Abstract

This paper presents the results of a multidisciplinary research project carried out over the past two years by the Archaeological Mapping Laboratory at the CNR-ISPC, Lecce, and the Heritage Materials Science group at the CNR-ISPC, Florence, in collaboration with the PASAP Med Ph.D. Programme at the University of Bari “Aldo Moro”. The investigation focuses on stone procurement strategies employed by the Messapian settlement at Ugento, near the Ionian coast of Salento. Archaeological surveys within its territory and surrounding areas enabled the identification and petrographic characterization of ancient extraction sites, allowing for the classification of several calcarenite types. Systematic sampling and petrographic analyses of archaeological specimens shed light on the sourcing strategies adopted for both the construction of the city’s defensive walls—erected in the mid-4th century BCE—and selected architectural and sculptural elements preserved in the Ugento Archaeological Museum and the Colosso Collection, dating from the Archaic to the Hellenistic periods. The analyses show that the availability of lithotypes in the region significantly influenced construction techniques, particularly in the city walls, while in certain cases—such as specific architectural elements made of pietra leccese—it required the import of lithologies absent from the immediate vicinity.

1. Introduction

A multidisciplinary research project conducted over the past two years by the Archaeological Mapping Laboratory in Lecce and the Heritage Materials Science Laboratory in Florence, both part of the Institute of Heritage Sciences of the Italian National Research Council (ISPC-CNR), in collaboration with the PhD programme in Mediterranean Archaeological, Historical, Architectural and Landscape Heritage at the University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, has examined how Messapian communities managed local stone resources. In particular, the study examines how these resources were used to supply the large-scale city-wall construction, in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE characterized the urban landscape of these settlements. Research has highlighted not only their defensive purposes but also their ideological, cultural, political, and self-representational significance for the communities that built them [1,2].

Among the Messapian settlements investigated, a particular case study was conducted in Ugento, in southwestern Salento. The settlement developed from the late Iron Age (8th–7th centuries BCE) and acquired urban characteristics as early as the Archaic period (6th century BCE). Around the mid-4th century BCE, Ugento was enclosed by an impressive fortification circuit, extending for approximately 4.900 m and covering c. 145 hectares. Archaeological excavations have revealed that the defensive system was constructed in at least two distinct phases, identified through the recovery of stratigraphic evidence [3,4] (pp. 424–429); [5] (pp. 251–252, 346–361); [6] (pp. 239–261); [7,8] (pp. 81–102) [9].

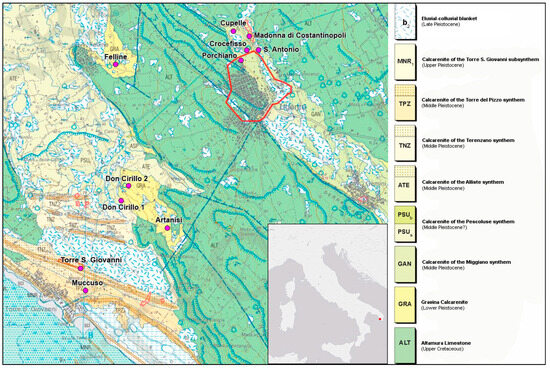

In the first phase, the defensive perimeter in the western sector (Figure 1) was built on very hard Upper Cretaceous limestones, known as Altamura Limestone [10] (pp. 31–35), which are difficult to work. The wall is 4.60 m thick at Cupa and 5.80–6.10 m at Via Tasso. It consisted of two outer faces made of parallelepiped calcarenite blocks (a soft, versatile stone that outcrops in the urban area; see below) enclosing a core fill of limestone rubble and soil. On the inner face, the blocks were laid longitudinally, while on the outer face, they were arranged in alternating courses of headers and stretchers. Representative block sizes are as follows: length approx. 150 cm, width 60–73 cm, height 48–50 cm—Cupa; length 115–165 cm, width 60–75 cm, height 35–47 cm—Via Tasso (Figure 2A, 1). The eastern section of the wall was built on extensive outcrops of calcarenite, mostly belonging to the so-called Miggiano Synthem and partly to the Gravina Calcarenite [10] (pp. 41–44, 47–49, 86). In this sector, the wall appears to have been entirely constructed in opus quadratum for its whole width, varying between 2.50 m at S. Antonio and 3.40 m at Armino (representative block sizes: length 155–170 cm, width 70–75 cm, height 40–50 cm—S. Antonio; length 165–170 cm, width 75–80 cm, height 45 cm—Armino).

Figure 1.

