1. Introduction

In the context of the valuation of industrial heritage, old flour mills constitute a singular testimony to the relationship between humanity, technology, and the environment. In the region of Ciudad Rodrigo in the province of Salamanca, these spaces have played a fundamental role in the local economy for centuries. Currently, they are the subject of a transformation process that combines their conservation with the creation of a new cultural and tourist dynamic. The buildings were originally constructed for the purpose of grain milling and other industrial activities. They have since become a pivotal resource for the sustainable development of rural areas and the diversification of the regional economy.

The rehabilitation and conservation of this heritage has enabled the preservation of its historical and architectural value, while simultaneously facilitating its adaptation to new uses that enrich the cultural space surrounding the town of Ciudad Rodrigo. The rehabilitated mills have been transformed into a variety of facilities, including interpretation centres, museums, and leisure facilities. These have been upgraded and contribute to the creation of innovative and intelligent tourist experiences that value the history and identity of the territory and the environment in which they are located. This transformation also promotes sustainable tourism, which is in line with global strategies to minimise environmental impact and encourage the involvement of local communities in the use of their heritage.

This article examines the role of these former industrial spaces, including flour mills, fulling mills, and some other types of mills, in the Salamanca region of Ciudad Rodrigo. Through a series of tourist routes, the region is promoting rural development and redefining the cultural landscape of the area. The impact of these initiatives is analysed from an integral perspective, addressing economic, social, and environmental aspects, with an emphasis on sustainability and the role of tourism as an engine of transformation. Furthermore, this article reflects on the challenges and opportunities that arise when integrating these spaces into local development strategies, reaffirming their importance as living elements of heritage.

2. Literature Review: Regulatory Framework and Main Industrial Heritage Organisations

Industrial heritage, the most recent of all cultural heritages, is constituted by a set of buildings, machinery, and elements used in relatively recent times. In contrast to other forms of heritage, it is not always regarded with the same degree of historical or artistic significance by the general public, as it does not necessarily align with the conventional notion of the ’old’. Nevertheless, the analysis of industrial heritage has been comprehensive and interdisciplinary, encompassing fields such as art history, architecture, anthropology, and geography, which have contributed to its expansion and enrichment beyond the traditional boundaries of these disciplines [

1].

