Abstract

Two essential characteristics of railway implementation are the large spaces of land occupied in the city and the need for workers. In Spain, both reasons and the post-war period led to the construction of many homes for employees throughout the country using different typologies, ensembles, dwelling designs, free spaces, mixed uses, and a relationship with the surrounding city. The present work presents a quantitative and qualitative analysis of these aspects, concluding on their impact on the current configuration of the urban environment of the cities where they are located and the possibility of urban regeneration that these developments offer. It is a housing stock that is 95% in use and that, in some cases, given the city’s growth, occupies privileged current urban positions that have led to its revaluation despite its construction characteristics. The research carried out provides the analysis of the entire country, accounting for and observing the great variety of existing case studies related to different sizes of populations, typologies, and locations (center–periphery), among others. The main conclusions reflect the total absence of urban or architectural approaches in implementing these homes, the lack of quality of the free or community spaces generated between blocks, and the absolute disinterest in the quality of life beyond providing housing for workers close to the workplace. At the antipodes of current approaches to the design of social housing and living conditions, this situation discourages the regeneration of these homes aligned with the objectives of the 2030 Agenda, making their heritage conservation difficult.

1. Introduction

The study of the urban transformations associated with railway operations and the need to build housing for its workers in Spain has aroused a relevant and growing interest derived from the fact that it is a very relevant housing stock still in use concerning the social housing complex built in Spain. It was produced throughout the Spanish territory, covering significant developments and small housing complexes. This diversity has bequeathed us an essential body of information and analysis that helps us know how such a complex and changing system as the railway works, its influence on urban configuration, and the importance of its protection. Our research about railway housing in Spain started in 2018 and covers more than 20,000 homes, more than 90 cities in Spain, and around 260 social housing developments.

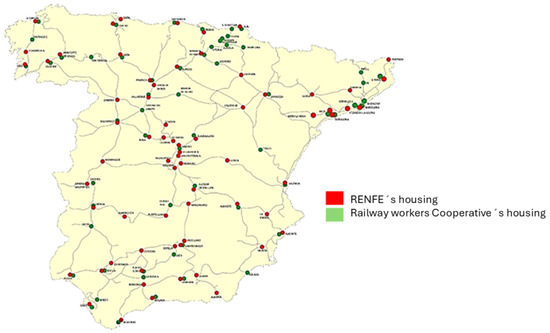

This article focuses on showing three facets related to urban planning and the urban typologies of Spanish cities as part of the unprecedented inventory that we are carrying out on railway social housing, whose study is relevant because it is a vast housing stock spread throughout the country (Figure 1), in towns of all sizes and urban features, being part of the morphological configuration of our cities and, from the heritage point of view, representative of the heritage that most belongs to the citizen: housing. These three facets verify the existence of urban planning approaches in selecting sites and implementing developments, such as infrastructures, urban connection, distance from the center, and the creation of accessible spaces between blocks. There is a need to analyze the typology of blocks and the design of dwellings (cells) for those existing in the surroundings or concerning the configuration of streets or urban environments and the qualitative assessment of these decisions on the housing quality of the dwellings for the inhabitants. Regarding heritage protection, both housing and the city are recognized as elements in primary industrial heritage documents such as the Nizhny Tagil or Krakow Charter [1,2]. However, there needs to be more representation of social housing in Spain on the official lists of heritage protection.

Figure 1.

Location of housing designed and built by RENFE for employee rental and by railway cooperatives in Spain between 1941 and 1975. This is our own elaboration.

Social housing stock is a topical issue and constitutes one of the main objectives of the Sustainable Development Goals, dealing with aspects related to goals 6, 7, and 11. According to the UN, 20% of the world’s population needs adequate housing without essential services such as drinking water or sanitation [3]. Therefore, the existence of specific and applied inventories that contemplate these issues is essential for selecting criteria for the distribution of European aid for rehabilitating the existing housing stock. We have tried to adapt the research as far as possible to the Spanish initiatives about urban sustainability, which are the ones that are summarized here and can be consulted on the website determined by the Spanish Urban Agenda, created in 2019 [4] in line with the 2030 Agenda [5], the new urban agenda of the United Nations, and the Urban Agenda for the European Union. Overall, sustainable urban development, rethinking urban planning and management, and the critical role of cities and settlements reinforce the interest and need for housing research such as the research we present.

The study of railway stations, especially the passenger building, but also other associated facilities such as workshops and warehouses, among others, has explained the stellar role assigned to the passenger building as a reference space in the urban fabric and as a representation of the company that built it [6,7,8]. In this panorama, reference studies have been carried out about the leading railway companies that were established in Spain (Northern et al.) [9,10,11] and that, with the arrival of Franco’s regime, merged to create in 1941 the state railway company called RENFE (National Network of Spanish Railways), which absorbed the old railway companies existing in the country becoming the most critical company (size, employment, and assets) in the country until the 1970s [12,13]. Thus, as a symbol of industrialization and a strategic element in the city, the railway also became an exciting urbanization agent since it had abundant land to be reclassified, making it a critical strategic actor [14,15]. In addition, at the domestic level, the company needed to free up land urgently to provide housing for its workers.

In this sense, between 1945 and the mid-1970s, RENFE developed a plan to build 7000 homes (first, it was 4000, and then it was expanded to 7000 in the 1950s) that aimed to solve the serious problem that affected the railway collective, mainly suffering from this lack of housing, due to the usual transfers and its geographical dispersion. The plan was carried out with notable delays, although it can be considered 80% complete, focused on the main cities and leaving aside medium railway hubs. All these homes were owned by RENFE and were rented to their employees. From 1964 onwards, there began to be a particular change in the promotion of railway housing with the growing presence of workers’ cooperatives that built their homes on their own and where there was no global planning, as in the case of the housing promoted by RENFE.

The presence of the passenger building in the case studies is overwhelming, both as a symbol and as an architectural element, as in Madrid [16], Valladolid [17], Canfranc [18], Bilbao [19], Valencia [20], or Almería [21]. In addition to the passenger building, the whole railway complex also deserves attention [22], which led to the construction of housing for railway employees within these complexes [23,24].

