Agritourism in Extremadura, Spain from the Perspective of Rural Accommodations: Characteristics and Potential Development from Agrarian Landscapes and Associated Activities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- O1: To know the main aspects that define the owners of the rural tourism offer implanted in Extremadura, Spain.

- -

- O2: To know the conceptualization of agritourism that the owners of rural lodgings have.

- -

- O3: To know the opportunities that rural lodging can offer to develop an agritourism product.

- -

- O4: To know the services and activities offered.

- -

- O5: To know if the potential or intentionality corresponds to reality.

- -

- O6: To discover distribution patterns in the activities offered by rural lodgings.

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Profile of the Rural Lodging Owner

4.2. Conceptualization

4.3. Housing

4.3.1. Potential for Activity Development

4.3.2. Intention to Engage in Agritourism

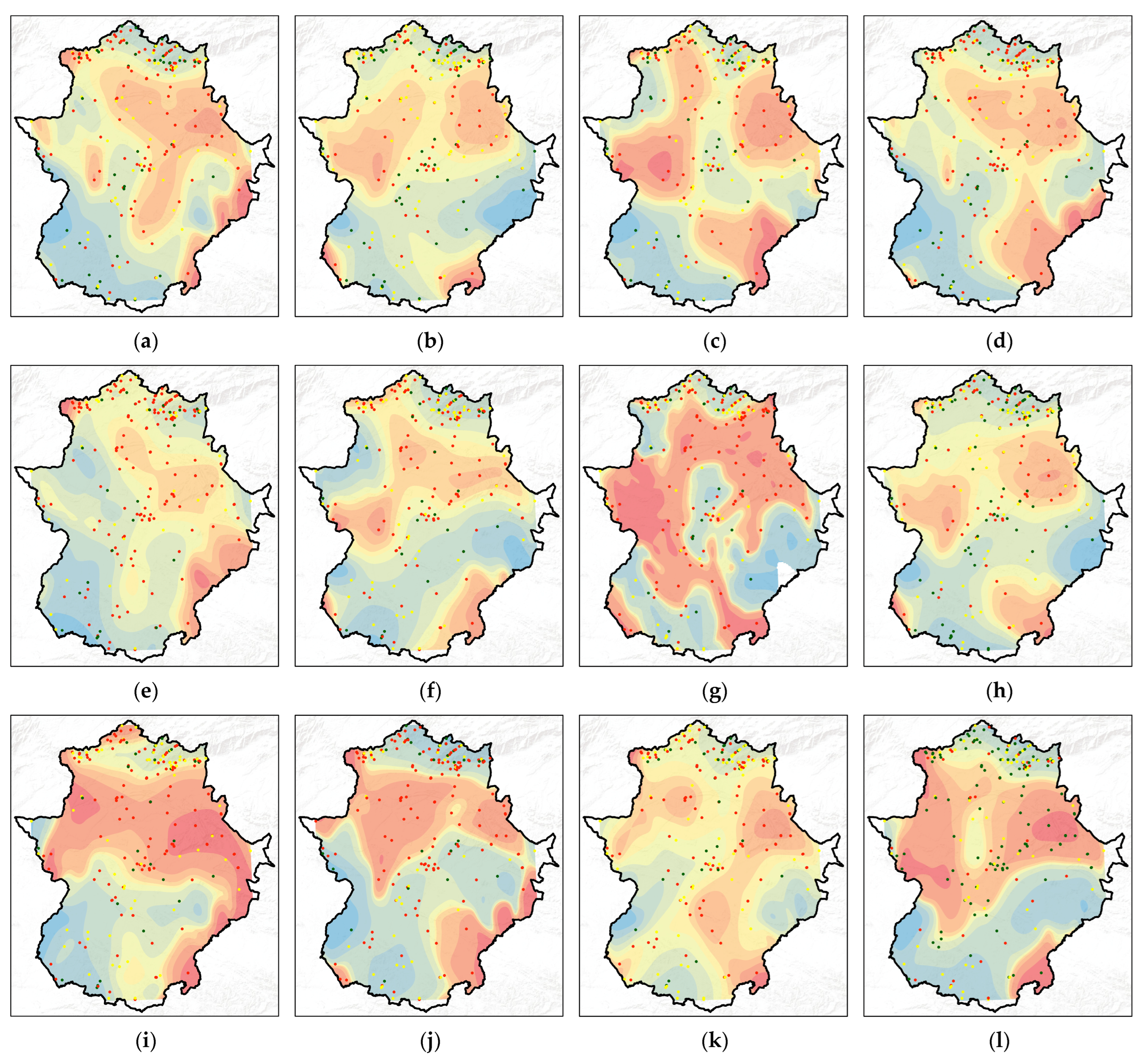

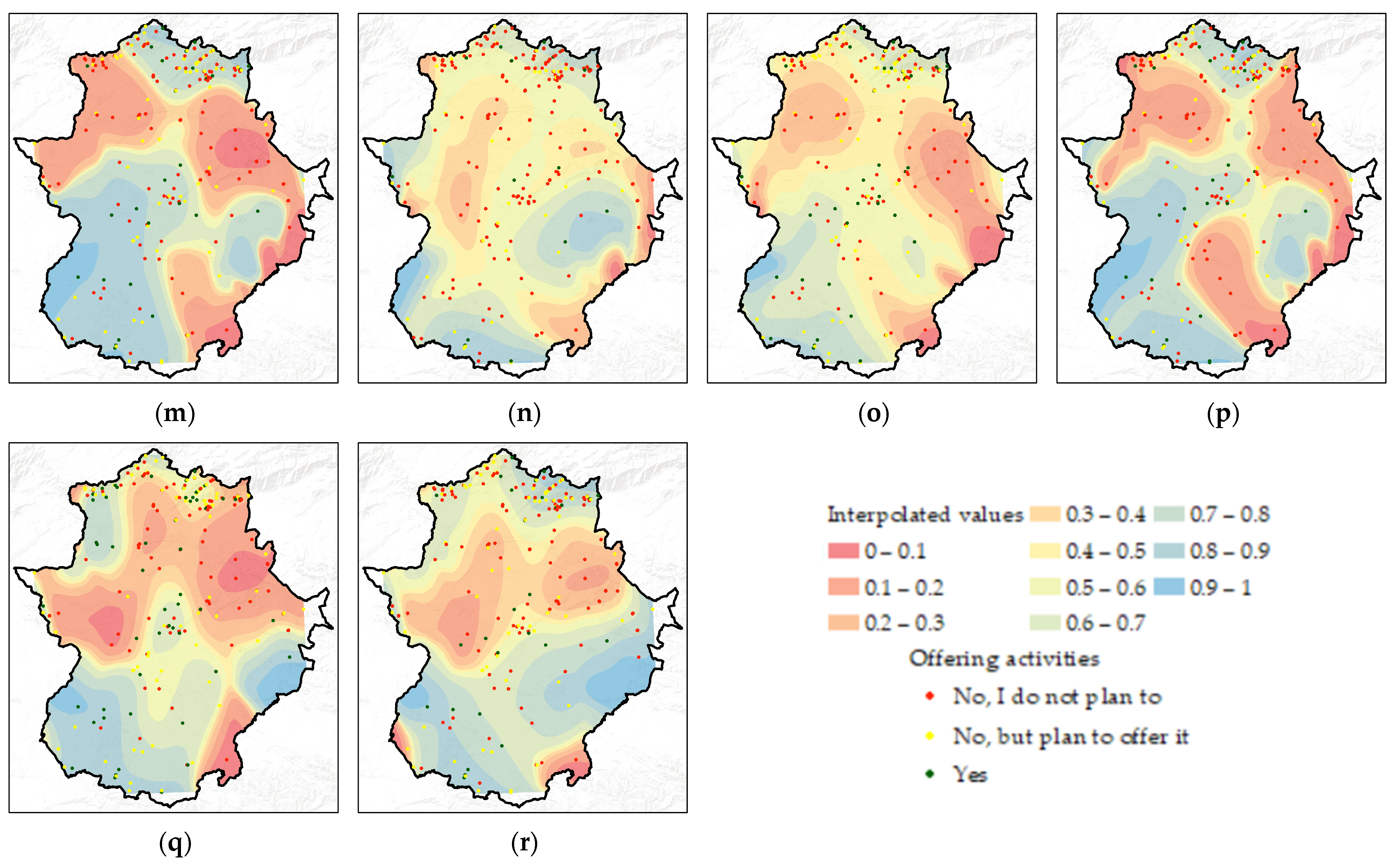

4.4. Territorial Analysis: Searching for Spatial Patterns

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questions | Responses |

|---|---|

| Owner’s age group | Up to 30 years old/31 to 40 years old/41 to 50 years old/Over 50 years old |

| Seniority in the sector | Less than 5 years/From 5 to 10 years/More than 10 years |

| Level of education | Primary/Middle/University |

| Language skills | English/French/Portuguese/Italian/German (1 = None; 5 = very good) |

| Complementary economic activities | Lodging is the only source of income/Income from agriculture or animal husbandry/Income from handicrafts/Income from industry/Income from liberal professions/Income from the service sector/Income from several sectors |

| Reasons for going into business | Self-employment/Obtaining supplementary income/Family tradition/Vocation for tourism/Other reason |

| Type of accommodation | Rural house, rural hotel, rural apartment, rural cottage, hut |

| Do you consider that your accommodation falls into the agritourism category? | Yes/No/Not sure |

| What does agritourism mean to you? | Overnight stay in rural lodgings/Overnight stay in an agricultural or livestock farm and participate in agricultural work/Practice tourism to learn about the rural way of life/Carry out activities in an agricultural or livestock farm, even if you spend the night in another place/Practice tourism in direct contact with nature/ Overnight stay on an agricultural or livestock farm |