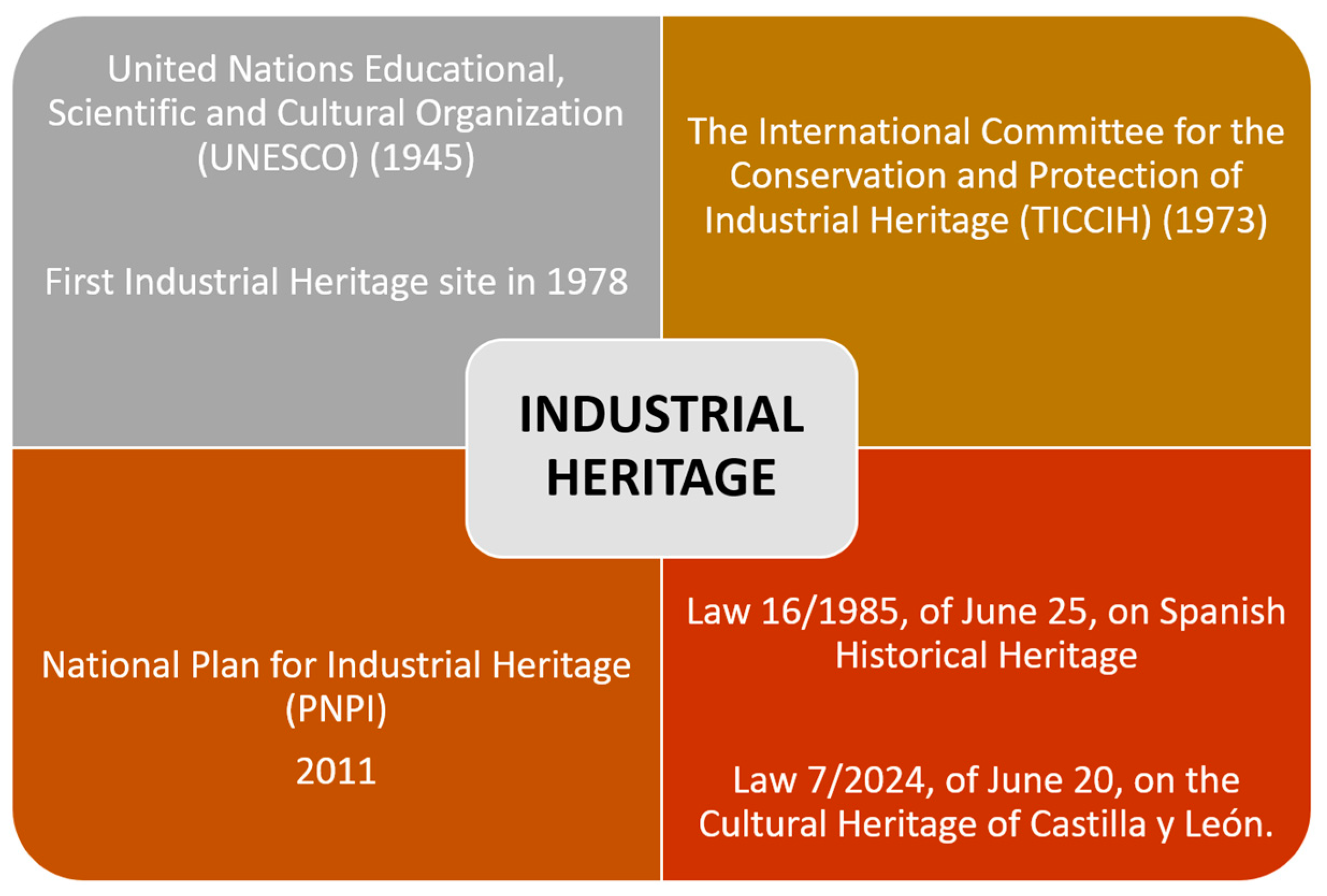

Despite its relative youth as a concept, it is of great interest to organisations, associations, and administrations, which are working to achieve greater protection, conservation, interpretation, dissemination, and enhancement of its value. It is pertinent to highlight some of these at different scales and territorial spheres of action (see

Figure 1). At the international level, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Committee for the Conservation and Defence of Industrial Heritage (TICCIH) are of particular significance. At the national level, the National Plan for Industrial Heritage and Law 16/1985 of 25 June 1985 on Spanish Historical Heritage are noteworthy. In the context of our study, which focuses on the region of Castilla y León (Spain), we will also mention Law 7/2024 of 20 June on the cultural heritage of Castilla y León. Both the state Law 16/1985 and the regional Law 7/2024, as previously mentioned, refer to cultural heritage. However, there are no specific laws on industrial heritage. Industrial heritage is an integral part of cultural heritage.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) was established in 1945 and currently lists more than 1200 World Heritage Sites in over 160 countries. Nevertheless, it was not until 1978 that an industrial heritage site was added to the list: the Royal Wieliczka Salt Mine in Poland. This declaration constituted a significant turning point in the appreciation of this type of heritage, leading to its wider recognition and the subsequent addition of new sites to the list, including the Royal Salt Mine of Arc-et-Senans (France, 1982), the 19th-century workers’ village of Crespi d’Adda (Italy), and the 19th-century saltworks of Wieliczka and Bochnia (Poland). In 1995, the Derwent Valley Mills in the UK were designated as a World Heritage Site, encompassing 18th- and 19th-century cotton spinning mills. Spain’s first-century AD gold mines at Las Médulas were inscribed in 1997, showcasing significant evidence of their historical exploitation. In the case of Spain, the first century AD gold mines of Las Médulas (1997) with important traces of their exploitation in Roman times, the Vizcaya metal architecture ferry bridge (see

Figure 2) built in the Industrial Revolution (2006), and the Heritage of Mercury, Almadén (2012), with the largest mercury mine in the world, together with Idria in Slovenia, were designated as World Heritage Sites. The next examples illustrate the diverse range of industrial heritage sites inscribed on the World Heritage List [

2], which has expanded over time. They demonstrate UNESCO’s ongoing commitment to this category of heritage, encompassing not only sites associated with the Industrial Revolution but also those from all historical periods.

In particular, the International Committee for the Conservation and Defence of Industrial Heritage (TICCIH) has been responsible for the protection of industrial heritage on a global scale since 1973. Additionally, it provides advisory services to the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). At its meeting held in Moscow on 17 July 2003, the organisation established the definition of industrial heritage as set forth in the Nizhny Tagil Charter on Industrial Heritage [

3]. This definition encompasses the remains of industrial culture that possess historical, technological, social, architectural, or scientific value, which is a legacy that spans the entire period of the Industrial Revolution, from the late 18th century to the present day. Such remains encompass a multitude of structures and systems, including factories, machinery, mines, warehouses, transport networks, and energy infrastructure. Additionally, they include spaces of social coexistence linked to industry, such as dwellings, religious temples, and educational institutions. Furthermore, the intangible elements that constitute this heritage, such as ways of life, customs, and traditions, are also acknowledged.

