Abstract

Landscapes have been shaped and reshaped by humans to meet the changing needs of shifting subsistence strategies and demographic patterns. In the Mediterranean region, a widespread subsistence strategy that has left a major imprint is pastoralism, often tied with transhumance. Pastoralism and the associated tensions between pastoralists and settled agriculturalists have political and legal dimensions which are sometimes overlooked in mainstream accounts of national “patrimony”. The rapid transformations of subsistence strategies witnessed in the twentieth century have changed pastoral landscapes in diverse ways. This paper focusses on the central Mediterranean archipelago of Malta to explore how the values and management of such landscapes require holistic assessment, taking into account the intangible practices and embedded legal rights and obligations that maintained these systems. While in Malta pastoralism has practically disappeared, its physical imprint persists in the form of a network of droveways, which was once a carefully regulated form of commons. Burgeoning demographic growth is erasing large tracts of the historic environment. Against this backdrop of contestation, this paper draws on interdisciplinary approaches to interrogate the shifting legal and historical narratives through which pastoral landscapes have been managed, in the process revealing how dominant epistemological and legal frameworks are also implicated in the erasure of these landscapes.

1. Introduction

The recognition of the importance of landscapes for our wellbeing has grown hand in hand with the unprecedented pressures and threats that they face today. Since the 1990s, the literature on the sustainable stewardship of landscapes has grown exponentially. A key theme underpinning this literature is the shift from a focus on sites and monuments, to a recognition of the need to safeguard their context in the wider landscape. A second paradigm shift has been the recognition of the inseparability of tangible and intangible aspects of cultural heritage resources [1]. A third paradigm shift has been the widespread recognition that landscapes are not simply the environments that we inhabit, but are embedded in human experience. The most influential articulation of this paradigm shift is the European Landscape Convention [2], which places human experience and quality of life at the heart of the rationale and purpose of landscape stewardship [3]. This succinct articulation of principle is in turn informed by a long tradition of cross-disciplinary research that has increasingly paid attention to the intricate social construction of space, place, and scale [4]. This rapid widening of the scope and range of approaches to the study of heritage and of landscapes has also highlighted the need for increasingly interdisciplinary approaches to cover the blind spots of different disciplines. All these considerations have informed the approach taken here.

This paper focuses on a threatened element of the cultural landscape of Malta (Figure 1). This consists of a network of droveways developed across the island to permit movement of flocks of goats and sheep for grazing (Figure 2). Pastoralism was an important pillar of the island’s economy well into the twentieth century. With the decline of pastoralism, many of these pastoral foraging routes have fallen into disuse. A significant proportion has been obliterated by modern buildings. Others are simply being erased as the land they occupy is taken up for other uses.

Figure 1.

Location of the Maltese archipelago in the central Mediterranean.

Figure 2.

Sheep being led down a steep droveway along the Bajda Ridge in northern Malta, 2005 (photograph N.C.V.).

The reasons for choosing to focus on these droveways are fourfold. First, they are a good example of a feature that does not fit the traditional definition of a monument or site. They are unassuming in appearance but represent a sustained and massive investment of effort and organization in their creation.

Second, the droveways are also a good example of a material record of the efforts of many generations of largely anonymous and marginalized members of society, who have for the most part been forgotten in historical narratives. The study of the droveways allows us some glimpse of these “people without history” [5].

Third, they are a good example of how systems of intangible rights and duties may be embedded in material remains. The droveways were carefully created to permit rights of way and use for grazing across the landscape, in symbiosis with crop cultivation. In spite of the disappearance of pastoralism, the access rights (and potential property rights) vested in these pastoral routes are still extremely relevant today. Malta has one of the highest population densities in the world, and the highest building density in Europe [6]. Space is extremely contested. The existence of a historic system of public rights of way, possibly associated with a forgotten form of “the commons”, is therefore a significant legacy with important implications for the enjoyment of public space today, which in turn has important consequences for wellbeing.

Fourth, the case of the droveways is an excellent example of the necessity of interdisciplinary approaches. Without a sound understanding of their historic evolution and of the legal rights that may be embedded within them, it is impossible to safeguard these rights, or even to comprehend the value and importance of preserving the droveways that embody them. In this respect, the droveways are therefore a sobering example of how inadequate knowledge may constitute a serious threat to cultural heritage.

2. Pastoral Routes in Mediterranean Landscapes

Archaeologists have long sought to study the impact that the development of animal husbandry has had on the landscape. For the Mediterranean region, interest has shifted from a Braudelian view that seeks continuities in the use of space over many generations of rural life, to traditions of landscape study that puts humans before physical geography, considering people’s perceptions of the constraints and opportunities offered by different ecological niches [7]. Pastoralism is seen as a complex form of economy, a practice that often requires dovetailing with a broader schedule of subsistence activities. The quantity of archaeological and documentary information that can be rallied towards an understanding of landscape history sets the Mediterranean apart from other regions of the world. Over the last fifty years, archaeologists have used multidisciplinary regional studies to investigate how the roles of people, climate, and topography have changed Mediterranean landscapes over time [8,9]. Ethnographic data have also provided useful insights into the apparently irrational ways in which decisions are sometimes made by the herder or the farmer, highlighting the different forms of environmental exploitation of ecologies that can offer comparably long spectra of productive choice. The kinds of conflicts that arise between transhumant herders and settled farmers, and the consequent need of the former to establish durable ties with powerful patrons who can mediate their interactions with the latter, is the central theme of John Campbell’s anthropological monograph on institutions and moral values in a Greek mountain community [10]. His study, which was based upon long-term ethnographic research among the Sarakatsani shepherds of continental Greece, is still regarded as a classic founding text of the anthropology of the Mediterranean.

Although it may be argued that pastoral activities entail few tools in comparison with agricultural ones, their material traces in the landscape can be abundant. In the history of some of the large European agro-pastoral societies, where groups of specialized herdsmen emerged, the migration of huge flocks over long distances left its marks on the land. Transhumance routes have been identified in various regions of Italy—Sardinian utturi [11] (p. 200), Sicilian trazzere [12], and Apulian tratturi [13]—but also in Spain (cañadas) [14], where droveways were often laid out according to clear legal provisions and edicts regulating the rights of access to common grazing grounds [15]. This tradition of seasonal droving of animals was recognized by UNESCO in 2023 and proclaimed as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity for several European countries, including Albania, Andorra, Croatia, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Romania, and Spain [16].

Movement of livestock has also been a common practice at local scales, not least on the smaller Mediterranean islands, where transhumance of small herds allowed people to move herbivores away from the cultivated fields and to exploit marginal areas for grazing (e.g., Antikythera) [17]. In such cases—and Malta would certainly not be an exception [18,19]—pastoralism and agriculture functioned in symbiosis rather than isolation. The ecological niche exploited for rough grazing often fell under the definition of what nineteenth-century British cartographers referred to as “waste” (or “wasteland”). This is a “weasel word”, as it has been called by Tarlow,

for the land in question was not unused as the word suggests; what the eighteenth and nineteenth-century reformers [in Britian] called “waste” was often productive, although non-agricultural, land [20] (pp. 45–46).

3. Pastoral Foraging Routes in Malta: The Ethnographic and Material Record

A ubiquitous feature of the Maltese landscape is the maze of dry-stone walled tracks and minor roads that can be found throughout the two main islands. The nature of the network has long been thought to be conditioned by geomorphology and the interplay of human settlement and agriculture over time [21] (p. 185). Such minor roads and connecting tracks are the human imprint on the land’s surface of a communication strategy intended for the passage of human and animal traffic before the advent of motor-driven transport.