Map of Ugento, showing the georeferenced city wall and the remains of the ditch; sampling areas (yellow dots) and the different types of outcrops are indicated (ALT = Altamura Limestone; GAN = calcarenites of the so-called Miggiano Synthem; GRA = Gravina Calcarenites; PSU = clayey sands of the so-called Pescoluse Synthem overlying the calcarenites).

Figure 2.

Messapic city wall: above (A), stretch exposed in Via Tasso showing the first (1) and second (2) construction phases; below, at Cupa, external (B) and internal (C) facing of the second phase.

In a second construction phase, probably at the end of the 4th–early 3rd century BCE, the wall was reinforced with an additional external facing. This new facing measured approximately 1.55 m at Cupa (Figure 2B), 1.70 m at Via Tasso (Figure 2A, 2), and 3.50 m at S. Antonio. It was built with considerable care, using relatively uniform calcarenite blocks laid in alternating courses of headers and stretchers (representative block sizes: length approx. 150–170 cm, width 75–80 cm, height 48–52 cm—Cupa; length 160 cm, width 70 cm, height 35 cm—Via Tasso; length 155–170 cm, width 70–75 cm, height 40–50 cm—S. Antonio). In the same phase or shortly after (still within the 3rd century BCE), some sections originally built with a double-faced and emplekton (as at Cupa) received an additional inner facing, consisting of blocks laid longitudinally. This facing, however, was irregular, combining parallelepiped calcarenite blocks with large unshaped limestone blocks removed from the bedrock along natural fracture lines (Figure 2C). As a result of these additions, the total wall thickness increased, reaching approximately 6 m at S. Antonio, 7 m at Cupa, and 8 m at Via Tasso.

Archaeological surveys in the Ugento area documented ancient stone quarries used to extract several types of calcarenite. Systematic sampling and minero-petrographic analysis of numerous quarries and archaeological specimens made it possible to link the specimens to their likely sources, with appropriate caution, given the variability of sedimentary rocks even within the same quarry. These data made it possible to identify different procurement strategies for the blocks used in the construction of the walls across their phases, as already suggested in a preliminary study [11], highlighting how the local availability of lithotypes influenced construction techniques.

Furthermore, the same quarry sample database was used to determine the provenance of stone materials employed for architectural and sculptural elements dating from the Archaic to the Hellenistic period, found in cultic, funerary, and public or private contexts. This study revealed several practices adopted by the Messapian communities, including the selection of specific local lithotypes and the importation of a particular stone not locally available (so-called pietra leccese), which was particularly suitable for sculptural objects.

This case study engages with key methodological debates in stone-provenance archaeology by integrating stratigraphic excavation, fieldwork surveys, GIS-based sampling, and mineralogical–petrographic analysis. Methodologically, it complements established approaches in the provenance study of high-value lithologies such as marble, extending the application of multi-method, spatially explicit protocols to calcarenite deposits. By systematically connecting geological outcrops to archaeological contexts, it offers a replicable framework that responds to current calls for transparent provenance protocols—strengthening the link between material sourcing and broader patterns of landscape use.

2. Materials and Methods

To characterize the strategies for the exploitation of stone resources in the Ugento area during the Messapian period, an extensive survey and sampling campaign were conducted. Quarry sites were initially identified through an initial review of satellite imagery and historical aerial photographs and then verified in the field. Each quarry was archaeologically documented using GPS and drone surveys. All data were managed within a dedicated GIS project. This included georeferenced geological maps, historical aerial photographs, quarry locations, sampling points, and photographic documentation. For each sampling point, the GIS includes an attribute table recording the corresponding minero-petrographic information of the sample. Samples were collected both from ancient calcarenite quarries identified during archaeological surveys (Table 1) and from archaeological artefacts, including the Messapian wall blocks (Table 2) and a selection of architectural materials dating from the 6th to the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE (Table 3). Sampling was carried out using a minimally invasive approach and followed a well-established analytical protocol. This included full mineralogical and petrographic characterization through X-ray diffraction (XRD) and thin-section analysis under a polarised light microscope. Field sampling was performed by the Archaeological Mapping Laboratory at CNR-ISPC, Lecce, while laboratory analyses were carried out at the Heritage Materials Science Laboratory at CNR-ISPC, Florence.

Table 1.

Samples collected from calcarenite quarries in the Ugento area.

Table 2.

Samples collected from stretches of the Messapian city walls of Ugento.

Table 3.

Selected architectural and sculptural artefacts from Ugento.

