Abstract

The conservation of cultural heritage is a well-established fact recognized by public administrations, the scientific community, and society at large. Understanding this heritage strengthens the historical memory of communities. However, there is a type of heritage that, as it disappears or evolves over time, cannot be physically recovered: the urban fabric of historic cores. This article aims to implement a system for integrating historical urban data into a Geographic Information System (GIS) to enable the graphic recovery of urban evolution within a territory. This system facilitates the storage of alphanumeric and graphic data in a centralized database, providing a holistic view of the transformation process of a historic center’s landscape. This case study focuses on an area in the historic center of Valencia, a territory influenced by multiple cultures since the city was founded by the Romans. Each culture has altered the spatial structures within the area. Georeferenced documents from historical archives, historical cartography, and the scientific literature were utilized for this study. The results have been integrated into the current cartography of Valencia in the GIS, producing plans of successive urban stages through the overlay of historical maps and current cartography.

1. Introduction

The urban layout of historic city centers has undergone numerous transformations over the years. Improvements in sanitation, changes in transportation methods, and the evolving uses of buildings that define streets and squares, as well as the various cultures that have colonized a city, all contribute to the continual alteration of its urban patterns. These changes, which are integral to a city’s history, are often unknown and can only be rediscovered through historical cartography, drawings, and architectural plans of the buildings that once comprised them [1]. This graphical information makes it possible to observe and analyze how different urban layouts and buildings from various periods overlap and overwrite each other, shaping an urban center as a “palimpsest” where traces of past urban patterns can still be seen today [2]. The graphic reconstruction of such elements is crucial as the first step toward future restoration or revitalization efforts; by drawing taking on account the variety of available graphic sources, this approach allows for a deeper understanding of the historical element, its origins, and its evolution over time [3].

Since the approval of the Ley del Suelo (Land Law) in 1956, Spain has legally recognized “Special Plans” aimed at the “conservation and appreciation of the Nation’s historical and artistic heritage and natural beauty”. Subsequent laws in 2007 and the Consolidated Text of 2008 upheld the same principle of sustainable development (Art. 1.b) and Art. 3, “Principle of sustainable territorial and urban development”. Article 3 of the 2015 Consolidated Text of the Land Law emphasizes the need for public policies to contribute to the protection of cultural heritage, stating that they should “promote the enhancement of urbanized and built heritage with historical or cultural value”.

These measures are supported by international organizations, such as the United Nations, which, through the adoption of the “Declaration on the Conservation of Historic Urban Landscapes” and the “Vienna Memorandum” in 2005 [4], emphasizes the importance of preserving and managing historic urban landscapes as a vital part of cultural heritage. These regulations highlight the need to integrate heritage protection with sustainable urban development, recognizing that historic urban landscapes are not only a legacy of the past but must also adapt to contemporary needs without losing their identity and cultural value.

Among the measures to be taken is the study and graphical recovery of the urban history of sites and geographic areas of significant cultural interest. However, this information is often scattered and difficult to access.

This highlights the need for a centralized database to consolidate various historical documents and maps. Geographic Information Systems (GISs) and their tools emerge as an effective solution for managing this information. Their ability to store data using standardized reference systems, as well as to generate local references for historical cartography, is essential. Moreover, GISs enable efficient information sharing among various stakeholders, facilitating collaboration and data access [5].

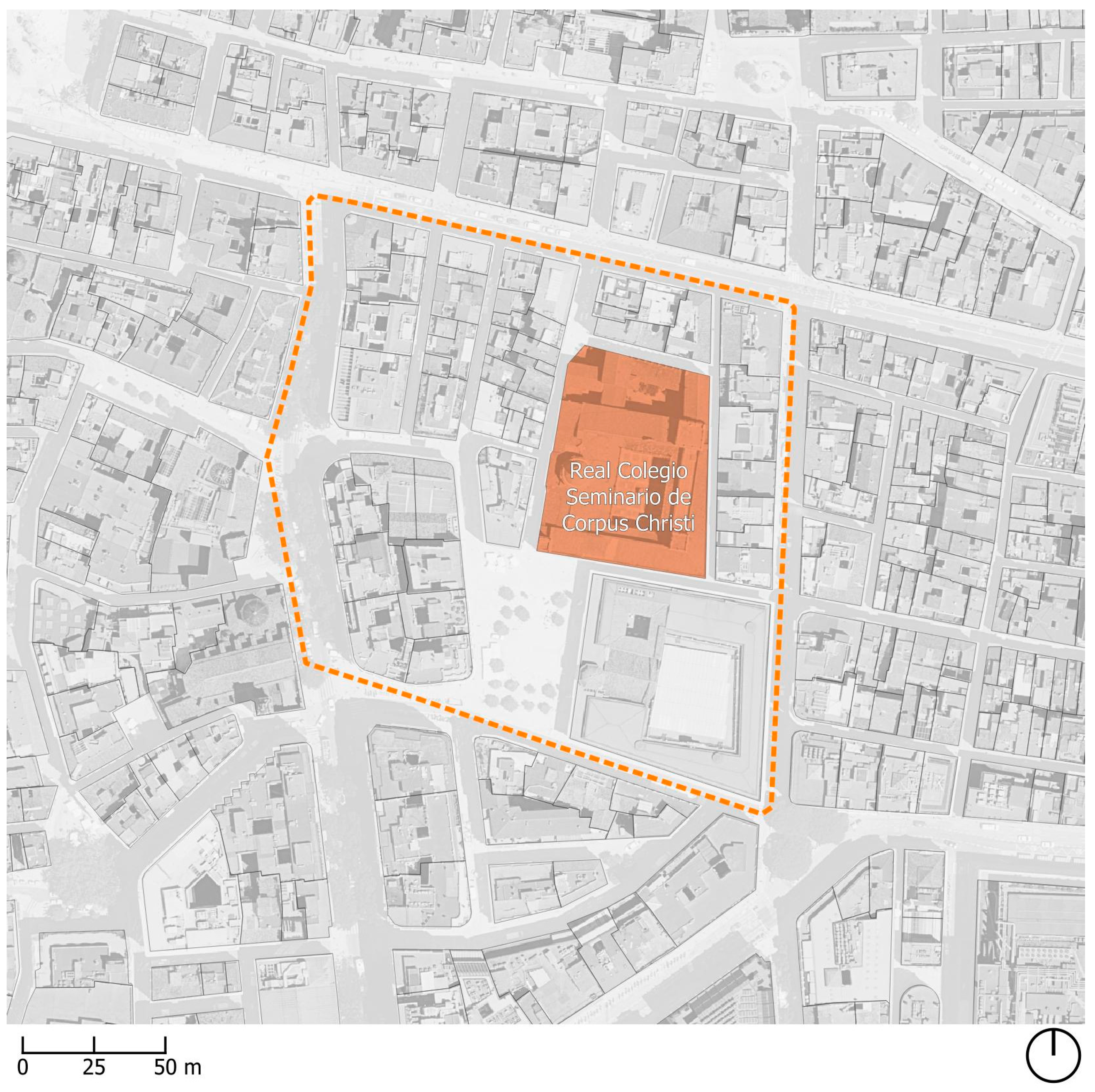

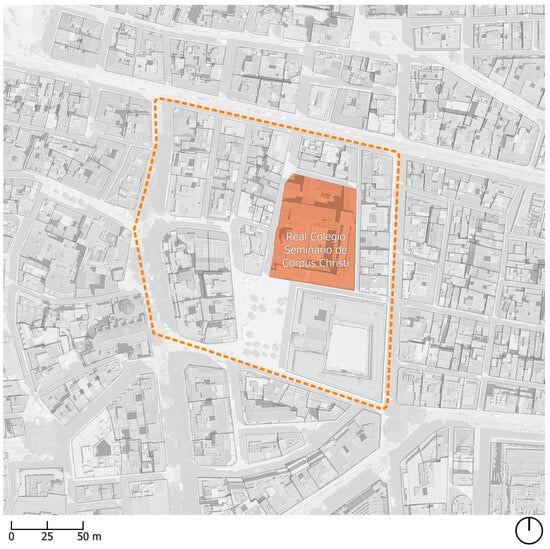

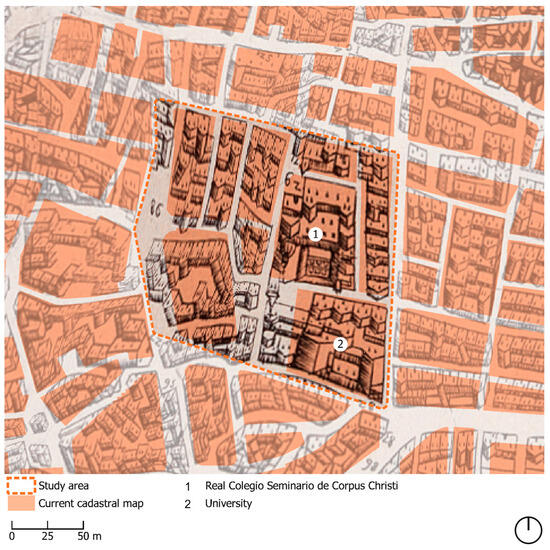

The objective of this research was the graphical recovery of a historical area with significant urban transformations in the city center of Valencia (Spain), specifically the area surrounding the Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi (Figure 1) in the so-called University district, where the spatial structures have been drastically altered numerous times, leaving an indelible mark on the composition and urban landscape.

Figure 1.

Studied area around the Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi.

1.1. Historic Background

The historic center of the city houses the remnants of all the cultures and populations that have succeeded one another over time. Valencia was founded by the Romans in 138 BC [6]. Archaeological findings from this period include the Roman forum and the circus, the latter of which extends into the study area. After the barbarian invasions at the end of the 3rd century, Valencia became an autonomous city governed by bishops. During the Visigothic period, the episcopal complex was constructed (late 5th century) to commemorate the martyrdom of Saint Vincent in 304. It was located to the southeast of the old Roman forum, beneath part of the current cathedral [7]. Although this period is not well-documented, the city experienced a time of prominence as an important pilgrimage center. Significant remnants have not been uncovered in the archeological excavations conducted in the study area.

In 713, Valencia saw the peaceful invasion of Islamic peoples from Africa [8], who named the city Balansiya. This period was marked by prosperity due to the fertile agriculture supported by an efficient irrigation system [9,10], as well as a thriving industry in paper, leather, textiles, ceramics, glass, and metalwork. The city expanded due to the influx of settlers, primarily from Córdoba [11]. In the first half of the 11th century, Valencia was enclosed by a wall built by Abd al-Aziz, which plays a significant role in the study area. Later, in 1238, Valencia was reconquered by the Christian king Jaime I. Initially, the change in population did not bring substantial changes to the city’s urban layout. However, the study area was affected by the establishment of a Jewish quarter, which was entirely walled off [12].

It was during the 14th and 15th centuries that significant urban alterations occurred. This period of prosperity, known as the “Golden Age of Valencia”, is characterized by economic flourishing (fertile agriculture, significant industry, and commercial development) and cultural growth [13]. In this climate of abundance, the city’s cathedral was expanded with the addition of a new bell tower (Miguelete) and a Chapter House where the Holy Grail is currently venerated. This expansion represented a major urban intervention; the urban space was increased, and a new wall was built with access through the Serranos Gate, a recognized symbol of the city. Hygiene concerns led to regulations for street widening, demolition of sheds, and the creation of new streets. The study area, where the Jewish quarter was located, was restructured after the assault on the Jewish community in 1391 [14].

