Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Knowledge of Ancient Monuments: Integrating Archaeological, Archaeometric, and Historical Data to Reconstruct the Building History of the Benedictine Monastery of Catania

Abstract

1. Introduction

- −

- Framing scientific findings within a historical context;

- −

- Increasing or refining knowledge of the building;

- −

- Addressing decisions in restoration interventions by using historically based technical data.

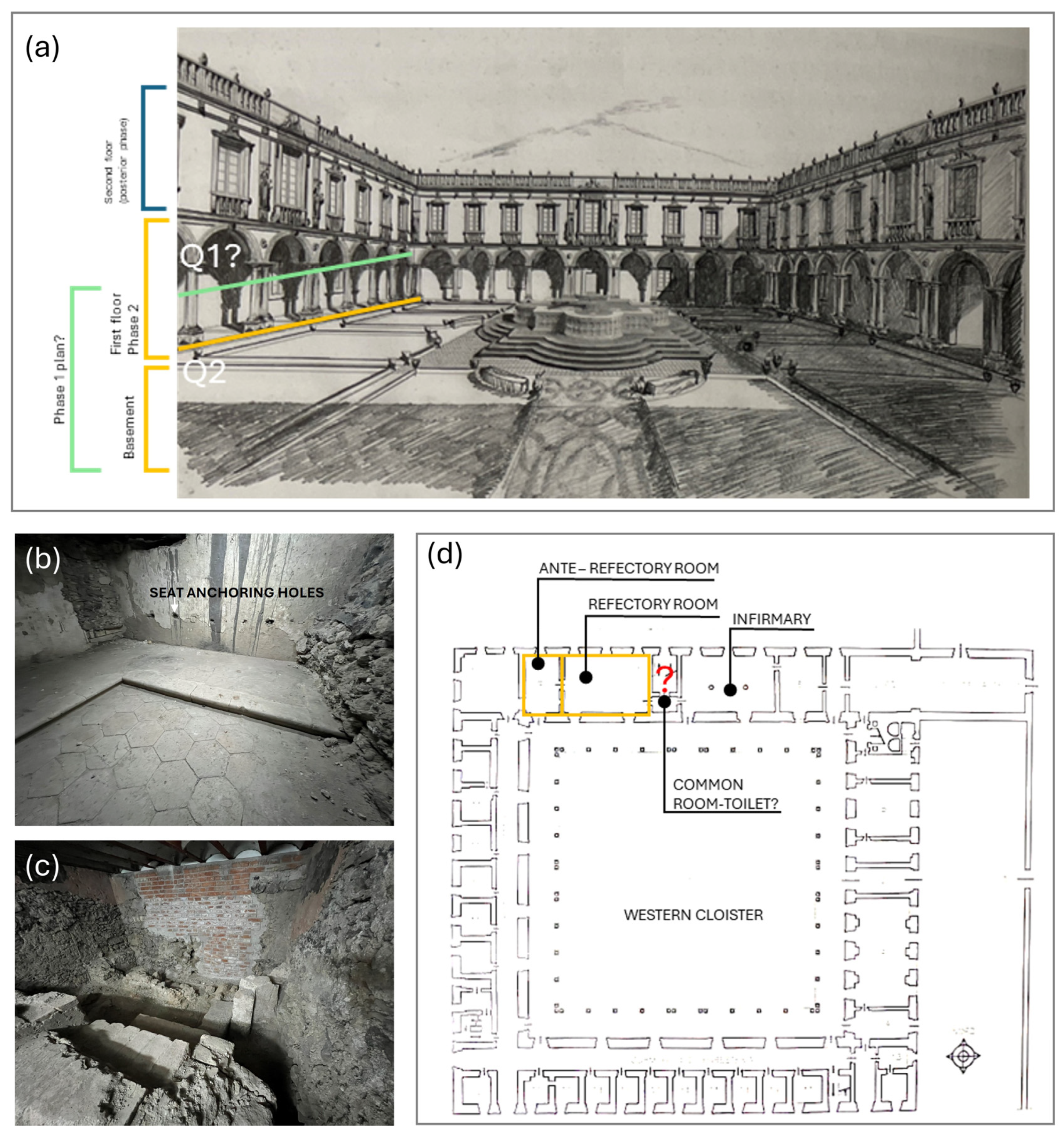

2. Case Study: The Benedictine Monastery in Catania

Studied Areas: “Ancient Refectory Rooms”

