3.1. Analysis and Results from Iconographic Research and Documentary Sources on the Domus

Building on prior studies of the House of Arianna, the research carried out within the CHANGES project approached the domus as a layered architectural palimpsest. To that end, historical and iconographic research were used as tools to decipher and interpret the processes of evolution, rediscovery, and restoration that have shaped the domus’ archaeological structures over time. The first explorations of Regio VII date to 1833, during the directorship of Francesco Maria Avellino, who initiated systematic excavation of this area, progressively uncovering Insulae 3 and 4. Between 1833 and 1837 the main houses of the block were brought to light, including the House of the Ancient Hunt (VII 4, 48), the House of the Black Wall (VII 4, 59), the House of the Figured Capitals (VII 4, 57), and the House of Arianna (VII 4, 31–51) [

12].

The principal sources documenting this intense activity are the excavation journals preserved in the State Archives and in the Archives of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. A key reference for understanding the house is Guglielmo Bechi’s

Report on the Excavations of Pompeii (1833–1834), accompanied by two plates that constitute one of the earliest graphic representations of the building and show the eastern walls still buried beneath the layer of lapilli [

13] (

Figure 7).

The excavation records attest to the extraordinary quality of the wall paintings, especially the famous fresco depicting Arianna abandoned by Theseus on Naxos—from which the domus takes its name—removed by the bourbon excavators and now displayed in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. Because of its architectural distinction and the quality of its decorations, the House of Arianna was among the most thoroughly documented buildings of the nineteenth century (

Figure 8). This was largely thanks to the architect Pietro Bianchi, then director of the Pompeii site, who intensified the practice of drawing and recording architectural remains during excavation. In accordance with the Bourbon regulations in force at the time [

14,

15], Bianchi coordinated a group of official draftsmen assigned to record mosaics, objects and paintings unearthed daily—among them Giuseppe Marsigli, Giuseppe Abbate, Nicola La Volpe, Michele and Serafino Mastracchio, and from 1842 Antonio Ala—whose works often provide the only surviving evidence of decorations later lost in the second half of the nineteenth century [

4].

In addition to the official draftsmen, the fame of the House of Arianna attracted numerous independent artists, including Giuseppe Mancinelli, Wilhelm Zahn, and Anton Theodor Eggers, whose works helped disseminate the image of Pompeii throughout European artistic and collecting circles.

The documentation of the House of Arianna coincided with the emergence of the

Scuola di Posillipo, a Neapolitan pictorial movement that, though rooted in naturalist and anti-academic impulses, found in the Vesuvian landscape and ruins a privileged ground for experimentation. Within this context belongs the works of Giacinto Gigante, who between 1835 and 1856 produced two watercolors dedicated to the House of Arianna: the first depicting the south-western corner of the northern peristyle, the second a complex view integrating the smoking Vesuvius in the background with the polychrome Ionic columns and the interior of the

oecus (

Figure 9a).

Alongside these artistic interpretations stand authors such as Nicola La Volpe and Antonio Ala (

Figure 9b), whose drawings exhibit greater formal and chromatic fidelity to the wall paintings. Of note is also the

Album of Pompeii by the Aragonese painter Bernardino Montañés, produced between 1849 and 1850 and consisting of about seventy watercolors, now preserved at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. His plates document with remarkable precision the decorative schemes of several Pompeian houses, including the House of Arianna, where he reproduced details from the

tablinum, the rooms opening onto the atrium and peristyle, as well as architectural elements such as the polychrome capitals and the puteal adorned with a leonine frieze [

6].

During the 1840s, the introduction of photography to Pompeii by Calvert Richard Jones and George Wilson Bridges radically transformed the modes of archaeological documentation. Yet, photographic images did not immediately replace drawing, which continued to serve as a medium of aesthetic interpretation and critical reconstruction of ruins. The nineteenth-century watercolors and copies dedicated to the House of Arianna therefore remain irreplaceable sources for understanding the site’s original decoration, now largely lost or altered (

Figure 10).

The study of documentary, iconographic, and archival sources has made it possible to reconstruct the articulation of the domus from the moment of its discovery, enabling a detailed description of its spaces and layout, as well as an in-depth examination of the restoration interventions carried out over time. These historical materials provided the interpretative framework through which the subsequent direct investigations—geometric survey, diagnostic analyses, and material assessments—could be contextualized and critically verified, ensuring that the case-study reconstruction is historically grounded and methodologically consistent.

At the time of the eruption of AD 79, the House of Arianna exhibited a configuration somewhat inconsistent with the canonical distribution of rooms in Roman houses, likely due to the earthquakes that struck Pompeii in the years preceding the eruption. In its current form, the house is distinguished by the amplitude and complexity of its layout, originally articulated on two levels and comprising about fifty rooms on the ground floor. Like the House of the Faun, the Domus was organized around two peristyles adorned with fountains and water basins, preceded by a large atrium tuscanicum. The tripartite arrangement—atrium, Ionic peristyle, Doric peristyle—is the result of a complex, stratified building process reflecting successive phases of expansion and functional reorganization of the residence. The house had three main entrances: the first, on the southern side along Via degli Augustali (VII 4, 31), led directly to the atrium; the second, to the north, opened onto the large peristyle near Via della Fortuna (VII 4, 51); the third, smaller entrance—no longer visible today—opened onto the Vicolo Storto and gave access to the service area.

