Reconstructing an Individual’s Life History by Using Multi-Analytical Approach: The Case of Sofia Kaštelančić née di Prata

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

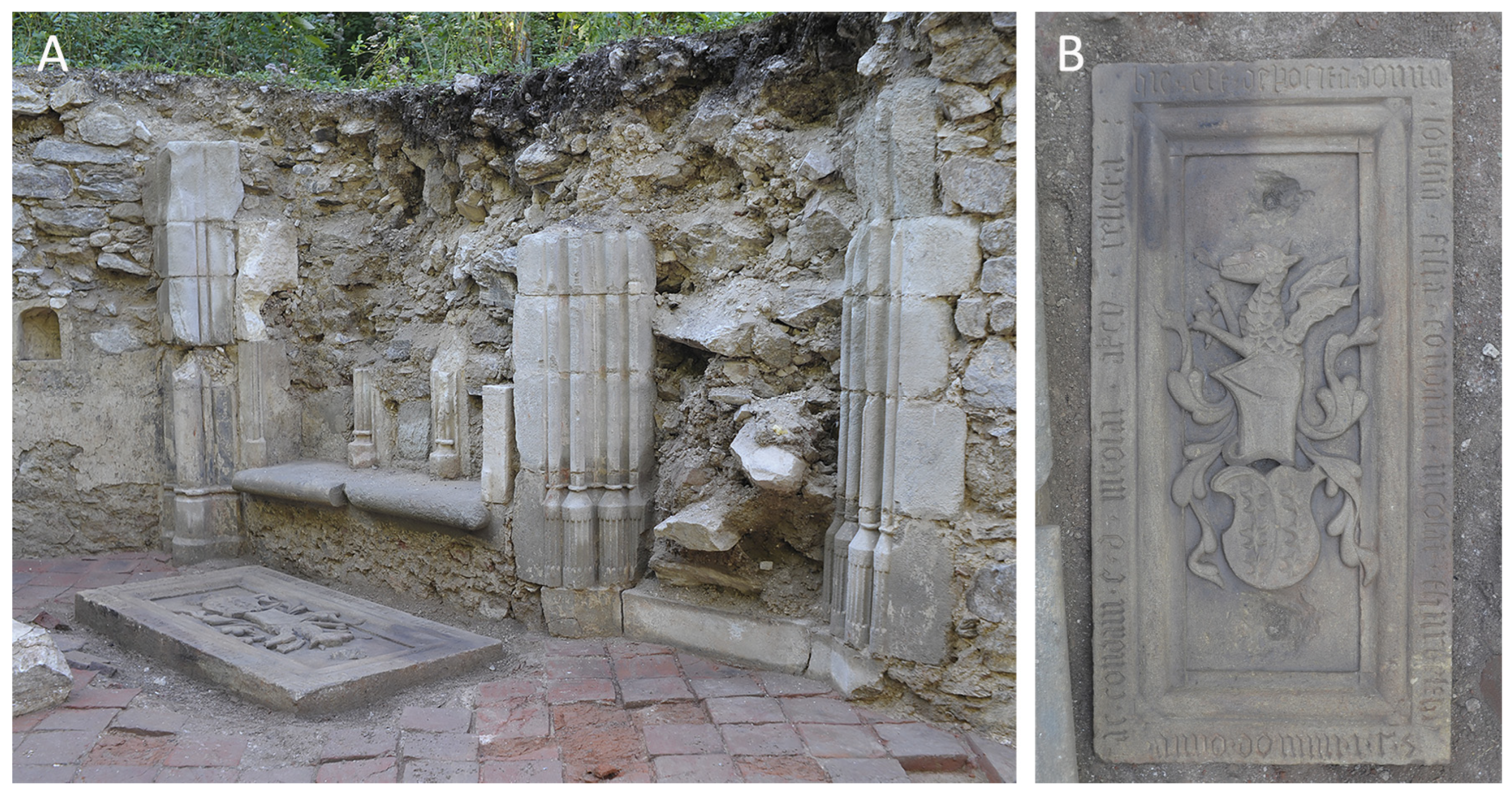