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Investigated Materials

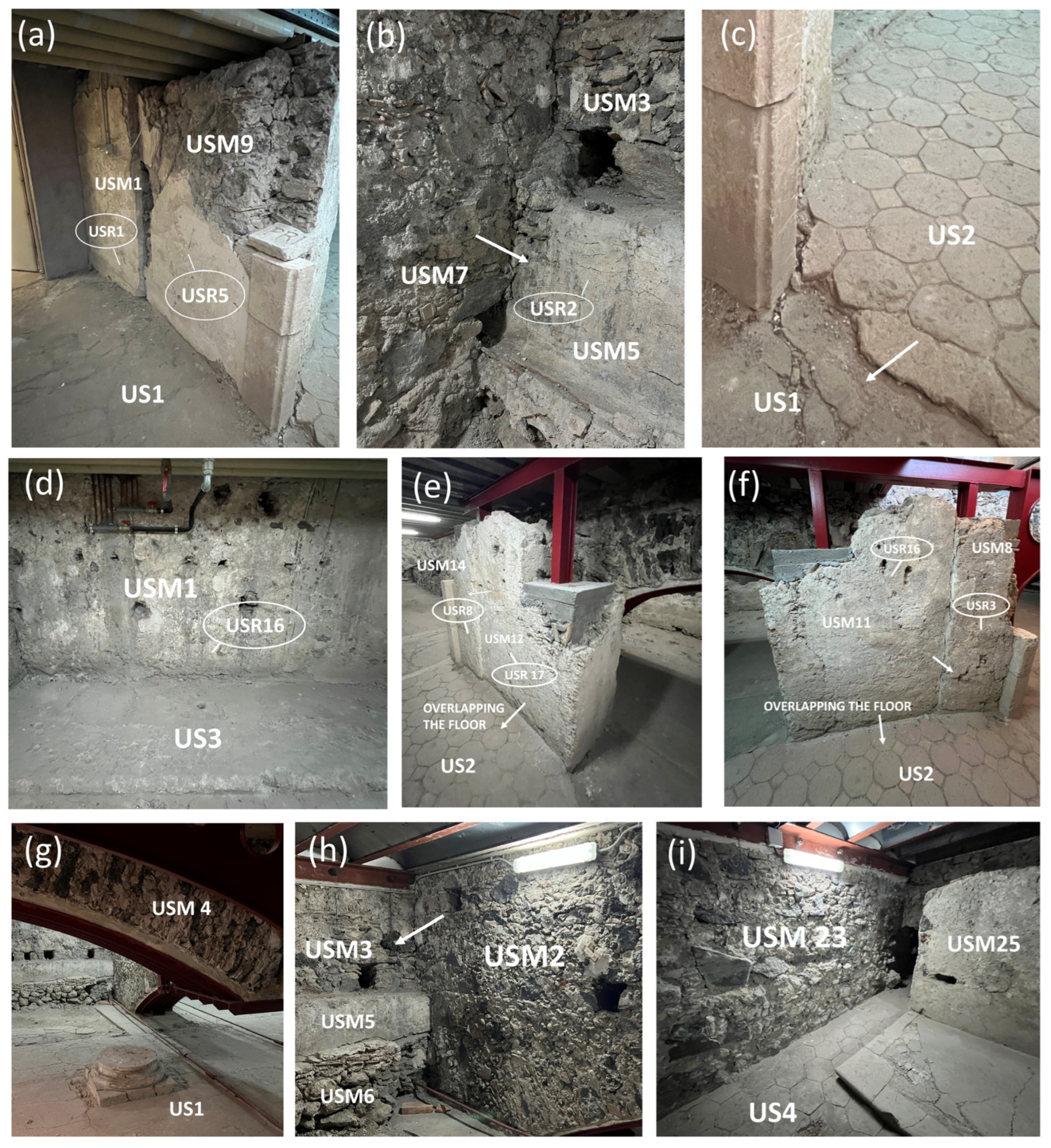

3.2. On-Site Stratigraphic Analysis of Masonries

3.3. On-Site Diagnostic Analyses Through Portable Non-Destructive Instruments

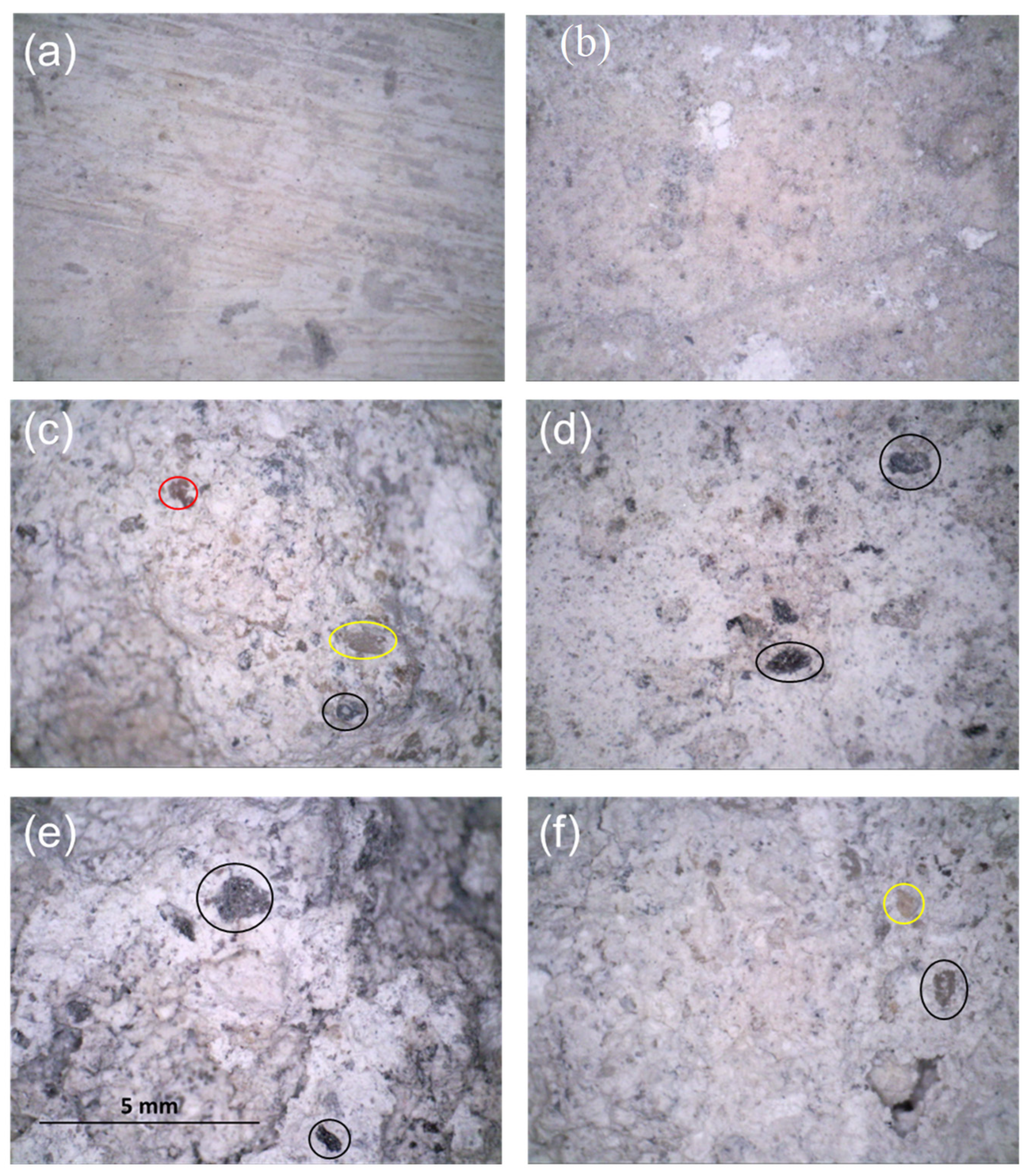

3.3.1. Digital Handheld Microscope

3.3.2. Portable X-ray Fluorescence (pXRF)

3.3.3. Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFT)

