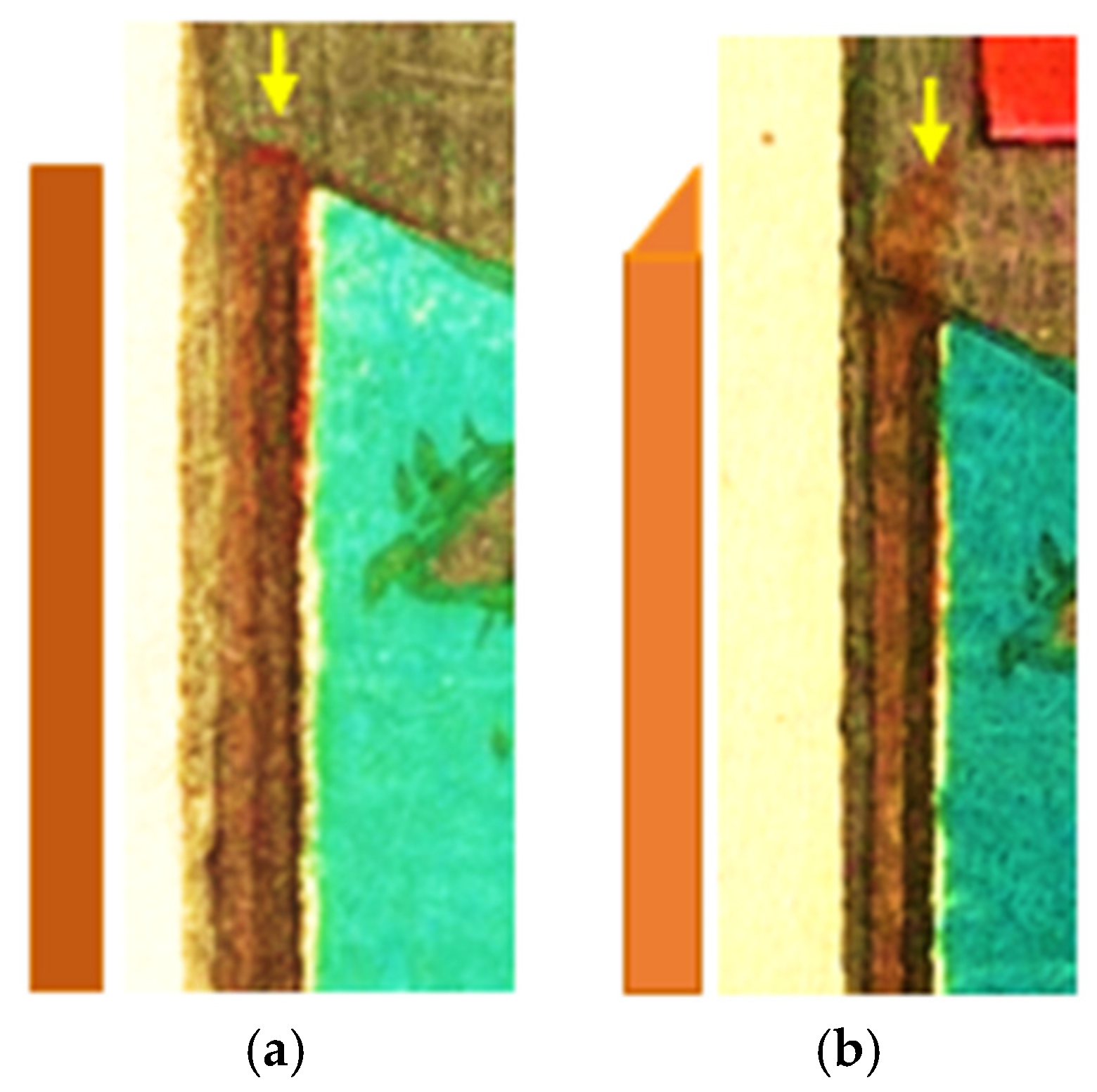

3.4. Woodblock Wear Study

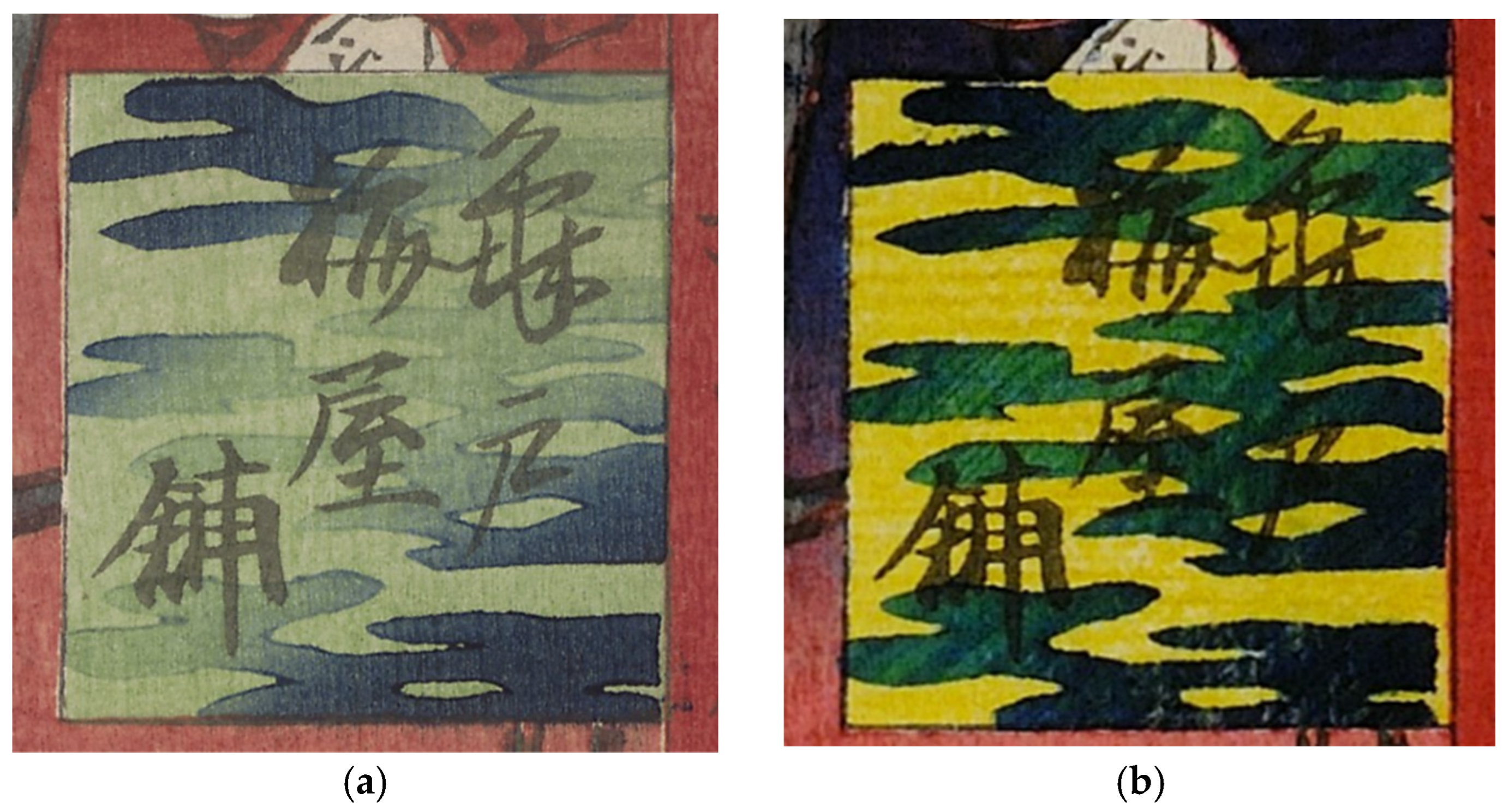

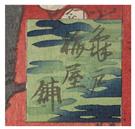

3.5. The Four States of Hiroshige’s Design

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Art Institute of Chicago |

| BM | British Museum |

| FORS | Fibre optic reflectance spectroscopy |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

