Polychrome Marbles in Christian Churches: Examples from the Antependium of Baroque Altars in Apulia (Southern Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Historical Use of Decorative Polychrome Marbles

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

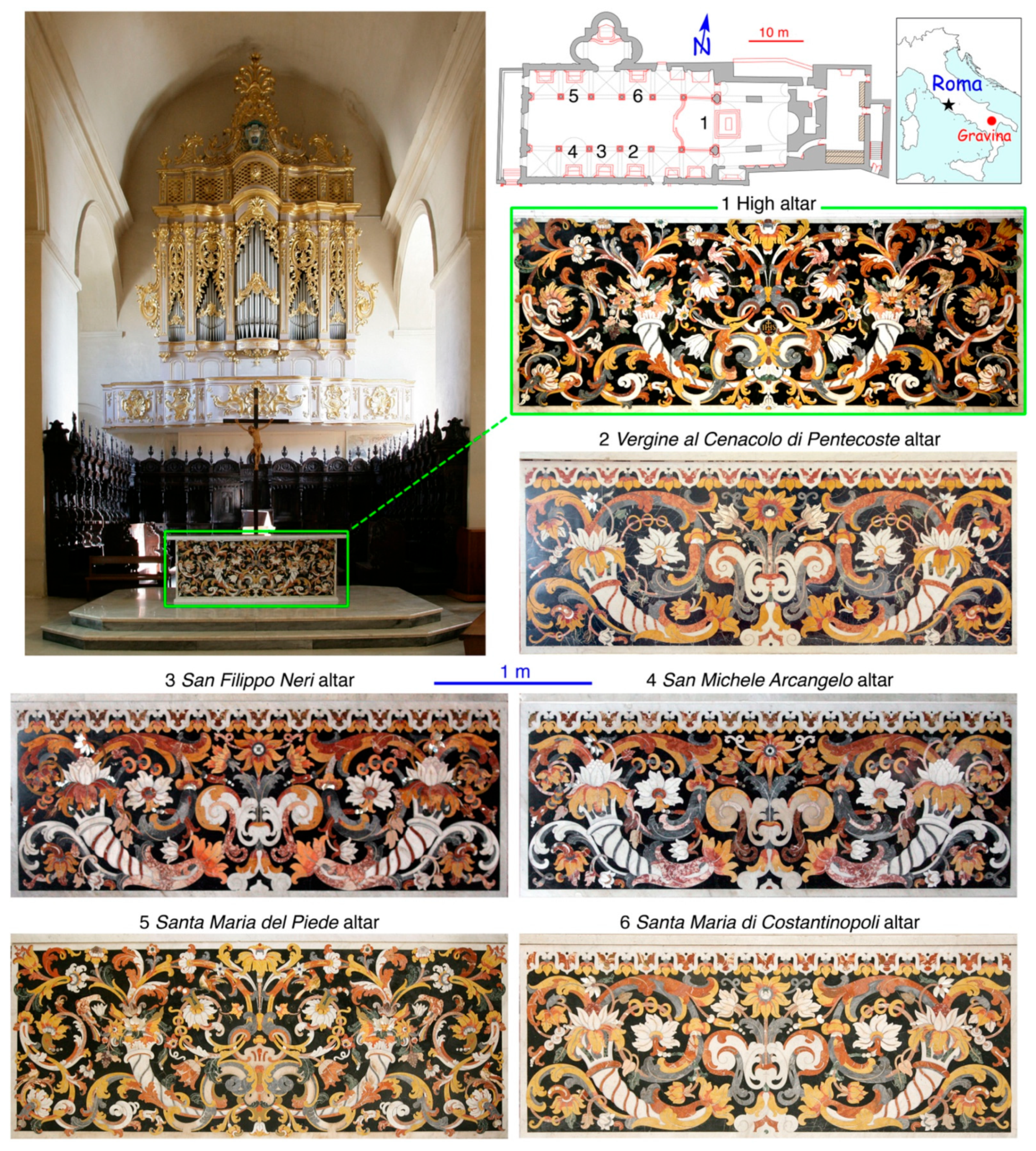

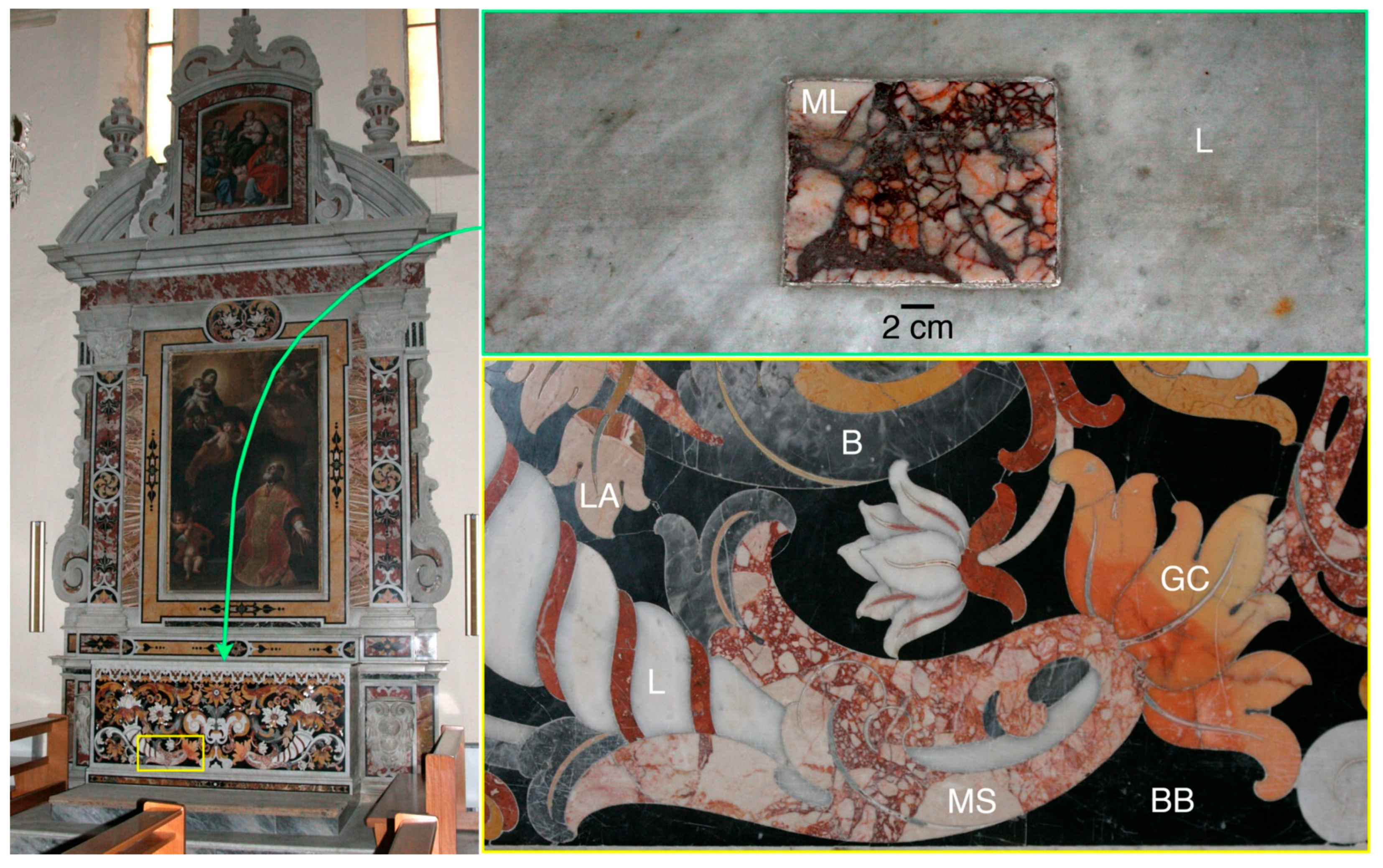

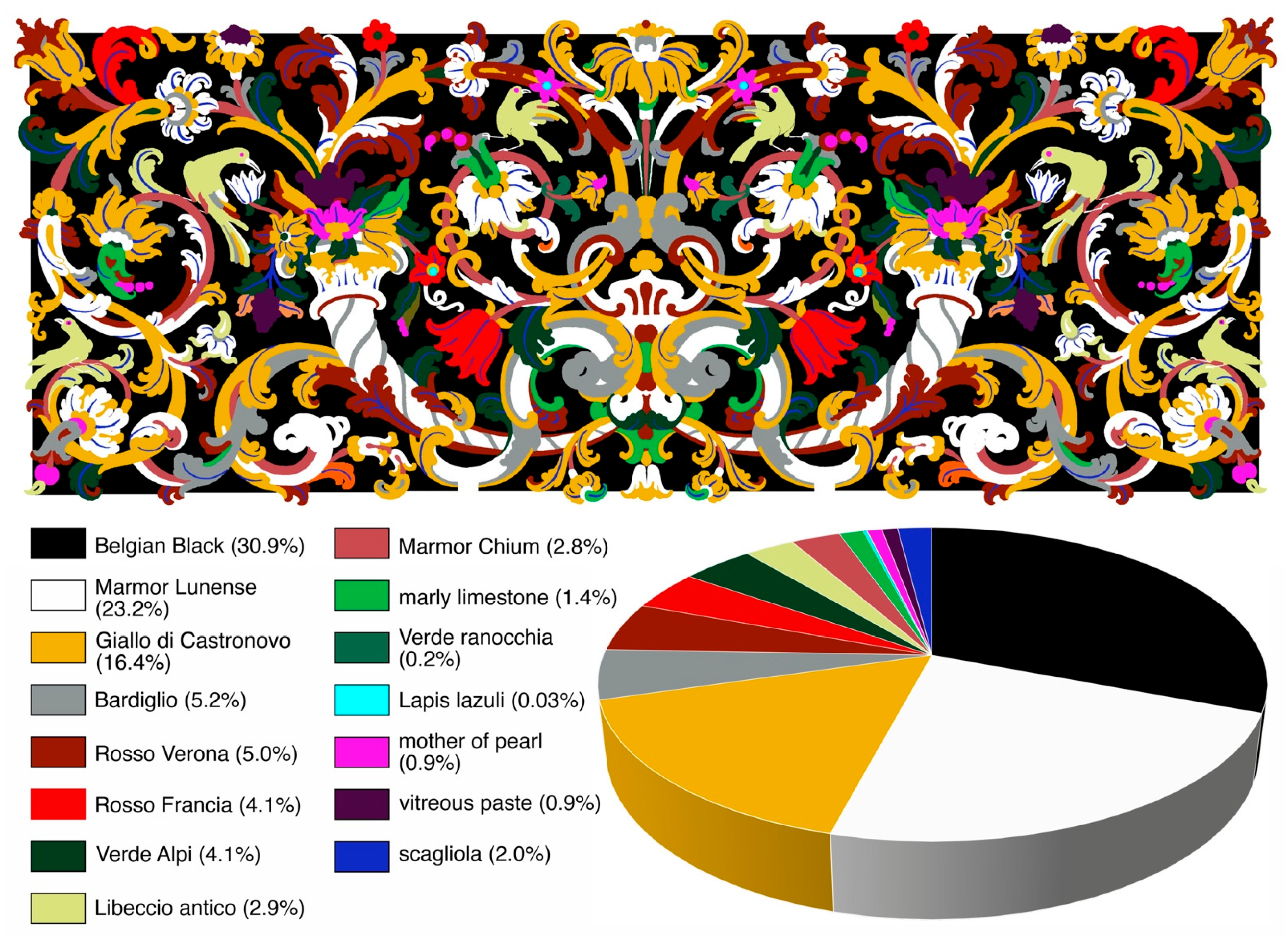

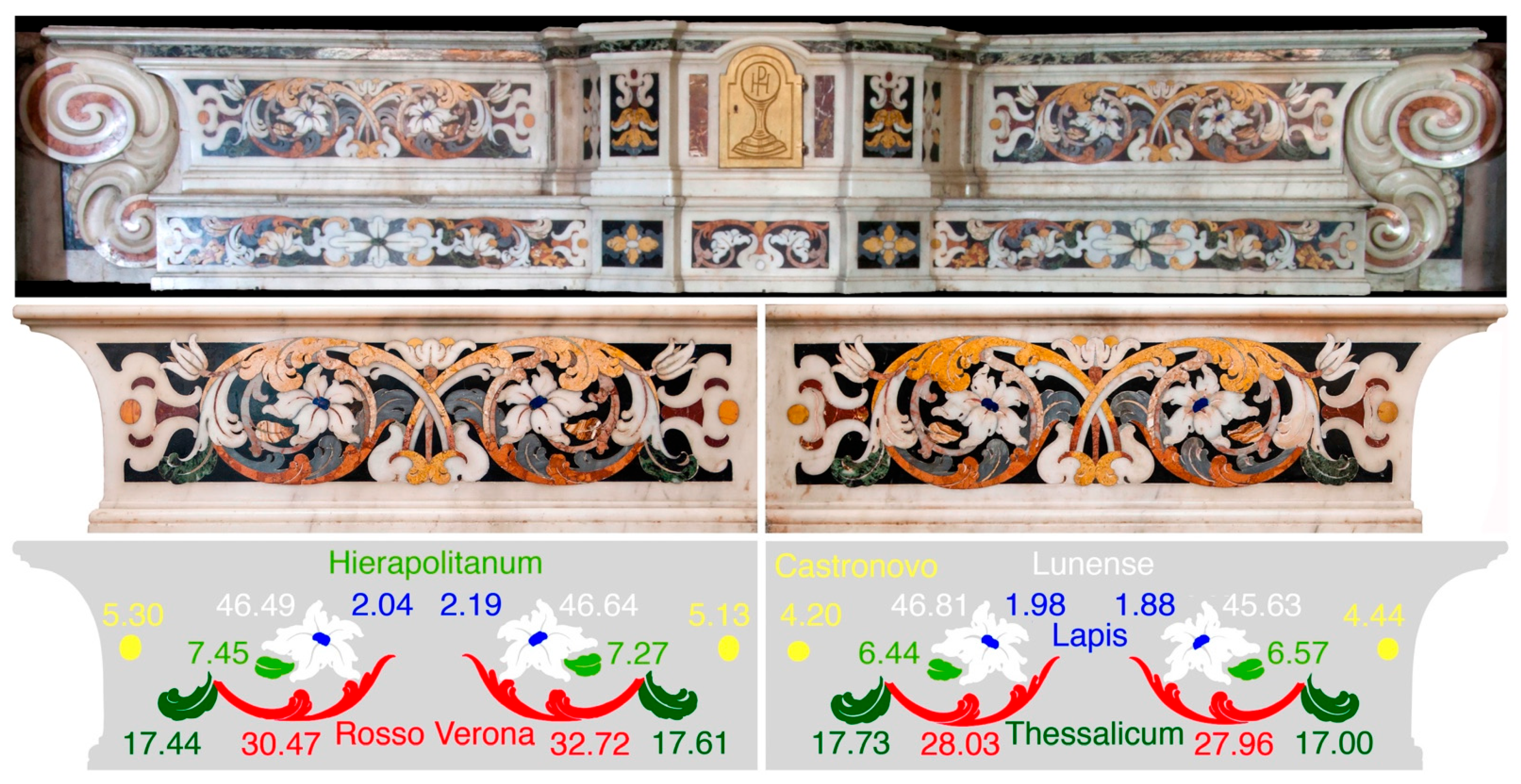