A preliminary analysis of mineralogical composition was performed using a PANalytical X’Pert Pro X-ray diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, United Kingdom) under the following conditions: Cu Kα1 radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), X-ray tube settings 40 kV and 30 mA, angular range 3° < 2θ < 70°, step size 0.02°. For phase identification of XRPD results, the Powder Diffraction (PDF) database from the International Center for Diffraction Data (ICCD) was used. For petrographic characterization, samples were embedded in Epofix resin and reduced to 30 μm thick sections and examined with an Axioscope A.1 optical microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) under reflected and transmitted light, equipped with a high-resolution camera and Axiovision software (V1) for image management and morphometric analysis.

Quarry samples were analysed to create a reference database for the provenance of lithotypes used for the wall blocks, as well as for architectural and sculptural artefacts. The number of samples per site varied with site size, state of preservation, and access to ancient quarry faces (Table 1). The sampling strategy involved collecting wall samples from all preserved sections, ensuring a systematic spatial distribution across the visible stretches. Particular attention was given to the long segments exposed during recent archaeological excavations. Sampling targeted areas showing distinct construction features, focusing on both inner and outer facings and on the different building phases, in order to obtain representative samples of the entire structure (Table 2). Finally, sampling was extended to selected architectural elements preserved in the Archaeological Museum and in the Colosso Collection (Table 3). These artefacts, dating from the Archaic to the Hellenistic periods, were made from blocks identified macroscopically as calcarenite and pietra leccese (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The study also aimed to evaluate the selection of different types of calcarenite compared to those used for the defensive walls.

Figure 3.

Ugento, sculptural and architectural materials in calcarenite: (A) semi-chamber of the Athlete’s Tomb; (B,C) fragments of Doric frieze from Via Monsignor de Razza; (D) capital from Via Messapica; (E) fragment of Doric frieze with Messapian inscription from Colonne; (F) altar with Doric frieze from Via Urso; (G) block with Messapian inscription from Ex Convento dei Frati Minori Osservanti; (H) altar with Messapian inscription; (I) block with Messapian inscription from Fondo Chiesaredda.

Figure 4.

Ugento, sculptural and architectural materials in pietra leccese: (A) Doric capital with abacus decorated with relief rosettes from Colonne; (B) sofa-shaped capital from Colonne; (C) fragment of cornice with Messapian inscription; (D) fragmentary female statuette; (E) juvenile male head.

Minero-petrographic data were used to hypothesize stone provenance from quarries based on key parameters such as mineralogical composition and petrographic classification of carbonate rocks. The study applied a two-step classification approach combining Dunham and Folk criteria: the Dunham scheme was first used to assign each sample to a main class (e.g., mudstone, wackestone, packstone, grainstone), focusing on depositional texture and the presence, abundance, and support of grains or mud. Subsequently, the Folk classification refined the analysis by specifying the relative proportions and types of carbonate components, as well as a detailed characterization of the micritic matrix and sparry calcite cement. This integrated approach provided a comprehensive petrographic framework for provenance analysis.

Diagnostic features used to distinguish quarry sources included texture classification (packstone, grainstone, wackestone, mudstone), typeand abundance of typical fossil assemblages (benthic foraminifera, corals, bivalve fragments, echinoids, sponge spicules, bryozoans), and grain size distributions observed in thin sections. Additionally, the degree and nature of carbonate cementation (notably microsparitic cement), types and abundance of porosity (intergranular and intragranular, with attention to pore morphology), and accessory minerals such as clay minerals, quartz, and iron oxides influencing colour were carefully considered. These combined minero-petrographic criteria formed a robust basis for differentiating calcarenite deposits from distinct quarry districts and underpinned the reliable attribution of stone provenance presented in this study.

A complete presentation of the mineralogical–petrographic dataset and classification workflow is being prepared in a separate paper; here, we provide a targeted summary sufficient to support the provenance interpretations reported in this study.

3. Results

Archaeological surveys have documented all known, preserved ancient quarry sites in the Ugento area, exploited for different types of calcarenite [15] (Figure 5). The evidence suggests that, in the Messapian period, the choice of extraction sites was primarily determined by local geological conditions. Where calcarenite outcrops occur, quarries are generally located in sectors where the deposit reaches its maximum thickness, as confirmed by geological studies [10].

Figure 5.

Geological map of the Ugento area (after Ricchetti, Ciaranfi, 2013 [10]), showing the georeferenced line of the city wall and quarries opened on outcrops of different types of calcarenite.