The railway required large spaces and shaped the city as the railway operation expanded with new lines and facilities [25]. In addition to this general overview, we have essential analyses of specific cases such as Madrid [26], Zaragoza [27], Burgos [28], and Barcelona [29]. Attention has also been paid to the railway workshops [30]. In this long and exciting development of railway historiography, a more significant presence of railway housing is missing. Apart from the contributions in the context of the so-called railway settlements [31], finding a global analysis of railway housing in the Spanish case is complex. Only a few local contributions, although equally interesting, exist, such as in Oviedo [32], Valencia [33], or Ciudad Real [34]. In our case, the first approaches to the question have helped us to estimate the importance of its development [35,36]. Various authors have studied the materials and constructive solutions used [37] or the arrival of modern electrical installations and other services in the mid-20th century [38,39]. It is worth delving into the how and where of the construction of these buildings, practically in the 30 years from the early 1940s, with the commissioning of the 4000 RENFE dwellings, until the early 1970s, when the construction of a large part of the railway cooperative housing in the main Spanish cities was completed, as we mentioned above. We have been conducting an exhaustive compilation of the study on railway housing in Spain since 2018 [40]. The size of the study covers more than 20,000 homes distributed throughout the country. Almost 95% of them are still in use (Figure 1). Regarding social housing built in Europe, the research reflects substantial differences concerning the forms of grouping of housing blocks and treatment of public space and their relationship with the city, as well as the composition, material diversity, and construction characteristics [41,42,43,44]. It should be noted that the political and social context in Spain in the period studied (1939–1975) is characterized by material scarcity because of the autarky imposed in the first decades, the rigidity and ambiguity of the few regulations, and the absence of quality control, and this is reflected in the homes analyzed [45].

In railway housing, one of the singularities is the unique link between the working place (railway station) and the living place (railway housing) usually built nearby, which was not always the case from the second half of the 20th century onwards, especially in the social housing built in big cities which forced workers to make long and uncomfortable commuting. This identity of place as a refuge, physical and spiritual [46], helps to see these spaces beyond the simple concept of housing, but as a space to inhabit, a lived space [47]. The concept of human-centered urban design, proposed by forward-thinking urban planners, has significantly impacted how we view and shape our cities. This concept includes ideas like creating pedestrian-friendly public spaces, as seen in Jacobs’ work [48], the importance of legibility, navigability, and imageability in the urban layouts from Lynch [49], and Rossi’s notion of an analogous city with a shared urban memory [50]. These concepts have led to a transformative shift in conceptualizing and building our cities. The research complements the study of contemporary urbanists who have adapted these urban principles to today’s cities. Moreover, this discourse favors innovative and sustainable urban concepts to tackle the complex challenges modern cities face, in alignment with the SDGs and national housing agendas, to create more livable, resilient, and inclusive urban environments. Whereas earlier cities and municipalities were defined by clear territories, the current-day Anthropocene cities have blurred and overlapping boundaries due to phenomena such as urban sprawl. The car-centered city characterized by the linear and perpendicular grid systems is shifting towards a human-centered city with the introduction of proximity-based city models. Driven by the post-pandemic world, widely accepted concepts such as 15-min cities are determined by density, proximity, diversity, and digitalization. Emphasis is given to the integration of nature and urban design. Moreno’s “chrono-urbanism” [51] and Piñeira’s expansion of “soft mobility” [52] both call to rethink the urban transport infrastructure, wherein studies of urban living [53] are equally important. Modern-day urban regeneration focuses on resilience, efficiency, and sustainability by prioritizing pedestrian-friendly spaces, efficient public transportation, and active mobility. Some research results show no uniformity in the forms and spaces of railway housing. Railway social housing is scattered throughout the Spanish territory, configuring peculiar urban landscapes linked numerous times to the railway tracks and stations they serve. These forms, in some cases, are singular urban nuclei and, in others, volumes that stitch together the pre-existing urban fabric. In all cases, the city is configured by clogging or expansion. Our aim here is to analyze whether there was urban planning before the construction of this housing stock that went beyond political interests or real estate profits or whether there was erratic growth from the urban planning point of view without the possibility of understanding logically and rationally the way of urban implantation of these homes. This unpublished work is carried out based on primary sources such as the construction records of the respective housing projects (archive of the Ministry of Public Works and municipal archives) and reports about the land destined for housing construction (Historical Railway Archive). Regarding urban data, public database websites such as SIGNA, SIU (National Systems of Geographical Information), and the Atlas of Spanish Urban Areas are used. This is complemented by secondary sources of academic articles related to urban transformations, social housing, railway infrastructures, and sustainable urban development. Some relevant examples of academic research in this field span urban transformations, social housing, and railway infrastructures [54,55,56,57,58]. The IGN (National System of Geographical Information) photo library, primarily the orthophoto comparison tool, can analyze the changes suffered between the original urban situation and the current one, another essential source analyzed. For the selection of the variables to be studied, we start from the synthesis of the main objectives and application goals established by the New Urban Agenda [5], as well as the analysis of different Spanish urban projects and strategies applying the concept of regenerative urbanism developed by transversal landscape [59].

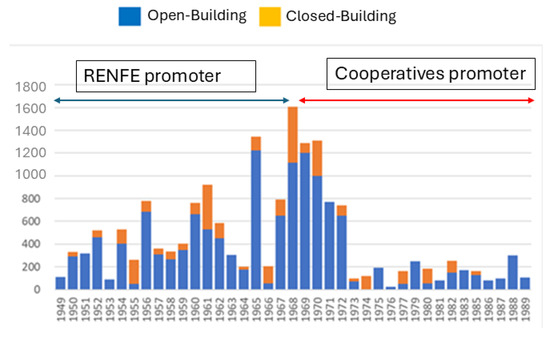

2. Materials and Methods

The object of study is faced from two approaches: on the one hand, via the forms and typologies used to define the geometries of railway housing during the Franco regime; on the other hand, we are interested in the spaces created between blocks and modifying these dwellings in the vicinity of the historic railway space or in the new neighborhoods that widened the growing cities. Lastly, we have conducted a concluding analysis of what we have studied and the influence of these urban decisions on the quality of life for the inhabitants of these minimal and humble dwellings.

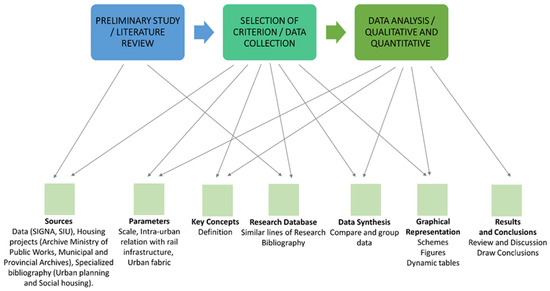

This research is a multi-scale and diachronic analysis concerning the one carried out by the research, which follows a systematic process of studying the different city sizes and their relationship with urban development. The methodology involves the collection and analysis of various data sources. The figure (Figure 2) shows the methodological sequence followed in the analysis. By combining the findings from the literature review, the analysis of the projects and primary sources concerning the inventory of railway housing carried out, and the aerial photos, maps, and statistical data from official sources, this research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the urban transformations associated with railway infrastructures, social housing, and their relationship with sustainable urban development in large, medium, and tiny Spanish cities. Through qualitative and quantitative analysis, the impact of rail infrastructure on social housing and sustainable urban developments, its evolution over time, and its inter-relation with planning strategies for these Spanish cities, can be understood.

Figure 2.

Methodological research model. This is our own elaboration.

The methodology followed includes the quantitative analysis derived from the study of the projects and other primary sources, fieldwork, and the qualitative analysis that aims to assess the urban landscape, surrounding city, urban vitality, and other aspects. Some relevant references are [60,61,62,63,64,65].