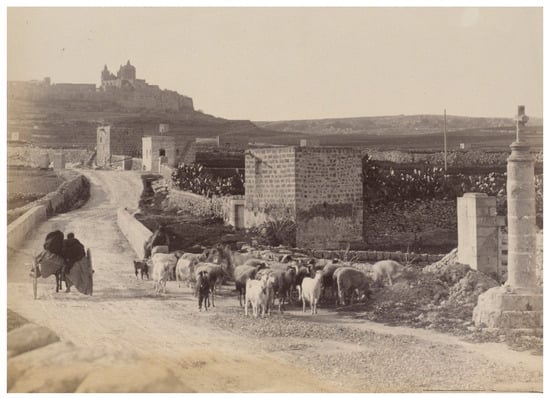

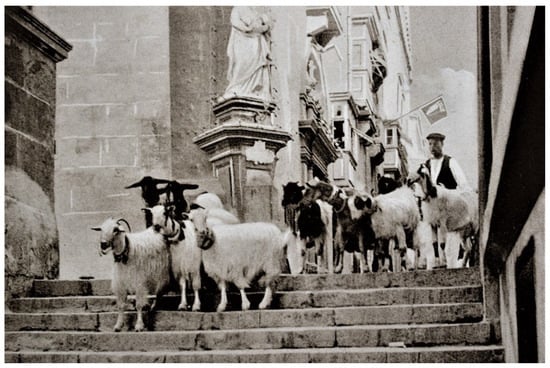

Photographs from last century reveal that such pathways also acted as droveways (Figure 3), allowing herders to move flocks of goats from pens to rough grazing or to bring them into the capital city and adjacent towns when it was still possible to sell milk doing the rounds of houses before the advent of pasteurization in 1938 [22] (Figure 4). This practice has been confirmed through interviews with a number of farmers who recalled specific strategies from the 1950s, by which herds of goats (and some sheep) were taken out to graze and to exercise in areas identified as wasteland—Maltese: xagħra and moxa—in the cartographic record amounting to just under 5000 acres or 6.3% of Malta’s total surface area at the time [19,23,24]. A sample survey of the feeding of goats and sheep conducted in 1956 showed that 80 per cent of herders relied on wasteland grazing to supply forage [24].

Figure 3.

Roadside grazing by a herd of goats below Malta’s old capital, Mdina, 1901 (reproduced by courtesy of Royal Collection Trust/© His Majesty King Charles III, 2024).

Figure 4.

Goats in a street in Malta’s capital city Valletta, photographed by Geo Fűrst in the early 1930s (reproduced by courtesy of Giovanni Bonello).

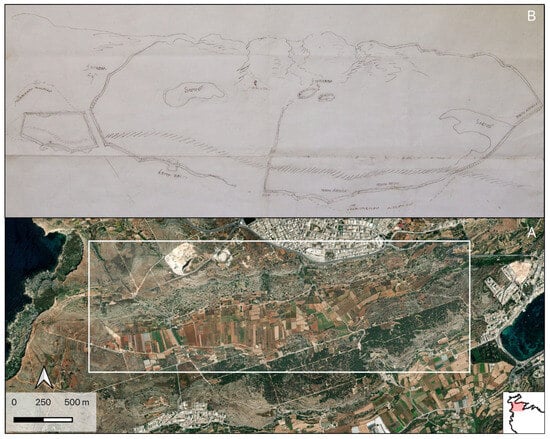

These droveways appear to have evolved more or less informally over the centuries in tandem with field systems. The earliest type of cartographic record that reveals fields enclosed with walls goes back to post-Medieval times, in the first quarter of the seventeenth century. It concerns access to contested lands in northern Malta consisting of arable fields spread across a valley basin at Miżieb ir-Riħ, bordered by rising ground used mainly for rough grazing (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(A) Modern orthophoto of northern Malta (2012, Planning Authority), compared to (B) plan of large field enclosures at Miżieb ir-Riħ in northern Malta, c. 1620s (reproduced by courtesy of Cathedral Archives, Mdina, Malta). Area of Plan B corresponds to white frame in A.

The lands effectively crossed the entire breadth of the island at this point. A reconstruction of the entire territory using cadastral maps of land belonging to the Church and to the Knights of the Order of St John that ruled Malta at the time, reveals that such tracts of enclosed land were often bordered by a “public road” (strada pubblica), which allowed human and animal traffic to move north and south. Some of these roads were wide enough to allow the actual pathway to be flanked by verges of common land, denoted by the cartographers as a “public space” (spazio pubblico).

The funnel-shaped entrances that characterize many of these walled tracks facilitated the droving of livestock (Figure 6), as has been argued for similar set-ups elsewhere [25] (p. 21). Their design stands in sharp contrast to a post-1850 field pattern of rectilinear fields, roads, and service tracks, which developed on non-Church land in the same area. This relates to a systematic attempt by the British colonial government to bring under cultivation marginal and poor terrain, inherited from the Knights of the Order of St John, by granting rectangular parcels of land demarcated by dry-stone rubble walls in emphyteusis to farmers [26].

Figure 6.

Droveway with funnel-shaped entrance along the Bajda Ridge in northern Malta (photograph N.C.V.).

4. Towards a Social History of Maltese Pastoralism

The interdisciplinary approach adopted here, starting from the ethnographic and material record, builds on the extensive work already carried out by historians on archival sources. A range of documentary sources may be drawn upon in the study of the Maltese landscape [27].

As noted by historian Charles Dalli [28] (p. 80), one of the earliest written references to grazing on Malta was recorded by the twelfth-century geographer al-Idrisi, who observed that the island had an abundance of grazing land. Dalli suggests this may indicate that land that had been enclosed for crop cultivation by the later Middle Ages was still unenclosed grazing land in the twelfth century.

From the mid-seventeenth century, an increase may be noted in the efforts to document land ownership through detailed land surveys in terriers or cabrei [2] (pp. 21–23).

Historical guide-books and descriptions of Malta allow us some further glimpses into the management and enclosure of grazing land. A mid-seventeenth-century account astutely notes how the different characteristics of different areas of Malta were suited to different productive activities, loosely translated here:

Animals pasture on the rocky ground, which produces grasses that are suitable to feed and fatten them. From the same place, thorns are gathered for burning in ovens when wood is lacking… on the plains, wheat, barley and other fodder is sown, while in the valleys there are gardens and orchards watered by copious springs [29] (p. 131).

A late eighteenth-century revised edition of the same work provides further insight into how grazing lands were being enclosed to help feed the growing population:

The fertility of this island has presently been increased because many public spaces (spazj pubblici) and lands that in the past had not been cultivated, have now been brought under cultivation. Food has become somewhat more expensive, because the population has increased a lot [30] (translated from p. 406).

The pioneering work of the medieval historian Godfrey Wettinger has documented the widespread designation of tracts of land as common land for grazing across late medieval and early modern Malta, such as the “spacium puplicum” recorded near the medieval hamlet of Ħal Millieri [31] (p. 51). Wettinger has also brought to light a number of specific references to contestations over grazing and access rights, stretching at least as far back as the Late Middle Ages. From the early fifteenth century onwards, when surviving written records become more abundant, numerous instances are recorded of popular protests against the enclosure of land that had previously been available for pasture, which in some cases secured the revocation of such grants of public land [32] (p. 269); [33] (pp. 31–32).

Miżieb ir-Riħ features amongst cases concerning such grievances. In 1458, complaints were made against a powerful landlord, Antoniu Desguanes, from the capital, Mdina, who was accused of capturing extensive portions of common land at Miżieb ir-Riħ by appropriation and enclosure to the detriment of the community, with the King’s permission [33] (p. 33); [34] (pp. 42–43). Herders complained that these lands ran across the route to barren lands that had been the property of all the people of Malta for as far back as anyone could remember, and that these lands extending towards the district of Mellieħa provided rough grazing for animals and were a useful source of brushwood for fuel. People were afraid that if animals strayed into the fields owned by Desguanes they would be held liable for damages by the baiulo—the official responsible for imposing fines commensurate with the damage inflicted on crops. It was agreed by the Council of Mdina and the jurats that Desguanes would be able to keep a part of the land, but that he would need to enclose the area with a wall to stop animals from straying there. He was also required to not block public passageways and to not restrict access to the springs in the area. Although pictorial representations of this area do not exist from this period, it is probable that one of the roads shown on the early-seventeenth-century cadastral map referred to earlier (Figure 5) is one of the droveways that allowed passage through the valley basin, towards a spring (fontana) and the commons beyond.

Wettinger has noted several other instances, throughout the fifteenth century and across Malta and Gozo, of individuals obtaining grants of common “waste” land, which until then had been available for pasture, in order to turn it into arable fields. The cultivation of cotton, traditionally the principal cash crop of the Maltese islands, often motivated such grants [33] (pp. 10–11).

The herders’ objections that the King was permitting the expropriation of common lands acquire deeper significance when considered in the light of the medieval legal hybridity which characterized Maltese law in this period [35,36]. At the time, local customary law was considered to be an important source of law throughout Europe [36] (p. 377), alongside the Ius Comune (incorporating the Roman Law together with Canon law and doctrinal commentary) and feudal laws [37] (pp. 32–33, 37); [35] (pp. 178–180). In the herders’ complaints, communally owned property is presented as based upon ancient Maltese customs, which provide a normative buffer against land appropriation through feudal hierarchies legitimized by Sicilian feudal law. A retrospective reading that assumes the existence of a unitary legal logic governing this conflict misses the point that this is not only about a power struggle between herders and powerful barons. This is also a clash between distinct and incommensurable normative systems, corresponding to two different modes of production and the associated social structures; and this at a time when plural and incompatible normative systems were more the rule than the exception. As Brian Tamanaha observes:

The mid-to-late medieval period was characterised by a remarkable jumble of different sorts of law and institutions, occupying the same space, sometimes conflicting, sometimes complementary, and typically lacking any overarching hierarchy or organisation [38] (p. 377).