The main entrance on Via

degli Augustali introduced, through the

fauces, a traditional

atrium tuscanicum flanked by two rooms probably converted into

tabernae. Around the

atrium unfolded a sequence of

cubicula and

alae with a regular plan on the western side—adjoining the House of the Figured Capitals—while the rooms bordering

Vicolo Storto show an irregular configuration, adapting to the street’s alignment. This part of the domus, largely devoid of decorated surfaces or prestigious elements, is distinguished by the presence of a

lararium with rich wall and floor decoration [

6]. This space was the object of a detailed diagnostic campaign conducted by colleagues from the Department of Earth, Environmental and Resource Sciences at the University of Naples Federico II, coordinated by Vincenzo Morra (

Figure 11). Analyses revealed the palette of pigments used in the frescoes, including the presence of prized Egyptian blue and cinnabar—rare and costly materials attesting to the ancient prestige of the house [

16]. The

tablinum, opening both to the atrium and to the central peristyle, served as a hinge between the southern residential and the more monumental sectors of the house. Two lateral corridors led to a richly painted

oecus with a window, slightly recessed with respect to the main axis of the building.

With its sixteen free-standing Ionic columns in grey tuff covered with stucco, the central peristyle ranks among the most iconic and representative spaces of the House of Arianna. Unearthed almost intact except for its entablatures, the colonnade is distinguished by Ionic capitals coated with a thick layer of stucco, decorated at the base with a broad band painted in wine-red, while the corners of the volutes are highlighted in a vivid blue—still partially visible today. The presence of color traces on the capitals made the domus a favored subject for draughtsmen, travelers and scholars, who sought to depict this emblematic space and investigate lesser-known aspects of Pompeian architecture. The traces of color extend beyond the capitals to the moldings and lower portions of the column shafts, which underwent an early ancient restoration aimed at concealing the original fluting through the application of a thick stucco layer.

As Guglielmo Bechi observed, “at the base of these columns, one can still see the iron hooks that held the cords of the

aulae or curtains that once enclosed this portico” [

13] (p. 4), evoking the monumental character of the space and its role in the domestic life of the house. The colonnade also encloses a large rectangular basin lined in

cocciopesto and painted blue, featuring a central fountain spout that must have animated the environment with water effects.

On the western side, the walls of the central peristyle contained two

cubicula, an exedra adorned with high-quality wall paintings, a staircase that probably led to the upper floor of the domus, an

apotheca, and a large

oecus-triclinium. The exedra, with its sky-blue walls, still preserves in situ fragments of its ancient fresco decorations “paintings of landscapes, trophies, and various ornaments, rendered with astonishing mastery, among which is the picture of an old man selling Cupids in a cage, like caged birds” [

13] (p. 4) (

Figure 12).

At the eastern end of the peristyle, another oecus provided access to a staircase leading to the upper floor of the house and to a subterranean lararium featuring the depiction of a serpent Agathodaimon, a benevolent, apotropaic figure recurring in Pompeian iconography as a symbol of prosperity, domestic protection, and fertility.

Crossing a

tablinum with a

tessellatum pavement of white tesserae bordered in black leads to the area of the northern peristyle, sometimes referred to as the Corinthian atrium. This area is slightly misaligned with respect to the general layout of the House of Arianna due to major transformations following the earthquake of AD 62, when five small rooms and a

lararium were built abutting the northern peristyle, resulting in the closure of the surrounding corridor. Although devoid of elaborate decorations, this area is characterized by twenty-four free-standing columns in tuff,

opus incertum, and brickwork, with Doric capitals and stucco coating. This finishing, dating to the post-earthquake rebuilding phase, was intended to homogenize the architectural surfaces of the columns, masking material discontinuities and enhancing their solidity, a practice widespread in Pompeian building sites and consistent with Vitruvian precepts [

17].

Nineteenth-century accounts—such as those by Bechi and by the Niccolini brothers—had already emphasised the monumental character of the complex, noting how the spatial sequence of atrium, tablinum, and peristyle was conceived along a carefully orchestrated axial perspective that linked the public sphere of representation to the more private dimension of the inner garden. The meticulous masonry, opus tessellatum pavements, and Fourth-Style wall decorations make this domus a privileged testimony to the evolution of Pompeian domestic architecture between the late Samnite period and the Augustan age.

The study of indirect sources also included an examination of the archival records held in the Scientific Archive of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, relating to the restoration interventions carried out on the domus over the course of the twentieth century.

This documentation, although partially incomplete, sheds light on the works undertaken to restore the continuity of the vaults in the underground spaces, achieved through the integration of missing portions with lightweight conglomerate and the filling of haunches with soil and pottery fragments recovered on site. Structural consolidation also involved the insertion of polypropylene fibres, as well as injections of mortar and binding mixtures.

The records examined—dating to the 1980s and 1990s—further reference additional restoration activities, including the revision and reconstruction of existing roof structures, the consolidation of masonry, the repair and waterproofing of wall crests, the replacement of decayed architraves, the consolidation and cleaning of detached plasters and stuccoes, and the anchoring of several columns in the northern peristyle.

However, this documentation is not sufficiently comprehensive to determine the full extent of the interventions carried out on the structures, making it necessary to strengthen the phase of direct analysis of the built fabric.

