Abstract

The Festival of the Patios of Cordoba, declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) by UNESCO in 2012, serves as an emblematic case of how this designation acts as a tourist brand, attracting a greater number of visitors and granting a competitive advantage to the city’s tourist market. This research is focused on analyzing the differences and similarities in the satisfaction, lived experience and behavioral intention of tourists according to their sociodemographic profile during the 2022 edition of the Patios Festival. The study’s main objective is to understand the sociodemographic profile of the tourist who visits this event and if there are features of this profile that influence the satisfaction and lived experience with the event. Using a quantitative methodological approach, field work was carried out during the Fiesta de los Patios of Cordoba (Spain) in its 2022 edition, which took place between 3 and 15 May 2022, obtaining 383 valid surveys. The results reveal differences in the perception and satisfaction of the experience depending on the sociodemographic profile of the visitors. These findings highlight the need to adapt the tourism offerings to improve the visitor experience and also contribute to the scarcity of studies on ICH to help tourism managers formulate strategies that maximize the cultural and economic benefits of these Word Heritage inscriptions.

1. Introduction

Europe’s great cultural and heritage wealth [1] means that knowledge of culture is one of the main motivations for travel, which in turn has led to an increase in cultural tourism in recent years [2]. The Intangible Heritage of Humanity list is one of the three lists published annually by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), with the objective not only of protection, but also of safeguarding, in the sense of ensuring its continuous transmission and recreation [3]. While this is UNESCO’s main objective, the role of such inscriptions as a tourism resource is undeniable [4]. Due to the visibility that this inscription provides, many scientific studies link Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICHs) to increased tourism flows, particularly of international tourists [5,6].

ICHs are an important tourism resource, which in addition to being a force for attracting tourists [7], have another indirect effect, which is that they are used as a tool or starting point for the creation of places and tourist attractions in those places where such inscriptions are located [8]. In other words, the UNESCO declaration of an ICH often means that the place obtains a seal of value that becomes a competitive advantage in the global tourism market [9]. However, this great publicity that comes with inscription raises problems of balance between authenticity and commodification, and the entities in charge of tourism management must take actions that allow for sustainable tourism development in these places [9,10].

The Cordoba Patios Festival was declared an ICH in 2012 as it is considered to “promote the function of the patio as an intercultural meeting place and foster a sustainable collective way of life, based on the establishment of strong social ties and networks of solidarity and exchanges between neighbors, while stimulating the acquisition of knowledge and respect for nature” [11]. As is the case with the other declarations, its declaration leads to an increase in the number of visits due to its greater popularity [12]. Due to the limited number of studies carried out in ICH, this research aims to detect similarities and differences in the tourism profile factors (age, gender, income, educational level and employment status) of the participants of the Fiesta de los Patios in its 2022 edition. In this sense, the research questions that this study aims to answer are the following.

Research Question 1 (RQ1): What is the sociodemographic profile of the tourist who visits La Fiesta de los Patios?

Research Question 2 (RQ2): Are there features of the sociodemographic profile that influence satisfaction, behavioral intention and lived experience?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cultural Tourism

Culture is to be understood according to the definition given by [13] as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features that are characteristic of and specific to a society or a group within a society. In other words, culture does not only encompass artistic and literary expressions, but refers to a broader set of practices including traditions and beliefs. Culture encompasses everything that enables a person to express and learn more about themself. Linked to culture and the interest in its knowledge is the concept of cultural tourism, which is defined by the United Nations International Tourism Organization as a “type of tourism activity in which the essential motivation of the visitor is to learn about, discover, experience and consume the tangible and intangible cultural attractions/products of a tourism destination” [14]. These tourist attractions refer to all those traditions of the place and expressions of culture that are characteristic of a society and that allow people to learn more about the place, the way of life and the beliefs of its inhabitants, with all these aspects including the decisive ones that make a tourist visit the location [1]. Therefore, cultural tourism involves immersing tourists in the art, cultural heritage, thoughts and institutions of another country, city or region [15].

Knowing this motivation is key for local communities, as they will be able to make use of the cultural elements of the place to attract tourists, and, in addition, this cultural tourism should be used to bring the characteristics of the place closer to tourists by explaining its rich heritage [16]. All of these efforts to attract tourists based on their cultural motivation mean that cultural tourism becomes a mechanism for the continuous improvement of cultural resources and the quality of the service provided to tourists to increase tourism flows in these places [1]; it is also proof of the evident relationship between heritage and tourism [17].

Cultural tourism includes both tangible and intangible elements that the destination offers. This is why many authors consider World Heritage Sites (WHS) tourism as a form of cultural tourism [18]. The research carried out on WHS is very extensive; however, the research that relates tourism and WHSs is limited, with some examples such as the research on the patrimonialization of tango in Buenos Aires or on the elaboration of the toquilla straw hat [2]. Despite this, there is currently a trend in scientific research in which research on intangible cultural tourism is taking on greater relevance than that on tangible heritage [19].