During the late medieval period, the principal representative and administrative body on the island of Malta was the Council or Università, based in Mdina [39]. The Università of Mdina played a critical mediating role, functioning as a node of articulation between diverging normative systems. In a scholarly study of this Council as an example of a medieval communal organization, Dalli notes that while on the one hand this Council “channeled and regulated political relationships in the public sphere and derived its legitimacy as the representative and executive body from its official recognition by the Crown” [40] (p. 1), on the other hand, in 1410 the Council was still invoking “certain ancient unwritten customs and conventions”, quoted by Dalli [40] (p. 8). Its intervention in the 1458 Miżieb ir-Riħ case shows how this institution was considered to possess the authority to regulate how Baron Desguanes could exercise the powers of land appropriation that he had been granted by royal permission. Dalli observes how, nearly a decade earlier, the Council had already intervened in an attempt to prevent Baron Desguanes from committing very similar encroachments:

In 1449, following serious accusations from the town council that Desguanes, as mayor, was encroaching on public lands administered by it, like Mizieb ir-Rih, it was demanded that a Sicilian, with no Maltese connections, be appointed captain. The Crown agreed on condition that the town-council redeemed that office [40] (p. 9).

Its regulatory function was thus part and parcel of the role this Council played in administering what the herders had described as “common lands which had belonged to all the people from time immemorial”. This expression is echoed in the claims made by the Council itself in the later Middle Ages that “it had enjoyed rights over common lands for the past three centuries” [28] (p. 124). In letters sent to the Crown in 1466, this Council described itself as “a mother who must procure a peaceful life for her people and children” [40] (p. 9). Even the fact that this Council was known as “the Università” reflects its role as administrator of commonly owned land, whether this was understood as a reference to the “totality of the people” (a universitas personarum in Roman law [41], or to “a totality of objects treated in one or more respects as a whole in law” (a universitas rerum in Roman law) [42]. To say that land belonged to the Università may simply have been another way of saying that the land was owned in common by the people of Malta and administered by the Mdina Council. This did not necessarily imply that such land was owned by the Mdina Council.

Bartolomeo dal Pozzo, a seventeenth-century chronicler, records similar contestations during the early years of the rule of the Knights of the Order of Saint John in Malta (1530–1798). The Knights and their Grand Master were accused of infringing the rights of the Maltese population. Dal Pozzo records how, following the death of Grand Master Verdala (1582–1595), a Chapter General of the Council of the Order was convened, which ordered, among other things, that

… all the public spaces, or lands, belonging to the commons of the Island of Malta, which past Grand Masters, and particularly by Cardinal Verdala had granted to private individuals; upon which public protests had been made; must be returned once again to the commons [43] (translated from p. 366), [32] (p. 269).

Similar tensions are again recorded in the early seventeenth century, in an anonymous account preserved in two manuscript copies in different archives in Malta, and which Wettinger [32] (p. 257) has dated to between 1633 and 1636 and attributed to Don Filippo Borgia, rector of the parish of the village of Birkirkara and champion of the local population against abuses of their traditional rights. According to the author of this account, Grand Master de Paule (1623–1636) again made encroachments on public spaces, notwithstanding the resolutions that had been made following Verdala’s death [32] (pp. 269, 277–278).

The terminology used to describe the land being contested, and how the contestation changes over time, deserves particular attention. As astutely observed by Wettinger, in the fifteenth century it was not only the wealthy and powerful that received grants to enclose land, but also individuals from across all classes of society [33] (p. 10). In the seventeenth-century account attributed to Don Filippo Borgia, the enclosure of grazing land is presented as a struggle between the poor and the powerful. Enclosed lands are described as “spatii publici levati al pover” (public spaces taken from the poor) [32] (p. 277). The chronicler Dal Pozzo, as noted above, is even more explicit, referring to “spatii publici o sia terreni del commune dell’Isola di Malta… di nuovo ritornar dovessero in commune” (public spaces, that is lands belonging to the commons of the Island of Malta… must be returned to the commons) [43] (p. 366).

Wettinger observes, in a paragraph that deserves to be quoted in full:

One sore point was the common land frequently allotted in severalty to individuals: such grants removed the land from the use of the poor who depended more than anyone else on their grazing rights and the right to gather fire-wood or thistles from such places. After Verdala’s death these lands were returned to public ownership not only by the will of the Council of the Order but also by decree of Pope Clement. Don Filippo claimed that he had persuaded the Grand Master not to make similar grants without the consent of the Pope, but had to overcome the influence of ‘the good ministers who stood around him and who are more often the cause that Princes do not do what they should’, so that at his next meeting the Grand Master told him: You have informed me that I cannot do it without the consent of the Pope; and I tell you that my counsellors say that the Pope does not come into the matter. I want to do it because I am master [32] (p. 269).

This seventeenth-century clash between Don Filippo Borgia and Grand Master de Paule echoes the fifteenth-century conflicts between herders and barons. Significant discontinuities with these earlier conflicts can also be observed, signaling a movement towards an early modern legality. The Grand Master’s words reveal an aspiration towards complete sovereign control of all the public lands in Malta. The Università (qua Mdina Council) is no longer mentioned as having any administrative role in regard to such lands, and the customary rights of common land ownership of the people of Malta are not permitted to restrain the exercise by the Grand Masters of their power to appropriate and dispose of these lands.

In his attempt to erase Maltese customary rights and to side-line both the Pope and the Università, Grand Master de Paule’s actions conform to those of other early modern princes. As Tamanaha [38] observes, such princes sought to eliminate medieval legal hybridity in their quest for exclusive sovereign control over “their” increasingly centralized legal systems. In this process of constructing a unitary legality, customary law was “taken over by legal professionals” and “lost its primary ties with its social base” [38] (p. 380). Moreover: “It was also essential for sovereigns to establish their autonomy from the Church” [38] (p. 379).

The success of this strategy is revealed also by the absence of any reference to the Università in Don Filippo’s reported defense of these lands. He prefers instead to invoke the patronage of the hierarchically organized Catholic Church, represented by the Papacy, as the protector of the rights of the poor to access and utilize public lands. By the seventeenth century, Maltese pastoralists found that they could no longer rely upon the Università to mediate and resist the state appropriation of public lands. Indeed, since 1530 the Università had been progressively emasculated as a result of the Order’s constant policy to “ensure that the effective Government of Malta should be located in Valletta and that Imdina should host a local Government deprived of all powers that were not absolutely residual” [44] (p. 143); see also [45].

Since the Grand Masters themselves headed a Catholic Religious Order, the universal Catholic Church could not be marginalized as easily as the Maltese Università had been. This explains why the Catholic Church was to replace the Università as a source of political patronage to Maltese herders and villagers. Wettinger notes that Dun Filippo Borgia’s account reflects this political transition, which would lead the Church to become the chief mediator between the rural Maltese and the governors of Malta until the end of the period of the Knights’ rule and throughout that of British rule:

It marks the complete eclipse, much to the satisfaction of Don Filippo and, no doubt, of Don Francesco, another lawyer priest, of the medieval political set-up, with the fading away of the local ‘nobility’ and the rise of the clergy to a status of influence… In the past, clergymen had been for hundreds of years all-powerful as churchmen. From now onwards for three centuries they would be extremely influential as politicians [32] (p. 270).

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, this alliance between the rural Maltese and the Church came increasingly to the fore. As the Order’s prestige and relevance began to decline, the rural Maltese, often led by priests, started to protest and agitate for their rights. Chief among these was their right to access and use their common lands and droveways, which were being enclosed and appropriated by the Order. Thus, the imposition of new restrictions on rabbit hunting on his estates and the consequent eviction of herders from grazing land by Grand Master Ximenes seems to have sparked the so-called “Priests’ Revolt” of 1775 [46], and the resentment by the rural Maltese at the loss of their communal rights seems also to explain their reluctance to fight for the Order against the French invasion of Malta in 1798 [47] (p. 26). Finally, the defense of their communally owned property not only explains why the rural Maltese were so ready to rebel against the French Republican army, but it also explains how they managed to fight them so successfully. Stephen Spiteri observes:

The (Maltese) inhabitants knew that they had neither the men nor the resources to lay siege to the formidable and well-armed harbour fortifications and so all their efforts were aimed at making a French excursion out of the harbour enclave as difficult as possible. Here, they ingeniously exploited the nature of the rural landscape surrounding the fortifications which, divided into innumerable stone-walled fields, provided a readymade system of entrenchments. All that the inhabitants had to do was to link the field walls together, plugging in country lanes, roads, and valleys, and in so doing create an extensive and continuous form of circumvallation. They then stiffened this with a number of camps, batteries, and sentry-posts placed at strategic intervals [48] (p. 13).

