Chemical Investigation of Sicilian Red-Figure Pottery: Provenance Hypothesis on Vases from Gela (Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sicilian Red-Figures Vases from Gela

2.2. Analytical Methods

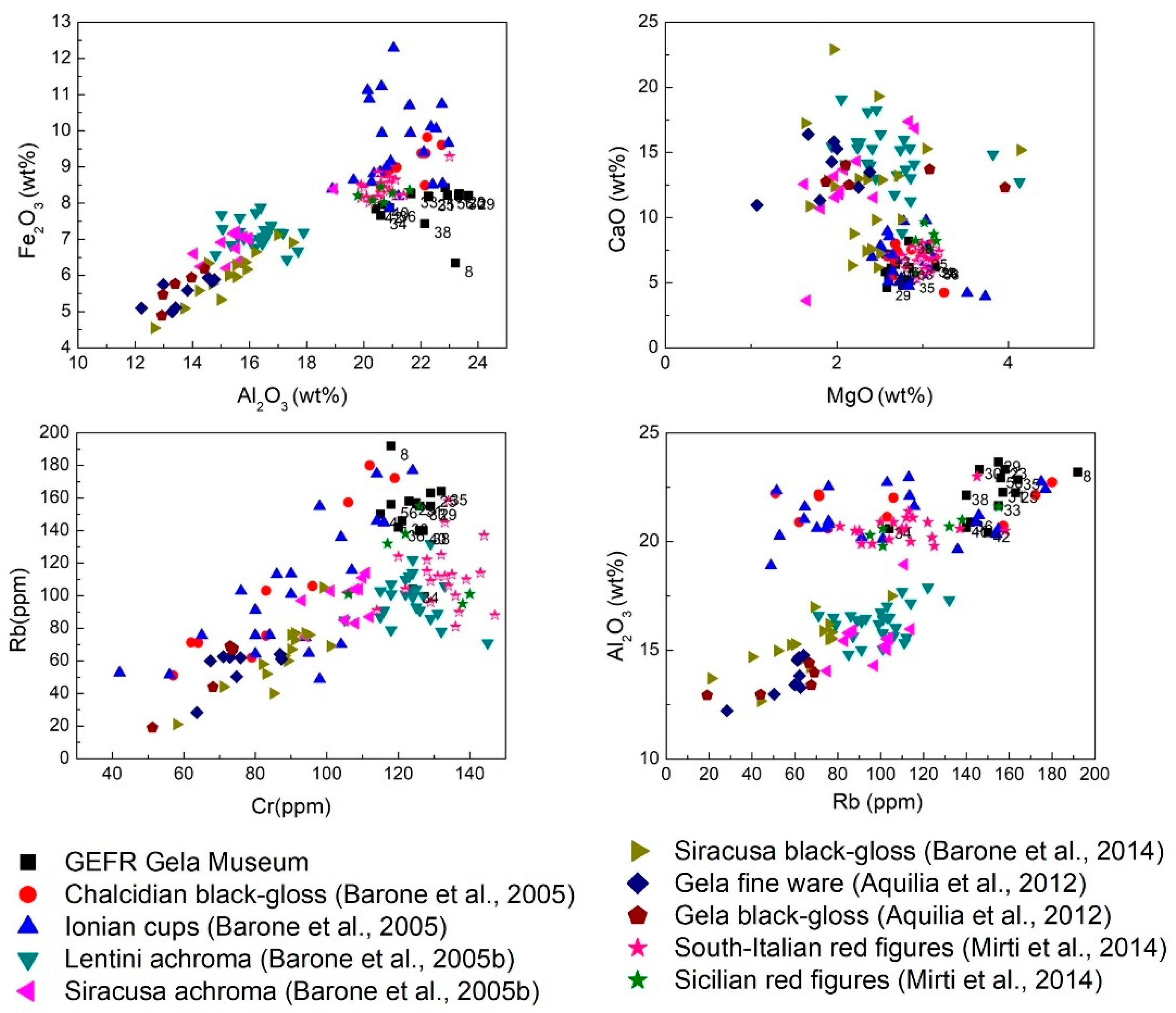

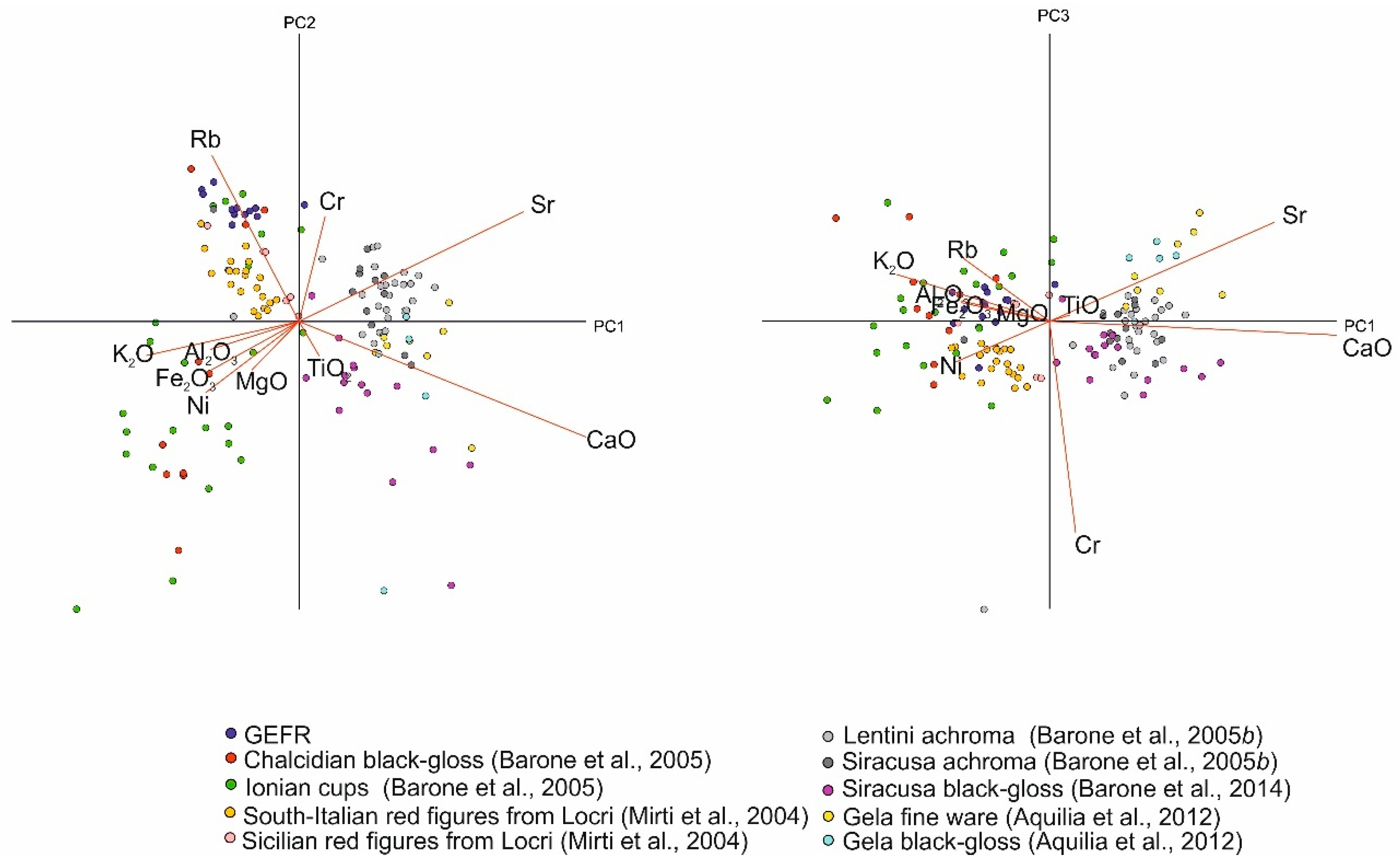

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trendall, A.D. The Red-Figured Vases of Lucania, Campania and Sicily; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1967; pp. 189–221, 575–664. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, A.D. The Red-Figured Vases of Lucania, Campania and Sicily, Third Supplement; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, A.D. The Red-Figured Vases of Paestum; The British School at Rome: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, A.D. Red Figure Vases of South Italy and Sicily. A Handbook; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Denoyelle, M.; Iozzo, M. La Céramique Grecque d’Italie Mériodionale et de Sicile. Productions Coloniales et Apparentées du VIIIe au IIIe Siècle av. J.-C.; Picard: Paris, France, 2009; ISBN 9782708408395. [Google Scholar]

