Abstract

Maritime cultural heritage (MCH) in Greece remains poorly explored and underutilized due to several key challenges, including the dispersed locations of heritage sites, limited community engagement in decision-making, and the absence of a well-structured decentralized governance framework. This paper addresses these issues by focusing on strategic planning and social management to better integrate coastal and maritime heritage sites into both tourism development and the everyday life of local communities. Our research examines the creation of local social networks and participatory decision-making processes, as well as the adoption of innovative solutions such as maritime spatial planning (MSP) and soft projects to connect scattered cultural sites into cohesive, integrated clusters. The aim is to foster tourism and economic development through collaboration with local stakeholders. The findings emphasize the establishment of a social network for cultural heritage management in the West Pagasetic region of Magnesia, Greece, which culminated in a strategic plan to link cultural sites through soft projects and consultations. This process included a participatory workshop and the creation of a Community of Practice (CoP) that brought together professionals from the heritage, tourism, and planning sectors.

1. Introduction

The current case study analysis belongs to the project entitled “Developing an Observation Network for Maritime Cultural Heritage (hereinafter MCH, incl. underwater cultural heritage, hereinafter UCH) in Greece” [1]. This project developed a typology on how to embed and utilize maritime cultural heritage for MSP purposes [2,3,4] in two different territorial and maritime contexts, i.e., the island context of the Dodecanese complex in South Aegean Sea and the land–sea context of the Pagasetic Gulf in the Thessaly region. Specifically, the research project targeted the incorporation of social and cultural values into Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP), through participatory processes and to support blue economy goals. Whilst the importance of cultural and heritage values associated with the sea is gaining increasing recognition, these intangible benefits (e.g., cultural identity, marine identity, esthetic appreciation, and personal and community perceptions) are often overlooked in MSP due to the challenges associated with defining and connecting them to specific locations. The project sought to address this gap in Greece, which is endowed with a rich maritime cultural heritage (MCH) and underwater antiquities. Greece, with its long maritime tradition, high coastality and insularity, offers a unique context for studying the intersection of marine ecosystems and cultural heritage.

Regarding the two case studies involved in this research, different methodologies have been applied because the areas are different in terms of territorial context and scale, population scale, as well as major concerns by local society and local communities.

1.1. About Maritime Cultural Heritage and Its Integration in MSP

Cultural heritage plays a multifaceted role in contemporary society, offering valuable insights into historical contexts while also supporting the sustainability of both rural and urban communities [5]. By preserving and promoting cultural heritage, societies increase their understanding of social evolution, safeguarding the continuity of traditions and consolidating their cultural identities. Beyond its historical and identity-building implication, cultural heritage contributes to community sustainability by strengthening social cohesion, supporting tourism, and driving local economic development. This role becomes even more pronounced in regions with an intercultural history that transcends national borders. A typical example is the Mediterranean region, often likened to a “great lake” of cultures, where centuries of trade and interaction have facilitated a rich exchange of ideas, practices, and traditions, shaping its diverse and interconnected cultural landscape.

Human interaction with the seas and oceans, particularly in coastal areas, has played a crucial role in shaping both the natural landscape and the development of maritime cultural heritage. This heritage spans not only terrestrial and marine elements but also includes underwater environments, creating a rich and diverse tapestry that forms an essential part of our collective cultural resources [6]. Over centuries of engagement with the coastal and marine world, these heritage sites provide invaluable insights into human history, innovation, and the intricate relationship between people and the sea [7].

Within the broader spectrum of cultural heritage, Maritime Cultural Heritage (MCH) holds a unique and vital position. MCH is the cultural outcome of the interactions between people, societies, and their maritime environments, as well as their links to broader maritime trade networks. On a larger scale, maritime heritage reflects the remnants of sea-borne connections, including trading ports, artifacts, and shipwrecks. While contemporary maps often depict major rivers, large water bodies, and oceans as uninhabited regions that define geopolitical boundaries, these maritime spaces have historically been areas of intense interaction and connectivity. This exchange of people, ideas, and material culture across these regions led to the development of complex cultural imaginaries over vast distances. This is evident in the historic trade and religious networks of the Maritime Silk Road, which stretched from Japan and China in the east to Europe and the Middle East in the west. The historic ports along these networks were shaped by the diverse populations that lived in and traveled through them over the centuries [8].

According to [9], Maritime Cultural Heritage consists of finite and non-renewable cultural resources, including prehistoric and indigenous archeological sites and landscapes along coastlines or submerged underwater, historic waterfront structures, remnants of seagoing vessels, and both past and present maritime traditions and ways of life. Therefore, MCH includes both tangible and intangible elements such as narratives, practices, traditions, customs, cultural imagery, which may be found either on land or underwater, and the physical landscapes shaped by maritime culture. These components represent the deep connection between people, the sea, and their environment, carrying not only cultural and emotional significance but also practical value and a variety of other meanings [8].

“Underwater Cultural Heritage” (UCH) is a subset of maritime cultural heritage which specifically focuses on the tangible assets and resources found beneath the water. This includes (a) submerged archeological sites such as shipwrecks, sunken cities, and prehistoric landscapes that are now underwater due to rising sea levels, (b) artifacts and remnants such as objects left behind by past civilizations, which may include pottery, tools, and personal belongings that were submerged [5].

According to what was mentioned above, maritime/underwater cultural heritage (MUCH) refers to the tangible and intangible elements related to human interaction with the sea and other bodies of water, spanning from ancient times to the present day. According to the recent Global International Guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning [10], maritime/underwater cultural heritage (MUCH) is a key consideration in MSP efforts. MUCH encompasses both tangible and intangible aspects of human history and the significance of this heritage lies not only in its historical value but also in its potential to contribute to social and cultural identities, engage local stakeholders, and support economic development through cultural tourism.

Integrating MCH into Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP) helps preserve cultural assets, support sustainable development, and enhance the identity of local maritime communities. This can be achieved by identifying and mapping cultural resources, engaging stakeholders, implementing conservation-based legal provisions, ensuring sustainable use, and monitoring heritage sites. By considering cultural heritage alongside other marine uses, MSP can safeguard both environmental and cultural values.

The following Table 1 summarizes the different steps of integration of MCH in MSP, resulting from desk research from various relevant papers and reports.

Table 1.

Basic steps towards better integration of MCH in MSP.

1.2. Maritime Cultural Heritage in Greece

Maritime/underwater cultural heritage is a critical component of Greece’s rich historical tapestry, offering profound insights into the nation’s interactions with the sea and its surrounding environment over millennia. In the context of unresolved conflicts among neighboring countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea, nowadays, MUCH may act as a critical catalyst in the field of cultural diplomacy. As stated by [11,12], cultural diplomacy continues to attract significant interest as a potential means for states to exercise “soft power”. However, the concept of “soft power” has, thus far, yet to be applied more broadly in cultural heritage studies [13,14,15].

Despite its significant cultural and economic potential, MUCH faces significant challenges. It is made up of finite and non-renewable cultural resources, including both coastal and submerged archeological sites, as well as the maritime traditions and ways of life of past and present communities. Nevertheless, several key issues hinder the effective management and utilization of these resources, including the dispersed nature of heritage sites, which often renders them inaccessible; the lack of involvement of local communities and professional associations in tourism-related decision-making; and the absence of decentralized governance and effective monitoring mechanisms for cultural heritage management.