2.1. Archaeological Context

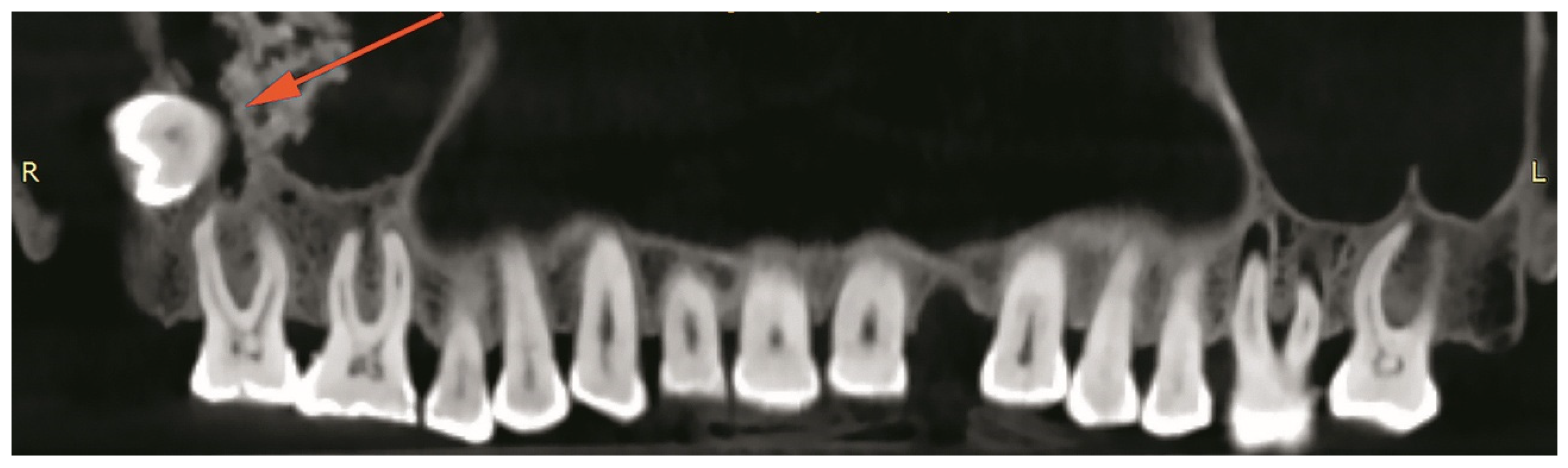

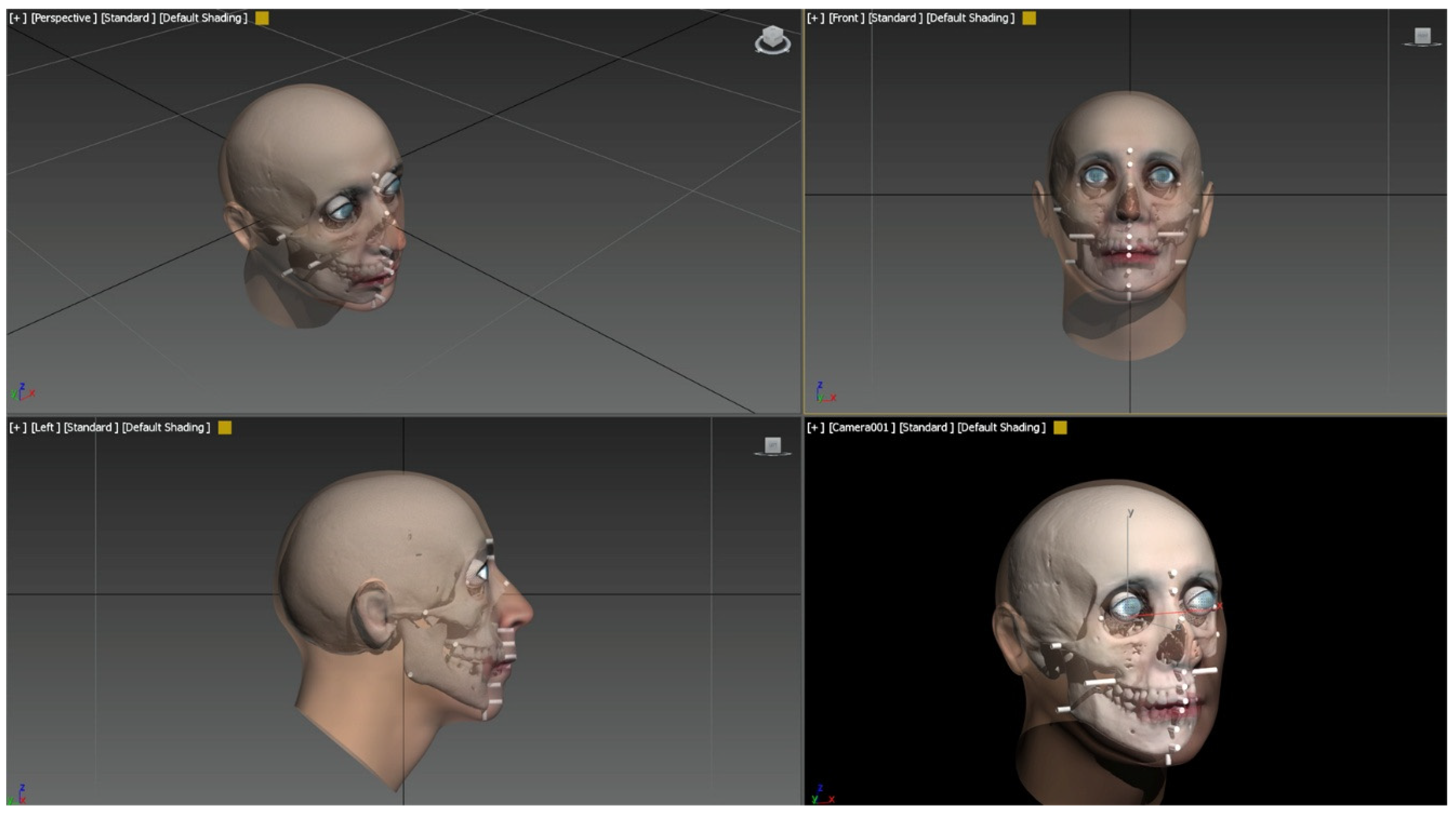

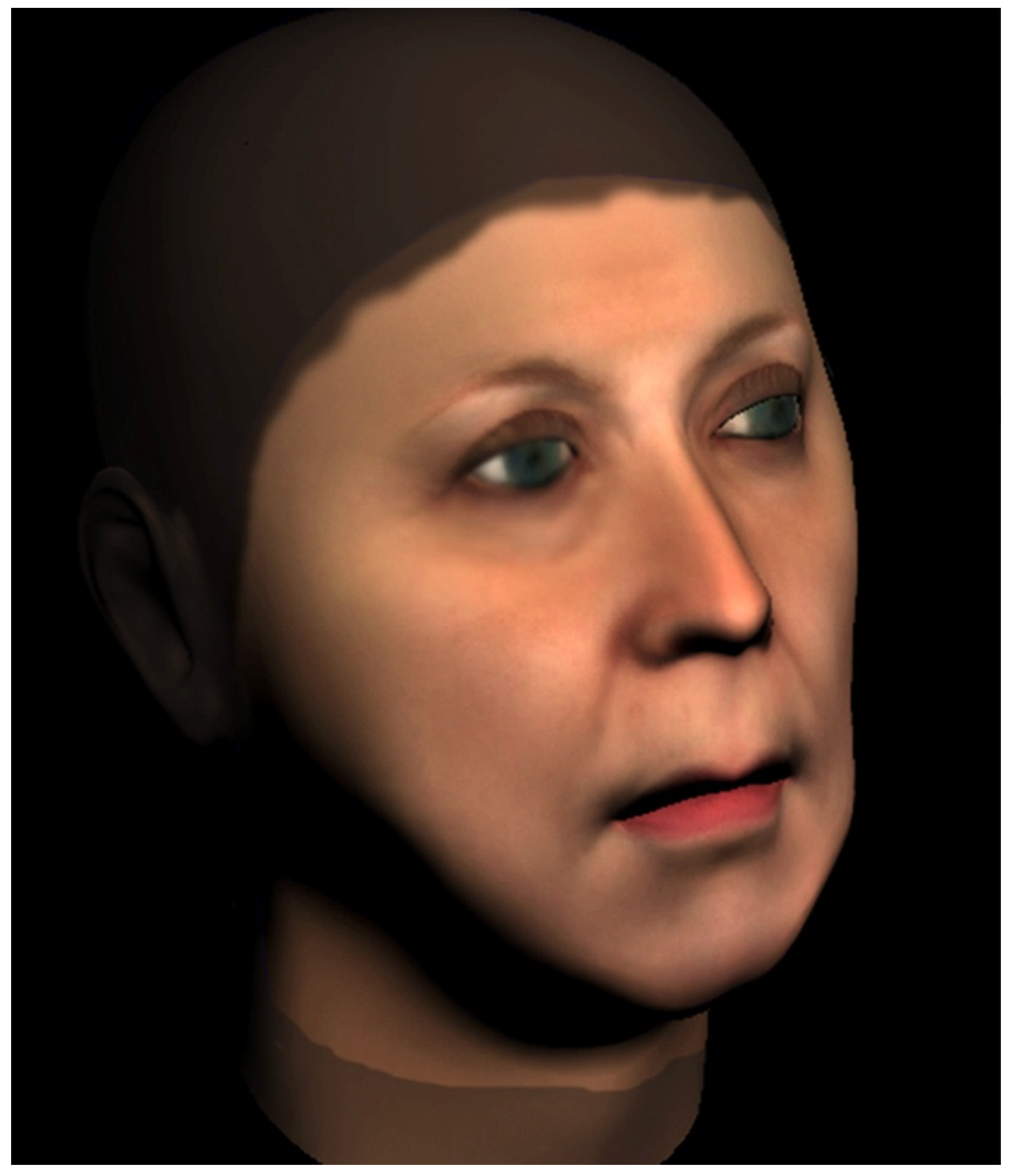

2.2. Analytical Methods

3. Results

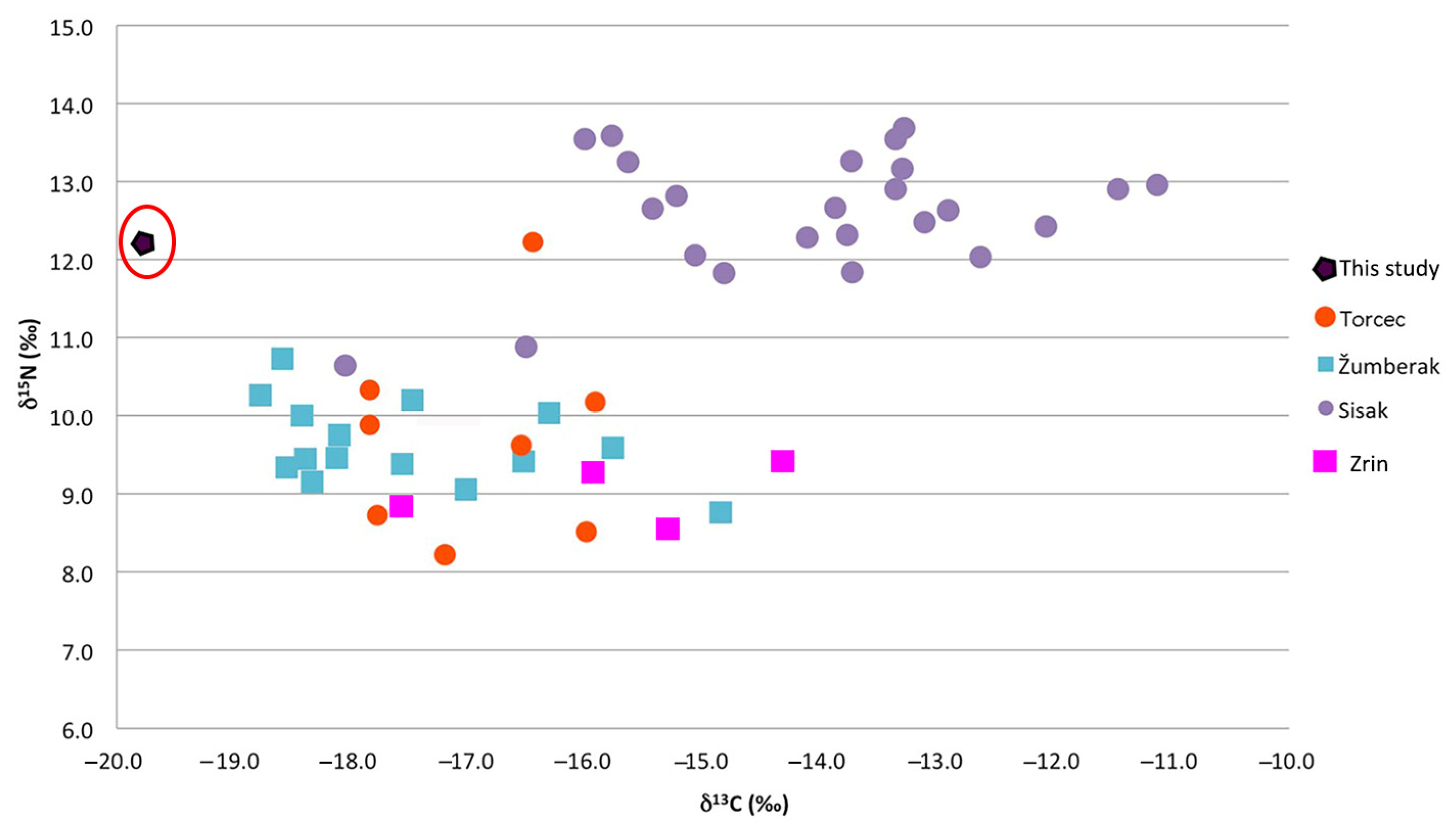

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saul, F.P. The Human Skeletal Remains of Altar de Sacrificios: An Osteobiographic Analysis; Peabody Museum Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Saul, F.P. Osteobiography: Life history recorded in bone. In The Measures of Man: Methodologies in Biological Anthropology; Giles, E.F., Scott, J., Eds.; Peabody Museum Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976; pp. 372–382. [Google Scholar]