3.2. Results from Architectural Survey of the Domus of Arianna in Pompeii

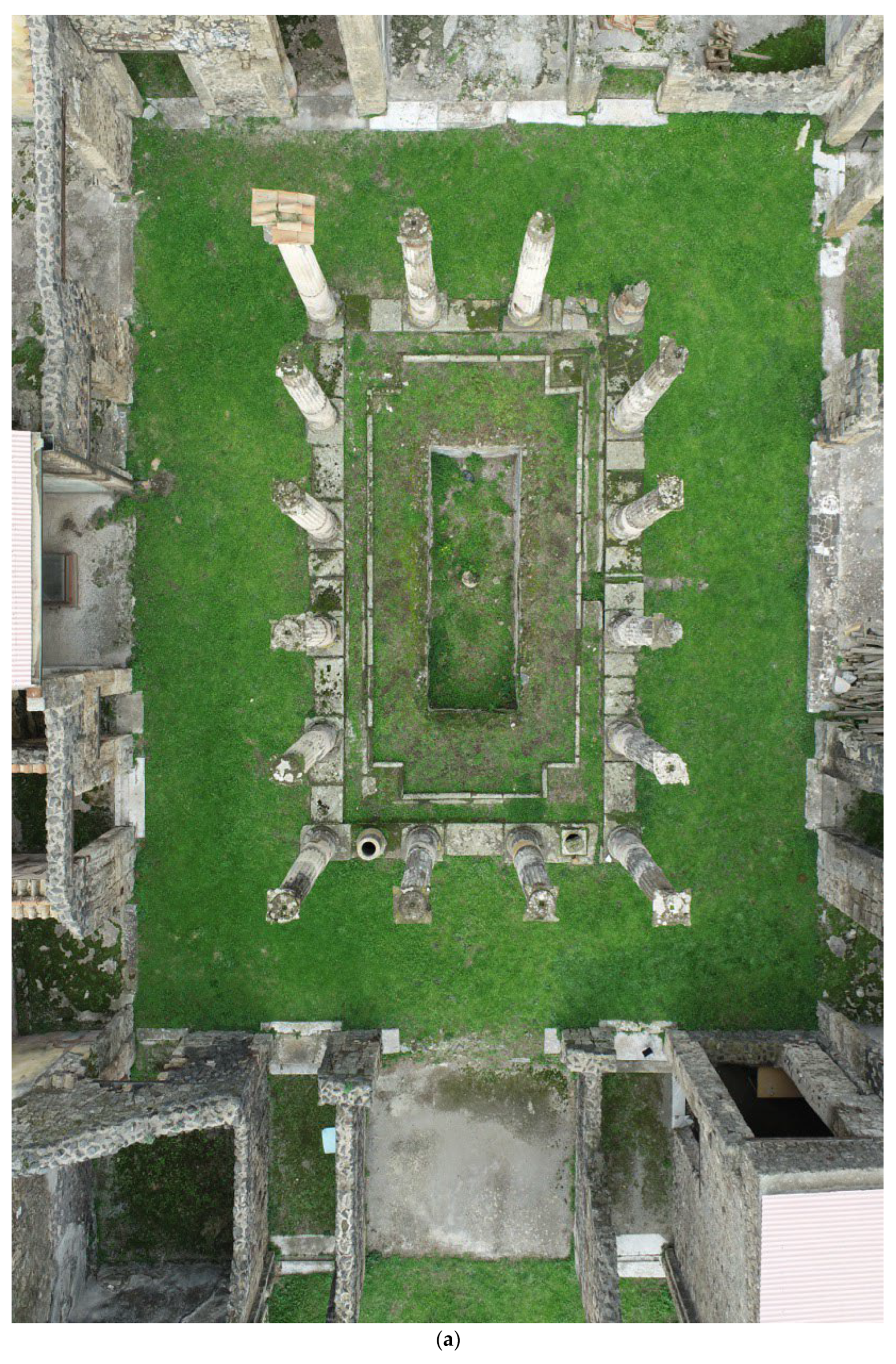

The study of indirect sources was consistently accompanied by an analysis of the material evidence through a detailed survey phase, conceived not merely as a recording exercise but as a critical tool for refining and verifying the data previously gathered during the documentary research stage (

Figure 13).

The considerable complexity of the architectural layout and the diversity of its decorative schemes required the adoption of technologies capable of capturing both morphological and material information, to be integrated directly within the digital modelling process. The architectural survey for conservation purposes must, in fact, contribute to achieving a comprehensive understanding of the monument, encompassing all aspects—from dimensional and constructional characteristics to chronological transformations, from its current state of preservation to static conditions and compositional principles.

The survey phase therefore operated as a non-invasive diagnostic examination of the monument, highlighting all the specific features that must be considered in the restoration design process.

Based on these premises, both range-based and image-based techniques were adopted. The acquisition of metric and material data was conducted using active optical-sensor technology, specifically the Laser Scanner FARO Focus3D X330 phase-shift laser scanner, which allowed the accurate and rapid definition of the topography of portions of the domus, at a level of precision difficult to achieve with conventional surveying instruments. Scans were carried out at a resolution of 6.136 mm, at a maximum range of 10 m in 3× quality mode, corresponding to a resolution of approximately 12.3 mm at that distance for the FARO Focus3D system.

The data obtained from the laser scanner survey, once processed, yielded a model perfectly consistent with the real structure, from which a significant quantity of information could be extracted: dimensional values, orthophotos, three-dimensional models, textures, and spherical images. The laser-scanning results were then integrated with photographic data captured via drone-mounted camera, which enabled improved visualization of the roof extradoses, wall crests, and pavements of the domus through orthogonal imagery. This comprehensive survey made it possible to carry out a detailed study of the construction techniques and the forms of structural damage and decay affecting the entire domus (

Figure 14).