This unpublished research is a complex study on railway social housing in Spain that covers the analysis by an interdisciplinary team of housing from various points of view (historical, economic, architectural, and social, among others), where this work presents a part of the analysis of urban parameters carried out. The process followed (Figure 3) after the selection and analysis of sources continues with the selection within each field of study of the most relevant parameters. In this case, a selection of sites in the city, block typology and design of homes, and resulting spaces between blocks have been selected. To this end, the related key concepts and definitions are defined and narrowed down before data collection. The data are compiled into Excel tables, and data mining is performed by handling pivot tables and graphs. For further details of the methodology and material used, please consult our scientific blog COVIFER (see Supplementary Materials).

Figure 3.

Scheme of the methodological research model. This is our own elaboration.

3. Results

3.1. The Design of the Housing Blocks. Forms, Typologies, and Dwellings Design (Cells)

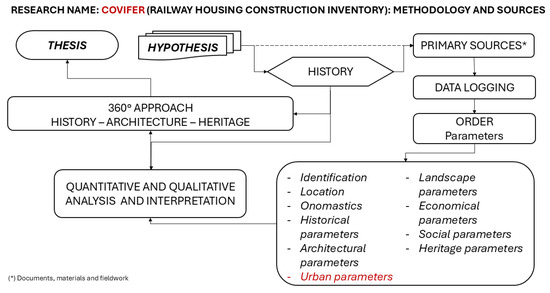

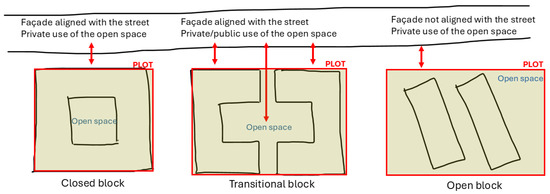

The way of making a city can be simplified in two ways: by clogging up, where, apart from the historical centers where we have not found any interior reform operation for our object of study, the model most used on pre-existing planning is the closed block; and by expansion, with the invention, after the enlargements at the beginning of the 20th century, of the open block in nuclei with a more significant number of inhabitants or through groups of single-family dwellings in less populated nuclei. In both cases, they shared the general trend of building “fragments and fragments within fragments” [66] with a partial vision of the city and, on many occasions, without prior overall planning. In this sense, the construction of the railway housing developments under study follows this pattern with the conditioning factor of being located on plots owned by RENFE, both in the case of the company’s developments and cooperatives and, therefore, the selection of plots depends on the company according to its needs, without taking into account the way the city is built or the preexistent urban fabric. Furthermore, it is necessary to distinguish between the cases of RENFE and the cooperatives since, for the former, the shape, size, and allocation of plots were not regulated. Their construction often took place before the development of any type of planning, while for the latter, the opposite was the case, and this conditioned shape and volume, among other things, as we shall see later on. Another interesting point is that the RENFE developments allow us to observe the evolution from the closed block, passing through the transitional blocks to the open building. At the same time, it is impossible to observe this evolution in the cooperatives because they were built later (since approximately 1965) in more peripheral areas of the cities with a predominance of open buildings. Concerning the period analyzed in both RENFE and cooperative developments, the predominance of the open building typology is evident throughout the period studied (Figure 4).Thus, we can define a closed block as a group of buildings between party walls forming an enclosed polygon with the creation of an interior space occupied in different ways: either as a private open space, as can be seen in Calle Jorge Juan in Albacete (1952) or at Number 308 Avenida Diagonal in Barcelona (1964), both belonging to RENFE; or for commercial use and ground floor premises, as in Calle Marqués de San Esteban in Gijón (1959), belonging to the Langreo Railway Company.

Figure 4.

Urban typology used and leading promoter. This is our own elaboration from analyzed projects.

The coexistence of different uses on the ground floor is a fundamental characteristic of this variant. However, here, we find a generalized use of the ground floor as a dwelling in the cases of closed blocks. This point is essential because the use of the ground floors conditions the urban development of the street and the way of making the city. However, a distinction must be made between the developments built by RENFE, where almost all cases have ground floor housing, and the cooperative developments, where the trend is reversed, with the ground floor used mainly for commercial premises. This evolution responds to a trend that became generalized in the 1960s, perhaps because of greater privacy but also because the rents from the rental or sale of these ground floors helped defray the development costs, as stated in the financial reports of many of these cooperatives. The next step was the creation of transitional blocks where the entire perimeter is not closed, with openings of short length concerning the entire perimeter but maintaining the alignment to the street or plot boundary. Here, we find the cases of RENFE in Málaga (1961) and Villaverde Bajo (1964), and for the cooperatives, the pioneering case of Alboraia Street in Valencia (1954). These examples also show different ways of using the interior public space: the creation of interior streets and landscaped spaces open to the public, although on a different scale to the streets that make up the urban fabric, as in Villaverde Bajo; and the occupation of facilities—the least—(sports courts, commissaries, water tanks, premises, or gardens) for private use (Las Matas); or the creation of a ‘hard courtyard’ without a priori intended use, generally used nowadays for private parking (Alboraia, Valladolid, or Albacete). The case of Villaverde Bajo also illustrates another higher degree of transition towards open building by constructing more housing blocks within the theoretical block. The analysis of these spaces, with the intrinsic complexity of the concept itself, is a subject beyond the scope of this text and, therefore, only an introductory overview. A more significant densification of these blocks is also observed in juxtaposed H blocks, where the case of Málaga would be a clear example (Figure 5). However, the RENFE developments in Aragon, Consejo del Ciento, and the Avenida Diagonal streets in Barcelona clearly show the reduction in the inner courtyard of the block that the use of these H blocks produces. In summary, the much-used double-bay block about 9 m deep is duplicated with the vertical communication nucleus as a nexus without any new housing cell design.

Figure 5.

Aerial view of the 306 housing units of RENFE in Plaza del Fuerte in Málaga. This is our own elaboration from GIS (Spanish National Geographical Information System).

On the other hand, open block is understood as that which is used on the outskirts of cities where, within large plots or superblocks, free-standing blocks of different geometry are arranged freely concerning the plot boundaries, generating open spaces between blocks and where ground floor retail usually disappears in favor of arcades, premises, or housing. This is the formula for building the city most used both by RENFE and by the cooperatives, contemporary with the way of building the city in force in the 1960s and 1970s. However, as we explained earlier, the RENFE developments began to be built at the end of the 1940s. They show the evolution from the closed block to the open building, passing through the transitional block, with clear examples of each stage. The following figure clarifies these concepts (closed, transitional, and open block) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sketch about the typologies used. This is our own elaboration. Regarding the generalized loss of urban vitality when comparing the open building with the traditional closed block, in our case, this would not be the case because most of the developments, both in open buildings and in the closed block, have ground-floor dwellings and used to be located next to the usually remote railway enclaves (Figure 7).