Greece has a tough legislative framework for the protection and management of underwater cultural heritage (UCH), which is reflected in numerous laws, conventions, and regulations aimed at preserving these valuable assets. The legislative landscape draws from international conventions as well as national legal provisions.

As for the international conventions and agreements, and more specifically the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the UCH (2001) [16], Greece ratified this convention, aspiring to protect UCH from activities that could spoil it. The convention sets out general principles and guidelines, involving the prevention of commercial utilization of UCH and the promotion of scientific research for its conservation. Furthermore, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) [17] offers a framework for the regulation of maritime areas, including provisions related to the protection of submerged heritage. Greece, being a signatory party of UNCLOS, follows the instructions fixed by this Convention in the management of maritime archeological sites. On the other hand, Greece, as an EU member state, is subject to European Union regulations and directives on cultural heritage, including the EU’s Cultural Heritage Policies, emphasizing the preservation of UCH.

In 1976, a specialized service was established within the Hellenic Ministry of Culture entitled “Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities” [18]. This service is responsible for overseeing underwater cultural heritage across the country. Its primary mission is to safeguard underwater antiquities, which include ancient shipwrecks, submerged settlements, and historical harbor structures found in the seas, lakes, and rivers.

The basis of Greece’s cultural heritage protection system is law 3028/2002 [19], which establishes the legal framework for the protection of cultural heritage, including both terrestrial and underwater sites. It ensures that underwater archeological sites, such as shipwrecks, sunken cities, and submerged artifacts, receive the same level of protection as land-based heritage. Article 2 of the law specifically addresses the preservation of underwater cultural heritage, granting the Greek Ministry of Culture exclusive authority over permits for exploration or excavation.

Since 2003, with the designation of shipwrecks and aircrafts over 50 years old as monuments of historical, technical, scientific, and cultural significance [20], the Ephorate mentioned above has also been tasked with their protection. Specifically, the Ephorate’s responsibilities include (a) the identification and exploration of submerged antiquities; (b) ensuring their preservation; (c) organizing underwater antiquities museums; (d) overseeing projects conducted by maritime research institutions, oceanographic centers, and expeditions; (e) regulating diving and other maritime activities that may pose risks to the preservation of antiquities; (f) promoting the designation of underwater archeological sites (article 15 of Law 3028/2002 [19]); and (g) managing and maintaining these sites as publicly accessible locations under supervision (AUCHS), according to Article 11 of Law 3409/2005 [21]. Besides, in 2015, the Ministry issued additional guidelines to regulate underwater archeological research, specifying who may conduct such activities (e.g., licensed archeologists) and the conditions for obtaining exploration permits.

Finally, an important legislative amendment has recently been enacted, creating a new, functional institutional framework for underwater cultural heritage and recreational diving. The amendment to Law 3409/2005 [18] was followed by the enactment of Law 4688/2020 [22], which introduced provisions for special forms of tourism, including the establishment of “underwater museums”. This law was later incorporated into Law 4858/2021 [23], which codified the legislation for the protection of antiquities and cultural heritage in general.

Under the revised legal framework, recreational diving is still permitted in Accessible Underwater Archeological Sites (AUAS), but a new operational model has been developed. According to this model, the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities is responsible for the management, organization, operation, and safety of these underwater sites. Diving service providers, licensed and approved by the Ministry, oversee escorting groups of divers and ensure their safety while visiting the sites. These providers are required to employ specially trained guides, who are authorized by the Ministry and tasked with educating divers on proper conduct at these sensitive locations.

Furthermore, Article 7 of the Law 4688/2020 [22] permits recreational diving at shipwrecks, which are considered a subcategory of underwater cultural heritage. These wrecks can only be accessed following their official designation as “accessible” through a Joint Ministerial Decision, which also sets out the specific conditions for diving at these sites. To date, 91 modern historic shipwrecks have been designated as accessible by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, and efforts are underway to open them to the public [24].

In certain cases, Greece has also established marine protected areas (MPAs) considered in parallel zones for the preservation of UCH [25]. These include areas with significant archeological value. Commercial exploitation of underwater cultural heritage (such as treasure hunting) is prohibited under both Greek law and the UNESCO Convention. The law strictly regulates the recovery of underwater artifacts and mandates that any discoveries of cultural heritage be reported to the authorities. Finally, only certified archeologists, researchers, or institutions authorized by the Ministry of Culture can carry out underwater excavations or research. This includes a formal process for granting permits for archeological investigation in maritime areas. Greece also encourages scientific research and international collaboration in the field of underwater archeology. Researchers and international teams often work under permits and with the approval of the Ministry of Culture, ensuring that their activities comply with national laws and international obligations.

Greece also emphasizes the educational and cultural importance of maritime and underwater heritage. Artifacts recovered from the sea can be displayed in museums or used for public outreach, following preservation and conservation guidelines. The country has founded strict enforcement mechanisms to protect UCH. Any illegal excavation or trade in underwater cultural objects can result in severe penalties, including fines, confiscation of artifacts, and imprisonment. The Greek Coast Guard and local authorities often collaborate with archeologists to ensure compliance with these laws in maritime zones.

In conclusion, Greece’s legislative framework on Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage is comprehensive and is aligned with both international and national standards for cultural heritage protection, but also considers other marine activities. The combination of specific laws, international conventions, regulatory bodies like the “Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities”, and enforcement measures ensures that underwater cultural heritage is properly safeguarded for future generations.

Despite the above, the challenges facing the effective management of MUCH in regions like the West Pagasetic Gulf, located in Magnesia, Greece, are manifold. They include the physical dispersion of sites, which limits accessibility and integration into the everyday lives of residents and tourists alike. Furthermore, the governance of these sites is often fragmented, with overlapping responsibilities among various authorities, leading to inefficiencies in planning and management. Additionally, there is a notable lack of societal participation in the decision-making processes related to cultural heritage, which hinders the development of community-driven initiatives that could enhance the value and accessibility of these sites.

Hence, this paper aims to address these challenges by exploring strategic planning and participatory social management approaches tailored to the unique context of the area. The research focuses on two primary objectives: (a) the creation of local social networks and participatory processes for decision-making and cultural heritage management, and (b) the implementation of innovative solutions, including strategic terrestrial and maritime planning, alongside soft projects designed to link dispersed cultural sites into cohesive cultural clusters. These clusters and networks are intended to improve the visibility and accessibility of cultural heritage, ultimately fostering tourism and economic development in alignment with the interests and needs of local stakeholders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Case Study Area

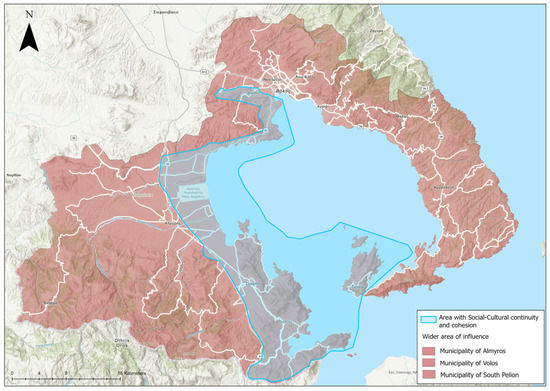

The coastal district and the maritime area in west Pagasetic Gulf represent the pilot research area (Figure 1). The West Pagasetic Gulf is a coastal area in the region of Magnesia, which is one of the 74 regional units of Greece. The regional unit of Magnesia is a subdivision of the Region of Thessaly and consists of the municipalities of Almyros, Volos, Zagora-Mouresi, South Pelion, and Riga Feraiou, though it does not include the regional unity of Sporades islands. Magnesia has an area of 2636 sq. km and the total population of the regional unit amounts to 177.448 inhabitants, according to the 2021 census. The capital of the regional unit is the city of Volos with a population of 139.670 inhabitants. The second-largest city in terms of population is the municipality of Almyros, a mainly rural area with a population of 16.072 inhabitants.