References

- Uhlenbeck, C. L’estampe japonaise: Un art commercial, multiple, créatif et immense. In Les Plus Belles Estampes Japonaises; Vandeperre, N., Ed.; Snoeck: Gand, Belgium, 2016; pp. 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ōkubo, J. On Ukiyo-e Publishing; Yoshikawa Kōbunkan: Tokyo, Japan, 2013. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, M.; Burgio, L.; Vandeperre, N.; Driscoll, E.; Viljoen, M.; Woo, J.; Leona, M. Beyond the connoisseurship approach: Creating a chronology in Hokusai prints using non-invasive techniques and multivariate data analysis. Herit. Sci. 2020, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenberg, C.; Derrick, M.; Pereira Pardo, L.; Matsuba, R. Establishing the production chronology of the iconic Japanese woodblock print ‘Red Fuji’. Art Sci. 2021, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenberg, C. The making and evolution of The Great Wave. In Late Hokusai: Society, Thought, Technique, Legacy; Clarke, T., Ed.; British Museum Research Publications: London, UK, 2023; pp. 192–211. [Google Scholar]

- Tokuno, T. Japanese wood-cutting and wood-cut printing. In Report of National Museum; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1892; Available online: https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/29868/Tokuno_1892_221-244.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Ishii, K. The Engraving and Printing of Japanese Prints; Geisodo: Kyoto, Japan, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Furuhata, C.; Kato, E.; Sagawa, Y. The Anatomy of Colors: Look Closely and Read the Stories of Colors of Edo in Kuniezu & Ukiyoe; The Meguro Museum of Art: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Kanada, M. Color Woodblock Printmaking. The Traditional Method of Ukiyo-e; Shufunotomo: Tokyo, Japan, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Leona, M.; Winter, J. Fiber optics reflectance spectroscopy: A unique tool for the investigation of Japanese paintings. Stud. Conserv. 2001, 46, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Arantegui, J.; Rupérez, D.; Almazán, D.; Díez-de-Pinos, N. Colours and pigments in late ukiyo-e art works: A preliminary non-invasive study of Japanese woodblock prints to interpret hyperspectral images using in-situ point-by-point diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Microchem. J. 2018, 139, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafana, T.; Edwards, G. Creation and reference characterization of Edo period Japanese woodblock printing ink colorant samples using multimodal imaging and reflectance spectroscopy. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, C.; Mounier, A.; Pérez Arantegui, J.; Le Bourdon, G.; Servant, L.; Chapoulie, R.; Roldán, C.; Almazán, D.; Díez-de-Pinos, N.; Daniel, F. Colours of the «images of the floating world». Non-invasive analyses of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints (18th and 19th centuries) and new contributions to the insight of oriental materials. Microchem. J. 2020, 152, 104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukiyo-e Search. Available online: https://ukiyo-e.org (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Korenberg, C. How to determine the production chronology of a Japanese woodblock print. Andon 2022, 113, 42–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yamato, A. Studies on Changes in the Colorants Used in Later Ukiyo-e Prints; Tohoku University of Art and Design: Yamagata, Japan, 2013. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, M.; Tamburini, D.; Müller, E.; Centeno, S.A.; Basso, E.; Leona, M. Integrating liquid chromatography mass spectrometry into an analytical protocol for the identification of organic colorants in Japanese woodblock prints. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caggiani, M.C.; Cosentino, A.; Mangone, A. Pigments Checker version 3.0, a handy set for conservation scientists: A free online Raman spectra database. Microchem. J. 2016, 129, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, B.; Stiber Morenus, L. Ultraviolet and Infrared Examination of Japanese Woodblock Prints: Identifying Reds and Blues. In The Book and Paper Group Annual 23; The American Institute for Conservation: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann, G.; Richter, M. Types of dry-process artificial arsenic sulphide pigments in cultural heritage. In Fatto d’Archimia: Historia e Identificación de los Pigmentos Artificiales en las Técnicas Pictóricas; del Egido, M., Kroustallis, S., Eds.; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2012; pp. 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, D.G.; Boolchand, P.; Jackson, K.A. Intrinsic nanoscale phase separation of bulk As2S3 glass. Philos. Mag. 2003, 83, 2941–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, M.; Leona, M. Evidence of early amorphous arsenic sulfide production and use in Edo period Japanese woodblock prints by Hokusai and Kunisada. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conservation and Art Materials Encyclopedia Online. Ukiyo-e Print Colorant Database. Available online: https://cameo.mfa.org/wiki/Ukiyo-e_Print_Colorant_Database (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Tamburini, D.; Dyer, J. Fibre optic reflectance spectroscopy and multispectral imaging for the non-invasive investigation of Asian colourants in Chinese textiles from Dunhuang (7th–10th century AD). Dye. Pigment. 2019, 162, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, M.; Janssens, K.; Sanyova, J.; Rahemi, V.; McGlinchey, C.; De Wael, K. Assessing the stability of arsenic sulfide pigments and influence of the binding media on their degradation by means of spectroscopic and electrochemical techniques. Microchem. J. 2018, 138, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padfield, T.; Landi, S. The Light-fastness of the Natural Dyes. Stud. Conserv. 1966, 11, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meech-Pekarik, J. Frank Lloyd Wright and Japanese prints. Metrop. Mus. Art Bull. 1982, 40, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozumi, T. Hokusai Returns: Japan’s Greatest Ukiyo-e Artist; Tokyo Broadcasting System: Minato City, Japan, 1987. [Google Scholar]