It was in the 15th and 16th centuries that the most drastic urban changes occurred in the studied area, with the construction of two major buildings: the Studi General or University (1493), designed by the renowned architect Pere Compte, who also designed the Lonja de Valencia, and the Real Colegio de Corpus Christi (1586–1615), promoted by the Archbishop and Viceroy of Valencia, Patriarch of Antioch, Juan de Ribera. It was not until the 20th century that another major intervention took place in the analyzed area with the opening of the current Poeta Querol street and the disappearance of squares and streets, which destroyed the character and idiosyncrasies of the neighborhood [15].

1.2. Scientific Literature on the Study Area

The Roman city was analyzed through archeological findings by the archaeologists Ribera and Jimenez [16], who revealed the layout of the circus and the boundaries of the wall. Ribera [7] also examined the remnants of the Visigothic city, detailing the major transformations between the Roman layout and the Visigothic urban form, and provided plans of what the episcopal complex might have looked like, along with an infographic reconstruction of the Visigoth city of Valencia.

Research on the Islamic period and the city’s conquest by Jaime I in the mid-13th century that considers aspects such as urbanism and toponymics is less extensive. One of the first scholars to analyze the urban layout of the medina of Balansiya was Chabás in 1889 [17], who created two inventories related to geographical data and Muslim toponyms appearing in the Llibre del Repartiment. Carboneres [18] developed a “Nomenclátor of the Gates, Streets, and Squares of Valencia” based on data from the Avecinamiento books, which has been highly useful for subsequent researchers. Rodrigo i Pertegas [19] focused on determining the location of the Jewish quarter as delineated by Jaime I and its later expansions.

Recent research has primarily been centered on archeological and archival evidence. Huici Miranda’s [8] contributions have been crucial in understanding Muslim society, while Sanchis Guarner’s [20] study offers a comprehensive view of Valencia’s urban evolution. Cabanes Pecourt [21] identified workshops in the commercial area around Rabat Alcadi (near the Church of Santa Catalina) and examined the neighborhood given to the people of Zaragoza [22] (around the current Plaza de la Reina), based on the Llibre del Repartiment. After them, López [12] mapped the Jewish quarter and its later expansions using data from this document [14].

Following the Christian reconquest, Hinojosa Montalvo [13] conducted extensive archival research that significantly contributed to the understanding of this period. Specific urban areas, such as the parish of San Esteban, were studied by Máñez [23].

The major urban changes in the modern era, notably the construction of the Studi General or University in 1493, were examined by Teixidor and Boira [24]. However, the profound urban transformation associated with the construction of the Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi has been less thoroughly investigated, with significant details provided only in Lerma’s doctoral thesis on the acquisition of construction parcels [25]. Finally, López and Taberner [15] analyzed the near-total transformation of the urban environment in the 20th century, based on historical cartography and urban plans from the Municipal Historical Archive.

While various studies have explored the historical urbanism of the study area, fewer have provided graphical representations of these data on current city maps. There remain significant gaps in the planimetric representation of the substantial urban evolution that has occurred over the years in the area surrounding the Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi in the University district.

Thus, the objective of this research is to enhance the understanding of the urban structures that have shaped the historic center of Valencia over time. This will be achieved through the graphical representation of these structures on current city maps, specifically focusing on the area around the Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi (El Patriarca).

2. Materials and Methods

For this research, three sources of information have been utilized: (1) analysis of historical cartography; (2) review of archeological reports; (3) examination of data extracted from archives.

2.1. Analysis of Historical Cartography

For this research, the Mancelli map (1608) has been used, as it is the oldest map of the city. It was published in 1992 by Fernando Benito Domènech [26]. Later, Pablo Cisneros Álvarez [27] analyzed it in his doctoral thesis. Although this map does not provide reliable information on the geometry or metrics of urban pathways, it offers invaluable details about the streets and squares that existed at the time of its creation. It has been particularly useful for this study because it was produced around the same time as the completion of the Patriarca building. It can be observed that several streets in the studied area have been modified. For instance, the current Plaza del Patriarca was much smaller in the past. The University building had not yet been constructed. The now-demolished Church of the Cruz Nueva was characterized by its bell gable. Additionally, the current streets of La Paz and Poeta Querol have obliterated part of the medieval layout through two major sventramento interventions that significantly altered the original configuration of the area (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Studied area overlaid with the Mancelli map.

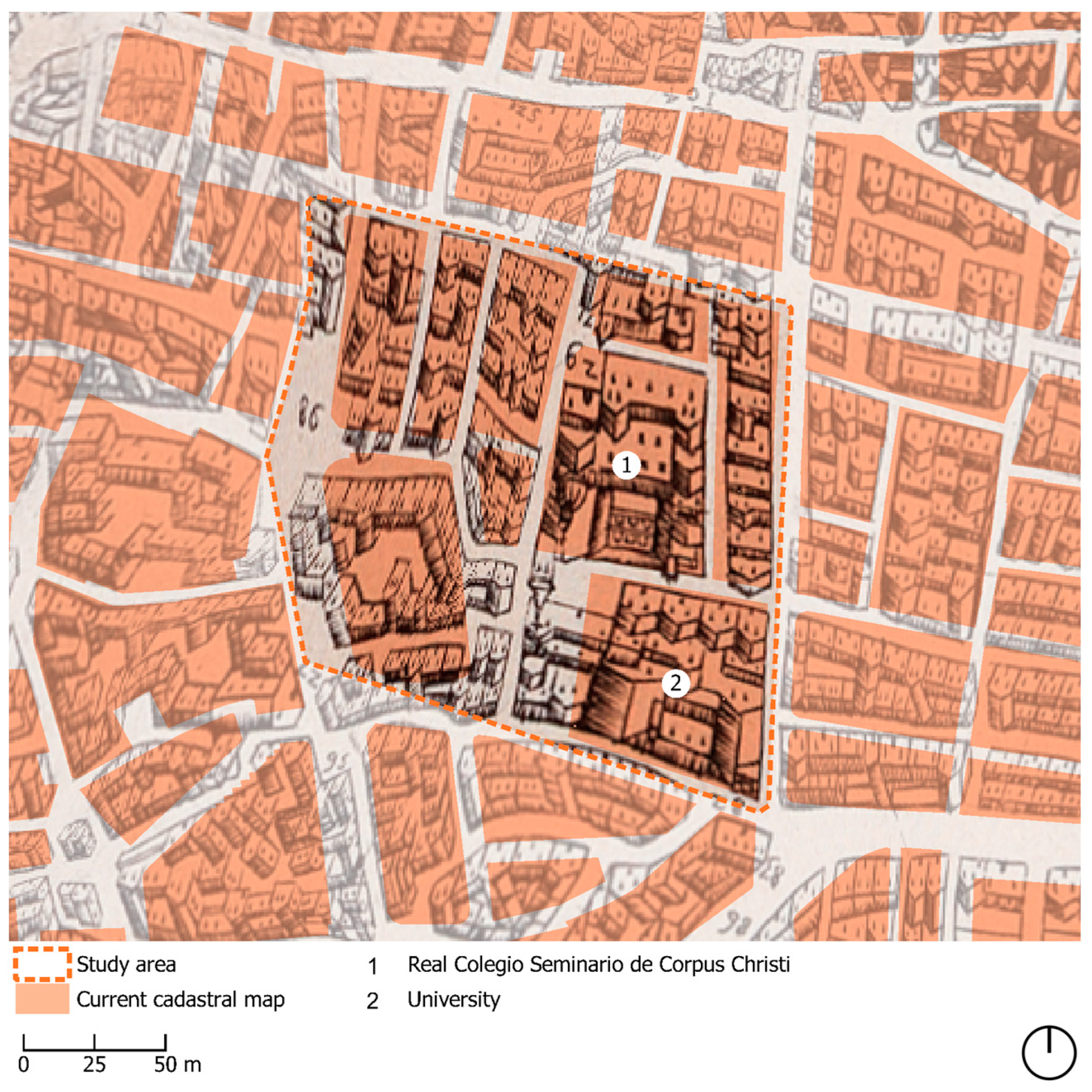

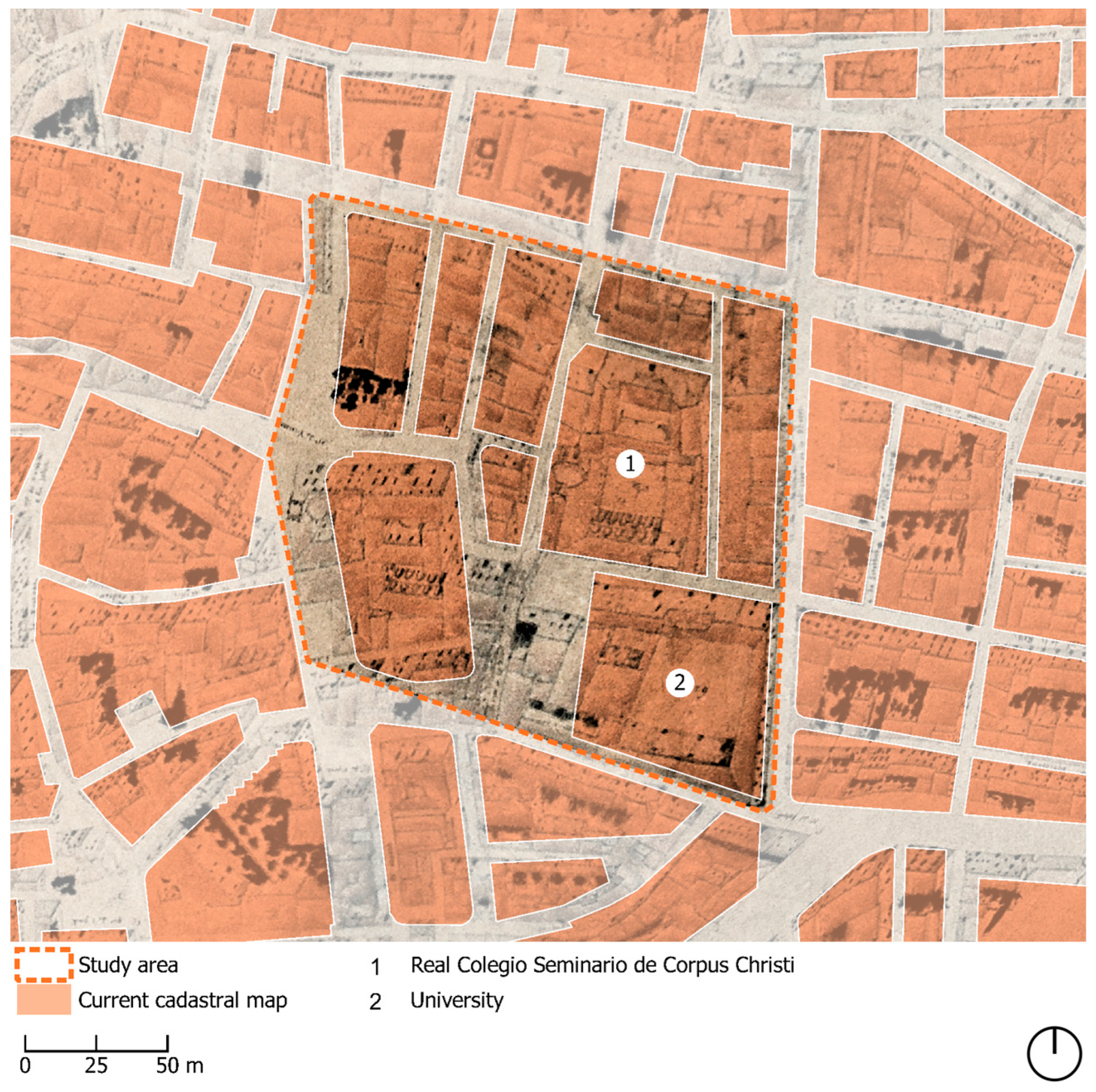

A century later, Father Tosca, in 1704, created a highly accurate map, notable for its measurement accuracy compared to the current cadaster and its representation of significant buildings. This map has been thoroughly analyzed by Gavara et al. [28] (Figure 3). In 1738, Fortea produced an engraving of Tosca’s map, incorporating the urban changes that had occurred since 1704. This engraving has been studied by Taberner and Diez [29] (Figure 4). Both maps have been crucial for this study as they provide insights into the city’s layout in the 18th century. They have been overlaid on current city maps to examine the urban changes that have taken place.