- Saul, F.P.; Saul, J.M. Osteobiography: A Maya example. In Reconstruction of Life from the Skeleton; İşcan, Y.K., Kenneth, A.R., Alan, R., Eds.; Liss: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hosek, L.; Robb, J. Osteobiography: A platform for bioarchaeological research. Bioarch. Int. 2019, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterholtz, A.; Novak, M.; Carić, M.; Paraman, L. Death and burial of a set of fraternal twins from Tragurium: An osteobiographical approach. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2025, 62, 105071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.C.; Wesp, J.K. Exploring Sex and Gender in Bioarchaeology; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitte, S.N. Stress, sex, and plague: Patterns of developmental stress and survival in pre- and post-Black Death London. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2018, 30, e23073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, P.L. Identity and difference: Complicating gender in archaeology. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 2009, 38, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, P.L. The bioethos of osteobiography. Bioarchaeol. Int. 2019, 3, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihanović, F.; Jerković, I.; Kružić, I.; Anđelinović, Š.; Janković, S.; Bašić, Ž. From biography to osteobiography: An example of anthropological historical identification of the remains of St. Paul. Anat. Rec. 2017, 300, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šlaus, M.; Domić Kunić, A.; Pivac, T. Reconstructing the life of a Roman soldier buried in Resnik near Split, based on the anthropological analysis of his skeleton. Coll. Antropol. 2018, 42, 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Pleše, T. Ordo Sancti Pauli Primi Eremitae: Monasteries and the shaping of the late medieval Slavonian landscape prior to the Battle of Mohács (1526). In Monastic Europe: Medieval Communities, Landscapes, and Settlements; Krasnodebska-D’Aughton, M., Bhreathnach, E., Smith, K., Eds.; Brepols: Turnhout, Belgium, 2019; pp. 383–406. [Google Scholar]

- Klales, A.R. Sex Estimation of the Human Skeleton: History, Methods, and Emerging Techniques; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Buikstra, J.E.; Ubelaker, D.H. Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains; Arkansas Archaeological Survey: Fayetteville, NC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter, M.L. Estimation of stature from intact limb bones. In Personal Identification in Mass Disasters; Stewart, T.D., Ed.; Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History: Washington, DC, USA, 1970; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Aufderheide, A.C.; Rodríguez-Martín, C. The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Human Paleopathology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ortner, D.J. Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains; Academic Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, D.J.; Dean, M.C. The timing of linear hypoplasias on human anterior teeth. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2000, 113, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longin, R. New method of collagen extraction for radiocarbon dating. Nature 1971, 230, 241–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, G.E.; Deter, C.; Pitfield, R.; Miszkiewicz, J.J.; Mahoney, P. Bone deep: Variation in stable isotope ratios and histomorphometric measurements of bone remodelling within adult humans. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017, 87, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.; Telyakova, V. An overview of cone-beam computed tomography and dental panoramic radiography in dentistry in the community. Tomography 2024, 10, 1222–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasalainen, T.; Ekholm, M.; Siiskonen, T.; Kortesniemi, M. Dental cone beam CT: An updated review. Phys. Med. 2021, 88, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, C. Forensic Facial Reconstruction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, C. Facial reconstruction—Anatomical art or artistic anatomy? J. Anat. 2010, 216, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli, F. Postmortem CT and forensic identification: The role of facial approximation and craniofacial superimposition techniques. In Proceedings of the Abstracts Book of the 12th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Forensic Radiology and Imaging, Toulouse, France, 25–27 May 2023; International Society for Forensic Radiology and Imaging: Toulouse, France, 2023; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, C.N. Accuracies of facial soft tissue depth means for estimating ground truth skin surfaces in forensic craniofacial identification. Int. J. Legal Med. 2016, 129, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, C.N. The application of the central limit theorem and the law of large numbers to facial soft tissue depths: T-table robustness and trends since 2008. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, C.N. Facial approximation: Globe projection guideline falsified by exophthalmometry literature. J. Forensic Sci. 2002, 47, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, C.N. Facial approximation: An evaluation of mouth-width determination. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2003, 121, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rynn, C.; Wilkinson, C.; Peters, H.L. Prediction of nasal morphology from the skull. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2010, 6, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanz, V.; Vetter, T. A morphable model for the synthesis of 3D faces. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 8–13 August 1999; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1999; p. 187. [Google Scholar]