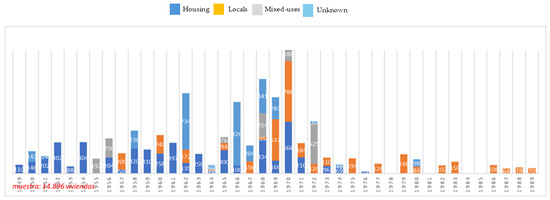

Figure 7.

Use of ground floors without distinguishing between developments built by RENFE and railway cooperatives between 1941 and 1975. This is our own elaboration based on the projects studied. Sample: 14,806 dwellings.

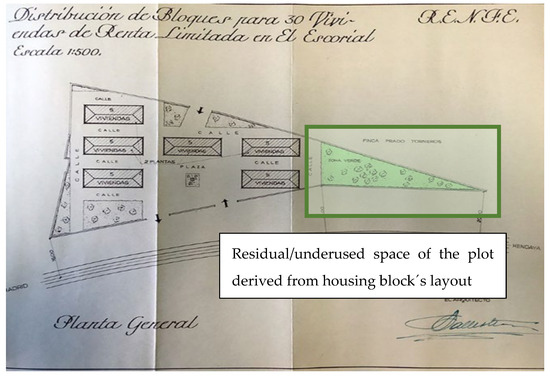

However, the loss of the façade–street relationship does occur due to the adaptation of this way of building the city. In contrast, the theoretical improvement in hygienic conditions derived from this way of building the city would not be such a consequence either, since the pass-through dwelling has been adopted practically since the first developments, both in closed blocks and in open building, with the use of double-bay blocks and construction using load-bearing walls (narrower bay widths suitable for the pass-through dwelling to have the desired surface area of around 60 m2). In contrast, the typological evolution derived from the search for a smaller façade surface area and a more significant number of dwellings served by a vertical communication nucleus for more significant economic savings will practically eliminate the pass-through dwelling and, therefore, those theoretical health benefits it entails. In the realm of single-family dwelling construction, the most prevalent model is row housing with a backyard. This often involves homes that are attached in the most straightforward configurations, such as in the case of Manzanares (1952) developed by RENFE. Alternatively, homes may be arranged in parallel or perpendicular blocks, or placed adjacent to one another, as seen in the second phase of the ‘Hermandad Católica Ferroviaria’ cooperative in Linares-Baeza (1968). This typology is predominantly found in towns with fewer than 5000 inhabitants. To summarize, row housing is a common architectural style in Spain, particularly in semi-rural areas. This is largely due to the fact that both materials and construction techniques are typically managed by local builders, which reduces costs through the sharing of load-bearing walls. Additionally, the inclusion of a backyard provides residents with a desirable small portion of private garden space. Finally, the detached single-family house of one or two floors is uncommon in our case study, and we have not found any cases. The typological variety is in the open building modality, where we can find the most incredible variety. Although this is a general outline, several variables are very significant: the time frame, both because of the change in trend from the imperative need for housing to speculation and because of the regulatory development both in urban planning—especially in cities with the approval of general plans and therefore of urban planning parameters that condition the shape and volume of the block—and in terms of social housing or construction; the economic situation throughout the period under study with what it entails in terms of access to materials, immigration of workers from rural areas, and execution deadlines; and, finally, the construction of housing by the cooperatives since, as they are independent developers, the projects have no relationship beyond the repetition of typologies well known by the architects adapted to the urban planning regulations of each location. About the urban regulation of cities, the first general plans in Spain were born after the Land Law of 1956. Until then, our homes, especially from RENFE, had hardly any urban planning limitations beyond alignments, block width, and height, about the width of the street in the best cases. The issue of health and the need for housing was the problem to be solved, and this was the focus of the laws applied to cheap houses. Regarding social housing, the Order of 20 May 1969 represents a before and after concerning the design of dwelling cells and, therefore, blocks. Thus, for our case study, the proportion of use of open blocks (80%) compared to closed blocks (20%) in the homes analyzed so far is overwhelming, although the first group (open blocks) also includes the so-called transition blocks detailed above. Analyzing in detail, concerning the first group, the variety concerning the shape of the tablet is the dominant tonic throughout the entire time frame studied, without being able to determine any pattern, although with some considerations. In the first place, the most commonly used typology is buildings made up of isolated rectangular parallelepipeds with passing dwellings (without interior courtyards) that are used continuously throughout the studied years. Behind this trend, we can determine several causes: RENFE projects are very similar; there is a preference for thorough housing to improve hygienic conditions; and the repetition of construction techniques and materials means greater technical, economic, and deadline control [37]. The predominant typology in population centers with less than 5000 inhabitants is row dwellings. At the same time, for large cities, we find all kinds of variants, including some buildings in the open, as in the Barcelona cooperatives in the San Andrés del Palomar neighborhood, or zigzag in the homes of the company Ferrocarriles del Tajuña in the Vicálvaro neighborhood of Madrid. The arrangement of the buildings on the plots does take into account adapting the buildings to the most favorable orientation but not to the quality of the spaces that are generated between blocks (free or community spaces) or with the boundaries of the plot, generating in many cases spaces that, due to their location and their relationship with the accesses, remain residual, as is the case in the 30 RENFE homes in El Escorial, where the right part of the triangle is entirely detached from the homes but is counted as free space (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Location plan of 30 RENFE homes in El Escorial. Source: Public Works Ministry Archive. Signature M-5475-RL.