Figure 3.

Studied area overlaid with the Father Tosca map with color correction.

Figure 4.

Studied area overlaid with the Fortea map.

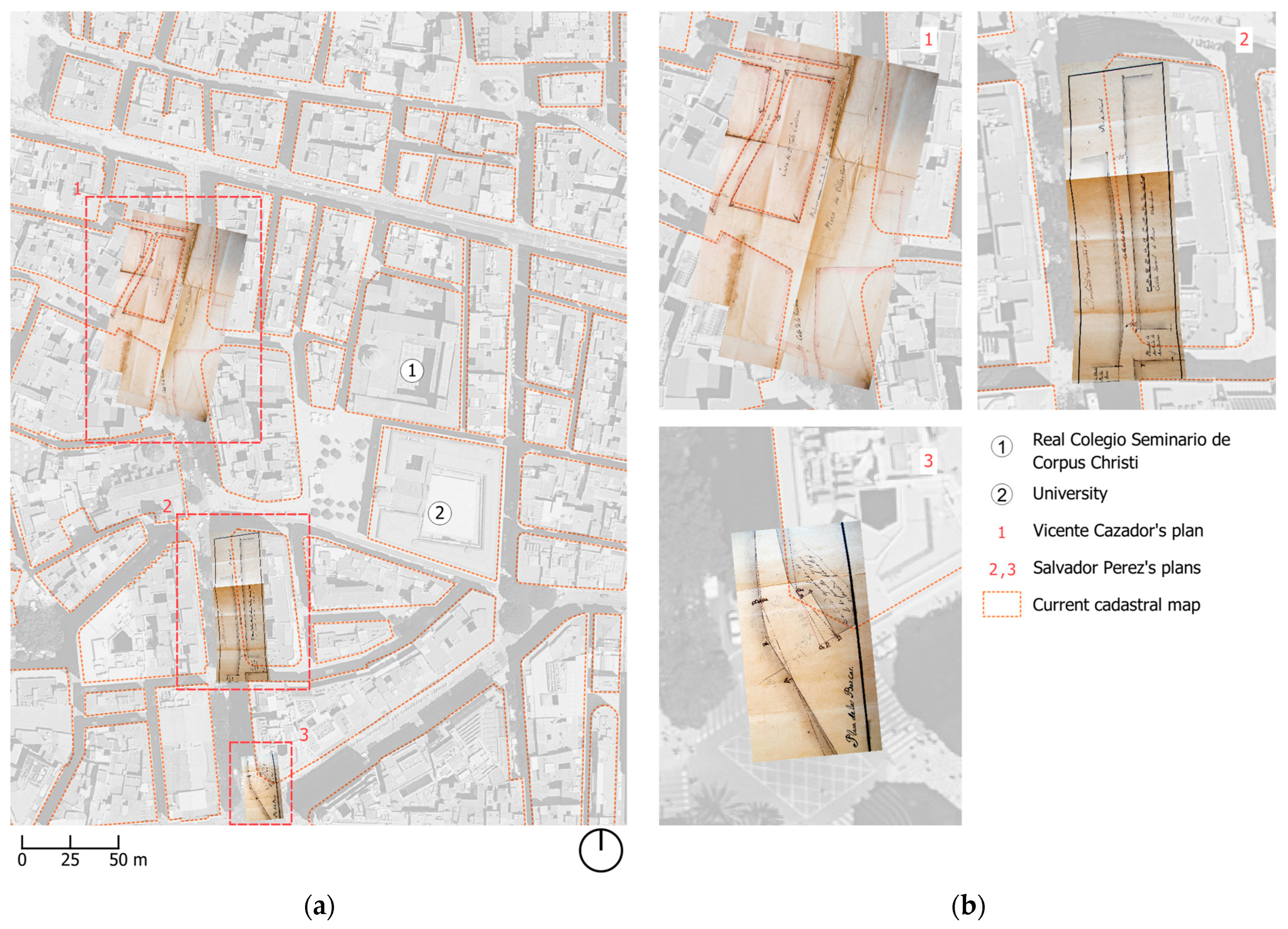

Between Fortea’s engraving and the 19th century, various proposals were made to improve the urban environment in the study area, although most were not implemented until the late 19th century. Notable among these proposals are the following:

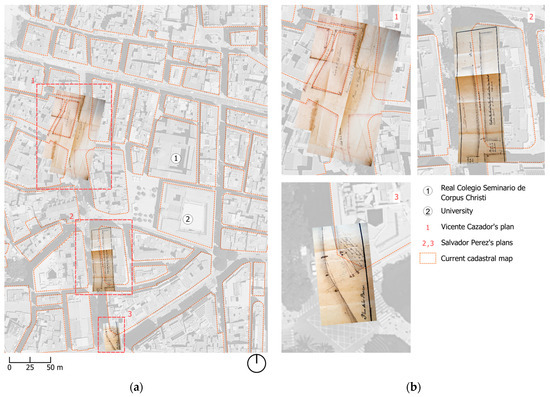

- Salvador Pérez’s map, titled “Rectification and Widening of Calle de las Granotas” (1795), reflects an intention to improve the layout of the now-disappeared Calle de las Granotas by removing bends and angles. This street was located at the current intersection of Calle de Poeta Querol and Calle de Colón (Figure 5) (Archivo Histórico Municipal de Valencia. Rieta ER 1–11 G leg. 8).

Figure 5. (a) Salvador Pérez’s and Vicente Cazador’s plans over the current layout; (b) detailed views of the plans.

Figure 5. (a) Salvador Pérez’s and Vicente Cazador’s plans over the current layout; (b) detailed views of the plans. - In 1814, Vicente Cazador prepared a plan for the regularization of Calle Cardona (Figure 5) (AHMV F. Rieta Legajo 65C), which was included in the broader plan presented by Vicente Belda in 1830.

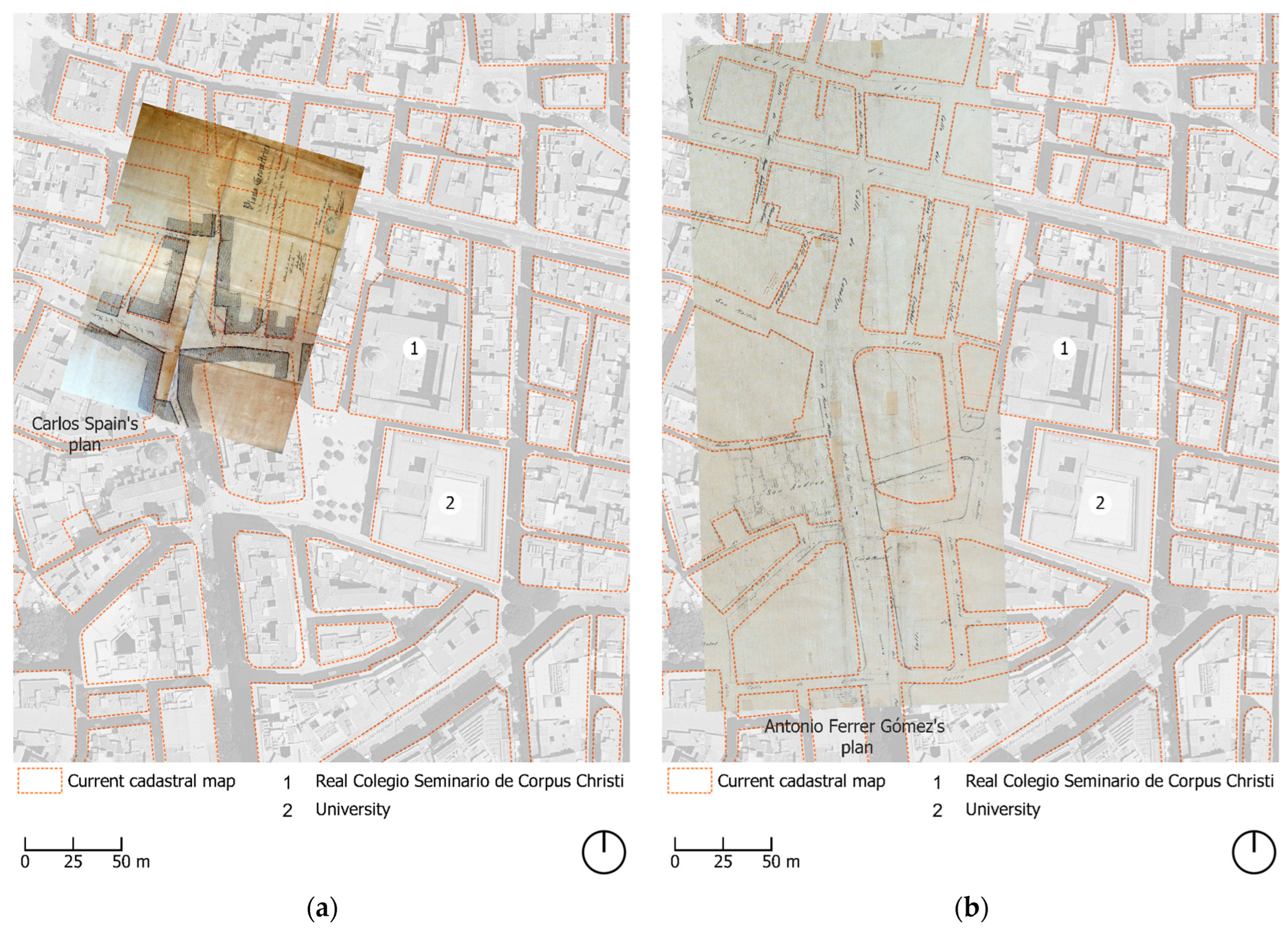

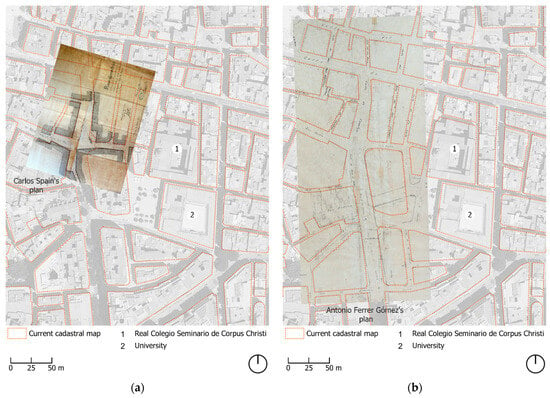

- In 1862, Carlos Spain produced the “Geometric Plan for the Alignment of Plaza de Villarrasa and its Avenues, Prepared According to the Latest Regulations from the Ministry of the Interior” (Figure 6a) (AHMV F. Rieta ERB 11).

