1. Introduction

Inscribing a place on UNESCO’s register as a World Heritage Site (WHS) is a long-drawn process, and both the process and the listing have often produced mixed results [

1,

2]. There are several examples where places listed as a WHS gain more popularity and more tourism [

3]. But there are also examples where there has only been a marginal impact of listing a place as a WHS on its popularity for tourism or even heritage management [

4,

5,

6]. Yet, in other instances, there has been a negligible influence of the listing on some places, and these places continue to struggle to achieve the desired outcome. While a good amount of literature is available about the listing process or evaluating the impacts of listing, there is not much discussion of places that are known for their universal values but are not able to obtain the status of World Heritage despite making necessary efforts to get that status. There could be many reasons for not being able to capitalize on such heritage for the global audience.

Sarnath is one such place in India that has been on UNESCO’s “tentative list” for close to 25 years (since 1998). This is the place where the Buddha [563–483 BCE] delivered his first sermon after his enlightenment in ca. 529 BCE. As such, alongside Bodhgaya (where the Buddha attained Enlightenment), Lumbini (where the Buddha was born), and Kushinagar (where the Buddha died), Sarnath is considered one of the most sacred sites by Buddhists on a Buddhist pilgrimage circuit in India. While both Bodhgaya and Lumbini are renowned Buddhist pilgrimage centers that are listed as WHSs and attract millions of visitors, the same cannot be said of Sarnath and Kushinagar [

7]. This paper aims to examine the trajectory of Sarnath’s development as a Buddhist pilgrimage center and what could being listed as a WHS means for its future. In doing so, this paper focuses on identifying endogenous and exogenous factors that influence the articulation of heritage and how that intersects with tourism and pilgrimage economy in Sarnath.

Although the focus here is on Sarnath, the findings from this study are applicable to a wide range of heritage sites in Asia for multiple reasons. Sarnath in located 10 km from the center of Varanasi city—a major Hindu pilgrimage site—and this locational aspect, where important sites belonging to two different religions or faiths are in proximity, is a common occurrence in the Indian subcontinent [

8]. How the proximity of heritage sites influences the development of one over the other is a question germane to the region, which is home to several religions that have been patronized for centuries by rulers and empires. Sarnath is a Buddhist site situated in a complex socio-cultural fabric of Hindu and Muslim populations. The story of its growth may be typical to many such places that are nestled within a different dominant religious landscape. There are several reasons that make the study of Sarnath quite significant if the complexities of managing heritage sites in the Asian subcontinent are to be understood in a holistic manner.

This paper aims to find answers to two questions: (a) what are the factors influencing the growth and development of Sarnath as a Buddhist pilgrimage center? and (b) how does this trajectory of growth intersect with the process of inscribing Sarnath as a WHS and what it means for heritage management in Sarnath? These answers are sought through a critical review of government reports and scholarly literature, and an analysis of the data gathered from interviews conducted with stakeholders in Sarnath in December 2019. The remainder of the paper has five sections. In the next section, relevant literature around Buddhist sites is reviewed to arrive at a conceptual framework to study Sarnath. The third section provides an overview of Sarnath’s growth as a Buddhist pilgrimage center. The fourth section discusses the endogenous and exogenous factors that have influenced the process of listing Sarnath as a World Heritage Site. Concluding remarks offering a nuanced understanding of heritage management of Buddhist sites, such as Sarnath, situated in a different religious-cultural context of Hindu sites, such as Varanasi, are presented in the concluding section.

2. Understanding Buddhist Sites in India

The syncretism between Buddhism and Hinduism is all too known, but somehow scholarly work about Buddhist sites is relatively limited compared to the vast amount of scholarly work on Hindu pilgrimage sites. Many studies have examined Hindu pilgrimage sites using the sacred complex model, and it would be a good starting point to examine the applicability of this model to Buddhist sites as well. Based on the ritualistic tradition of pilgrimage, this model is built around the three components of sacred geography, sacred specialists, and sacred performances [

9]. Sacred geography means all physical elements, including landform, landscape, rivers, flora, and fauna, are connected to some divine manifestations through myths and legends. Sacred specialists are those that provide services and assistance to pilgrims to understand a particular sacred geography. Priests, gurus, monks, ascetics, and others in religious occupations constitute the broad category of sacred specialists/religious functionaries. The interactions with the divine through a variety of rituals that are mediated by sacred specialists and performed by pilgrims are collectively termed sacred performances [

10]. This model is also employed by interchanging “sacred” with “religious” as the sacred is often made accessible through frameworks of religious beliefs and practices [

11,

12].