4. Results

4.1. Direct Archaeological Studies and Stratigraphic Analysis of Masonries

4.2. Diagnostic In Situ Analyses by Portable Instrumentation

4.2.1. Digital Handheld Microscope

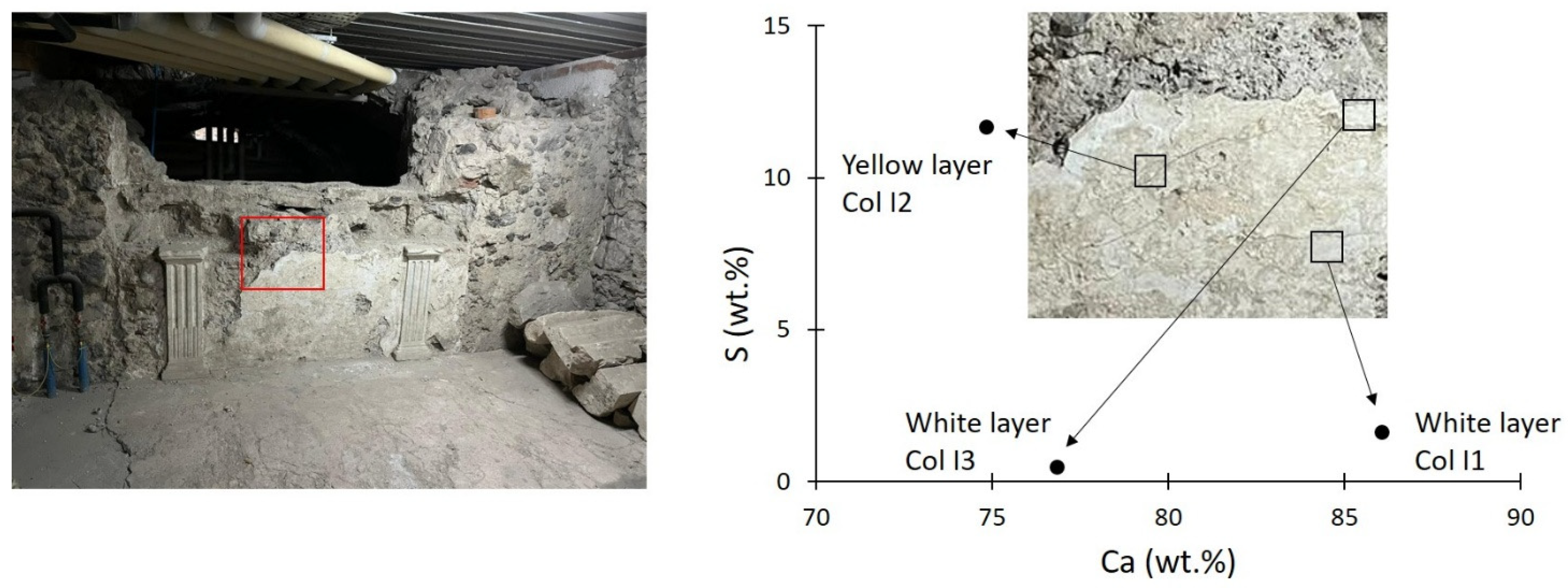

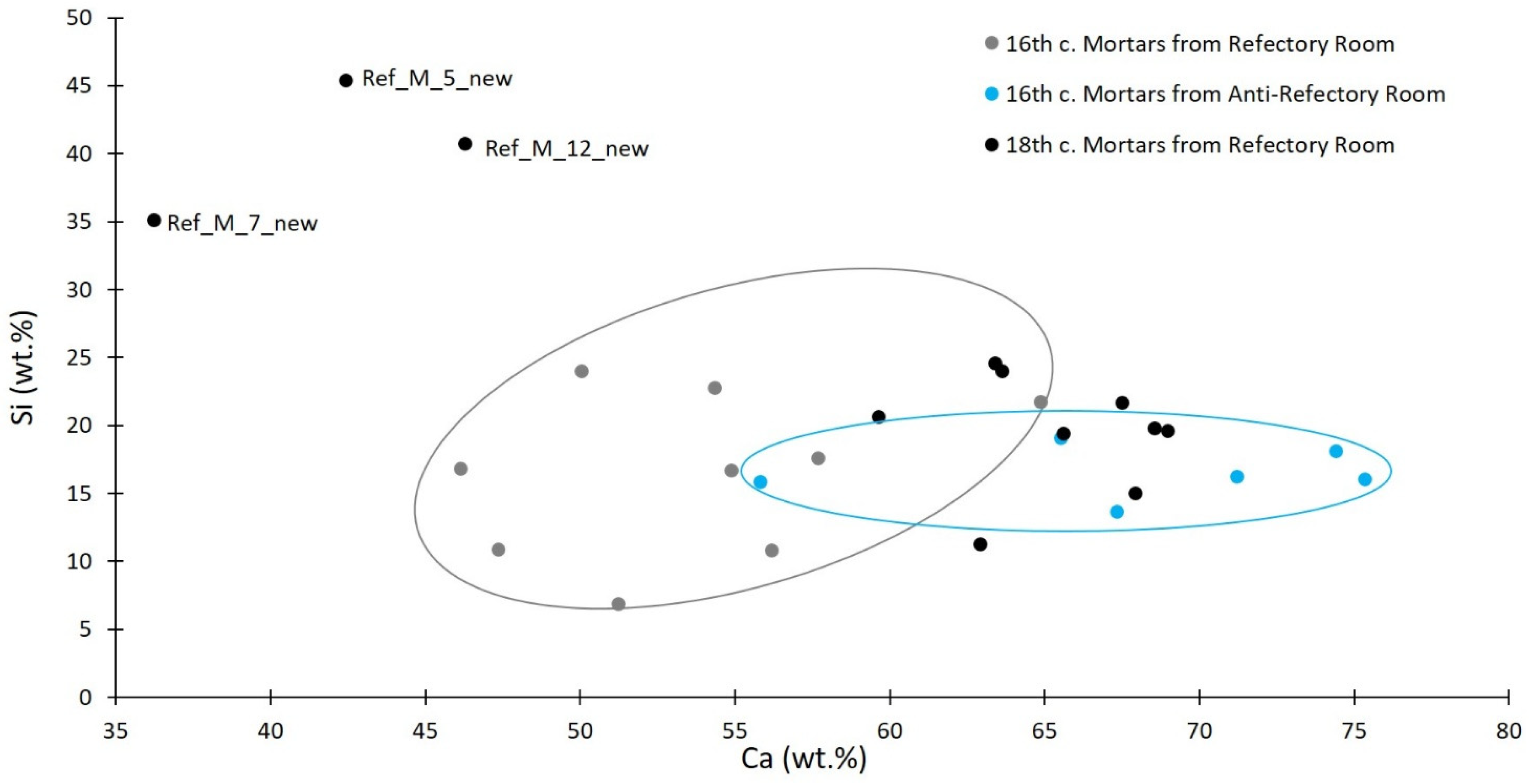

4.2.2. Portable X-ray Fluorescence (pXRF)