Figure 1.

The pilot case study area, located in the West Pagasetic Gulf.

The case study area (Figure 1) extends from the outskirts of Volos up to Amaliapolis and opposite to it, up to the village and the Island of Trikeri in the south Pelion peninsula. It is a coastal and maritime area of 40 km in length and 5 km in width, and it constitutes a large cluster of important heritage sites from different historical periods: the prehistoric period, Classical Antiquity, Hellenistic centuries, and the Byzantine Age. This broad research area transverses three municipalities: the Municipality of Volos, the Municipality of Almyros, and the Municipality of South Pelion.

The focused research area (Figure 1), highlighted in light blue, contains archeological heritage sites and intangible cultural elements spanning 3000 years of history. The cultural cluster includes neolithic and prehistoric settlements (Sesklo, Dimini, Neilia, Nies), ancient cities from Classical Antiquity (Iolkos, Demetriada, Pyrassos, Alos), Byzantine cities, convents, and churches (such as Fthiotides-Thebes and the Convent of Panagia Xenia), as well as shipwrecks from the Classical Antiquity and Byzantine Eras.

The region of Magnesia, characterized by its centuries-old and historically significant heritage, was chosen for the establishment of a unified coastal cultural zone. This research focuses on an area rich in monuments of cultural significance, historical landmarks, and archeological sites. According to the National Archive of Monuments [26], which records and documents the monuments, archeological sites, historical sites and protection zones of Greece, the study area (Figure 1) includes over 40 declared protected areas.

The selected zone demonstrates strong socio-cultural continuity and cohesion, with deep-rooted economic, commercial, and communicative interdependencies, evidenced by the numerous archeological discoveries.

It is known that on the coasts of Magnesia and the Northern Sporades, important events took place in ancient times that left their mark on history. According to mythology, the Argo, the ship used by the Argonauts for their famous campaign, was built in this area. In addition to various historical events, the area was also known for its busy sea routes. Having dry land on either side made travel safer, while the affluent societies living in the area contributed to developing trade. Both historical sources and archeological finds highlight that Magnesia and the Northern Sporades played an important role in ancient Greece, both historically and economically [24]. Within this expansive cluster of cultural heritage sites, three distinct subclusters can be identified (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Subclusters of the research area.

- A

- The subcluster of Pefkakia, including the prehistoric towns of Nileia and Iolkos, the Hellenistic city of Dimitriada, the Neolithic village of Dimini, and the prehistoric village of Sesklou.

- B

- The subcluster of Nea Anghialos, including the ancient cities of Pyrasos (Classical antiquity) and Fthiotides-Thebes of the Byzantine Age (3rd AD).

- C

- The subcluster of Almyros–Nies–Amaliada–Trikeri islands including the prehistoric city of Alos, as well as ancient and Byzantine shipwrecks.

2.2. Challenges Related to the Archeological Site

The archeological landscape of the West Pagasetic Gulf is divided into distinct subclusters, each characterized by unique historical significance and varying degrees of accessibility. The Pefkakia subcluster includes the prehistoric settlements of Nileia and Iolkos, along with the Hellenistic city of Dimitriada. This area is notably isolated and disconnected from the local street network, which renders the archeological sites inaccessible to the public. Although there have been proposals for two projects aimed at developing a pedestrian network to improve public access to these sites, no substantial progress has been made towards their implementation.

In contrast, the Nea Anghialos subcluster, which comprises the ancient city of Pyrasos from Classical Antiquity and Fthiotides-Thebes from the Byzantine era (3rd century AD), is characterized by excellent connectivity and accessibility. These archeological sites are not only easily accessible to visitors but are also well-integrated into the urban fabric of the modern city of Nea Anghialos, thereby enhancing the area’s cultural and historical continuity.

Similarly, the Almyros–Nies–Amaliada–Trikeri Island subcluster, which includes the prehistoric city of Alos as well as ancient and Byzantine shipwrecks, mirrors the isolation observed in the Pefkakia subcluster. The archeological sites in this subcluster are scattered and disconnected from the local street network, making them inaccessible to the public. This lack of accessibility highlights a broader challenge in balancing the preservation of historical integrity with the promotion of public engagement with the region’s rich archeological heritage.

In July 2022, the Greek Ministry of Culture, in collaboration with the Regional Authority of Thessaly and the Municipality of Almyros, presented a list of projects for the area that have been incorporated into the BlueMed European Project [24]. These projects include plans for the construction of three underwater museums, which are intended to create a holistic submarine park that will allow the public to visit ancient shipwrecks.

The planned projects include several key initiatives:

- First, the design of underwater pathways for self-guided divers, accompanied by special tablets suitable for underwater use, will provide information about the underwater archeological remnants as well as the biodiversity of the sea.

- Second, the construction of information centers along the coastal zone will utilize virtual reality software to enable visitors to experience a virtual dive and explore the underwater archeological remnants of shipwrecks.

However, it is important to note that, despite these ambitious plans, none of these projects have been realized thus far. No construction has begun, and the proposed initiatives remain in the initial planning stages. The delay in implementing these projects underscores the ongoing challenges in advancing heritage management and accessibility in the region.

2.3. The Research Methodology

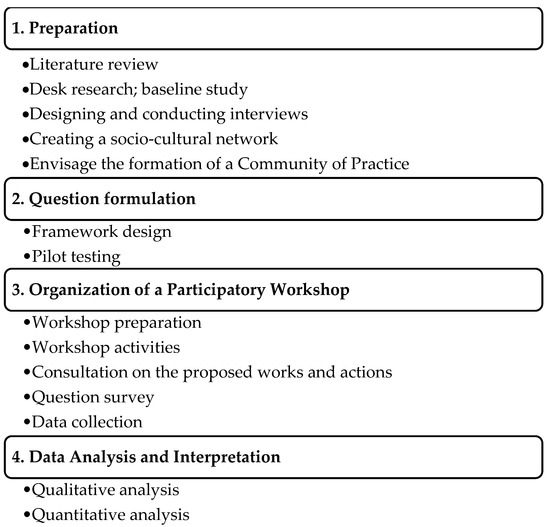

The 2024 pilot research in the West Pagasetic Gulf, Magnesia, Greece, was carefully designed to investigate strategic planning and participatory social management of MCH. The study followed a structured, step-by-step approach aimed at improving the management and utilization of dispersed cultural sites, with the goal of better integrating them into both tourism development and the daily lives of local communities. The methodological framework comprised several key actions, outlined as follows (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The research process.

2.3.1. Preparation

The preparation phase involves a comprehensive approach to understanding the existing landscape of MCH in the West Pagasetic Gulf. This phase includes a literature review, a desk research and baseline study, representative stakeholders’ interviewing, the creation of a socio-cultural network, and the formation of a Community of Practice with practitioners from the planning, heritage and tourism sectors.

Literature Review

A thorough review of the existing literature is conducted to identify key themes, methodologies, and outcomes related to MCH management. This review provides a theoretical framework for the study, drawing insights from global and local case studies that illustrate best practices in strategic planning and participative social management of dispersed cultural heritage sites.