A substantial cluster of quarries, partly destroyed by modern quarrying, extends immediately north of the 4th–3rd century BCE urban area, in the localities of S. Antonio, Crocefisso, Madonna di Costantinopoli, and Cupelle (Figure 6). These quarries mainly supplied calcarenite from the Miggiano Synthem, which outcrops in these areas with considerable thickness. From a petrographic perspective, the extracted stone can be classified as grain-supported packstone/grainstone, showing a variable ratio between carbonate mud and microsparitic carbonate cement [16]. The fossil component ranges in size from 1 to 3–4 mm [11] (Figure 7A–C). Sampling from the preserved sections of the city walls showed that nearby portions of the northeastern sector of the defensive circuit were built with blocks extracted from these quarries. The same quarry complex was also exploited during the second construction phase in the western sector (Cupa and Via Tasso: cf. Figure 7A–C and Figure 8A). However, these later blocks differ in both texture and fossil assemblage from those of the first construction phase identified in the same area (cf. Figure 8A,B). They also appear more compact in macroscopic terms.

Figure 6.

Calcarenite quarry face at Cupelle.

Figure 7.

Polarised light microscope images of samples from calcarenite quarries in the Ugento area (crossed nicols): (A) Cupelle; (B) Madonna di Costantinopoli; (C) S. Antonio; (D) ditch; (E) Felline; (F) Don Cirillo 2; (G) Artanisi; (H) Torre S. Giovanni; (I) Muccuso.

Figure 8.

Polarised light microscope images of samples from calcarenite blocks of the Messapic walls and from architectural and sculptural materials in calcarenite and pietra leccese preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Ugento and the Colosso Collection (crossed nicols): (A) wall block from Cupa, outer face, 2nd phase; (B) wall block from Cupa, outer face, 1st phase; (C) wall block from Armino; (D) block from the Athlete’s Tomb; (E) block with Messapic inscription from Ex Convento dei Frati Minori Osservanti; (F) altar with Messapic inscription, Colosso Collection; (G) Doric frieze with Messapic inscription from Colonne; (H) block with Messapian inscription from Fondo Chiesaredda; (I) Fragment of a Doric frieze with Messapian inscription from Via Monsignor de Razza; (J) fragment of cornice with Messapian inscription; (K) fragmentary female statuette; (L) sofa-shaped capital.

The provenance of the calcarenite used in the earliest phase of the western sector remains uncertain. It cannot be ruled out that the material originated from the northern —possibly from superficial levels no longer recognisable—or from other extraction sites that are no longer identifiable. Minor differences have also been observed in blocks from the southernmost part of the eastern side (Armino). These blocks belong to a lithotype still classified as packstone/grainstone, closely resembling the material found in the ditch located approximately 25 m outside the fortifications on this side [9] (pp. 17–20) (cf. Figure 7D and Figure 8C). The ditch, still partially visible at Santisorgi and briefly exposed at Santisorgi/Aia, varies in width from 3.65–4 m to about 7 m, with a depth between 1.10 and 1.20 m (see Figure 1 above). It has been documented along most of the eastern wall and in the easternmost part of the southern section, in areas where calcarenite outcrops are relatively shallow. In these zones, the excavation stopped on the underlying hard limestone layers, forming a shallow trench. In many areas, clear traces of block extraction show that the ditch itself also served as a quarry.

Further archaeological surveys identified additional ancient extraction areas—partly exploited in modern times—located farther from the Messapian urban area. These quarries extracted stone from extensive outcrops of the Gravina Calcarenite. One large quarry lies just over 2 km west of the settlement, on the eastern outskirts of Felline. Another extensive site, Don Cirillo 2, is located approximately 2.5 km southwest of Ugento (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Calcarenite quarry at Don Cirillo: oblique drone view (A) and plan view (B).

Smaller extraction sites are located a few dozen meters southwest (Don Cirillo 1) and about 1 km southeast (Artanisi). Petrographic analyses indicate that the lithotype from Felline can be classified as packstone/grainstone. In contrast, the Don Cirillo 1–2 and Artanisi sites yielded packstone/wackestone with a lower degree of cementation (Figure 7E–G). This latter variety shows some similarities with the blocks from the first construction phase of the walls at Via Tasso and Cupa, i.e., in the western and southwestern sectors. However, these similarities are not sufficient at this stage to suggest that these quarries, particularly Don Cirillo 2, were exploited during the earliest phase of the fortification. Despite the extent of these quarries (especially Felline and Don Cirillo 2), no archaeological materials have yet been directly linked to these quarry sites.