2.2. Destination Attributes

The attributes of a destination are defined as the set of elements presented by a destination, which will influence the perception of tourists [20]. Thus, the attributes displayed by a destination will have a direct impact on the destination’s image, as well as on the tourists’ intention to visit and recommend it. In other words, attributes affect tourists’ satisfaction and future behavior [21,22]. Attributes such as the attractiveness of the place are configured as a key in the creation of the cognitive image of the destination. Therefore, the unique attractions of the destination influence the creation of its cognitive and unique image, so much so that the cognitive image is influenced by the rational decisions that tourists make in relation to aspects such as accommodation, accessibility or attraction [21]. Therefore, destination attributes become a competitive advantage of destinations and in this way, tourism managers, in an effort to increase and improve place perception, make destination attributes a major part of tourism planning and tourist attraction strategies. In this way, destinations try to achieve certain attributes as a means to promote tourism in the destination [23]. However, not all attributes have a positive influence on the tourism experience, and therefore not all of them provide a competitive advantage [24]. Thus, the attributes of a destination should be configured in a way that helps to increase tourist attachment.

Such is the importance of the attributes of a destination that research such as that carried out by [25] uses attributes such as accommodation, climate, products and accessibility (among others) to assess tourists’ satisfaction with a destination [26].

Studies such as [27] distinguish between two elements in tourist destinations:

- -

- Those characteristics or attributes that are given by the destination. In this case, reference is made to aspects such as the climate, location, existing heritage, etc. In other words, they are aspects that determine the type of tourist that the destination attracts.

- -

- Those attributes that have been “purposely” designed by tourism operators to attract tourists and to satisfy tourists’ needs.

Destination attributes capable of generating a competitive advantage include food and public safety [28,29] or attributes such as accommodation, reasonable prices, public safety and the possibility of a relaxing holiday [30]. Therefore, following [21], destination attributes can be classified into five different dimensions: accommodation, food and beverage, transport, attractions and public safety.

2.3. Satisfaction and Loyalty

Satisfaction can be defined as the comparison or relationship between tourists’ expectations and the experience [31], so that for authors such as [32], satisfaction involves both cognitive and emotional aspects. Tourist satisfaction is a key aspect in the consolidation of a destination. Obtaining dissatisfaction from visitors to a place not only affects those tourists who experience that feeling, but that dissatisfaction will have a ripple effect affecting other people, who will change their previous perception of the place [33].

Tourist satisfaction is a key aspect in the management of tourist destinations; thus, studies such as that of [34] analyze how the factors that influence the satisfaction of tourists visiting Montañita (Ecuador), concluding that the most valued factors were the location of hotel services and the quality of food and beverages in restaurant services. Other studies, such as that of [35], through the study of measures of centrality, dispersion and the correlation of variables, study the impact of the authenticity of a cultural tourism destination on tourist loyalty and satisfaction, concluding that there is a positive correlation between these variables. [36] reviews the literature on the different factors that influence tourist satisfaction, in addition to conducting fieldwork that allowed them to conclude that tourist satisfaction is strongly affected by factors such as the cultural characteristics of the trip, sociodemographic characteristics and the previous source of information for visiting the destination.

Due to the importance of tourist satisfaction, several studies are found linking tourist satisfaction with the evaluation of the tourist experience [37]. Likewise, both the motivation to travel and the sociodemographic characteristics of tourists are directly related to tourist satisfaction [38]. The study of tourist satisfaction can be carried out for different reasons. For example, it may be of interest for effective advertising [39], as well as to increase loyalty to a destination, as tourist satisfaction is considered one of the ways to explain destination loyalty [40].

2.4. Behavioral Intetion

Behavioral intention refers to the degree to which a person is predisposed to perform a certain behavior [41]. Some studies, such as the one conducted by [42] to find out tourists’ behavioral intention, will use three different items. The first one refers to whether the tourist will recommend the city to others as a holiday destination. The second one refers to whether the tourist will return to the city in the future and the final one refers to whether the tourist will say positive things about the city. It is with these items that the intention to revisit and the intention to recommend can be ascertained.

In the tourism and hospitality marketing literature [43], behavioral intention is considered one of the most important aspects of consumer behavior, being the main construct for predicting future consumer behavior [44]. Furthermore, several studies analyze the relationship between behavioral intention and consumer satisfaction [45]. The destination image that the tourist creates and the affective image that the tourist develops towards the destination will predict the tourist’s behavioral intention [46].

2.5. Sociodemographic Profile

Knowing the sociodemographic profile of heritage tourists is very useful, as it allows to know how these visitors rate the different attributes of the place, which enables the efficient management of the destination, adapting tourism resources for the different tourist groups or segments identified [47]. Several research studies have been carried out in this field, mainly considering the variables of age, gender, income level and education.

Most studies attempt to establish the general profile of heritage tourists. The study carried out by [48] identifies the heritage tourist as a young woman with a high level of education who is either a full-time student or employee.

With regard to the age variable, it is, together with gender, one of the variables on which there is a lack of consensus. Studies such as those by [49] establish a wide range, placing the heritage tourist between 26 and 45 years of age, similar to that indicated by [50]. While authors such as [51] indicate an age between 21 and 35 years, profiling the heritage tourist as a young tourist, a statement which is opposed to that of the authors [52] who indicate ages over 45 years.