- Todisco, L. (Ed.) La Ceramica a Figure Rosse della Magna Grecia e della Sicilia, I–III; L’Erma di Bretschneider: Roma, Italy, 2012; ISBN 9788882656201. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Aglio, A. La forma della città: Aree e strutture di produzione artigianale. In Taranto e il Mediterraneo, Atti del 41esimo Convegno di Studi sulla Magna Grecia; Istituto per la Storia e l’Archeologia della Magna Grecia (ISAMG): Taranto, Italy, 2002; pp. 171–193. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestrelli, F. Le fasi iniziali della ceramica a figure rosse nel kerameikos di Metaponto. In La Céramique Apulienne Bilan et Prospectives, Actes de la Table Ronde Organisée par l’École Française de Rome; Denoyelle, M., Lippolis, E., Mazzei, M., Pouzadoux, C., Eds.; Centre Jean Bérard: Naples, Italy, 2005; pp. 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, M.L. Aree e Quartieri Artigianali in Magna Grecia; Dipartimento di Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale dell’Università Degli Studi di Salerno: Capaccio, Italy, 2019; ISBN 9788887744842. [Google Scholar]

- Santostefano, A. Studio multidisciplinare sulla ceramica a figure rosse siceliota: Una produzione dall’area dello Stretto? Arch. Stor. Messin. 2025, 105, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Pappalardo, E.; Merendino, A.; Idà, L.; Vaccaro, M. Attività di ricerca archeologica in contrada Acquafredda/Imbischi (Castiglione di Sicilia) del DiSFor UNICT e della Soprintendenza di Catania (relazione preliminare). Cronache Archeol. 2023, 42, 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Barresi, S.; Merendino, A.; Pappalardo, E. L’officina del vasaio di Acquafredda/Imbischi (Castiglione di Sicilia). In Dialoghi sull’Archeologia della Magna Grecia e del Mediterraneo, Atti del IX Convegno Internazionale di Studi; Fondazione Paestum-Pandemos: Paestum, Italy, 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Spigo, U. La ceramica siceliota a figure rosse: Variazioni sul tema. Boll. Arte 1987, 44–45, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, D. La diffusione della ceramica figurata a Locri Epizefiri nella prima metà del IV secolo: Problemi di stile, produzione e cronologia. In La Céramique Apulienne. Bilan et Prospectives, Actes de la Table Ronde; Denoyelle, M., Lippolis, E., Mazzei, M., Pouzadoux, C., Eds.; Centre Jean Bérard: Naples, Italy, 2005; pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, D. Locri Epizefiri VI. Nelle Case di Ade. La Necropoli in Contrada Lucifero. Nuovi Documenti; Edizioni dell’Orso: Alessandria, Italy, 2010; ISBN 9878862742214. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, D. Birth and development of red-figured pottery between Sicily and South Calabria. In The Contexts of Painted Pottery in the Ancient Mediterranean World (Seventh-Fourth Centuries BCE); Paleothodoros, D., Ed.; BAR-IS 2364; BAR-IS: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, D. Il Gruppo di Locri in Calabria meridionale: Sviluppo di una tradizione siceliota. In Mobilità dei Pittori e Identità Delle Produzioni; Denoyelle, M., Pouzadoux, C., Silvestrelli, F., Eds.; Centre Jean Bérard: Naples, Italy, 2018; pp. 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Barresi, S. Sicilian Red-Figure Vase Painting. In Sicily. Art and Invention Between Greece and Rome; Lyons, C.L., Bennett, M., Marconi, C., Eds.; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 210–219. [Google Scholar]

- Barresi, S. Sicilian Red-figure Vase-painting: The Beginning, the End. In The Regional Production of Red-Figure Pottery: Greece, Magna Graecia and Etruria; Sabetai, V., Schierup, S., Eds.; Aarhus University Press: Aarhus, Denmark, 2014; pp. 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Barresi, S. Il Gruppo di Locri in Sicilia. In Mobilità dei Pittori e Identità Delle Produzioni; Denoyelle, M., Pouzadoux, C., Silvestrelli, F., Eds.; Centre Jean Bérard: Naples, Italy, 2018; pp. 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Spigo, U. Brevi considerazioni sui caratteri figurativi delle officine di ceramica siceliota della prima metà del IV secolo a. C. e alcuni nuovi dati. In La Sicilia dei due Dionisî, Atti della Settimana di Studio; Bonacasa, N., Braccesi, L., De Miro, E., Eds.; L’Erma di Bretschneider: Rome, Italy, 2002; pp. 265–293. [Google Scholar]

- Serino, M. La Bottega del Pittore di Himera e le Altre Officine Protosiceliote. Stile, Iconografia, Contesti, Cronologia; Scienze e Lettere: Rome, Italy, 2019; ISBN 9788866871521. [Google Scholar]