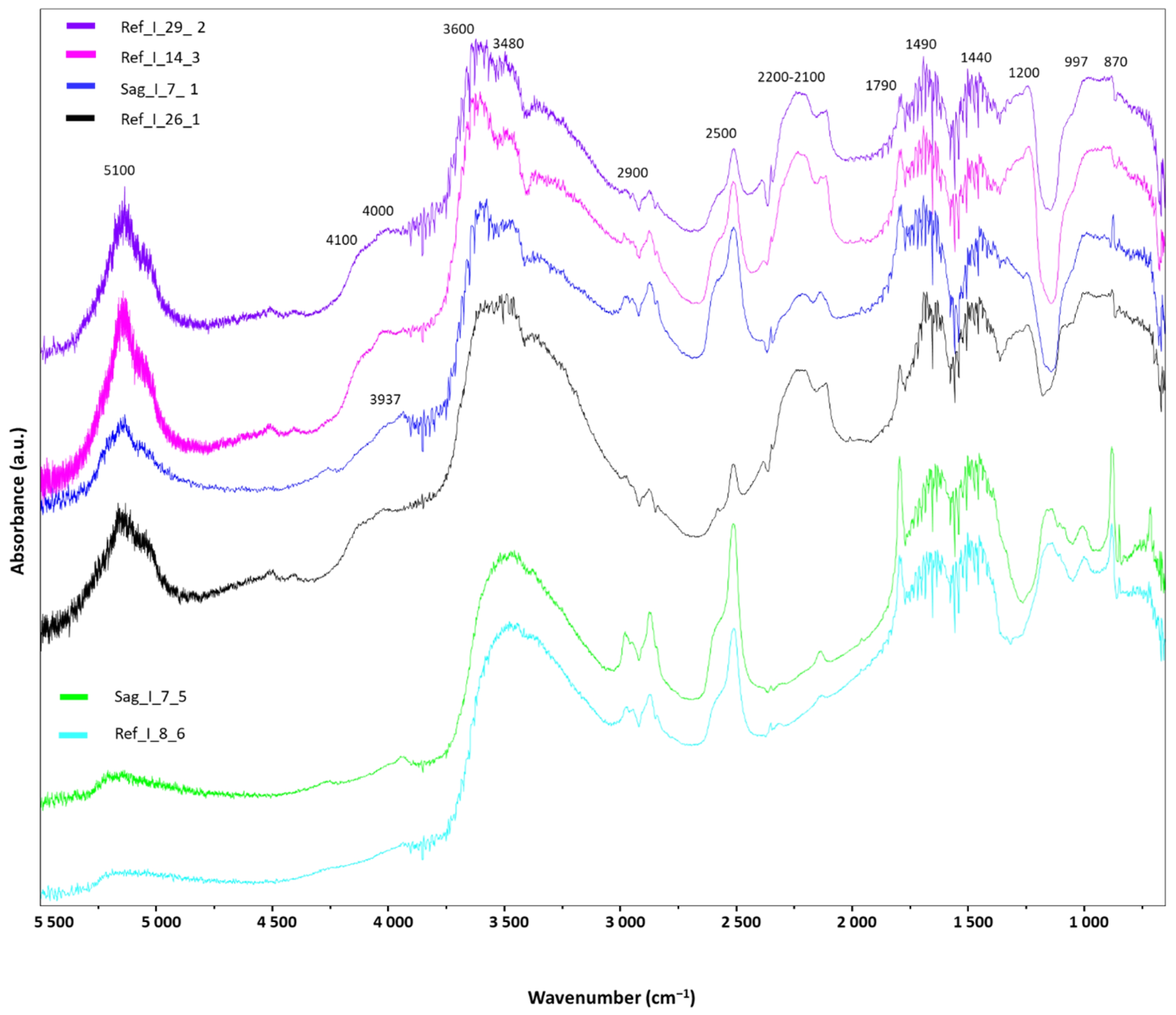

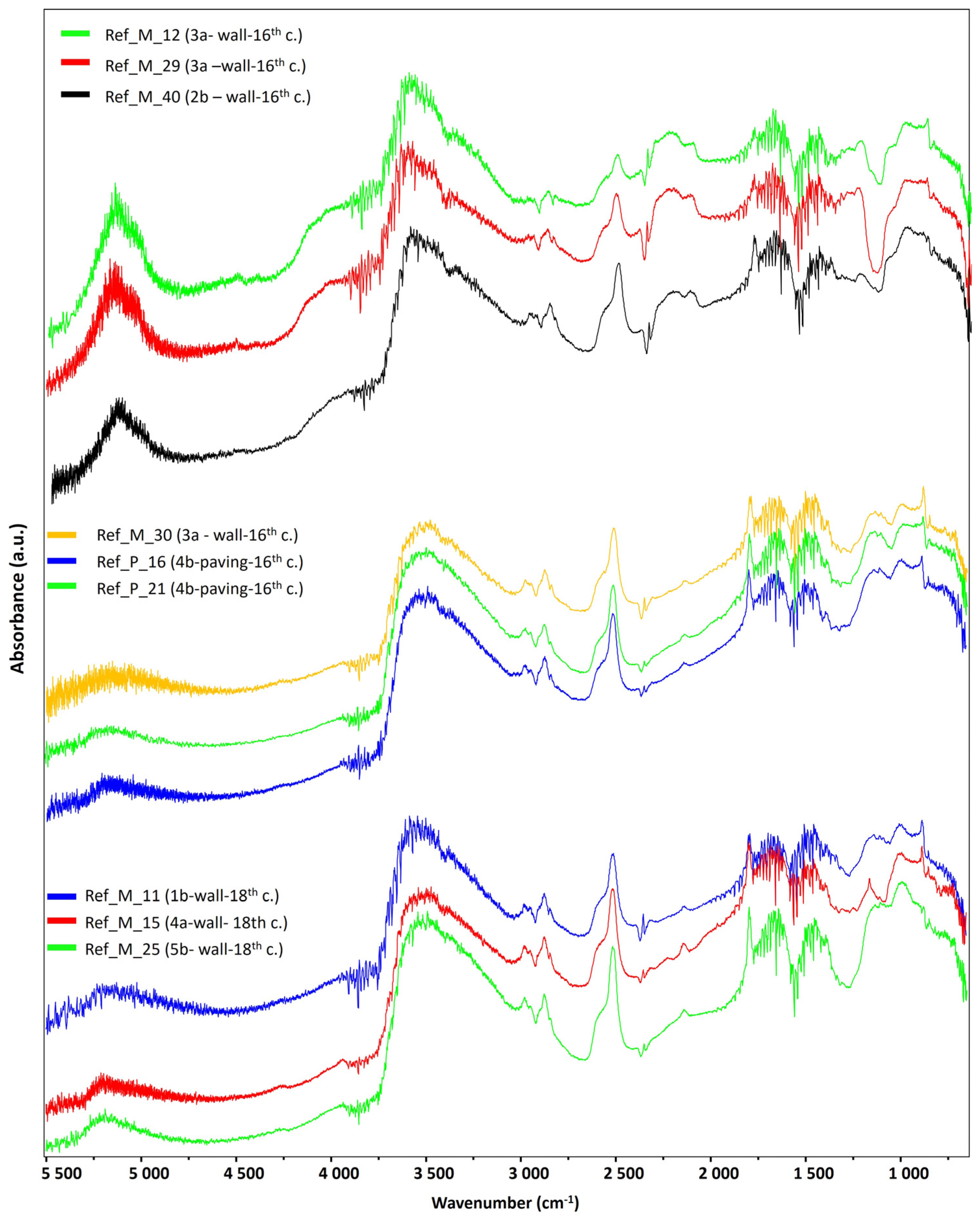

4.2.3. In Situ DRIFT Analyses

5. Discussion

Chronological Framework of Identified Phases

- −

- 1593, when work on the first floor resumed after a seven-year hiatus, but likely in the southern area (dormitories).

- −

- Early 1600s: when new contracts were signed for the completion of the ground floor and it seems that the first floor has been added. By 1613, the first floor would have been completed, including the rooms we are interested in; payments for work in the ante-refectory area are documented in 1610 [28].