Desk Research Baseline Study

The baseline study focuses on mapping the socio-cultural objects in the coastal area of the West Pagasetic Gulf up to inland and assessing their historical significance, accessibility, and current state of preservation. Based on the comprehensive data collected from multiple sources, including cultural heritage registration services, extensive on-site research, a systematic review of historical texts about the region, and interviews with key stakeholders, such as officials from the local Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia and residents, we developed an extensive database cataloging all objects of socio-cultural significance. This meticulous mapping process involved not only the identification and documentation of these cultural assets but also a detailed assessment of their cultural, historical, and social value. The evaluation of each site’s significance was essential in establishing a framework for prioritizing them, ensuring that the most critical and vulnerable heritage assets receive appropriate attention in future conservation, management, and sustainable development strategies. This structured approach aims to facilitate informed decision-making and the integration of cultural heritage into broader regional planning efforts, safeguarding the area’s unique identity while promoting responsible development. Furthermore, this systematic approach enabled us to group these heritage assets into distinct clusters based on shared characteristics such as geographic proximity, thematic connections, or historical significance.

Conducting Interviews

To gain a deeper understanding of local perspectives and identify key issues in MCH management, in-depth interviews were conducted with a diverse range of stakeholders. These stakeholders include local community members, cultural heritage professionals, municipal authorities, tourism operators, fishers, and representatives from non-governmental organizations. The interviews aim to capture insights into the challenges and opportunities associated with cultural heritage management in the region, as well as stakeholders’ expectations and suggestions for future strategies. Τhis stage was performed in parallel with the baseline study in order to create the database with objects of socio-cultural significance.

Creating a Socio-Cultural Network

The initial phase involved creating a robust socio-cultural network to actively engage local communities, stakeholders, and professional associations connected to tourism and cultural heritage. This network was critical for fostering communication, collaboration, and collective decision-making. The socio-cultural network aimed at promoting two central ideas: (a) the West Pagasetic Gulf constitutes a significant cluster of coastal and maritime cultural heritage, and (b) the most effective protection and enhancement of this cultural cluster can be achieved through societal engagement and the establishment of a socio-cultural network. Key participants in the network included local government representatives, cultural and historical associations, archeologists, tourism professionals, and other relevant stakeholders. This network served as the foundation for subsequent activities, ensuring that the research was grounded in local knowledge and perspectives.

Through interviews with various stakeholders, it became clear that enhancing the cultural heritage of the West Pagasetic area, both coastal and maritime, was a shared priority. Stakeholders highlighted several challenges, including the need for funding to complete excavations and brand the area, coordination issues among involved authorities, and significant accessibility difficulties due to inadequate road infrastructure and public transportation. Additionally, the lack of essential visitor infrastructure, such as security, pedestrian pathways, and amenities at archeological sites, was identified as a barrier to making these sites attractive and accessible. All of them have agreed on the significance of cultural heritage in West Pagasetic area, and its critical role in tourism and economic development of Magnesia.

Recognizing the vital role of cultural heritage in driving tourism and economic development, there was broad consensus on the need to address these challenges. To put this initiative into action, a call was issued to establish a socio-cultural network for the West Pagasetic heritage. This call was widely disseminated through emails and phone outreach to a diverse group of stakeholders, including local and regional authorities, professional associations linked to economic and recreational activities, and NGOs focused on cultural heritage preservation. The response was overwhelmingly positive, resulting in the successful creation of the socio-cultural network. Moreover, a Community of Practice was envisaged with the topic of “integrating MUCH in maritime spatial Planning (MSP)” that, in this case, would unite practitioners from the planning, heritage, and tourism sectors.

2.3.2. Question Formulation

A key consideration of this research was to appreciate and evaluate the perspectives of all stakeholders within the socio-cultural network; thus, a comprehensive questionnaire was developed. This questionnaire, consisting of 24 questions, was designed to cover all relevant aspects of the research. The questions addressed the following key areas: (a) the identification of the cultural area’s boundaries, including both coastal land borders and sea borders; (b) stakeholders’ knowledge of existing cultural heritage elements, including both built heritage sites and intangible heritage elements, within the research area; (c) stakeholders’ views on the importance of these cultural heritage elements, allowing for a hierarchy of significance to be established; and (d) stakeholders’ opinions on the contribution of cultural heritage to the region’s economic and tourism development.

The questionnaire was tailored to reach all relevant stakeholder groups in the research area, including local authorities, the Regional Authority of Thessaly, professional associations, NGOs involved in cultural heritage, and residents. The broad scope of the questionnaire necessitated the organization of a participatory workshop to further engage stakeholders and discuss the findings in a collaborative environment.

2.3.3. Organization of a Participatory Workshop, the Aim, the Context, and the Process

To increase stakeholder engagement and refine the strategic planning process, a participatory workshop was conducted. The workshop aimed to convene members of the socio-cultural network to discuss, evaluate, and contribute to the development of strategies for the management of cultural heritage. The workshop’s context was established based on the challenges identified through the questionnaire survey and the overarching need for integrated cultural and spatial planning. The workshop process included structured group discussions, presentations of preliminary strategic concepts, and interactive sessions that encouraged participants to provide feedback and propose new ideas. This participatory approach was essential in ensuring that the strategies developed were aligned with the local context and stakeholder expectations.

The workshop was organized with two primary objectives: (a) conducting the questionnaire survey, as described earlier, and (b) facilitating in-depth consultations among stakeholders. The workshop was meticulously planned and scheduled six weeks in advance to ensure broad participation. The organization process involved the following key actions:

- Invitation process: Invitation letters were sent to all members of the socio-cultural network via email and telephone calls, encouraging them to join the forthcoming workshop.

- Community outreach: A broader outreach was conducted on a local scale, inviting the public to participate in the workshop. This was achieved through posters displayed in public buildings and a social media campaign on Facebook, which ran continuously for four weeks.

The workshop provided a structured environment where participants could engage with the research findings and proposed projects. The context of the workshop included the following activities:

- Presentation of research: The pilot research in the Pagasetic area was introduced as a comprehensive coastal and maritime cluster of cultural heritage. This presentation highlighted the significance and potential of the region as a unified cultural tourism destination.

- Questionnaire distribution: Paper-printed questionnaires were distributed to all participants, allowing them to provide their input in real time.

- In-depth consultation: A discussion was conducted to encourage dialog among participants about the research outcomes, with a particular focus on the proposed projects and actions for enhancing cultural heritage in the West Pagasetic coastal and maritime zone. The aim was to reach a consensus on the most effective strategies for heritage enhancement and tourism development.

The proposed projects and actions for consultation are as follows (Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Proposed projects and actions.

- Using terrestrial and maritime spatial planning to transform the West Pagasetic area into a cultural tourism destination, realizing the desirable condition of culture and tourism; economic development and cohesion of local society and introducing a strategic plan for the holistic management and enhancement of maritime cultural heritage in West Pagasetic. In other words, it is proposed that a network of cultural heritage sites (not a series of single, unconnected, and segregated heritage sites) be created to brand the area of West Pagasetic and reinforce cultural tourism development.

- Establishing maritime public transportation to connect all coastal heritage sites within West Pagasetic by high-speed small vessels departing for the Port of Volos every hour and functioning like hop-on and hop-off public transport for visitors. In addition to this public transport, cruise yachts may organize cultural day cruises to coastal and maritime heritage sites of West Pagasetic.