Two additional major quarries were identified further southwest, just north of Torre S. Giovanni and the Ionian coast, approximately 4.5 km from Ugento. These sites exploited outcrops of calcarenite belonging to the Terenzano Synthem (so-called Torre S. Giovanni Nuova quarry) and to the Torre del Pizzo Synthem (Muccuso quarry), both dated to the Middle Pleistocene [10] (pp. 53–56). The first site, which has been extensively exploited in modern times, still preserves traces of earlier extraction along its southwestern sector (Figure 10). The second quarry is largely buried but is clearly visible in 1943 aerial photographs taken by the Italian Military Geographic Institute. A small portion was discovered in 2022 during archaeological excavations for public road construction (Figure 11). Petrographic analysis shows that the lithotypes from these two quarries, located only a few hundred meters apart, are very similar. They can be classified as grainstone showing variable degrees of cementation and grain size (Figure 7H–I).

Figure 10.

Calcarenite quarry at Torre San Giovanni: oblique drone view (A) and plan view (B).

Figure 11.

The quarry at Muccuso was exposed in 2022.

The lithotype from these two quarries closely aligns with the calcarenite used in several architectural elements found in Ugento and now preserved in the Archaeological Museum and the Colosso Collection. All these artefacts are classified as grainstone with carbonate cement (cf. Figure 7H and Figure 8D; Figure 7I and Figure 8E–I). Some of these date to the Archaic period, such as the slabs forming the large semi-camera of the so-called Tomb of the Athlete (late 6th–early 5th century BCE; Table 3, No. 1; Figure 3A and Figure 8D). This evidence indicates that these quarries were already exploited at an early date. Most of the artefacts, however, belong to the Hellenistic period. These include a Doric capital (Table 3, No. 2; Figure 3D) from Via Messapica (4th–3rd century BCE); a fragment of a Doric frieze with Messapian inscription (Table 3, No. 3; Figure 3E and Figure 8G) from Colonne (3rd century BCE); two Doric frieze fragments from Via Monsignor de Razza (Table 3, Nos. 3–4; Figure 3B–C and Figure 8I), one with a Messapian inscription (3rd century BCE); a decorated Doric altar (Table 3, No. 6; Figure 3F) from Via Urso (Hellenistic period); another altar without frieze and of uncertain provenance with Messapian inscription (Table 3, No. 7; late 3rd–2nd century BCE); a block (Table 3, No. 8; Figure 3I) with Messapian inscription (3rd–2nd century BCE) from Fondo Chiesaredda; and a further block with an inscription (Table 3, No. 9; Figure 3G) from the garden of the Ex Convento dei Frati Minori Osservanti (late 3rd–2nd century BCE) [13].

Other architectural and, especially, sculptural elements were made of a lithotype known as pietra leccese, which does not occur in Ugento but is typical of central Salento (including Lecce, Corigliano d’Otranto, Melpignano, Cursi, and Maglie). This fine-grained pale yellow-white biocalcarenite is composed almost entirely of microfossils (planktonic foraminifera) [17,18,19]. The examined samples are notably homogeneous. Petrographically, they are classified as wackestone with abundant carbonate matrix containing finely dispersed clay minerals. Small amounts of microcrystalline calcite, together with minor iron oxides and glauconite fragments, are also present. Due to its fine texture and ease of carving, this stone was particularly suitable for elaborate sculptural decorations in low or high relief. Some of the earliest examples from Ugento belong to the Archaic period.

Examples include a Doric capital (Table 3, No. 10; Figure 4A) with an abacus decorated on all sides with three raised rosettes and a small sofa capital (Table 3, No. 11; Figure 4B and Figure 8L), both from Colonne and preserved in the Colosso Collection. The same collection also houses a small pietra leccese stele (width 27 cm, height 60 cm, thickness 8 cm) with a cavetto cornice (39 × 8 cm, height 11 cm) [8] (p. 59), dated to the second half of the 6th century BCE. This Doric capital closely resembles another example (72.8 × 72.8 cm, height 23 cm) that once supported the famous bronze statue of Zeus (530–500 BCE) now at the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto [20]. Although it could not be sampled, it is macroscopically very similar to the Colosso capital and is likewise made of pietra leccese.