The definition proposed by TICCIH is essentially identical to that set forth in the National Plan for Industrial Heritage (PNPI) in Spain [

4], which was approved in 2011 and updated in a previous plan that was in force between 2000 and 2010. The plan defines industrial heritage as the set of material goods, real estate, and social relations generated by activities such as extraction, transformation, transport, distribution, and management derived from the industrial economic model that emerged from the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. In order to fully comprehend this ensemble, it is essential to consider it within a global framework that encompasses the environment in which it is situated, the industrial relations that shaped it, its architectural structures, the techniques employed in its processes, the archives produced as a result of its activities, and the associated symbolic practices.

At the national level, legislation pertaining to heritage is in place, notably Law 16/1985 of 25 June 1985 on Spanish Historical Heritage [

5]. While industrial heritage is not explicitly referenced, it is nevertheless encompassed by this legislation, as it falls within the scope of heritage delineated in Article 1.2:

“Spain’s Historical Heritage includes movable and immovable property of artistic, historical, palaeontological, archaeological, ethnographic, scientific or technical interest. It also includes documentary and bibliographical heritage, archaeological sites and areas, as well as natural sites, gardens and parks of artistic, historical or anthropological value.”

At last, we encounter Law 7/2024 of 20 June on the cultural heritage of Castilla y León [

6], which makes reference to industrial heritage throughout the text. Point II of the explanatory memorandum of this law elucidates the necessity to incorporate into the regulations of this community the evolution towards new theoretical approaches set out in international and national texts in which industrial heritage is included. Article 12.1 indicates the assets that make up the cultural heritage of Castilla y León:

“The Cultural Heritage of Castilla y León is made up of tangible and intangible assets with historical, artistic, architectural, archaeological, landscape, ethnological, industrial, scientific and technical values, including traditional and popular architecture, as well as palaeontological values related to the history of mankind. It also includes documentary, bibliographic and linguistic heritage.”

This legislation serves to reinforce the importance of industrial heritage and maintains the highest level of protection for Sites of Cultural Interest (BIC) by incorporating a new figure of protection within the heritage areas, which are defined as industrial ensembles. The term "industrial ensemble" is defined in article 20.1.f as "the set of assets linked to production, extraction, transformation, transport and distribution activities that must be preserved due to their technical, scientific or historical value".

3. Theoretical Framework: Industrial Heritage and Its Relation to Tourism

The concept of industrial heritage, defined as the collective set of infrastructures, machinery, and architectural features associated with past productive activities, has emerged as a major tourist and cultural attraction [

7]. These spaces, restored and adapted, provide visitors with an understanding of the historical processes of industrialisation and their impact on society and the economy. The promotion of industrial tourism allows regions to preserve their cultural heritage while simultaneously creating new opportunities for economic and social development in the wake of deindustrialisation, a process that has affected numerous territories [

8]. The consequence of this is that the resulting vacuums sometimes become degraded spaces, and in other cases they are rehabilitated and integrated into the landscape, thereby facilitating the revitalisation of tourism. The revitalisation of these spaces promotes sustainability, as it avoids the demolition of historic buildings and transforms them into tourist attractions that serve to enhance the local identity of the towns in which they are located. On other occasions, the reuse of these spaces allows the renovation of industrial areas, transforming them into residential or commercial spaces, making their surroundings more dynamic, beautifying the spaces and, consequently, revaluing the land [

9,

10].

The interconnection between these two concepts is elucidated in the publication

Tourism and Industrial Heritage [

11], which elucidates the significance of industrial heritage for the advancement of tourism and local economic growth. This is achieved through the enhancement of industrial heritage elements, including buildings, machinery, transport systems, and so forth. This work presents a variety of case studies from Europe and America, illustrating the diverse forms that industrial heritage can take. These include textile enclaves, salt mines, sugar mills, industrial villages, and railways, among other examples. Such developments are supported by the necessity for programmes and plans designed to stimulate tourism, thereby enhancing the value of this heritage, which is frequently overlooked and segregated from the more traditional cultural heritage of castles, palaces, churches, monasteries, etc.

A substantial body of research exists that elucidates the interrelationship between industrial heritage and tourism. The number of case studies has increased, with examples drawn from urban and rural contexts worldwide. The interest in industrial heritage tourism has increased in recent years and is becoming a well-established typology of cultural tourism. This is due to the growing appreciation of old productive infrastructures and their social and economic history. These sites offer a distinctive experience, allowing visitors to explore the technological evolution and working conditions of bygone eras. This type of tourism not only preserves heritage assets but also stimulates the economic development of regions that have ceased to be active industrial centres and have become disused spaces.

The development of tourism initiatives linked to industrial heritage encompasses a diverse array of typologies [

12], reflecting the multitude of industrial activities that have emerged over centuries. The specific activity that is most prominent in any given territory depends on the historical development of the area. For instance, in some cases, the focus is on electricity generation [

13], as evidenced by the numerous power stations that were constructed during the Industrial Revolution. In other instances, the emphasis is on sugar production [

14], as exemplified by the numerous mills that were built to process the sugar cane that was grown in the region. Similarly, tobacco factories [

15] and navigation channels [

16,

17,

18] also stand out as prominent features of many industrial heritage sites. Mines, salt mines, textile factories, and railway infrastructure also feature prominently in many cases.