Regarding gender, there is no consensus in the scientific literature, with studies indicating a preference for these destinations by men [50,51], while others indicate the opposite [49,52], although in these studies, the preference for these destinations of one gender over the other is small.

In terms of educational level, most studies point to the high educational level of tourists visiting destinations with a rich heritage [49,50,53].

Finally, with respect to income level, there is a consensus in the literature, pointing to the medium, medium-high level [51,52].

Therefore, despite the differences found between the different studies, the heritage tourist can be profiled as a young tourist, with higher education, a high level of education and a medium, medium-high income level. This study aims to contribute to profiling the characteristics of tourists in destinations with a great cultural and heritage wealth, and which have a UNESCO inscription.

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Design and Data Collection

This study is based on data obtained through a questionnaire which was completed by tourists attending the 2022 edition of the Córdoba Patios Festival, which took place between 3 and 15 May 2022, and is one of the main tourist attractions of the city of Córdoba. The total number of valid surveys obtained was 383 surveys. This questionnaire was used to analyze tourists’ perceptions of both the Fiesta de los Patios and Cordoba as a tourist destination. The formulation of the items was based on previous research to ensure the validity of the questionnaire [49,54,55]. The items used to create the questionnaire are inspired by various studies related to the study of cultural tourism [54,55]. Likewise, a 7-point Likert scale has been used, since it is considered that the results obtained with it are more precise than with the use of the 5-point Likert scale [56]. The 7-point Likert scale has been successfully used in previous studies on cultural tourism that analyze the satisfaction, perception and intention of future behavior of these cultural tourists [57]. The development of the questionnaire was carried out in three different phases. Firstly, after having selected the relevant scientific literature on the topic to be addressed, the items were evaluated by an expert in heritage tourism in the city of Córdoba. Secondly, local tourism managers reviewed the selected items. Finally, a pilot study was carried out with 25 tourists to make the final adjustments. After these three phases, the questionnaire was refined to avoid questions that generated doubts and to make the questionnaire as clear as possible, avoiding the questionnaire from being excessively long and trying to make the questions as specific as possible to achieve quality results [58].

Convenience sampling was used to collect the sample, which is commonly used in this type of research, in which tourists are available to be surveyed in a specific space and time [59]. Because there were no previous studies to support stratification by gender, age or any other variable, no stratification was conducted. The refusal rate of the questionnaire was low and not significant for any question. Assuming simple random sampling and infinite population, the sampling error would be 5.01%, with a reliability rate of 95%. The level of significance used was a p-value < 0.05, which is shown in the results for each of the items.

The questionnaire was made up of two blocks. The first block contained a group of questions, measured on a 7-point Likert scale, which analyzed the perception and satisfaction of tourists with both the city of Cordoba and their participation in the Fiesta de los Patios. On the other hand, the second block of the questionnaire consisted of a set of questions relating to the sociodemographic profile of the tourists surveyed, such as gender, age, income level, educational level and employment situation.

3.2. Analysis Method

SPSS Statistics v28 was used for the statistical analysis of the data. Subsequently, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov [60,61] and Shapiro–Wilk [62] normality tests were performed on the questionnaire, both confirming that the sample did not correspond to a normally distributed population for all questions (p-value < 0.05). Therefore, it was decided to use non-parametric tests. Since the samples were independent, it was considered appropriate to use the Mann–Whitney (MW) U-test to compare two samples [63], and in cases with more than two samples, the Kruskal–Wallis (KW) test was used [64]. In the latter case, an additional analysis was also performed by applying the U-test (MW) to all possible combinations of pairs of samples. The MW and KW tests are commonly used to identify statistically significant differences between groups of data according to variables.

4. Results

4.1. Research Question 1

In relation to the sociodemographic profile, the different variables (gender, income, age, academic training, daily spend and employment status) are shown in Table 1. In the gender variable, the presence of women is slightly higher than that of men, although it is a variable in which there is relative parity. In relation to the age variable, the age range that stands out most is between 18 and 35 years of age. It is also noteworthy that almost 85% of the participants in this event are under 55 years of age, which indicates that this event has a greater diffusion and popularity among young people. The average household income is medium-high, mainly between EUR 1000 and EUR 2500. On the other hand, most of the participants in the Fiesta de los Patios were university graduates (72.85%) and employed (78.59%). Finally, in relation to the variable of daily expenditure, which is very important to know the economic effect that this event has on the city of Cordoba, this is mainly between EUR 0 and EUR 100 per day, although the range of EUR 200 or more per day also had a high response.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile.

Therefore, it can be concluded that the profile of the tourist participating in the Fiesta de los Patios in the year 2022 was that of a female university graduate, under 35 years of age, who is in employment and with a medium-high income.