| According to you, which activity would best define agritourism? | Rural lodging/Lodging on agricultural and livestock farms exclusively/Education and awareness of the values of the rural environment/Attendance at gastronomic festivals, visits to markets of traditional food products, etc./Participation in agricultural tasks/I don’t know/Enjoyment of the freedom and tranquility offered by the rural world/Combination of several answers/With my size and low rent, the demand for agricultural tasks from tenants is low/Education and awareness of the values of the rural environment by participating in agricultural tasks/Lodging in farms that offer rural and agricultural activities |

| Do you have an agricultural or livestock farm to complement your accommodation? | No, and I am not considering it either/I do not have a farm, although I could reach an agreement with farmers and ranchers in the area to complement my offer with theirs/Yes, dedicated to agriculture/I have a small orchard and farm to offer it as a complementary product/Yes, for recreation/Yes, dedicated to extensive livestock farming |

| What type of agricultural landscape or livestock use predominates in the vicinity of your accommodation? | Rivers or tributaries/Wooded dehesas with oak trees/Reservoirs/Olive groves/Vineyards/Stone fruit trees/Organic crops/Irrigated crops/Rainfed crops/Cattle/Goats/Sheep/Sheep |

| What services does your accommodation provide? | Bicycle rental/Advice about the area/Bar/cafeteria/ Barbecue/Cold rooms for game storage/Swimming pool/Restaurant/Free WI-FI/Sale of handicraft products/Sale of local gastronomic products/Sale of home-made products (sweets, cheeses, sausages, etc.) |

| Organize one of the following activities in the nearby dehesas | Tasting of local products/Monasteries/Sky watching/Bird watching/Wildlife watching/Participation in agricultural tasks/Collection of wild products/Walking tours to collect products (asparagus, mushrooms…)/Tours in 4 × 4 or similar/Bicycle tours/Horseback riding/Photographic safaris/Visit to ancestral constructions/Visit to bullfighting cattle ranches/Visit to producers/Visit to producers/Visit to producers…)/Tours in 4 × 4 or similar/Bicycle tours/Horseback riding/Photographic safaris/Visit to ancestral constructions/Visit to bullfighting ranches/Visit to producers/Visit to artisans or ancestral crafts/Visit to wineries/Visit to olive oil mills. |