The United Kingdom and central Europe were the epicentres of industrialisation. Consequently, there has been considerable interest in the reconversion of industrial spaces into more attractive areas to live in in these regions. This has involved the modernisation of cities through the occupation of old, disused, and even ruined factory buildings with museums, exhibition halls, art galleries, and other cultural facilities. In addition, many of these buildings have been converted into libraries, supermarkets, and restaurants. In the case of Wales, which was the epicentre of industrial activity during the 19th and 20th centuries, tourist attractions were created by taking advantage of the buildings that were constructed around the mines, mills, railways, and so forth [

19]. It is also noteworthy to mention the Belgian case, which was among the first countries to embark on the industrial revolution and has a rich industrial history [

20]. Urban regeneration projects have been undertaken in factories situated in city centres, which possess a rich and diverse industrial heritage. The Walloon region is characterised by a legacy of heavy industry, while the textile industry is a prominent feature of Flanders. Nevertheless, the majority of the country’s industrial heritage is concentrated in the railway and mining sectors.

The transformation of mining heritage into a tourist destination is a particularly illustrative example of this phenomenon [

21]. The principal initiatives undertaken have been the conversion of facilities and constructions into museums and the transformation of their surrounding areas into parks. The objective was to rectify the economic and environmental damage to the surrounding area, which had deteriorated due to the activity being carried out, and to establish a significant role in the identity of the local inhabitants. Two case studies merit particular attention as illustrative examples of this phenomenon in Chile. These are the Arauco Gulf [

22] and the mining area of Lota [

23].

In the context of railway heritage, a multitude of proposals have been put forth, and the initiatives are highly promising for the advancement of tourism development [

24]. In Europe, the Semmering railway line in Austria, which has been designated a World Heritage Site since 1998, is a notable example. It features significant engineering works, including tunnels and viaducts, and is situated in an area of considerable natural value. The track remains operational and serves as a tourist attraction, with visitors travelling the approximately 40 kilometres of the Austrian Southern Railway. However, a considerable number of the original railway tracks are no longer in use and are in a state of disrepair. The objective of restoring disused railway tracks is to preserve their historical and cultural value, transforming them into useful and attractive resources. This has been successfully achieved in a number of cases in Spain, including the Strawberry Train, the Sóller Railway, the Campos de Castilla Train, and the Expreso de La Robla. This process typically entails the conversion of disused railway lines into leisure routes, thereby reviving the railway past while simultaneously promoting tourism and sustainable development. In some instances, these initiatives have been successfully implemented, as evidenced by the Trem da Vale in Brazil [

25]. In other cases, revitalisation initiatives have been undertaken, such as the proposal to revitalise the Valladolid-Ariza line in Spain, specifically in the Ribera del Duero section in Valladolid, with the wine train [

26].

The present study focuses on the hydraulic mills used for the production of energy, which allowed for the grinding of cereals—a crop par excellence in Castile—but which were also widely distributed throughout the peninsular territory. Flour mills were distributed throughout the territory, as their activity was integral to the daily lives of the population. Some works that focus on the industrial activity for which they were conceived, namely the milling of grain, are particularly noteworthy in areas such as La Serena in Extremadura [

27], the provinces of Córdoba [

28] and Granada [

29,

30], along the Tajo river [

31], in the Cádiz mountains [

32], or in the Duero, specifically in the province of Zamora [

33]. A considerable number of these structures have been abandoned and have disappeared, while many others have been restored and transformed into museum spaces, interpretation centres, multicultural enclosures for meetings and congresses, hotels, and rural houses [

34,

35,

36]. Also interesting are the works that aim to reconstruct artefacts, such as water and windmills, using 3D techniques and computer animation. These techniques are used both to understand the technical aspects of their operation and to disseminate information among people [

37]. This has resulted in the mills becoming a significant tourist resource, particularly in rural areas, although there are also mills in cities. A further potential use for these structures is to provide an alternative means of economic development, with a particular focus on tourism. This could be achieved through a variety of means, including the organisation of guided tours of the old installations and the creation of tourist routes, which would offer visitors insights into the construction and historical use of the mills.

4. Study Area: Ciudad Rodrigo Region

In 1985, the Junta de Castilla y León conducted a study with the objective of developing a commercialisation strategy for the autonomous community. This resulted in a proposal comprising a total of 79 comarcas distributed across the nine provinces (see

Table 1). Nevertheless, in 1991, only one comarca, El Bierzo in the province of León, was officially recognised by law [

38], resulting in the establishment of a Regional Council. Nevertheless, despite the absence of official recognition, this commercialisation has been employed in certain instances pertaining to the operational aspects of public services. In this regard, a network of county centres has been established, serving as the primary points of integration within the territory. These centres oversee the coordination of a range of activities, including educational, health, judicial, agricultural, commercial, and others.