The sacred complex model is only partially helpful in explaining the pilgrimage economy of Buddhist sites, because of the different heritage they possess and reflect. For example, stupa and caves are part of the sacred geography of Buddhism, but there is hardly any ritual activity involving a material culture of offerings, such as incense sticks, food, and clothes, for a deity of the scale that is seen in Hindu sites. Buddhist monks and preachers may provide spiritual counsel and guidance but are not necessarily sacred specialists in the sense that is implied in Hindu pilgrimage sites. Similarly, ritual performances differ considerably in a Buddhist sacred site and may involve more of silent prayers, meditation, and internal worship compared to the pronounced extravagant ritual performances of Hindu sites [

13]. This is not to say that these aspects are completely missing; rather, they are much subdued and smaller in scale. Therefore, there is a merit in considering at least some aspects of this model in explaining the functioning of a Buddhist pilgrimage site.

The growth and evolution of a pilgrimage center can be better explained using a historical geography approach, as suggested by Shinde [

14]. Employing this approach in the study of the Hindu pilgrimage site of Vrindavan, it is shown that a pilgrimage site evolves due to a process of reproduction of the sacred space by its custodians. This process involves patronage relationships that run the cultural economy of pilgrimage and contribute to the building of necessary infrastructure for pilgrims and devotees, as well as interrelationships of religious and non-religious institutions in maintaining this economy and the sacredness of the place [

14]. The regular building and rebuilding of religious infrastructure enhances and eulogizes the “spirit of place” (genius loci), which acts as a resource that attracts pilgrims and devotees [

15]. The practice of accessing, knowing, and experiencing the spirit of the place engages hosts and custodians with visitors in a myriad of relationships that characterize the nature of visitation (as pilgrimage, tourism, pilgrimage tourism, heritage tourism, or a mix of all).

This concept of custodianship and patronage (in some form) is crucial for maintaining sacred landscapes and has been aptly utilized in the case of Buddhist sites as well. Recent studies of Buddhist sites such as Bodhgaya, the main pilgrimage center for Buddhists, have shown how it was rediscovered only in the last century and is being rebuilt through the efforts of international Buddhist associations and the support from the Indian government that was obtained via cultural diplomacy [

16,

17]. It is well known that most sites related to the Buddha were in ruins, when they were uncovered and documented by colonial administrators and archaeologists. Scholars have identified the following key elements for better understanding the Buddhist sacred landscape in India: revival of Buddhist places by connecting them to historical accounts of the Buddha’s life events; building of monasteries to enliven the archaeological nature of Buddhist sites; building a pilgrimage economy around transnational religious networks of monks and Buddhist followers; as well as promoting Buddhist teaching and philosophy that brings non-Buddhist followers to Buddhist sacred places [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Due to their archaeological legislation, the custodianship of most Buddhist sites lies with the government, which generates some complex relationships between the state and Buddhist religious authorities. Since most sites are situated in a non-Buddhist socio-cultural fabric, there is lack of local patronage. Thus, the responsibility of rebuilding and providing patronage is shouldered by international Buddhist institutions, and this adds a completely different layer of complication to the sustenance of Buddhist pilgrimage economy in Buddhist sites. In the Himalayan belt where one finds reasonable presence of Buddhist populations, the main anchor are the monasteries where custodian monks and patronizing local communities generate a more lively, vibrant, and active practice of Buddhism [

20,

21]. These are fast emerging destinations for cultural tourism. Newer Buddhist sites such as Dharamshala (Himachal Pradesh) have been created as sacred places by Tibetan refugees [

19] under the patronage of the 14th “Dalai Lama” Gyalwa Rinpoche, also known as Tenzin Gyatso. Many such sites have more of a cultural tourism economy rather than a traditional pilgrimage-based economy.

Using these key concepts of sacred geography as the resource, custodianship, and patronage, this paper now turns to examining the growth and evolution of Sarnath as a Buddhist pilgrimage center and its journey toward its nomination as a World Heritage Site.

3. Study Area and Methodology

Sarnath is one amongst the four most important sites associated with the life of the Buddha: here, he preached his first sermon in 529 BCE. The other three are Lumbini (where he was born); Bodhgaya (place of his enlightenment); and Kushinagar (where he attained parinirvana). After his enlightenment at Bodhgaya, he came to a deer park in Sarnath and presented the Dhamma talk on the Four Noble Truth. From here, he wandered across the Indian subcontinent to spread his teachings. Thirty-six years later, the Buddha once again visited Sarnath with many disciples to deliver “religious discourses and teachings, mostly challenging the superstitious rituals, sacrifices and totemism performed under the Brahminic traditions. This second visit was later followed by several visits to Sarnath” [

8]. Another legend associated with the deer park makes this place sacred. According to a tale from the Nigrodhamiga Jataka, at Sarnath (Isipatana), the Buddha was born as a Golden Deer in his previous life and, at that time, “had saved the life of a pregnant deer” based on which the “king of Kashi declared this territory as ‘protected area’, protected from hunting and preserved for mendicants and deers” [

8]. Stupas were built in the sixth century to commemorate these places visited by the Buddha, which form the main constituents of the sacred geography of Sarnath.