4.2. Research Question 2

The questions that formed part of the survey are presented in Table 2, together with the mean and standard deviation of each of these questions. The questionnaire is grouped into four thematic sections: destination, event, perception and finally experience and behavior intention. In general terms, all of the questions have a high score, and it is noteworthy that in no case is the average rating of the tourists participating in the Fiesta de los Patios lower than 5 points, with the sole exception of question E11, regarding the waiting time to start the visit. On the other hand, the highest averages were obtained in the section on the evaluation of the Fiesta de los Patios as an event, specifically the questions relating to the beauty of the patios as a whole and their surroundings, their state of conservation and cleanliness, and the safety felt during the visit (E03, E04, E05 and E10). This highlights the potential of this event, given the image it projects and how it is perceived by tourists.

Table 2.

Set of questions.

Regarding the block of questions relating to perception, question P02, about the emotion felt during the visit, is noteworthy. There are several studies that highlight how in cultural tourism activities, the various emotions generated give rise to the configuration of existential experiences [65].

Table 3 shows those questions where significant differences by gender were found. To include the questions, the criterion was to select those whose p-value was equal to or less than 0.05. Although in general terms all the scores are very high, both for men and women, those questions in which there is the greatest difference between the assessments of both genders are the following. First, the question on the state of conservation of the monumental and historical heritage of the city of Cordoba (D02) showed a greater sensitivity on the part of women towards artistic preservation. Second, the questions relating to the attention and quality of tourist accommodation (D06) and public safety (D12) indicated the greater importance given by women to these aspects during their experience. Third, the question referring to tourist information points and signposting (E08), where the higher rating by women may suggest a greater importance of tourist orientation for them. Finally, differences were also found in the question on the emotion felt during the visit (P02), which shows the greater emotional connection of women with the experience. In all questions, the scores given by women were higher than those given by men.

Table 3.

Mann–Whitney’s U test of the question compared by gender.

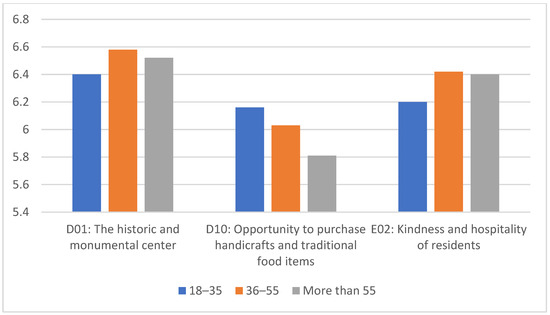

The significant differences found by age are reflected in Table 4 and in Figure 1. As a consequence of there being more than two age groups, a KW test was performed to check the differences between the groups, and subsequently a pairwise MW analysis was performed. As can be seen, significant differences were found between the 18–35 age group and the 36–55 and over 55 age groups, but in no case between the 36–55 and over 55 age groups. What can be seen from this table is the more critical spirit of the younger visitors with respect to the variables relating to the historic and monumental quarter (D01) and the friendliness and hospitality of the residents (E02). However, visitors between 18 and 35 years of age rate the opportunity to buy traditional crafts and food items (D10) higher than those over 55 years of age.

Table 4.

Kruskal–Wallis’ test and Mann–Whitney’s U test pairwise of the question compared by age.

Figure 1.

Significant differences by age.

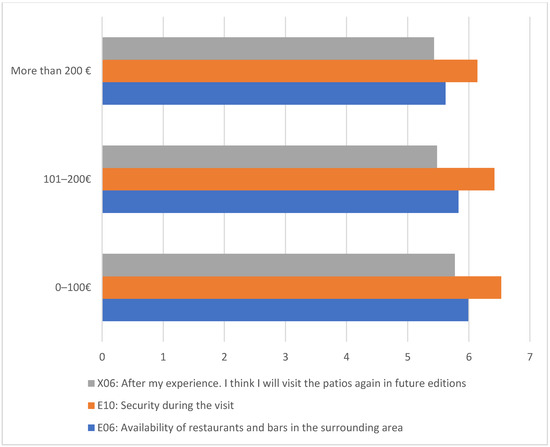

Table 5 and Figure 2 show the questions that show significant differences because of the average daily expenditure; in the same terms as in Table 4, while as there were 3 groups for this variable, a KW test was carried out to see the differences between the groups, as was a subsequent analysis using the MW pairs. The aspects in which significant differences were found for this variable were the perception of the availability of restaurants and bars (E06), safety during the visit (E10), and the intention to visit the event again in future editions (X06). The importance of satisfaction with the gastronomic offer (E06) and perceived safety (E10) by visitors with different levels of expenditure stands out, mainly the latter. In these two areas, people with a higher daily expenditure tended to rate these variables significantly lower than those whose average daily expenditure was in the lower range.

Table 5.

Kruskal–Wallis’ test and Mann–Whitney’s U test pairwise of the question compared by daily spend.

Figure 2.

Significant differences by daily spend.