Figure 6. Historical cartography over current layout. (a) Carlos Spain’s plan; (b) Antonio Ferrer Gómez’s plan.

Figure 6. Historical cartography over current layout. (a) Carlos Spain’s plan; (b) Antonio Ferrer Gómez’s plan. - The most significant plan from this period is the “Geometric Plan of Valencia” by Antonio Ferrer Gómez in 1892. This plan was crucial for various urban reform proposals up to the mid-20th century. It is highly detailed and accurate, illustrating the layouts of major religious and civil buildings in the city. The plan is divided into 14 sections at a scale of 1/300, providing a high level of detail. The study area is included in Section 9 [30] (Figure 6b).

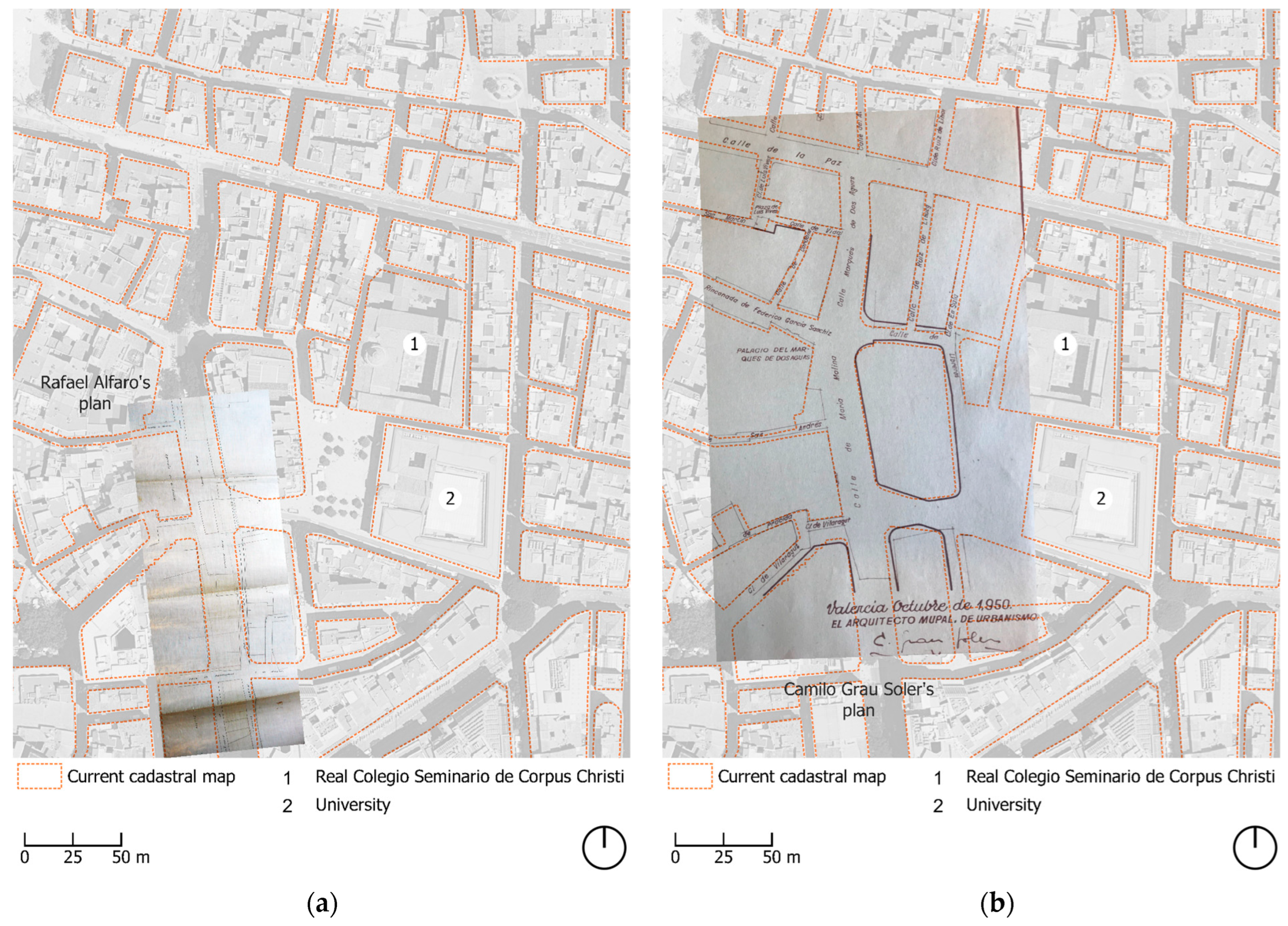

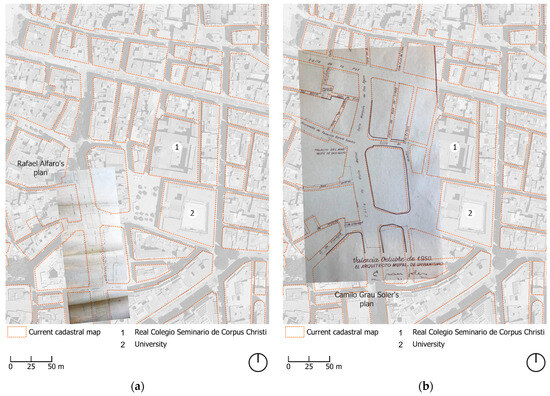

- In 1905 Rafael Alfaro created the most notable plan due to its representation of the drastic urban intervention that would lead to the end of the University district’s urban layout, titled “Project for the Expansion of Plaza de San Andrés and Plaza de Mirasol and the Streets of María de Molina and Poeta Querol” (Figure 7a) (AHMV. F. Rieta Legajo G 1 a 11). Although this proposal was never realized, it served as the basis for Camilo Grau Soler’s 1950 plan, which led to the creation of the current Poeta Querol street (Figure 7b).

Figure 7. Historical cartography over current layout. (a) Rafael Alfaro’s plan; (b) Camilo Grau Soler’s plan.

Figure 7. Historical cartography over current layout. (a) Rafael Alfaro’s plan; (b) Camilo Grau Soler’s plan.

In more recent times, aerial imagery and orthophotos have become available. Among these, historical cartography from the 1956–1957 flight by the Institut Cartogràfic Valencià stands out. This was created using images provided by the Centro Cartográfico y Fotográfico (CECAF) and scanned by the Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Today, Valencia benefits from highly accurate cartography, including various orthophotos and LiDAR scans [31].

To conduct the historical cartography analysis, the historical maps were overlaid with current cartography using the open-source software QGIS 3.38.1-Grenoble. Historical cartography was imported as raster layers; then, the tool “Georeferencer”, which provides different transformation algorithms, was used. For the older maps and plans, which were created using less precise or inaccurate techniques or exhibit greater distortions or deformations compared to modern methods, the Thin Plate Spline (TPS) algorithm was applied. For the remaining maps, the Helbert algorithm was used, as it accommodates the necessary rotations in the absence of a reference grid. In all cases, the Bilinear (2 × 2 kernel) resampling method was employed. After the procedure was completed, a report was generated as output by the mentioned tool with the number of Ground Control Points (GCPs) and the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) (Table 1). Since the TPS technique adjusts maps to the GCPs, the error in fitting these points can be very low because the model is optimized specifically for them. However, this does not guarantee that the fit will be accurate in areas outside these control points. Therefore, Independent Control Points (CPs) that were not included in the initial calculation are used to assess the accuracy of the georeferenced map (Table 2). An expected accuracy given by the scale was considered assuming a graphical error of 2 mm.

Table 1.

Evaluation of the accuracy of the historical cartography georeferencing procedure using GCPs’ RMSE.

Table 2.

Evaluation of the accuracy of the historical cartography georeferencing procedure using CPs’ RMSE.

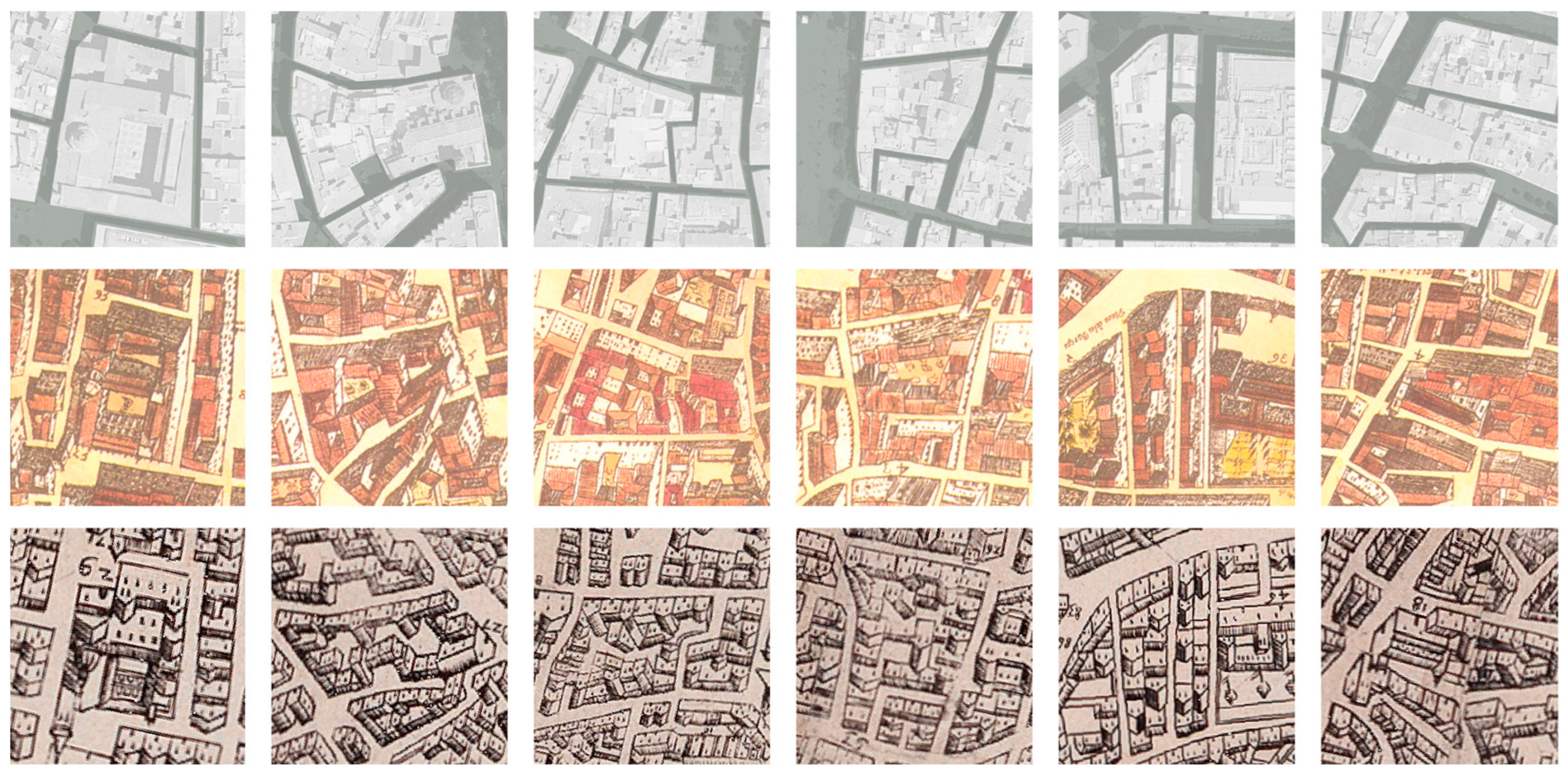

The selection of control points included references to historic urban elements that remain today, such as religious buildings, archeological remains, distinctive urban forms, open spaces, and street axes (Figure 8). Special emphasis was placed on the city walls that define Valencia’s historic center. For the current reference, official orthophotos from the year 2022 with a 0.25 m resolution from the Copernicus Program and the Institut Cartogràfic Valencià [31] were used, along with vector-format cadastral plans of parcels and buildings. All data were aligned using the recommended Coordinate Reference System (CRS) for Valencia, EPSG:25830 based on ETRS89 (European Terrestrial Reference System 1989) and the UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator) projection for the zone 30 N.