At present, Sarnath is a settlement that has grown around an archaeological park containing the remains of these stupas. Located about 10 km from the center of Varanasi, it has about 11,000 residents. In terms of tourism infrastructure, it has a handful of monasteries and hotels. Fieldwork was conducted by the first author in Sarnath in December 2019 (ethics approval was obtained from the university). This fieldwork was part of a larger project focusing on understanding visitation trends and sustainability issues related to pilgrimage, tourism, and heritage in the key sites of the Buddhist pilgrimage circuit, viz., Bodhgaya, Kushinagar, Sarnath, and Lumbini (in Nepal).

In Sarnath, employing the case study method, 16 representatives of key stakeholders, including government officials (3), monks and managers of monasteries (5), hotel owners and managers (4), tour operators (2), and local community leaders (2), were interviewed by the first author. The 45 min duration interviews were conducted in the Hindi language at the workplace of the interviewees, and questions about pilgrimage facilities, visitor activities, heritage interpretation and management, and other stakeholders and world heritage status were asked. These questions helped to unpack the meanings around the key concepts of Buddhist heritage as a resource for pilgrimage and tourism, the influence of custodianship on patronage relationships, and the management of heritage. The responses were transcribed into English whilst thematic analysis was conducted. Given the small scale of the settlement and the archaeological nature of the attractions, saturation of responses was reached early, and the qualitative data obtained from these interviews are sufficient to obtain a holistic understanding about issues in Sarnath.

4. Sarnath: History and Growth as a Buddhist Pilgrimage Center

Sarnath followed the cycles of growth and decline like other Buddhist sites and Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent (for a full history of Sarnath under different empires, see Singh and Rana, 2011, and Dhammika, 2009). The ruins at Sarnath were first discovered in 1793 when a local royal family member named Jagat Singh excavated the area scouting for building materials to be used in establishing a new neighborhood. Subsequently, Alexander Cunningham (1834−1836) led the excavations that were followed by other colonial officers. Singh documents the extent of Sarnath’s archaeological area, which includes many monuments and stupas and measures about 16.73 ha, and within this area, “the religious and historical monuments are spread over an area of 9.59 ha” [

8]. (Part of this is shown in

Figure 1.) In recent memory, the most significant historical moment for Buddhists was the performance of the 14th Kalachakra Puja (a Buddhist Tantric ritual process) at Sarnath under the guidance of H.H. the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, in 1991.

In the next paragraphs, the contemporary pilgrimage economy of Sarnath is explained using the sacred complex model.

Sacred geography: The sacred geography of Sarnath comprises the Deer Park, which is the place of delivery of the first sermon, Dharmarajika Stupa, Dhamekha Stupa, Chaukhandi Stupa (the spot where the Buddha met his first disciples), Mulagandhakuti Vihara (the place where the Buddha spent his first rainy season), the Ashoka Pillar, and the Bodhi tree planted by Anagarika Dharmapala (grown from a cutting of the Bodhi Tree at Bodhgaya). All these are designated as protected monuments and constitute the archaeological park under the custody of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Outside this core, which can be called the formal sacred territory, there are a few monasteries where pilgrims stay during their visit.

Custodianship: As mentioned above, the archaeological park is under the total control of the ASI, which regulates all activities as per the provisions of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958, and the Antiquities and Art Treasure Act, 1972. Besides the archaeological park, the ASI also manages the Sarnath Archaeological Museum, which contains artefacts from the excavations at Sarnath (one of its prized possessions is the famous Ashokan lion capital which is engraved as the National Emblem of India and is present as a national symbol on the Indian flag). Outside the archaeological park, the monasteries are on private lands.

Patronage: Although Buddhist pilgrims have been travelling to Sarnath for a long time, the necessary religious infrastructure to service them has been slow to develop. Sarnath was only a small settlement in the early part of this century. Besides the ruins, the first known temple, called Mulagandha Kuti Vihara, was built by the Ceylonese monk Anagarika Dharmapala over a period of 25 years (1904–1931). The main patrons were Buddhist benefactors from overseas. In 1922, the Myanmar temple was built. Chinese Buddhists from Calcutta began the construction of a Chinese Monastery in 1939. For the next fifty years, there was hardly any construction of monasteries, and Sarnath represented an agglomeration of four villages surrounding the ruins [

22]. A Japanese temple was built in 1986, and about a decade later, in 1999, a majestic Tibetan Monastery going by the name of Vajra Vidya Institute opened its doors. It again took more than a decade before a Thai temple and monastery, a Vietnamese monastery, and a Korean monastery were established in Sarnath. Therefore, in total, there are just about seven monasteries in the locality that offer support to pilgrims.

The timeline of the establishment of different Buddhist monasteries shows that the growth of Sarnath as a Buddhist pilgrimage center has been sluggish, compared to other places such as Bodhgaya, which presently boasts of more than 200 monasteries of varying sizes [

7]. In terms of attractions, the Thai monastery and its gardens are the most visited because of their close vicinity to the archaeological ruins. Other monasteries have very limited flow of pilgrims and visitors.

