Community Attachment to AlUla Heritage Site and Tourists’ Green Consumption: The Role of Support for Green Tourism Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Context of AlUla Heritage City, Saudi Arabia

3. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

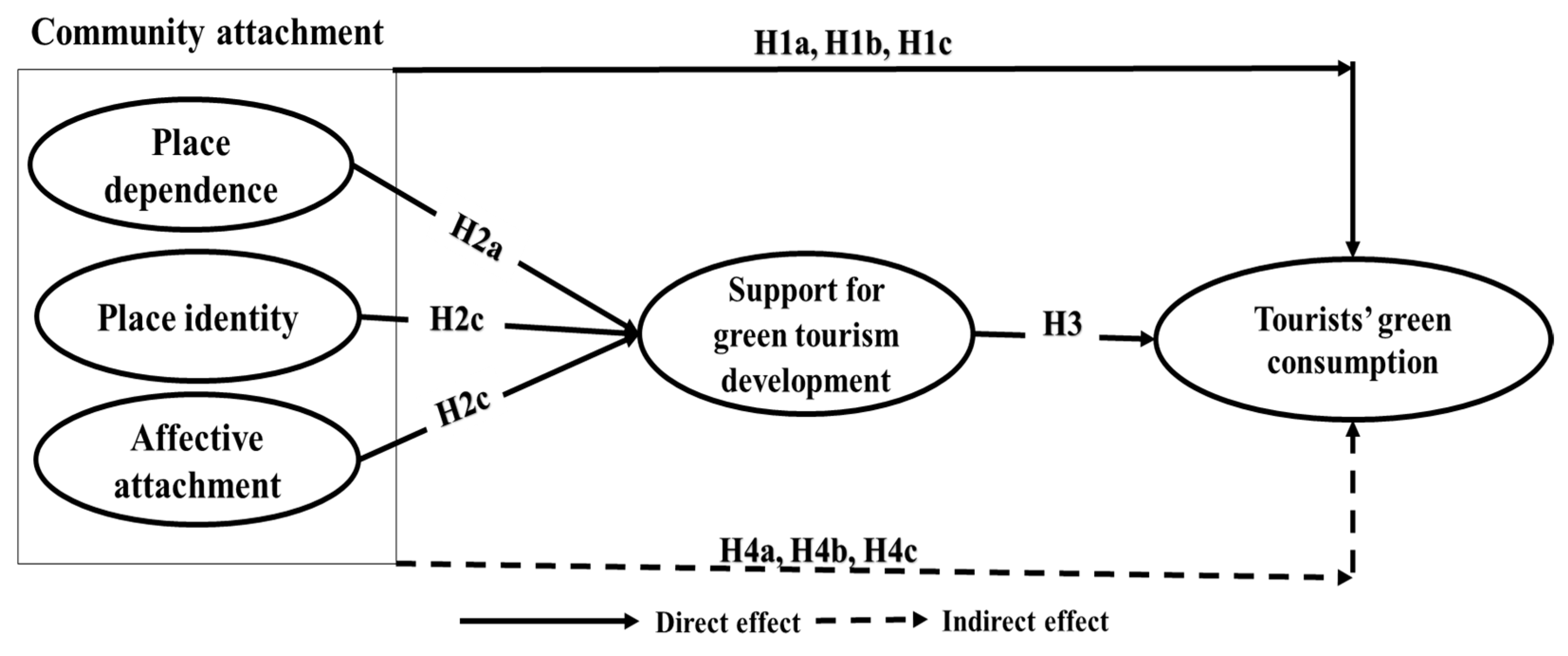

3.1. Community Attachment and Tourists’ Green Consumption (TGC)

3.2. Community Attachment and Support for Green Tourism Development (GTD)

3.3. Support for GTD and TGC

3.4. The Mediating Role of Support for GTD

4. Methods