- The integration of cultural heritage sites into the everyday life of inhabitants and visitors by creating an archeological/historical park in Pefkakia, requiring three main projects:

- The design and construction of a pedestrian network and the necessary infrastructures for visitors (i.e., security guidance, WC., closets, coffee canteen, etc., for visitors) in the archeological zone of Pefkakia.

- The construction of an Exhibition Pavilion, a kind of light construction by metal or/and wood [see typical examples in photos] in the public land of 20 hectares owned by the University of Thessaly and located within the archeological zone of Pefkakia. The pavilion will offer 3D representation of ancient monuments as well as 3D animation about the life in the ancient cities found in the area, videos of the ancient Greek expedition to Troe, etc.

The construction of an open-air theater, a kind of light construction made from metal or/and wood [see typical examples in photos] in a 20-hectare area of public land owned by the University of Thessaly and located within the archeological zone of Pefkakia, has also been proposed. The theater will host ancient Greek Tragedies, classical music concerts, and pop concerts during spring and summer.

The Participatory Workshop was held at the City Hall of the Municipality of Almyros on 15 May 2024. The event was well attended, with more than 30 participants, including local and regional politicians, representatives from professional associations and cooperatives, NGOs, and residents of the area.

3. Results

The questionnaire survey was designed to capture the stakeholders’ perspectives on various aspects of the cultural heritage in the West Pagasetic Gulf. The survey, consisting of 24 questions, covered topics such as the identification of cultural area boundaries, stakeholders’ knowledge of cultural heritage elements, and their views on the importance of these elements and their contribution to economic and tourism development. During the participatory workshop, questionnaires were distributed to all attendees, who were encouraged to complete them on-site. Additionally, to ensure broader community engagement, an electronic version of the questionnaire was made available via Google Forms. This provided an opportunity for Almyros residents who were unable to attend the workshop to take part in the survey. The online form stayed open for a week after the workshop to encourage higher response rates and ensure broad participation from the local community. In total, 45 questionnaires were completed, primarily by local experts and professionals, with a focus on cultural heritage.

3.1. Demographic Profile

Table 2 below, highlights that the demographic composition of the survey respondents reflects a diverse cross-section of the local community, which is essential for capturing a wide range of perspectives on cultural heritage management.

Table 2.

Demographic profile of respondents.

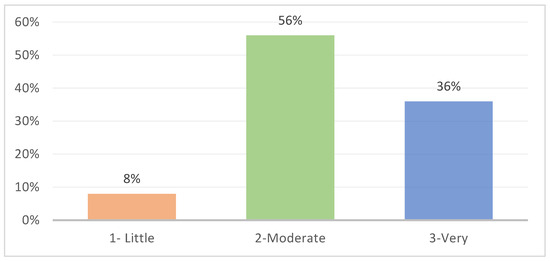

3.2. Awareness and Perception of Cultural Heritage

The respondents demonstrated varying levels of awareness regarding both the built and intangible cultural heritage in the West Pagasetic Gulf.

Built Cultural Heritage Awareness: A significant proportion of respondents (56%) reported a moderate level of awareness of the built cultural heritage in the coastal and maritime zones, with 36% indicating a high level of awareness. Only a small minority (8%) admitted to having little awareness. These findings suggest a relatively strong familiarity with the region’s physical cultural assets among the local population (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Awareness on built cultural heritage.

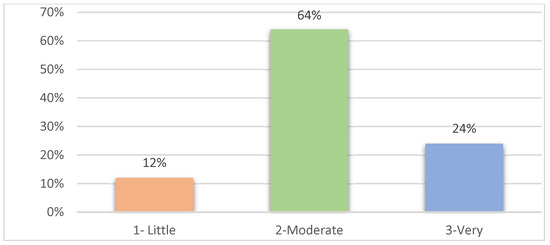

Intangible Cultural Heritage Awareness: When asked about intangible cultural heritage, including music, dances, festivals, and customs, 64% of respondents expressed moderate awareness, while 24% reported high awareness. These results indicate a deep-rooted recognition of the cultural traditions and practices that contribute to the region’s identity (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Awareness of intangible cultural heritage.

3.3. Importance of Cultural Heritage Elements

Participants were asked to identify the cultural heritage elements they deemed most significant for the identity of the Gulf. The results highlight key elements from both built and intangible heritage.

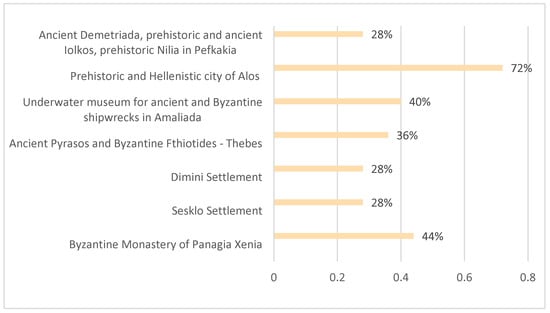

Built Cultural Heritage: The Prehistoric and Hellenistic city of Alos emerged as the most significant element, with 72% of respondents identifying it as a critical part of the region’s heritage. Other important sites included the Underwater Museum for ancient and Byzantine shipwrecks in Amaliada (40%) and the Byzantine Monastery of Panagia Xenia (44%). These findings underscore the historical and cultural significance of these sites and their potential role in cultural tourism (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Importance of built cultural heritage elements.

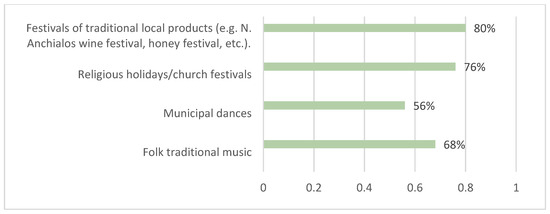

Intangible Cultural Heritage: Among the intangible cultural elements, festivals involving traditional local products were considered the most important by 80% of respondents, followed by religious holidays (76%) and traditional folk music (68%). These preferences reflect the strong cultural traditions that continue to shape the region’s identity and communal life (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Importance of intangible cultural heritage elements.

3.4. Contribution to Tourism and Economic Development

The survey explored the potential of cultural heritage elements to contribute to the tourism and economic development of the area.

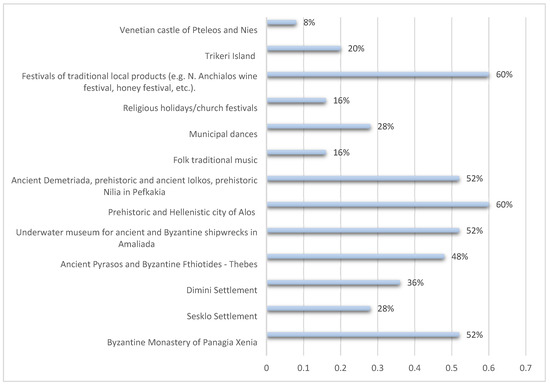

The respondents identified the Prehistoric and Hellenistic city of Alos (60%) and festivals involving traditional local products (60%) as the top contributors to tourism and economic development (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Contribution of cultural heritage to tourism and economic development.

3.5. Accessibility and Infrastructure Evaluation

Accessibility and infrastructure are critical factors in enhancing the visitor experience and integrating cultural heritage into everyday life.

Accessibility Ratings: The accessibility of archeological sites and cultural places received mixed reviews, with 52% rating accessibility as medium and 32% as poor. Only 16% of respondents considered accessibility to be good, indicating a need for infrastructural improvements (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Accessibility ratings of cultural heritage sites.

