Abstract

Caño Roto (Madrid) is one of the most relevant Spanish post-war architectures. Its typological contributions have already been studied within the framework of the so-called “Led Settlements”. This paper proposes a systematic analysis of the evolution of the neighborhood townscape, its most singular characteristic as a critical approach to the CIAM city project. It starts with the photographic documentation, studied through the methodology established by Gordon Cullen and developed, in a systematic way, by Nigel Taylor. The comparative study includes the original published photographs, a sample of photographs from the 2010s, and the shots taken in a new exhaustive documentation campaign. The comparison yields relevant results on the evolution of urban space definers: building volumes, facade composition, pavements or vegetation, and the presence of people in public areas. Several paths are studied to allow an understanding of the overall landscape structure. As a result, the key elements of the townscape of the settlement are identified and valued. The aim of this paper is to provide tools for the preservation of both the architectural and landscape heritage of Caño Roto. In short, thorough knowledge will help residents to become aware of the heritage value of their neighborhood.

1. Introduction

Caño Roto is one of the last episodes in the transition to full modernity in Spanish architecture after the Civil War. Its urban planning and design, architectural morphology, and landscape specificity place it on the border between the assimilation and the crisis of the modern movement. Built under exceptional conditions in post-war Europe, its architectural response to the historical, social, and political context has made it a paradigm of Spanish contemporary heritage. As such, it has been in danger from the beginning of its existence: it has been marginalized, segregated, and reformed by its producing agents as intensely as it has been studied, defended, and supported by the architectural discipline. And, like any relevant urban fact, it has evolved unceasingly along with the conditions of its social environment, with special emphasis on the transformation of the townscape.

According to a better understanding of the evolution of this case, therefore, a study of its environmental transformation is proposed, considering that the urban design has hardly been modified in the last half century; urban fabric does not have any primary element that distinguishes it, beyond its own homogeneous configuration. Through Caño Roto townscape evolution, this paper proposes to systematically study what the key elements of the urban project were and how it has been affected since its origins. That involves a history of more than six decades, from the principles established by architects José Luis Íñiguez de Onzoño and Antonio Vázquez de Castro in their 1957 former project for the “Poblado Dirigido” (Led Settlement), its urban culmination in their 1962 urban design project or the following spontaneous transformations, to the systematic reform of the 1990s and, finally, to its current state.

1.1. Historical Context

From the mid-1940s onwards, the city of Madrid, which was suffering a severe post-war period, began to receive waves of migrants from the interior of the Iberian Peninsula who were leaving their rural environment, even more punished by the famine [1] in search of the opportunities offered by the capital of the state. Its population, which at the beginning of the decade amounted to well over one million inhabitants (1,088,647 in 1940) [2], grew to over one and a half million ten years later (1,618,435 in 1950) [3], and was well over two million in 1960 (2,259,931) [4]. Under these conditions, even the maximum growth forecasts of the General Plan of Madrid [5], which Pedro Bidar had managed to approve by law in 1946, were completely overwhelmed. Moreover, given the economic hardship of the newcomers, the satellite cities planned—yet to be developed—were too far away and isolated from the jobs offered by the capital. Thus, the only real option turned out to be, in most cases, the self-construction of shanty towns or substandard housing on the free land around the city, which the 1945 plan had indicated as “the reserves of green areas of the plans” [6] (p. 20).

The literature of the time [7,8] and later chronicles [9,10] describe a Dantesque image of this misery belt around Madrid. The fraudulent sale of plots of land [6] (p. 11), the intrinsic violence of the social space, and unpresentable living conditions for a state that aspired to integrate into the western block [11], among many other complex factors, reached the extreme around 1954, the year of the enactment of the “Ley de Viviendas de Renta Limitada” (Social Housing Act). However, the migratory flow continued to increase, along with the expansion of shantytowns: three years later, the “Plan de Urgencia Social de Madrid” (Madrid Social Emergency Plan) was passed into law, “which was to allow the construction of 60,000 homes in Madrid” [12] (p. 63). At the end of the day, to tackle the problem, 64,926 public housing units were promoted in the 1950s, 61.2% of the total built between 1940 and 1976, throughout the Franco regime [13] (p. 119).

The first results of these interventions owe their success to the unusual collaboration between two offices of the Francoist apparatus: the “Instituto Nacional de la Vivienda” (National Housing Institute, INV) and the “Comisaría para la Ordenación Urbana de Madrid” (Commissariat for Urban Planning of Madrid) [14]. Heading both institutions were two appointed people who were particularly aware of the political and technical need to address the housing problem in the degraded Madrid suburbs. Luis Valero Bermejo, lawyer in charge of the INV, proposed “state-run” social housing [15] (p. 93); Julián Laguna, architect in charge of the Commissariat for Urban Planning of Madrid, selected a group of young architects from the School of Architecture of Madrid (currently ETSAM-UPM) and allowed them to propose an avant-garde architecture. Laguna organized four types of urban planning actions: “Poblados de Absorción, Poblados Dirigidos, Nuevos Núcleos Urbanos y Barrios Tipo” (Absorption Settlements, Led Settlements, New Urban Areas, and Standard District) [6] (pp. 19–20); of all of them, the first two were only born. The emergency of the situation and the impetus of Valero and Laguna prevailed just for a brief period; then, their leadership was suspended: in 1957, in the wake of the political struggles between different factions of the Francoist apparatus, a major government crisis ended with the creation of the Ministry of Housing under the command of the architect José Luis Arrese. With him, the regime decided to go for the commodification of housing, expressed in his popular play-on-words phrase “no queremos una España de proletarios, sino de propietarios” (we do not want a Spain of proletarians, but of owners) [16].

The Absorption Settlements were the first achievement of the collaboration between Valero and Laguna. Planned to rehouse the shantytown population under a social rental regime, in 1955, a total of eight were completed, with a total of 5000 dwellings. Then, in 1956, Led Settlements were started as social housing for their inhabitants, at the cost price of construction, with a 50-year redemption credit [12] (p. 49). In their first phase, under the aforementioned Social Housing Act, these new neighborhoods were called “Poblados Dirigidos de renta limitada” (limited rent Led Settlements). Their residents—the so-called “domingueros” (Sunday people)—had to pay for at least 20% of the housing through the “prestación personal” (personal provision) of their own labor, i.e., through led self-construction: here, the name of the settlements [6]. This model was implemented in the Led Settlements of Entrevías, Fuencarral, Canillas, Caño Roto, Orcasitas, Manoteras, and Almendrales, all of them significant examples of the return to modernity of Spanish architecture [17]. At the end of 1957, once Valero y Laguna were removed, José Luis Arrese proposed the “Plan de Urgencia Social” (Social Urgency Plan), articulated around private initiative but supported by public subsidies: thus appeared the “Poblados Dirigidos subvencionados” (subsidized Led Settlements), for sale directly by their private promoters and with a 15-year redemption credit [12] (p. 49). Overall, this new plan achieved unprecedented success: between the end of 1957 and 1961, 59,893 housing units were promoted, 45.61% of them by a public administration [13] (p. 126).