There are also numerous examples of sculptural artefacts made of pietra leccese. These include a fragmentary female figurine (Table 3, No. 12; Figure 4D and Figure 8K), likely originating from a prestigious burial, carved in a more cemented and compact variety of the stone, and a small juvenile male head (Table 3, No. 13; Figure 4E), likely part of a tomb decoration. Both are dated to the 4th–3rd century BCE and are preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Ugento [14]. The museum also houses a frame with a 3rd–century BCE Messapian inscription from an unknown public building (Table 3, No. 14; Figure 4C and Figure 8J). This artefact is made of a very fine-grained stone. A small temple model (width 10 cm, height 17 cm, thickness 3.2 cm) depicts Aphrodite and Eros in high relief (3rd century BCE) [14], also of uncertain provenance, and is macroscopically similar in fabric to the juvenile head. Finally, other high-quality sculptures—although not sampled—appear to be made of a very similar variety of pietra leccese. These include a small male head (ca. 15 cm) from the Colosso Collection (late 4th–early 3rd century BCE) [21] and a sema base (width 63 cm at bottom, 49 cm at top, height 54 cm) decorated with cavalry and hoplite battle scenes from Via Monterotto (late 4th–early 3rd century BCE), now in the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto [22].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The recent effort to reconstruct procurement strategies for the large-scale construction of the Messapian city walls of Ugento shows a careful selection of available stone materials and a strong influence of the geological characteristics of the substrate on both construction choices and building techniques [9] (pp. 19–20). The approaches adopted along the extensive defensive circuit appear strongly influenced by the bedrock type and the locally accessible lithic resources.

In the western sector of the defensive perimeter, built on Upper Cretaceous carbonate rocks belonging to the Altamura Limestone—a very compact, grey-white, extremely hard and difficult-to-work limestone—the wall was constructed with two faces of parallelepiped calcarenite blocks containing a core of limestone rubble and soil. This technique minimized the number of blocks that needed to be transported from distant quarries and allowed the use of locally available stone for the emplekton (even though it could not be shaped into regular blocks). In contrast, the eastern portion of the walls, built on softer and easier-to-work Pleistocene calcarenite, was entirely constructed of ashlar throughout its width, taking full advantage of the abundant workable stone available as blocks.

A similar selectivity is evident in the second construction phase. The outer wall added to strengthen the fortifications, designed to resist enemy assaults and siege engines, was built from well-dressed, squared blocks, carved from calcarenite quarries located immediately north of the city. The new inner wall, added to the older structure in some sectors of the western portion, was built instead using highly irregular masonry, combining parallelepiped calcarenite blocks and roughly shaped limestone blocks, extracted locally along natural fracture lines.

Ugento lay within a territory with abundant, readily accessible stone suitable for a large-scale building program, likely involving sustained local labour over several decades during the 4th–3rd centuries BCE. The first city wall phase exhibits more diverse quarry sources, indicating complex logistics and perhaps less centralized management. By contrast, the second phase shows a more focused procurement strategy, with most blocks sourced consistently from quarries to the north and east of the city, reflecting a streamlined, efficiently coordinated supply chain. The northern quarries were intensively exploited, yielding a soft, easily worked stone of moderate quality. While unsuitable for architectural elements, this stone was ideal for producing large parallelepiped blocks, and its moderate density combined with quarry proximity facilitated transport.

The architectural and sculptural artefacts examined likewise reflect a targeted selection of lithotypes available in the Ugento area, where several workable calcarenite units were accessible. Less compact stones with a carbonate-mud-rich matrix—with lower mechanical strength—were employed in the Hellenistic walls. More compact and well-cemented calcarenites, available a few kilometres from the settlement near the coastal area of Torre San Giovanni (Muccuso), were already selected during the Archaic period for architectural and structural elements of civic, sacred, and funerary buildings.

From at least the second half of the 6th century BCE—and especially in the 4th–3rd centuries BCE—more elaborate sculptural artefacts were made in pietra leccese. This lithotype, absent in the Ugento area and the surrounding district [23] (Figure 1), was already known to local workshops in the Archaic period for its homogeneous fine grain, softness, and ease of carving, making it particularly suitable for complex low-relief decorations and statuary. Consequently, the stone appears to have been imported from other areas. The nearest potential source is the Maglie district, located c. 25 km away, within the territory of the major Messapian centre of Muro Leccese. Blocks could have reached Ugento by cart along inland routes, or by sea from the Adriatic coast to the port of Torre San Giovanni, ensuring a steady supply for local workshops. Moreover, many pietra leccese artefacts in Ugento, especially those dating to the 4th–3rd centuries BCE, show a clear influence from contemporary Tarentine sculpture. It is therefore possible that some were produced locally by itinerant artisans from the Laconian colony who were skilled in working this stone [24] (p. 141); [25] (p. 157), while others may have arrived as finished imports via commercial channels. Future sampling and comparison with the main pietra leccese quarries may help to clarify the provenance of the stone used for Ugento artefacts. The destination of the numerous blocks extracted from the large quarries at Felline and the Don Cirillo–Artanisi area remains uncertain. These quarries generally yielded small blocks—likely in medieval and early modern phases—although traces of larger block extraction are clearly visible, particularly at Don Cirillo 2. It is reasonable to suppose that the Felline quarry supplied the nearby settlement, which developed mainly in the medieval period but still preserves some late Republican and early imperial buildings [26] (pp. 152–154, nos. 171–172 and 176). However, it cannot be excluded that the Don Cirillo–Artanisi area was exploited for Ugento, only 2–3 km away from the Messapian centre. This high-quality calcarenite could have been used for archaeological artefacts not yet sampled, or its exploitation might have begun in Roman or medieval times. Therefore, a promising direction for future research will be to expand both the number and chronological range of sampled archaeological artefacts to better define the intended use of blocks from these extensive quarries.