During the following century and a half of British colonial rule (1814–1964), further encroachment and enclosure took place on land that had formerly been available for grazing. Substantial tracts of the shoreline, as well as inland areas, were taken over for military purposes as the island was turned into Britain’s kingpin in the defense of the “Mediterranean Corridor” to India, particularly after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Meanwhile the growing population also led to mounting pressure to increase agricultural productivity. The looming threat of starvation during the Napoleonic wars left a deep impression on the island’s administration. The paradigm of agricultural improvement, widely embraced in Britain [20], was also brought to bear in its colonial possessions, and Malta was no exception. A statement of income of the government of Malta for the fiscal year 1835–1836 refers to the “sale of waste ground” for 24 pounds sterling [49], suggesting that grazing land was being sold to private individuals.

During the period of British colonial administration, the concept of a native commons, as opposed to property of the Crown, appears to have been obfuscated and forgotten. The designation of pasture as “wasteland” not only underplayed the important economic role played by this land, but also helped obliterate the history of public rights that had been so carefully defended in the preceding centuries. The assumption that grazing grounds were government property, and in the gift of the colonial government to lease or sell, does not appear to have been questioned.

This shift in the way common grazing land was perceived may be better understood in the context of the wider paradigms that informed and justified British colonial projects and worldviews during the nineteenth century. In his perceptive historical anthropology of colonialism in the area of South Africa occupied by the pastoralist Tswana people, John Comaroff [50] explored the strategies utilized by colonial administrators to facilitate and legitimize their appropriation of Tswana lands. He observes that these strategies involved the strategic deployment and management of the opposition between Western notions of exclusive individual ownership rights—which aligned with settled farming practices—and traditional Tswana communal land management practices—which reflected their pastoralist economy. With specific reference to the Bechuanaland Land Commission, Comaroff argues that this Commission “negated the collective capacity of a community and its leaders to remake their own world by due process” [50] (p. 230).

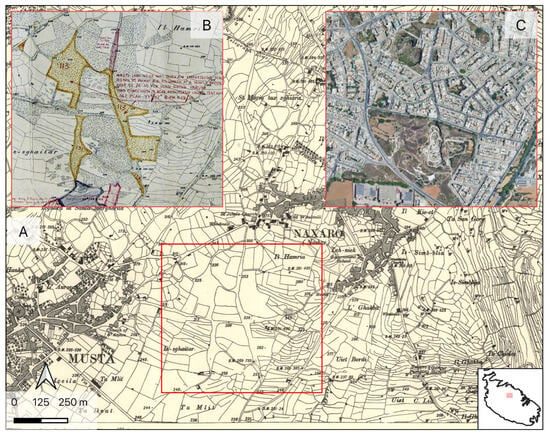

Although the context of British Malta was very different, certain patterns and consequences stemming from similar colonial tactics may nevertheless be recognized. Maltese grazing land was subjected to a direct frontal assault early on in the period of British rule, when the first British Governor of Malta, Sir Thomas Maitland, abolished the Università in 1818 [51]. As noted above, the loss of the institution that traditionally safeguarded common rights to grazing land through communal governance was followed by the implementation of government policies that set out to enclose grazing land, convert it into agricultural land, and alienate it. A critical role in this process of privatization was played by cadastral surveys, through which the colonial government formalized its hold on such land by mapping it and redefining it as government-owned wasteland (Figure 7). As the colonial government developed ever more sophisticated tools for legally categorizing and appropriating these grazing lands and pathways, the devolution of these lands to the colonial government was to be almost unchallenged.

Figure 7.

(A): Early twentieth-century survey sheet showing location of a section of pastoral route network between villages of Mosta and Naxxar. Area framed in red corresponds to insets (B) and (C). (B): Annotated survey sheet showing the same network, highlighted in yellow and labelled as “Waste Land”. Mid-twentieth century (NAM PWD—Project House, Government Property Survey Sheets, No. 50). (C): The same area in 2018, drastically altered by quarrying and building activity (SintegraM orthophotos (2018), Developing Spatial Integration for the Maltese Islands, Planning Authority).

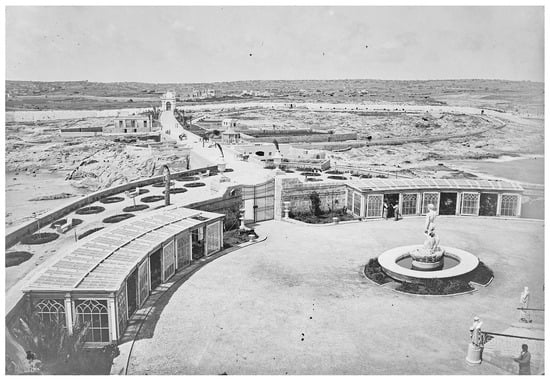

A late nineteenth-century court case can provide us with a glimpse into the legal reasoning through which the appropriation of Malta communal lands was made possible under British rule. The case of Emmanuele Luigi Galizia v. Emmanuele Scicluna made possible the privatization of part of the Maltese coastline in the area now known as the Dragonara Casino zone in Saint Julian’s [52]. This case arose out of the aspirations of Emmanuele Scicluna, a leading Maltese banker, who had acquired the landholdings of the Spinola Foundation, to create a feudal domain of his own. He therefore built a palace on this land and sought to enclose the coastal promontory on which this palace is located—including substantial tracts of grazing land—with a wall on the landward side. This wall effectively prevented the government and the public from accessing either this promontory or the coastline surrounding it. The Superintendent of Public Works, Emmanuele Luigi Galizia, filed a possessory action to prevent the building of the wall and to allow unimpeded access by the government to the military fortifications on this land and by the public to the coast. On 30 April 1886, the Court of Appeal delivered its judgment. In this case the court held that government’s property rights only extended to the footprint of the land upon which its military fortifications had been constructed. The court concluded that, notwithstanding that the remainder of the land belonged to Scicluna and he had therefore the right to enclose it with a wall, he still had no right to prevent access by the public to the coast or by the government to the entrenchment. Consequently, the court held that Scicluna had to leave the arched gateway he had constructed in the wall of his estate permanently open, allowing the government to have continual access to its military property and allowing the fishermen and “salt-gatherers” continual access to the sea and the saltpans.

What is striking about this judgment is the complete absence of any reference to the grazing land contained within Scicluna’s enclosed promontory (Figure 8). This in turn facilitates a judicial overlooking of the possibility that the government’s claim to possess public land within this enclosure could have a different basis than its ownership of the military entrenchment within it and its role as guardian of the Maltese public’s rights to access the coast. In the process—and even though it would have been in its interest to do so—the colonial government had completely abandoned any claim to possess the grazing lands used by the Maltese herders and to administer them in their name. It is only the coastal land, and not the grazing land, which, as a res extra commercium, the government continues to administer in the interests of the public, and the only right granted to the members of the public over the grazing land is to access the coast by traversing it. This case clearly shows how, by the end of the nineteenth century, Maltese pastoralists’ communal property rights had dwindled into mere rights of access.

Figure 8.

Photograph by Richard Ellis showing the access gate (top left) in the wall that enclosed the Dragonara Palace and the surrounding garigue grazing land. Late 19th century (reproduced by courtesy of the Richard Ellis Archive—Malta. M52-02).

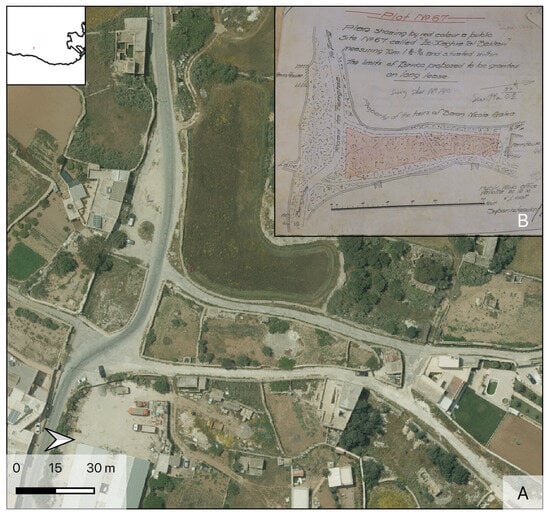

The documentary evidence for the twentieth century is particularly detailed, making it possible to date and trace the more recent history of enclosure of former grazing land even more closely than in earlier periods. During the early twentieth century, particularly during and following the First World War, areas of former “wasteland” were systematically leased out or sold for agricultural purposes and for building. A series of plans preserved in Roll 73A at the Records and Archives Section of the Public Works Department provides detailed insight into how this policy was implemented. Unenclosed land was surveyed, and new enclosures defined and plotted onto these areas. When carving out a new enclosure, care was taken not to obstruct existing roads, and to leave narrow corridors that still allowed movement across the landscape, albeit through much more restricted spaces (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

(A): Enclosed field formed by taking over part of a droveway at Tal-Bakkari, l.o. Żurrieq (SintegraM orthophotos (2018), Developing Spatial Integration for the Maltese Islands, Planning Authority). (B): Plan dated 20 December 1916 showing the demarcation of the same area in red, when it was designated for enclosure and lease (Roll 73A, 7A. Records and Archives Section within the Public Works Department).