1.2. Caño Roto, Past and Present

Caño Roto was one of those “Poblados Dirigidos” (Led Settlements) built by young architects committed to modernism, which at the end of the 1950s was already extremely complex and, in any case, determined to overcome some of the limitations of the first modernist architecture [18]. Both Antonio Vázquez de Castro and José Luis Íñiguez de Onzoño proposed a project of a “neo-realist” character, punctuated by neoplastic references [6] (p. 41) but, at the same time, “organized in small streets and squares, which makes it an architecture, in a certain way, regionalist” [19] (p. 128).

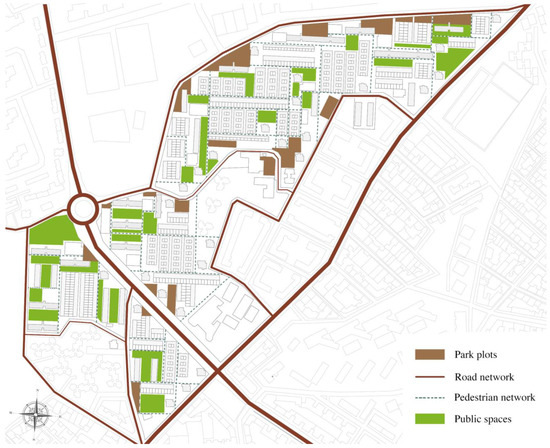

Led Settlement of Caño Roto is located on a slope that descends more than 24 m to the north, a steep downward gradient that is used to create different types of urban spaces. Under the influence of the “mixed development” model [20] (p. 157), the village is characterized by three kinds of spaces, depending on the different housing typologies: the linear six-story blocks, in the lowest area, define and delimit the neighborhood; the towers, in the highest strip, mark and identify a permeable barrier; the rows of single-family houses, finally, extend up and down the hillside. The pedestrian streets that run through the area of single-family houses summarize the domestic urban landscape of Caño Roto. With a width of 3.5 m and a slope of more than 6%, their layout is fragmented into 15-m platforms and flights of stairs that ascend 1.5 m. Thus, every 65 m—between the streets at an even more intimate scale level [21] (p. 57)—there is a perspective defined by the relationship between pavement and facades, in an ascending movement that combines one or two heights in the houses—with a street box of 1:1 or 1:2 proportions—and, in the whole, a total ascent of more than one height in each flight of stairs. This morphology defines on a domestic scale an environment adapted to the original “rural character of the inhabitants of the houses” [14] (p. 62), which is inserted on an urban scale in a rationalized grid (Figure 1). This character is reinforced in the perspectives of these pedestrian streets: if the ascending ones, more intimate, are limited by the topography itself, the descending ones are closed in the perimeter blocks, which recall the metropolitan dimension of the district.

Figure 1.

Structure of the urban space of Caño Roto, according to segregated traffic.

Once the construction of the dwellings was finished, in 1962, the same architects undertook a new project to complete the urban design of the public spaces. Apart from some standardized building details, the greatest emphasis was devoted to landscaping. In the structuring spaces, trees were planted in small groups, which reinforced the landscape sense of the neighborhood: “sometimes they will cover the ends of the blocks, sometimes they will close perspectives, sometimes they will fill the space” [22] (p. 18). In the interior succession of subdivided public spaces, the sense of variety and surprise requires mixed tall vegetation—deciduous and perennial—soft grounds, and a necessary poverty of maintenance, which is resolved in the pedestrian streets by the inhabitants’ own care. At this domestic scale of the common space, landscaped strips of flowerbeds are projected between the street and the walls of the houses, showing where to plant “shrubs of little development, climbers, and perennials”: in some cases, a colorful micro-garden where the splendor of the wisteria balanced the geometrical hollows composition of the facade, tensed the silent vibration of the ochre brickwork walls.

After 1959, “Plan de Estabilización” (Stabilization Economic Plan), supported by U.S. credits, Spain entered the new age called “desarrollismo”, a phase of economic growth that lasted until the 1973 oil crisis, almost in coincidence with the death of General Franco in 1975. During those years, Caño Roto was slowly transformed: with the newly constructed buildings, pending payments, and family survival—apart from some bureaucratic obstacles—the houses did not undergo significant changes. While the vegetation grew, the public space was consolidated, and social life was carried out in an intense sense of belonging to the neighborhood [23]. The organization of the urban fabric, dominated by pedestrian areas, favored casual encounters in a comfortable environment: “in Caño Roto, children can still play in the street” [20] (p. 159). Beyond the misery of its inhabitants or, already in the democratic transition, the problems of citizen insecurity derived from drug trafficking and consumption, the urban landscape projected at the end of the 1950s matured over thirty years into a coherent and singular complex that combines rural nostalgia and its articulation in the growing urban structure of Madrid.

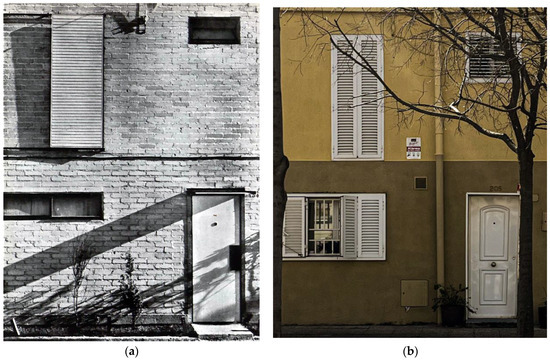

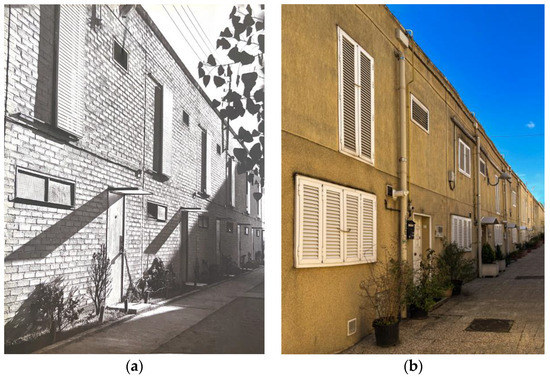

At the end of the 1980s, Spain’s entry into the European Union—then the European Economic Community [24]—and the subsequent economic growth led to an exponential increase in real estate values and, therefore, the consolidation of a patrimonial and financial culture of home ownership [25]. On the other hand, the parallel social evolution was especially significant for the most disadvantaged post-war classes, who radically improved their aspirations and living standards. In this context, the housing conditions of Caño Roto in the early 1960s quickly became obsolete, both in terms of hygiene, facilities, and thermal insulation. Little by little, private renovations in each house replaced glazing, carpentry, locks, façade openings, and even exterior walls “in traditional and even folkloric ways” [19] (p. 128) (Figure 2). This lack of heritage awareness, characteristic of the worst Spanish architectural culture [26], was completed with the comprehensive rehabilitation of the settlement carried out between 1996 and 1997, with “the elimination of almost all the existing vegetation inside” [20] (p. 161), an action that not only did not respect the integrating character of its urban landscape but also disregarded, from the public institution itself, its important heritage value for Madrid’s contemporary culture.