With regard to the province of Salamanca, a total of 11 comarcas were established. The resulting administrative divisions were as follows: Vitigudino, Ciudad Rodrigo, La Armuña, Las Villas, Torres de Peñaranda and Las Guareñas, Tierras de Ledesma, Comarca de Guijuelo, Tierra de Alba, Sierra de Béjar, Sierra de Francia, and Campo de Salamanca.

The study area of this work is the current district of Ciudad Rodrigo, which comprises a total of 53 municipalities (see

Figure 3). The district is situated in the south-western extremity of the province of Salamanca, with its boundaries defined by the Sierra de Gata to the south and the Arribes del Duero to the west, which marks the frontier with Portugal. The landscape is characterised by the ’Campo Charro’, comprising extensive pastures of holm oaks and pastureland used for livestock farming. The principal river is the Águeda, a tributary of the Duero. It flows through the town of Ciudad Rodrigo. The hydrographic basin is comprised of a vast network of rivers, including the Badillo, Roladrón, and Turones, as well as numerous streams, such as La Granja, La Ligiosa, and del Muerto. Additionally, the Ahijal irrigation channel plays a significant role in the region’s hydrological system. The aforementioned watercourses have facilitated the establishment of a significant milling industry, with a network of flour and fulling mills capitalising on the presence of these watercourses and the region’s topographical characteristics. As stated in the Diccionario Geográfico–estadístico–histórico de España y sus posesiones de ultramar, vol. I (1845), the entry on the Águeda river in this dictionary states the following:

“AGUEDA: river in the province of Salamanca: it rises from the waters which flow to the north from the foothills of the Sierra de Gata and mainly in the passes of Valverde and the high mountain range of Jalama, on the borders of Castilla la Vieja and Estremadura (...) The main use of this river, as Ponz says, and whose pure and crystalline waters have been the subject of sonnets and compositions by many famous poets, is to move some fulling mills and many mills, of golden sands, as Ponz says, and whose pure and crystalline waters have been the subject of sonnets and compositions by many famous poets, consists of providing movement to some fulling mills and many flour mills, some of them notable for the fall of the waters between the rocks, such as the mill of the Devil, among others: This service is easily provided, due to its steep slope and the abundance of slatey stone of which its steep banks are made up, which prevent the waters from Ciudad-Rodrigo onwards from being used for irrigation, which up to there have been used to fertilise a multitude of linares, patatales and all kinds of vegetables (…)”. [

39].

Milling activities were of great importance in the plains of Castile, where cereal cultivation played a significant role. These activities have left behind tangible evidence in the form of industrial heritage elements, some of which have become tourist attractions and a source of revitalisation for the rural environment.