- Pálosfalvi, T. The Noble Elite in the County of Körös (Križevci) 1400–1526; Institute of History, Hungarian Academy of Sciences: Budapest, Hungary, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maček, P.; Jurković, I. Rodoslov Plemića i Baruna Kaštelanovića od Svetog Huha (od 14. do 17. Stoljeća); Hrvatski Institut za Povijest, Podružnica za Povijest Slavonije, Srijema i Baranje: Slavonski Brod, Croatia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Heka, L. Hrvatski ban: Prava i ovlasti tijekom tisućgodišnje opstojnosti, mađarska ustavno-povijesna perspektiva. Zb. Pravnog fak. Sveučilišta Rijeci 2023, 44, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbić, M. Položaj plemkinja u Slavoniji tijekom srednjeg vijeka. Hist. Zb. 2006, 59, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Krznar, S.; Hajdu, T. Late medieval/early modern population from Ivankovo, eastern Croatia: The results of the (bio)archaeological analysis. Pril. Instituta Arheol. Zagreb. 2020, 37, 165–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Bedić, Ž.; Los, D.ž.; Premužić, Z. Bioarchaeological analysis of the 15th–17th century population from Zrin, continental Croatia. Arheol. Rad. Raspr. 2021, 20, 317–326. [Google Scholar]

- Kriletić, B.; Ivanušec, D.; Carić, M.; Novak, M. The usual suspects: Deciphering the epidemiology, variation of injuries and lifestyle in Late Medieval / Early Modern population from Đakovo. Arheol. Rad. Raspr. 2024, 22, 211–234. [Google Scholar]

- Šlaus, M.; Pećina-Hrnčević, A.; Jakovljević, G. Dental disease in the late Medieval population from Nova Rača, Croatia. Coll. Antropol. 1997, 21, 561–572. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, M.; Šlaus, M.; Vyroubal, V.; Bedić, Ž. Dental pathologies in rural medieaval populations from continental Croatia. Anthropol. Közlemények 2010, 51, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, M.; Rimpf, A.; Bedić, Ž.; Krznar, S.; Janković, I. Reconstructing medieval lifestyles: An example from Ilok, eastern Croatia. Acta Musei Tiberiopolitani 2017, 2, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, M.; Bedić, Ž.; Vyroubal, V.; Krznar, S.; Rimpf, A.; Janković, I.; Lightfoot, E.; Šlaus, M. The effects of the Little Ice Age on oral health and diet in populations from continental Croatia. In Proceedings of the Scientific Program (With Abstracts) of the 44th Annual North American Paleopathology Association Meet-ing; New Orleans, LA, USA: 17–20 April 2017; Paleopathology Association: New Orleans, LA, USA, 2017; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Cronkhite, C.; Temple, D.H.; Osterholtz, A.; Valent, I.; France, C.A.M. Interindividual variation in infant child feeding behavior at Đurđevac-Sošice medieval Croatia: Exploring life course through incremental analysis of dentin. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2025, 182, 106357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillson, S. Dental pathology. In Biological Anthropology of the Human Skeleton; Katzenberg, A., Saunders, S.R., Eds.; Wiley-Liss: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 301–340. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, C.S. Bioarchaeology. Interpreting Behavior from the Human Skeleton; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, C.A.; Manchester, K. Archaeology of Disease; Sutton Publishing: Stroud, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Łukasik, S.; Krenz-Niedbala, M. Age of linear enamel hypoplasia formation based on Massler and colleagues’ and Reid and Dean’s standards in a Polish sample dated to 13th–18th century CE. HOMO 2014, 65, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakey, M.L.; Leslie, T.E.; Reidy, J.P. Frequency and chronological distribution of dental enamel hypoplasia in enslaved Americans: A test of the weaning hypothesis. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1994, 95, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, C.; Biehler-Gomez, L.; Lanza Attisano, G.; Gibelli, D.M.; Boschi, F.; De Angelis, D.; Cattaneo, C. Investigating the etiology and demographic distribution of enamel hypoplasia. Heritage 2025, 8, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinarić, D.; Lazanin, S. Zarazne bolesti, prostorna mobilnost i prevencija u ranome novom vijeku: Povijesna iskustva Dalmacije i Slavonije. Povij. Pril. 2021, 40, 9–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krznar, S.; Novak, M. A case of skeletal tuberculosis from St. John the Baptist site in Ivankovo near Vinkovci. Pril. Instituta arheol. Zagreb. 2013, 30, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lauc, T.; Fornai, C.; Premužić, Z.; Vodanović, M.; Weber, G.W.; Mašić, B.; Rajić Šikanjić, P. Dental stigmata and enamel thickness in a probable case of congenital syphilis from XVI century Croatia. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2015, 60, 1554–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šlaus, M.; Novak, M. A case of venereal syphilis in the Modern Age horizon of graves near the church of St. Lawrence in Crkvari. Pril. Instituta Arheol. Zagreb. 2007, 24, 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtović, E. Najmljeno dojenje i odgoj malodobne djece u Dubrovniku i dubrovačkom zaleđu u razvijenom srednjem vijeku. In Žene u Srednjevjekovnoj Bosni—Zbornik Radova; Filipović, O.E., Ed.; Društvo za Proučavanje Srednjevjekovne Bosanske Istorije: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2015; pp. 225–242. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić Jakus, Z. Profesija—Hraniteljica: Dojilje u dalmatinskim gradovima u srednjem vijeku. In IV Istarski povijesni biennale. Filii, Filiae ...: Položaj i Uloga Djece na Jadranskom Prostoru—Knjiga Sažetaka; Mogorović Crljenko, M., Ed.; Zavičajni Muzej Poreštine: Poreč, Croatia; Državni Arhiv u Pazinu: Pazin, Croatia; Sveučilište Jurja Dobrile u Puli: Poreč, Croatia, 2011; pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Čapo-Žmegač, J. Seoska društvenost. In Etnografija: Svagdan i Blagdan Hrvatskoga Puka; Čapo Žmegač, J., Muraj, A., Vitez, Z., Grbić, J., Belaj, V., Eds.; Matica Hrvatska: Zagreb, Croatia, 1998; pp. 251–295. [Google Scholar]