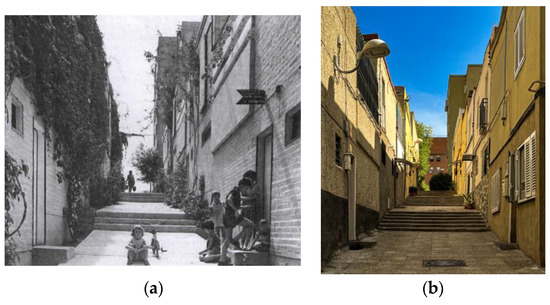

Figure 2.

Private renovations in houses: (a) original state, 1959 [27]; (b) current state, 2023.

2. Materials and Methods

Given the relevant condition of the urban landscape in the heritage value of Caño Roto [15], it is important to analyze in depth its key elements and relationships, its evolution, and, consequently, its characteristics to be preserved. On the other hand, there are several specific research on the residential typology of 1950s social housing, among them the most recent [28], which has developed an interesting graphic methodology. This study also completes a line of research on the architecture and urban planning of the working-class neighborhoods of post-war Madrid, aligned with the so-called “Process Typological Approach” [29] (p. 111) in the study of urban form.

It is considered more appropriate to adapt to the classical analytical approaches on the urban landscape to study the elements of the settlement of Caño Roto corresponding to those “fundamental concepts, serial vision, place and content” [29] (p. 94) that make up the “art of relationship” defined by Gordon Cullen [30]. Other methodologies, such as “classics in urban morphology” [29] (p. 87), especially those focused on the study of the urban environment, have been considered less relevant for two reasons: first, due to the scope of the research, which does not include a sociological study around the common perception of the environment; second, due to the coherent character and the reduced surface of the urban project of the town, which guarantees the “legibility” [31], at least, with respect to three of the five elements pointed out by Lynch: edges, districts, and nodes. On the other hand, the classic study of the townscape has overlapped with the analytical method of urban design as the “art of making or shaping townscapes” [32] (p. 196). In this sense, at least three families of elements, objectifiable beyond the perception of everyone, have been highlighted as “objects of sensation” in Caño Roto: “the Site”, “Objects on the Site”, and “Spaces Created by Objects on the Site” [32] (pp. 199–204). Although Caño Roto was projected more than 40 years before the publication of Taylor’s article, its analytical application is obvious, no doubt due to the team effort implicit in the genealogy of the village.

In the first place, fieldwork has been carried out through pedestrian routes or “paths” [31], based on the reference bibliography of the town. Thus, the archetypal townscape of Caño Roto was documented through general photographs and with special attention to the frames coinciding with the historical photographic series. On the other hand, this documentation was complemented with the most significant images of the urban landscape of the town to generate an extensive photographic archive classified and numbered by frames. Based on this initial documentation, essential studies on the planimetry of the project were carried out by locating key points along three dates to understand the evolution of the urban environment of the neighborhood: 1959–1964, 2010–2013, and 2023. The earliest dates correspond to the first photographic reports published at the time, once the construction was completed [27] and the houses were inhabited [33]. The second series of photographs corresponds to the only report published after the comprehensive rehabilitation of the neighborhood in the 1990s [20]. After that, it was significant to add an exhaustive photographic sample of the current state of the neighborhood, which, moreover, would serve as a basic source for the analysis.

In the second phase of the fieldwork, the primary elements [34]—different “objects of various kinds” [32] (p. 202)—details and singular nuances of buildings, urbanization, and plantations were identified, considering their relevance for the analysis of the urban landscape. Once this map of the territory in its location was completed, it addressed the documentary analysis to relate the partial series of images according to the structure of Caño Roto. The approach is completed with the reading of the apparently anecdotal parts of the settlement, key nevertheless in the environmental characterization of the settlement: secondary elements [34] related to the typological fabric or, around them, “voids created by objects bounding or in space” [32] (p. 204). This last study allows us to understand some of the decisions of the urban project.

The classic townscape analysis method [35], on the other hand, has been applied by means of chronological comparisons: the same shots published in 1959 [27] and 1964 [33] have been located and photographed nowadays to establish a comparison with the current state and, therefore, to have a critical view on the effect of the passage of time. Since these comparisons are concentrated on exact points, key sequences have been chosen for a comprehensive reading of the urban landscape of the neighborhood, verified in a third fieldwork campaign. This set of “serial visions” [30] (p. 17) is the foundation of this part of the analysis and makes it possible to understand at the same point of the investigation several angles of vision, from inside to outside or from the general to the detail.

In short, the study of Caño Roto’s urban landscape has been addressed from three complementary aspects: diachronic analysis, serial vision, and elements of the townscape, both primary and secondary. A critical reflection has been added to suggest a further debate about social considerations.

3. Results

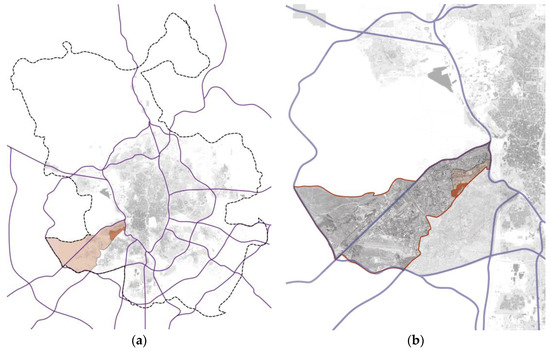

To introduce the urban scale of Caño Roto and its situation in the city of Madrid, a schematic plan of the situation of the “Latina” district is provided, in the northeast corner of which is located the neighborhood of “Los Cármenes”. Within this district, the settlement of Caño Roto occupies the southwest corner, on the border with the neighboring district of “Carabanchel” (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Caño Roto in Madrid: (a) “Latina” District in Madrid urban area; (b) Caño Roto settlement, surrounded by “Los Cármenes” neighborhood, at the northeastern end of “Latina” district.