4.1. Measures

4.2. Collection of Study Data

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

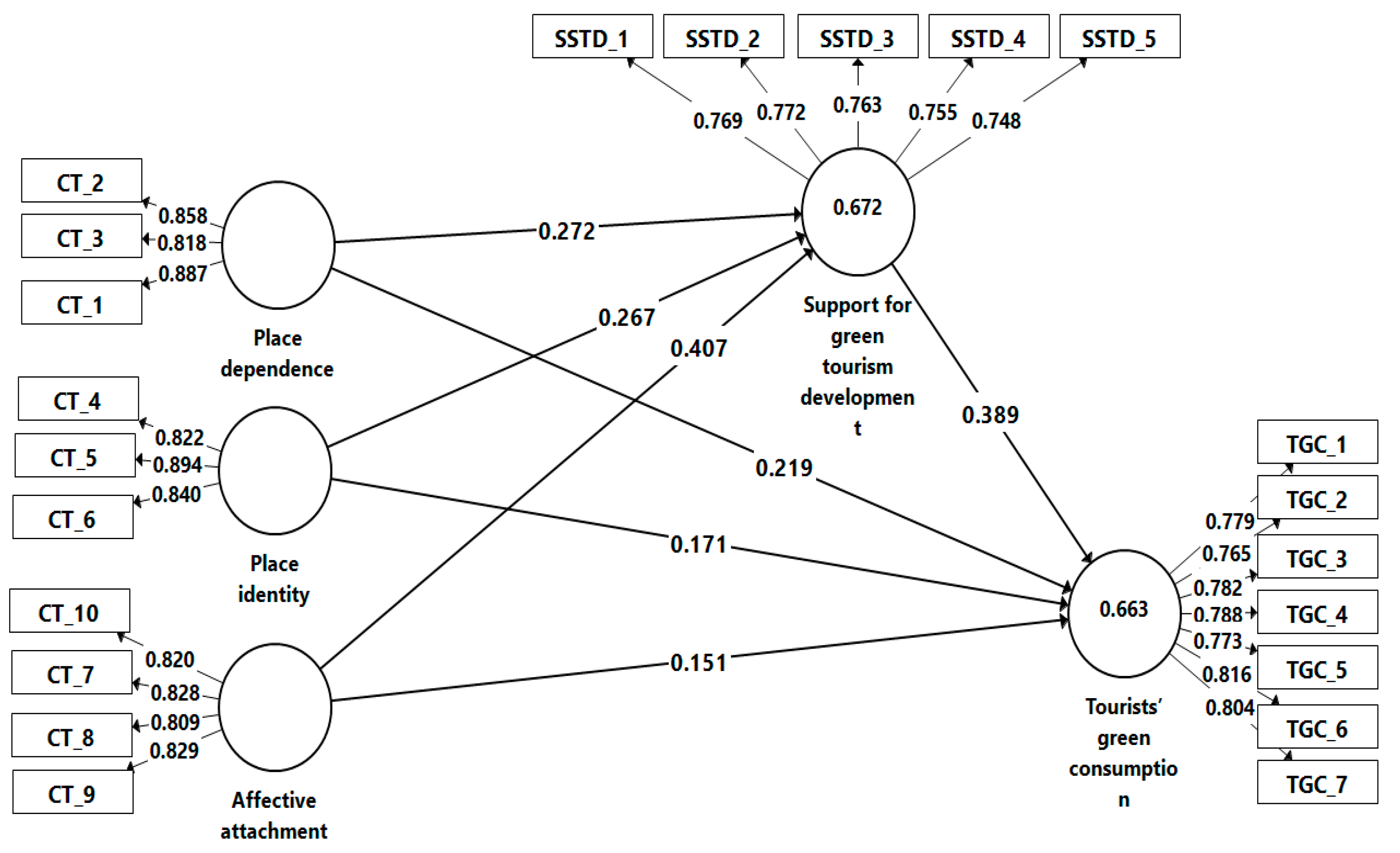

5.1. Measurement Model Outcomes

5.2. Hypothesis Assessment Results

6. Discussion and Implications

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Future Avenues

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Community attachment

- Place dependence.

- Place identity.

- Affective attachment.

- Support for sustainable tourism development.

- Tourists’ green consumption.