The early 1930s were marked by a flurry of debate and legislation intended to safeguard and improve the productivity of the islands’ scarce resources. The Government’s efforts in this period to increase the productivity of “wasteland” were not driven purely by economic viability, but also by political and ideological considerations. In a debate in the Senate on 26 October 1932, the Leader of the Opposition, Gerald Strickland, pointed out that:

… Ministers should be careful with public money. Money and reports were lavished upon dynamite to break up the rocky ground. The dynamite cost much more than any produce of crops raised on those lands [53] (p. 50).

During a debate in the Legislative Assembly on 22 November 1932, the Minister of Agriculture stated that government was considering legal provisions to preserve the soil from areas that were being taken up by building, and rather than let it get buried under building, to use it to improve rocky terrain to make it viable for crop cultivation [54] (p. 385). Progress with enacting these measures appears to have been slow.

The outbreak of the Abyssinia Crisis in early December 1934 renewed the prospect of war, and may have given a fresh impetus to the need to safeguard agricultural productivity and food security in Malta. A series of ordnances were issued barely a month later, in January 1935. Ordnance I was intended “To facilitate the preparation of Agricultural Statistics”. Ordnance II, published the same day, was “To provide for the preservation of fertile soil” [55].

Ordnance II of 1935 was complemented by a “List of lands on which fertile soil may be deposited…”, published on 26 January 1935 [56] (p. 80). Over 50 “wasteland” sites across the main island of Malta are numbered and listed, with measures on how to facilitate the deposition of soil that had been removed from building sites across the island.

An interesting exception to the leasing and selling of former grazing land for other purposes appears to have been made for areas that were considered to be archaeologically significant. The ordnance of 1935 came a decade after the enactment of the Antiquities Protection Act, which gave the state extensive powers and responsibilities to identify and protect archaeological sites [57]. As a result, areas of unenclosed “wasteland” in public ownership that were considered to be of archaeological significance, and which were included in the list of protected ancient monuments published in 1927 [58], were not included in the 1935 list of sites that could be covered in soil.

Since the second half of the twentieth century, successive building booms have continued to take up more land area for residential, commercial, and infrastructural building activity, making Malta the most built-up country in the European Union in 2018 [6]. This intensification in built-up areas has also had an impact on the former pastoral landscape. The redesignation of pastoral routes for building, which was already being practiced in the first half of the twentieth century, continued apace. Meanwhile, the feeding regimes used by sheep farmers were also changing. By 2021, the most widespread method had become the use of dried hay as fodder [59] (p. 102).

Transformation of co-owned rights into mere rights of access found its latest expression in the planning policies of Malta’s Planning Authority, which seek to safeguard traditional and historical country pathways and their character [60] (Policy 1.2I). The same guidance document states that the term “country pathway” must be interpreted in a very broad sense to include, inter alia, rights of way, defined as informal tracks, normally unsurfaced, passing through arable fields and providing access to farmers or land managers having no direct access to their land from country roads or lanes, and informal pathways, which are described as those normally established on natural sites and characterized by compacted ground as a result of continuous trampling and erosion.

5. Transformation, Contestation, and Recovery: Five Examples

The extensive transformations of the Maltese landscape outlined above have resulted in the partial or total obliteration of a high proportion of the network of pastoral land and foraging routes that once extended across the archipelago. This transformation has been driven by different factors, which will be illustrated by the following examples. These factors may be observed alone or in concert. The following examples are intended only to illustrate their impact, and not as a comprehensive inventory of all the possible scenarios.

5.1. Absorption into the Road Network

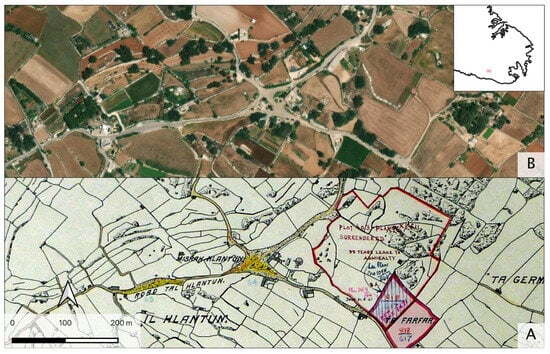

Pastoral routes developed organically as an integral part of the road network that allowed movement across the island. As noted earlier, public roads were often flanked by a wide verge, allowing the same corridor to serve for the passage of flocks of grazing sheep and goats, as well as other traffic. In many cases, these thoroughfares have been retained and absorbed in the present-day road network. These typically have metalled roads to accommodate modern traffic, but often preserve the unmetalled verges, in whole or in part. In plan, the distinctive planimetry of the network is often preserved largely intact, as are many of the dry-stone walls that demarcate their boundaries. Examples of this process that are especially recognizable include several of the abandoned medieval settlements originally identified and studied by Blouet [61] and Wettinger [62]. Examples include Ħal Millieri, Ħax-Xluq, Ħal Mann, and Ħlantun (Figure 10). All these examples preserve a distinctive node where different country lanes converge in a wide, open space [19]. Evidence of their past use for pastoral activity is preserved in their planimetry, as well as several of their toponyms. As noted earlier, their planimetry is characterized by the distinctive funnel-shaped junctions that connect the wider open spaces with the more linear corridors. The toponymastic evidence preserves several references to a “misraħ”, a term for which the most widely accepted translation is an open space for grazing [63]. In some instances, the toponyms associated with these nodes make even more explicit references to grazing, as at San Niklaw tal-Merħliet, literally “Saint Nicholas of the Flocks”.

Figure 10.

(A): Detail of annotated survey sheet showing droveway network, highlighted in yellow, at Ħlantun, l.o. Żurrieq. Note the toponym “Misraħ Ħlantun”. Mid-twentieth century (NAM PWD—Project House, Government Property Survey Sheets, No. 140). (B): The same network in 2018 (SintegraM orthophotos (2018), Developing Spatial Integration for the Maltese Islands, Planning Authority).

5.2. Enclosure for Crop Cultivation

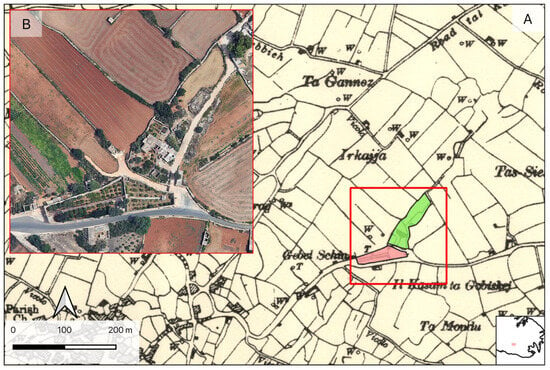

The historical record reviewed earlier documents numerous instances of enclosure of common grazing grounds to create fields for crop cultivation, ranging in date across half a millennium, from when surviving written records become more abundant in the fifteenth century, well into the twentieth. In some instances, a stratification of successive enclosures may be made out, encroaching progressively further onto former grazing land, using the evidence of the morphology of the fields themselves, as well as the cartographic and archival record (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

(A): Detail of early twentieth-century survey sheet showing successive enclosures of parts of a former grazing land near Safi. Area highlighted in red shows the extent of a garden created by the government in 1804. Area highlighted in green shows another enclosed part of the former grazing ground, probably enclosed at an earlier date. (B): The same area in 2018 (SintegraM orthophotos (2018), Developing Spatial Integration for the Maltese Islands, Planning Authority).