References

- Tirado Ballesteros, J.G.; Hernández, M.H. Promoting tourism through the EU LEADER programme: Understanding Local Action Group governance. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto-Martos, J.C.; Voth, A.; Pinos-Navarrete, A. The importance of tourism in rural development in Spain and Germany. In Neoendogenous Development in European Rural Areas: Results and Lessons; Cejudo, E., Navarro, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, N.; Liargovas, P.; Stavroyiannis, S.; Makris, I.; Apostolopoulos, S.; Petropoulos, D.; Anastasopoulou, E. Sustaining rural areas, rural tourism enterprises and EU development policies: A multi-layer conceptualisation of the obstacles in Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.A.P.; Miriam-Hermi, Z.; García Marín, R. Políticas gubernamentales y difusión del turismo de interior en el marco del paradigma de la sostenibilidad: Brasil y España. Investig. Tour. 2023, 26, 56–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cànoves, G.; Villarino, M.; Herrera, L. Políticas públicas, turismo rural y sostenibilidad: Difícil equilibrio. Bull. Assoc. Span. Geogr. 1997, 41, 199–217. Available online: https://bage.age-geografia.es/ojs/index.php/bage/article/view/1997 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Sánchez-Martín, J.M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I.; Blas-Morato, R. Implantación de alojamientos en el medio rural y freno a la despoblación: Realidad o ficción. El caso de Extremadura (España). Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2020, 76, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarios Trigueros, M.; Morales Prieto, E. Sostenibilidad y políticas de desarrollo rural: El caso de la Tierra de Campos vallisoletana. Cuad. Geogr. 2020, 59, 224–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián Abellán, A. Gestión ambiental y turismo sostenible. In Desarrollo en las Iniciativas Comunitarias de Sierra del Segura (Albacete); Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.A.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Vargas-Vargas, M. Análisis del turismo cultural en Castilla-La Mancha (ESPAÑA). El impacto de los programas europeos de desarrollo rural LEADER y PRODER. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2008, 17, 364–378. [Google Scholar]

- Soler Vayá, F.; San-Martín González, E. Impacto de la metodología Leader en el turismo rural. Una propuesta de análisis cuantitativo. Investig. Tour. 2023, 25, 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Figueras, C.; Cantarero Prados, F.J.; Enrique Sayago, P. 30 años de LEADER en Andalucía. Diversificación, turismo rural y crecimiento inteligente. Investig. Geogr. 2022, 78, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento González, R.M.; Lazovski, O. The impact of depopulation on the development of tourism in a rural area: The case of Ribeira Sacra. J. Tour. Herit. Res. 2022, 5, 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Soler Vayá, F.; San Martín González, E. Efectos del turismo rural sobre la evolución demográfica en municipios rurales de España. Ager Rev. Estud. Sobre Despoblación Desarro. Rural 2022, 35, 131–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengifo-Gallego, J.I.; Martín-Delgado, L.M.; Sánchez-Martín, J.M. Agroturism and dehesas: A Strategy to fix population in rural areas of Extremadura (Spain). Lurralde Investig. Espac. 2023, 46, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.M.; Blas-Morato, R.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I. The dehesas of Extremadura, Spain: A potential for socio-economic development based on agritourism activities. Forests 2019, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.M.; Gurría-Gascón, J.L.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I. The distribution of rural accommodation in Extremadura, Spain—Between the randomness and the suitability achieved by means of regression models (OLS vs. GWR). Sustainability 2020, 12, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.M.; Hernández-Carretero, A.M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I.; García-Berzosa, M.J.; Martín-Delgado, L.M. Modeling the Potential for Rural Tourism Development via GWR and MGWR in the Context of the Analysis of the Rural Lodging Supply in Extremadura, Spain. Systems 2023, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiarowski, W. Some problems in the evaluation of the natural environment for the demands of tourism and recreation: A case study of the Bydgoszcz Region. Geogr. Pol. 1977, 34, 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Warszynska, J. An evaluation of the resources of the natural environment for tourism and recreation. Geogr. Pol. 1977, 34, 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Mieczkowski, Z. The tourism climatic index: A methos of evaluating world climates for tourism. Can. Geogr. 1985, 29, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.-M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.-I.; Martín-Delgado, L.-M.; Hernández Carretero, A.-M. Methodological System to Determine the Development Potential of Rural Tourism in Extremadura, Spain. Systems 2022, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leno Cerro, F. Técnicas de Evaluación del Potencial Turístico; Centro de Publicaciones: Madrid, Spain; Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología: Madrid, Spain, 1993; p. 300.

- Zimmer, P.; Grassmann, S. Evaluar el Potencial Turístico de un Territorio. Observatorio Europeo Leader. 1997, p. 43. Available online: https://resource-centre.aeidl.eu/GED_CYY/194843591202/LEADER_tourisme-ES.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Sánchez Martín, J.M.; Sánchez Rivero, M.; Rengifo Gallego, J.I. La evaluación del potencial para el desarrollo del turismo rural. Aplicación metodológica sobre la provincia de Cáceres. GeoFocus Int. Rev. Geogr. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2013, 13, 99–130. [Google Scholar]