In relation to educational level, the differences found between non-university graduates (primary and secondary education) and university graduates are reflected in Table 6. In general terms, in all the variables studied, non-university graduates tend to give a more positive assessment than those with university degrees, which shows a more critical spirit on the part of the latter group. Specifically, those questions in which the differences are greater between these two groups are those relating to the accessibility of the patios and surrounding areas (E01), the waiting time for the initial visit (E11) and the intention to visit the patios again in future editions (X06). These differences will be relevant in that they should be taken into consideration when studying visitor satisfaction and perception, and it is important to consider the impact of educational level on the assessment and evaluation of the tourism experience. Regarding the monthly household income level variable (INC), no significant differences were found between the different income ranges considered (less than EUR 1000, between EUR 1000 and EUR 2500 and more than EUR 2500).

Table 6.

Mann–Whitney’s U test of the question compared by educational level.

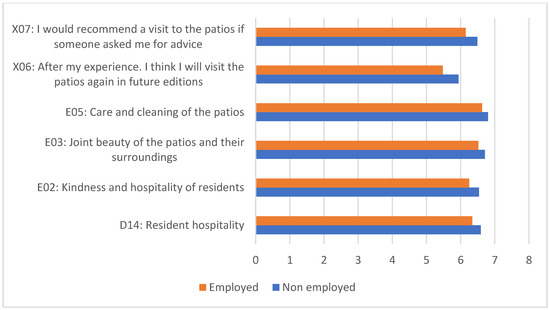

Regarding the employment status variable, two groups were compared: those in employment (public sector, private sector or self-employed) and those not in employment (unemployed, students, retired and people working in the home). Table 7 and Figure 3 show that in those questions where significant differences were found for this variable, the evaluations of the unemployed were more positive than those of the employed. The biggest differences were found mainly in the experience block, specifically in the intention to revisit in future editions (X06) and the recommendation to third parties (X07), which shows greater loyalty, both in terms of revisiting and recommendation of those not in employment. Also noteworthy is the higher score of non-employees on the questions relating to residents’ hospitality and friendliness (D14 and E02).

Table 7.

Mann–Whitney’s U test of the question compared by employment status.

Figure 3.

Significant differences by employment status.

In summary, it can be said that unemployed people compared to employed people have a more positive perception in terms of the hospitality and friendliness of the residents, the beauty of the patios and the care and cleanliness, as well as the highest intention to revisit and recommend. These results can be very useful to understand how employment status influences the tourism experience and perception.

Table 8 shows the questions considered relevant in this study, presenting the relationship with the items of the sociodemographic profile in which significant statistical differences were observed between the groups that make up each of the items. One aspect to note is that the determining variable in a greater number of questions is the educational level (ATR), although the gender variable (GEN) is also a determining variable for a large number of questions. In contrast, monthly household income (INC) does not appear in any of the questions, as there are no significant differences in any of the ranges considered. It should also be noted that the daily expenditure variable (DSP), although it does appear as a variable that shows significant differences in some questions, is only relevant in the section on the evaluation of the Fiesta de los Patios event, and in the section on the lived experience, specifically in the intention to revisit.

Table 8.

Questions presenting significant statistical differences by sociodemographic profile items.

This summary provides an overview of the sections in which significant differences have been found in the perception of the tourist experience according to different sociodemographic characteristics. This will be of great use when developing tourism improvement strategies.

5. Discussion

The results obtained in this study shown in Table 9, in which they are related to the review of the existing literature, showed regarding the sociodemographic profile reinforce the greater presence of women in destinations with great heritage and cultural richness. This aspect is in line with research such as that carried out by [15,49]. However, this is an aspect on which, as detailed in the literature review, there is no clear consensus, with a large group of authors defending the greater presence of men in this type of destination. The profile of young tourists is also in line with the research of [55]. Regarding the level of education, this research corroborates that visitors to places with the WHS or ICH inscription by UNESCO are mainly people with a university degree, which is also affirmed in much of the existing research in this field [50,52].

Table 9.

Discussion.

One of the aspects highlighted in this research is the greater critical nature of younger people and those with university studies, which confirms what has already been stated in other research [66].

In relation to the importance of emotions in shaping the tourist experience, this research is in line with the research carried out by the authors [65]. Among the questions asked to the respondents, the score that stands out is that awarded to the emotion felt during the visit, which reinforces the literature in this field, since different studies point out the crucial importance of the emotions felt during the visit to places with cultural and heritage wealth in the creation of unique experiences [65]. Aspects such as pleasure, disconnection or excitement are feelings that are frequently associated with tourism [67]. Their importance is such that they are often considered indicators of satisfaction during the visit and intention to visit in the future [68].

The causality between emotions and felt satisfaction is latent in this research, since after expressing the felt emotions, they show high satisfaction with the event and loyalty towards it, manifested in the form of a recommendation and intention to visit in the future.

Regarding gender differences, one of the main results obtained has been the greater emotional connection of women with the destination, which is in line with research such as that carried out by [69], who highlights the fact that women are more emotional in tourist destinations. This greater emotional connection of women can be explained with previous research that supports the idea that women show and recognize feelings more easily and that they feel emotionally closer to their environment, a difference from the male gender, which is a more rational analysis [70].