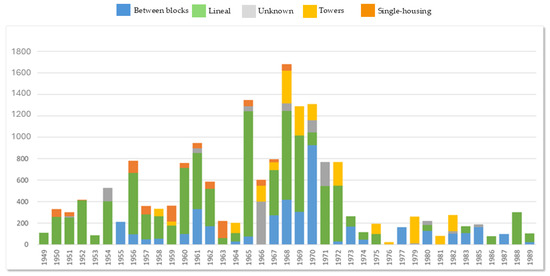

Aside from the dominant orthohedrons, other building typologies have been utilized, such as the comb, as seen in the structures along Avenida de Aragón in Valencia or Plaza de Amézola in Bilbao. These were built by RENFE and the cooperative “Nuestra Señora de los Llanos” in Albacete, showcasing their significant role in shaping the architectural landscape. Similarly, the L-shape, observed in the buildings at the Tarragona station square or the Santander neighborhood of Cajo Sixto by the cooperative “Sagrado Corazón de Jesús y Nuestra Señora de la Bien Aparecida”, adds to the variety, despite these being variants of the rectangular prismatic block. The pure U-shaped block was not built, although it was planned in a project by Alfonso Fungairiño in Ciudad Real, but surely due to the intense activity of the railway cooperative, the RENFE project was not necessary and was cancelled. However, U-shaped blocks were combined with a central I-shaped figure. Undoubtedly, one of the most relevant examples is that of the RENFE development next to Delicias station, where an extension in height was also carried out after the construction of the first phase, as was also carried out in Oviedo. Also, in the case of Castejón (Navarra), we find this form of central U-shaped blocks with central I-shaped figures. Regarding the architects who designed the buildings, there are also apparent differences between RENFE and the cooperative’s developments. RENFE had architects on staff who repeated the projects regardless of the population, while the cooperatives freely and autonomously chose their architects. This characteristic is also reflected at the urban level, with homogeneity and repetition in RENFE developments and heterogeneity and variety in cooperative developments. More evolved typologies such as well-insulated or juxtaposed H-blocks, blades, or the tower as a later typology result from the change in priorities: savings in vertical cores and façade surface, as well as the application of structural systems based on reticular frames. The hygienist or sunlight premises will go to a second step with the elimination, in many cases of through homes and the increasingly common incorporation of courtyards of minimal dimensions (Figure 9). As singularities, we find the Sevilla railway district of Calle Perafán de la Rivera, next to the old railway access of the line from Córdoba to Sevilla, where the L-shaped buildings are combined with some in the shape of a comb, rectangular, or the T-blocks that we only find at the moment, in the Córdoba development of RENFE de San Cayetano.

Figure 9.

Block’s typology. This is our own elaboration from analyzed projects. Sample: 14,890 dwellings.

Regarding the dwelling cell design linked to the choice of typology, we do not observe any project experimentation in the cases studied, despite adapting new typologies, overcoming the period of economic hardship, or the emergence of cooperatives with their respective architects and different projects. In summary, we are dealing with “project automatisms” [66]. In this sense, we do have to make a vital assessment: although RENFE housing offers a specific variety not conceptual in the design of cells to accommodate different types of families, cooperative housing will not present this distinction a priori since all cooperative members are equal, contribute the same, and the homes will try to reflect this equality.

3.2. The Space Between Housing Blocks: Free and Community Spaces

Regarding free spaces, we distinguish between housing and community spaces. Concerning the first, practically 80% of the homes analyzed have a terrace, balcony, gallery, or both, observing a more significant variation in sizes and designs in the homes of the cooperatives as they are autonomous and later projects. If we separate by developer group (RENFE or cooperatives), we can see the predisposition of the latter for these spaces (only 12% of the planned homes do not have some type of open space), while in RENFE, 33% of the homes studied do. About the second group, in cases of open building, apart from the residual nature mentioned above, which has led to a situation of abandonment in several cases, such as Valladolid (Figure 10) or Albacete, generating spaces that do not imply more excellent quality because of their larger surface area or that, when designed open, do not offer a design that provides quality to the public space, other times they are located where there is an essential mass of trees (Aranjuez) or where there is an area of complex topography (El Escorial) but not because they integrate a natural singularity, which would be desirable, but rather to avoid it. In the cases of closed blocks analyzed, it is crucial to note that a considerable number of them (63%) lack free space. This is primarily due to the occupation of this space by ground floor premises. Another significant factor is the increase in the buildable depth, which also contributes to the lack of free space. Additionally, the adoption, by regulation, of courtyards of minimum dimensions further exacerbates this issue.

Figure 10.

View of the state of the open space of the promotion of the cooperative “Virgen Milagrosa” in Valladolid (Spain). This is from our own archive (2022).

These spaces between blocks within the same development, although in many cases they are freely accessible, should be considered for almost exclusive community use by the inhabitants of the development rather than being really public.The configuration and space between the blocks, as well as the homogeneity in the compositional, constructive, and material characteristics used in the dwellings, generate a segregated spatial and urban vision, which also contributes to their isolation in addition to the isolation already generated by the socio-economic characteristics of their inhabitants. López de Lucio’s [66] approaches to the peripheral urban approach align with this circumstance. This reference author proposes a diagnosis of the inhospitable and uprooted construction in the peripheries of Spanish cities, the case study being a clear example of this. Lack of connectivity, absence, or lack of diversity of urban activities, and of basic facilities or equipment, among others, are some characteristics that must also be addressed in the rehabilitation and improvement of the urban sustainability of these housing stocks, mostly in use.

3.3. The Location of Developments

The rail workers’ dwellings were located near the railway stations and other facilities crucial for the operation of the railway, such as workshops and locomotive depots. Any statement to the contrary would be surprising since, on the one hand, with its land, the railway company RENFE could make a new allocation for this use at little cost, and, on the other hand, the proximity to the workplaces continues to be a highly valued advantage, both by companies and by workers. Otherwise, travel costs would negatively penalize the option of new homes. Thus, most of the houses built in the period studied were built on railway land, as we have seen above. Although, at present, within the urban landscape, the spaces are only sometimes identifiable as railways since the environment has been wholly reclassified and the houses have been integrated into the neighborhoods. The homes built by RENFE in the Plaza de Embajadores in Madrid or on the Paseo de la Alameda in Valencia may lead to the mistake of thinking that they were land acquired by companies for this purpose, but this is different. However, they were spaces that already had an old railway use. Thus, in the case of Madrid, it was the transit area of the link line between the Mediodía station (Atocha) and the North station (Príncipe Pío), with a link to the Delicias station, so when the renovations of use in this area began, where the Peñuelas and Paseo Imperial freight stations were also located, the reallocation of use proved relatively easy for the railway company. In Valencia, the Alameda buildings were next to the old station of the Central de Aragón Company, which connected the Levantine capital, through Sagunto, with Teruel and Calatayud, so that, when a large part of the railway services began to be deactivated at this point, the installation of housing was quite logical. Nowadays, both spaces are not easy to identify as being used by rail and are located in an urban area of some prestige. Another example would be that of Sevilla, especially in the neighborhood of San Jerónimo, in the north of the city, which we have also mentioned, the point where the main line arrived, which, through the Guadalquivir Valley, connected Sevilla with Madrid, and where workshops and depots for steam and diesel traction locomotives were also installed. Today, there is hardly any evidence of steam workshop warehouses, semi-abandoned and unused, so the successive housing developments of RENFE and railway cooperatives are not easily assimilated into their railway past. In addition, as in these and other cases, together with the construction of housing for its employees or the transfer of land for the cooperatives, RENFE also agreed with the municipalities to exchange land for other housing developments of the INV or social equipment, integrating everyone into the new neighborhoods created. As happened in San Cristóbal de los Ángeles, in the vicinity of the workshops of Villaverde Bajo, on the other side of the tracks, where the city of Madrid widened, there RENFE built a significant housing development that was to benefit above all the workers of the Central Repair Workshops (TCR) of Villaverde. RENFE also agreed to develop other services, where an agreement was reached with the Madrid City Council to cede land for the construction of other homes and a public school (Figure 11).