In conclusion, this study has clarified several key aspects of stone procurement and use in the construction and architectural production of Ugento. Based on petrographic analyses of the collected samples, 100% of the blocks from the second construction phase of the fortifications can be securely attributed to the northern quarry district and to the eastern ditch located immediately outside the walls. Similarly, blocks from the northern and eastern sectors of the first construction phase derive from these same sources. A partial correspondence (approximately 30%) was observed between the first phase blocks from Cupa and Via Tasso and the Don Cirillo quarries.

All architectural calcarenite elements examined correspond fully to the coastal quarries near Torre San Giovanni and Muccuso. In contrast, no pietra leccese samples can currently be associated with a specific quarry (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of archaeological artefacts, construction phases, lithotypes, number of samples, corresponding quarries, and confidence levels for provenance assignments. High confidence in provenance assignments corresponds to samples showing a strong convergence of petrographic features—including typical fossil assemblages, cementation degree, and porosity types—with minimal internal variability within quarry sources. Medium confidence assignments are attributed where key features are still consistent but exhibit some variability or overlap with adjacent sources due to the natural heterogeneity of calcarenite deposits.

However, provenance assignments for the earliest construction phase—especially partial- or medium-confidence matches—remain limited by the natural heterogeneity of calcarenite formations. Subtle variations in texture, fossil assemblage, and degree of cementation within each quarry make absolute attribution challenging even with systematic sampling; conclusions regarding early-phase blocks are therefore presented with appropriate caution.

Future research will expand sampling of both quarries and archaeological materials to clarify the provenance of first-phase fortification blocks and pietra leccese artefacts, further refining our understanding of local supply networks and their implications for building and sculptural practices in Messapian Ugento.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.; methodology, G.S., N.D.B. and E.C.; minero-petrographic, E.C.; investigation, G.S. and N.D.B.; writing, G.S., N.D.B. and E.C.; writing—review and editing, N.D.B.; supervision, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lombardo, M. I Messapi: Aspetti della problematica storica. In I Messapi, Atti del 30° Convegno di Studi Sulla Magna Grecia; Pugliese Carratelli, G., Ed.; Institute for History: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 35–109. [Google Scholar]

- Grelle, F.; Silvestrini, M. La Puglia nel Mondo Romano. Storia di una Periferia. Dalle Guerre Sannitiche alla Guerra Sociale; Edipuglia: Bari, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzurro, A. Ugento. La cerchia delle mura messapiche (F. 223, IV, NE, Ugento). In Notiziario Topografico Salentino II. Contributi per la Carta Archeologica e per il Censimento dei Beni Culturali; Uggeri, G., Ed.; Museo Archeologico Provinciale “Francesco Ribezzo”: Brindisi, Italy, 1974; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Roller, D.W. Southern Messapia Survey 1992–1994: Preliminary Report; Studi di Antichità : Galatina, Italy, 1995; Volume 8, pp. 417–434. [Google Scholar]