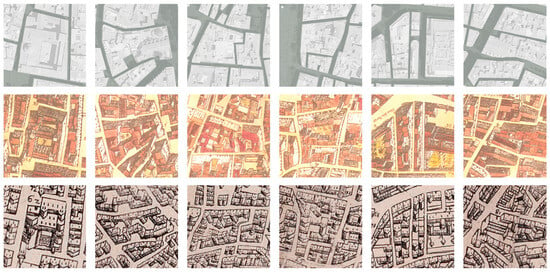

Figure 8.

Examples of homogenous distinctive urban forms in a 2022 orthophoto of Valencia (top), the Fortea map (middle), and the Mancelli map (down).

2.2. Review of Archaeological Reports

Archaeological excavation reports provide crucial insights into the urban development of different historical periods and are essential for any comprehensive study [32]. This section analyzes various archeological reports to georeference the graphical results within the city’s layout, as presented by their respective authors. The technical aspects of these excavations can be found in the respective studies.

2.2.1. Roman Period

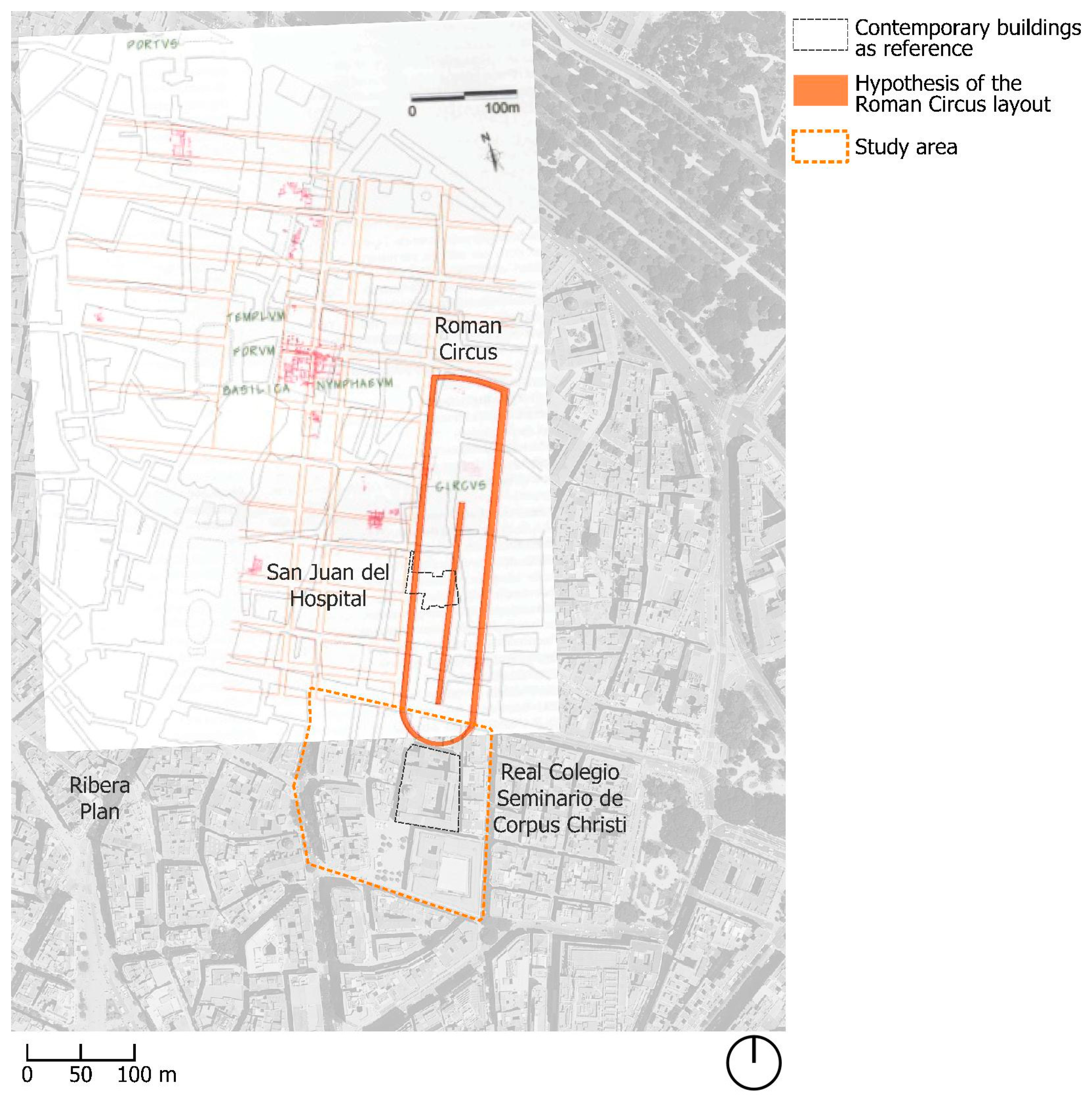

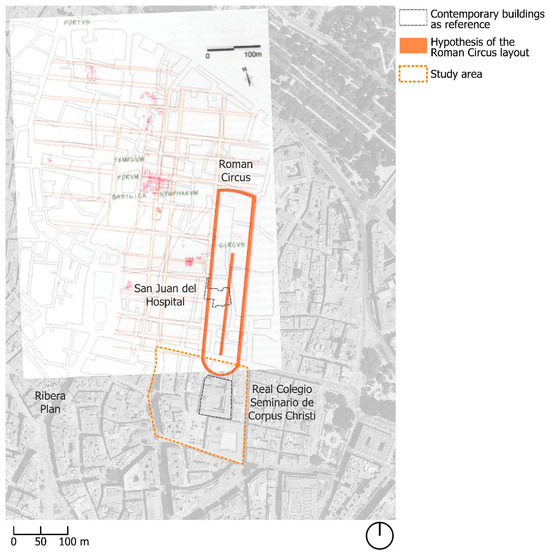

Major excavations of the Roman city of Valentia have been conducted at several key sites by different experts, including the area of l’Almoina, adjacent to the Basilica of the Virgen de los Desamparados and the apse of the Cathedral, as well as at the site of les Corts and Calle Roque Chabás. These excavations have been critical in confirming the city’s founding date [33]. The remains are found at a depth of 4 to 5 m below the current surface level. Although these excavations do not directly impact the study area—since it lay outside the Roman city walls, as evidenced by the discovered remains of the wall—the head of the circus built during the Antonine period, around the mid-2nd century AC, does extend into the study area. The circus was approximately 350 m long and 70 m wide, with a capacity of around 10,000 people [34]. Its location has been confirmed through various archeological investigations [35,36,37] and a hypothetical layout was presented by Ribera [36] (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Roman circus layout based on Ribera [36].

Ribera’s hypothesis aligns with the excavation of the circus’s spina that took place at San Juan del Hospital and the excavations of the circus’ head directed by archaeologists R. Martínez and C. Marín in 1995 (SIAM Archive) between Calle de la Paz and Calle San Juan de Ribera, where two parallel curved walls, approximately 0.50–0.60 m thick, were uncovered. These walls, constructed in opus caementicium, were filled with layers of earth and stones, with external buttresses.

2.2.2. Visigothic Period

There are limited archeological remains from the Visigothic period, with the notable exception of those found at the episcopal complex near the current cathedral. In the study area, it has been documented that the Roman circus remained in use until the mid-5th century. After this period, sedimentary deposits approximately 30 cm thick containing terrestrial fauna remains and carbonized roots indicate a cessation of the maintenance of the sand and, consequently, its functions [38].

2.2.3. Islamic Period

The study area is notably affected by the wall that enclosed the Islamic city. Most of the archeological information comes from reports stored at the SIAM Archive (Servei d’Investigacions Arqueològiques Municipals) under the Valencia City Council and the Archive of the Direcció General de Patrimoni of the Conselleria de Cultura, Educació i Esports of the Generalitat Valenciana. Preceding studies and press releases related to ongoing excavations have also been utilized. A summary of the most relevant archeological reports concerning excavations in the study area is as follows:

Excavation at the Universitat Building (La Nau Building) was conducted by archeologists J. Burriel and I. García (1996–1998) (SIAM Archive). A section of a wall parallel to the building’s facade and a square tower were uncovered. The wall section, oriented N–S, measured 4 m in length, with a preserved height of about 1.50 m and a thickness of 2.50 m. The construction technique used was rammed earth with lime mortar and stones. Additionally, a later construction was documented, consisting of a very hard layer of lime mortar, 0.90 m thick, attached to the tower and the wall as reinforcement.

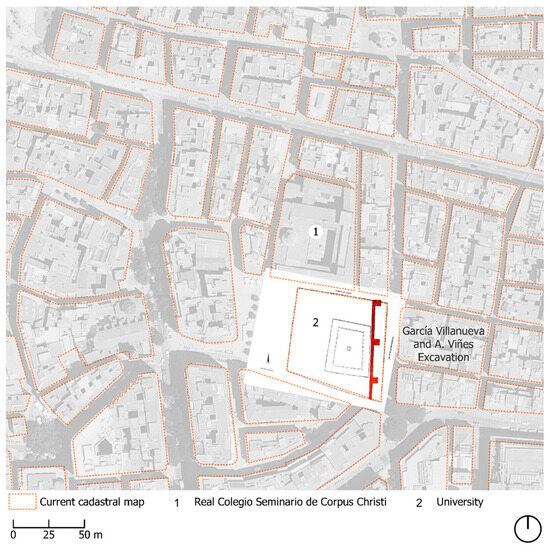

Excavation at the Universitat Building was conducted by archeologists García Villanueva and A. Viñes (1999) (SIAM Archive). A wall section 62 m long and 1.90 m thick dating to the 12th century was uncovered. Inside the building (within the city walls), an Islamic structure from the early 13th century and four 12th-century houses were documented. No earlier structures were found, suggesting that this part of the city was not inhabited before the 12th century (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Valencia walls based on García Villanueva’s and A. Viñes’s excavation (SIAM Archive).

Excavation on Calle Comedias-Mar was conducted by archeologist A. Badía (1991–1992) and uncovered fragments of the Roman circus and Islamic wall (SIAM Archive). A wall segment of the Antonine Roman wall, 8 m long and 5.30 m thick, was uncovered. Externally, at a distance of 2.5 m, a “V”-shaped ditch, 3.8 m wide and 1 m deep, was documented. An adjacent Islamic wall from the 12th century was also found [39].

Excavation on Calle Poeta Querol, in front of the Church of Santa Cruz (San Andrés) was conducted by archeologist Tina Herreros. Islamic baths and the San Andrés cemetery (SIAM Archive) were uncovered [40].