Likewise, in the results, it can be seen how women, in addition to feeling more emotionally connected to the event, show greater loyalty towards it than men, both in terms of revisits and recommendations. These two aspects are linked by various research, which highlights the fact that the emotion transmitted by the place, brand or destination has positive effects on the loyalty created [71].

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Conclusions

Cultural heritage and specifically the places inscribed by UNESCO as locations of Intangible Heritage of Humanity are a key tourist resource for the destinations that obtain this accolade. Not only does it entail its protection, but this registration implies an increase in tourist flows [15], which is demonstrated in the event of the Fiesta de los Patios (Córdoba).

The research presented highlights the results that should be taken into account, since after having related the different questions to the items of the sociodemographic profile, it can be revealed that the determining variable in a great number of questions is educational level, although gender is also a determining variable in a large number of questions. On the other hand, with respect to monthly household income, no significant differences were found in any of the ranges considered. It should also be noted that the daily expenditure variable, although it does appear as a variable that shows significant differences in some questions, is only relevant in the section on the evaluation of the Fiesta de los Patios event and in the section on the experience, specifically in the intention to revisit. As far as gender is concerned, women have shown a greater sensitivity towards artistic preservation and conservation, valuing aspects such as security and attention in the accommodation more highly. Likewise, women show a greater emotional connection with the visit. Regarding the age variable, it is striking that young people between 18 and 35 show a more critical attitude towards aspects such as the friendliness and hospitality of the residents and the appreciation of the historic and monumental center. In addition, they are more appreciative of the opportunity to buy traditional crafts. Likewise, people without a university education are more positive about waiting times and accessibility, while university graduates are more critical. In relation to the sociodemographic profile, it could be concluded that the profile of the tourist who comes to this UNESCO’s ICH event corresponds to that of a young woman with a university degree, who is employed and has a medium-high income.

6.2. Practical Implication

The results obtained are very useful for local authorities and organizers of this event, as they are the key to tailoring tourism strategies to the needs and preferences of different demographic groups, thus improving overall tourist satisfaction. Knowing these data, measures can be taken to increase the satisfaction of those sociodemographic groups whose scores are lower.

Knowing the sociodemographic profile of assistants has many uses: Firstly, it allows to design tourism policies and offer services adapted to the requirements of potential clients. Secondly, it serves to implement continuous improvements to increase satisfaction and loyalty towards the destination, and thirdly, it gives the possibility of creating tourism strategies aimed at attracting people whose profile is different from those who usually visit the city, thus guaranteeing the attraction of tourists with different sociodemographic profiles. That is, knowing the sociodemographic profile allows it to be used as a basis for tourism promotion campaigns, contributing to their effectiveness.

Likewise, the tourist position in which this event finds itself after its declaration and which has been reflected in the research makes it necessary to promote responsible and sustainable tourism policies, to avoid the overcrowding of the event. Examples of these could be encouraging visits to lesser-known patios further away from the center, encouraging attendance at times other than peak hours, or establishing entrances to limit mass influx, since currently it is a free event.

This study constitutes a post-event evaluation that provides data on the lived experience, satisfaction and behavioral intention, so that its comparison with previous studies makes continuous improvement possible.

6.3. Limitations

In relation to the limitations offered by the results of this study, it is necessary to consider the following aspects. The study is based on convenience sampling, so the results may not be representative of the entire population of visitors, in addition to offering a bias in relation to the people who were available and willing to participate at the time of the collection. On the other hand, the period to carry out the field work was limited to the days that the event lasted. Furthermore, providing the questionnaire to tourists while they wait to access a patio is a reflection of the long waiting times to begin the visit, something that has been reflected in the results.

6.4. Future Lines of Research

The following are suggested as future lines of research:

- (1)

- Carry out an analysis of the different dimensions of perception and attributes, which will serve as a basis for segmenting tourists through a cluster analysis.

- (2)

- Apply predictive methodologies, such as structural equation systems based on PLS-SEM and multi-layer perceptron-type artificial neural networks (ANN).

- (3)

- Expand the spectrum of the analysis to the perception by the residents of the city of Córdoba at the level of heritage conservation, economic, social, environmental and identity of the city’s residents with the Intangible Heritage.

- (4)

- Address, from a broader perspective, the study of the event and its relationship with heritage conservation, through qualitative interviews and focus group methodology, collecting the opinions of local officials, as well as the owners of the patios and businesses of the neighborhoods where the event is held.

- (5)

- Conduct research in future editions to identify possible changes in the behavior of tourists and their perceptions.

- (6)

- Connect the results obtained with other research on similar events.