- −

- A third potential period is in the range 1617–1630, when the final work on the common areas, such as the ante-refectory, refectory, and infirmary, took place.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tejedor, B.; Lucchi, E.; Bienvenido-Huertas, D.; Nardi, I. Non-destructive techniques (NDT) for the diagnosis of heritage buildings: Traditional procedures and futures perspectives. Energy Build. 2022, 263, 112029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolborea, B.; Baeră, C.; Gruin, A.; Vasile, A.-C.; Barbu, A.-M. A review of non-destructive testing methods for structural health monitoring of earthen constructions. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 114, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosiljkov, V.; Uranjek, M.; Žarnić, R.; Bokan-Bosiljkov, V. An integrated diagnostic approach for the assessment of historic masonry structures. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, E.; Dionísio, A. Main geophysical techniques used for non-destructive evaluation in cultural built heritage: A review. J. Geophys. Eng. 2014, 11, 053001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, G.; Barone, G.; Crupi, V.; Longo, F.; Maisano, G.; Majolino, D.; Mazzoleni, P.; Raneri, S.; Teixeira, J.; Venuti, V. A multi-technique approach for the determination of the porous structure of building stone. Eur. J. Mineral. 2014, 26, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhipinti, R.; Stroscio, A.; Maria Belfiore, C.; Barone, G.; Mazzoleni, P. Chemical and colorimetric analysis for the characterization of degradation forms and surface colour modification of building stone materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 302, 124356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydrych, A.; Jurowski, K. Portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) as a powerful and trending analytical tool for in situ food samples analysis: A comprehensive review of application—State of the art. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 166, 117165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrizabalaga, I.; Gómez-Laserna, O.; Aramendia, J.; Arana, G.; Madariaga, J.M. Applicability of a Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform handheld spectrometer to perform in situ analyses on Cultural Heritage materials. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 129, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrizabalaga, I.; Gómez-Laserna, O.; Carrero, J.A.; Bustamante, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Arana, G.; Madariaga, J.M. Diffuse reflectance FTIR database for the interpretation of the spectra obtained with a handheld device on built heritage materials. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizova, I.; Schultz, J.; Nemec, I.; Cabala, R.; Hynek, R.; Kuckova, S. Comparison of analytical tools appropriate for identification of proteinaceous additives in historical mortars. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Laserna, O.; Cardiano, P.; Diez-Garcia, M.; Prieto-Taboada, N.; Kortazar, L.; Ángeles Olazabal, M.; Madariaga, J.M. Multi-analytical methodology to diagnose the environmental impact suffered by building materials in coastal areas. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 4371–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzi, F.; Stephens, C.H. Advances in Analytical Methods for Cultural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trizio, I.; Savini, F.; Giannangeli, A.; Boccabella, R.; Petrucci, G. The Archaeological Analysis of Masonry for the Restoration Project in Hbim. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W9, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centauro, I.; Vitale, J.G.; Calandra, S.; Salvatici, T.; Natali, C.; Coppola, M.; Intrieri, E.; Garzonio, C.A. A Multidisciplinary Methodology for Technological Knowledge, Characterization and Diagnostics: Sandstone Facades in Florentine Architectural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Rotea, R.; Sanjurjo-Sánchez, J.; Freire-Lista, D.M.; Benavides-García, R. Absolute dating of construction materials and petrological characterisation of mortars from the Santalla de Bóveda Monument (Lugo, Spain). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2024, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fais, S.; Casula, G.; Cuccuru, F.; Ligas, P.; Bianchi, M.G. An innovative methodology for the non-destructive diagnosis of architectural elements of ancient historical buildings. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfitana, D.; Catania, A.M. La Città Antica e Quella del Futuro. Archeologia, Topografia, Urbanistica per la Riqualificazione dello Spazio Urbano; Studia arc.; L’Erma Di Bretschneider: Roma, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pautasso, A. Giovanni Rizza e l’archeologia urbana a Catania nella seconda metà del XX secolo. In Catania Antica. Nuove Prospettive di Ricerca; Dipartimento dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana: Sicily, Italy, 2015; pp. 721–739. [Google Scholar]

- Mattaliano, F. Thuc. VI 3, 2: I Corinzi, Ortigia e Siracusa polyanthropos. In Dal Mito Alla Storia: La Sicilia nell’Archaiologhia di Tucidide: Atti del VIII Convegno di Studi; Sciascia: Sicily, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frasca, M. Gli scavi all’interno dell’ex monastero dei Benedettini e lo sviluppo urbano di Catania antica. In Catania Antica, Nuove Prospettive di Ricerca; Dipartimento dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana: Sicily, Italy, 2015; pp. 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti, F. L’acropoli di Catania nella preistoria. In Catania Antica. Nuove Prospettive di Ricerca; Dipartimento dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana: Sicily, Italy, 2015; pp. 33–98. [Google Scholar]

- Branciforti, M.G. Da Katane a Catina. In Tra Lava e Mare. Contributi All’archaiologhia di Cataniua; Private and Various Editions: Catania, Italy, 2010; pp. 135–258. [Google Scholar]

- Tortorici, E. Catania antica: La carta archeologica. In Catania Antica; Archeologica, S., Ed.; L’ERMA di Bretschneider: Roma, Italy, 2016; pp. 1–472. [Google Scholar]

- Caliò, L.M.; Camera, M. Le pitture parietali degli scavi al Monastero dei Benedettini. In Proceedings of the Atti Delle Giornate Gregoriane XIII Edizione, Agrigento, Italy, 29 November–1 December 2019; Ante Quem: Bologna, Italy, 2020; pp. 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Branciforti, M.G. Mosaici di età imperiale romana a Catania. In Atti del IV Colloquio dell’Associazione Italiana per lo Studio e la Conservazione del Mosaico, Palermo, 9–13 dicembre 1996; Carra Bonacasa, R.M., Guidobaldi, F., Eds.; Edizioni del Girasole: Ravenna, Italy, 1997; pp. 165–186. [Google Scholar]

- Arcifa, L. Da Agata al Liotru: La costruzione dell’identità urbana nell’alto medieovo. In Tra Lava e Mare. Contributi All’archaiologhia di Catania; Private and Various Editions: Catania, Italy, 2010; pp. 355–386. [Google Scholar]