- Kokotović, T.; Carić, M.; Stingl, S.; Novak, M.; Belaj, J. Reconstructing life history of the 18th century priest from Prozorje, Croatia: Bioarchaeological and biochemical approaches. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2025, 66, 105294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Vyroubal, V.; Krnčević, Ž.; Petrinec, M.; Howcroft, R.; Pinhasi, R.; Šlaus, M. Assessing childhood stress in early mediaeval Croatia by using multiple lines of inquiry. Anthropol. Anz. 2018, 75, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, L.; di Tota, G. Etruscan teeth and odontology. Dent. Anthropol. 1993, 8, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotto, E.; Kurek, M.; Militello, P.M.; Platania, E.; Galassi, F.M. A case of impacted third molar from the prehistoric Hypogeum of Calaforno (Giarratana, Ragusa, Sicily): Reflections on the antiquity and evolutionary implications of this trait. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2025, 179, 106371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajić Šikanjić, P.; Premužić, Z.; Meštrović, S. Hide and seek: Impacted maxillary and mandibular canines from the Roman period Croatia. Int. J. Paleopathol. 2019, 24, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.J. Principles of management of impacted teeth. In Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; Peterson, L.J., Ellis, E., III, Hupp, J.R., Tuker, M.R., Eds.; Mosby: St. Louis, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 215–248. [Google Scholar]

- Juodzbalys, G.; Daugela, P. Mandibular third molar impaction: Review of literature and a proposal of a classification. J. Oral Maxillofac. Res. 2013, 4, e1. [Google Scholar]