Pilgrimage: The scale of pilgrimage economy in Sarnath is much smaller compared to other Buddhist sites, such as Bodhgaya and Lumbini. One indicator is the number of monasteries, as mentioned above. The other is visitor numbers. In 2017 (data from pre-COVID-19 times), Sarnath had a total of 763,259 visitors, while Lumbini had almost double the number, at 1,400,000, and Bodhgaya had three times the number, at about 2,040,625. In all the sites, domestic tourists dominated while the share of foreigners was similar at about 13%. It is clear that a smaller proportion of people visit Sarnath.

Sarnath is not as celebrated as other places for Buddhist rituals and performances. The ASI prohibits the performance of any rituals at the main stupa, which is in the archaeological park. Thus, many pilgrims choose to perform their pilgrimage rituals at the monasteries where they stay. However, this is not the same as offering prayers at the actual spot. It was found that the monasteries have a fixed calendar of events in which their patrons would participate, and this means the vibrancy associated with regular pilgrimage is almost not visible. The most notable event in the history of Sarnath was the 14th Kalachakra Puja (a Buddhist Tantric ritual process) that H.H. the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, performed on 30 December 1990–1 January 1991. It was at this event that thousands of Buddhist pilgrims converged at Sarnath.

Accommodation: For any pilgrimage place, accommodation is a crucial factor in determining its pilgrim flows. In Sarnath, however, accommodation is limited. It has only two dharmshalas (pilgrim lodges), of which one was built in 1935. In terms of private accommodation, there are around 15–20 hotels and guesthouses; many were established only in the last five years or so. A guesthouse owner, who continues to operate the oldest guesthouse, explained how these accommodation options came about:

“Around 1994–1995, the then state government was pondering on how to develop Sarnath as a “Buddhist Tirtha-Kshetra”. That time, the government took the initiative and instructed that people who had more rooms than what they needed could use the additional room for “paying guest” with the only condition that the owner must stay in the same house and customers should have homely feel and eat food at home. It was under this scheme that I got the license for operating as a “Paying Guest House”; 2–3 other guesthouses were also established but could not run successfully. I provided services as a family so at my house, we welcomed strangers, but treated them as family members” (Interviewed on 22 December 2019).”

Sarnath has neither attracted philanthropic accommodation nor private enterprise of the hotel industry. One hotel owner pointed out that “Sarnath is overshadowed by Banaras accommodation [there are more than 500 hotels in the neighboring city of Banaras or Varanasi]”.

Therefore, overall, one sees that Sarnath has been an important Buddhist site but has not evolved as a major pilgrimage center like Bodhgaya or Lumbini. How that has played out in relation to its listing as a WHS is the topic in the next section.

5. Endogenous and Exogenous Factors Influencing Development of Sarnath

Among the four sacred sites associated with the life events of the Buddha, i.e., Lumbini (the birthplace), Bodhgaya (the place of enlightenment), Sarnath (the place of first preaching), and Kushinagar (the site of nirvana), only the first two are inscribed in the World Heritage List. The proposal for inscribing the ancient monuments of Sarnath was submitted to the UNESCO’s WHC under the category of “cultural property” by the ASI in July 1998, and shortly afterwards, it was enlisted in the “Tentative List of Heritage”. The proposal was not clear about the characteristics corresponding to the defined criteria, and the timespan management plan for at least twenty years was not incorporated. In 2019, a revised and more comprehensively developed proposal was submitted. However, it is still under review. As this section will show, there are plausible endogenous and exogenous factors that have influenced the trajectory of growth related to pilgrimage and heritage in Sarnath and contributed to its current state.

5.1. Endogenous Factors

Sarnath is primarily controlled and managed by the state government as an archaeological park. In following its mandate, the government is maintaining the place by providing “public amenities including new dustbins, garden benches, water coolers, wooden railings; tree guards and a Cultural Notice Board (consistency added for signage)” (Officer, ASI, interviewed on 21 December 2019). The officer further mentioned about their own challenges in managing the place, such as “increased vehicular movement near archaeological site which causes vibration and has potential to damage the ancient structures, dealing with illegal construction in the 100 m buffer around the park, constantly looking out for monks and tourists who put golden foils on ruins and cross over the Vedika as part of offering to the Buddha” (interviewed on 21 December 2019). It is particularly the last activity that is strictly prohibited in the park.

Pilgrimage activity is restricted to the confines of Buddhist monasteries, and, thus, the monasteries represent the active sacred space, but they also have their own mandates. Gandhi observes that “While the various temples are maintained by their respective national organizations, the most sacred spaces and monuments fall under the government’s administration” [

23]. As such, there are contestations between the state’s approach and what Buddhist followers (for whom this is the most sacred place) want. A monk lamented, “the place is legally dead (in ASI terms), but monks believe that this is live and breathing for them; ASI believes the monument is disturbed by the monks/and raises questions of maintenance” (interviewed at a monastery, 21 December 2019).