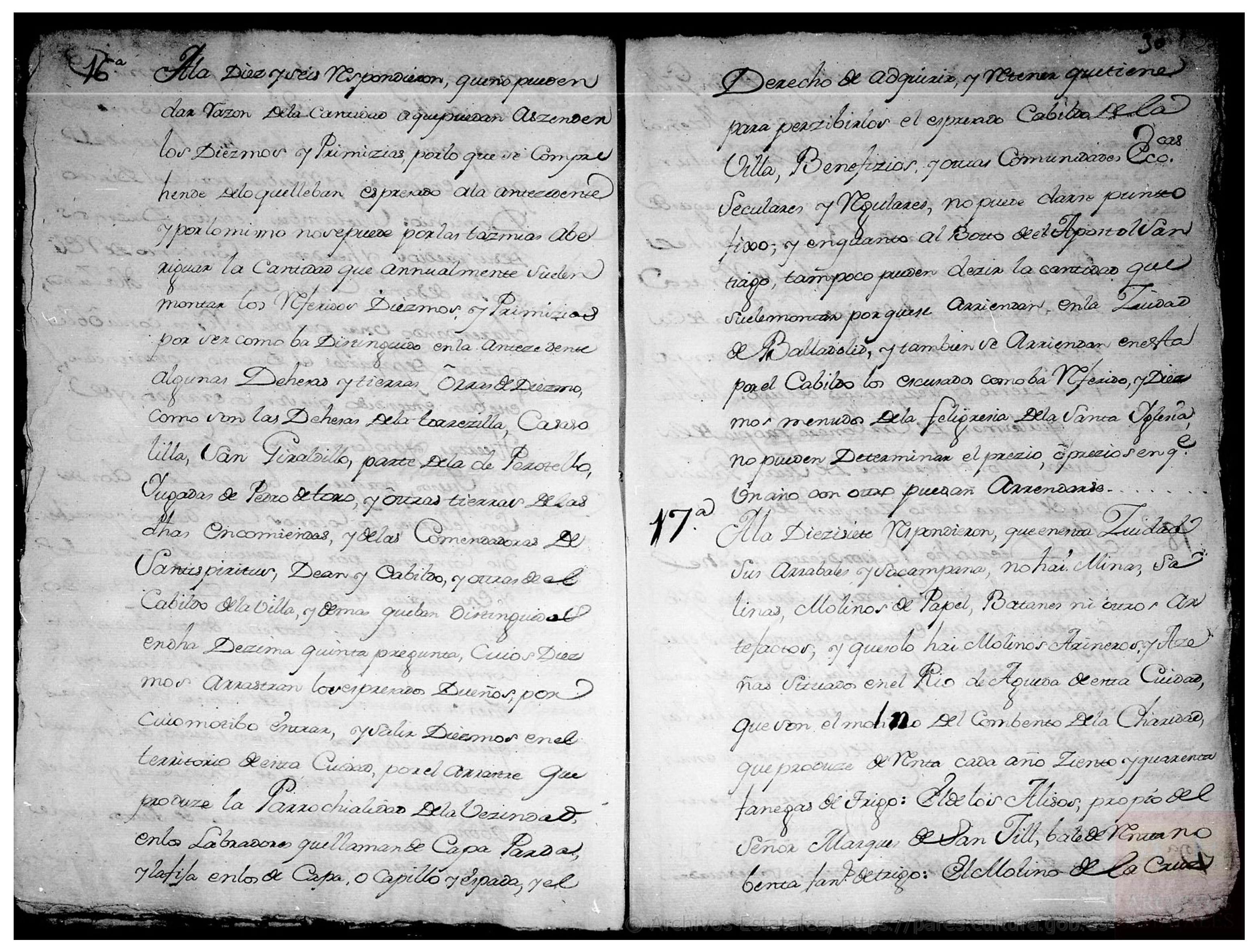

The present work is based on the Cadastre of the Marqués de la Ensenada, a cadastre drawn up in the Crown of Castile between 1749 and 1756 with the aim of comprehensively documenting the assets of all individuals. The purpose of this documentation was to serve as a tool for calculating a tax that would simplify the provincial revenues into a single tax. To facilitate this calculation, the Crown initiated a comprehensive investigation into the assets, income, and obligations of all residents, irrespective of their secular or noble status. Notably, this investigation also encompassed the registration of the ecclesiastical estate for the first time. The inquiry proved to be a success, yielding a substantial body of documentation amounting to over 80,000 thick handwritten bundles from the Crown of Castile. However, the fiscal transformation was not implemented, thereby falling short of the fiscal equity and justice objectives pursued by the Marqués de la Ensenada [

40,

41,

42].

The methodology employed in this study entails the consultation of the Cadastre of Ensenada, specifically the General Answers of the 53 municipalities constituting the study area, which are available on the website of the Ministry of Culture. The utilisation of this geohistorical source has facilitated the extraction of information pertaining to the existence of mills in the mid-18th century. In addition to this documentation, the summary statements of the letter E of the province were consulted, where the wealth or usefulness of all the mills by typology was collected. With both pieces of information, an analysis was proceeded with to see the number, condition, and utility of the mills in the study area. Concomitant with this documentation analysis phase, fieldwork in the study area enabled the assessment of the condition of the extant mills located in Ciudad Rodrigo. Concurrently, it was ascertained that those situated in adjacent areas have either disappeared or are in a state of significant abandonment and dilapidation.

Once we had these data, we went on to analyse the mills that are currently preserved in the study area, highlighting that, with the exception of Ciudad Rodrigo, the rest have not taken measures to systematically recover these artefacts from these spaces. These data were obtained from official local government sources, such as the General Urban Development Plans.

5. Results

The results of this research show two obvious elements. The first has to do with the historical analysis of the mills in the study area, in addition to the number of industrial artefacts and their use. Secondly, it sheds light on what has happened in the area in terms of the protection of the industrial heritage, and its attempts at revitalisation: with proposals such as the routes, their repercussions, as well as the opening of new lines of research and implementation, such as the Smart Tourism Destinations, which could alleviate such deficiencies, the latter being one avenue on which we are working.

5.1. Historical Developments

In order to develop a methodological framework for our research, we have chosen to use the current municipalities and supplement them with data from former population centres that were previously located within them [

43]. This approach may alter the perception of the entities in question, but it will not affect our representation of the evolution of heritage and its transformation.