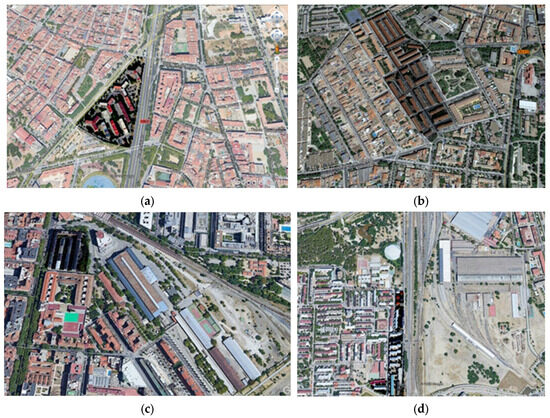

Figure 11.

Location of some housing developments in densely urbanized areas of Barcelona, Ciudad Real, and Madrid. Source: our own elaboration from GIS. (a) Groups of 9 blocks and 659 homes of the San Andrés Arenal cooperatives in Barcelona, next to the old General Workshop of RENFE wagons; (b) groups of 32 blocks and 604 homes of the Ciudad Real cooperative, next to the land of the old MZA station in the city; (c) groups of 248 RENFE homes next to the Delicias station (Madrid) and railway facilities; (d) groups of 15 blocks and 504 homes in San Cristóbal de los Ángeles (Madrid), next to the railway workshops.

In small towns and semi-rural areas, houses were constructed more naturally as a logical extension of the spaces occupied by the railway. In many cases, they gave continuity to other groups of houses built by the old railway companies parallel to the tracks. Among these cases would be Algodor (Madrid), Arroyo-Malpartida (Cáceres), Castejón (Navarra), El Escorial (Madrid), Guadix (Granada), Las Matas (Madrid), Mòra la Nova (Tarragona), Reus (Tarragona), and Venta de Baños (Palencia) (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Examples of housing construction next to railway tracks. (a) Las Matas, Madrid; and (b) Arroyo-Malpartida, Cáceres. This is our own elaboration from GIS.

In other cases, they are new extensions that were no longer located in railway areas in the absence of land suitable for housing construction. This issue was especially the case in large cities, where there were more difficulties in using railway land, such as Madrid and Barcelona, and both in the case of developments carried out by RENFE and by railway cooperatives, although more so in this case, since these cooperatives were more likely to go to the land market offered by the municipalities in the new neighborhoods that were designed. The four blocks of housing built in the expansion of the new neighborhood of Tetuán de las Victorias, the three housing developments in the central sector of Avenida Diagonal in Barcelona, and the construction of those above the unique “fort” of Málaga in the new neighborhood of Carranqueare all examples of RENFE developments. This option of resorting to land in new extensions and extensions in urban growth was more common among railway cooperatives, such as in Sevilla, Valladolid, Valencia, and many others. Therefore, the choice of land was made based on economic criteria and, to a lesser extent, urban planning. However, we also find references to cases, isolated indeed, of selective reference to the land. Thus, in Lleida, the primitive location of the RENFE housing development in 1952, was discarded because it was very close to the municipal cemetery, which in turn was close to the railway freight station, which was the reason for choosing this place. On the opposite side, there was the promotion of homes under construction in Madrid, in the area of Calle Padre Damián and Calle Doctor Fleming, near the Paseo de la Castellana and the Salamanca neighborhood, for other plots that would allow the construction of other social housing developments (Figure 13).

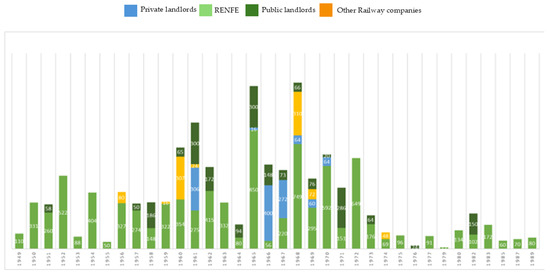

Figure 13.

Property of soil in Spanish railway housing stock. This is our own elaboration from analyzed projects.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The choice of location, shape, and dimensions of the plots of the developments carried out by RENFE was a decision of the company based on its needs and its availability of land where, in no case of those analyzed so far, have we observed arguments of urban nature in the choice of these, beyond the proximity to the workplace. Given that housing is still in use, they constitute urban legacies that must be integrated into cities and in which it is more complicated to apply mobility solutions and urban sustainability or adapt them to the essential urban conditioning factors. Most of the plots of land owned by RENFE and many of the cooperatives were built on undeveloped land, and there needs to be a type of treatment for urban parameters in the projects analyzed. In other words, the creation of the city that these developments contributed to was erratic concerning the characteristics, axes, and foci, among others, of the population where they were implanted. They only share the common trend, especially in RENFE promotions, of making the city grow near railway facilities, often far from consolidated nuclei. This particularity, together with an inefficient design of the open spaces between blocks both in open buildings and in the cases of closed blocks with a central community courtyard, can be seen in the analysis of projects. The space between blocks seems to be understood as a residual space, a factor that significantly contributes to social segregation. No routes are proposed for them, and each type of equipment, such as playgrounds, community centers, or green spaces, is proposed in only some cases. The blocks are often arranged without considering those spaces, which, together with the characteristic of locating homes on the ground floor, are especially detected in RENFE’s promotion more than those promoted by railway workers’ cooperatives. This arrangement leads to ‘social segregation’, where certain groups are isolated or excluded from the broader community, which causes social segregation. The railway cooperatives allocate the ground floors to premises to obtain rents but need an objective of improving community spaces or urban planning to improve the city. This decision facilitates the social segregation of these developments, as observed in the Madrid developments of San Cristóbal de los Ángeles or Villarverde Bajo, despite the growth and urban development of the surrounding city. This matter can reveal the absolute isolation to which the inhabitants of these developments were subjected when they were built, in addition to the constant contact with the workplace for all members of the family, in many cases without any urban equipment (paved access, sewerage, water and electricity from the urban network, or others). If there was any, it was the one that the company decided.

In conclusion, there was no intention of urban or social integration but paternalism and dependence, above all, on the part of RENFE. These characteristics hinder the urban regeneration capacity of these homes in line with the sustainable development goals. At the same time, they show the growing inequality gap that exists in our cities. There are no project singularities worth mentioning regarding the typologies and the design of dwellings (cells’ design). This issue is precisely the interest of the analysis because they are ordinary dwellings still in use and, therefore, represent a reliable source of how housing was made at that time. The files and projects describe the actual situation and the fundamental interests behind the construction of these houses because they were anonymous projects. They thus clearly showed the reasons for the choice of land, the materials used, the techniques, the prices, and budgets, exposing all the casuistry that occurred (difficulty of access to materials, contradictory prices, the ideology behind the design of cells, among others), but in no case were urban planning aspects or the relationship between the individual and the city parameters what mattered. Despite this, the evolution in the development of urban and technical regulations meant an undoubted improvement for the inhabitants of these dwellings. This increase is observable throughout the period analyzed. The social housing analyzed constitutes a relevant heritage in use and requires improvement and adaptation actions to both the new criteria of urban and housing sustainability. With regard to the former, which is the subject of this analysis, functional sustainability actions are necessary, understood as improvement, integration, and diversity of urban activities, improvement of accessibility and basic facilities, elimination of barriers generated by large roads, railway lines, or other features, and revaluation of open spaces. These actions will in turn make it possible to act on social sustainability, that is, to eliminate the social segregation that the very configuration and design of these developments produces in some cases.