The process to georeferenced the plans in Figure 9 and Figure 10 was similar to the one described in the previous subsection, and the details can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Evaluation of the accuracy of the excavation plans’ georeferencing procedure using GCPs’ RMSE. An expected accuracy given by the scale was considered assuming a graphical error of 2 mm.

2.3. Analysis of Archival Data

Data on urban changes in the city were sourced from several archives: the Archivo de la Corona de Aragón (ACA), the Archivo Municipal de Valencia (AMV), the Archivo de Protocolos del Real Colegio de Corpus Christi (APRCC), the Archivo del Reino de Valencia (ARV), and the Sotsobreria de Murs e Valls (SMV).

There are no contemporary texts describing the Roman and Visigothic cities. However, a document of invaluable significance for understanding the urbanism of the Islamic city of Valencia, Balansiya, is “El Llibre del Repartiment”. This document records all the donations of houses and lands made by King Jaime I to new Christian settlers after the conquest. It includes the name of the Muslim owner, the new Christian owner, the neighborhood where the house was located, and often the Muslim name of the street and its proximity to other properties. The Llibre consists of three Registers:

- Register I contains donations made between 1237 and 1238.

- Register II lists donations made outside the city and thus was not used in this research.

- Register III includes an inventory of houses grouped by neighborhoods, referring to the new Christian districts into which the city was divided, known as “partidas”. Each partida was allocated to a group of settlers from the same region. The study area corresponds to the neighborhood or partida of the men from Tarragona.

López [41] has analyzed the Muslim urbanism of the partida of the men from Tarragona using data from the Llibre del Repartiment, and this research was considered to identify neighborhoods and streets of the Muslim city.

Another valuable document for this research is the “Libro de Compras” of the Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi. In the Archivo del Real Colegio de Corpus Christi, the original book from 1600, titled “Libro de Compras de casas encorporadas en el Collegio y Seminario fundado por el Illustrisimo señor Don Juan de Ribera, Patriarca y Arcobispo de Valencia”, is preserved. A copy made in 1892 by an anonymous author, referred to as “Libro de Construcción y Fábrica”, was used for this study. This document details all the land purchases, specifying the name of the previous owner, the street where each house was located, and its proximity to neighboring properties.

Using the obtained data, a table that omits the purchase date and the owner’s occupation was created, reflecting only the information pertinent to this research: the owner’s name, the address of the property, and the boundaries with neighboring properties. This table has facilitated the analysis of spatial interconnections. Additionally, this document has enabled the identification of streets within the square where the Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi is built now, including Plaza Cabrerots, Buydar les Campanes Street, Cristians Novells Street, Argentería Street, Alguaziría Street, Plaza de la Cruz Nueva, Plaza de Vicente Saranyo, Plaza del Studio, and others [42] (Table S1). An extract of this table can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Extract of Table S1: register of properties for the identification of streets on the current site of Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi found on the “Libro de Compras”.

Using the reference addresses and boundaries data from Table S1 as reference locations, the urban layout of the study area was graphically reconstructed onto the Mancelli (1608) and Tosca (1704) maps, which are the oldest maps of the city. These reconstructed results were integrated into a GIS platform, georeferencing them over the current city maps.

3. Results and Discussion

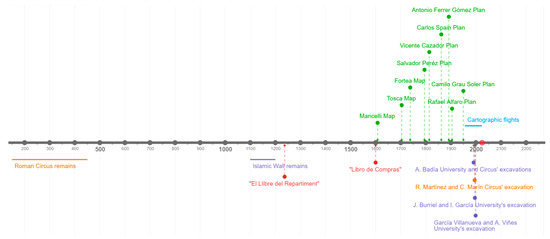

The analyzed data were integrated into the current city map as a palimpsest of various historical maps (Figure 11), revealing the evolution of the study area from the Roman period to the present day. By overlaying these layers and comparing the graphical information with the previously mentioned documentary data, it was possible to graphically reconstruct streets, enclosures, urban ensembles, and elements such as the city walls.

Figure 11.

Timeline with the analyzed documents and historical maps used for the present analysis.

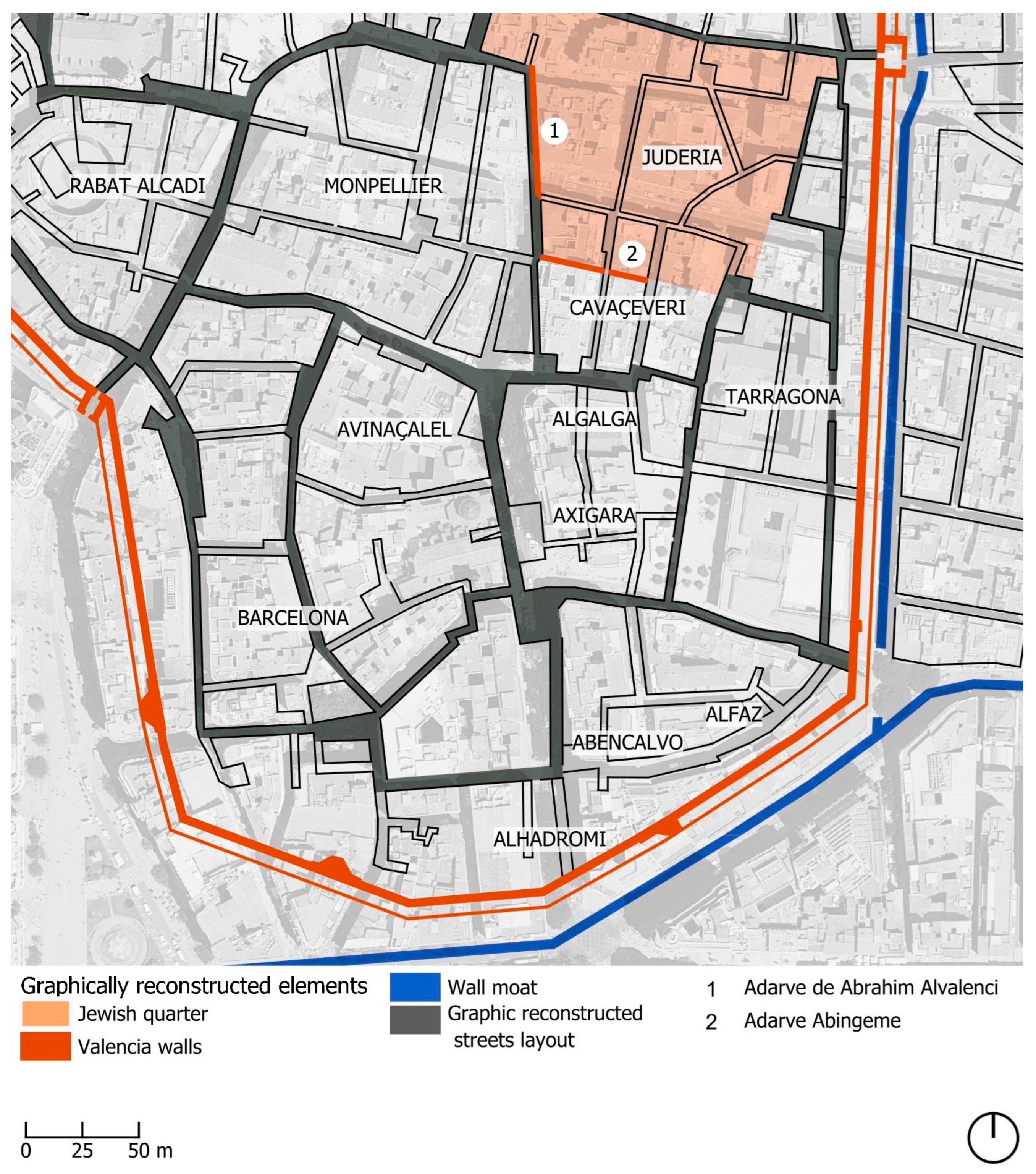

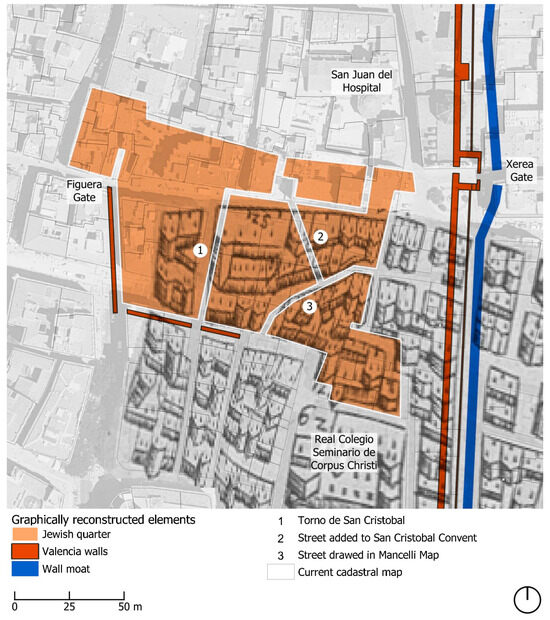

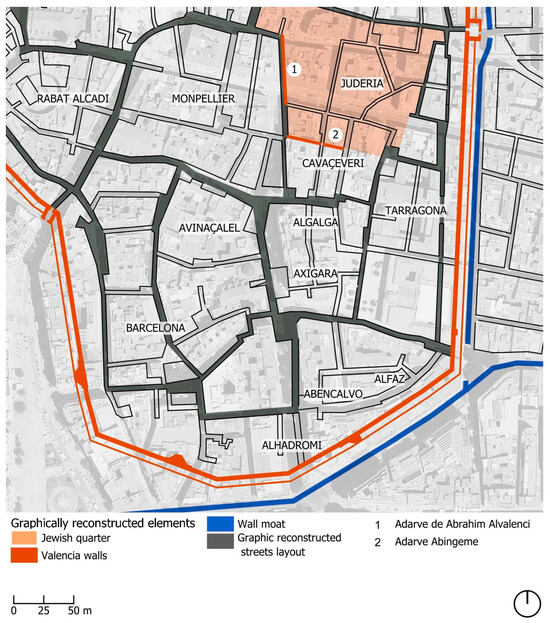

As shown in Figure 12, the layout of streets in the former Jewish quarter, based on data extracted from the Llibre del Repartiment [12,14], was compared with the Mancelli map and archival data.

Figure 12.

Graphical reconstruction of the Jewish quarter based on the Mancelli map overlaid on Valencia’s aerial orthophoto 2022CVAL.

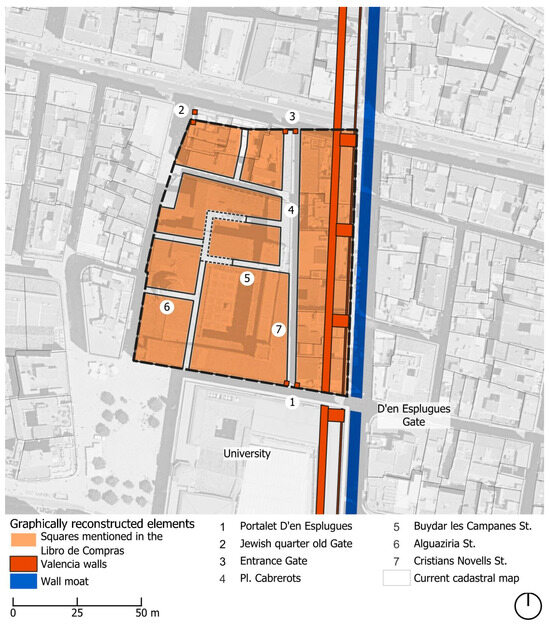

Similarly, a hypothesis was established regarding the organization of spatial structures and the names of certain streets that existed on the site currently occupied by the Colegio del Patriarca, based on the records from the “Libro de Compras” [42] analyzed in Table 1 (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Graphical reconstruction of the urban layout on the current site of Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi, overlaid on Valencia’s aerial orthophoto 2022CVAL.