5.3. Urbanisation

The exceptionally high density of building on the Maltese archipelago, which, as already noted, has the highest proportion of artificial ground cover in Europe, has also accounted for the erasure or absorption of a large area of former grazing grounds. The replacement of grazing grounds with artificially built surfaces may take several forms. The buildings of airfields alone necessitated the erasure of several square kilometers of the pre-existing cultural landscape. Four airfields were built on the island of Malta during the first half of the twentieth century. The largest of these, which still functions as the country’s airport today, alone accounts for over 1% of the land surface area of the entire archipelago. Industrial activity and residential building have also taken up large areas of the former agricultural landscape. In some cases, new road layouts have erased all visible traces of past configurations of land management and use. In other cases, the imprint of these past uses, including grazing, still persists in a form that may, to varying extents, be read from the material and the archival record.

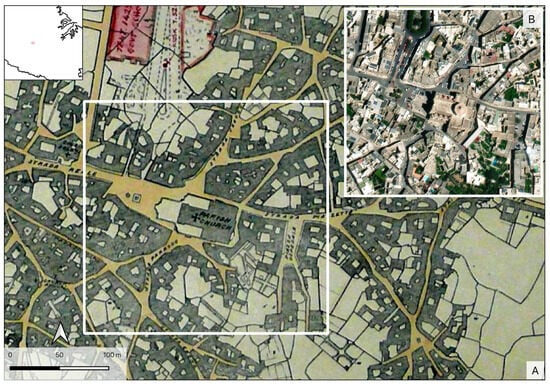

A widely attested, but to date little-studied, phenomenon is the influence of pastoral routes and the surrounding field enclosures on the urban form of settlements that developed in the early modern period. Historic village cores that took shape between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries are largely the result of successive building interventions by single individuals, which more often than not were added organically, without a master plan. As a result, these historic urban cores often respected and preserved the layout of existing road networks and property boundaries, and of course the boundary between private and public property. A direct corollary is that these urban cores may today still preserve a fossil imprint of the delineation of long-lost pastoral routes. This may help explain the distinctive street plan of early modern village cores, which is characterized by funnel-shaped open spaces where streets converge (Figure 12); these are morphologically very similar to the patterns observed in pastoral routes preserved in a rural context.

Figure 12.

(A): Detail from annotated survey sheet showing street layout in the village core of Ħaż-Żebbuġ. Early to mid-twentieth century (NAM PWD—Project House, Government Property Survey Sheets, No. 89). (B): The area framed in white in (A) as it appeared in 2018 (SintegraM orthophotos (2018), Developing Spatial Integration for the Maltese Islands, Planning Authority).

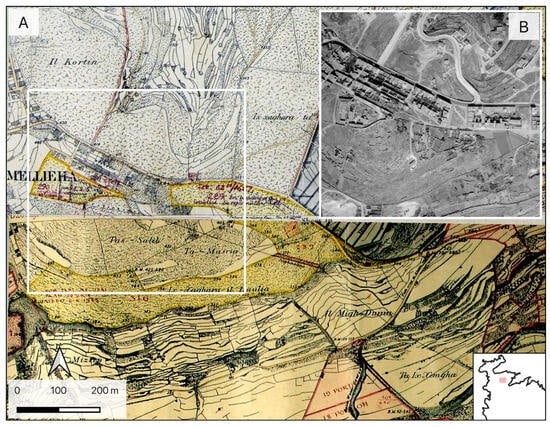

The urbanization of former grazing lands took a very different form in the British colonial period, which in some ways was an inversion of the early modern pattern of urbanization along and around pastoral routes. By the early twentieth century, former pastoral routes had been largely appropriated by the colonial government, and in some cases were being allocated for building within their footprint. In the village of Mellieħa, for instance, which grew considerably in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, a former pastoral route was one of the first areas to be given over for building, long before urban expansion spilled over into the enclosed lands on either side of it (Figure 13). A short distance to the south of Miżieb ir-Riħ, the present-day hamlet of Manikata provides another good example. During the 1930s, a corridor that until then was used for grazing, was divided into plots for building. The area once occupied by former pastoral routes accounts for a significant proportion of the built-up area of Manikata today (Figure 14).

Figure 13.

(A): Detail of annotated survey sheet showing the droveway network, partly shaded in darker yellow, at Mellieħa. Early to mid-twentieth century (NAM PWD—Project House, Government Property Survey Sheets, Nos. 13, 18). (B): The same area in 1967. Note the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century buildings visible within the droveway on the survey sheet, and further increases in built-up area within the droveway by 1967 (National Collection of Aerial Photography, Historic Environment Scotland NCAP_SAL_HSL_MALTA_67_0004_0785).

Figure 14.

(A): Twentieth-century building development in Manikata hamlet. (SintegraM orthophotos (2018), Developing Spatial Integration for the Maltese Islands, Planning Authority). (B): Plan dated 15.11.1922 showing parceling of the former pastoral route in the same area into building plots (Roll 73A, 13A. Records and Archives Section within the Public Works Department).

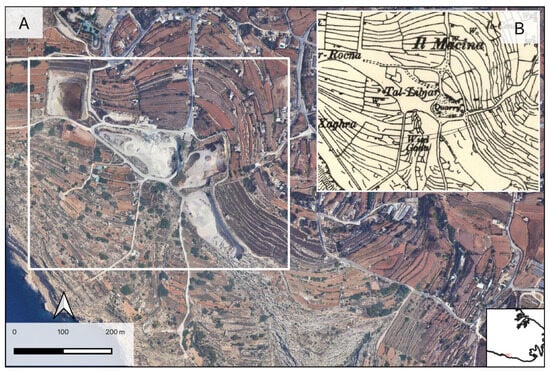

5.4. Destruction by Quarrying

The characterization of grazing land as “wasteland” rendered it vulnerable to another, even more destructive, reassignment to a different purpose. Grazing land on coralline limestone outcrops, where enclosure and agricultural improvement for crop cultivation may be particularly challenging, was in several cases leased or sold by the state for the quarrying of hardstone gravel (Figure 15). Lower Coralline Limestone outcrops were particularly prized for this purpose, and, as a result, during the course of the twentieth century they were largely destroyed across the archipelago, together with any trace of earlier use.

Figure 15.

(A): Extensive quarrying within the footprint of a former droveway near Nigret, limits of Żurrieq (SintegraM orthophotos (2018), Developing Spatial Integration for the Maltese Islands, Planning Authority). (B): Detail of early twentieth-century survey sheet showing the same droveway. Note the toponym ‘Tal-Ibjar’ ([the place] of the [rainwater] cisterns).

5.5. Preservation and Scheduling

Against this background of drastic adaptation, transformation, and erasure, the preservation of pastoral foraging routes in a relatively unaltered state is the exception rather than the rule. There are, however, several such notable exceptions. In a number of cases, they fall within areas that have been preserved and scheduled in national registers of protected assets, usually because of their recognition as Areas of Ecological Importance or Areas of Archaeological Importance. One example is the area around the former troglodyte settlement of Għar il-Kbir, and the cart ruts in the immediate vicinity, near the southwest coast of Malta. Both these sites were included in the list of protected ancient monuments published soon after the enactment of the 1925 Antiquities Protection Act [58] (p. 25). In 1998, an extensive area of karstland around these features was scheduled as an Area of Archaeological Importance, effectively also protecting the traces of pastoral foraging routes that fall within the same area. Another area of karstland at Tal-Wej was scheduled in 2011 with recognition of both an Area of Archaeological Importance and an Area of Ecological Importance, while also noting that it represented a significant multi-period cultural landscape. Although to date pastoral foraging routes have not been expressly scheduled in their own right, in such instances they nevertheless enjoy holistic protection as part of the cultural landscape.

6. Discussion

The fragmentary nature of the history reviewed earlier is not accidental. The history of the droveways as a form of commons is not simply a history from the margins, it is a marginalized history. The recurrent cases of appropriation of these commons, recorded at least since the fifteenth century, rested on their obliteration in memory as well as in the material landscape. The progressive obliteration of the grazing grounds and droveways that has been traced here is another example of the much more widely attested phenomenon of enclosure of the commons across Europe and beyond [64,65]. The erosion and loss of landscape commons has been analyzed and described in Rotherham’s seminal work as a form of cultural severance, in which it is not only the physical landscape that is being modified, but also the nature of human engagement with that landscape [64]. As argued by Olwig, the enclosure of commons in the landscape often came hand in hand with another form of “enclosure”, this time of “Cultural Commons”, which severed the traditional relationships between people and place [65] (p. 39). One of the consequences has been that over the course of the past century, the rise of globalism has fundamentally altered perceptions of land and place, which has become increasingly commoditized and turned into property [65] (p. 43).

A sound understanding of the long history of contestation between competing interests in the landscape is a prerequisite for the management of the values and significance of the same landscape today. In such settings, heritage practitioners in the stewardship of historic landscapes are not only required to be guided by interdisciplinary knowledge, but they are also required to engage with contemporary ethical concerns, and to contribute to equity and wellbeing in the society they serve, in the spirit of the European Landscape Convention [2].