The idea of disturbance is expanded by not allowing any kind of construction in the buffer zone of 100 m radius outside the archaeological park. Such rules and prohibition imply that no physical development occurs in the vicinity of the sacred core, and this works counter to the needs of pilgrimage economy, wherein some amenities and facilities are a must around sacred sites for the benefit of visitors. For a robust pilgrimage economy, religious institutions provide most of the facilities. Like one monk said, “monks and monasteries are necessary for offerings prayers and rituals; they are necessary to maintain the sites as living places—keeping it alive as they give life” (interviewed on 22 December 2019). However, the monasteries also evoke some resentment amongst locals. Some monasteries are seen as “neglected places with no proper values as the patronizing countries are different”, while others that are functioning are considered to fulfill only one purpose—“to provide for those coming from outside including accommodation and food” (guesthouse owner, interviewed on 21 December 2019).

The government attempted to reinvigorate Buddhist heritage in Sarnath by establishing a Tibetan institute in 1967–1968. This institute headed by a Rinpoche was initially situated within the Sanskrit University and the Banaras Hindu University. It became an active learning center for scholars of Tibetan Buddhism, but it has no role in the pilgrimage economy of Sarnath. In 2009, the institute was elevated to the level of an autonomous organization under the Union Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and named the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies (CIHTS). The institute continues to teach courses on Buddhist philosophy, art, and astronomy and sees a regular influx of Buddhist scholars but has nothing to do with the pilgrimage economy. According to a hotel owner, it is an “independent island in Sarnath—it is not connected with local heritage” (interviewed 19 December 2019).

Of course, Sarnath and its archaeological site is considered a special sacred place for Buddhist adherents and is one of the most venerated places of Buddhist pilgrimage. However, Sarnath has been deprived of its spiritual relevance by a short-sighted Governmental Administrative System through their political vision. Take, for instance, the issue of a special entrance fee that international visitors are charged for visiting the monuments in the archaeological park, or the rules that do not allow pilgrims to perform their rituals like lighting candles and incense at the monuments. Surprisingly, only a few individuals had complained about this, and the majority do not support Buddhists who contest such charges and rules. Buddhists feel that such charges together with other neoliberal agendas under a “secular policy” are against the basic ethics and philosophy of “peace, justice and equality among all beings” that the Buddha gave to this world [

24]. Sarnath lacks the serenity and spirituality of a Buddhist site; all one can see at Sarnath are busloads of tourists being given a guided tour. At most, they may spend an hour or two chanting in the name of religion, despite its lack of spiritual setting.

Moreover, the government presents and promotes Sarnath as a tourist destination rather than a pilgrimage site, and this has “shaped, altered, or intensified the contested nature of Sarnath” [

23]. For urban dwellers living in the highly urbanized areas in the vicinity and seeking a good place for recreational purposes, the archaeological park with its expanse of open and green space presents a best-fit option. Almost three decades ago, Sinha observed that “visitors’ behavior reveal that the peace and tranquility required for religious meditation and worship are threatened by increasing recreational use in the vicinity of the ruins” [

22]. The situation is not different even in the present day, as pointed out by Gandhi: “most of the domestic tourists [from within the country] were using the various ruins as walkways or picnic tables” [

23]. In fact, during the fieldwork, the authors also observed that a photo session was being conducted for a bride and a groom as pre-wedding shoot (see

Figure 2).

Like pilgrimage, tourism is also contested at Sarnath. As a place, it represents more of a village transformed under the pressures from nearby urban growth, rather than a tourist place. A large proportion of people in Sarnath still follow rural lifestyles and seem to be rather oblivious to the benefits of tourism. Gandhi found that “most locals, with the exception of the tour guides, do not view the tourist industry as a great source of income for sustainable livelihood [

23].” In the interviews, we heard some criticisms as well: “For locals there is no awareness; no hospitals; no college education; no drainage; caste conflicts- tensions and nobody wants to change their lifestyle” (local community leader, interviewed on 23 December 2019). A tour guide expressed his frustration, “there are no good quality restaurants, so tourists do not stay even for a meal” (interviewed 21 December 2019). All these sentiments are echoed even in the government’s work, as seen from the words of a staff at the Visitor Center: “Sarnath is not really an important tourist place” cited in [

23]. Even at the monasteries, tourism does not seem to be welcomed. Gandhi cited a monk from Vajra Vidya Monastery as saying:

“I know. This is the nicest temple in town, but I am glad that we do not get many tourists. This is a place for studying the Dharma, for offering prayers, and for meditating. It would be a shame if we were suddenly surrounded by tourists who are only interested in taking selfies.”

Sarnath represents a complex site where pilgrims, monasteries, governments, and local community leaders cannot seem to come to a unified vision to help identify where the problems are coming from. And some of these complexities are also because of systemic neglect by the institutions involved in decision making about Sarnath.