- Serino, M. Attic influences, Italiote experiences. The beginnings of red-figure pottery production in Sicily. In Μεγίστη καὶ Ἀρίστη Νῆσος, Symposium on Archaeology of Sicily; Fuduli, L., Lo Monaco, V., Eds.; Arbor Sapientiae: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Spigo, U. Rapporti fra Lipari e l’area dello Stretto di Messina nel IV sec. a.C. e nella prima età ellenistica. In Messina e Reggio Nell’antichità: Storia, Società, Cultura, Atti del Convegno della S.I.S.A.C.; Gentili, B., Pinzone, A., Eds.; Rubbettino: Soveria Mannelli, Italy, 2002; pp. 47–81. [Google Scholar]

- Spigo, U. Presenze di ceramica figurata siceliota di età dionigiana (e non solo…) a Messina. Sicil. Antiq. 2025, 22, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Santostefano, A. Riferimenti cronologici per la ceramica a figure rosse siceliota tra V e IV sec. a.C. Quad. Archeol. Univ. Messina 2020, 10, 75–108. [Google Scholar]

- Serino, M. Forma e immagine nelle officine protosiceliote. Una rilettura degli “inizi” delle prime produzioni a figure rosse attraverso possibili indizi di mobilità artigianale tra Campania e Sicilia. In Forma e Immagine, International Conference Proceedings; Salvadori, M., Baggio, M., Eds.; Poligrafo Casa Editrice: Padova, Italy, 2022; pp. 137–162. [Google Scholar]

- Serino, M. Some New Perspectives on the Study of Craftspeople’s Mobility in the Red-figure Pottery Production of Magna Graecia and Sicily. In People on the Move Across the Greek World; Mauro, C.M., Chapinal-Heras, D., Valdés Guía, M., Eds.; Editorial Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2022; pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Serino, M. From Micro to Macro, and Vice Versa. Technology Studies and Network Analysis on Red-figure Vase Production, between Sicily and Campania. In Technology, Crafting and Artisanal Network in the Greek and Roman World. Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Study of Ceramics; Elia, D., Hasaki, E., Serino, M., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 223–240. [Google Scholar]

- Denoyelle, M.; Pouzadoux, C.; Silvestrelli, F. (Eds.) Mobilità dei Pittori e Identità delle Produzioni; Cahiers du Centre Jean Bérard: Naples, Italy, 2018; ISBN 9782918887805. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, T. Potters and mobility in southern Italy (500–300 BCE). In Production, Trade, and Connectivity in Pre-Roman Italy; Armstrong, J., Cohen, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 82–98. [Google Scholar]

- Adamesteanu, D. Uno scarico di fornace ellenistica a Gela. Archeol. Class. 1954, 6, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Mangone, A.; Giannossa, L.C.; Ciancio, A.; Laviano, R.; Traini, A. Technological features of Apulian red figured pottery. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2008, 35, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangone, A.; Giannossa, L.C.; Colafemmina, G.; Laviano, R.; Traini, A. Use of various spectroscopy techniques to investigate raw materials and define processes in the overpainting of Apulian red figured pottery (4th century BC) from Southern Italy. Microchem. J. 2009, 92, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangone, A.; Caggiani, M.C.; Giannossa, L.C.; Eramo, G.; Redavid, V.; Laviano, R. Diversified production of red figured pottery in Apulia (Southern Italy) in the late period. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannossa, L.C.; Mininni, R.M.; Laviano, R.; Mastrorocco, F.; Caggiani, M.C.; Mangone, A. An archaeometric approach to gain knowledge on technology and provenance of Apulian red-figured pottery from Taranto. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2016, 9, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannossa, L.C.; Muntoni, I.M.; Forleo, T.; Patete, S.; Pouzadoux, C.; Laviano, R.; Mangone, A. Artisanal Experiences in Arpi: Colours and Raw Materials of Apulian Red Figure Production. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2022, 45, 103618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, G.; Di Bella, M.; Mastelloni, M.A.; Mazzoleni, P.; Quartieri, S.; Raneri, S.; Sabatino, G. Pigments characterization of polychrome vases production at Lipára: New insights by noninvasive spectroscopic methods. X-Ray Spectrom. 2018, 47, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, D.; Davit, P.; Re, A.; Gulmini, M. Magnific Magnification at Locri Epizephyrii: An Insight into the Surface of Western Red-figured Vases. In Technology, Crafting and Artisanal Network in the Greek and Roman World. Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Study of Ceramics; Elia, D., Hasaki, E., Serino, M., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Mirti, P.; Gulmini, M.; Pace, M.; Elia, D. The provenance of red figure vases from Locri Epizephiri (Southern Italy): New evidence by chemical analysis. Archaeometry 2004, 46, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannossa, L.C.; Muntoni, I.M.; Laviano, R.; Mangone, A. Building a step by step result in archaeometry. Raw materials, provenance and production technology of Apulian Red Figure pottery. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 43, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doménech-Carbó, A.; Giannuzzi, M.; Mangone, A.; Giannossa, L.C. Electrochemical methods to discriminate technology and provenance of Apulian red-figured pottery. II: EIS. Archaeometry 2022, 64, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conventi, A.; D’Ignoti, K.D.; Lazzarini, L.; Tesser, E. Archaeometric investigations of the materials and techniques of two red figured kraters by the Painter of Louvre K 240. Techné 2020, 49, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, A.; Kilikoglou, V. Ceramic raw materials: How to recognize them and locate the supply basins: Chemistry. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandini, P. Tipologia e cronologia del materiale archeologico di Gela dalla nuova fondazione di Timoleonte all’età di Ierone II. Archeol. Class. 1957, 9, 44–75. [Google Scholar]