The interdisciplinary exploration that took place during the writing of this paper went through several iterations, which entailed many conversations. Each iteration between the evidence and the discussion of its implications led to fresh realizations. Ethnographic observation has provided a sound point of departure to understand the key characteristics of pastoral foraging routes and their purpose. Read from the perspective of law and legal anthropology, the material and archival evidence spoke eloquently of a struggle between very different normative systems, as new power structures tried to overwrite existing ones. In turn, the legal insights into the evolution of attitudes to private and common property have allowed a more informed reading of the evolution of the material form of pastoral landscapes, while the archival evidence has shed new light on their transformation in the British colonial period.

This hybrid approach has also opened up fresh avenues for further investigation. One such avenue has been the recognition that the organic development of urban centers in the countryside during the early modern period may preserve an imprint of pastoral foraging routes and the surrounding field systems in their street layout. This is significant for at least two reasons. The first is archaeological, in that it opens another avenue of investigation into the material record of lost landscapes. The second is architectural, in that it allows new insights into the development of the urban form that give early modern villages such a distinctive planimetry, as well as adding a new and previously undiscussed layer of value and significance to these urban forms.

The preliminary study undertaken here has further demonstrated that pastoral routes in the Maltese context, which before the writing of this paper had barely received a mention in the discourse about heritage preservation, are in fact a crucial component of the Maltese cultural landscape. They not only played a central role in the subsistence strategies of past inhabitants, but also represented a remarkable framework of rights and obligations founded on a concept of commons. The separation between the more tangible, material aspects of pastoral routes, and their more intangible legal and conceptual aspects, is a demonstrably artificial and unhelpful divide. Shifting subsistence strategies and structures of power and authority have resulted in a long history of contestation and redeployment of the material landscape where pastoralism was practiced.

The successive transformations of the Maltese landscape that have been outlined, as commons first became “wastelands”, and then private land, fit squarely into the wider picture of cultural severance described by Rotherham [64]. In the process, the significance of pastoral routes has also morphed considerably, presenting new challenges and opportunities in their management and use, as new values come to the fore. On the global scene, the rediscovery and reworking of traditional commons is increasingly becoming an important ingredient in innovative approaches to the sustainable management of cultural landscapes, across countries ranging from the United Kingdom [66] to Japan [67]. This potential for reworking and reinvention of the commons for the future stewardship of the landscape also holds true for Malta. Even as the practice of pastoralism has receded, the pastoral routes hold the prospect of being invested with fresh significance. Today, the burgeoning overbuilding of the archipelago is increasingly acknowledged to be eroding the quality of life of the inhabitants. Against this backdrop, the prospect of a network of open spaces that were historically a form of commons gains renewed salience and significance. Further study of this threatened heritage and of its potential contribution to quality of life today not only appears timely, but also pressing.

7. Conclusions

The evolution and transformation of pastoral routes in Malta, outlined in this paper, played a crucial but often neglected role in the formation of the archipelago’s cultural landscape. In the introduction, four key reasons were given why they merit study, and why they are relevant to the theme of endangered heritage.

The first and second reasons were both tied to the form of heritage that they represent, and some common conclusions may be drawn for both. The pastoral routes represent a clear departure from conventional forms of heritage, in the traditional sense of monuments that are more easily delimited, yet they are also the cumulative result of the efforts of many generations of largely anonymous individuals, who reshaped landscapes but left a relatively small imprint in the written record. The tangible and intangible heritage values of pastoral routes have been widely recognized on the international scene. In the Maltese context, this has yet to happen, partly because they have fallen into disuse, and partly because their purpose and significance have been largely forgotten.

This brings us to the third reason why the pastoral routes represent an interesting form of threatened heritage. Their material imprint in the landscape is inseparable from the system of practices, rights, and obligations that regulated their use. One of the long-term impacts of their long history of transformations has been the erosion, even erasure, of the concept of commons in the Maltese landscape. In the brief history traced above, a recurring theme is the progressive displacement and overwriting of the legal and conceptual framework that had been the basis for common grazing ground for half a millennium. The loss of this legal and conceptual framework was accompanied by the loss of public rights of access in the landscape, which in turn came hand in hand with the enclosure and repurposing of much of the land that had formerly been commons. Furthermore, as a result of the erasure of the same legal and conceptual framework, the fragments of the pastoral network that still persist in the Maltese landscape are not presently recognized as commons, but are widely held to be government property, as a legacy of the British colonial administration. This has important consequences. The reallocation of former grazing lands for building has sometimes been contested on the grounds of environmental and cultural landscape preservation. However, it has never been contested on the grounds of the public’s right as the historic owner of that land. In short, the loss of memory of historic rights, and the consequent failure to exercise those rights, has paved the way for the loss of the landscape itself.

The above raises a further challenge. The living practices of pastoral activity along these routes have dwindled to the verge of extinction over the past decade, under the pressure of urbanization and increasing regulation. Surviving sections of what was once a continuous network are now divided by cultivated enclosures, busy roads, and urban areas. The intangible practices and associative values attached to the droveways are, as a result, also threatened with extinction, and to a large extent, are only being preserved through ethnographic documentation. The preservation of the material imprint of the pastoral routes on the cultural landscape is, on the other hand, a realistic and attainable goal, which has clear benefits for the citizen.

The fourth reason why pastoral routes were considered an interesting example for study was that they demonstrate how an interdisciplinary perspective is useful, even vital, to address the complexity of the challenges that they present. This paper has advocated and deployed such an interdisciplinary approach, drawing on archaeology, history, ethnography, law, and legal anthropology for a better-informed approach to understanding and managing this element of the cultural landscape today. This paper has also raised new questions for each of these disciplines that require further research, considered in the next section.

8. Future Directions

This paper has traced some key characteristics of the evolution of pastoral routes in Malta, outlining some issues around their management today, and will now consider some challenges for the future. Malta is one of the most densely populated, and most heavily built, territories on the entire planet. Paradoxically, although Malta was among the first countries to sign the European Landscape Convention when it was opened for signature in 2000, at the time of writing (May 2024) it had still not ratified the same Convention, to give it force of law. A plausible explanation for this inordinate delay is a hesitation to regulate the high density of competing interests that jostle over the limited land area available. The long history of contestation over land use that has been traced in this paper has arguably entered its most acute chapter to date, and ratification of the Convention is therefore a more pressing priority than ever.

In such a setting, the safeguarding of open spaces, and of the right to public access and enjoyment of those spaces, is more critical than ever, and essential for the wellbeing of the citizen and the community. The future study and management of the historical pastoral routes considered in this paper need to be informed by these needs, and by principles of equity and responsible stewardship of the landscape. This requires further interdisciplinary research, on the lines advocated in this paper, and on several fronts. The interdisciplinary efforts need to encompass an even wider range of specializations than was possible in the present contribution. Ecology and agricultural science may add vital perspectives on present-day challenges, which may be complemented and enriched by the long-term perspectives provided by paleoecology. Topography, hydrology, surface geology, and soil are key variables that inevitably influenced the decisions that shaped the pastoral route network over time. Each of these areas offers rich scope for further interdisciplinary work. Future approaches also require a paradigm shift, on the lines advocated by Rotherham, to integrate social and economic considerations in the management of landscapes and ecology [68] (p. 439).

The consolidation of administrative and legal measures to coherently safeguard those spaces and rights of access is a high priority for the future. The legal standing of surviving pastoral routes needs to be examined and assessed case by case. Further investigation in collaboration with policy-makers would be necessary to ascertain whether it may be viable to encourage, maintain, and possibly reintroduce traditional pastoral foraging in suitable sectors of the pastoral route network that have not been impacted by urbanization. In other cases, a more viable scenario is the recognition and protection of historic pastoral routes as open spaces for public enjoyment. A Public Domain Act was enacted in Malta in 2016, but to date, implementation on the ground has been very slow. It does nevertheless provide a firm legal basis and the opportunity for the formal recognition of public rights over surviving parts of the former network of pastoral routes.

In order to achieve all the objectives that have just been outlined, and as a basis for further research, a high priority will be the comprehensive spatial mapping of the pastoral route network as recorded in the historic mapping record, and of the present state of its components, to provide a quantifiable spatial record of the various transformations they have undergone, as outlined in this paper.

The comprehensive mapping of the pastoral route network will also be invaluable for the exploration of another aspect that was partially explored in an earlier contribution [19]. This is the analysis of the spatio-temporal and topological characteristics of the network as a system of movement and connectivity. This may be taken further by considering the experiential dimensions of the rhythms and taskscapes of the pastoral activity that the network made possible, drawing on the rich seam of approaches that have bridged archaeological interpretations and ethnographic comparisons, such as Tim Ingold’s work on the temporality of landscape [69], lines of connectivity and wayfaring [70] (pp. 96–103), and the experience of walking and movement across a landscape [71].