- Šlaus, M.; Novak, M.; Bedić, Ž.; Vyroubal, V. Antropološka analiza kasnosrednjovjekovnog groblja kraj crkve Sv. Franje na Opatovini u Zagrebu. Arheol. Rad. Raspr. 2007, 15, 211–247. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, M.; Šlaus, M. Vertebral pathologies in two early Modern period (16th–19th century) populations from Croatia. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2011, 145, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, N.J. The timing of injuries and manner of death: Distinguishing among antemortem, perimortem and postmortem trauma. In Forensic Osteology: Advances in the Identification of Human Remains; Reichs, K.J., Ed.; C.C. Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 1998; pp. 321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Facchini, F.; Rastelli, E.; Belcastro, M.G. Peri mortem cranial injuries from a medieval grave in Saint Peter’s Cathedral, Bologna, Italy. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2007, 18, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J.P.; Williams, G.N.; Scoville, C.R.; Arciero, R.A.; Taylor, D.C. Persistent disability associated with ankle sprains: A prospective examination of an athletic population. Foot Ankle Int. 1998, 19, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnetzke, M.; Vetter, S.Y.; Beisemann, N.; Swartman, B.; Grützner, P.A.; Franke, J. Management of syndesmotic injuries: What is the evidence? World J. Orthop. 2016, 7, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermena, S.; Slane, V.H. Ankle Fracture; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, IL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa, D.R.C.; Duarte, F.A.; Saito, G.H.; Sorbini, E.S.; Sequim, V.; Pontin, P.A.; Fonseca, F.C.P.; Miranda, B.R.; Mendes, A.A.M.; Prado, M.P. Functional treatment of isolated stable Weber B fractures of the lateral malleolus with immediate weightbearing and joint mobilization. J. Foot Ankle. 2024, 18, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.P. Isotope analysis for diet studies. In Archaeological Science: An Introduction; Britton, K., Richards, M.P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Thorp, A. On isotopes and old bones. Archaeometry 2008, 50, 925–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stingl, S. Prehrana Kasnosrednjovjekovnih Elita na Primjeru na Primjeru Troškovnika Zagrebačkog Biskupa Osvalda Thuza iz 1481. i 1482. godine. PhD Thesis, Filozofski fakultet u Zagrebu, Zagreb, Croatia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tkalčec, T.; Trbojević Vukičević, T. Archaeozoological evidence of dietary habits of small castle inhabitants in the medieval Slavonia. In Castrum Bene 16. Castrum and Economy; Pisk, S., Ed.; Muzej Moslavine: Kutina, Croatia; Povijesna udruga: Popovača, Croatia, 2021; pp. 124–152. [Google Scholar]

- Korpes, K.; Piplica, A.; Đuras, M.; Trbojević Vukičević, T.; Kolenc, M. Exploitation of pigs during the Late Medieval and Early Modern Period in Croatia. Heritage 2024, 7, 1014–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpes, K.; Trbojević Vukičević, T.; Đuras, M.; Kolenc, M.; Piplica, A. Archaeozoological insights into the husbandry of domestic ruminants at monastic and noble sites in medieval Croatia. Quaternary 2025, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, K.; Smuk, A.; Tkalčec, T.; Balen, J.; Mihaljević, M. Food and agriculture in Slavonia, Croatia, during the Late Middle Ages: The archaeobotanical evidence. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 2022, 31, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.; Heinemeier, J.; Lübke, H.; Lüth, F.; Terberger, T. Dietary habits and freshwater reservoir effects in bones from a Neolithic NE German cemetery. Radiocarbon 2010, 52, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli, F. Ricostruire il volto. Approssimazione dei tratti facciali in archeologia. In AAVV Storie dal Confine Orientale. Storie e Volti Dalla Tarda Antichità al Medioevo nel Friuli Venezia Giulia Storico; Edizioni dell’Accademia Jaufré Rudel: Gradisca d’Isonzo, Italy, 2025; pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdu, T.; Borbély, B.; Bernert, Z.; Buzár, Á.; Szeniczey, T.; Major, I.; Cavazzuti, C.; Molnar, M.; Horvath, A.; Palcsu, L.; et al. Murder in cold blood? Forensic and bioarchaeological identification of the skeletal remains of Béla, Duke of Macsó (c. 1245–1272). Forens. Sci. Int. Genet. 2025, 81, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Novak, M.; Pleše, T.; Cavalli, F.; Janković, I. Reconstructing an Individual’s Life History by Using Multi-Analytical Approach: The Case of Sofia Kaštelančić née di Prata. Heritage 2025, 8, 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120540

Novak M, Pleše T, Cavalli F, Janković I. Reconstructing an Individual’s Life History by Using Multi-Analytical Approach: The Case of Sofia Kaštelančić née di Prata. Heritage. 2025; 8(12):540. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120540

Chicago/Turabian StyleNovak, Mario, Tajana Pleše, Fabio Cavalli, and Ivor Janković. 2025. "Reconstructing an Individual’s Life History by Using Multi-Analytical Approach: The Case of Sofia Kaštelančić née di Prata" Heritage 8, no. 12: 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120540

APA StyleNovak, M., Pleše, T., Cavalli, F., & Janković, I. (2025). Reconstructing an Individual’s Life History by Using Multi-Analytical Approach: The Case of Sofia Kaštelančić née di Prata. Heritage, 8(12), 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120540