- Adamesteanu, D.; Orlandini, P. Gela. L’acropoli di Gela. Not. Degli Scavi 1962, 16, 340–408. [Google Scholar]

- De Miro, E.; Fiorentini, G. Gela: Scavi dell’acropoli 1973–1975. Kokalos 1976–1977, 22–23, 430–447. [Google Scholar]

- Santostefano, A. Gela, Molino a Vento. Gli isolati I e II (scavi Orlandini 1955–1961); Dipartimento di Civiltà Antiche e Moderne dell’Università degli Studi di Messina: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 9788854915961. [Google Scholar]

- Santostefano, A. Un nuovo skyphos del Gruppo di Locri dall’acropoli di Gela. In Mobilità dei Pittori e Identità delle Produzioni; Denoyelle, M., Pouzadoux, C., Silvestrelli, F., Eds.; Cahiers du Centre Jean Bérard: Naples, Italy, 2018; pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Cufí, M.; Thió-Henestrosa, S. CoDaPack 2.0: A stand-alone, multi-platform compositional software. In Proceedings of the CoDaWork’11: 4th International Workshop on Compositional Data Analysis, Sant Feliu de Guíxols, Spain, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, G.; Mazzoleni, P.; Spagnolo, G.; Raneri, S. Artificial neural network for the provenance study of archaeological ceramics using clay sediment database. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 38, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, G.; Ioppolo, S.; Majolino, D.; Migliardo, P.; Sannino, L.; Spagnolo, G.; Tigano, G. Contributo delle analisi archeometriche allo studio delle ceramiche provenienti dagli scavi di Messina. Risultati preliminari. In Da Zancle a Messina. Un percorso Archeologico Attraverso gli Scavi; Bacci, M.G., Tigano, G., Eds.; Regione siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e Ambientali e della Pubblica Istruzione: Messina, Italy, 2002; Volume II, pp. 87–117. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, G.; Ioppolo, S.; Majolino, D.; Branca, C.; Sannino, L.; Spagnolo, G.; Tigano, G. Archaeometric analyses on pottery from archaeological excavation in Messina (Sicily, Italy) from the Greek archaic to the Medieval age. Period. Mineral. 2005, 74, 11–41. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, G.; Lo Giudice, A.; Mazzoleni, P.; Pezzino, A. Chemical characterization and statistical multivariate analysis of ancient pottery from Messina, Catania, Lentini and Siracusa (Sicily). Archaeometry 2005, 47, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, G.; Mazzoleni, P.; Aquilia, E.; Barbera, G. The Hellenistic and Roman Syracuse (Sicily) Fine Pottery Production Explored by Chemical and Petrographic Analysis. Archaeometry 2014, 56, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilia, E.; Barone, G.; Mazzoleni, P.; Ingoglia, C. Petrographic and chemical characterisation of fine ware from three Archaic and Hellinistic kilns in Gela (Sicily). J. Cult. Herit. 2012, 13, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, D. Nuovi dati sulla produzione e sulla circolazione della ceramica italiota a figure rosse nel IV secolo a.C. a Locri Epizefiri. In Archaeological Methods and Approaches: Industry and Commerce in Ancient Italy, Proceedings of the Conference, American Academy in Rome-École Française de Rome; De Sena, E.C., Dessales, H., Eds.; BAR-IS 1262; BAR-IS: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Spigo, U. Esemplari di ceramica siceliota ed italiota a figure rosse e sovradipinta al Museo Regionale di Messina. Quad. Mus. Reg. Messina 1992, 2, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Spigo, U. Nuovi rinvenimenti di ceramica siceliota da Lipari e dalla provincia di Messina. In The Archaeology of the Aeolian Islands, Proceedings of the Conferences Held at the Universities of Melbourne and Sydney; Descœudres, J.P., Ed.; Meditarch: Sydney, Australia, 1993; Volume 5/6, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Spigo, U. Nota sulle produzioni di ceramica a decorazione sovradipinta e sulla coroplastica ellenistica a Messina. In Da Zancle a Messina. Un Percorso Archeologico Attraverso Gli Scavi; Bacci, M.G., Tigano, G., Eds.; Regione siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e Ambientali e della Pubblica Istruzione: Messina, Italy, 2002; Volume II, pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Spigo, U. Rinvenimenti di ceramica siceliota dalla provincia di Messina: Breve nota di aggiornamento. In Studi Classici in Onore di Luigi Bernabò Brea; Bacci, G.M., Martinelli, M.C., Eds.; Regione Siciliana—Museo Archeologico Regionale Eoliano “Luigi Bernabò Brea”: Messina, Italy, 2003; pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Tigano, G. Isolato S, Via Industriale. Lo scavo e i primi dati sui materiali. In Da Zancle a Messina. Un Percorso Archeologico Attraverso gli Scavi; Bacci, M.G., Tigano, G., Eds.; Regione siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e Ambientali: Messina, Italy, 1999; Volume I, pp. 123–155. [Google Scholar]