Supplementary Materials

All the inventory and information related to the research carried out can be visited on our scientific blog called COVIFER: https://covifer.hypotheses.org/estadisticas-statistics (accessed on 4 November 2024).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.-C. and D.C.; methodology, A.M.-C., D.C. and T.L.D.R.; software, D.C. and T.L.D.R.; validation, A.M.-C., D.C. and T.L.D.R.; formal analysis, T.L.D.R.; investigation, A.M.-C. and D.C.; resources, A.M.-C. and D.C.; data curation, A.M.-C., D.C. and T.L.D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.-C. and D.C.; writing—review and editing, A.M.-C., D.C. and T.L.D.R.; visualization, A.M.-C.; supervision, A.M.-C., D.C. and T.L.D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this research work are not available because this is ongoing research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the archive staff of the Ministry of Public Works, the general archive of the administration, the regional and local archives visited, as well as the staff of the library and archive of the Spanish Railways Foundation for their help in the search and location of the files consulted for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carta de Nizhny Tagil.TICCIH. Carta de Nizhny Tagil. 2003. Available online: http://ticcih.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/NTagilPortuguese.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- S.a., Carta de Cracovia. Principios para la conservación y restauración del patrimonio construido. Astrágalo Cult. Arquit. Ciudad. 2001, 17, 127–134. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2611196.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- ONU-Habitat. Web1. Available online: https://onu-habitat.org/index.php/vivienda-inviable-para-la-mayoria (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Agenda Urbana Española. Web2. Available online: https://www.aue.gob.es/ (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Agenda 2030 Web3: United Nations. New Urban Agenda. 2017. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/about-us/new-urban-agenda (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Bertolini, L. Nodes and places: Complexities of railway station redevelopment. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1996, 4, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinsma, F. The impact of railway station development on urban dynamics: A review of the Amsterdam South Axis project. Built Environ. 2009, 35, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, M.V.; Triggianese, M. The spatial impact of train stations on small and medium-sized European cities and their contemporary urban design challenges. J. Urban Des. 2021, 26, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Civera, I. La Estación de Ferrocarril, Puerta de la Ciudad; Consejería de Cultura, Educación y Ciencia: Valencia, Spain, 1988; Volumes 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- López García, M. MZA: Historia de sus Estaciones; Centro de Investigaciones Sociologicas: Madrid, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrino, J. La arquitectura ferroviaria en Andalucía. Patrimonio ferroviario y líneas de investigación. In 150 años de Ferrocarril en Andalucía: Un balance; Consejería de Obras Públicas y Transportes: Sevilla, Spain, 2008; Volume II, pp. 823–885. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Rubio, M. RENFE, 1941–1991: Medio Siglo de Ferrocarril Público; Ediciones Luna: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Carreras, A.; Tafunell, X. La gran empresa en España (1917–1974). Una primera aproximación. Rev. Hist. Ind. 1993, pp. 127–175. Available online: https://raco.cat/raco/index.php/es/inicio/#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Capel, H. Los “Ferro-Carriles” en la Ciudad Redes Técnicas y Configuración del Espacio Urbano; Fundación de los Ferrocarriles Españoles: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Santos y Ganges, L. Urbanismo y Ferrocarril. La Construcción del Espacio Ferroviario en las Ciudades Medias Españolas. Instituto Universitario de Urbanística: Valladolid, Spain, 2007; Available online: https://1drv.ms/b/s!Alw91UAhEipthq5Ju3VENIcTvHklpg (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Aguilar Civera, I.; Navascués, P. Las Estaciones Ferroviarias de Madrid, su Arquitectura e Incidencia en el Desarrollo de la Ciudad. Servicio de Publicaciones del Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- González Fraile, E. Las arquitecturas del ferrocarril: Estación de Valladolid. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain, 1997. Available online: https://portaldelaciencia.uva.es/documentos/61567a86f4a2be56234420dc?lang=de (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Usón, E. La Estación Internacional de Canfranc. Ámbit: Barcelona, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Fernández, F.J. La arquitectura del ferrocarril de posguerra en Bilbao. Las estaciones ferroviarias y la concreción de una nueva imagen de ciudad. Rev. TST 2010, 18, 220–240. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Corral, A. Estación de Ferrocarriles de la Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro del Norte en Valencia. Génesis, de la Idea al Proyecto, de los Materiales a la Construcción. Coleccón Tesis Doctorales, Fundación de los Ferrocarriles Españoles, Madrid, Spain, 2017. Available online: https://tecnica-vialibre.es/documentos/Libros/AuroraMartinez_Tesis.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Cuéllar, D.; Martinez-Corral, A. History, architecture, and heritage in the railway station of Almería (1892–2017). Labor Eng. 2018, 12, 306–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Ballesteros, N. La Estación de ferrocarril Madrid-Delicias (1875–2011), Arquitectura, usos y Fuentes Documentales; Museo del Ferrocarril: Madrid, Spain, 2012; 1201p, Available online: https://museodelferrocarril.org/estacion/pdf/delicias_dt1201phf.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Aróstegui Chapa, B. Auge y abandono de las grandes estaciones europeas y su transformación con la llegada de la alta velocidad. P+C Proy. Ciudad. Rev. Temas Arquit. 2017, 8, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Palau, E.J.A.; Asensi, M.H.; Aymerich, A.T. Modelo morfológico de crecimiento urbano inducido por la infraestructura ferroviaria. Estudio de caso en 25 ciudades catalanas. Scripta Nova Rev. Electrónica Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2016, 20, 527. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/ScriptaNova/article/view/304132/393829 (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Santos y Ganges, L. Ciudades andaluzas y caminos de hierro en la historia: Aportaciones desde el urbanismo. 150 Años Ferrocarr. Andal. Balance 2008, 2, 721–765. [Google Scholar]