- López-Sanz, J.M.; Penelas-Leguía, A.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. Rural Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals. A Study of the Variables That Most Influence the Behavior of the Tourist. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 722973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I. Evolución del sector turístico en la Extremadura del Siglo XXI: Auge, crisis y recuperación. Lurralde Investig. Espac. 2019, 42, 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sanz, J.M.; Penelas-Leguía, A.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. Sustainable Development and Consumer Behavior in Rural Tourism—The Importance of Image and Loyalty for Host Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sanz, J.M.; Penelas-Leguía, A.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. Sustainable Development and Rural Tourism in Depopulated Areas. Land 2021, 10, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J.; Wall, G. Linkages Between Tourism and Food Production. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.; Momsen, J. Challenges and potential for linking tourism and agriculture to achieve pro-poor tourism objectives. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2004, 4, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R. Linkages between tourism and agriculture in Mexico. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 546–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choenkwan, S.; Promkhambut, A.; Hayao, F.; Rambo, A.T. Does Agrotourism Benefit Mountain Farmers? A Case Study in Phu Ruea District, Northeast Thailand. Mt. Res. Dev. 2016, 36, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Xu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, Z.; Li, L.; Yturralde, C.C.; Valencia, L.G. Research on the integrated development of agriculture and tourism in inner Mongolia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 14877–14892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, N.-W.; Chen, Y.-J.; Huang, C.-L. Linkages between organic agriculture and agro-ecotourism. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2008, 21, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Zhou, Z.; Kim, D.J. A New Path of Sustainable Development in Traditional Agricultural Areas from the Perspective of Open Innovation—A Coupling and Coordination Study on the Agricultural Industry and the Tourism Industry. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirato, S.; Felicetti, A.M.; Raso, C.; Pansera, B.A.; Violi, A. Agritourism and Sustainability: What We Can Learn from a Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Brad, I.; Peț, E.; Popescu, G.; Șmuleac, L. Sustainability of Agritourism Activity. Initiatives and Challenges in Romanian Mountain Rural Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüller, S.; Heiny, J.; Leonhäuser, I.-U. Linking agricultural food production and rural tourism in the Kazbegi district—A qualitative study. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2017, 15, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, O.; Marsat, J.B.; Rambonilaza, T. Tourism and landscapes within multifunctional rural areas: The French case. In Multifunctional Land Use: Meeting Future Demands for Landscape Goods and Services; Mander, K., Ülo, W., Hubert, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishal, J.; Mitra, A. Culinary Narratives and Community Revitalization: The Role of Media in Promoting Sustainable Gastronomy Tourism. In Promoting Sustainable Gastronomy Tourism and Community Development; Ruiz, A.E.J., Bhartiya, S., Bhatt, V., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Anderssson, T.D.; Mossberg, L.; Therkelsen, A. Food and tourism synergies: Perspectives on consumption, production and destination development. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidali, K.L.; Kastenholz, E.; Bianchi, R. Food tourism, niche markets and products in rural tourism: Combining the intimacy model and the experience economy as a rural development strategy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessiere, J.; Tibere, L. Traditional food and tourism: French tourist experience and food heritage in rural spaces. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3420–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Grubor, B.; Banjac, M.; Đerčan, B.; Tešanović, D.; Šmugović, S.; Radivojević, G.; Ivanović, V.; Vujasinović, V.; Stošić, T. The Sustainability of Gastronomic Heritage and Its Significance for Regional Tourism Development. Heritage 2023, 6, 3402–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. Sustainable rural tourism strategies: A tool for development and conservation. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybárová, J.; Rybár, R.; Tometzová, D.; Wittenberger, G. The Use of Cultural Landscape Fragmentation for Rural Tourism Development in the Zemplín Geopark, Slovakia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Prideaux, B.; McShane, C.; Dale, A.; Turnour, J.; Atkinson, M. Tourism development in agricultural landscapes: The case of the Atherton Tablelands, Australia. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandth, B.; Haugen, M.S. Farm diversification into tourism—Implications for social identity? J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, S.; Blackstock, K.; Hunter, C. Agritourism from the perspective of providers and visitors: A typology-based study. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, C.; Cawley, M.; Schmitz, S. The tourist on the farm: A ‘muddled’ image. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava Jimenez, J.A.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G.; Dancausa Millán, M.G. Enotourism in Southern Spain: The Montilla-Moriles PDO. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamarreño-Aramendia, G.; Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz, E. Sustainable Economy and Development of the Rural Territory: Proposal of Wine Tourism Itineraries in La Axarquía of Malaga (Spain). Economies 2021, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A.; Correia, A.; Filipe, J.A. Modelling wine tourism experiences. Anatolia 2019, 30, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancausa Millán, M.G.; Sanchez-Rivas García, J.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G. The Olive Grove Landscape as a Tourist Resource in Andalucía: Oleotourism. Land 2023, 12, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilla-González, J.A.; Murgado-Armenteros, E.M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J. Characterization of Olive Oil Tourism as a Type of Special Interest Tourism: An Analysis from the Tourist Experience Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrastina, P.; Hronček, P.; Gregorová, B.; Žoncová, M. Land-Use Changes of Historical Rural Landscape—Heritage, Protection, and Sustainable Ecotourism: Case Study of Slovak Exclave Čív (Piliscsév) in Komárom-Esztergom County (Hungary). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullino, P.; Larcher, F. Integrity in UNESCO world heritage sites. A comparative study for rural landscapes. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G.; Sánchez-Ollero, J.L.; Dancausa Millán, M.G. Ham Tourism in Andalusia: An Untapped Opportunity in the Rural Environment. Foods 2022, 11, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauniyar, S.; Awasthi, M.K.; Kapoor, S.; Mishra, A.K. Agritourism: Structured literature review and bibliometric analysis. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznajder, M.; Przezbórska, L.; Scrimgeour, F. (Eds.) Agritourism; CABI International: Wallingford, UK, 2009; xv+301 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrerira, D.I.R.; Sánchez-Martín, J.M. La función de las áreas agrícolas en el debate epistemológico sobre el turismo rural, el agroturismo y el agroecoturismo. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2022, 81, 235–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Arroyo, C.; Barbieri, C.; Rozier Rich, S. Defining agritourism: A comparative study of stakeholders’ perceptions in Missouri and North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Tew, C. Perceived Impact of Agritourism on Farm Economic Standing, Sales and Profits; Tourism Travel and Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Arosemena, O. El agroturismo como alternativa económica sostenible post-COVID. In Gobernanza, Comunidades Sostenibles y Espacios Portuarios; Jurado Almonte, J.M., Ed.; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain, 2023; pp. 567–590. [Google Scholar]