References

- Alsahafi, R.; Alzahrani, A.; Mehmood, R. Smarter Sustainable Tourism: Data-Driven Multi-Perspective Parameter Discovery for Autonomous Design and Operations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheeb, S.A.; Zerouali, B.; Elbeltagi, A.; Alwetaishi, M.; Wong, Y.J.; Bailek, N.; AlSaggaf, A.A.; Abd Elrahman, S.I.M.; Santos, C.A.G.; Majrashi, A.A. Enhancing Sustainable Urban Planning through GIS and Multiple-Criteria Decision Analysis: A Case Study of Green Space Infrastructure in Taif Province, Saudi Arabia. Water 2023, 15, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Fahmawee, E.A.; Jawabreh, O. Sustainability of green tourism by international tourists and its impact on green environmental achievement: Petra heritage, Jordan. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2023, 46, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Joppe, M. Promoting Urban Green Tourism: The Development of the Other Map of Toronto. J. Vacat. Mark. 2001, 7, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. Heritage Conservation and Reuses to Promote Sustainable Growth. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 85, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erianda, A.; Alanda, A.; Hidayat, R. Systematic Literature Review: Digitalization of Rural Tourism Towards Sustainable Tourism. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Comput. Eng. 2023, 5, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCU. Initiatives. Available online: https://www.rcu.gov.sa/en/initiatives/ (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism Principles, Practices, Philosophies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 8126513438. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Duffy, L.N.; Moore, D. Importance of Residents’ Perception of Tourists in Establishing a Reciprocal Resident-Tourist Relationship: An Application of Tourist Attractiveness. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Murray, I. Resident Attitudes toward Sustainable Community Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šegota, T.; Mihalič, T.; Perdue, R.R. Resident Perceptions and Responses to Tourism: Individual vs Community Level Impacts. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life Satisfaction and Support for Tourism Development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xiong, L.; Lv, X.; Pu, B. Sustainable Rural Tourism: Linking Residents’ Environmentally Responsible Behaviour to Tourists’ Green Consumption. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.J.; Var, T.; Var, T. Resident Attitudes to Tourism in North Wales. Tour. Manag. 1984, 5, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pfister, R.E. Residents’ Attitudes Toward Tourism and Perceived Personal Benefits in a Rural Community. J. Travel. Res. 2008, 47, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.K.; Chen, H.; Lee, T.J.; Hyun, S.S.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y. The Impacts of Under-Tourism and Place Attachment on Residents’ Life Satisfaction. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecka, M.; Boley, B.B.; Strzelecka, C. Empowerment and Resident Support for Tourism in Rural Central and Eastern Europe (CEE): The Case of Pomerania, Poland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaján, E. Community Perceptions to Place Attachment and Tourism Development in Finnish Lapland. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 490–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G.; Perdue, R.R.; Long, P. Empowerment and Resident Attitudes toward Tourism: Strengthening the Theoretical Foundation through a Weberian Lens. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. Place Attachment, Perception of Place and Residents’ Support for Tourism Development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2018, 15, 188–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Toward a Social Psychology of Place. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P. Meanings of place: Everyday experience and theoretical conceptualizations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshinloye, K.D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Joo, D. The Influence of Place Attachment and Emotional Solidarity on Residents’ Involvement in Tourism: Perspectives from Orlando, Florida. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 914–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytekin, A.; Keles, H.; Uslu, F.; Keles, A.; Yayla, O.; Tarinc, A.; Ergun, G.S. The Effect of Responsible Tourism Perception on Place Attachment and Support for Sustainable Tourism Development: The Moderator Role of Environmental Awareness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C.; Perkins, D.D. Finding Common Ground: The Importance of Place Attachment to Community Participation and Planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2006, 20, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.C. Community Benefit Tourism Initiatives—A Conceptual Oxymoron? Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyara, G.; Jones, E. Community-Based Tourism Enterprises Development in Kenya: An Exploration of Their Potential as Avenues of Poverty Reduction. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Morais, D.B.; Dowler, L. The Role of Community Involvement and Number/Type of Visitors on Tourism Impacts: A Controlled Comparison of Annapurna, Nepal and Northwest Yunnan, China. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Kang, S.K.; Long, P.; Reisinger, Y. Residents’ Perceptions of Casino Impacts: A Comparative Study. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, C.; Lovell, J. The Impact of Hosting Major Sporting Events on Local Residents: An Analysis of the Views and Perceptions of Canterbury Residents in Relation to the Tour de France 2007. J. Sport Tour. 2007, 12, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gursoy, D.; Chen, J.S. Validating a Tourism Development Theory with Structural Equation Modeling. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, P.; Gursoy, D.; Sharma, B.; Carter, J. Structural Modeling of Resident Perceptions of Tourism and Associated Development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, L.N.; Thapa, B.; Ko, Y.J. Residents’ perspectives of a world heritage site. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Rutherford, D.G. Host Attitudes toward Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Han, Y.; Ng, P. Green Consumption Intention and Behavior of Tourists in Urban and Rural Destinations. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2023, 66, 2126–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.T.; Mowen, A.J.; Tarrant, M. Linking Place Preferences with Place Meaning: An Examination of the Relationship between Place Motivation and Place Attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Robinson, G.M. The Influence of Place Attachment, and Moral and Normative Concerns on the Conservation of Native Vegetation: A Test of Two Behavioural Models. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, E.; Emeagwali, O.L.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Al-Geitany, S. Destination Social Responsibility and Residents’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: Assessing the Mediating Role of Community Attachment and Involvement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Howes, Y. Disruption to Place Attachment and the Protection of Restorative Environments: A Wind Energy Case Study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.Y.; Yang, J.-J.; Choi, S.; Lee, Y.-K. Impacts of Residential Environment on Residents’ Place Attachment, Satisfaction, WOM, and pro-Environmental Behavior: Evidence from the Korean Housing Industry. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1217877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivek, D.J.; Hungerford, H. Predictors of Responsible Behavior in Members of Three Wisconsin Conservation Organizations. J. Environ. Educ. 1990, 21, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Chen, J.S.; Ramos, W.D.; Sharma, A. Visitors’ Eco-Innovation Adoption and Green Consumption Behavior: The Case of Green Hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 1005–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The Relations between Natural and Civic Place Attachment and Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Kobrin, K.C. Place Attachment and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 32, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Augustyn, M.M. Testing the Dimensionality of the Quality Management Construct. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2016, 27, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E.A. Pro-Environmental Behaviours and Park Visitors: The Effect of Place Attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Graham Smith, L.D.; Weiler, B. Testing the Dimensionality of Place Attachment and Its Relationships with Place Satisfaction and Pro-Environmental Behaviours: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Relationships between Place Attachment, Place Satisfaction and pro-Environmental Behaviour in an Australian National Park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tokhais, A.; Thapa, B. Management Issues and Challenges of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Saudi Arabia. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, M.A.; Koziol, C. Adobe Fabric and the Future of Heritage Tourism: A Case Study Analysis of the Old Historical City of Alula, Saudi Arabia; University of Colorado at Denver: Denver, CO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pavan, A. A Conceptual Investigation of the Transformation of AlUla into a Global Tourism Destination: Saudi Arabia Rediscovers Its Pre-Islamic Heritage and Bets on Cultural Diplomacy. J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2023, 8, 1152–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Filippi, L.D.; Mazzetto, S. Comparing AlUla and The Red Sea Saudi Arabia’s Giga Projects on Tourism towards a Sustainable Change in Destination Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCU Is Saudi Arabia the Next Big Heritage Tourism Destination? Available online: https://www.rcu.gov.sa/en/media-gallery/articles/is-saudi-arabia-the-next-big-heritage-tourism-destination/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Gallego, J.I.; Margottini, C.; Perissé Valero, I.; Spizzichino, D.; Beni, T.; Boldini, D.; Bonometti, F.; Casagli, N.; Castellanza, R.; Crosta, G.B.; et al. Rock Slope Instabilities Affecting the AlUla Archaeological Sites (KSA). In Progress in Landslide Research and Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 413–429. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Vision, 2030 Discover the Extraordinary Heritage of AlUla—A Living Museum of Sandstone Outcrops, Historic Developments, and Preserved Tombs. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/projects/alula (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Bowlby, J. Attachment Theory, Separation Anxiety, and Mourning. Am. Handb. Psychiatry 1975, 6, 292–309. [Google Scholar]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination Attachment: Effects on Customer Satisfaction and Cognitive, Affective and Conative Loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Shen, Y.L. The Influence of Leisure Involvement and Place Attachment on Destination Loyalty: Evidence from Recreationists Walking Their Dogs in Urban Parks. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J.; Sparks, P. Engaging with the Natural Environment: The Role of Affective Connection and Identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.D.; Virden, R.J.; van Riper, C.J. Effects of Place Identity, Place Dependence, and Experience-Use History on Perceptions of Recreation Impacts in a Natural Setting. Environ. Manag. 2008, 42, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D. People in Places: A Transactional View of Settings. 1981. Available online: https://escholarship.org/content/qt48v387g7/qt48v387g7.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Strzelecka, M.; Boley, B.B.; Woosnam, K.M. Place Attachment and Empowerment: Do Residents Need to Be Attached to Be Empowered? Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the Commodity Metaphor: Examining Emotional and Symbolic Attachment to Place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.L.; Graefe, A.R. Attachments to Recreation Settings: The Case of Rail-trail Users. Leis. Sci. 1994, 16, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Dwyer, L. Residents’ Place Satisfaction and Place Attachment on Destination Brand-Building Behaviors: Conceptual and Empirical Differentiation. J. Travel. Res. 2018, 57, 1026–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Yang, F. Do Motivations Contribute to Local Residents’ Engagement in pro-Environmental Behaviors? Resident-Destination Relationship and pro-Environmental Climate Perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S. Residents’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior and Tourists’ Sustainable Use of Cultural Heritage: Mediation of Destination Identification and Self-Congruity as a Moderator. Heritage 2024, 7, 1174–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. College Youth Travelers’ Eco-Purchase Behavior and Recycling Activity While Traveling: An Examination of Gender Difference. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Martín, A.M.; Ruiz, C.; Hidalgo, M. del C. The Role of Place Identity and Place Attachment in Breaking Environmental Protection Laws. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzell, D.; Pol, E.; Badenas, D. Place Identification, Social Cohesion, and Enviornmental Sustainability. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D.; Juwaheer, T.D. Island Residents’ Identities and Their Support for Tourism: An Integration of Two Theories. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Experiencing Nature: Affective, Cognitive, and Evaluative Development in Children. In Children and Nature: PSYCHOLOGICAL, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; Volume 117151. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The Effect of Destination Social Responsibility on Tourist Environmentally Responsible Behavior: Compared Analysis of First-Time and Repeat Tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. Reputation, Subjective Well-Being, and Environmental Responsibility: The Role of Satisfaction and Identification. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1344–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. Sense of place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners attitudes toward their properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confente, I.; Scarpi, D. Achieving Environmentally Responsible Behavior for Tourists and Residents: A Norm Activation Theory Perspective. J. Travel. Res. 2021, 60, 1196–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Stedman, R.; Luloff, A.E. Permanent and Seasonal Residents’ Community Attachment in Natural Amenity-Rich Areas. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adongo, R.; Choe, J.Y.; Han, H. Tourism in Hoi An, Vietnam: Impacts, Perceived Benefits, Community Attachment and Support for Tourism Development. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2017, 17, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. Influence Analysis of Community Resident Support for Sustainable Tourism Development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G.; Dyer, P. Locals’ Attitudes toward Mass and Alternative Tourism: The Case of Sunshine Coast, Australia. J. Travel. Res. 2010, 49, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, P.M.; Lee, J.-H. Finding Important Factors Affecting Local Residents’ Support for Tourism Development in Ba Be National Park, Vietnam. For. Sci. Technol. 2017, 13, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, H. Influence of Place-Based Senses of Distinctiveness, Continuity, Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy on Residents’ Attitudes toward Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitnuntaviwat, V.; Tang, J.C.S. Residents’ Attitudes, Perception and Support for Sustainable Tourism Development. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2008, 5, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-X.; Choong, Y.-O.; Ng, L.-P. Local Residents’ Support for Sport Tourism Development: The Moderating Effect of Tourism Dependency. J. Sport Tour. 2020, 24, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Wu, M.-Y.; Pearce, P.L. Shaping Tourists’ Green Behavior: The Hosts’ Efforts at Rural Chinese B&Bs. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Duan, X.; Hu, Q. The Impact of Behavioral Reference on Tourists’ Responsible Environmental Behaviors. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.F.B.; Virto, N.R.; Manzano, J.A.; Miranda, J.G.-M. Residents’ Attitude as Determinant of Tourism Sustainability: The Case of Trujillo. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 35, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendakir, M. At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah (Saudi Arabia) No 1329; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leguina, A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 1483377431. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. PLS Path Modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Salvacion, M.; Salehan, M.; Kim, D.W. An Empirical Study of Community Cohesiveness, Community Attachment, and Their Roles in Virtual Community Participation. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2023, 32, 573–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, I. Sustainability of Nature Walking Trails: Predicting Walking Tourists’ Engagement in pro-Environmental Behaviors. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 748–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonincontri, P.; Marasco, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Visitors’ Experience, Place Attachment and Sustainable Behaviour at Cultural Heritage Sites: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Carmen Hidalgo, M.; Salazar-Laplace, M.E.; Hess, S. Place Attachment and Place Identity in Natives and Non-Natives. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Understanding and Managing Tourism Impacts: An Integrated Approach. J. Ecotourism 2011, 10, 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, D. Responsible Tourism: Concepts, Theory and Practice; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2012; ISBN 1845939883. [Google Scholar]