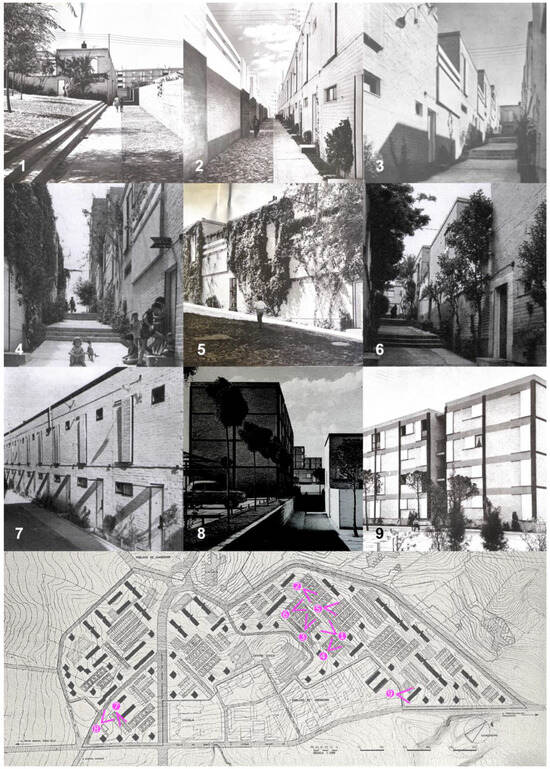

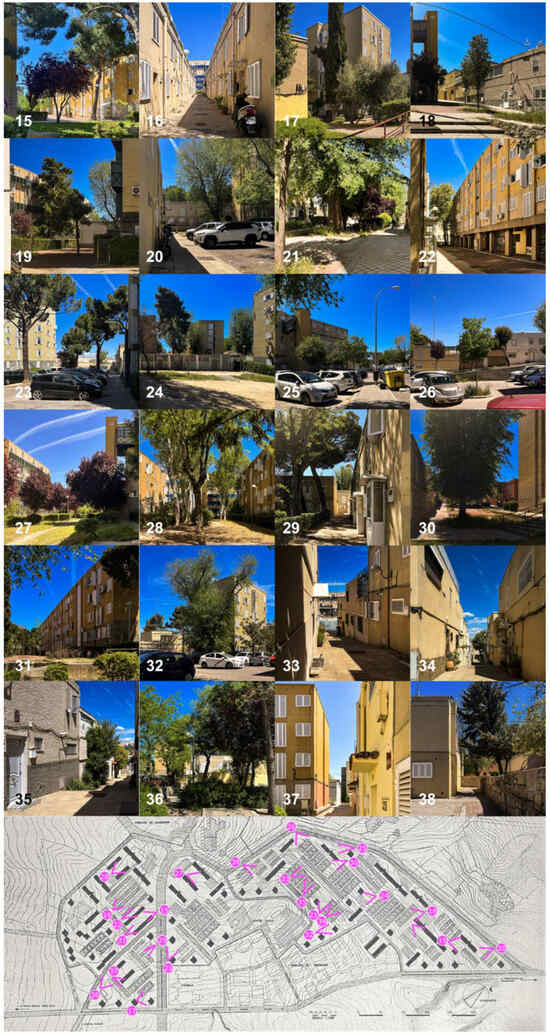

On the plan of the original project are shown the frames of the three photographic series corresponding to the reports carried out in 1959 and 1964—photographs 1 to 9 (Figure 4)—to different shots taken between 2010 and 2013—photographs 10 to 14 (Figure 5)—and, finally, to the field survey of 2023—photographs 15 to 38 (Figure 6). These series have founded different conceptual analyses of the urban landscape of Caño Roto.

Figure 4.

Photographs taken from 1959 (8) [27] to 1964 (1–7; 9) [33].

Figure 5.

Photographs taken from 2010 to 2013 [20].

Figure 6.

Photographs taken in 2023.

3.1. Diachronic Analysis

- Case 1 (Figure 7): The passage of time is shown in the modifications of the buildings, proof that the peasant population that first inhabited the settlement did not share the intentions of its architects: “modernity within a certain order and ambience seeking the seal of the moment” [22] (p. 15). The original rationalist elements are still perceived, although their owners have replaced windows, doors, and details with traditional or even folkloric forms. It is evident that those young architects were influenced by the new European post-war avant-garde, especially the Italian [36]. Those simple and economical forms, however, were replaced by more complex geometries or topical elements, such as paneled doors or vaguely Mediterranean shutters. On the other hand, the exposed brick was replaced by a single-layer plaster due to the insufficient thermal insulation provided by the poor original construction. In the renovation carried out between 1996 and 1997, the vegetation on the façade, which had played a fundamental role in the way of life along the thresholds of the dwellings, also disappeared. At the same time were also eliminated the strips of topsoil next to the basement of the single-family houses, which favored the growth of vegetation and helped increase the coolness of the streets and buildings in the summer months.

Figure 7. Façades: (a) original state, 1964 [33]; (b) current state, 2023.

Figure 7. Façades: (a) original state, 1964 [33]; (b) current state, 2023.

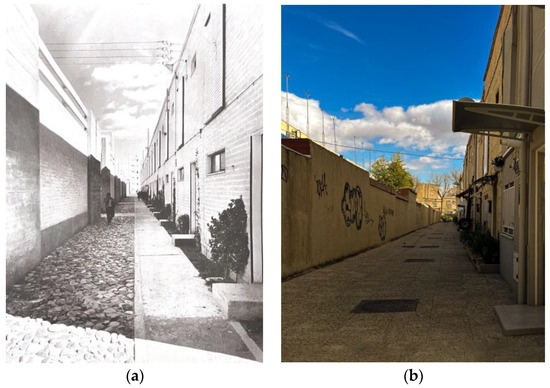

- Case 2 (Figure 8): As in the previous case, the reform of the 1990s put an end to the strips intended for vegetation growth. This timid boundary, moreover, provided the inhabitants with a brief home extension, increasing the few square meters that had been available for building, given the rigors of the budget. In addition, the sliding shutters provided a factor of variety, which, together with the climbing plants, favored the vitalist image of these serial facades: “this eagerness to make such hard architecture a friendly place” [37] (p. 67). There is no doubt, on the other hand, the austerity of the materials, starring the half-foot silica–limestone brick of large format, forces the texture of the walls through “the small shadows that are drawn on all surfaces and that together with the sound of the wind stirring the vegetation, make this dynamic space full of nuances that invite a closer look” [37] (p. 68). All these losses, in short, can be seen in the current monotonous image of these back areas, broken only by the arbitrary nature of the woodwork.

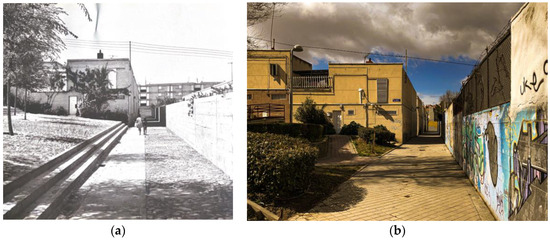

Figure 8. Pedestrian flat streets: (a) original state, 1964 [33]; (b) current state, 2023.

Figure 8. Pedestrian flat streets: (a) original state, 1964 [33]; (b) current state, 2023.

- Case 3 (Figure 9): The layout of the streets of Caño Roto has not been modified, but its materials have, and with them, the image of the neighborhood. This character “where people can feel comfortable inside and outside their homes” [38] (p. 36) was supported by vegetation and paving, much more artisanal and varied in its origins than in the last reform. The domestic condition of the public space favored the expansion of the house toward the exterior: today, on the other hand, the conjunction of the industrial paving and the banal renovations of the houses have blocked the original continuity between the buildings and the streets. In short, the urban fabric, with its narrow pedestrian alleys, maintains intact its capacity to reduce the impact of the urban heat island of Madrid [39]; however, the streets have lost part of their image as a domestic space shared by the community.