5.2. Exogenous Factors

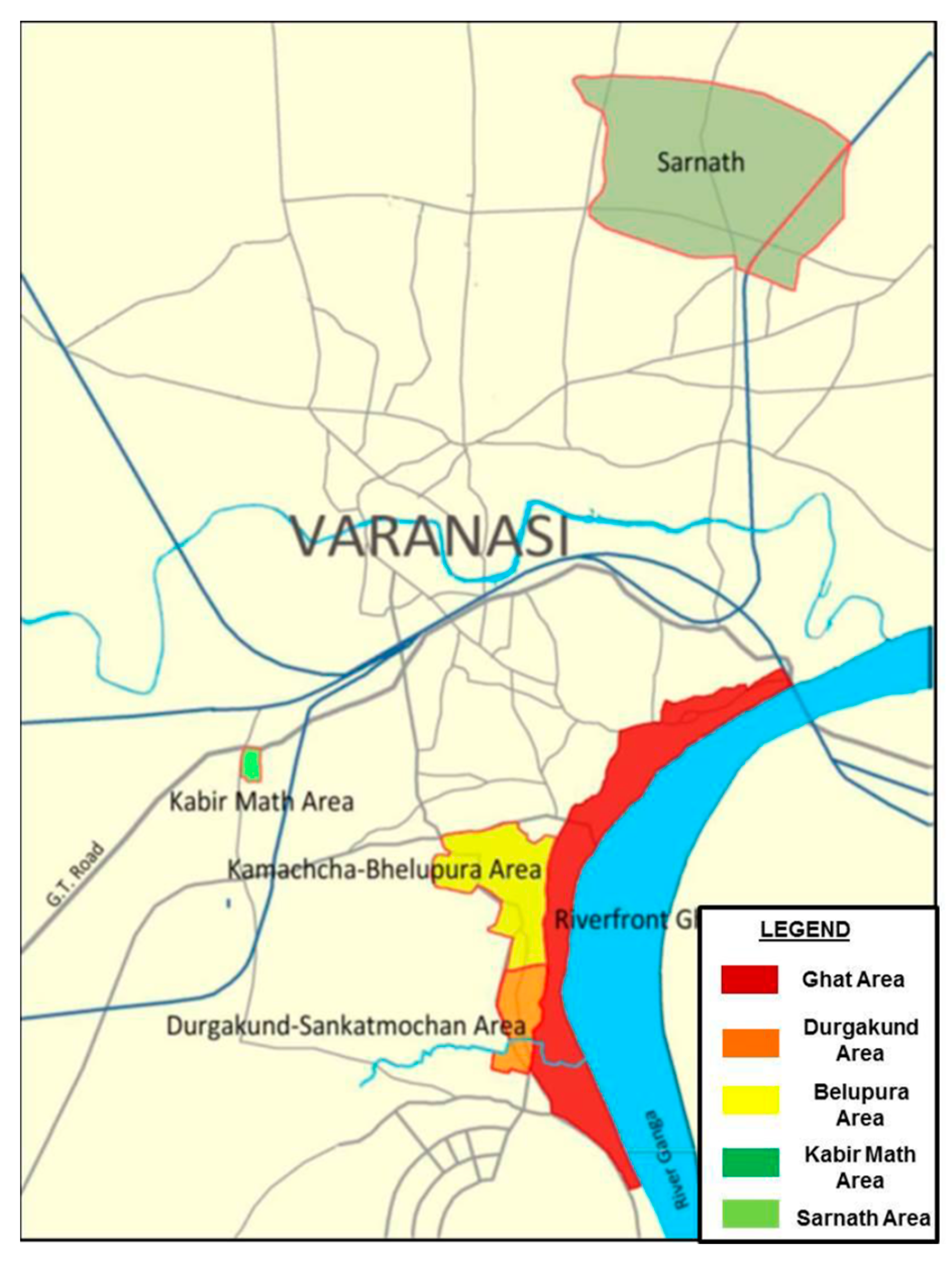

The settlement or locality of Sarnath (as referred to in most government reports) is situated in the periphery of the city of Varanasi (see

Figure 3, which indicates the distribution of heritage zones). Governed by the Varanasi Municipal Corporation, Varanasi is spread over an area of about 82.1 sq.kms and has a population of about 1.65 million (in 2021). As per this administrative system, Sarnath is only an electoral ward (number 44)—one amongst the 91 wards in the city of Varanasi [

25]. The municipal government website also does not have any information on Sarnath except for its mention as a Buddhist heritage site and a tourism attraction. There are hardly any data available at this micro-level, and this makes any kind of demographic analysis quite difficult. Thus, one must rely on anecdotal information and the data collected through primary surveys and interviews. As per the local councilor, the population of Sarnath is around 11,000 (interviewed on 20 December 2019). Sarnath is marginal both in the sense of its location and population.