| λ | (a) | (C.R) | (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place dependence | 0.816 | 0.890 | 0.731 | |

| CT1 | 0.887 | |||

| CT2 | 0.858 | |||

| CT3 | 0.818 | |||

| Place identity | 0.811 | 0.889 | 0.727 | |

| CT_4 | 0.822 | |||

| CT_5 | 0.894 | |||

| CT_6 | 0.840 | |||

| Affective attachment | 0.840 | 0.893 | 0.675 | |

| CT_7 | 0.828 | |||

| CT_8 | 0.809 | |||

| CT_9 | 0.829 | |||

| CT_10 | 0.820 | |||

| Tourists’ green consumption (TGC)) | 0.898 | 0.919 | 0.619 | |

| TGC_1 | 0.779 | |||

| TGC_2 | 0.765 | |||

| TGC_3 | 0.782 | |||

| TGC_4 | 0.788 | |||

| TGC_5 | 0.773 | |||

| TGC_6 | 0.816 | |||

| TGC_7 | 0.804 | |||

| Support for STD | 0.819 | 0.873 | 0.580 | |

| SSTD_1 | 0.769 | |||

| SSTD_2 | 0.772 | |||

| SSTD_3 | 0.763 | |||

| SSTD_4 | 0.755 | |||

| SSTD_5 | 0.748 | |||

| Place Dependence | Place Identity | Affective Attachment | SSTD | TGC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT_1 | 0.887 | 0.517 | 0.646 | 0.637 | 0.661 |

| CT_2 | 0.858 | 0.417 | 0.628 | 0.600 | 0.625 |

| CT_3 | 0.818 | 0.438 | 0.526 | 0.563 | 0.466 |

| CT_4 | 0.510 | 0.822 | 0.532 | 0.543 | 0.550 |

| CT_5 | 0.443 | 0.894 | 0.490 | 0.588 | 0.556 |

| CT_6 | 0.418 | 0.840 | 0.456 | 0.525 | 0.500 |

| CT_7 | 0.566 | 0.465 | 0.828 | 0.597 | 0.596 |

| CT_8 | 0.513 | 0.413 | 0.809 | 0.528 | 0.510 |

| CT_9 | 0.595 | 0.477 | 0.829 | 0.645 | 0.584 |

| CT_10 | 0.634 | 0.534 | 0.820 | 0.691 | 0.594 |

| SSTD_1 | 0.575 | 0.538 | 0.627 | 0.769 | 0.502 |

| SSTD_2 | 0.526 | 0.578 | 0.653 | 0.772 | 0.638 |

| SSTD_3 | 0.470 | 0.443 | 0.563 | 0.763 | 0.532 |

| SSTD_4 | 0.566 | 0.453 | 0.582 | 0.755 | 0.636 |

| SSTD_5 | 0.536 | 0.447 | 0.432 | 0.748 | 0.603 |

| TGC_1 | 0.535 | 0.528 | 0.548 | 0.637 | 0.779 |

| TGC_2 | 0.551 | 0.519 | 0.585 | 0.631 | 0.765 |

| TGC_3 | 0.533 | 0.478 | 0.474 | 0.550 | 0.782 |

| TGC_4 | 0.528 | 0.450 | 0.502 | 0.507 | 0.788 |

| TGC_5 | 0.501 | 0.408 | 0.501 | 0.581 | 0.773 |

| TGC_6 | 0.592 | 0.455 | 0.619 | 0.653 | 0.816 |

| TGC_7 | 0.559 | 0.604 | 0.594 | 0.649 | 0.804 |

| AA | PD | PI | SGTD | TGC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 0.822 | ||||