Figure 9. Public spaces: (a) original state, 1964 [33]; (b) current state, 2023.

Figure 9. Public spaces: (a) original state, 1964 [33]; (b) current state, 2023.

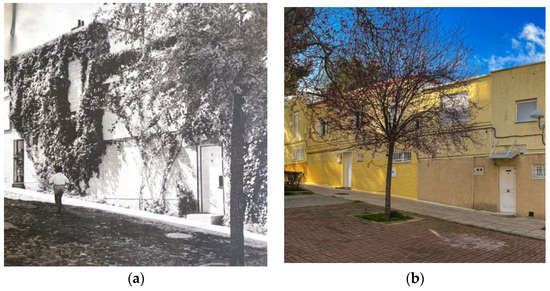

- Case 4 (Figure 10): In the Caño Roto urban project, public spaces constitute a structuring element. Unfortunately, part of the vegetation has been disappearing due to the lack of community involvement in its conservation; meanwhile, the pavement has been modified without a solid criterion. The initial image of the public space, designed “linked to a living tradition” [38] (p. 35) to evoke the squares and small squares of the rural world, has been transformed. In this sense, the original urban design fulfilled a social purpose, as opposed to the current environment, where streets and meeting spaces have been deserted. The passage of time has thus deprived the neighborhood of its maximum identity, the social life for which it was conceived.

Figure 10. Pedestrian sloped streets: (a) original state, 1964 [33]; (b) current state, 2023.

Figure 10. Pedestrian sloped streets: (a) original state, 1964 [33]; (b) current state, 2023.

- Case 5 (Figure 11): Social changes and increased comfort standards have justified the necessary transformation of the building fabric and urban design of Caño Roto. Some stairs in the pedestrian streets have been replaced by ramps to provide universal accessibility, and the vegetation has been replanted to avoid allergies or pests, but the original urban layout remains responsive to the topography and the social context. At the crossroads between the road and the transversal pedestrian streets, the widest meeting spaces appear, like rural Castilian “plazuelas” (small squares). Thus, in the diachronic comparison, it can be seen how this dialogue is preserved, and the void and the buildings continue to form a united whole despite the changes in materials and construction details.

Figure 11. Small squares: (a) original state, 1964 [33]; (b) current state, 2023.

Figure 11. Small squares: (a) original state, 1964 [33]; (b) current state, 2023.

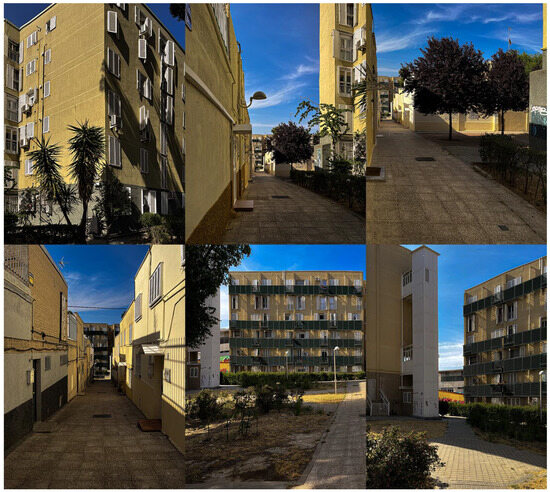

3.2. Serial Vision

- Path 1 (Figure 12): The paths of Caño Roto are a sequence of surprises: from a narrow street, where the slope prevents seeing the end of the perspective, the pedestrian passes to a wider area that functions as a connecting element between different typologies. That change means a subtle articulation between the clusters of single-family homes and high-rise blocks. At the same time, a wide route allows us to understand the repetitive, pedestrian, and orthogonal planning of the settlement, characterized by narrow streets that impose the domestic scale of the dwellings. The morphology of these streets prevents us from imagining the common spaces that lie a few meters beyond, where the small rural squares are evoked as meeting places for the neighborhood. The sum of images induces the repetitive layout of Caño Roto as an expression of its own formal composition and its joint with the rest of the city of Madrid.

Figure 12. Path 1: Surprises in the urban fabric.

Figure 12. Path 1: Surprises in the urban fabric.

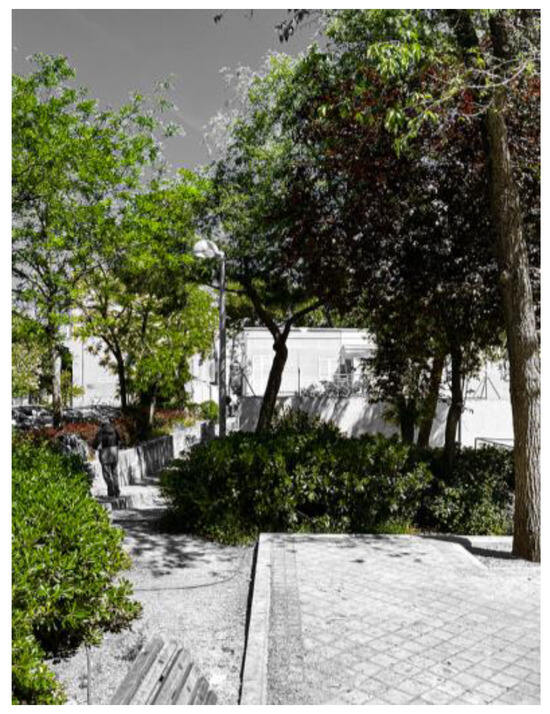

- Path 2 (Figure 13): From its exterior, the first image of Caño Roto allows us to check the initial planning, dominated by the perimeter of high-rise buildings that close and provide intimacy to the urban fabric. When crossing this barrier of blocks, the perspective is immersed in the interior of the group of low houses, in that rural atmosphere—without leaving Madrid—that characterizes the neighborhood. The widenings and small squares are the protagonists of the meeting areas in the articulations between different building typologies: multiple transitions are thus created, nuanced by the diversity of elements, which invite the social integration of the inhabitants.

Figure 13. Path 2: Accessing the neighborhood.

Figure 13. Path 2: Accessing the neighborhood.

- Path 3 (Figure 14): At the bottom of the stairs that run along the slopes of Caño Roto, the exterior of the settlement is barely glimpsed. From these pedestrian streets flanked by low buildings, between the rows of single-family houses, some high-rise buildings appear. In the first flights, the profile of the blocks is confused with the silhouette of their cornices; as ascending, the perspective discerns the nearby figures from the contrasting background, more and more delimited, more and more protagonist. Thus, the architectural typologies configure both an interior landscape and a sensitive memory of the irregularity of the terrain. This contrast between figure and background, between outside and inside, between “here and there” [30] (p. 35) permanently modifies the landscape of the neighborhood. The higher the climb, the more centered the tower and the rows of houses take the stage; at the top of the hill, they emerge completely. There disappear the stairs, which until then had been considered fundamental to the image of the complex. These changing ways of understanding the settlement constitute the structure of its urban landscape, the play between the dramatic topography and the wide plateaus of the encounter.