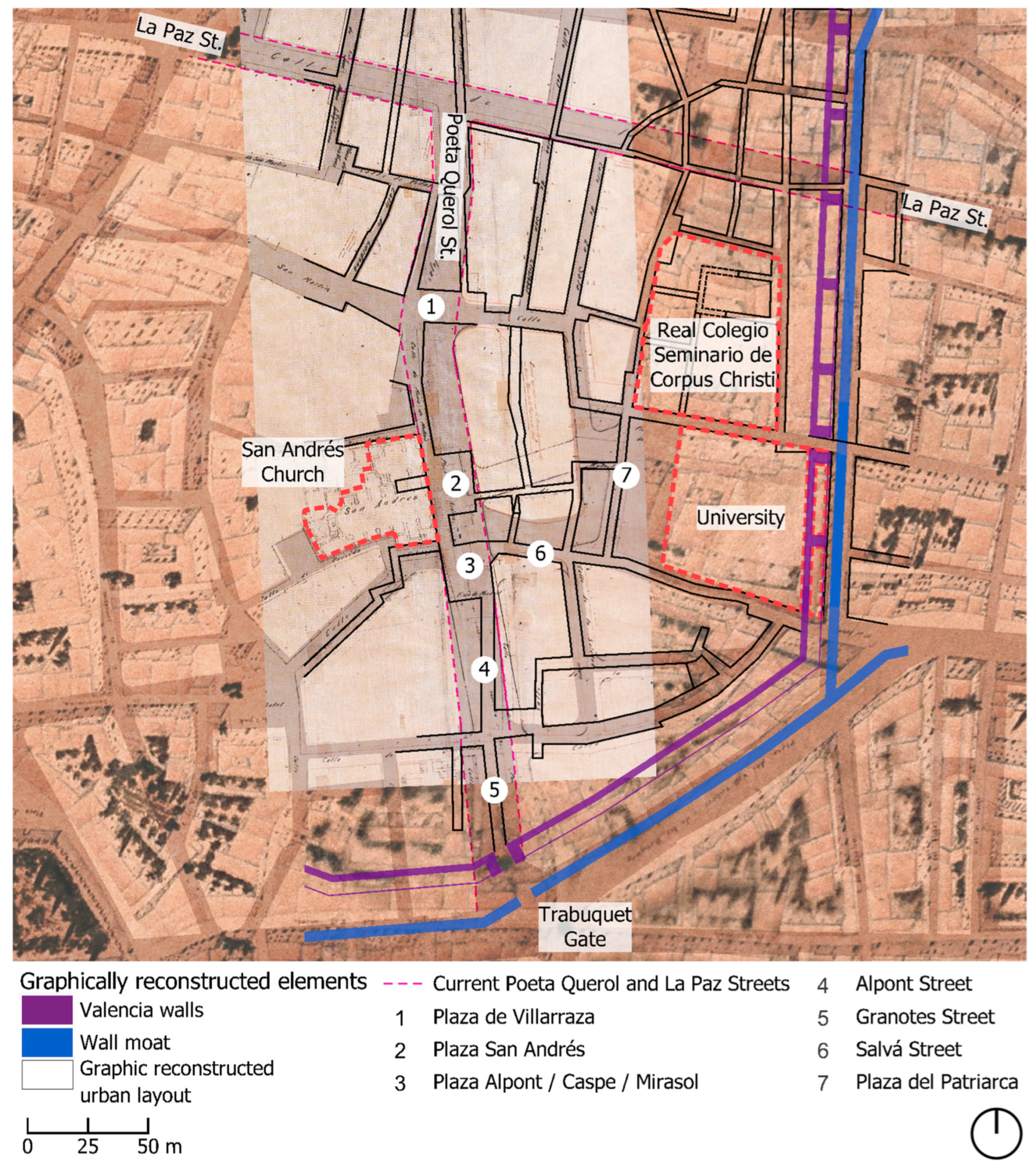

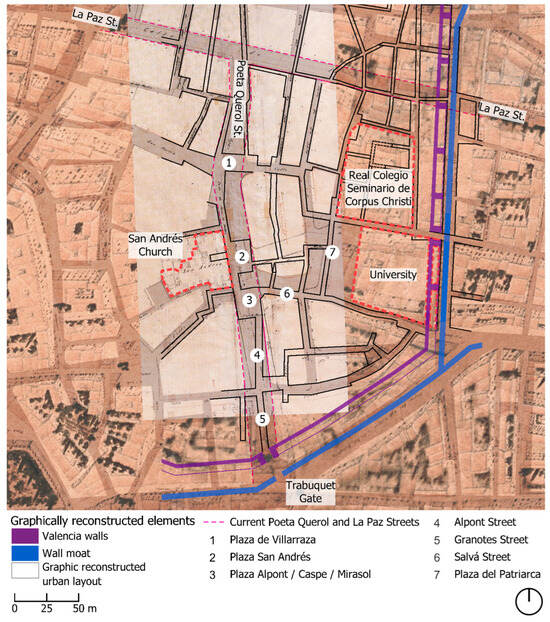

In the same way, we were able to delineate the blocks based on Father Tosca’s plans, showing how the system of open spaces from the old urban fabric has become part of Poeta Querol Street in the present day (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Graphical reconstruction of Poeta Querol Street’s adjacent urban layout based on Antonio Ferrer Gómez’s plan and the Father Tosca map.

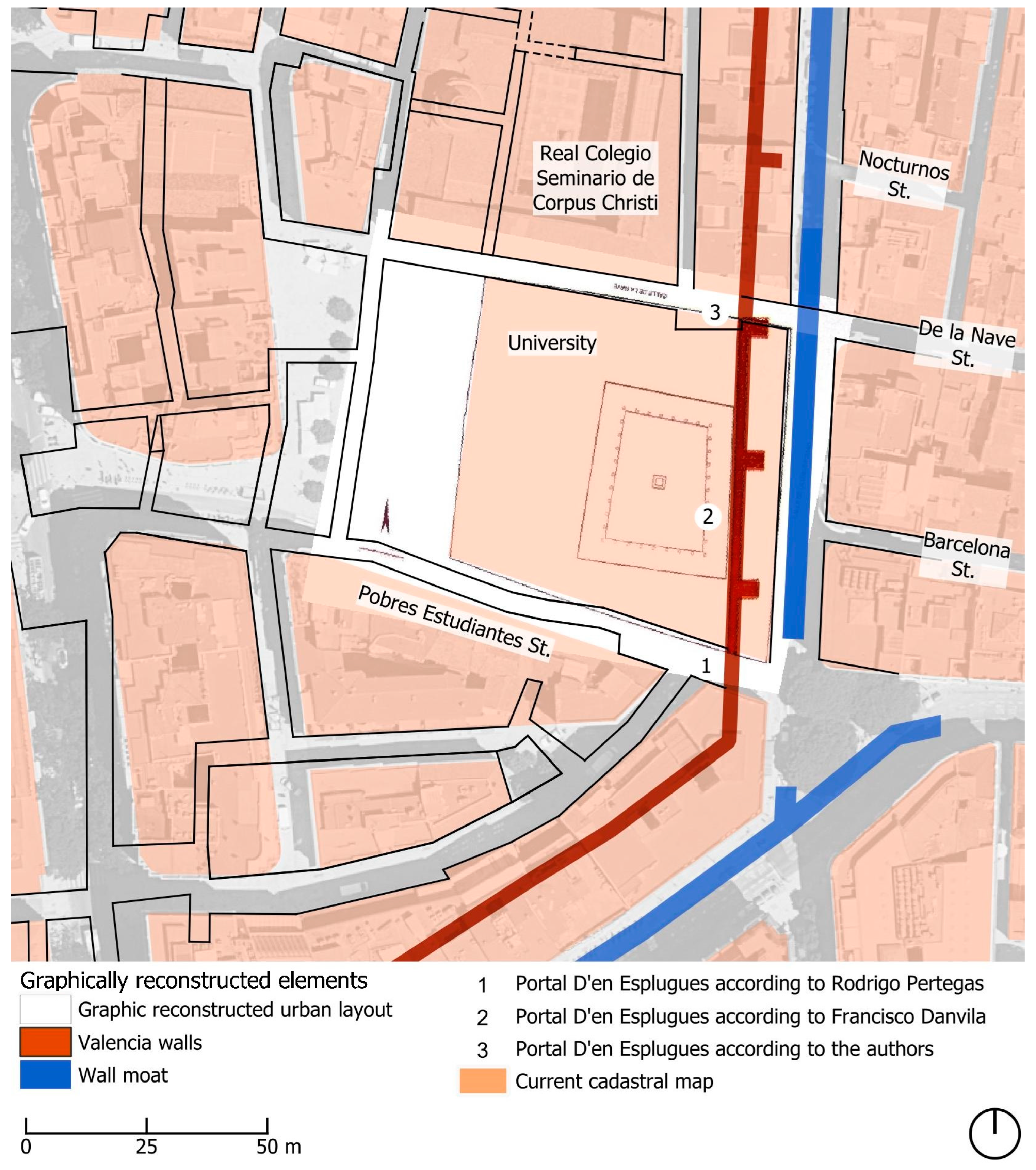

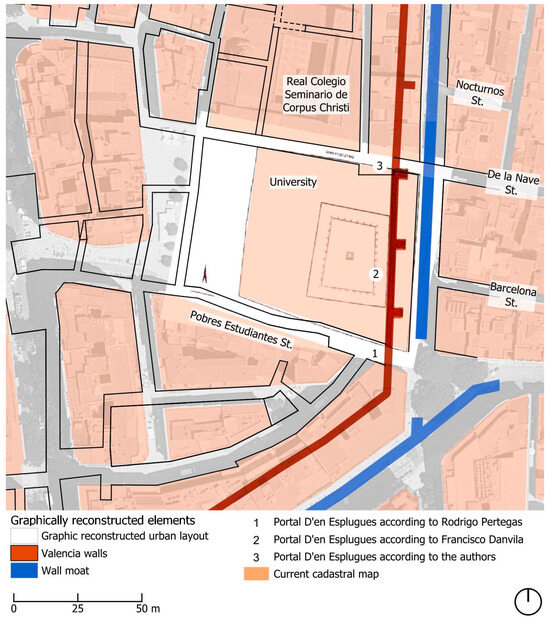

Likewise, it is also possible to gauge the location of the former city entrances through the walls, taking into account the excavations, records, and the plan by García Villanueva and A. Viñes from the SIAM Archive (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Graphical reconstruction of Valencia wall and the Portal D’en Esplugues overlaid on García Villanueva’s and A. Viñes’s plan and Valencia’s aerial orthophoto 2022CVAL.

Finally, it is not only possible to generate graphical information based on all this documentation but also to obtain the toponymy of neighborhoods and streets. This is illustrated in Figure 16, where the names of the sectors of Muslim Valencia have been mapped.

Figure 16.

Graphical reconstruction of Muslim Valencia’s urban layout overlaid on Valencia’s aerial orthophoto 2022CVAL.