3.1. The Altars of the Gravina Cathedral

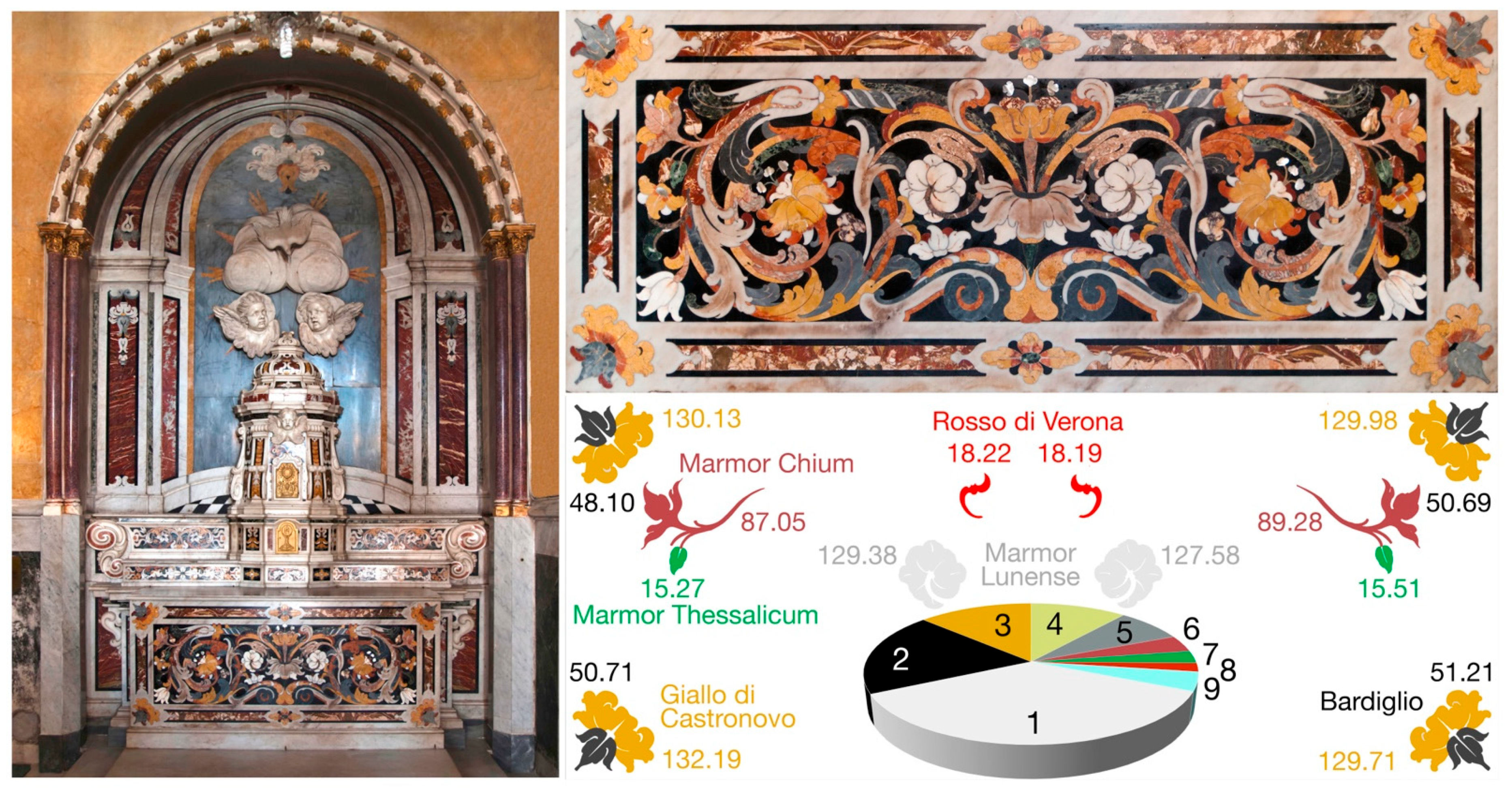

3.2. The Altars of the Cathedral of Altamura

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corsi, F. Delle Pietre Antiche; Dalla Tipografia Salviucci: Rome, Italy, 1833. [Google Scholar]