- Briceño Núñez, C.E.; Briceño Delgado, M.J.; Montilla Soto, A.D. Estrategias pedagógico-productivas para la valoración del agroturismo en la educación primaria rural. Alternancia—Rev. Educ. Investig. 2022, 4, 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehin Dato Musa, S.F.; Chin, W.L. The contributions of agritourism to the local food system. Consum. Behav. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 17, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler Vayá, F.; San-Martín González, E. Casos de éxito de desarrollo rural en Europa: Una primera aproximación a su aplicabilidad en España. Rev. Int. Econ. Policy 2020, 2, 46–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Barbieri, C. Demystifying Members’ Social Capital and Networks within an Agritourism Association: A Social Network Analysis. Tour. Hosp. 2020, 1, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, A. Trends in wine tourism: The Fladgate group perspective. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falcó, J.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Zaragoza-Sáez, P.; Sánchez-García, E. The effect of wine tourism on the sustainable performance of Spanish wineries: A structural equation model analysis. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2024, 36, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano-Marcolini, C.; D’Auria, A.; Tregua, M. Oleotourism Development in Jaén, Spain. In The Branding of Tourist Destinations: Theoretical and Empirical Insights; Camilleri, M.A., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2018; pp. 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Guerra, I.; Molina, V.; Quesada, J.M. Multidimensional research about oleotourism attraction from the demand point of view. J. Tour. Anal. Rev. De. Tour. Anal. 2018, 25, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.M.; Guillén-Peñafiel, R.; Flores-García, P.; García-Berzosa, M.J. Conceptualization and Potential of Agritourism in Extremadura (Spain) from the Perspective of Tourism Demand. Agriculture 2024, 14, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta-Bejarano, N.; Vásquez-Farfán, B.; Ullauri-Donoso, N. Turismo sensorial y agroturismo: Un acercamiento al mundo rural y sus saberes ancestrales. Rev. Investig. Soc. 2018, 4, 46–58. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/attachments/80534023/download_file?st=MTcxNjM5ODU5NCw3Ny4yMjkuNjUuMTcw&s=swp-splash-paper-cover (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Ravina-Ripoll, R.; Castellano-Álvarez, F.J. The trinomial health, safety and happiness promote rural tourism. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Ley 2/2011, de 31 de Enero, de Desarrollo y Modernización del Turismo de Extremadura. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2011/BOE-A-2011-3179-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Diario Oficial de Extremadura (DOE). Decreto 65/2015, de 14 de Abril, Por el Que se Establece la Ordenación y Sistema de Clasificación de Los Alojamientos de Turismo Rural de la Comunidad Autónoma de Extremadura. Available online: https://doe.juntaex.es/pdfs/doe/2015/740o/15040073.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Junta de Extremadura. Centro de Referencia Nacional de Agroturismo. Available online: https://extremaduratrabaja.juntaex.es/formacion_eshaex_centro_referencia_nacional (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Sánchez-Martín, J.M.; Pérez-Martín, M.N.; Jurado-Rivas, J.C.; Granados-Claver, M.M. Detección de áreas óptimas para la implantación de alojamientos rurales en Extremadura. Una aplicación SIG. Lurralde Investig. Espac. 1999, 22, 367–384. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Martín, J.M.; Rengifo Gallego, J.I.; Martín Delgado, L.M. Tourist Mobility at the Destination Toward Protected Areas: The Case-Study of Extremadura. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.-M.; Gurría-Gascón, J.-L.; García-Berzosa, M.-J. The Cultural Heritage and the Shaping of Tourist Itineraries in Rural Areas: The Case of Historical Ensembles of Extremadura, Spain. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, J.; Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; Del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C.; Castellano-Álvarez, F.J. Cultural Heritage and Tourism Basis for Regional Development: Mapping of Scientific Coverage. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Encuesta de Ocupación en Alojamientos de Turismo Rural (EOTR). Available online: https://ine.es/jaxi/Tabla.htm?tpx=59631&L=0 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- UNESCO. World Heritage Convention. 1986. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/384 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- UNESCO. World Heritage Convention. 1993. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/664 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Ferreira, D.I.R.; Sánchez-Martín, J.-M. Agricultural Landscapes as a Basis for Promoting Agritourism in Cross-Border Iberian Regions. Agriculture 2022, 12, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de España. Denominaciones de Origen e Indicaciones Geográficas Protegidas. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/alimentacion/temas/calidad-diferenciada/dop-igp/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Lopes, C.; Rengifo Gallego, J.; Leitão, J. Os produtos certificados e o desenvolvimento de actividades turísticas: O caso da Estremadura (Espanha) e da Região Centro (Portugal). Finisterra 2022, 57, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.; Leitão, J. Evolución de la Producción y Comercialización de los Productos Regionales Con DOP, IGP Y ETG en Extremadura (España) y Região Centro (Portugal) Entre 2008 y 2018. RPER 2022, 61, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Extremadura. Extremambiente. Available online: http://extremambiente.juntaex.es/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1288&Itemid=459 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Guillén-Peñafiel, R.; Hernández-Carretero, A.M.; Sánchez-Martín, J.-M. Heritage Education as a Basis for Sustainable Development. The Case of Trujillo, Monfragüe National Park and Villuercas-Ibores-Jara Geopark (Extremadura, Spain). Land 2022, 11, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Base Topográfica Nacional 1:100,000 (BTN100). Available online: http://www.ign.es/web/resources/docs/IGNCnig/CBG%20-%20BTN100.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Infraestructura de Datos Espaciales de Extremadura (IDEEX). Ideextremadura.com. Available online: http://www.ideextremadura.com/Geoportal/files/articulos/Mapa_paisaje_Extremadura.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Diario Oficial de Extremadura (DOE). Decreto 205/2012, de 15 de Octubre, Por el Que se Regula el Registro General de Empresas y Actividades Turísticas de Extremadura. Available online: https://doe.juntaex.es/pdfs/doe/2012/2020o/12040226.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Junta de Extremadura. Actividades Turísticas. Available online: https://www.juntaex.es/temas/turismo-y-cultura/actividades-turisticas (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- ESRI. ArcGIS Pro. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/es/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/h-how-spatial-autocorrelation-moran-s-i-spatial-st.htm (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- ESRI. ArcGIS Pro. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/es/pro-app/latest/help/analysis/geostatistical-analyst/how-kernel-interpolation-with-barriers-works.htm (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Sánchez Sánchez-Mora, J.I. El proceso de colonización en Extremadura (1952–1975): Sus luces y sus sombras. In 2015, 2016, La Agricultura y la Ganadería Extremeñas en; Fundación Dialnet: La Rioja, Spain, 2015; pp. 225–240. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, D.I.R.; Sánchez-Martín, J.-M. Shedding Light on Agritourism in Iberian Cross-Border Regions from a Lodgings Perspective. Land 2022, 11, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REDEX. Turismo Rural Extremadura. Recorriendo Extremadura Rural. Available online: https://extremadurarural.es/senderismo/tematica/caminos-naturales/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Sánchez, H.; Mayordomo, S.; Prieta, J.; Cardalliaguet, M. Aves de Extremadura; SEO/BirdLife y Junta de Extremadura: Cáceres, Spain, 2020; p. 255.