4. Conclusions

The dispersion of urban data in a historical geographic area, shaped by various modifications introduced by different cultures and their evolving needs, results in a fragmented visualization of the city’s development. The continuous thread of urban evolution becomes segmented into disconnected pieces. By mapping this diverse information—drawn from written property records, historical maps, and archeological excavations—Valencia’s historical urban layout has been reconstructed and integrated into a unified platform. This integration allows for meaningful comparisons and overlays with existing cartography, offering valuable insights for a deeper understanding of the city’s evolution. In this context, Geographic Information Systems (GISs) prove to be ideal tools for consolidating and managing all information related to the historical urbanism of a city core.

This exercise presented challenges in overlaying maps and creating a palimpsest for a historical area in Valencia. For example, older maps, such as those by Mancelli, Tosca, and Fortea, were created with an artistic approach, using false perspective, less precise techniques than those available today, and the measurement units of their time. While urban forms remain recognizable and many religious buildings have been preserved with minimal alteration, these maps do not easily align with the current urban layout due to their inherent imprecision. Another issue encountered is the current condition of the maps, which are housed in historical archives; often, high-quality scans are not available, and only photographs are accessible, which lack the necessary standards for more accurate georeferencing. These problems are evident in the errors encountered using QGIS’s “Georeferencer” tool, where the expected accuracy was difficult to achieve.

As a result, maps like those by Mancelli and Father Tosca display greater distortion when overlaid with modern cartography. Nonetheless, it has been observed that these maps can be more effectively adapted by analyzing them in segments and correcting their orientation. Open spaces and street axes that conform with singular urban shapes still appreciable today were also taken into account, as these features often provide more consistent references than individual buildings. For this reason, this work does not aim for exact cartographic accuracy, as historical maps lacked the accuracy demanded by modern standards due to the limitations of their time and their expressive nature. Despite the overall lower accuracy of this approach, it can be considered a valuable tool for the graphical reconstruction of historical urban layouts.

Even if the primary objective of this study was to achieve the graphic reconstruction of a historical area in Valencia and its integration into a GIS platform, the georeferencing of historical maps has yielded significant results of notable value. Future research will focus on the development of a GIS database to enable the visualization and sharing of these maps, fostering wider access and promoting further urban heritage studies.

Finally, this study serves as a first step for recognizing and preserving historical traces within this particular area of the city, facilitating future urban interventions and the revalorization of heritage urban elements and hidden streetscapes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage7100262/s1, Table S1: Register of properties for the identification of streets on the current site of Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi found in the “Libro de Compras”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.G.; methodology, C.L.G. and P.R.O.C.; software, P.R.O.C. and C.R.L.; validation, C.L.G. and P.R.O.C.; formal analysis, C.L.G. and P.R.O.C.; investigation, C.L.G.; resources, C.L.G. and P.R.O.C.; data curation, C.L.G., P.R.O.C. and C.R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.G.; writing—review and editing, C.L.G. and P.R.O.C.; visualization, P.R.O.C. and C.R.L.; supervision, C.L.G.; project administration, C.L.G.; funding acquisition, C.L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “Analysis and Development of HBIM Integration into GIS for Creating a Cultural Heritage Tourism Planning Protocol” (ref. PID2020-119088RB-I00), funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation, Government of Spain, and the “Programa de Ayudas de Investigación y Desarrollo (PAID-01-22)” by the Universitat Politècnica de València.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chías Navarro, P. La representación de la ciudad, el territorio y el paisaje en la revista EGA, Mapas, planos y dibujos. EGA Expresión Gráfica Arquit. 2018, 23, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M.; Heath, T.; Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. Urban Spaces-Public Places: The Dimensions of Urban Design, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2003; ISBN 0 7506 36327. [Google Scholar]

- Sender Contell, M.; Giménez Ribera, M.; Perelló Roso, R. Importancia Del Dibujo En Los Proyectos de Rehabilitación. Aceitera de Marxalenes. EGE-Expresión Gráfica Edif. 2020, 28, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Aprobación de La Declaración Sobre La Conservación de Los Paisajes Urbanos Históricos; UNESCO: París, France, 2005; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000141303_spa (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Tamborrino, R.; Rinaudo, F. Digital Urban History as an Interpretation Key of Cities’ Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 2015 Digital Heritage, Granada, Spain, 28 September–2 October 2015; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ribera i Lacomba, A. La Fundació de València; Institució Alfons el Magnànim-Centre Valencià d’Estudis i d’Investigació: València, Spain, 1998; ISBN 978-84-7822-236-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ribera i Lacomba, A. La ciudad de Valencia durante el período visigodo. In Zona Arqueológica; Recópolis y la Ciudad en la Época Visigoda; Olmo Enciso, L., Ed.; Museo Arqueológico Regional: Valencia, Spain, 2008; pp. 302–320. ISSN 1579-7384. [Google Scholar]

- Huici Miranda, A. Historia Musulmana de Valencia y su Región, 3rd ed.; Ayuntamiento de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- López Gómez, A. El origen de los riegos valencianos. Cuad. Geogr. 1974, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Torró, J. Terrasses irrigades a les muntanyes valencianes: Les transformacions de la colonització cristiana. Afers Fulls Recer. Pensam. 2005, 20, 301–356. [Google Scholar]

- Guichard, P. Al-Andalus Frente a la Conquista Cristiana. Los Musulmanes de Valencia (Siglos XI–XIII); Biblioteca Nueva: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- López González, C. Nuevas aportaciones al estudio del recinto de la judería de Valencia delimitado por Jaime I en 1244. Sefarad 2014, 74, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hinojosa Montalvo, J. Una Ciutat Gran i Populosa. Toponimia y Urbanismo en la Valencia Medieval; Ayuntamiento de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2014; Volume I & II. [Google Scholar]

- López González, C.; Máñez Téstor, S. Revisión y nuevas contribuciones al límite meridional y oriental de la segunda judería de Valencia y fijación de los límites de la tercera y última judería: 1390–1392–1492. Sefarad 2020, 80, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López González, M.C.; Taberner Pastor, F. Evolution of the urban image of the University of Valencia district seen through historical cartography and architectural drawings. DisegnareCon 2019, 22, 14.1–14.18. [Google Scholar]

- Ribera i Lacomba, A.; Jiménez Salvado, J.L. La arquitectura y las transformaciones urbanas del centro de Valencia durante los primeros mil años de la ciudad. In Historia de la Ciudad. III. Arquitectura y Transformación Urbana de la Ciudad de Valencia; Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de la Comunidad Valenciana, Colegio Territorial de Arquitectos de Valencia (CTAV), Universidad de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chabás y Llorens, R. El libro del Repartimento de la ciudad y Reino de Valencia. El Arch. Rev. De Cienc. Históricas. 1889, III, 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Carboneres, M. Nomenclátor de las Puertas, Calles y Plazas de Valencia; Imprenta del Avisador Valenciano: Valencia, Spain, 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo i Pertegas, J. La Judería Valenciana; Hijos de Francisco Vives y Mora: Valencia, Spain, 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis Guarner, M. La Ciudad de Valencia; Generalitat Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanes Pecourt, M.D. Los primeros establecimientos comerciales de la Valencia cristiana: Los obradores (siglo XIII). In El Món Urbà a la Corona d’Aragó del 1137 als Decrets de Nova Planta; Claramunt Rodriguez, S., Ed.; XVII Congreso de Historia de la Corona de Aragón: Barcelona, Spain; Universidad de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanes Pecourt, M.D. El barrio de Zaragoza y los zaragozanos en la repoblación valenciana. In Aragón en la Edad Media XXII; University of Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2011; pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Máñez Téstor, S. La parroquia de San Esteban de Valencia y el Palacio del Marqués de Caro: Una Historia Paralela. Propuestas e Hipótesis para Una Reconstrucción Urbanística y Arquitectónica 1238–1519. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixidor de Otto, M.J.; Boira i Maiques, J.V. L’entorn urbà de la Universitat de València. In Sapientia Aedificavit; Universidad de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 1999; pp. 157–177. ISBN 84-370-4163-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lerma Elvira, C. Análisis Arquitectónico y Constructivo del Real Colegio de Corpus Christi de Valencia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito Domènech, F. Un plano axonométrico de Valencia diseñado por Manceli en 1608. Ars Longa. Cuadernos de Arte. 1992, 3, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros Álvarez, P. La Imagen Grabada de la Ciudad de Valencia Entre 1499 y 1695. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gavara Prior, J.; Catalá Gorgues, M.A.; Fuster Pellicer, F.; Roselló Verger, V.M.; Taberner Pastor, F.; Vergara Peris, J.V. El Plano de Valencia de Tomás Vicente Tosca (1704); Secretaría Autonómica de Cultura de la Consellería de Cultura, Educación y Deporte de la Generalitat Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Taberner Pastor, F.; Díez Muñoz, J.L. Nuevas aportaciones sobre el grabado de Fortea del Plano de T. V. Tosca. Arch. Arte Valencia. 2017, 98, 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, J.M.; Llopis, A.; Martínez, R.; Perdigón, L.; Taberner, F. Cartografía Histórica de la Ciudad de Valencia. 1704–1910; Ayuntamiento de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Institut Cartogràfic Valencià—ICV. Available online: https://icv.gva.es/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Giannone, L.; Verdiani, G. Digital reconstruction at the service of memory: Messina 1780. EGE Rev. Expresión Gráfica Edif. 2020, 13, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribera i Lacomba, A. La fundación de Valencia y su impacto en el paisaje. In Historia de la Ciudad II. Territorio, Sociedad y Patrimonio; Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de la Comunidad Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 2000; pp. 29–55. [Google Scholar]

- Escrivá, I.; Vioque, J.; Ribera, A. Guía del Centro Arqueológico de l’Almoina; Ajuntament de València: Valencia, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blasco, J. Plaça Nàpols i Sicilia-C/Almirall-Baró de Petrés. València. In Excavacions Arqueològiques de Salvament a la Comunitat Valenciana 1984–1988. Intervencions Urbanes; Generalitat Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 1990; pp. 202–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ribera i Lacomba, A. El circo romano de Valentia (Hispania Tarraconensis). In El Circo en Hispania Romana; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2001; pp. 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, R. Plaça Nàpols i Sicilia nº1. València. In Excavacions Arqueològiques de Salvament a la Comunitat Valenciana 1984–1988. Intervencions Urbanes; Generalitat Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 1990; pp. 199–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ribera, A.; Rosselló, M. La ciudad de Valencia en época visigoda. In Grandes Temas Arqueológicos 2. Los Orígenes del Cristianismo en Valencia y su Entorno; Ajuntament de València: Valencia, Spain, 2000; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, J. Desarrollo urbano de la Valencia islámica (siglo VIII al XIII). In Historia de la Ciudad. Recorrido Histórico por la Arquitectura y el Urbanismo de la Ciudad de Valencia; Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de la Comunidad Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 2000; pp. 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Herreros, T. El espacio para el rito social: Los baños árabes de la calle Poeta Querol. In Historia de la Ciudad. II: Territorio, Sociedad y Patrimonio: Una Visión Arquitectónica de la Historia de la Ciudad de Valencia; Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de la Comunidad Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 2002; pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- López González, M.C. Toponimia de la Valencia musulmana. La ciudad al sur de la puerta de la Xerea. Archivo de Arte Valenciano 2023, 104, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Libro de Construcción y Fábrica; Archivo del Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi: Valencia, Spain, 1892.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).