- González Yanci, M.P.; Casas Torres, J.M. Los Accesos Ferroviarios a Madrid, su Impacto en la Geografía Urbana de la Ciudad; Instituto de Estudios Madrileños: Madrid, Spain, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Faus Pujol, M.d.C. El ferrocarril y la evolución urbana de Zaragoza. Geographicalia 1978, 2, 83–114. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=59685 (accessed on 15 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Santos y Ganges, L. Burgos y el Ferrocarril, Estudio de Geografía Urbana. Instituto Universitario de Urbanística: Valladolid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaide, R. El Ferrocarril en la Ciudad de Barcelona 1848–1992, Desarrollo de la red e Implicaciones Urbanas; Fundación de los Ferrocarriles Españoles: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lalana Soto, J.L. Establecimientos de grandes reparaciones de locomotoras de vapor: Los talleres de Valladolid. Rev. De Hist. Ferrov. 2006, 4, 45–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar, D.; Jiménez-Vega, M.; Polo-Muriel, F. Historia de los Poblados Ferroviarios en España; Fundación de los Ferrocarriles Españoles: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Quintana, C. Vivir a Orillas de las vías del Ferrocarril. Viviendas Sociales de Ferroviarios en Oviedo, 1939–1975. Actas Congreso Historia Ferroviaria-Gijón: Mataró, Spain, 2003. Available online: http://www.docutren.com/HistoriaFerroviaria/Gijon2003/pdf/p3.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Pérez Igualada, J. La Ciudad de la Edificación Abierta: Valencia, 1946–1988. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2006. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=74351 (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Peris Sánchez, D. El barrio de Pio XII. 2014. Available online: http://www.miciudadreal.es/2014/06/18/el-barrio-de-pio-xii-viviendas-cr6/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Cuéllar, D.; Martínez-Corral, A. Una casa para nuestros padres: Una aproximación a las cooperativas de viviendas en España (1960–1985). In Actas del IV Congresso Internacional sobre Património Industrial. Cidades e Património Industrial; TICCIH-Universidade de Aveiro: Aveiro, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar, D.; Martínez-Corral, A. Cada vez menos obrera, cada vez menos ferroviaria: Vivienda y ferrocarril en España en torno a la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. In Actas del Congreso Internacional Pueblos Obreros y Ciudades Fábrica; Museu Nacional de la Ciéncia i la Tècnica de Catalunya: Terrassa, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar, D.; Martínez-Corral, A. Las soluciones constructivas de la vivienda social ferroviaria en la segunda mitad del siglo XX: Un patrimonio a estudio. In Actas de las Jornadas Internacionales de Patrimonio Industrial Incuna: Resiliencia, Innovación y Sostenibilidad; Col. Los Ojos de la Memoria, 21, CICEES: Gijón, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar, D.; Martínez-Corral, A. Las instalaciones eléctricas en las viviendas de nueva construcción durante el franquismo (1939–1975): El caso de las promociones ferroviarias. In Actas del Quinto Simpósio de Historia da Electrificação. Presentado en Electricidade, Cidades e Quotidianos a Electricidade e a Transformação da Vida Urbana y Social; Universidade de Évora: Évora, Portugal, 2019; Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1znscsNsYHgiQx-A4n-VIQiGENYpfE792/view?usp=drive_open&usp=embed_facebook (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Martínez-Corral, A.; Cuéllar, D. Las soluciones constructivas en la vivienda durante el franquismo: El caso de la vivienda ferroviaria. Inf. Construcción 2020, 72, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar, D.; Martínez-Corral, A.; Cárcel Carrasco, J. Planes, Materiales, Lugares: Análisis de la Vivienda Social Ferroviaria en España, 1939–1989. 3ciencias, Área de Innovación y Desarrollo. 2022. Available online: https://covifer.hypotheses.org/files/2022/03/COVIFER_2022-Planes-materiales-lugares.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Moya González, L. La vivienda social en Europa: Alemania, Francia y Países Bajos desde 1945; Mairea Libros: Madrid, Spain, 2008; Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=338454 (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Paricio Ansuátegui, I. ¿Por qué la vivienda mínima? Jano 1972, 1, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Paricio Ansuátegui, I. Las razones de la forma en la vivienda masiva. Cuad. Arquit. Urban. 1973, 96, 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Calduch, J. Temas de Composición Arquitectónica; Espacio y Lugar: Valencia, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Fernández, F.N. Normalizar la Utopía: Un Proyecto de Sistematización de la Normativa en Vivienda Social. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2014. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=91583 (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Muntañola Thornberg, J. La Arquitectura como Lugar; Edicions UPC: Barcelona, Spain, 2001; Available online: https://upcommons.upc.edu/handle/2099.3/36597 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Pallasmaa, J. Habitar; Editorial Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. La Economía de las ciudades. Edicions 1975, 62. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/412525315/Jacobs-La-Economia-de-Las-Ciudades (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. The Architecture of the City; MIT Press: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeira, M.J.; Durán-Villa Francisco, R.; Taboada-Failde, J. Urban Vulnerability in Spanish Medium-Sized Cities during the Post-Crisis Period (2009–2016). The Cases of A Coruña and Vigo (Spain). Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muxí Martínez, Z. Revisar y repensar el habitar contemporáneo. Rev. Iberoam. De Urban. 2010, 3, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini, L. Integrating mobility and urban development agendas: A manifesto. Plan. Rev. 2012, 48, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R. Urban Development on Railway-Served Land: Lessons and Opportunities for the Developing World; University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. 2009. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/71v7m90b (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Elmqvist, T.; Andersson, E.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Olsson, P.; Gaffney, O.; Kazuiko, T.; Folke, C. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granath Hansson, A.; Lundgren, B. Defining Social Housing: A Discussion on the Suitable Criteria. Hous. Theory Soc. 2019, 36, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, N.; Pareja Eastaway, M. Sustainable Housing in the Urban Context: International Sustainable Development Indicator Sets and Housing. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 87, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Web2: Paisaje Transversal—Oficina de Planificación Urbana Integral. (s. f.). Available online: https://paisajetransversal.com/ (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Alba Dorado, M.I. Design of a Transdisciplinary Methodology for the Identification and Characterisation of Industrial Landscapes. Heritage 2022, 5, 3881–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba Dorado, M.I.; Oliveira, E.R.d. Aproximaciones en el diseño de una metodología científica para la identificación, caracterización, valoración e intervención en el paisaje industrial ferroviario, 26. In Anais do VI Congreso Internacional de História Ferroviaria; Argentina Yerba Buena; Architecture, City and Environment: Portugal, 2017; pp. 118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, S.H.T. Metodologias de Avaliação de Edifícios do Patrimônio Ferroviário Paulista. In Memória Ferroviária e Cultura do Trabalho: Balanços teóricos e Metodologias de Registro de Bens Ferroviários numa Perspectiva Multidisciplinar, Brasil; 2019; pp. 211–238. Available online: https://memoriaferroviaria.assis.unesp.br/wp-content/documentos/livro_v1.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Web3: Research Guides: How to Choose Data Analysis Software: Qualitative Analysis Software. Available online: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/c.php?g=567658&p=3940638 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Madgin, R.; Lesh, J. (Eds.) People-Centred Methodologies for Heritage Conservation: Exploring Emotional Attachments to Historic Urban Places; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Bases de la investigación cualitativa. Técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. Rev. Logos Ciencia Tecnolgia. 2012, 3, 172–173. [Google Scholar]

- López de Lucio, R. Construir Ciudad en la Periferia: Criterios de Diseño para áreas Residenciales Sostenibles; Mairea Libros: Madrid, Spain, 2007; Available online: http://oa.upm.es/13373/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).