- Sánchez-Rivero, M.; Sánchez-Martín, J.-M.; Rodríguez Rangel, M.C. Characterization of Birdwatching Demand Using a Logit Approach: Comparative Analysis of Source Markets (National vs. Foreign). Animals 2020, 10, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diario Oficial de Extremadura (DOE). ORDEN de 24 de Junio de 2019 Por la Que se Declara Fiesta de Interés Turístico de Extremadura la Fiesta “Jornadas Transfronterizas del Gurumelo” en Villanueva del Fresno. Available online: https://doe.juntaex.es/pdfs/doe/2019/1270o/19050378.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Martín-Delgado, L.M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I.; Sánchez-Martín, J.M. La caza como actividad económica en el contexto del modelo de desarrollo endógeno: El territorio de la frontera luso-extremeña como ejemplo. Doc. Geogr. Anal. 2024, 70, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Delgado, L.-M.; Jiménez-Barrado, V.; Sánchez-Martín, J.-M. Sustainable Hunting as a Tourism Product in Dehesa Areas in Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 2022, 14, 10288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Extremadura. Astroturismo. Available online: https://www.turismoextremadura.com/es/ven-a-extremadura/Astroturismo/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Junta de Extremadura. Buenas Noches. Available online: https://extremadurabuenasnoches.com/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Tarazona Valverde, B.Y.; Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Di-Clemente, E. Análisis de las posibilidades gastronómicas del AOVE como base para el diseño de experiencias de oleoturismo en Extremadura. ROTUR 2021, 15, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Regulador Denominación de Origen Aceite de Monterrubio. Aceite de Monterrubio. Available online: http://www.aceitemonterrubiodop.com/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Consejo Regulador Denominación de Origen Aceite de Oliva Virgen Gata-Hurdes. Aceite de Gata-Hurdes. Available online: https://dopgatahurdes.com/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Ley 16/1985, de 25 de Junio, del Patrimonio Histórico Español. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/1985/06/25/16/con (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Ministerio de Cultura, Gobierno de España. Base de Datos de Bienes Inmuebles. Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.es/bienes/cargarFiltroBienesInmuebles.do?layout=bienesInmuebles&cache=init&language=es (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Sánchez, F.; Galeano, S. La Artesanía y su relación con el turismo. Rev. Sci. OMNES 2018, 2, 18–27. Available online: https://www.columbia.edu.py/investigacion/ojs/index.php/OMNESUCPY/article/view/15 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Rivera Mateos, M.; Hernández Rojas, R.D. Microempresas de artesanía, turismo y estrategias de desarrollo local: Retos y oportunidades en una ciudad histórico-patrimonial (Córdoba, España). Estud. Geogr. 2018, 285, 529–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgosa Arcos, F.J. Toros y turismo. Los festejos taurinos declarados como fiestas de interés turístico. In Tauromaquia en la Provincia de Ávila: Historia, Arqueología, Cultura, Arte, Patrimonio, Legislación, Medicina, Veterinaria, Ganaderías, Toreros, Plazas, Tradiciones y Turismo; Fernández Fernández, M., Juárez Pérez, I., Eds.; Diputación de Ávila: Ávila, Spain, 2023; pp. 507–526. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Rodríguez García, J.; Vieira Rodríguez, A. Revisión de la literatura científica sobre enoturismo en España. Cuad. Tur. 2013, 32, 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Regulador de Ribera del Guadiana. Ribera del Guadiana. Available online: http://riberadelguadiana.eu/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Romero, R.H. Rutas del Vino en España: Enoturismo de calidad como motor de desarrollo sostenible. Ambient. Rev. Del. Minist. De. Medio Ambiente 2017, 118, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Encuesta de Ocupación en Alojamientos de Turismo Rural. Metodología. Available online: https://www.ine.es/daco/daco42/ocuptr/meto_eotr.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Rengifo-Gallego, J.I.; Sánchez-Martín, J.M. Análisis de la distribución territorial de los alojamientos rurales y convencionales en los núcleos rurales de Extremadura. An. Geogr. Univ. Complut. 2019, 39, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Extremadura. Extremadura Turismo. Available online: https://www.turismoextremadura.com/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Junta de Extremadura. Plan Estratégico de Turismo Para Extremadura 2010–2015. Available online: https://dehesa.unex.es:8443/bitstream/10662/17141/1/TDUEX_2023_Leal_Solis.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Junta de Extremadura. Estrategia de Turismo Sostenible de Extremadura 2030. II Plan Turístico de Extremadura 2021–2023. Available online: https://www.ugtextremadura.org/sites/www.ugtextremadura.org/files/estrategia_2030_ii_plan_turistico_extremadura_2021-2023.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Junta de Extremadura. Plan Turístico de Extremadura 2017–2020. Available online: https://creex.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Plan_Turistico_de_Extremadura_2017_2020.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Rojo-Ramos, J.; Manzano-Redondo, F.; Mañanas Iglesias, C.; Gamonales, J.M. El Perfil del Empresario de Turismo Activo y Deportes de Aventura en Extremadura. e-Motion Rev. Educ. Mot. Investig. 2021, 17, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis del Campo, V.; Arribas Serrano, N.; Morenas Martín, J. Quality in Active Tourism Services in Extremadura. Apunts Educ. Física Y Deportes 2017, 129, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Extremadura. Extremadura Activa—Directorio de Empresas. Turismo Activo y Otras Actividades en el Medio Natural y Rural. Available online: https://issuu.com/extremadura_tur/docs/guia_turismo_activo (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Rojo-Ramos, J.; Martín-Carmona, R.; Galán-Arroyo, C.; Manzano-Redondo, F.; García-Gordillo, M.Á.; Adsuar, J.C. Trekking Tourism in Spain: Analysis of the Sociodemographic Profile of Trekking Tourists for the Design of Sustainable Tourism Services. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, P.; Murta, L.; Sáez-Padilla, J. La calidad de los servicios de las empresas de turismo activo en Portugal. Cuad. Tur. 2019, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.I.R. El Agroturismo en Territorios de la Frontera Luso-Extremeña: Un Análisis de su Potencial y de su Sostenibilidad. Ph.D. Thesis, Programa de Doctorado en Desarrollo Territorial Sostenible, Universidad de Extremadura, Cáceres, Spain, 16 February 2024. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10662/18475 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Gobierno de Navarra. Decreto Foral 44/2014, de 28 de Mayo, de Agroturismo. Available online: https://www.lexnavarra.navarra.es/detalle.asp?r=33960 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Cánoves Valiente, G.; Herrera Jiménez, L.; Villarino Pérez, M. Turismo rural en España: Paisajes y usuarios, nuevos usos y nuevas visiones. Cuad. Tur. 2005, 15, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.M.; Serrano, M.L.T.; Serrano, V.G. Potenciación del patrimonio natural, cultural y paisajístico con el diseño de itinerarios turísticos. Cuad. Tur. 2014, 34, 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Mogollón, J.M.; Folgado Fernández, J.A.; Campón Cerro, A.M. Oleoturismo en la Sierra de Gata y las Hurdes (Cáceres): Análisis de su potencial a través de un test de producto. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2016, 2, 333–354. [Google Scholar]

- Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G.; Agudo Gutiérrez, E.M. El turismo gastronómico y las denominaciones de origen en el sur de España: Oleoturísmo. Un estudio de caso. Pasos Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2010, 8, 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, C.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I. El enoturismo en Internet. Evaluación de los sitios web de las bodegas de tres rutas del vino de Extremadura (España) y de Alentejo y Região Centro (Portugal). Investig. Tour. 2023, 26, 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Díaz, A.; Rengifo Gallego, J.I.; Leco Berrocal, F. El Agroturismo: Un Complemento Para la Maltrecha Economía de la dehesa. En Turismo e Innovación: VI Jornadas de Investigación en Turismo. Sevilla, 3 y 4 de Julio de 2013. Edición Digital@ tres, 2013. pp. 409–429. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11441/52981 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Guillén-Peñafiel, R.; Hernández-Carretero, A.M.; Sánchez-Martín, J.M. Intangible Heritage of the Dehesa: The Educational and Tourist Potential of Traditional Trades. Heritage 2023, 6, 5347–5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amat-Montesinos, X.; Cortés Samper, C.; Larrosa Rocamora, J.A. Patrimonio territorial y paisajístico de la trashumancia en España. Retos hacia un turismo sostenible y responsable. In TOURISCAPE, I Congreso Internacional Turismo Transversal y Paisaje, Actas; Rosa Jiménez, C., Pié Ninot, R., Nebot Gómez de Salazar, N., Álvarez León, I., Eds.; UMA Editorial; Universidad de Málaga, Instituto IHTT: Málaga, Spain, 2018; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10045/91704 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Oyarvide Ramírez, H.P.; Nazareno Véliz, I.T.; Roldán Ruenes, A.; Ferrales Arias, Y. Emprendimiento como factor del desarrollo turístico rural sostenible. Retos Dir. 2016, 10, 71–93. [Google Scholar]

| Descriptor | |

|---|---|

| Universe | 1095 rural lodgings (Tourism Activities Register, 2023) |

| Sample | 270 |

| Confidence interval | 95% |

| Sampling error | 5.15 |

| Date | 2 January 2023 to 30 December 2023 |

| Type | Random sampling by territorial clusters |

| Questions | Responses | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Genre | Man | 44.9% |

| Woman | 53.3% | |

| Another | 1.8% | |

| Owner’s age group | Up to 30 years | 3.7% |

| From 31 to 40 years old | 10.3% | |

| From 41 to 50 years old | 23.2% | |

| More than 50 years | 62.9% | |

| Seniority in the sector | Less than 5 years | 19.5% |

| From 5 to 10 years old | 22.8% | |

| More than 10 years | 57.7% | |

| Level of education | Primary | 41.5% |

| Media | 14.3% | |

| University students | 44.1% | |

| Language skills | English | 2.15 |

| Frances | 1.68 | |

| Portuguese | 1.50 | |

| Italian | 1.14 | |

| German | 1.09 | |

| Complementary Economic activities | Lodging is the only source of income | 41.5% |

| Income from agriculture or livestock | 8.1% | |

| Income from handicrafts | 1.0% | |

| Revenues from industry | 3.3% | |

| Income from liberal professions | 9.2% | |

| Income from the service sector. | 31.6% | |

| Revenues from various sectors | 5.3% |

| Ask | Reply | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Do you consider that your accommodation falls into the agritourism category? | Yes | 39.0% |

| No | 31.3% | |

| I am not sure | 29.8% | |

| What does agritourism mean to you? | Overnight stay on an agricultural or livestock farm and participation in farming activities. | 27.6% |

| Tourism to learn about the way of life in the rural world | 25.4% | |

| Practice tourism in direct contact with nature | 23.5% | |

| Carrying out activities on an agricultural or livestock farm, even if you spend the night in another place. | 14.0% | |

| Overnight in rural accommodations | 7.4% | |

| Overnight stay on an agricultural or livestock farm | 2.2% | |

| What activity would best define agritourism? | Education and awareness of the values of the rural milieu | 27.6% |

| Participation in agricultural and livestock tasks | 22.8% | |

| The enjoyment of the freedom and tranquility offered by the rural world. | 19.9% | |

| Lodging on agricultural and livestock farms only | 11.8% | |

| I do not know | 8.1% | |

| Rural lodging | 7.0% | |

| Attendance at gastronomic festivals, visits to markets of traditional food products, etc. | 2.2% | |

| Others | 0.6% |

| Ask | Reply | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Do you have an agricultural or livestock farm to complement your lodging? | I have a small orchard and farm to offer as a complementary product. | 13.6% |

| Yes, recreational | 8.8% | |

| Yes, dedicated to agriculture | 14.7% | |

| Yes, dedicated to extensive livestock farming | 9.9% | |

| I do not have a farm, although I could reach an agreement with farmers and ranchers in the area to complement my offer with theirs. | 14.3% | |

| No, and I don’t consider it either. | 38.6% |

| Services | No | Yes |

|---|---|---|

| Bicycle rental | 86.4% | 13.6% |

| Advice on the area | 3.3% | 96.7% |

| Bar/cafeteria | 74.6% | 25.4% |

| Barbecue | 34.9% | 65.1% |

| Cold rooms for game storage | 77.2% | 22.8% |

| Swimming pool | 46.0% | 54.0% |

| Restaurant | 76.1% | 23.9% |

| Free WI-FI | 15.1% | 84.9% |

| Sale of handmade products | 77.9% | 22.1% |

| Sale of local gastronomic products. | 77.2% | 22.9% |

| Sale of own-produced products | 83.8% | 16.2% |

| Nearby Landscape | % Lodging |

|---|---|

| Irrigated crops | 24.6% |

| Rainfed crops | 22.8% |

| Organic crops | 29.0% |

| Wooded dehesas with quercine trees | 62.1% |

| Stone fruit trees | 43.0% |

| Olivares | 53.7% |

| Vineyards | 16.9% |

| Cattle | 43.4% |

| Goats | 30.1% |

| Sheep | 46.0% |

| Swine | 27.6% |

| Reservoirs | 47.4% |

| Rivers or tributaries | 66.9% |

| Activities | No, I Do Not Consider It | No, but I Plan to Offer It | Yes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tasting of local products | 55.1% | 21.3% | 23.5% |