Meanwhile, more research is needed to continue to shed light on the role and significance of pastoralism in the shaping of the Maltese landscape. The timeline of the account presented above of the evolution of pastoral routes and their evolution is heavily dependent on the written record. In particular, the chronology of the original emergence of these systems in Malta remains unclear and will require extensive archaeological sampling to complement the written and ethnographic record.

A related avenue of investigation, which may also be pursued further through archaeological analysis complemented by the archival record, is the more detailed charting of the changes undergone by the pastoral routes over time, from their original formation, through the vicissitudes of successive encroachment, urbanization, and obliteration, to their survival and preservation today. A subsidiary question that warrants investigation is the relationship between the morphology of pastoral routes and that of street networks in historic urban spaces, which in some cases may have been built along and around earlier pastoral routes, and in a later period, within them, in both cases preserving their imprint in the urban street plan.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to the conceptualization and writing of this article. G.I.S.-based visualization and design of illustrations was carried out by G.A.; D.E.Z. contributed historico-legal perspectives; K.X. gave inputs on present-day legislation; Ethnographic observations of modern grazing were conducted by N.C.V.; N.C.V. and R.G. conducted the archival research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for all the assistance kindly provided by all the staff at the Records and Archives Section within the Public Works Department (PWD), the National Archives of Malta (NAM), and the Main Library of the University of Malta. They are also grateful to Giovanni Bonello and to Ian Ellis for their kind assistance with Figure 4 and Figure 8, respectively, and to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback on an earlier draft.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rogers, A.P. Values and Relationships between Tangible and Intangible Dimensions of Heritage Places. In Values in Heritage Management: Emerging Approaches and Research Directions; Avrami, E., Macdonald, S., Mason, R., Myers, D., Eds.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 172–185. ISBN 9781606066201. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention; European Treaty Series, No. 176; Council of Europe: Florence, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dejeant-Pons, M. (Ed.) Landscape Mosaics: Thoughts and Proposals for the Implementation of the Council of Europe Landscape Convention; Council of Europe: Florence, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, S.A. The social construction of scale. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E. Europe and the People Without History, 2nd ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780520268180. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Eurostat Statistics Explained: Land Cover Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Land_cover_statistics#Land_cover_in_the_EU_Member_States (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Barker, G. Agriculture, Pastoralism, and Mediterranean Landscapes in Prehistory. In The Archaeology of Mediterranean Prehistory; Blake, E., Knapp, A.B., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Retamero, F.; Schjellerup, I.; Davies, A. (Eds.) Agricultural and Pastoral Landscapes in Pre-Industrial Society: Choices, Stability and Change; Earth 3; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Knodell, A.R.; Wilkinson, T.C.; Leppard, T.P.; Orengo, H.A. Survey archaeology in the Mediterranean world: Regional traditions and contributions to long-term history. J. Archaeol. Res. 2023, 31, 263–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. Honour, Family and Patronage: A Study of Institutions and Moral Values in a Greek Mountain Community; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Mientjes, A.C. Paesaggi Pastorali: Studio Ethnoarcheologico sul Pastoralismo in Sardegna; CUEC Editrice: Cagliari, Italy, 2008; ISBN 8884674786. [Google Scholar]

- Cinà, R.; Massaro, F.P. La transumanza e le trazzere Siciliane. Riv. Agenzia Territ. 2001, 1, 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Caliandro, L.P.; Loisi, R.P.; del Sasso, P. Connections between masserie and historical road systems in Apulia. J. Agric. Eng. 2014, 45, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunce, R.G.H.; De Aranzabal, I.; Schmitz, M.F.; Pineda, F.D. A Review of the Role of Drove Roads (Cañadas) as Ecological Corridors; Alterra-Rapport 1428; Alterra: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2006; Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/fulltext/22779 (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Mattone, A.; Simbula, P.F. (Eds.) La Pastorizia Mediterranea: Storia e Diritto (Secoli XI-XX); Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Transhumance: The Seasonal Droving of Livestock along Migratory Routes in the Mediterranean and in the Alps [Online Video]. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-4941 (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Bevan, A.; Conolly, J. Mediterranean Islands, Fragile Communities and Persistent Landscapes: Antikythera in Long-Term Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, G.; Grima, R.; Vella, N.C. The use of geographical information system and 1860s cadastral data to model agricultural suitability before heavy mechanization. A case study from Malta. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, G.; Grima, R.; Vella, N.C. Locating potential pastoral foraging routes in Malta through the use of a Geographic Information System. In Temple Landscapes: Fragility, Change and Resilience of Holocene Environments in the Maltese Islands; French, C., Hunt, C.O., Grima, R., McLaughlin, R., Stoddart, S., Malone, C., Eds.; McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlow, S. The Archaeology of Improvement in Britain, 1750–1850; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen-Jones, H.; Dewdney, J.C.; Fisher, W.B. (Eds.) Malta: Background for Development; Department of Geography, University of Durham: Durham, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, S.F. Milk pasteurization in Malta. Aust. J. Dairy Technol. 1951, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, A.P.F. Report on a Survey of the Need for Afforestation and Water Conservation in the Waste Land of the Maltese Islands; Government Printing Office: Marsa, Malta, 1952.

- Charlton, W.A. Trends in the Economic Geography of Malta since 1800. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Durham, Durham, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Rippon, S. Historic Landscape Analysis: Deciphering the Countryside; Practical Handbooks in Archaeology 16; Council for British Archaeology: York, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, C.O.; Vella, N.C. A view from the countryside: Pollen from a field fill at Miżieb ir-Riħ. Malta Archaeol. Rev. 2008, 7, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Vella, N.C.; Spiteri, M. Documentary Sources for a Study of the Maltese Landscape. In Storja: 30th Anniversary Edition; Frendo, H., Ed.; Malta University Historical Society: Marsa, Malta, 2008; pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dalli, C. Malta: The Medieval Millenium; Midsea Books: Marsa, Malta, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abela, G.F. Della Descrittione Di Malta Isola Nel Mare Siciliano Con Le Sue Antichita, Ed Altre Notitie; P. Bonacota: Marsa, Malta, 1647. [Google Scholar]

- Ciantar, G.A. Malta Illustrata, Ovvero Descrizione Di Malta, Isola Del Mare Siciliano e Adriatico, Con Le Sue Antichita; Stamperia del Palazzo di S.A.S.: Marsa, Malta, 1772. [Google Scholar]

- Wettinger, G. The village of Ħal Millieri: 1419–1530. In Ħal Millieri: A Maltese Casale, Its Churches and Paintings; Luttrell, A., Ed.; Midsea Books: Marsa, Malta, 1976; pp. 36–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wettinger, G. Early Maltese popular attitudes to the government of the Order of St John. Melita Hist. 1974, 6, 255–278. [Google Scholar]

- Wettinger, G. Agriculture in Malta in the Late Middle Ages. In Proceedings of History Week 1981; Buhagiar, M., Ed.; The Historical Society: Marsa, Malta, 1981; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wettinger, G. Mellieħa in the Middle Ages. In Mellieħa Through the Tides of Time; Catania, J., Ed.; Mellieħa Local Council: Marsa, Malta, 2002; pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Donlan, S.P. Remembering: Legal Hybridity and Legal History. Comp. Law Rev. 2011, 2. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1874088 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Donlan, S.P.; Andò, B.; Zammit, D. “A Happy Union”? Malta’s Legal Hybridity. Tulane Eur. Civ. Law Forum 2012, 27, 165–208. [Google Scholar]

- Ganado, J.M. Maltese Law. J. Comp. Legis. Int. Law Third Ser. 1947, 29, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tamanaha, B. Understanding Legal Pluralism: Past to Present, Local to Global. Syd. Law Rev. 2008, 30, 375–411. [Google Scholar]

- Dalli, C. Governing the Islands: The Universitates of Malta and Gozo. In Malta’s Road to Autonomy: 100 Years on from the 1921 Self-Government; Camilleri, M., Spiteri, M., Eds.; Malta Libraries: Marsa, Malta, 2023; pp. 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dalli, C. Medieval Communal Organisation in an Insular Context: Approaching the Maltese Universitas. In The Making and Unmaking of the Maltese Universitas; A Supplement of Heritage; Midsea Books: Marsa, Malta, 1993; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Universitas Personarum. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/universitas%20personarum (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Universitas Rerum. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/universitas%20rerum (accessed on 6 April 2024).