Methodologically, each space within the house was assigned a progressive numerical code to ensure unambiguous identification. Within each room, surfaces were labelled using Arabic letters, in accordance with the cataloguing system of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii. This classification proved essential for identifying and mapping the construction techniques that characterize the domus within the digital model and for formulating preliminary hypotheses regarding the causes of the observed deformations and decay phenomena.

As part of the direct study of the House of Arianna, particular attention was devoted to identifying specific areas of investigation, defined according to the most pressing issues concerning the conservation of the archaeological fabric and the long-term preservation of the structures. Within this interpretative framework, two principal fields of study were selected: (a) the surfaces of the domus—both frescoed walls and pavement mosaic; (b) the free-standing columns in the two peristyles, a set rendered especially vulnerable by the absence of trabeation and by heterogeneous building techniques.

3.3. The Study to Preserve Architectural Surfaces: Mosaics and Frescoes in the House of Arianna

“The house featured a Tuscan porch overlooking the atrium, with walls adorned with splendid marbles and exquisite paintings. These decorations were lost when the impluvium was dismantled, and the embellishing ornaments were removed” [

18].

(p. 218)

The detailed description of House of Arianna provided by Giuseppe Fiorelli in 1875 in his work

Description of Pompeii attests to the symbiotic relationship between the house and the rich marble, mosaic, and pictorial decorations that once adorned its architectural surfaces, including both walls and floors. Indeed, House of Arianna, the central building of Insula 4 in Regio VII, has exemplified this relationship since its rediscovery in 1833 [

13], which revealed much of its polychrome decorative elements still preserved (

Figure 15).

Yet, Fiorelli’s description, which references a now-distant splendor, also testifies the nearly complete loss of the decorative furnishings of the recently excavated domus. Fragile testimonies to ancient taste and ways of life, the architectural and decorative surfaces of House of Arianna were already partially missing at the time of excavation—especially the marble decorations that must have enriched the walls of some rooms and the pool. Guglielmo Bechi, in his

Report on the Excavations of Pompeii, attributes these gaps to the actions of the ancient inhabitants themselves following the eruption: “All that remains of the base and the paintings is to convince us that the ancients themselves, who entered this house after the eruption, removed all the marble that adorned this atrium” [

13] (p. 2).

Despite the structural consolidation efforts undertaken immediately after the excavation, the gradual loss of the most precious and fragile materials within the domus remains evident today (

Figure 16). Currently excluded from the visitor routes of the Pompeii Archaeological Park, the ancient house faces significant conservation challenges affecting both its vertical and horizontal surfaces. The combined effects of atmospheric agents and aggressive weeds erode the frescoed walls and floors, leading to a slow but inexorable deterioration—partially mitigated by the essential safety and maintenance measures implemented by the Pompeii Archaeological Park.

Building on this foundation, special attention has been given to the interpretation and analysis of conservation issues affecting the site’s architectural surfaces. As part of a broader restoration and enhancement project encompassing Regio VII, a comprehensive plan for restoring and upgrading the artistic components of the domus will be essential, with particular focus on ensuring their safe in situ preservation. As we will observe, the in situ conservation of these artifacts—such as mosaics, frescoes, ceramics, and stucco decorations—is closely linked to considerations regarding accessibility and the broader use of the domus (

Figure 17).

For instance, the presence of floor mosaics in the spaces connecting the first and second peristyles presents a key design challenge from both a conservation perspective and in terms of the site’s functional reuse. The decision to preserve these mosaics in their original location influences the overall conservation strategy and inevitably complicates the development of accessibility plans for the ancient Roman residential complex.

A detailed survey was carried out to assess the condition of the structure. This process involved photogrammetric and geometric restitution of each room, followed by identification of degradation and alteration phenomena affecting the architectural surfaces, in accordance with the guidelines of

Lessico NorMal 11182/2006 [

19].

In evaluating the conservation status of House of Arianna, particular attention was given to issues currently impacting the floors—especially those decorated with mosaics—and the wall frescoes. Mapping and identifying the main conservation concerns represented a crucial initial step in understanding the property, essential for informing conservation strategies within the broader context of plans for reopening, enhancing, and restoring the entire insula.

3.3.1. Pavements with Mosaics

“Its entrance or hall n. 1 no longer shows any traces of its original decorations, except for a floor composed of a mixed brick and cement material, delicately adorned with white mosaics featuring lynxes elegantly intertwined” [

13].

(p. 1)

The evocative description of the entrance to House of Arianna, proposed by Bechi and later revisited by the brothers Fausto and Felice Niccolini in 1854 [

20], introduces us to a recurring compositional theme in the ancient domus: the presence of precious floor inlays between its main rooms [

13].

There are ten rooms in which traces of the ancient mosaic floor systems are still visible today, identified and described during the research (

Figure 17). The entrance room described by Bechi (room 1) had a

cocciopesto floor interspersed with a network of double meanders and rhombuses, geometrically inscribed in rhombuses or circles. The original compositional scheme was graphically represented by Niccolini in 1843, accompanied by a detailed descriptive note: “NB the lines that are red in this plan are nothing other than rows of white mosaic stones placed at an angle each measuring 10 millimeters square, on a pavement of lime and crushed brick” [

21] (p. 1). Few traces of this floor remain today: a condition confirmed during the restoration work carried out between 1979 and 1989. Larger portions of

opus signinum can be found in room 7 (

Figure 18); two-tone mosaics made up of black and white tiles are instead placed in the exedra room (room 24), in the passage between the two peristyles (room 28) and in the small room 52; floors in white tiles with a black perimeter band are located in rooms 21 and 26; and the richest and most complex floor mosaics, with central figurative decoration, are placed in the

lararium (room 13), room 20, the room containing the fresco of Theseus and Ariadne, and room 25, the rectangular exedra. The latter recalls a recurring theme in Roman domus, that of water, through the depiction of fish on a dark background, surrounded by a marble frame and light-colored tesserae.