- Militello, P. Un monumento di gloria della nostra Catania» Il monastero benedettino di San Nicolò l’Arena tra XVI e XIX secolo. In Breve Storia del Monastero dei Benedettini di Catania; Giuseppe Maimone Editore: Taormina, Italy, 2014; pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Calogero, S.M. Il Monastero Catanese di San Nicolò l’Arena. Dalla Posa della Prima Pietra alla Confisca Post-Unitaria; Editoriale Agorà: Milan, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boato, A. L’archeologia in Architettura. Misurazioni, Stratigrafie, Datazioni, Restauro; Marsilio: Venice, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brogiolo, G.P.; Cagnana, A. Archeologia Dell’architettura. Metodi e Interpretazioni; All’Insegna del Giglio: Sesto Fiorentino, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Doglioni, F. Stratigrafia e restauro. In Tra Conoscenza e Conservazione Dell’architettura; Lint Editoriale: Trieste, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Beltramo, S. Stratigrafia Dell’architettura e Ricerca Storica, 2009th ed.; Bussole, Ed.; Carrocci Editore: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arizzi, A.; Cultrone, G. Mortars and plasters—How to characterise hydraulic mortars. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2021, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.L. Combination Bands in the Infrared Spectroscopy of Kaolins—A Drift Spectroscopic Study. Clays Clay Miner. 1998, 46, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, V.C. (Ed.) The Infrared Spectra of Minerals; Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland: Middlesex, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, M.; Smith, D.C. Catalogue of 45 reference Raman spectra of minerals concerning research in art history or archaeology, especially on corroded metals and coloured glass. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2003, 59, 2247–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzi Pezzolo, A.; Colombi, M.; Mazzocchin, G.A. Spectroscopic and Chemometric Comparison of Local River Sands with the Aggregate Component in Mortars from Ancient Roman Buildings Located in the X Regio Between the Livenza and Tagliamento Rivers, Northeast Italy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2018, 72, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madejová, J. FTIR techniques in clay mineral studies. Vib. Spectrosc. 2003, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, P.; Colomban, P.; Tournié, A.; Macchiarola, M.; Ayed, N. A non-invasive study of Roman Age mosaic glass tesserae by means of Raman spectroscopy. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 2551–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarrizzo, G. Catania e il Suo Monastero: S. Nicolò l’Arena, 1846; Giuseppe Maimone Editore: Catania, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zito, G. Documenti sui benedettini siciliani dal monastero di S. Nicola l’arena all’archivio storico diocesano di Catania. In Stud Mem di don Faustino Avagliano; Sodalitas, Ed.; Pubblicazioni Cassineri: Cassino, Italy, 2016; pp. 1251–1266. [Google Scholar]

| Elemental Composition (wt.%) | Al | Ca | Fe | K | Mn | S | Si | Ti | Ca/S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasters | |||||||||

| Refectory Room—16th c. | |||||||||

| Ref 1b I1 | 3.66 | 83.59 | 1.43 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 4.34 | 6.07 | 0.30 | 19 |

| Ref 1b I2 | 6.48 | 70.95 | 1.57 | 0.89 | 0.06 | 4.75 | 14.96 | 0.34 | 15 |

| Ref 1b I3 | 5.88 | 76.68 | 0.87 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 8.68 | 7.27 | 0.19 | 9 |

| Ref 1a I1 | 3.31 | 50.73 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 42.43 | 3.03 | 0.06 | 1 |

| Ref 1a I3 | 5.55 | 45.44 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 47.05 | 1.56 | 0.08 | 1 |

| Ref 1a I2 | 5.58 | 45.52 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 43.37 | 4.90 | 0.12 | 1 |

| Ref 1a I4 | 7.75 | 70.52 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 17.43 | 3.98 | 0.08 | 4 |

| Ref 1a I5 | 4.15 | 45.62 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 46.45 | 3.48 | 0.05 | 1 |

| Ref 1a I6 | 2.22 | 50.68 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 42.81 | 3.68 | 0.10 | 1 |

| Ref 1a I7 | 8.70 | 44.87 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 40.73 | 5.08 | 0.11 | 1 |

| Ref 1a I8 | 9.48 | 75.42 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 11.69 | 2.93 | 0.14 | 6 |

| Ref 1a I9 | 10.05 | 76.28 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 8.70 | 4.28 | 0.14 | 9 |

| Ref 3a I1 | 8.63 | 81.43 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 2.20 | 7.08 | 0.14 | 37 |

| Ref 3a I2 | 2.45 | 66.23 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 26.84 | 4.03 | 0.14 | 2 |

| Ref 3a I3 | 6.21 | 70.24 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 13.19 | 9.87 | 0.12 | 5 |

| Ref 3a I4 | 6.91 | 85.12 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 1.42 | 5.61 | 0.19 | 60 |

| Ante-Refectory Room | |||||||||

| Col I1 | 5.74 | 86.05 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 1.62 | 6.09 | 0.15 | 53 |

| Col I2 | 3.48 | 74.85 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 11.67 | 8.73 | 0.24 | 6 |

| Col I3 | 18.38 | 76.84 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 3.98 | 0.09 | 162 |

| Mortars | |||||||||

| Refectory Room—16th c. | |||||||||

| Ref 1a M1 | 9.27 | 46.14 | 2.39 | 1.20 | 0.07 | 23.59 | 16.82 | 0.50 | 2 |

| Ref 1a M2 | 6.27 | 64.87 | 2.79 | 1.40 | 0.12 | 2.31 | 21.71 | 0.53 | 28 |

| Ref 3a M1 | 13.26 | 54.90 | 2.04 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 11.68 | 16.67 | 0.41 | 5 |

| Ref 3a M2 | 9.40 | 50.05 | 1.49 | 1.02 | 0.04 | 13.66 | 24.00 | 0.34 | 4 |

| Ref 3a M3 | 16.01 | 57.69 | 1.57 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 5.94 | 17.58 | 0.38 | 10 |