- Gnoli, R. Marmora Romana; Ed. rived. e ampliata, [Nachdr.]; Edizioni dell’Elefante: Rome, Italy, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Borghini, G. Marmi Antichi; De Luca Editori d’Arte: Rome, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- De Nuccio, M.; Ungaro, L.; Pensabene, P.; Lazzarini, L. (Eds.) I Marmi Colorati della Roma Imperiale; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, S. The Standard of Ur; Object in focus; British Museum Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mageed, E.A.; Ibrahim, S.A. Ancient Egyptian Colours as a Contemporary Fashion. J. Int. Colour Assoc. 2012, 9, 32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Saul, J.M. Flickering Flames over the Libyan Desert? Int. Geol. Rev. 2019, 61, 1340–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, L.; Sangati, C. I Più Importanti Marmi e Pietre Colorati Usati Dagli Antichi. In Pietre e Marmi Antichi—Natura, Caratterizzazione, Origine Storia d’Uso, Diffusione, Collezionismo; Lazzarini, L., Ed.; CEDAM: Padova, Italy, 2004; pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarini, L. I Marmi e le Pietre del Pavimento Marciano. In Il Manto di Pietra di San Marco a Venezia. Storia, Restauri, Geometrie del Pavimento; Vio, E., Ed.; Cicero: Venezia, Italy, 2012; pp. 51–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hirt, A.M. Imperial Mines and Quarries in the Roman World: Organizational Aspects, 27 BC–AD 235; Oxford classical monographs; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Calvano, C.D.; Van Der Werf, I.D.; Palmisano, F.; Sabbatini, L. Revealing the Composition of Organic Materials in Polychrome Works of Art: The Role of Mass Spectrometry-Based Techniques. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 6957–6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanni, A. Interraso marmore (Plin., N.H., 35, 2): Esempi della tecnica decorativa a intarsio in età romana. Studi Misc. 1998, 31, 259–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ribechini, E.; Orsini, S.; Silvano, F.; Colombini, M.P. Py-GC/MS, GC/MS and FTIR Investigations on LATE Roman-Egyptian Adhesives from Opus Sectile: New Insights into Ancient Recipes and Technologies. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 638, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasculli Ferrara, D. L’Arte dei Marmorari in Italia Meridionale: Tipologie e Tecniche in Età Barocca; Atlante tematico del Barocco in Italia; De Luca Editori d’Arte: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Lachenal, L. Spolia: Uso e Reimpiego dell’Antico dal III al XIV Secolo; Biblioteca di archeologia; Longanesi: Milan, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Acquafredda, P.; Fioretti, G. Aspetti Petrografici Degli Altari in Marmi Policromi in Puglia. In Viridarium Novum Studi di Storia dell’Arte in onore di Mimma Pasculli Ferrara; Fonseca, C.D., Di Liddo, I., Eds.; De Luca Editori d’Arte: Rome, Italy, 2020; pp. 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Pasculli Ferrara, D.; Ressa, A. Il Cappellone di San Cataldo: Il Trionfo di Giuseppe Sanmartino e dei Marmi Intarsiati Nella Cattedrale di Taranto; De Luca Editori d’Arte: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, L. The 19th Century Corsi Collection of Decorative Stones: A Resource for the 21st Century? Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2010, 333, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, R. Cristalli, Fossili e Marmi Antichi della Sapienza: Collezioni Storiche dei Musei di Scienze della Terra e Unità d’Italia; Nuova Cultura: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mielsch, H.; Antikenmuseum Berlin (Eds.) Buntmarmore aus Rom im Antikenmuseum Berlin; Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz: Berlin, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Giardini, G.; Colasante, S. Collezioni di Pietre Decorative Antiche «Federico Pescetto» e «Pio de Santis»; Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dolci, E.; Cioffarelli, A. Marmi Antichi da Collezione la Raccolta Grassi del Museo Nazionale Romano; Dolci, E., Nista, L., Eds.; Museo Civico del Marmo Carrara: Pisa, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pensabene, P.; Bruno, M.; Stuto, G. (Eds.) Il Marmo e Il Colore: Guida Fotografica, i Marmi della Collezione Podesti; L’Erma di Bretschneider: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Napoleone, C. Il Collezionismo dei Marmi e Pietre Colorate dal Secolo XVI al Secolo XIX. In Marmi Antichi; Borghini, G., Ed.; Edizioni de Luca: Rome, Italy, 1992; pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fioretti, G.; Acquafredda, P.; Monno, A.; Montenegro, V.; Francescangeli, R. Roman Marble Collections in the Earth Sciences Museum of the University of Bari (Italy): A Valuable Heritage to Support Provenance Studies. Heritage 2023, 6, 4054–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, F.; Lazzarini, L. An Updated Petrographic and Isotopic Reference Database for White Marbles Used in Antiquity. Rend. Lincei 2015, 26, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, F.; Nestola, F. An Innovative Approach for Provenancing Ancient White Marbles: The Contribution of X-ray Diffraction to Disentangling the Origins of Göktepe and Carrara Marbles. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brilli, M.; Antonelli, F.; Giustini, F.; Lazzarini, L.; Pensabene, P. Black Limestones Used in Antiquity: The Petrographic, Isotopic and EPR Database for Provenance Determination. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 994–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, F.; Lazzarini, L.; Cancelliere, S. ‘Granito del foro’ and ‘Granito di Nicotera’: Petrographic features and archaeometric problems owing to similar appearance. Archaeometry 2010, 52, 919–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, L.; Antonelli, F. L’identificazione Del Marmo Costituente Manufatti Antichi. In Pietre e Marmi Antichi—Natura, Caratterizzazione, Origine Storia d’Uso, Diffusione, Collezionismo; Lazzarini, L., Ed.; CEDAM: Padova, Italy, 2004; pp. 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, F.; Lazzarini, L.; Cancelliere, S.; Dessandier, D. On the white and coloured marbles of the Roman town of Cuicul (Djemila, Algeria). Archaeometry 2009, 52, 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, D.; Bruno, M.; Prochaska, W.; Yavuz, A.B. A Multi-Method Database of the Black and White Marbles of Göktepe (Aphrodisias), Including Isotopic, EPR, Trace and Petrographic Data: The Black and White Marbles of Göktepe (Aphrodisias). Archaeometry 2015, 57, 217–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biricotti, F.; Severi, M. A Non-Destructive Methodology for the Characterization of White Marble of Artistic and Archaeological Interest. J. Cult. Herit. 2004, 5, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniatis, Y.; Tambakopoulos, D.; Lazzarini, L.; Sturgeon, M.C. Provenance Investigation of Three Marble Relief Sculptures from Ancient Corinth: New Evidence for the Circulation of the White Marble from Mani. Archaeometry 2021, 63, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioretti, G.; Acquafredda, P.; Calò, S.; Cinelli, M.; Germanò, G.; Laera, A.; Moccia, A. Study and Conservation of the St. Nicola’s Basilica Mosaics (Bari, Italy) by Photogrammetric Survey: Mapping of Polychrome Marbles, Decorative Patterns and Past Restorations. Stud. Conserv. 2020, 65, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracci, S.; Vettori, S.; Cantisani, E.; Degano, I.; Galli, M. The Ancient Use of Colouring on the Marble Statues of Hierapolis of Phrygia (Turkey): An Integrated Multi-Analytical Approach. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, D.; Brilli, M.; Bruno, M. The properties and identification of marble from Proconnesos (Marmara Island, Turkey): A new database including isotopic, EPR and petrographic data. Archaeometry 2008, 50, 747–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquafredda, P. Marmi policromi nella Cattedrale di Altamura: Aspetti petroarcheometrici. Geol. Territ. 2015, 12, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kullerud, G.; Yoder, H.S. Pyrite stability relations in the Fe-S system. Econ. Geol. 1959, 54, 533–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.J. Pyrite-pyrrhotine redox reactions in nature. Mineral. Mag. 1986, 50, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, R.V.; Gillham, R.W.; Reardon, E.J. Pyrite oxidation in carbonate-buffered solution: 1. Experimental kinetics. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1988, 52, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, L. Archaeometric aspects of white and coloured marbles used in antiquity: The state of the art. Period. Mineral. 2004, 73, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- May-Crespo, J.; Martìnez-Torres, P.; Quintana, P.; Alvarado-Gil, J.J.; Vilca-Quispe, L.; Camacho, N. Study of the Effects of Heating on Organic Matter and Mineral Phases in Limestones. J. Spectrosc. 2021, 2021, 9082863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigroux, M.; Sciarretta, F.; Eslami, J.; Beaucour, A.-E.; Bourgès, A.; Noumowé, A. High temperature effects on the properties of limestones: Post-fire diagnostics and material’s durability. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G. I Maestri Marmorari Napoletani della Seconda Metà del Settecento nel Cosentino. Alcuni Documenti Sulla Committenza degli Altari. Arch. Stor. Calabr. Lucania 2015, 81, 87–135. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/21810490/_I_maestri_marmorari_napoletani_della_seconda_met%C3%A0_del_Settecento_nel_Cosentino_Alcuni_documenti_sulla_committenza_degli_altari_in_Archivio_Storico_per_la_Calabria_e_la_Lucania_LXXXI_2015_pp_87_135_ISSN_0004_0355?uc-g-sw=19888868 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Acquafredda, P.; Clemente, M.; Susca, M. I marmi policromi degli altari della Cattedrale di Gravina. In La Cattedrale di Gravina nel Tempo; Lorusso, G., Calculli, L., Clemente, M., Eds.; LAB Edizioni, Altamura: Bari, Italy, 2013; pp. 245–261. ISBN 978-88-97796-09-1. [Google Scholar]