The state of conservation of the mosaics is unfortunately aggravated by environmental conditions and direct contact with the ground: rising damp from the subsoil increases the level of tesserae decohesion, as do freeze–thaw cycles. This condition is further exacerbated by the emergence of spontaneous vegetation in all the environments described above. Due to the development of root systems of varying depth, this increases the disintegration of the bedding layer of the floor layers, leading to fractures in the subgrade and detachment of tesserae, which today lie erratically in almost every room of the domus (

Figure 19).

The Archaeological Park of Pompeii currently employs numerous measures to protect these floors, especially during the winter season: the installation of temporary protection systems to limit the action of rain and wind during the coldest months of the year limits the dispersion of erratic material and, at the same time, the increasingly significant process of grassing that plagues these areas.

However, a restoration intervention extended to the entire floor plan of the domus is an essential condition for their correct conservation Despite the serious state of conservation and the slow and gradual loss of the two-tone tessellation, these mosaics were in fact the subject of a systematic series of restoration interventions only in 1989: following the war damage of 1943, consolidation interventions carried out on the reinforcement of the walls and architraves and the installation of new roofing structures were considered priority, postponing the restoration interventions to be carried out on the decorative apparatus of the domus until a later date. The 1989 intervention carried out by the Archaeological Superintendency of Pompeii was grafted onto this ruinous state of conservation, a consequence of the war damage and the priority given to the consolidation of the wall components, as well as the more recent damage caused by the 1980 earthquake [

22]. Between 1987 and 1989, filling and restoration work was carried out on the floors, which at the time were largely lacking, sometimes even in the bedding layers: the mortar between the tiles was almost completely absent, increasing the level of detachment of entire fragments of the tessellated tiles, which were subject to complete loss of adhesion to the substrate. The gaps also affected the

cocciopesto and

opus signina floors, which were attacked by invasive vegetation. The state of conservation described above, and the related restoration work carried out are evidenced by the abundant photographic documentation—conducted both in the pre-restoration phase and during the delicate operations of weeding, cleaning, consolidation and reintegration—kept in the digital photographic archive of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii [

23].

3.3.2. Wall Frescoes’ Surfaces

“A larger triclinium follows the one described […] It was nobly painted and contained a picture with Ariadne asleep on the knees of Sleep, discovered by a Cupid at the approach of Bacchus, who, followed by his thiasos, contemplates her” [

18].

(pp. 219–220)

As for the other houses in Insula 4, during the research particular attention was paid to the reconnaissance and mapping of the state of conservation of the wall frescoes of the domus of Arianna still preserved in situ.

The most significant remains are concentrated on the walls of the exedra, on the south and west walls of room 14. (west wing, with

lararium), in the

oecus (room 17), room 20, and room 26. During the research, specific drawings were prepared for each room, detailing the layout of the walls (

Figure 20).

These drawings also included metric and material data, as well as data relating to the identified forms of deterioration. This methodology allowed for the creation of a map of the most frequently encountered forms of deterioration [

19]—detachments, stains, cracks, and chromatic alterations—attesting to the frescoes’ current state of conservation. This, too, is primarily due to the restoration work conducted during the twentieth century, concurrent with post-war repairs, which culminated in the restoration of the frescoes’ adhesion to the support and are extensively documented. The photographic evidence highlights, in particular, the symbiotic relationship between the ‘skin’ and the ‘structure’ of the domus, whereby the most serious cracks, damaging both the masonry and the decorative components, made the consolidation of the walls a priority, before moving on to the consolidation of the frescoes and, therefore, the re-adhesion of the frescoes to the walls.

Today, more than the loss of contact between frescoes and masonry, the surface problems related to the frescoes’ exposure to the environmental context and humidity are of concern.

Despite the protection systems present in the House of Arianna—both roofs and tiles placed around the perimeter above the decorated plasterwork—the frescoes, especially those located in the uncovered rooms, are affected by alterations and stains due to rainwater and rising damp from the ground, which, in many cases, has led to the loss of the chromatic component. A different state of conservation, however, affects the frescoes located in the covered rooms of the lararium and of the oecus which, thanks to the more effective contribution of the twentieth-century protective coverings, reveal more vivid colors and preserve their figurative nature intact.

For the frescoes, too, the research envisioned pre-consolidation, cleaning, surface consolidation, and protection interventions, differentiated according to the state of conservation of each surface. Recognizing direct exposure to the elements as a major factor in deterioration, conservation efforts focused on protecting the architectural surfaces of the open spaces, only partially protected by the tile systems. These, now obsolete, require updating to consider the conservation approaches historically employed on Pompeii’s buildings, with the goal of restoring and transmitting the historical material to the future, ensuring its legibility.