| Ref 3a M4 | 5.48 | 54.34 | 1.89 | 1.30 | 0.04 | 13.82 | 22.77 | 0.36 | 4 |

| Ref 2b M1 | 6.11 | 56.18 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.04 | 24.83 | 10.81 | 0.31 | 2 |

| Ref 2b M2 | 11.91 | 47.38 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 28.16 | 10.88 | 0.20 | 2 |

| Ref 2b M3 | 12.74 | 51.24 | 0.82 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 27.62 | 6.88 | 0.43 | 2 |

| Ante-Refectory Room—16th c. | |||||||||

| Col M1 | 4.54 | 74.43 | 1.07 | 1.51 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 18.09 | 0.30 | >100 |

| Col M2 | 10.40 | 71.22 | 0.87 | 0.39 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 16.20 | 0.24 | >100 |

| Col M3 | 4.68 | 75.34 | 0.85 | 0.44 | 0.06 | 2.33 | 16.01 | 0.29 | 32 |

| Col M4 | 14.29 | 55.81 | 2.21 | 1.04 | 0.06 | 10.38 | 15.84 | 0.37 | 5 |

| Col M5 | 5.38 | 65.53 | 2.11 | 1.03 | 0.06 | 6.17 | 19.10 | 0.62 | 11 |

| Col M6 | 14.16 | 67.35 | 1.69 | 0.64 | 0.11 | 2.10 | 13.66 | 0.30 | 32 |

| Refectory Room—18th c. | |||||||||

| Ref_M_2_new | 9.32 | 63.63 | 1.28 | 1.30 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 23.96 | 0.32 | >100 |

| Ref_M_3_new | 5.11 | 67.52 | 2.76 | 2.08 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 21.65 | 0.65 | >100 |

| Ref_M_4_new | 7.25 | 63.40 | 1.98 | 1.92 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 24.58 | 0.45 | >100 |

| Ref_M_5_new | 7.86 | 42.45 | 1.22 | 1.62 | 0.02 | 1.17 | 45.36 | 0.30 | 36 |

| Ref_M_7_new | 8.68 | 36.24 | 3.37 | 2.62 | 0.08 | 13.22 | 35.07 | 0.72 | 3 |

| Ref_M_9_new | 5.01 | 62.93 | 1.45 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 17.97 | 11.25 | 0.38 | 4 |

| Ref_M_10_new | 12.27 | 59.64 | 2.24 | 1.39 | 0.06 | 3.28 | 20.60 | 0.52 | 18 |

| Ref_M_12_new | 6.36 | 46.30 | 3.02 | 1.91 | 0.06 | 0.89 | 40.70 | 0.77 | >100 |

| Ref_M_13_new | 13.32 | 67.94 | 1.74 | 1.11 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 14.98 | 0.39 | >100 |

| Ref_M_14_new | 6.13 | 68.97 | 2.85 | 1.59 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 19.57 | 0.66 | >100 |

| Ref_M_15_new | 10.31 | 65.62 | 2.26 | 1.54 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 19.36 | 0.55 | >100 |

| Ref_M_17_new | 5.21 | 68.55 | 3.35 | 1.59 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 19.80 | 0.80 | >100 |

| Data Integration Table | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Phase 2A | Phase 2B | Phase 2C | Phase 3 | Phase 4 | |

| Chronology | 1558–1562 | 1569–1583 | Range 1593–1630 | Range 1593–1630 | Post 1669, about 1673 | Post1693 (XVIII century) |

| USM | 1–3–5 | 26–25–6 | 7–8–9–17–13−14 | 12–11 | 28 | 2–4–15–16–19–22–20–23–24 |

| TM | 2 | 3 | 4 | / | / | 1 |

| US | 1–4 | 2–3 | / | / | / | |

| USR | 1–2–6–7–12–13–14–15 | 10–5–9–8–3 | 17–16–11 | / | / | |

| Samples | Ref_M_23 | Ref_M_26 Ref_M_27 Ref_M_28 Ref_M_12 Ref_M_40 Ref_M_23 | Ref_M_29 Ref_M_30 Ref_M_-11 | No sample | No sample | Ref_M_11 Ref_M_15 Ref_M_25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Occhipinti, R.; Fugazzotto, M.; Belfiore, C.M.; Longhitano, L.; Gerogiannis, G.M.; Mazzoleni, P.; Militello, P.M.; Barone, G. Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Knowledge of Ancient Monuments: Integrating Archaeological, Archaeometric, and Historical Data to Reconstruct the Building History of the Benedictine Monastery of Catania. Heritage 2025, 8, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110467

Occhipinti R, Fugazzotto M, Belfiore CM, Longhitano L, Gerogiannis GM, Mazzoleni P, Militello PM, Barone G. Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Knowledge of Ancient Monuments: Integrating Archaeological, Archaeometric, and Historical Data to Reconstruct the Building History of the Benedictine Monastery of Catania. Heritage. 2025; 8(11):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110467

Chicago/Turabian StyleOcchipinti, Roberta, Maura Fugazzotto, Cristina Maria Belfiore, Lucrezia Longhitano, Gian Michele Gerogiannis, Paolo Mazzoleni, Pietro Maria Militello, and Germana Barone. 2025. "Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Knowledge of Ancient Monuments: Integrating Archaeological, Archaeometric, and Historical Data to Reconstruct the Building History of the Benedictine Monastery of Catania" Heritage 8, no. 11: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110467

APA StyleOcchipinti, R., Fugazzotto, M., Belfiore, C. M., Longhitano, L., Gerogiannis, G. M., Mazzoleni, P., Militello, P. M., & Barone, G. (2025). Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Knowledge of Ancient Monuments: Integrating Archaeological, Archaeometric, and Historical Data to Reconstruct the Building History of the Benedictine Monastery of Catania. Heritage, 8(11), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110467