- Lamboley, J.L. Recherches sur les Messapiens, IVe–IIe Siècle Avant J.–C.; Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises d’Athènes et de Rome: Rome, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzurro, A. Ozan. Ugento. Dalla Preistoria all’Età Romana; Edipuglia: Lecce, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scardozzi, G. La Cinta Muraria di Ugento; Edizioni Leucasia: Presicce, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Scardozzi, G. Carta Archeologica di Ugento. Topografia Antica e Popolamento Dalla Preistoria alla Tarda Antichità; Quatrini Edizioni: Viterbo, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scardozzi, G. Nuovi dati sulla cinta muraria messapica di Ugento: Caratteristiche costruttive e approvvigionamento del materiale lapideo. In ATTA; L’Erma di Bretschneider: Rome, Italy, 2024; Volume 34, pp. 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ricchetti, G.; Ciaranfi, N. Note Illustrative Della Carta Geologica d’Italia Alla Scala 1:50.000. Foglio 536 Ugento; Servizio Geologico d’Italia: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cantisani, E.; Di Benedetto, N.; Scardozzi, G. Indagini minero-petrografiche sulle mura messapiche e le cave di Ugento. In La Città Messapica di Ugento: Nuovi Dati dai Corredi Funerari del Museo Archeologico, Dalle Ricerche Sulla Cinta Muraria e Dalle Indagini di Archeologia Preventiva; Scardozzi, G., Ed.; Edizioni Esperidi: Monteroni di Lecce, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Porto, F.G. Tomba messapica di Ugento. In AttiMemMagnaGr; Atti e Memorie della Società Magna Grecia: Roma, Italy, 1971; pp. 99–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ismaelli, T. Materiali architettonici da Ugento. In Carta Archeologica di Ugento. Topografia Antica e Popolamento Dalla Preistoria Alla Tarda Antichità; Scardozzi, G., Ed.; Quatrini Edizioni: Viterbo, Italy, 2021; pp. 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Ismaelli, T.; Caggia, M.P. I materiali scultorei. In Il Nuovo Museo Archeologico di Ugento; Caggia, M.P., Scardozzi, G., Eds.; Edizioni Esperidi: Monteroni di Lecce, Italy, 2024; pp. 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Di Benedetto, N.; Scardozzi, G. Le cave antiche di Ugento. In La città Messapica di Ugento: Nuovi Dati dai Corredi Funerari del Museo Archeologico, Dalle Ricerche Sulla Cinta Muraria e Dalle Indagini di Archeologia Preventiva; Scardozzi, G., Ed.; Edizioni Esperidi: Monteroni di Lecce, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham, R.J. Classification of carbonate rocks according to depositional texture. In Classification of Carbonate Rocks; Ham, W.E., Ed.; Memories, 1; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1962; pp. 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Foresi, M.; Margiotta, S.; Salvatorini, G. Bio–cronostratigrafia a foraminiferi planctonici della Pietra leccese (Miocene) nell’area tipo di Cursi—Melpignano (Lecce, Puglia). Boll. Della Soc. Paleontol. Ital. 2002, 41, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Margiotta, S. Inquadramento geologico e territoriale della pietra leccese. Thalass. Salentina 2015, 37, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero, L. La pietra leccese. Thalass. Salentina 2015, 37, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andria, F. Colonne cippi e recinti sacri. In Klahoi Zis. Il culto di Zeus a Ugento; D’Andria, F., Dell’Aglio, A., Eds.; Moscara Associati: Cavallino, Italy, 2002; pp. 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, A. Sistema Museale Ugento. Nuovo Museo Archeologico; Scirocco Editore: Bari, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, L. Da Taranto alla Messapia. La base di un monumento funerario da Ugento fra immaginario eroico e realia. In Mitomania: Storie Ritrovate di Uomini ed Eroi; Degl’Innocenti, E., Consonni, A., Di Franco, L., Mancini, L., Eds.; Gangemi Editore: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andria, F. Pozzo Seccato nel sistema territoriale messapico del IV–III sec. a.C. In La Fattoria Messapica Fortificata di Pozzo Seccato (Acquarica di Lecce). Ricerche 1996–2024; D’Andria, F., Mannino, K., Notario, C., Eds.; Edizioni Esperidi: Monteroni di Lecce, Italy, 2024; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andria, F. Scultori greci e tarantini a Castro: Immagini di culto e offerte per Atena. In Athenaion. Tarantini, Messapi e Altri nel Santuario di Atena a Castro; D’Andria, F., Degl’Innocenti, E., Caggia, M.P., Ismaelli, T., Mancini, L., Eds.; Edipuglia: Bari, Italy, 2023; pp. 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ismaelli, T. I fregi con girali abitati di Castro. In Athenaion. Tarantini, Messapi e Altri nel Santuario di Atena a Castro; D’Andria, F., Degl’Innocenti, E., Caggia, M.P., Ismaelli, T., Mancini, L., Eds.; Edipuglia: Bari, Italy, 2023; pp. 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzulla, B. Carta Archeologica del Settore Sud-Occidentale della Penisola Salentina. Il Territorio di Ugento; Claudio Grenzi Editore: Foggia, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).