6.5. Main Contribution of the Study

The main contribution of this study lies in the detailed analysis of the sociodemographic profile of the visitors to the Fiesta de los Patios. Enriching the academic literature in this sense provides a clear line of action to promote public–private collaboration between local authorities responsible for the management and conservation of intangible heritage, hand in hand with companies in charge of attracting tourists to the destination. Having identified this target audience, their perceptions and satisfaction, therefore, facilitates the optimization of resources and contributes to sustainable management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.E.R.-R. and M.A.-R.; methodology, L.G.-G. and L.C.-P.; software, J.E.R.-R. and L.G.-G.; validation, L.C.-P. and L.G.-G.; formal analysis, M.A.-R. and L.C.-P.; investigation, J.E.R.-R., L.C.-P., M.A.-R. and L.G.-G.; resources, L.G.-G. and J.E.R.-R.; data curation, L.C.-P. and L.G.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.E.R.-R. and M.A.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.E.R.-R., M.A.-R., L.G.-G. and L.C.-P.; visualization, L.G.-G.; supervision, L.C.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leite, F.C.D.L.; Ruiz, T.C.D. O turismo cultural como desenvolvimento da atividade turística: O caso de Ribeirão da Ilha-Florianópolis (SC). In VII Fórum Internacional de Turismo do Iguassu; Foz do Iguaçu: Paraná, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Prada-Trigo, J.; Pérez Gálvez, J.C.; López-Guzmán, T.; Pesantez, S. Tourism and motivation in cultural destinations: Towards those visitors attracted by intangible heritage. Almatourism-J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2016, 7, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización de la Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, 7th ed.; Organización de la Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, M. Intangible cultural heritage in tourism: Research review and investigation of future agenda. Land 2022, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortul, M.; Elías, S.; Leonardi, V. World heritage sites, international tourism demand and tourist specialization in Latin America and the Caribbean 1995–2019. JTA 2022, 29, 72–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzman, T.; González Santa-Cruz, F. International tourism and the UNESCO category of intangible cultural heritage. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, Z.; Xu, S.; Law, R.; Liao, C.; He, W.; Zhang, M. A Bibliometric Analysis of Research on Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Using CiteSpace: The Perspective of China. Land 2022, 11, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Liang, X.; Zuo, Y. Identifying European and Chinese styles of creating tourist destinations with intangible cultural heritage: A comparative perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 25, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Whitford, M.; Arcodia, C. Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: The intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives. In Authenticity and Authentication of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertoni, P. Mercantilización y autenticidad en la frontera uruguayo-brasileña: El portuñol en el siglo XXI. Trab. Linguística Apl. 2021, 60, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage; Servicio de publicaciones de la Organización Mundial del Turismo: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.; González Santa Cruz, F. The Fiesta of the Patios: Intangible cultural heritage and tourism in Cordoba, Spain. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2016, 11, 182–192. [Google Scholar]

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. In Proceedings of the World Heritage Committee, Eighth Ordinary Session, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 29 October–2 November 1984; UNESCO. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/1984/sc-84-conf004-inf3e.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Organización Mundial del Turismo. Definiciones de Turismo de la OMT; OMT: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284420858 (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Nguyen, T.H.H.; Cheung, C. The classification of heritage visitors: A case of Hue City, Vietnam. J. Herit. Tour. 2014, 9, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santana, J.C.; Maracajá, K.F.B.; de Araújo Machado, P. Turismo cultural y sostenibilidad turística: Mapeo del desempeño científico desde Web of Science. Tur. Soc. 2021, 28, 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Manjavacas Ruiz, J.M. Patrimonio cultural y actividades turísticas. Aproximación crítica a propósito de la Fiesta de Patios de Cordoba. Rev. Andal. Antropol. 2018, 15, 127–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, B.A. Franchising our heritage: The UNESCO World Heritage brand. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A. A framework of tourist attraction research. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H.; Devi, A. Destination Attributes and Destination Image Relationship in Volatile Tourist Destination: Role of Perceived Risk. Metamorphosis 2015, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangpikul, A. The effects of travel experience dimensions on tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: The case of an island destination. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 12, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, G.; Butler, R.; Bennett, M. Positive tourism image perceptions attract travellers—Fact or fiction? The case of Beijing visitors to Macao. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Destination attributes influencing Chinese travelers’ perceptions of experience quality and intentions for island tourism: A case of Jeju Island. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valduga, M.C.; Breda, Z.; Costa, C.M. Perceptions of blended destination image: The case of Rio de Janeiro and Brazil. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2019, 3, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, C.; Deb, S.K.; Hasan, A.A.T.; Khandakar, M.S.A. Mediating effect of tourists’ emotional involvement on the relationship between destination attributes and tourist satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021, 4, 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G.; Amore, A. Tourism and Resilience: Individual, Organisational and Destination Perspectives; Channel View Publications: St Nicholas House, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, M.T.H.; Yeung, E.; Leung, R. Understanding tourists’ policing attitudes and travel intentions towards a destination during an ongoing social movement. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 6, 874–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabphet, S. Applying importance-performance analysis to identify competitive travel attributes: An application to regional destination image in Thailand. J. Community Dev. Res. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2017, 10, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, A.; Rowe, G.; McKee, M. Patients’ experiences of their healthcare in relation to their expectations and satisfaction: A population survey. J. R. Soc. Med. 2013, 106, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bosque, I.R.; San Martín, H. Tourist satisfaction a cognitive-affective model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, A. Patrimonio inmaterial, recurso turístico y espíritu de los territorios. Cuad. Tur. 2011, 27, 663–677. [Google Scholar]