| PD | 0.706 | 0.855 | |||

| PI | 0.578 | 0.536 | 0.853 | ||

| SGTD | 0.754 | 0.703 | 0.649 | 0.761 | |

| TGC | 0.698 | 0.691 | 0.628 | 0.768 | 0.787 |

| AA | PD | PI | SGTD | TGC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | |||||

| PD | 0.843 | ||||

| PI | 0.695 | 0.657 | |||

| SGTD | 0.897 | 0.857 | 0.791 | ||

| TGC | 0.795 | 0.796 | 0.731 | 0.887 |

| Element | VIF | Element | VIF | Element | VIF | Element | VIF | Element | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT_1 | 1.990 | CT_6 | 1.874 | SSTD_1 | 1.898 | TGC1 | 1.976 | TGC_6 | 2.296 |

| CT_2 | 1.796 | CT_7 | 1.899 | SSTD_2 | 1.798 | TGC2 | 1.915 | TGC_7 | 2.087 |

| CT_3 | 1.708 | CT_8 | 1.889 | SSTD_3 | 1.725 | TGC3 | 2.014 | ||

| CT_4 | 1.598 | CT_9 | 1.852 | SSTD_4 | 1.720 | TGC4 | 2.132 | ||

| CT_5 | 2.193 | CT_10 | 1.739 | SSTD_5 | 1.637 | TGC5 | 2.039 | ||

| Tourists’ green consumption | R2 | 0.663 | Q2 | 0.380 | |||||

| Support for sustainable tourism development | R2 | 0.672 | Q2 | 0.362 | |||||

| Paths | β | t | p | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Paths | ||||

| H1a—Place dependence → TGC | 0.219 | 3.714 | 0.000 | ✔ |

| H1c—Place identity → TGC | 0.171 | 2.723 | 0.007 | ✔ |

| H1b—Affective attachment → TGC | 0.151 | 2.065 | 0.039 | ✔ |

| H2a—Place dependence → SSTD | 0.272 | 4.810 | 0.000 | ✔ |

| H2b—Place identity → SSTD | 0.267 | 7.352 | 0.000 | ✔ |

| H2c—Affective attachment → SSTD | 0.407 | 8.146 | 0.000 | ✔ |

| H3—SSTD → SSTD | 0.389 | 6.126 | 0.000 | ✔ |

| Indirect Mediating Paths | ||||

| H4a—Place dependence → SSTD → TGC | 0.106 | 4.204 | 0.000 | ✔ |

| H4b—Place identity → SSTD → TGC | 0.104 | 4.610 | 0.000 | ✔ |

| H4c—Affective attachment → SSTD → TGC | 0.158 | 4.585 | 0.000 | ✔ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshaer, I.A.; Alyahya, M.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S. Community Attachment to AlUla Heritage Site and Tourists’ Green Consumption: The Role of Support for Green Tourism Development. Heritage 2024, 7, 2651-2667. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7060126

Elshaer IA, Alyahya M, Azazz AMS, Fayyad S. Community Attachment to AlUla Heritage Site and Tourists’ Green Consumption: The Role of Support for Green Tourism Development. Heritage. 2024; 7(6):2651-2667. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7060126

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Ibrahim A., Mansour Alyahya, Alaa M. S. Azazz, and Sameh Fayyad. 2024. "Community Attachment to AlUla Heritage Site and Tourists’ Green Consumption: The Role of Support for Green Tourism Development" Heritage 7, no. 6: 2651-2667. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7060126

APA StyleElshaer, I. A., Alyahya, M., Azazz, A. M. S., & Fayyad, S. (2024). Community Attachment to AlUla Heritage Site and Tourists’ Green Consumption: The Role of Support for Green Tourism Development. Heritage, 7(6), 2651-2667. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7060126