| Location | Institution |

|---|---|

| France (1) | Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris (FRBNF43789439) |

| Germany (3) | Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg (IE1897.1) Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne (R54,14(58)) Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden |

| Ireland (1) | Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (J 2693) |

| Israel (1) | Tikotin Museum, Haifa (P-U1029) |

| Italy (2) | Museo d’Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone, Genoa Museo d’Arte Orientale, Venice (2700_12475-83) |

| Japan (12) | Edo-Tokyo Museum Isago no Sato Museum, Kawasaki Mogi-Honke Museum of Art, Chiba Nara Prefecture Museum National Diet Library, Tokyo (10.11501/1312266) Ota Memorial Museum of Art, Tokyo Shimane Art Museum, Matsue Shizuoka City Museum of Art Tokyo Fuji Art Museum (1171) Tokyo National Museum (2 impressions) Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum of Waseda University (201-1377) |

| Netherlands (2) | Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-P-1956-743) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (n0077V1962-800) |

| Poland (2) | National Museum, Krakow National Museum, Warsaw |

| UK (4) | British Museum, London (1954,1113,0.29, 1948,0410,0.65 and 1915,0823,0.692) Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (P.3562-R) |

| US (21) | Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin (1950.1396) Art Institute of Chicago (1925.3752, 1939.1405 and 1965.1027) Brooklyn Museum, New York (30.1478.30_PS1) Cantor Arts Center, Stanford (1984.473) Chazen University of Wisconsin, Madison (1980.1608) Clark Art Institute, Williamstown (2014.16.13) Fine Arts Museum San Francisco (54755.752) Honolulu Museum of Art (24103, 11490, 22721 and 24104) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (06.635, 11.2223, 11.20206, 11.35818, 11.45649 and 21.10421) Seattle Art Museum (2017.23.22) Worcester Art Museum (1901.59.1244) |