Figure 14. Path 3: “Here and There”.

Figure 14. Path 3: “Here and There”.

- Path 4 (Figure 15): From end to end of Caño Roto, this path begins at a parking plot in the upper part of the neighborhood, the last point of access by car. From here, the entire route is pedestrian: these wider mixed areas serve to articulate a smooth transition between the different building typologies. Thus, the design succeeds in producing an open space with optimal sunlight for single-family homes. Soft vegetation barriers allow passage and visual connection but support the morphological separation of the urban fabric. These wider spaces appear unexpectedly when wandering through Caño Roto as a spatial relief from the narrow streets flanked by small houses: they are interspersed as esplanades in the manner of the village squares from which the first inhabitants of the settlement came. This broken rhythm produces a certain liberation from the monotony of the serial houses, in addition to avoiding the cul-de-sac closures of the pedestrian streets.

Figure 15. Path 4: Contrasting townscape.

Figure 15. Path 4: Contrasting townscape.

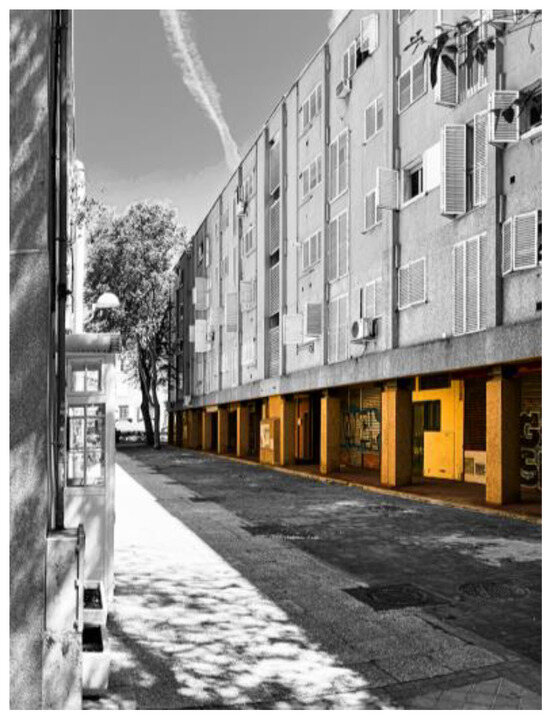

3.3. Elements of the Townscape

3.3.1. Buildings

- Walls: The textures of the walls emphasize the prominence of the building masses but, at the same time, do not camouflage the rhythm of their load-bearing structure. Unfortunately, the original light brick walls of the row houses have been lost; however, in some blocks, the capacity of these elements to configure the urban landscape is still visible (Figure 16).

Figure 16. Walls.

Figure 16. Walls.

- Multiple enclosure: The image shows how the buildings in the foreground form a main street, as opposed to the background, which suggests a gathering space and a secondary access street. This effect is reinforced by the gallery of pillars, which produces a transit space and articulates the street with the square (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Gallery of pillars.

Figure 17. Gallery of pillars.

3.3.2. Other Man-Made Structures

- Pavement: The materials help to differentiate the different functions of the pavement. The one at the entrance to the single-family dwellings varies from the one at the entrance to the residential blocks, as well as the one that articulates the union between the two. The pattern of the pavements also indicates their use, one restricted to pedestrians and the other to vehicles. The shape around the trees changes by means of a small warning strip before topsoil, compacted earth, or other natural pavements (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Pavements.

Figure 18. Pavements.

3.3.3. Trees and Plants

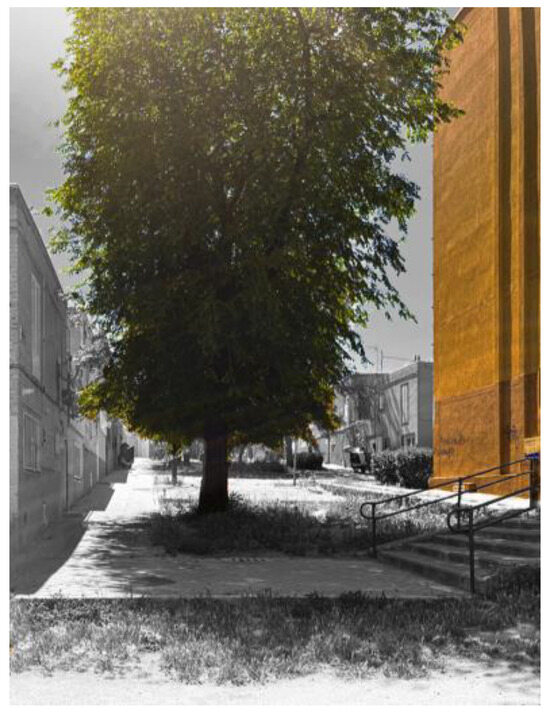

- Trees: Singular trees point out singular perspectives and grow in height next to the vertical of the tower of houses. In contrast, the low houses—more domestic in scale—are relegated to the background behind the tall vegetation (Figure 19).

Figure 19. Singular trees.

Figure 19. Singular trees.

- Intimacy: Although the exterior brick blocks are left out of the scene, we can see how the vegetation forms a ring of protection for the neighborhood: that sense of life and intimacy that still allows us to perceive “a bright and blooming human vigour” [30] (p. 69) (Figure 20).

Figure 20. Vegetation protection.

Figure 20. Vegetation protection.

3.3.4. Spaces Created by Objects on the Site

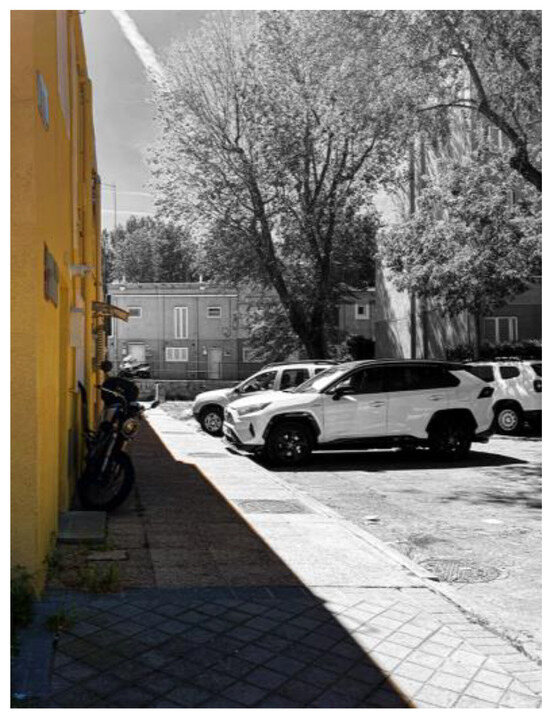

- Silhouette: The contrast between tonalities generated by the mass and shadow of the building defines a separation of spaces and functions. In parking plots, this type of silhouette delimits the territory of the car versus the pedestrian realm; they even imply the residential—the place of privacy—boundaries of the public space (Figure 21).