The high level of mosaic floors and wall frescoes makes the restoration of the architectural and decorated surfaces of House of Arianna a priority, marked by considerable technical and managerial complexity. This complexity is inherent in the fragility of these decorative elements, whose figurative quality must be protected to convey the narrative and importance of the domus to visitors. At the same time, it is rooted in the complex relationship between surface and structure, whose mutual interference requires an interdisciplinary and technically savvy approach for their proper conservation.

The interference between decoration and substrate is particularly critical when analyzing mosaic floor surfaces, especially in terms of use and accessibility. The House of Arianna plays a central role in terms of the fruition of Insula 4; ensuring its full use along its longitudinal axis would constitute a virtuous opportunity to traverse the entire insula, significantly improving the enjoyment not only of the domus itself, but also of the ancient settlement.

In the complex development of visitor itineraries for the domus of Insula 4, it was essential to consider potential interference with the remaining decorated remains. In this sense, it’s necessary to design a visit route through the domus consistent with the valuable archaeological remains. The solution evaluated in the research involved the replacement of the beaten earth flooring where deficient and the insertion of contemporary junctions (ramps and removable walkways) to ensure safe use of the house while preventing direct trampling on the floor surfaces. The connection between the two peristyles (room 28) proved particularly complex: still rich in erratic two-tone tesserae, this passageway required immediate intervention to secure and consolidate the floor support, which was most exposed to the walking of the domus users as it was the only room connecting the two peristyles. One possibility of use that guarantees the in situ preservation of the mosaic and, at the same time, easy access to the second peristyle from the first could be the insertion of a double ramp with a flat walkway that makes the underlying mosaic visible, a solution hypothesized and explored in the research presented here.

Ensuring the conservation of the mosaics in situ would increase the level of cognitive enjoyment of the domus, thanks to the natural process of contextualizing the mosaic or fresco perceived within the very environment in which it was conceived in antiquity: a condition that, after all, has been desired since the rediscovery of the city of Pompeii in the nineteenth century, later reaffirmed by the Valletta principles for the protection and management of the archaeological heritage [

24]. The careful design of technical and technological elements such as coverings for the frescoed surfaces and, at the same time, the definition of visitor routes that limit direct walking on the ancient mosaics would thus allow Arianna’s domus to pass on its precious story and its most authentic colors to the visitors of tomorrow.

3.4. Structural Fragility and Diagnostic Investigation of the Free-Standing Columns in the House of Arianna

Building on the previously discussed conservation issues affecting open-air archaeological structures in Pompeii, this section focuses on the specific vulnerabilities of the Free-Standing Columns in the House of Arianna (VII 4, 31–51). The loss of trabeations and bonding elements, together with the long-term exposure of its colonnaded spaces to environmental stressors, has rendered the peristyles both architecturally emblematic and structurally fragile (

Figure 21).

The two peristyles of different chronology and function [

6,

7] now represent the most critical element for the overall stability of the domus, which remains subject to multiple risk factors limiting its accessibility; indeed, the house is currently closed to the public. The repairs undertaken after the AD 62/63 earthquake and the restorations carried out following the nineteenth-century rediscovery (1832–1835) heightened this constructional heterogeneity, emphasizing the fragility of the open spaces of peristyles and identifying the columns as the weak point of the entire complex, hence the ongoing restrictions on visitor access. Direct examination of the domus, combined with an analysis of its static history—including the identification of past restorations and ongoing decay phenomena—proved crucial for understanding the structural behavior of the free-standing columns.

This process clarified several aspects of the material composition and construction logic of the two peristyles which, since antiquity, have represented the most vulnerable elements of the building. Recent archaeoseismological studies have demonstrated that these areas were already severely damaged by the earthquake that struck Pompeii prior to the eruption of AD 79. The event caused the overturning and collapse of the structures in the northern peristyle—later subject to significant post-seismic reconstruction—and inflicted serious damage on the central peristyle [

25].

The latter, dating to the second half of the second century BCE, consists of sixteen fluted grey-tuff columns coated with polychrome stucco, each measuring approximately 4.44 m in height and 53 cm in diameter. Among the most iconic features of the domus, these columns were redecorated during the Julio-Claudian period with vividly colored stuccoes that altered their original moldings and palette [

13,

20].

The northern peristyle, by contrast, dates to the Augustan period and comprises twenty-four columns of varying height with an average diameter of 46 cm, constructed using mixed techniques and materials—grey tuff, brick, limestone and

cruma—unified by a robust stucco coating with Doric flutes. The Doric-Tuscan capitals and Attic bases reflect a simplified architectural language typical of post-seismic reconstructions, consistent with the taste of the late Republican era [

26] (

Figure 22 and

Figure 23).

A closer analysis of the central peristyle proved essential for evaluating the structural behavior of the free-standing columns and assessing risk associated with their current configuration, independent shafts without upper connections.

Within the CHANGES Spoke 6 project, the diagnostic campaign on the columns of both the northern and central peristyles included thermographic and pacometric investigations, with the goal of examining the connections between stone drums, detecting material discontinuities and identifying areas of detachment not directly accessible due to the preservation of original finishing layers.

Although these methods do not allow exploration of the inner core of the columns, the measurements made it possible to identify historical consolidation systems used to re-adhere and stabilize stuccoes and plasters, consisting of small metal brackets and clamps inserted into the stone to depths of up to 3 cm and set radially.

Thermographic analysis highlighted the constructional heterogeneity of the northern peristyle’s masonry columns and revealed ongoing cracking and detachment processes in both colonnades. This allowed the immediate identification of the most vulnerable areas, enabling targeted stabilization and preventive measures to reduce the risk of material loss (

Figure 24a,b).