| Auction houses and galleries (29) | Christie’s, several locations (13 impressions) Egenolf Gallery Japanese Prints, Los Angeles Hartman Galleries, New York Heritage Auctions, London Hotel Drouot, Paris Japanese Prints, London Reeman Dansie, Colchester Ronin Gallery, New York (4 impressions) Sotheby’s, several locations (5 impressions) Yamada Shoten, Tokyo |

| Others (4) | Private collection (2 impressions) Book “Japanese Prints & Drawings from the Vever Collection” by Jack Hillier, 1976, Sotheby’s Publications: New York Book “Hiroshige” by Walter Exner, 1960, Methuen: London |

| Colour | Colourants |

|---|---|

| Blue | Ai (indigo), bero-ai (Prussian blue), aobana (dayflower) |

| Yellow | Kihada (armur cork tree), sekiō (orpiment), ōdo (earth pigment), tōō (gamboge), ukon (turmeric), zumi (briar or crabapple) |

| Red | Bengara (earth pigment), beni (safflower), shōenji (lac), shu (vermillion), suō (sappanwood), tan (red lead) |

| Black | Sumi (plant soot) |

| White | Enpaku (white lead), gofun (shell white) |

| Colour | BM 1954 | BM 1948 | BM 1915 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue | Prussian blue | Prussian blue | Prussian blue |

| Green | Prussian blue and arsenic sulphide | Prussian blue and arsenic sulphide | Prussian blue and arsenic sulphide |

| Yellow | Arsenic sulphide | Arsenic sulphide | Turmeric * |

| Red | Safflower * and vermillion | Safflower * and vermillion | Safflower * and vermillion |

| Purple | Prussian blue and safflower * | Dayflower * and safflower * | Prussian blue, vermillion and safflower * |

| Colour | Areas | Illustrations |

|---|---|---|

| Black | Outlines and clothes of visitors (key block) | |

| Grey 1 | Trees’ trunks and branches, teahouse, clothes of visitors | |

| Green | Four thin branches in foreground |  |

| Dark grey | Dark areas on trees (bokashi) |  |

| Yellow 1 | Flower hearts and roof of tea house (also used to apply brown bokashi on roof) |  |

| Pink | Sky (also used for the red bokashi in the sky) | |

| Green 1 | Grass (also used for the blue bokashi in the grass and the green bokashi by the fence) |  |

| Green 2 | Clothes of two visitors |  |

| Green 3 | Background of title cartouche |  |

| Red | Cartouches for artist signature and series title |  |

| Brown 1 | Wooden sign in top left corner and beam of teahouse |  |

| Brown 2 | Buds |  |

| Beige | Benches and heads of some visitors |  |

| Blue 1 | Pattern on title cartouche |  |

| Blue 2 | Clothes of one visitor |  |

| Blue 3 | Clothes of four visitors |  |

| State | Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blue bokashi in grass, brown bokashi on the teahouse roof, circular shape of flower’s heart in area A, red sky, green title cartouche background | BM 1954, Rijksmuseum, Tikotin Museum |

| 2 | Triangular shape of flower’s heart in area A | BM 1948, Fitzwilliam Museum, Chester Beatty Library |

| 3 | Missing flower’s heart in area A (sometimes in other areas as well) | Chazen University of Wisconsin, Shimane Museum |

| 4 | Blue/purple at top of the sky, missing flower’s heart in area A (sometimes in other areas as well), yellow title cartouche background cartouche, use of new red woodblock as seen by small defects in areas A and E | BM 1915, National Diet Library |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korenberg, C. Variations in Hiroshige’s Print “The Plum Garden at Kameido”. Heritage 2025, 8, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8020074

Korenberg C. Variations in Hiroshige’s Print “The Plum Garden at Kameido”. Heritage. 2025; 8(2):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8020074

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorenberg, Capucine. 2025. "Variations in Hiroshige’s Print “The Plum Garden at Kameido”" Heritage 8, no. 2: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8020074

APA StyleKorenberg, C. (2025). Variations in Hiroshige’s Print “The Plum Garden at Kameido”. Heritage, 8(2), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8020074