Figure 21. Silhouettes.

Figure 21. Silhouettes.

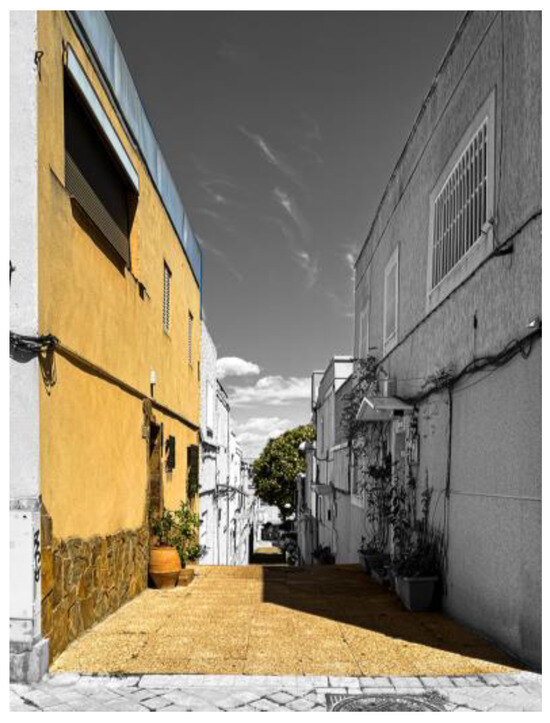

- Proximity: The proximity between buildings in alleys also means functional and spatial aspects. This relation points out the width impossible for car driving, as well as the domestic character of the pedestrian street (Figure 22).

Figure 22. Proximity between buildings.

Figure 22. Proximity between buildings.

- Slopes: The reference to topography structures the spatial memory of the landscape, establishes a reference, and situates perception. In Caño Roto, the meeting places are projected on flat plateaus, while the pedestrian alleys are developed on the slope, giving access to the houses (Figure 23).

Figure 23. Slopes.

Figure 23. Slopes.

3.4. Social Considerations

The residential plan proposed by Juan Laguna for the outskirts of Madrid proposed four phases, stratified according to the social status of the inhabitants. The first two—Absorption Settlements and Led Settlements—were intended for people with very low and irregular incomes or previously nomadic communities. Given that the last two—New Urban Areas and Standard Districts—were never carried out according to the original plans, they were replaced by new neighborhoods promoted by real estate interests, with strong financial support from the state. These developments were home to the great masses of the working-class people, which, as time went by, became the middle class and constituted the socio-economic basis of Spanish consumerist “desarrollismo”.

In this context, Caño Roto—like the rest of the Led Settlements—remained a marginal neighborhood while its wealthier inhabitants moved to more modern spaces, better communicated or with better public facilities. To this day, the neighborhood is the destination of the most underprivileged people, gypsy ethnic groups, and immigrants in the integration process, with a lifestyle different from the rest of the urban environment. Children in Caño Roto can still play in the street, and vehicles do not pass through the squares and parks, but at the same time, its apparent insecurity makes it an unattractive area and hinders the arrival of new neighbors and their social mix.

As a recent interview shows, the night-time journeys from the nearest metro station passed through wastelands and areas where “cars were parked to sleep […] or to have those parties that you put in a circle around the boot of the car”. Caño Roto is perceived, according to the general discourse of the interview, as a neighborhood spatially segregated from its urban environment. Paradoxically, the public space, according to the original urban design, favors a community feeling characterized by the fact that “people take a lot of ownership of the street” [40] (p. 74).

4. Discussion

This article tries to offer solid foundations to generate a critique about the preservation of Caño Roto as a townscape heritage and its contemporary relevance. The settlement is a significant model of the social housing programs promoted by the Franco Regime in Spain as an attempt to solve the problems generated by the massive exodus from the countryside to the cities in the mid-20th century.

From this historical point of view, Caño Roto is a unique case in its context. Compared with the rest of the Led Settlements, it is the only one that proposes an alternative townscape to the CIAM model: the rest, despite their usual medium density, are ordered in a Cartesian system and do not propose such a complex typological mix [28]. In contrast to the profound recovery of the modern movement promoted by the young architects of the 1951 generation [41], the critical proposal of Vázquez de Castro and Íñiguez de Onzoño represents a step forward along the lines of some of the architects of the X Team. External influences, in any case, seem less likely than internal ones: although “a village is not a town” [28] (p. 10), the new villages designed by the “Instituto Nacional de Colonización” (National Institute of Colonisation) were already beginning to be viable models of urban landscape beyond rationalist rigidity, inspired by the natural environment or rural ways of life [42]. The example of Caño Roto, however, had no repercussions on new urban development plans in the rest of Spain after the political and economic changes of the late 1950s. From then on, urban growth would need to be of high or very high density in order to accommodate the massive migration to the big cities. Thus, the townscape of the new neighborhoods will adopt an impoverished version of CIAM urbanism, consolidated by private initiative as “good business” [43] (p. 228).

From a constructive point of view, it has undergone changes practically in its entirety: the stretching brick facades have been totally transformed by insulation layers that offer better living conditions, although they are incompatible with the preservation of the initial image. The communication cores of the high-rise buildings have been renovated to adapt them to comfort standards, free-standing elevators have been included to allow universal accessibility, and stairwells have been closed to comply with current regulations and increasing safety. In all the buildings, doorways have been added that break with the initial idea of community, where the dwelling and the outdoor space form a single place. The initial appearance of the single-family dwellings adapted to the change in elevation has also been disturbed by the disappearance in repeated situations of the upper terrace to enlarge the house, as well as the change in the shapes and arrangement of the windows and doors to seek comfort and meet the needs of the inhabitants.

In the globalized world, the need to evoke the rural world has been lost, even the need to take root in a local memory or culture of reference. Caño Roto, however, continues to offer the tranquillity of pedestrian spaces in a spacetime island out of the constant and excessive growth of the city of Madrid. In those Led Settlements, rootless even to the urbanity of the surrounding working-class districts, its first inhabitants gradually achieved greater social stability and moved to new, more modern neighborhoods. Since then, the villages have hosted the most disadvantaged social groups: immigrants or people of ethnic backgrounds alien to the urban environment. Indeed, children in Caño Roto can still play in the street, and vehicles do not pass through the squares and parks, but at the same time, their low per capita income prevents a collective concern for the conservation of their townscape; what is more, the risk of social exclusion of most of the community hinders their regard of this heritage.