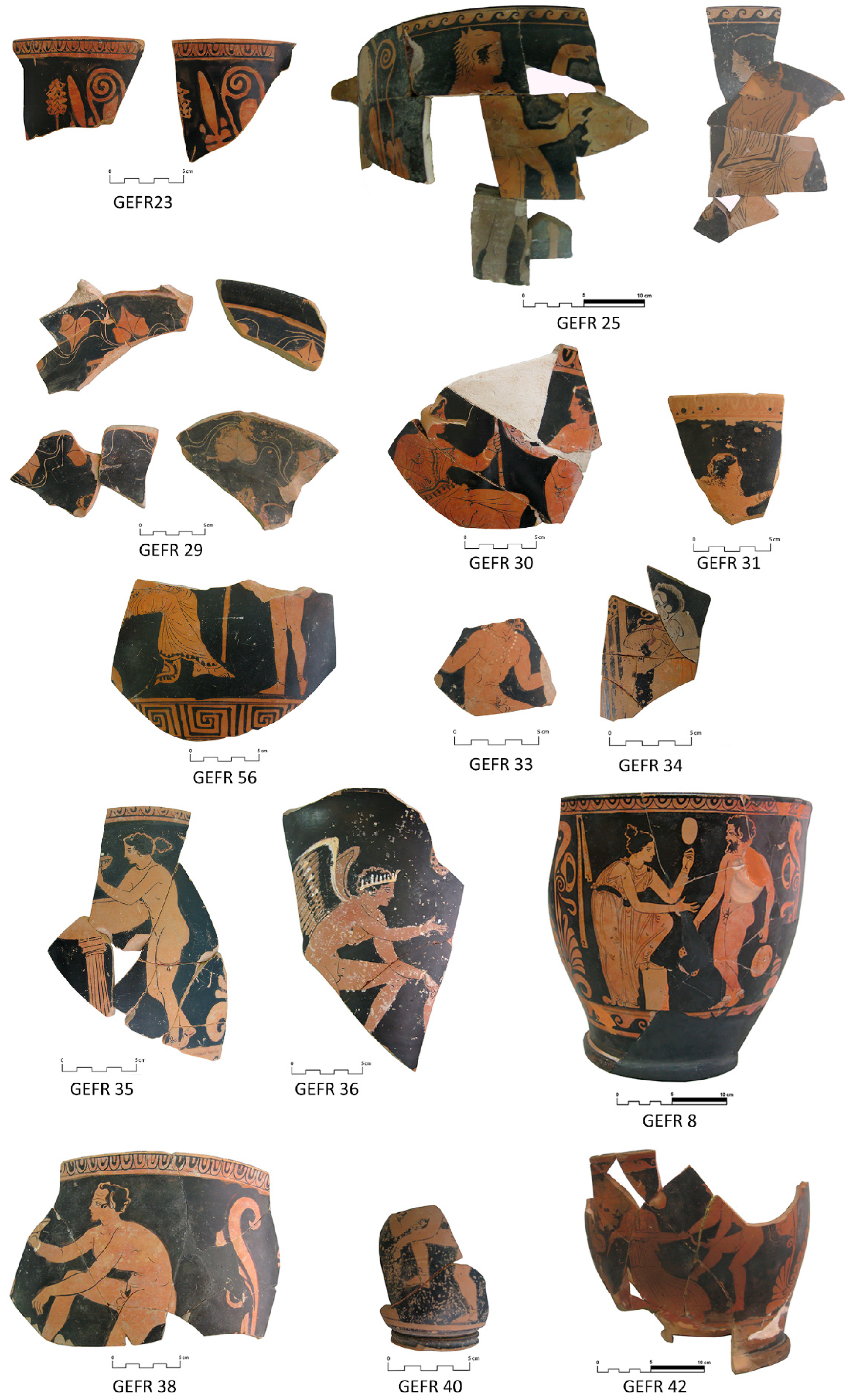

| Sample ID | Attribution | Type and Chronology | Provenance | Munsell Colour |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEFR 23 (no inv.) | Chequer Painter [1] (p. 199), n. 17 | Skyphos (fr.) Late 5th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento, (excavation 1953) | M 7.5YR 6/6 (reddish yellow) |

| GEFR 25 (no inv.) | Locri Group [49] | Skyphos (fr) Late 5th-early 4th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1973–74) | M 5YR 5/6 (yellowish red); M 5YR 6/4 (light reddish brown); M 7.5YR 5/3 (brown) |

| GEFR 30 (no inv.) | Dirce Painter [3] (p. 26), n. 12 | Skyphos (fr.) Early 4th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1953) | M 7.5YR 6/6 (reddish yellow) |

| GEFR 29 (no inv.) | Dirce Group (unpublished) | Calyx-krater (fr.) Early 4th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1973) | M 7.5YR 6/3 (light brown) |

| GEFR 56 (no inv.) | Dirce Group (unpublished) | Bell-krater (fr.) Early 4th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1955) | M 5YR 6/8 (reddish yellow) |

| GEFR 31 (no inv.) | Dirce Group (unpublished) | Skyphos (fr.) Early 4th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1973) | M 7.5YR 6/6 (reddish yellow) |

| GEFR 33 (no inv.) | Painter of Louvre K 240 (unpublished) | Krater? (fr.) End of first 4th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1973) | M 5YR 5/4 (reddish brown) |

| GEFR 34 (no inv.) | Painter of Louvre K 240 or Asteas (new attribution) | Krater? (fr.) End of first 4th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1973) | M 7.5YR 6/4 (light brown) |

| GEFR 35 (no inv.) | Lentini Painter (unpublished) | Skyphos (fr.) First quarter 4th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1973) | M 7.5YR 6/6 (reddish yellow) |