| Common Name | Petrographic Description | Provenance | Reference Representative Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bardiglio | Dark and pale grey marble | Apuan Alps, Carrara, Italy |  |

| Belgian Black | Black limestone with carbonaceous components | Golzinne, Gembloux, Belgium |  |

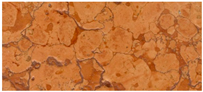

| Broccatello | Red and yellow fossiliferous limestone | Tortosa, Sapin |  |

| Giallo di Castronovo | Yellow limestone with dispersed goethite and dark and thin veins | Castronovo, Palermo, Italy |  |

| Lapis lazuli | metamorphic rock rich in lazurite | Sar-e Sang, Badakhshan, Afghanistan |  |

| Libeccio antico | Fossiliferous, brecciated, and very variable-colored limestone | Custonaci, Trapani, Italy |  |

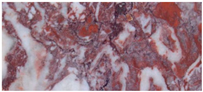

| Marmor Chalcidium | Pinkish red metalimestone with large white veins | Nea Psara (ancient Eretria), Greece |  |

| Marmor Chium | Limestone fault breccia with variable color, mainly with red cement | Chios Island, Greece |  |

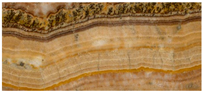

| Marmor Hierapolitanum | Fine-grained banded, compact calcite travertine | Pamukkale (ancient Hierapolis), Turkey |  |

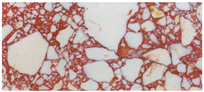

| Marmor Luculleum | Carbonate metabreccia with variable-colored clasts and black matrix and cement | Teos, Turkey |  |

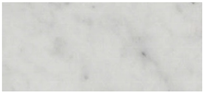

| Marmor Lunense | White pure sacaroid marble | Apuan Alps, Carrara, Italy |  |

| Marmor Sagarium | Carbonate breccia with white clasts and red matrix | Vezirhan, Turkey |  |

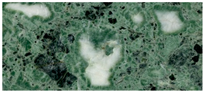

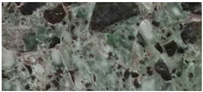

| Marmor Thessalicum | Green ophicalcite breccia | Chasabali, Greece |  |

| Rosso di Verona | Red limestone with ammonite fragments | Verona, Italy |  |

| Rosso Francia | Red limestone with sparry calcite veins | Caunes-Minervois, France |  |

| Verde Alpi | Green ophicalcite breccia | Western Alps area, Aosta, Italy |  |

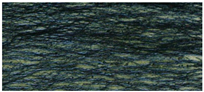

| Verde Ranocchia | Serpentinite | Wadi Umm Esh, Egypt |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acquafredda, P.; Micheletti, F.; Fioretti, G. Polychrome Marbles in Christian Churches: Examples from the Antependium of Baroque Altars in Apulia (Southern Italy). Heritage 2024, 7, 3120-3134. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7060147

Acquafredda P, Micheletti F, Fioretti G. Polychrome Marbles in Christian Churches: Examples from the Antependium of Baroque Altars in Apulia (Southern Italy). Heritage. 2024; 7(6):3120-3134. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7060147

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcquafredda, Pasquale, Francesca Micheletti, and Giovanna Fioretti. 2024. "Polychrome Marbles in Christian Churches: Examples from the Antependium of Baroque Altars in Apulia (Southern Italy)" Heritage 7, no. 6: 3120-3134. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7060147

APA StyleAcquafredda, P., Micheletti, F., & Fioretti, G. (2024). Polychrome Marbles in Christian Churches: Examples from the Antependium of Baroque Altars in Apulia (Southern Italy). Heritage, 7(6), 3120-3134. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7060147