In light of the aforementioned considerations, it is evident that the Ensenada Cadastre, which has been preserved, provides evidence that in the mid-18th century, there were a considerable number of flour mills and other mills in the region under analysis. The data provided in the state of the letter E and the ’General Answers’ of the Ensenada Cadastre indicate that there were 149 mills in the region, with an estimated value of 46,055 reales de vellón (approximately 12.03% of the province of Salamanca). Additionally, there were six oil mills, which collectively yielded 7368 reales de vellón (20.81%), and four fulling mills, which produced a total of 543 reales de vellón (4.51%) [

44] (see

Table 2). The mills that have survived are located in Ciudad Rodrigo; the rest have either been destroyed or are no longer extant [

45].

A century ago, the data in the Diccionario Geográfico–estadístico–histórico de España y sus posesiones de ultramar and its overseas possessions, from the mid-19th century, compiled by Pascual Madoz, indicate a lower number of artefacts in many places. However, in others, as in the case of Alba de Yeltes, the number triples to six flour mills in a century. It is also pertinent to consider the developments in Ciudad Rodrigo, which, as the most significant urban centre, will be examined in depth, given that it has been one of the few municipalities capable of reinvigorating the region by adapting its heritage, although not so with those that were previously autonomous and are now within its municipal boundaries.

In the mid-18th century, the Cadastre of Ensenada indicates that the following mills were located in Ciudad Rodrigo (see

Figure 4):

“The mill of the Convento de la Charidad, which produces, each year, one hundred and forty fanegas of wheat; the mill of Los Alisos, belonging to the Marquis of San Jil, which produces ninety fanegas of wheat; the mill of La Cruz, belonging to the same Marquis of San Jil, produces one hundred and ten fanegas of wheat; The mill of the Muradal, belonging to Don Joachín Arias Pacheco, yields one hundred and twelve fanegas of wheat; the mill of Caraveo, belonging to the Marquis of Villacampo, yields one hundred and ten fanegas of wheat; and the mill of Carbonero, belonging to the widow, children and heirs of Juan Galache, yields one hundred fanegas of wheat per year” [

46].

Volume II of the Diccionario Geográfico–estadístico–histórico de España y sus posesiones de ultramar indicates that the Águeda river traverses Ciudad Rodrigo.

“Over which there is a magnificent bridge in this city, and they enter those different streams. They pass through different fords, from the valley to the Pizarral, there are those of Cantarranas, the one of the Alisos mills, the one of Puente, the one of Barragán, the one of Palomar, the one of Oro and the one of Carbonero”.

A century later, the number of mills remains similar, with only a single decrease in the number described, despite the absence of further information about them. The rationale for abandonment is attributed to the construction of the

Fábrica de la Concha factory adjacent to the city wall (see

Figure 5). This factory, distinguished by its quality and capacity for flour production, led to the gradual closure of the smaller mills along the Águeda river, compounded by the imposition of higher taxes.

5.2. Transformation into a Cultural and Leisure Space

Since the 20th century, we can see that these areas have been abandoned and forgotten. If we look at the official documentation of the local entities through the

’Planes Generales de Ordenación Urbana’, we can see that most of them have disappeared and there is not even a record of them in these localities. In other words, only a few of the mills along the Águeda river have been restored and transformed so that they can be visited today. Specifically, in Ciudad Rodrigo, where the public documentation dates from 2018 [

48], there are mills in need of improvement. One of them is the Rincón mill, which is described as having a rectangular floor plan measuring 14 by 10 square metres and is relatively well preserved despite being abandoned. The Caridad mill, on the other hand, is in need of integral protection, cleaning, conservation, and restoration. Others, such as the Caraveo mill, are in good condition, while the Moreta mill, dating from the end of the 19th century, is being restored and requires environmental protection.

This situation led to a rethinking of the use of these spaces, which were deteriorating and being lost. For this reason, policies have been put in place for their recovery, which have led, for example, to the transformation of the Fábrica de la Concha into a socio-cultural and accommodation space. On the other hand, thematic routes have been created to promote the dissemination of the heritage, such as the so-called Route of the Mills, which aims to recover and use these spaces by promoting outdoor activities linked to hiking. This route has been signposted by the Youth Volunteering Programme and goes from La Concha to the Carbonero mill, allowing us to see the Mariego bridge or the Las Chancas mill, which is in ruins. It should not be forgotten, however, that others, such as the mill of La Ceña, have disappeared completely, and even the mill of Marino Risueño disappeared with the construction of the motorway.

Recently, the Integral Strategic Plan of the Águeda river has been launched to integrate, revitalise, and restore the spaces of Ciudad Rodrigo, with the aim of adapting and conditioning a 28-kilometre route and connecting them at Sanjuanejo and

Molino de Carboneros. The central axis of this route will continue to be the mills and former industrial sites. The aim is to increase the tourist offer and to highlight the importance and environmental and economic benefits of this process of conversion of the area [

49].