| GEFR 36 (no inv.) | Lentini Painter (unpublished) | Skyphos (fr.) First quarter 4th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1973) | M 7.5YR 6/3 (light brown) |

| GEFR 8 (inv. 8565) | Rancate Group [1] (p. 591), n. 37, Table 229, 6 | Skyphos (fr.) Second quarter 4th cent. B.C. | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1953) | M 5YR 6/6 (reddish yellow) |

| GEFR 38 (no inv.) | Rancate Group (unpublished) | Skyphos (fr.) Second quarter 4th cent. B.C | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1973) | M 5YR 6/6 (reddish yellow) |

| GEFR 40 (no inv.) | Rancate Group (unpublished) | Squat lekythos (fr.) Second quarter 4th cent. B.C | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1953) | M 5YR 6/6 (reddish yellow) |

| GEFR 42 (no inv.) | Not attributed | Skyphos (fr.) Second quarter 4th cent. B.C. (?) | Gela. Molino a Vento (excavation 1973–74) | M 7.5YR 5/4 (brown) |

| Attribution | Sample ID | SiO2 | TiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | P2O5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chequer Painter | GEFR_23 | 53.1 | 0.8 | 23.3 | 8.3 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 6.3 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 0.2 |

| Locri Group | GEFR_25 | 53.8 | 0.8 | 22.2 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 0.2 |

| Dirce Group | GEFR_29 | 55.1 | 1.1 | 23.7 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 4.6 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 0.2 |

| Dirce Painter | GEFR_30 | 53.2 | 0.8 | 23.3 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 6.3 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 0.2 |

| Dirce Group | GEFR_31 | 54.1 | 0.8 | 22.3 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 6.4 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 0.1 |

| Dirce Group | GEFR_56 | 53.6 | 0.8 | 22.9 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 0.1 |