Infrastructure-related Challenges: The most pressing infrastructure issues identified were related to the road network (48%) and public transport (68%). Furthermore, the availability of information/service centers (64%) was highlighted as a significant gap, suggesting that improved services and infrastructure are necessary to fully exploit the region’s cultural heritage potential (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Key infrastructure-related issues for cultural heritage sites.

3.6. Evaluation of Proposed Projects

The surveyed participants were also asked to evaluate the proposed projects and their potential impact on the region’s cultural, tourism, and economic landscape.

Endorsement for Sea Interconnections: An overwhelming majority (92%) of respondents supported the introduction of sea interconnections among archeological sites via public sea transport or daily cultural cruises. This strong endorsement suggests that stakeholders recognize the significant value in integrating maritime transport into the cultural heritage strategy (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Endorsement of sea interconnection projects.

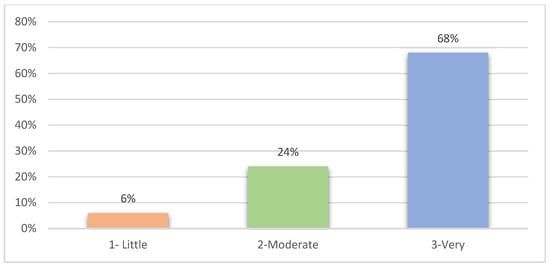

Integration into Everyday Life: Projects designed to integrate cultural heritage into daily life received strong support. The proposal for the creation of an archeological/cultural park in Pefkakia with a high-tech Exhibition Pavilion garnered an 80% approval rating, while an open-air theater project received support from 68% of respondents. These findings indicate that there is considerable interest in creating spaces that blend cultural heritage with community life (Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 13.

Support for cultural integration projects: high-tech exhibition pavilion.

Figure 14.

Support for cultural integration projects: an open-air theater.

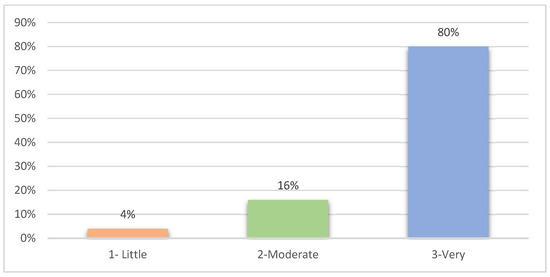

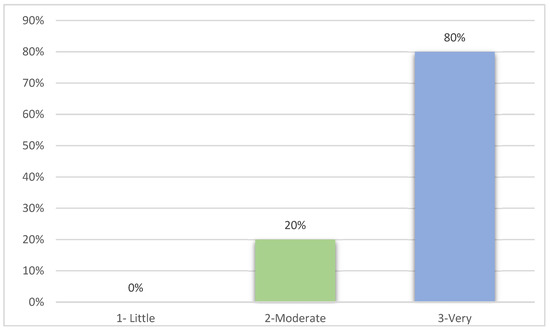

Social Participation and Strategic Planning: There was significant support for initiatives promoting social participation in cultural heritage management. Specifically, 80% of respondents supported the creation of a social network for monitoring cultural heritage projects and actions. Similarly, 80% endorsed the development of a strategic plan for cultural heritage based on participatory approaches and bottom–up proposals. These responses highlight the community’s desire for a more inclusive and democratic approach to heritage management (Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Figure 15.

Support for social participation.

Figure 16.

Support for strategic planning.

4. Discussion

Both the strategic planning and the participative social management of MCH in the West Pagasetic Gulf offer significant insights into the broader challenges and opportunities related to managing dispersed cultural heritage sites. In this framework, the research presented in this paper emphasizes the importance of integrating local communities into management and decision-making processes, enhancing the sustainability and economic potential of cultural heritage sites.

Firstly, our research highlights the significance of involving local communities in the management of MCH. Protecting and developing these areas is as much a primary concern for local communities as it is for indigenous groups [27,28]. It is essential to include local populations in the planning and decision-making processes related to the use and conservation of marine environments [29,30,31,32]. Excluding these communities from such processes erodes their trust and may result in opposition to conservation initiatives [33].

Thus, the creation of a socio-cultural network in the West Pagasetic Gulf facilitated active stakeholder participation and collaboration, which proved essential for developing context-sensitive management strategies. This approach fostered a sense of ownership and responsibility among local stakeholders, which is crucial for the sustainability of heritage management practices. Additionally, the establishment of a participatory lab enabled stakeholders to engage directly in the evaluation process, ensuring that the strategies developed were aligned with local needs and priorities.

It is important to clarify that this was the first stage of consultation, which was designed to gather input and foster dialog among key stakeholders. The participatory workshops and socio-cultural network described in this study primarily served as platforms for consultation, aligning with the initial goals of identifying shared aspirations and the challenges associated with managing MCH. However, consultation alone does not equate to active participation in decision-making processes, which require deeper institutional commitment and collaborative governance structures. Future phases of this research envision a progression from consultation to decision-making frameworks by engaging a broader spectrum of stakeholders and embedding participatory governance mechanisms within institutional practices.

This research primarily focused on gathering data from local officials, cultural heritage experts, and tourism professionals. This choice was driven by the need to establish a baseline for strategic planning and management of cultural heritage. However, it is acknowledged that incorporating broader societal groups, such as fishers, farmers, and others who may potentially be affected by development initiatives, is essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the region’s dynamics. The opinions of these professional groups was mainly approached through interviews. In future phases of this research, we plan to expand the scope of stakeholder engagement through participative workshops using questionnaires and focus groups to further explore the views and interests of these social actors. Such an approach will ensure a more holistic management strategy for cultural heritage and tourism projects, considering their compatibility with existing economic activities. This could involve creating platforms where local communities, professionals, and policymakers collaboratively define priorities and oversee project implementation. Such an evolution would ensure that stakeholders are not only heard but also empowered to influence decisions directly, thereby fostering a more inclusive and democratic approach to heritage management.

Our research findings highlight the potential of the socio-cultural network and Community of Practice to serve as critical vehicles for achieving this transition over time. Secondly, this research highlights the benefits of employing strategic terrestrial and maritime planning, combined with the development of cultural clusters and networks. By linking dispersed cultural sites into integrated clusters through thematic routes and connections, the region can enhance the visibility and accessibility of these heritage assets, thereby promoting tourism and economic development. This network approach not only attracts more visitors but also fosters a deeper connection between local communities and their cultural heritage, reinforcing cultural identity and social cohesion. Additionally, it integrates cultural heritage into the everyday lives of residents, further strengthening the cultural fabric of the community.

The participative procedure revealed that there are no conflicts among the previously mentioned stakeholders regarding the development of a cultural heritage park. This thematic park seems to be a part of a shared vision for handling the economic recession of the area, caused by the recent catastrophic floods in the region of Thessaly (which occurred in 2020 and 2023).

Thirdly, the adoption of smart solutions and soft projects, including digital platforms and cultural events, greatly amplifies the potential for managing heritage sustainably. These innovations can make cultural sites more visible and accessible, attracting a diverse audience and fostering cultural tourism. By utilizing technology and creative approaches, heritage managers can create immersive and interactive experiences that attract both visitors and locals.

The strategic initiatives outlined in this research are focused on developing cultural clusters, improving infrastructure, and fostering local community involvement through participatory governance, and are poised to significantly drive tourism growth in the West Pagasetic Gulf and Volos. By establishing a network of connected cultural sites, the region can offer a more integrated experience for visitors, likely increasing both the number of tourists and the duration of their stays. Additionally, the adoption of smart solutions, including digital platforms and maritime public transportation, will further enhance the region’s attractiveness by improving accessibility and offering innovative ways for tourists to engage with its rich cultural heritage.