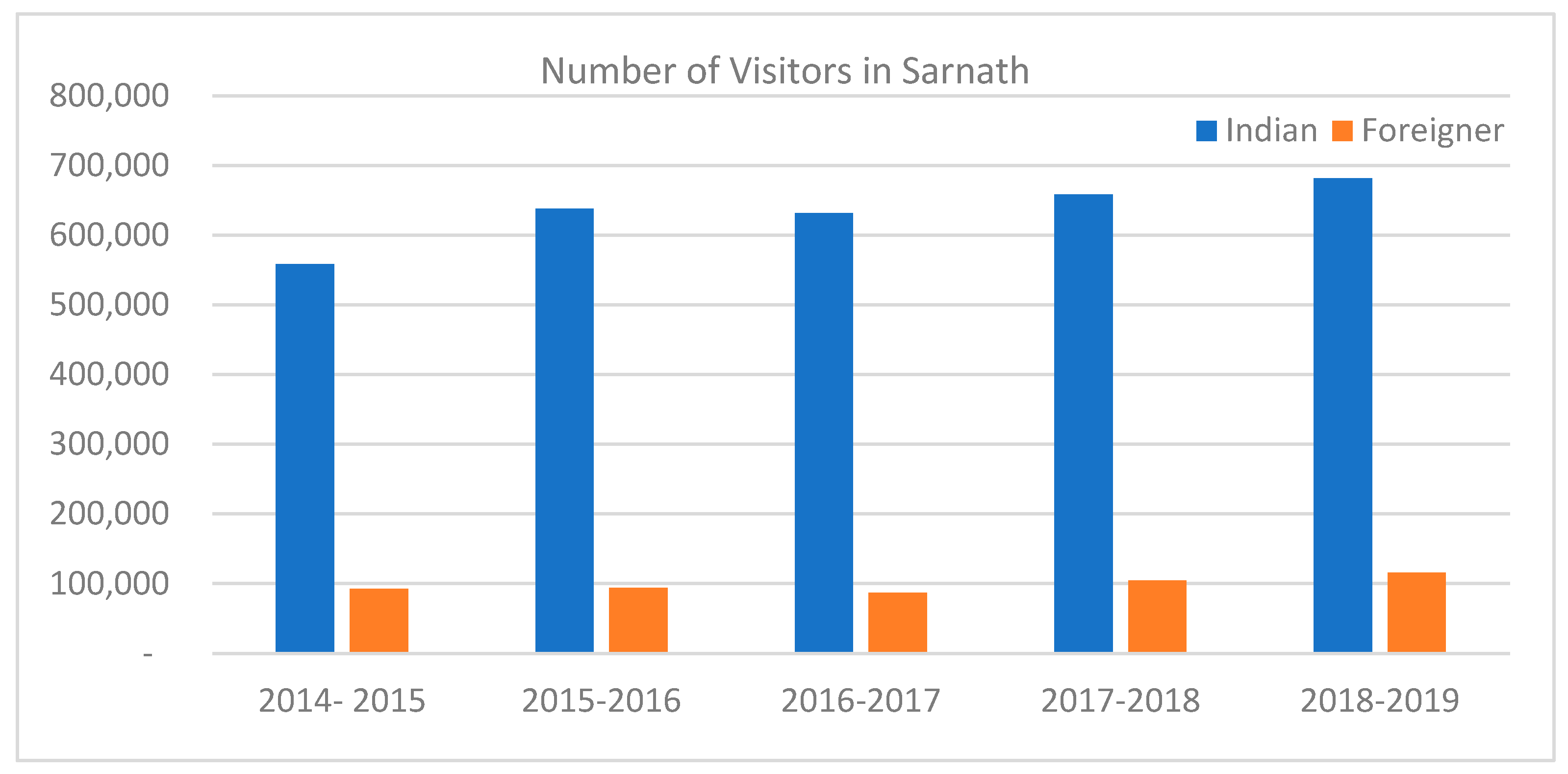

As an attraction, Sarnath seems to have marginal importance. This is illustrated by the data available on visitors and visitation pattern (although this dataset is laden with discrepancies, as shown below). The data procured from the Visitor Center at the Excavated Remains of Sarnath (managed by the ASI, Sarnath Circle, Sarnath) during the fieldwork in 2019 and mapped in

Figure 4 suggest that, generally, foreign visitors account for just around 15% of the total visitors to Sarnath—this is not too different from what has been observed in other religious sites, for example, see [

7,

15].

Before moving further, it is important to state that there is variation in the data about tourist numbers from different sources. The data on visitors obtained from the ASI office could be considered as more reliable because they are based on sales of tickets. However, the numbers gathered here are different compared to the information provided by the UP State Tourism Department for the same year (

https://www.uptourism.gov.in/en/post/Year-wise-Tourist-Statistics (accessed on 20 December 2022)): the ASI data show a total of about 763,259 visitors at Sarnath (ticketed), whereas the Tourism Department data suggest almost double the number, which is 1,455,271, and for the same period, it recorded 6,282,063 visitors for Varanasi. This means that less than 25% of visitors had visited Sarnath, an important tourist site just 10 km away from the city center. Further analysis suggests that 95% of the total visitors to Varanasi are domestic, whereas the corresponding figure for Sarnath is around 70%. From these data, it could be deciphered that domestic tourists are relatively fewer in Sarnath, a Buddhist site which appeals mainly to international Buddhist pilgrims. Varanasi (Banaras) acts as a tourist hub for all tourist activities; Sarnath is only a half-day trip: “Most of them [foreigners] were only in Sarnath for the day, but they had been living in Varanasi for at least a few days [