The internal configuration of the columns in the central peristyle was further investigated by means of high-frequency geophysical prospecting, applied to both the peristyle pavements and the vertical structures, to detect discontinuities, voids and inclusions not visible at the surface. GPR scans, carried out with a 400 MHz antenna for the pavements and with a very-high-resolution stepped-frequency system for the columns, revealed hyperbolic reflections and variations in the dielectric constant (εr) along the shafts of the central peristyle columns, interpreted as indicators of internal discontinuities. Longitudinal sections displayed an axial anomaly at approximately 1.50 m above ground level, corresponding to a vertically oriented trace compatible with a non-metallic connecting element between drums. These data were complemented by circumferential profiles at various elevations, which confirmed the absence of significant internal anomalies and revealed only micro-irregularities attributable to porosity or micro-fractures in the stone, without affecting the overall integrity and stability of the House of Arianna’s free-standing columns.

Although they do not provide a direct measure of load-bearing capacity, these results nonetheless offer valuable insight into construction processes, internal configurations and joint interfaces, forming the basis for the definition of conservation and maintenance strategies. The integration of these findings with earlier research on Pompeian peristyles has led to two hypotheses regarding the construction of the central peristyle columns. The first, based on comparisons with the western area of the Forum, posits a tenon connection between drums; the discovery in the

Vicolo del Gallo area of a similar element set in mortar within a square recess supports this technique, which notably excluded the use of lead, consistent with GPR results [

27].

The second hypothesis, based on research by the École française de Rome and the Centre Jean Bérard, interprets the detected discontinuity as the trace of a void related to turning processes and to the setting system for grey-tuff columns [

28,

29]. Studies on Campanian ignimbrite and stone-working techniques have demonstrated that tuff columns and capitals were shaped using vertical or horizontal stone lathes, as attested by parallelepiped mortises and axial cavities identified on ancient blocks. At the height of the mortise openings, chisel marks can often be observed along one or two adjacent sides of the bearing planes; these indicate the process used to release the inserted piece once the turning was completed. Although such evidence cannot be directly observed in the House of Arianna due to the integrity of the central peristyle columns, it finds a plausible correspondence in the irregular extent of the anomaly recorded through ground-penetrating radar analysis. Experimental replications have confirmed the feasibility of manually rotating tuff blocks weighing 250–300 kg on horizontal stone lathes to produce perfectly cylindrical shafts [

29]. The turning traces observed on the stone blocks of the columns in the central peristyle of the House of Arianna coincide with those documented in other Pompeian contexts, attesting to specialized workshops and semi-standardized techniques in the production and installation of these architectural elements [

30,

31].

Recent structural analyses have confirmed the consistency of the in situ geometric and material data, highlighting the physic-mechanical properties of Neapolitan grey tuff, a lightweight, highly porous material with compressive strengths between 1.4 and 2.4 MPa and an elastic modulus ranging from 900 to 1260 MPa. Numerical simulations conducted on representative models indicate that, under both static and seismic loads, the peristyle structures retain a generally stable elastic behavior, albeit with localized vulnerability to drum slippage at upper joints where adhesion is reduced [

32,

33].

These results confirm earlier diagnostic hypotheses regarding internal discontinuities and cavities, reinforcing the need for reversible, low-impact conservation measures aimed at mitigating risks of displacement and loss of cohesion without altering the original fabric.

Archival sources, particularly the

Libretto delle Misure dei Lavori di Pompei (1835–1839), further illuminate the history of the colonnades [

33]. The document records that, at the time of excavation, the ancient columns enclosing the central peristyle were found partly toppled and incomplete, with several drums missing. Twenty-five of these fragments were later recovered as excavations progressed and reassembled through experimental anastylosis: the drums were manually hoisted and repositioned using ropes and straps. The capital of the fourth column on the left side of the peristyle, discovered broken into two pieces, was initially secured with ropes to prevent collapse. It was later stabilized by inserting two iron clamps that rejoined the fragments into a single element. The capital thus consolidated was then placed in position on a bearing surface made of roof tiles [

34].

The

Misure dei Lavori also describes the placement of tiles as protective covers over the top of the last column on the left side of the central peristyle—“found intact upon discovery” [

34]—and the execution, on the capital, of a small built-up block in mortar and brick to ensure the necessary slope for rainwater runoff. (

Figure 25a,b).

At the base of the entrance side of the portico, another built-up block was constructed to fill and consolidate the ancient portion eroded by time, restoring its structural stability. These represent the most recent known consolidation interventions on the free-standing columns of the central peristyle; since then, the columns have not undergone further conservation work, except for occasional maintenance.