The intention of the research project case study was indeed to promote the recognition of heritage elements to activate cultural tourism. This is acknowledged as a major potential (part of the territorial capital) benefit of the study area, and a major demand of the local society (almost all the stakeholders) and the local authorities. In 2020 and 2023, the district of West Pagasetic Gulf suffered from major floods due to cyclones. The local economy was hit hard, and it needs boosting, according to all stakeholders, including professional associations, inhabitants, local authorities, and the central state. Therefore, recognizing and promoting the area’s significant cultural heritage elements and the enhancement of its cultural identity have great potential for developing cultural tourism.

In addition to economic benefits, these strategies are anticipated to foster social convergence in the region. The inclusive approach to heritage management, which involves local communities in decision-making and promotes cultural heritage as a shared asset, is likely to strengthen social cohesion and build a stronger sense of collective identity among residents. As community members become more engaged in preserving and promoting their cultural heritage, there is a greater opportunity for social interactions and collaborations, which can lead to increased social capital and community resilience.

For the city of Volos, as a central hub of the West Pagasetic Gulf, the revitalization of its surrounding cultural heritage sites is expected to complement its existing urban attractions, thereby positioning the city of Volos as a gateway to the region’s rich historical landscape. This not only boosts the city’s profile as a cultural tourism destination but also stimulates local businesses and services that cater to an influx of visitors. Overall, the combined focus on tourism development and social convergence is expected to create a virtuous cycle of economic growth and social well-being, reinforcing the region’s cultural identity and contributing to its long-term sustainability.

5. Conclusions

As mentioned in the Introduction, the case study analysis presented in this paper belongs to a broader project entitled “Developing an Observation Network for Maritime Cultural Heritage (MCH) in Greece” [1]. This project developed a typology on how to embed and utilize MCH in two different territorial contexts in the country, i.e., the remote island context of the South Aegean Sea and the land–sea context of the Pagasetic Gulf in mainland Magnesia (Region of Thessaly).

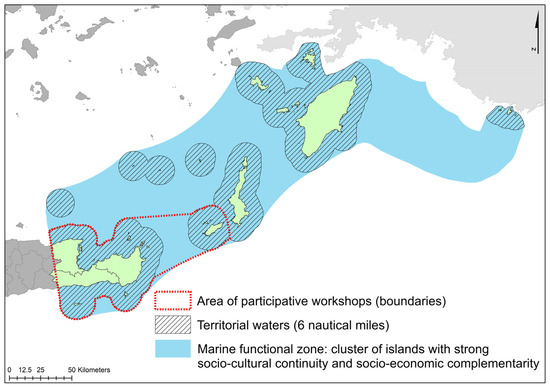

In the context of the islands (a cluster of islands in the South Aegean region, see Figure 17 and Figure 18 below), after a comprehensive analysis of the broader area and identification of “socio-culturally significant areas” through participatory workshops and PPGIS surveys, it was concluded that the Greek island space should be organized into “marine functional zones”. These zones would consist of island clusters that are socio-economically complementary and culturally continuous [1]. To make this concept operational and enhance “soft power” factors from a geopolitical standpoint, especially given the transboundary nature of the islands, a new management and funding model was proposed. This model introduces a novel type of investment, referred to as “integrated maritime investments” (IMI), aimed at fostering “maritime cohesion” [34]. This concept is analogous to the “territorial integrated investments” (ITI) tool, an effective instrument within the Cohesion Policy [35], which is designed to streamline the execution of territorial strategies requiring multi-source funding while promoting a more localized approach to policymaking [36]. In this context, funding could come from the Cohesion Policy, national island policies, and sectoral sources linked to the blue economy, tourism, culture, and defense.

Figure 17.

Clustering of islands in the Southern Aegean Sea, to increase connectivity and functionality in the marine space. Source: HERSEA HFRI project [1].

Figure 18.

Marine functional zone and cluster of islands in the Southern Aegean Sea. Source: HERSEA HFRI project [1].

The project offers policy recommendations on integrating cultural values and heritage into Maritime Spatial Planning, highlighting how culture—both tangible and intangible—can enhance Greece’s soft power. Greece’s islands, due to their strategic location between Europe and Asia, can play a key role in addressing regional challenges like geopolitical tensions, economic crises, and migration. By strengthening their economic, cultural, and diplomatic connections, Greece’s islands could become central in managing Eastern Mediterranean issues, particularly through frameworks like the EU’s Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP).

Key closing argument of the project is that Greece’s island regions, especially in the Aegean, should be viewed not just as territorial units but as interconnected hubs that can foster regional cooperation. These islands, with their rich history and strategic importance, are underutilized assets that could contribute to both Greece’s and Europe’s stability and security. The authors emphasize the urgency of recognizing their role in modern geopolitical dynamics, advocating for the concept of “soft geopolitical power” to enhance both Greek and European influence in the region.

As for the case study of the Pagasetic Gulf, which has been thoroughly presented in this article, the focus was on the creation of a network of cultural heritage sites (the opposite of a series of single, unconnected, and segregated heritage sites) located either on the coast or being underwater, to brand the area of West Pagasetic and reinforce cultural tourism development. This network approach not only draws more visitors but also strengthens the bonds between local communities and their cultural heritage, facilitating the enhancement of cultural identity and the promotion of social cohesion. This clustering of maritime heritage sites may also be implemented by the Region of Thessaly, using the tool of “integrated territorial investments” (ITI).

The project has also established a Community of Practice (CoP) focused on integrating maritime cultural heritage (MCH) into maritime spatial planning (MSP) in Greece, with plans to extend its reach to the broader Eastern Mediterranean. In the region, there are numerous policy drivers at the regional, sub-regional, and national levels promoting the adoption of MSP. Furthermore, MSP is actively being implemented through national Maritime Spatial Plans (MSPlans) alongside other national initiatives, strategies, and sectoral plans in both EU and non-EU countries. A wide range of research and pilot projects are supporting these efforts by providing data, tools, capacity-building, community engagement, best practices, and knowledge.

Given the existing policy framework and the increasing political commitment to MSP collaboration, there is a growing interest in incorporating maritime/underwater cultural heritage (MCH) into MSP. To facilitate this, the HERSEA project is uniting experts in the field—such as planners and maritime archeologists—as an MCH Community of Practice (CoP). Initially focused on Greece, the MCH-CoP will eventually expand to the wider Eastern Mediterranean while remaining inclusive of experts and observers from the entire Mediterranean region.

A key focus of the CoP will be on underwater cultural heritage (UCH), particularly its potential contribution to the blue economy and its role in driving smart specialization strategies at the regional level [37]. To this end, an informal UCH-CoP is being created within the HERSEA project (www.her-sea.eu (accessed on 23 December 2024)), which will enable voluntary exchanges of experiences and technical expertise related to UCH. This network will connect and showcase current, past, and future projects and initiatives, providing a platform for sharing knowledge and fostering collaboration among practitioners and stakeholders.

The UCH-CoP will also serve as a repository of best practices for integrating UCH into MSP and its potential contributions to the blue economy. By ensuring a consistent approach to UCH definition and implementation, the CoP will strengthen cooperation across regions committed to the conservation of MCH and its integration into MSP and the blue economy.