- Carvache Franco, W.; Torres Naranjo, M.; Carvache Franco, M. Análisis del perfil y satisfacción del turista que visita montañita–Ecuador. Cuad. Tur. 2017, 39, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyola Aguilar, L.Y.; Campón-Cerro, A.M. La percepción de la autenticidad del destino cultural y su relación con la satisfacción y lealtad. ROTUR. Rev. Ocio Tur. 2016, 11, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrivar, R.B. Factors that influence tourist satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Res. (Online) 2012, 12, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Du, G.; Wei, Y. The effects of involvement, authenticity, and destination image on tourist satisfaction in the context of Chinese ancient village tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romao, J.; Neuts, B.; Nijkamp, P.; Van Leeuwen, E. Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation: A structural analysis of the motivation and satisfaction of tourists in Amsterdam. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battour, M.; Battor, M.; Bhatti, M.A. Islamic attributes of destination: Construct development and measurement validation, and their impact on tourist satisfaction. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.N.M.; Mohamad, M.; Ghani, N.; Afthanorhan, A. Testing mediation roles of place attachment and tourist satisfaction on destination attractiveness and destination loyalty relationship using phantom approach. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Ye, B.H.; Xiang, J. Reality TV, audience travel intentions, and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K.; Gamage, T.C.; Hameed, W.U.; Qumsieh-Mussalam, G.; Chaijani, M.H.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Kallmuenzer, A. How self-gratification and social values shape revisit intention and customer loyalty of Airbnb customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 100, 103093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga Sánchez, R.; López, F.M.; García Ordaz, M.; Sánchez-Franco, M.J.; Yousafzai, S.Y. Adoption of online social networks to communicate with financial institutions. J. Promot. Manag. 2017, 23, 228–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetanah, B.; Teeroovengadum, V.; Nunkoo, R.S. Destination satisfaction and revisit intention of tourists: Does the quality of airport services matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshardoost, M.; Eshaghi, M.S. Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menor-Campos, A.; Fuentes Jiménez, P.A.; Romero-Montoya, M.E.; López-Guzmán, T. Segmentation and sociodemographic profile of heritage tourist. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 26, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Roda, J.; Gómez-Casero, G.; Medina-Viruel, M.J.; López-Guzmán, T. Categorización del Turista Patrimonial. El Caso de Granada (España); Fundación Dialnet: Logroño, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Remoaldo, P.C.; Vareiro, L.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Santos, J.F. Does gender affect visiting a World Heritage Site? Visit. Stud. 2014, 17, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, C.; Camarero, C.; Laguna-García, M. Towards a new approach of destination royalty drivers: Satisfaction, visit intensity and tourist motivation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Huang, S. Understanding Chinese cultural tourists: Typology and profile. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramires, A.; Brandao, F.; Sousa, A.C. Motivation-based cluster analysis of international tourists visiting a World Heritage City: The case of Porto, Portugal. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira- Gregori, P.E.; Martín, J.C.; Oyarce, F.; Moreno-García, R. Turismo y patrimonio. El caso de Valparaíso (Chile) y el perfil del turista cultural. PASOS. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2019, 17, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B. Towards a classification of cultural tourists. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 4, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Kozak, M.; Ferradeira, J. From tourist motivations to tourist satisfaction. Int. J. Culture. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, H.J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Análisis Multivariante; Prentice Hall: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Z.; Harrison, D.E.; Hair, J. Data Quality Assurance Begins Before Data Collection and Never Ends: What Marketing Researchers Absolutely Need to Remember. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 63, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, M.; Elliott-White, M.; Walton, M. Tourism and Leisure Research Methods: Data Collection, Analysis and Interpretation; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2000; ISBN 9780582368712. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov, A. Determinazione empirica di una lgge di distribuzione. Inst. Ital. Attuari Giorn. 1952, 4, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, N. Table for estimating the goodness of fit of empirical distributions. Ann. Math. Stat. 1948, 19, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.T.H.; Tran, H.L.; Dao, M.N.; Trang, D.T.M. Tourist loyalty and intangible cultural heritage: Casestudy in Danang, Vietnam. Ann. For. Res. 2023, 66, 234–256. [Google Scholar]

- Solano-Sánchez, M.Á.; Arteaga-Sánchez, R.; Castaño-Prieto, L.; López-Guzmán, T. Does the Tourist’s Profile Matter? Perceptions and Opinions about the Fiesta De Los Patios in Cordoba, Spain. Enlightening Tour. A Pathmaking J. 2022, 12, 436–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Measuring emotions in real time: Implications for tourism experience design. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; Van Der Veen, R.; Huang, S.; Deesilatham, S. Mediating effects of place attachment and satisfaction on the relationship between tourists’ emotions and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, S.; Hirose, M. Does gender affect media choice in travel information search? On the use of mobile Internet. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, K.; Ilyas, G.B.; Umar, Z.A.; Tajibu, M.J.; Junaidi, J. Consumers’ awareness and loyalty in Indonesia banking sector: Does emotional bonding effect matters? J. Islam. Mark. 2023, 14, 2668–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).