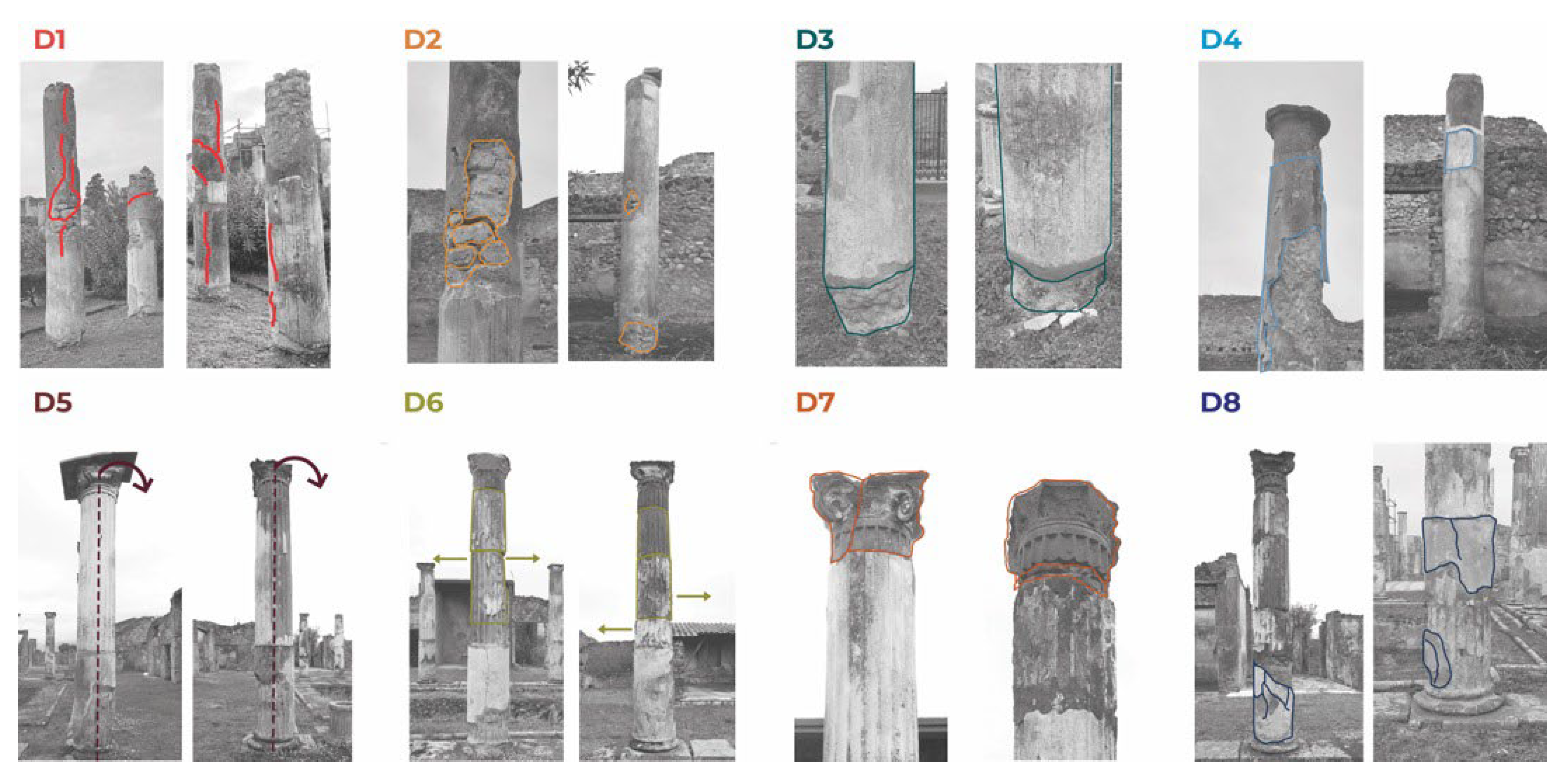

Although they appear broadly stable today, closer inspection reveals a gradual yet progressive material and structural decay. Exposed to the open air for nearly two centuries, the free-standing columns of the House of Arianna constitute a system vulnerable to multiple external agents: horizontal forces generated by wind and seismic activity, mechanical stresses linked to increasingly intense meteorological phenomena, and differential decay caused by ageing and alteration of constituent materials. The main pathologies observed include combined compression–bending deformation of the shafts, cracking and section loss at the base, detachment and disintegration of stucco layers, oxidation of metal cramps, out-of-plumb alignments, drum slippage, and localized fractures in the capitals.

Results from direct investigation confirmed the presence of discontinuities and internal anomalies within the columns of the central peristyle. These data support the hypothesis that internal connecting elements were originally employed, an interpretation currently under further study. Pacometric testing in the northern peristyle also revealed historical consolidation systems made of metal components inserted into the columns during interventions intended to preserve ancient plaster surfaces.

The diagnostic evidence obtained corresponds closely with archival documentation, which describes the use of metal clamps set radially to stabilize the structures. However, these historic inserts have since become a source of deterioration, particularly in areas where the original stucco coatings now exhibit fracturing, powdering, and detachment associated with the corroding metal elements (

Figure 26).

Collectively, these findings underline that the columns of the central peristyle suffer from a combination of structural and material vulnerabilities—including crushing of the free-standing shafts, voids and discontinuities, reduction in base sections, fracturing and detachment of plaster, overturning tendencies, drum slippage, and capital fractures. These conditions call for restoration strategies that respect the fragility of the archaeological fabric and are conceived as reversible, compatible, and adaptable to future reassessment through ongoing monitoring and maintenance.

The research undertaken at the House of Arianna underscores the pivotal role of interdisciplinary approaches in the conservation and restoration of archaeological heritage. Through the combined application of non-destructive diagnostics, structural analysis, and archival investigation, the project has not only contributed to the physical preservation of ancient architecture but also deepened our understanding of the materials, construction techniques, and historical interventions that have shaped the site over time. The knowledge gained from this integrated approach provides a robust foundation for sustainable, evidence-based restoration practices, ensuring the long-term preservation and cultural transmission of this exceptional example of Roman domestic architecture.