| Monterías | 75.7% | 13.6% | 10.7% |

| Observation of the sky | 40.1% | 29.0% | 30.9% |

| Bird watching | 40.4% | 32.4% | 27.2% |

| Wildlife observation | 46.0% | 30.1% | 23.9% |

| Participation in agricultural tasks | 58.8% | 29.4% | 11.8% |

| Collection of wild products | 50.4% | 29.4% | 20.2% |

| Walking tours to collect wild products | 44.9% | 29.0% | 26.1% |

| 4 × 4 or similar tours | 69.9% | 17.3% | 12.9% |

| Bicycle tours | 55.5% | 23.9% | 20.6% |

| Horseback riding | 62.9% | 18.8% | 18.4% |

| Photographic safaris | 65.1% | 26.1% | 8.8% |

| Visit to ancestral constructions | 52.6% | 28.7% | 18.8% |

| Visits to fighting bulls ranches | 77.2% | 15.4% | 7.4% |

| Visit to producers | 52.2% | 29.4% | 18.4% |

| Visit craftsmen or ancestral trades | 54.0% | 31.6% | 14.3% |

| Visit to wineries | 61.8% | 23.5% | 14.7% |

| Visit to olive oil mills | 53.7% | 30.1% | 16.2% |

| V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 | V9 | V10 | V11 | V12 | V13 | V14 | V15 | V16 | V17 | V18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| V2 | 0.495 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| V3 | 0.471 | 0.486 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| V4 | 0.579 | 0.422 | 0.338 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| V5 | 0.410 | 0.407 | 0.344 | 0.362 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| V6 | 0.496 | 0.756 | 0.574 | 0.436 | 0.349 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| V7 | 0.451 | 0.469 | 0.494 | 0.351 | 0.340 | 0.475 | 1 | |||||||||||

| V8 | 0.450 | 0.590 | 0.338 | 0.476 | 0.353 | 0.533 | 0.447 | 1 | ||||||||||

| V9 | 0.344 | 0.446 | 0.442 | 0.400 | 0.341 | 0.493 | 0.411 | 0.339 | 1 | |||||||||

| V10 | 0.486 | 0.412 | 0.346 | 0.437 | 0.407 | 0.426 | 0.455 | 0.501 | 0.357 | 1 | ||||||||

| V11 | 0.359 | 0.452 | 0.479 | 0.356 | 0.324 | 0.456 | 0.410 | 0.459 | 0.503 | 0.492 | 1 | |||||||

| V12 | 0.463 | 0.561 | 0.456 | 0.316 | 0.337 | 0.599 | 0.462 | 0.462 | 0.470 | 0.413 | 0.518 | 1 | ||||||

| V13 | 0.414 | 0.491 | 0.520 | 0.375 | 0.395 | 0.491 | 0.344 | 0.493 | 0.537 | 0.425 | 0.682 | 0.586 | 1 | |||||

| V14 | 0.343 | 0.332 | 0.429 | 0.317 | 0.244 | 0.378 | 0.473 | 0.417 | 0.385 | 0.527 | 0.418 | 0.467 | 0.412 | 1 | ||||

| V15 | 0.412 | 0.511 | 0.544 | 0.385 | 0.419 | 0.511 | 0.438 | 0.428 | 0.559 | 0.408 | 0.643 | 0.617 | 0.794 | 0.454 | 1 | |||

| V16 | 0.339 | 0.412 | 0.410 | 0.376 | 0.261 | 0.418 | 0.328 | 0.445 | 0.449 | 0.402 | 0.728 | 0.443 | 0.613 | 0.505 | 0.588 | 1 | ||

| V17 | 0.488 | 0.520 | 0.843 | 0.299 | 0.316 | 0.563 | 0.437 | 0.326 | 0.388 | 0.296 | 0.419 | 0.461 | 0.474 | 0.347 | 0.482 | 0.383 | 1 | |

| V18 | 0.502 | 0.804 | 0.523 | 0.432 | 0.398 | 0.667 | 0.503 | 0.577 | 0.473 | 0.468 | 0.449 | 0.588 | 0.454 | 0.374 | 0.508 | 0.413 | 0.476 | 1 |

| 0.443 | 0.505 | 0.471 | 0.387 | 0.350 | 0.505 | 0.426 | 0.450 | 0.458 | 0.431 | 0.569 | 0.536 | 0.554 | 0.420 | 0.526 | 0.398 | 0.476 | 0.506 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Martín, J.M.; Guillén-Peñafiel, R.; Flores-García, P.; García-Berzosa, M.J. Agritourism in Extremadura, Spain from the Perspective of Rural Accommodations: Characteristics and Potential Development from Agrarian Landscapes and Associated Activities. Heritage 2024, 7, 4149-4181. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7080195

Sánchez-Martín JM, Guillén-Peñafiel R, Flores-García P, García-Berzosa MJ. Agritourism in Extremadura, Spain from the Perspective of Rural Accommodations: Characteristics and Potential Development from Agrarian Landscapes and Associated Activities. Heritage. 2024; 7(8):4149-4181. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7080195

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Martín, José Manuel, Rebeca Guillén-Peñafiel, Paloma Flores-García, and María José García-Berzosa. 2024. "Agritourism in Extremadura, Spain from the Perspective of Rural Accommodations: Characteristics and Potential Development from Agrarian Landscapes and Associated Activities" Heritage 7, no. 8: 4149-4181. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7080195

APA StyleSánchez-Martín, J. M., Guillén-Peñafiel, R., Flores-García, P., & García-Berzosa, M. J. (2024). Agritourism in Extremadura, Spain from the Perspective of Rural Accommodations: Characteristics and Potential Development from Agrarian Landscapes and Associated Activities. Heritage, 7(8), 4149-4181. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7080195