| Painter of Louvre K 240 | GEFR_33 | 55.3 | 0.8 | 21.7 | 8.3 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 6.2 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 0.2 |

| Painter of Louvre K 240 or Asteas | GEFR_34 | 57.9 | 0.8 | 20.6 | 7.7 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 5.8 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 0.2 |

| Lentini Painter | GEFR_35 | 54.7 | 0.8 | 22.8 | 8.4 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 5.2 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 0.2 |

| Lentini Painter | GEFR_36 | 56.5 | 0.9 | 20.9 | 7.9 | 0.1 | 2.7 | 6.4 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 0.2 |

| Rancate Group | GEFR_8 | 56.2 | 1.0 | 23.2 | 6.3 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 0.1 |

| Rancate Group | GEFR_38 | 54.2 | 1.0 | 22.1 | 7.4 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 8.2 | 0.9 | 3.0 | 0.2 |

| Rancate Group | GEFR_40 | 56.9 | 0.9 | 20.6 | 8.0 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 6.1 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 0.2 |

| Not attributed | GEFR_42 | 56.2 | 0.7 | 20.4 | 7.8 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 7.2 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 0.1 |

| Attribution | Sample ID | Ba | Ce | Cr | Ni | Pb | Rb | Sn | Sr | Y | Zn | Zr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chequer Painter | GEFR_23 | 623 | 83 | 123 | 47 | 58 | 158 | 13 | 351 | 34 | 160 | 196 |

| Locri Group | GEFR_25 | 447 | 86 | 129 | 55 | 176 | 163 | 11 | 358 | 32 | 159 | 186 |

| Dirce Group | GEFR_29 | 625 | 63 | 129 | 45 | 33 | 155 | 15 | 323 | 39 | 127 | 266 |

| Dirce Painter | GEFR_30 | 624 | 72 | 121 | 46 | 56 | 146 | 20 | 319 | 39 | 154 | 192 |

| Dirce Group | GEFR_31 | 586 | 109 | 125 | 49 | 36 | 157 | 15 | 332 | 35 | 145 | 199 |

| Dirce Group | GEFR_56 | 692 | 87 | 118 | 48 | 51 | 156 | 18 | 346 | 35 | 151 | 205 |

| Painter of Louvre K 240 | GEFR_33 | 547 | 100 | 126 | 42 | 62 | 155 | 13 | 291 | 38 | 141 | 246 |

| Painter of Louvre K 240 or Asteas | GEFR_34 | 515 | 47 | 124 | 39 | 48 | 104 | 24 | 218 | 37 | 119 | 213 |

| Lentini Painter | GEFR_35 | 639 | 102 | 132 | 46 | 54 | 164 | 14 | 279 | 40 | 144 | 237 |

| Lentini Painter | GEFR_36 | 537 | 84 | 120 | 40 | 65 | 142 | 13 | 340 | 36 | 126 | 248 |

| Rancate Group | GEFR_8 | 993 | 117 | 118 | 50 | 46 | 192 | 14 | 277 | 35 | 110 | 221 |

| Rancate Group | GEFR_38 | 682 | 85 | 127 | 42 | 41 | 140 | 14 | 482 | 33 | 111 | 202 |

| Rancate Group | GEFR_40 | 509 | 82 | 126 | 41 | 43 | 140 | 17 | 303 | 41 | 133 | 258 |

| Not attributed | GEFR_42 | 541 | 104 | 115 | 37 | 64 | 150 | 11 | 298 | 31 | 127 | 261 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santostefano, A.; Barone, G.; Mazzoleni, P.; Miriello, D.; Raneri, S. Chemical Investigation of Sicilian Red-Figure Pottery: Provenance Hypothesis on Vases from Gela (Italy). Heritage 2025, 8, 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120505

Santostefano A, Barone G, Mazzoleni P, Miriello D, Raneri S. Chemical Investigation of Sicilian Red-Figure Pottery: Provenance Hypothesis on Vases from Gela (Italy). Heritage. 2025; 8(12):505. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120505

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantostefano, Antonella, Germana Barone, Paolo Mazzoleni, Domenico Miriello, and Simona Raneri. 2025. "Chemical Investigation of Sicilian Red-Figure Pottery: Provenance Hypothesis on Vases from Gela (Italy)" Heritage 8, no. 12: 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120505

APA StyleSantostefano, A., Barone, G., Mazzoleni, P., Miriello, D., & Raneri, S. (2025). Chemical Investigation of Sicilian Red-Figure Pottery: Provenance Hypothesis on Vases from Gela (Italy). Heritage, 8(12), 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120505