Another site in which the recovery of an old mill has been achieved is the current Hotel Águeda, located in Ciudad Rodrigo (see

Figure 6). It is located on the banks of the river, surrounded by 14 hectares of woodland, in an area close to the city. The refurbishment of the hotel has made it possible to transform both the exterior and interior of this old industrial artefact into a space for leisure and relaxation while respecting its heritage. However, as we have already warned, these cases are almost exceptional among the mills in the area, as compared to those found and described in the mid-18th century; there is not much left of the rest, due to ruin or abandonment.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The conversion of industrial heritage into a tourist attraction in the Ciudad Rodrigo region poses both challenges and opportunities for sustainable rural development. This phenomenon has been observed in other regions, such as La Alpujarra de Granada in Spain [

50] furthermore, this process involves not only the conservation of the industrial remains but also their reinterpretation as cultural and tourist spaces that revitalise the local environment. Despite the progress made, there are still shortcomings and problems that limit the impact of these initiatives. Among the main challenges are the lack of investment in infrastructure, the scarce digitalisation of resources, and the need for a comprehensive strategy that combines industrial tourism with the demands of today’s tourists.

In this context, the concept of smart destinations emerges as a key solution to overcome these limitations [

51,

52,

53]. The implementation of advanced technologies could optimize the management of industrial heritage, improve the visitor experience, and ensure the economic, social, and environmental sustainability of the rural environment, which in this territory is in economic and social decline, with a significant loss of population, services, infrastructure, and economic activity. However, this requires a joint effort between public institutions, private companies, and local bodies to ensure a fair and beneficial development for all stakeholders.

The region of Ciudad Rodrigo has a valuable industrial heritage, with watermills and fulling mills linked to historical economic activities, as has been verified by consulting the historical documentation of the Ensenada Cadastre and by fieldwork carried out in the area. However, many of these elements are not adequately maintained or recognised, many have disappeared, and others are in a poor state of conservation, which makes it difficult to include them fully in the tourist circuit. However, there are other water mills that have been rehabilitated and have become an important endogenous development resource. In order to reverse the situation of a large part of this industrial heritage, it is essential to enhance its value through rehabilitation and musealisation processes that respect its authenticity and its link with the natural and cultural environment.

Tourist routes play a fundamental role in this process, acting as catalysts for endogenous development. By linking industrial resources with other local attractions, such as historical–artistic heritage or gastronomy, they promote economic diversification and the dynamisation of the territory. As well as attracting visitors, these routes create jobs and strengthen the cultural identity of rural communities. However, their success depends on proper planning that takes into account sustainability criteria and ensures the active participation of the local population. Examples of these proposals include works that highlight the industrial heritage and vernacular architecture, such as windmills in Andalusia [

54], the industrial heritage of the municipality of Madrid, directing the facilities towards cultural and tourist uses that allow tourist diversification [

55], or the case study of mining heritage in Castilla La Mancha with the creation of tourist routes taking advantage of the opening of an iron mine in the province of Cuenca and the enhancement of two traditional mining areas, such as the regions of Almadén and Puertollano, both in the province of Ciudad Real [

56].

Despite their heritage value, the mills in the district of Ciudad Rodrigo continue to be an underused resource in terms of tourism. Throughout the research and fieldwork carried out, it has become evident that a large number of these mills have disappeared, while the few that are still standing are underused in terms of their tourist and cultural potential. The lack of both public and private initiatives for their conservation and reuse has been a significant barrier. It is imperative that local administrations assume a more proactive role in the preservation of these assets, ensuring their maintenance and protection. Simultaneously, the involvement of private entities, capable of developing sustainable tourism initiatives that valorise these resources, should be fostered. Preserving the mills as historical testimonies is paramount; however, it is equally crucial to reimagine them as dynamic contributors to the socio-economic advancement of the region. The strategic implementation of heritage tourism has the potential to serve as a catalyst for economic growth, employment creation, and the revitalisation of local cultural identity. It is therefore imperative that comprehensive policies are adopted to ensure the preservation, promotion, and enhancement of these mills, acknowledging their role as an integral component of the cultural heritage of the district of Ciudad Rodrigo. By doing so, the foundations can be laid for a future where the mills are not only preserved but also appreciated and utilised as an active part of the landscape and heritage.

In conclusion, the transformation of the industrial heritage in the region of Ciudad Rodrigo into cultural and tourist spaces represents a strategic opportunity for the rural development of this territory. It is necessary to address current shortcomings by adopting innovative models, such as smart tourist destinations, and to strengthen the role of tourist routes as tools for territorial cohesion. It is also essential to raise awareness of the value of industrial heritage, promoting its conservation and use as a driver of economic and social development. Only through an integrated and sustainable approach will it be possible to consolidate the Ciudad Rodrigo region as a competitive tourist destination, while preserving its historical and cultural heritage for future generations.