In conclusion, the project has made a meaningful social and political impact, and its ideas are likely to evolve and gain momentum through the continued work of the established Community of Practice that will be facilitated by the HERSEA website and discussion forum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-A.G. and S.S.K.; methodology, S.S.K., A.-A.G., A.-R.V. and D.K.; software, A.-R.V.; formal analysis, A.-A.G., A.-R.V. and D.K.; investigation, A.-A.G., A.-R.V. and D.K.; resources, A.-A.G., A.-R.V. and D.K.; data curation, A.-R.V. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-A.G., A.-R.V., S.S.K. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, A.-R.V. and S.S.K.; visualization, A.-R.V. and S.S.K.; supervision, A.-A.G. and S.S.K.; project administration, A.-A.G., S.S.K., A.-R.V. and D.K.; funding acquisition, S.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is based on the project entitled “Developing an observation network for MCH/UCH in Greece” (HER-SEA) funded by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation, grant number A.II. 44180/13.02.2022. S.S.K. is principal investigator of the Project. No funding has been received to cover the publication fees of this paper.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this research, since the humans involved were anonymous representatives of their organizations and, after being fully informed about the aim of the research, they provided their written consent to participate.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to warmly thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Developing an Observation Network for MCH/UCH in Greece; HER-SEA Project and Funded by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (ELIDEK), 2022–2024; Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences: Athens, Greece, 2023; Final Deliverables in Preparation; Available online: www.her-sea.eu (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Kyvelou, S.S.; Henocque, Y. How to Incorporate Underwater Cultural Heritage into Maritime Spatial Planning: Guidelines and Good Practices; European Commission, European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency Unit D.3—Sustainable Blue Economy: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; ISBN 978-92-95225-51-0. [Google Scholar]

- Barianaki, E.; Kyvelou, S.S.; Ierapetritis, D.G. How to Incorporate Cultural Values and Heritage in Maritime Spatial Planning: A Systematic Review. Heritage 2024, 7, 380–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banela, M.; Kyvelou, S.S.; Kitsiou, D. Mapping and Assessing Cultural Ecosystem Services to Inform Maritime Spatial Planning: A Systematic Review. Heritage 2024, 7, 697–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.E. Economic Values and Cultural Heritage Conservation: Assessing the Use of Stated Preference Techniques for Measuring Changes in Visitor Welfare. Ph.D. Thesis, Imperial College London, London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Khakzad, S.; Pieters, M.; Van Balen, K. Coastal cultural heritage: A resource to be included in integrated coastal zone management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 118, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, P.; Feener, R.M.; Ishikawa, N.; Mujah, I.; Irawani, M.; Hegyi, A.; Baranyai, K.; Majewski, J.; Horton, B. Challenges of Managing Maritime Cultural Heritage in Asia in the Face of Climate Change. Climate 2022, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, S. The Value and Valuation of Maritime Cultural Heritage. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2011, 18, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission; Directorate General for Fisheries and Maritime Affairs. MSPglobal: International Guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning; IOC/2021/MG/89; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; 148p. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, D. Theorizing the role of cultural products in cultural diplomacy from a Cultural Studies perspective. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2016, 22, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D. Cultural Diplomacy; Oxford Research Encyclopedias: International Studies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, H. Intangible Cultural Heritage and Soft Power—Exploring the Relationship. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2017, 12, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chitty, N.; Ji, L.; Rawnsley, G.D.; Hayden, C.; Simons, J. The Routledge Handbook of Soft Power; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, T. Heritage diplomacy. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention on the Protection of the UCH; UNESCO Digital Library: Paris, France, 2001; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000126065 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Hellenic Republic. Law 405/1976 on the Establishment of Ephorates of Antiquities and Other Provisions, Official Gazette 207/A/10-8-1976. Available online: https://www.anaconda.gr/gnwsiaki-basi/nomos-405-10-8-1976/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Hellenic Republic. Law 3028/2002 on the Protection of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage. Official Gazette of the Hellenic Republic, 153/A, 28-6-2002. Available online: https://search.et.gr/el/fek/?fekId=246815 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Hellenic Republic. Law 3409/2005 on Recreational Diving and Other Provisions; Official Gazette 273/A/4-11-2005; Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. Ministerial Decision “Classification of Wrecks as Cultural Properties”; Official Government Gazette 1701/Β/19-11-2003; Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. Law 4688/2020 on Special Forms of Tourism, Provisions Concerning Tourism Development and Other Provisions; Official Gazette A 101/24.5.2020; Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. Law 4858/2021 “On the Protection of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in General”; Official Gazette A 220/19.11.2021; Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kalamara, P. Different approaches to the protection and enhancement of underwater archaeological sites: Acquirements and Aspirations. Ann. Mar. Sci. 2022, 6, 021–033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Archive of Monuments. Available online: https://www.arxaiologikoktimatologio.gov.gr/en (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Calantropio, A.; Chiabrando, F. The Evolution of the Concept of Underwater Cultural Heritage in Europe: A Review of International Law, Policy, and Practice. Heritage 2023, 6, 7660–7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preka, K. The work of the Ephorate of Marine Antiquities during 2007–08 in the Northern Sporades, the Skandzoura Shipwreck: Research and Perspectives. In Proceedings of the Conference Highlighting the Underwater Archaeological Wealth of the Prefecture of Magnesia, Volos, Greece, 11 September 2010. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- BlueMed European Project. Available online: https://www.bluemed-initiative.eu/the-project/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Bishop, B.; Owen, J.; Wilson, L.; Eccles, T.; Chircop, A.; Fanning, L. How icebreaking governance interacts with Inuit rights and livelihoods in Nunavut: A policy review. Mar. Policy 2022, 137, 104957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.; Parsons, M.; Olawsky, K.; Kofod, F. The role of culture and traditional knowledge in climate change adaptation: Insights from East Kimberley, Australia. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Meur, P.; Mawyer, A. France and Oceanian Sovereignties. Oceania 2022, 92, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Ehara, H.; Thaman, R.; Veitayaki, J.; Yoshida, T.; Kobayashi, H. Traditional knowledge of medicinal plants on Gau Island, Fiji: Differences between sixteen villages with unique characteristics of cultural value. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, H.O.; Bender, M.G.; Oliveira, H.M.; Pereira, M.J.; Azeiteiro, U.M. Fishers’ knowledge on historical changes and conservation of Allis shad-Alosa alosa (Linnaeus, 1758) in Minho River, Iberian Peninsula. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 49, 102094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleson, K.L.; Barnes, M.; Brander, L.M.; Oliver, T.A.; van Beek, I.; Zafindrasilivonona, B.; van Beukering, P. Cultural bequest values for ecosystem service flows among indigenous fishers: A discrete choice experiment validated with mixed methods. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 114, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyvelou, S.S.; Ierapetritis, D.G.; Chiotinis, M. The Future of Fisheries Co-Management in the Context of the Sustainable Blue Economy and the Green Deal: There Is No Green without Blue. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyvelou, S.S.; Ierapetritis, D. Discussing and Analyzing “Maritime Cohesion” in MSP, to Achieve Sustainability in the Marine Realm. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy: A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations, Independent Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2009; Available online: https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2010-12/docl_17396_240404999.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Smanis, A.; Kyvelou, S. Establishment of the HERSEA Network and Community of Practice. DELIVERABLE N° D.2.4, Final Draft. 30 March 2024. Available online: https://her-sea.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/PU_DELIVERABLE-PU-D.2.4-MUCH-Network-and-CoP.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).