In short, the cultural heritage represented by the Caño Roto townscape has been at risk for decades, as even the latest institutional intervention shows. Given its historical and cultural value, there is an urgent need for disciplinary reflection and, thus, a public commitment to propose a whole preservation and intervention project able to withstand the new contemporary ways of life of the community. Hence, urban design can provide an opportunity to solve the double problem, human and patrimonial, that arises in Caño Roto and in many other notorious examples of the best contemporary architecture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.A.; Methodology, A.C.A.; Validation, A.C.A. and M.M.; Formal analysis, A.C.A., M.G.M. and M.M.; Investigation, A.C.A. and M.G.M.; Resources, A.C.A. and M.G.M.; Writing – original draft, A.C.A. and M.G.M.; Writing—review & editing, M.M.; Supervision, A.C.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Madrid Government (Comunidad de Madrid-Spain) under the Multiannual Agreement with Universidad Politécnica de Madrid in the line Excellence Programme for University Professors, in the context of the V PRICIT (Regional Programme of Research and Technological Innovation).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Del Arco Blanco, M.A. Los «Años del Hambre»: Historia y Memoria de la Posguerra Franquista; Marcial Pons: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Censo de 1940. Available online: https://www.ine.es/inebaseweb/treeNavigation.do?tn=92639 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Censo de 1950. Available online: https://www.ine.es/inebaseweb/treeNavigation.do?tn=92668&tns=125205#125205 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Censo de 1960. Available online: https://www.ine.es/inebaseweb/treeNavigation.do?tn=92681&tns=126756#126756 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Sambricio, C. Madrid: Ciudad-Región. De la Ciudad Ilustrada a la Primera Mitad del Siglo XX; Comunidad de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Galiano, L. Madrid 1956. La historia de los poblados. In La Quimera Moderna; Hermann Blume: Madrid, Spain, 1989; pp. 9–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Ferlosio, R. El Jarama; Ediciones Destino: Barcelona, Spain, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Santos, L. Tiempo de Silencio; Seix Barral: Barcelona, Spain, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Umbral, F. Trilogía de Madrid; Seix Barral: Barcelona, Spain, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Goytisolo, J. Coto Vedado; Seix Barral: Barcelona, Spain, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Del Arco Blanco, M.A. «Morir de hambre». Autarquía, escasez y enfermedad en la España del primer franquismo. Pasado Y Memoria. Rev. De Hist. Contemp. 2005, 5, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambricio, C. La vivienda en Madrid, de 1939 al Plan de Vivienda Social, en 1959. In La Vivienda en Madrid en la Década de Los 50. El Plan de Urgencia Social; Electa: Madrid, Spain, 1999; pp. 13–84. [Google Scholar]

- López de Lucio, R. El Plan de Urgencia Social de Madrid de 1957. Génesis y razones de la forma de ciudad en los años 50′. In La Vivienda en Madrid en la Década de Los 50. El Plan de Urgencia Social; Electa: Madrid, Spain, 1999; pp. 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban Maluenda, A. Poblados dirigidos de Madrid. VPOR2 Rev. De Vivienda 2009, 6, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo del Olmo, J.M. El Poblado Dirigido de Caño Roto: Dialéctica Entre Morfología Urbana y Tipología Edificatoria. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2014. Available online: https://doi.org/10.20868/UPM.thesis.32704 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Arrese, J.L. No queremos una España de proletarios, sino de propietarios. ABC 1959, 2, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Cabrero, G. El Moderno en España; Tanais: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Montaner, J.M. Después del Movimiento Moderno. Arquitectura de la Segunda Mitad del Siglo XX; Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Isasi, J. Los poblados en el urbanismo y la vivienda de la posguerra. In La Quimera Moderna; Hermann Blume: Madrid, Spain, 1989; pp. 95–131. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo del Olmo, J.M. El espacio público como elemento estructurante del proyecto urbano. Una mirada retrospectiva hacia el poblado dirigido de Caño Roto. In Poblado Dirigido de Caño Roto; Cánovas, A., Ed.; Centro de Estudios y Experimentación de Obras Públicas: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Blanes Pérez, E. La topografía como sistema de articulación urbana. Del plano al territorio. In Poblado Dirigido de Caño Roto; Cánovas, A., Ed.; Centro de Estudios y Experimentación de Obras Públicas: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez de Castro, A.; Iñiguez de Onzoño, J.L. Memoria del Proyecto reformado. In Poblado Dirigido de Caño Roto; Cánovas, A., Ed.; Centro de Estudios y Experimentación de Obras Públicas: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mariño, H.; Caño Roto Social Club. Público2022, 26 September. Available online: https://www.publico.es/culturas/cano-roto-social-club.html (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- History of the European Union. Available online: https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/history-eu_en (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Dioni, J. La España de las Piscinas; Arpa Editores: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, A. España Fea. El Caos Urbano, el Mayor Fracaso de la Democracia; Debate: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Iñiguez de Onzoño, J.L.; Vázquez de Castro, A. Poblado Dirigido de Caño Roto. Arquitectura 1959, 8, 2–17. Available online: https://www.coam.org/es/fundacion/biblioteca/revista-arquitectura-100-anios/etapa-1959-1973/revista-arquitectura-n8-Agosto-1959 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Cánovas, A.; Espegel, C.; Lapuerta, J.M.; Feliz, S. Atlas de los Poblados Dirigidos: Madrid, 1956–1966; Ediciones Asimétricas: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, V.M. The Study of Urban Form: Different Approaches. In Urban Morphology; Springer International: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 87–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, G. The Concise Townscape, 2nd ed.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N. The elements of townscape and the art of urban design. J. Urban Des. 1999, 4, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez de Onzoño, J.L.; Vázquez de Castro, A. Poblado dirigido de Caño Roto (1ª y 2ª Fases) 1606 Viviendas. Hogar Y Arquit. 1964, 54, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. L’architettura Della Città; Marsilio: Padova, Italy, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, G. Townscape; Architectural Press: London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, D. Neorealist Architecture: Aesthetics of Dwelling in Postwar Italy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lazcano, J. Lazcano, J. La construcción de Caño Roto. In Poblado Dirigido de Caño Roto; Cánovas, A., Ed.; Centro de Estudios y Experimentación de Obras Públicas: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, C. El poblado de Caño Roto. Hogar Y Arquit. 1964, 54, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Román Lόpez, E.; Gόmez Muñoz, G.; De Luxán García de Diego, M. Urban heat island of Madrid and its influence over urban thermal comfort. In Sustainable Development and Renovation in Architecture, Urbanism and Engineering; Mercader-Moyano, P., Ed.; Springer International Publising: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Manso, M. Evolución del Paisaje Urbano en Caño Roto: Los Poblados Dirigidos. Final Degree Project. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Baldellou, M.A. Sáenz de Oíza, Arquitecto; Diseño: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Centellas, M. Los Pueblos de Colonización de Fernández del Amo. Arte, Arquitectura y Urbanismo; Fundación Caja de Arquitectos: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Terán, F. Historia del Urbanismo en España, 3rd ed.; Ediciones Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 1983. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).