3,

4,

5] in general … For many, Sarnath is ultimately a destination for a day trip when domestic or international travelers want to get away from the crowds of Varanasi” [

23]. This is not surprising as the list prepared by the Municipal Corporation shows more than 400 hotels registered in Varanasi, whereas there are only five in Sarnath. There is very little tourism economy sustained in Sarnath.

The other exogenous factors affecting Sarnath are its systemic and systematic neglect/ oversight from the governmental discourse about heritage and tourism. One of the earliest attempts to work toward conservation of Sarnath was in 1988 when a team consisting of the Ministry of Tourism and Civil Aviation, the Government of India, the National Park Services, the United States Department of the Interior, and selected students and faculty members from the University of Illinois designed “A Master Plan for Tourism Development” [

22]. This plan was not implemented [

23]. However, this documentation contributed to the need of listing Sarnath as a WHS. The initial nomination dossier for WHS listing was prepared and submitted on the 3 July 1998. As per the UNESCO guidelines, these documents need to be revised and updated at least once every ten years. Gandhi (2018) cited a consultant’s report from 2013 which stated that “the ASI had not defined any specific criteria for the selection of sites to be nominated on the tentative list… There were no guidelines for development of sites selected… [and] there was a lack of proper planning that has contributed to the stagnant status of the site even today” [

23]. Currently, there are no authentic and exhaustive travel guides or maps specifically for Sarnath; one has to use the more popular map and guidebook of Varanasi (although a short guidebook about the archeological park itself is available from the ASI, which was first published in 1956 [

26] and has been reprinted several times).

Sarnath has hardly seen progress in relation to its heritage tourism or pilgrimage tourism despite its proximity to Varanasi. While Varanasi has been a site for the implementation of many governmental initiatives, Sarnath has been consistently sidelined. Sarnath’s development as a distinct place for heritage and tourism development is also not seen in other urban development-oriented schemes, such as the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM 2009–2015) and the more recent Varanasi Smart City. The JNNURM (2009–2015) encouraged the formation of Heritage Cells and the preparation and implementation of Heritage Development Plan. In 2011, the Architectural Heritage Division, Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), recommended a Heritage Development Plan for Varanasi, but this was focused only on selected Hindu heritage monuments within the old city of Varanasi and lacked consultation with local community [

27]. In 2016, Varanasi was nominated for development under the Smart City Mission. The proposal for the development of Varanasi as a smart city was built around “Six Key Pillars”: Suramya (picturesque or beautiful) Kashi; Nirmal (clean) Kashi; Surakshit (safe) Kashi; Samunnat (progressive and proficient) Kashi; Ekikrit (integrated) Kashi; and Sanyojit (planned). Singh has critiqued the accomplishments of a smart city: “Recent field studies and participatory observations find weak institutional (governmental, community-based and NGOs) coordination, lacking capacity and power to enforce regulation and policies, often also linked to various degrees of corruption; altogether they serve as major obstacles to heritage preservation” [

27]. Thus, the implementation of projects under the six pillars have been fragmented and are no different from what has been found in the implementation of the Smart City Mission in other Indian cities (for further insights on this, see [

28,

29]). What is important to note is that these proclamations are all about Kashi/Banaras/Varanasi (these are names of the same place) and have very little for Sarnath; thus, the conservation of heritage in this important city is dominated by the Hindu heritage of Varanasi and its dominant image as Kashi (the name of the sacred city in Hindu scriptures).

A big push for Varanasi came when the Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who contested the elections from this city (as the sacred Hindu city), was elected in 2014 as a Member of Parliament. Subsequently, Varanasi was included in the central government’s sponsored schemes specifically designed to revive heritage in historic cities, such as the PRASHAD (Pilgrimage Rejuvenation and Spiritual Augmentation Drive) and HRIDAY (Heritage City Development & Augmentation Yojana). The intent was to “promote an integrated, inclusive and sustainable development of heritage sites (cities), focusing not just on the maintenance of monuments but also on the advancement of the entire ecosystem including its citizens, tourists and local businesses [

27].” Under the HRIDAY, Varanasi received around INR 893 million (i.e., USD 14.9 million) for various projects, including riverfront development of the sacred river Ganga and temple corridors (for a fuller discussion, see [

27]). Similarly, the PRASAD scheme (launched by the Ministry of Tourism) aimed at infrastructure development for tourism funded several high-value projects (approximately INR 550 million) in Varanasi, including the development of the “Panchkoshi Path” (the sacred boundary route around the core city), a Pilgrim Facilitation Center, the development of several roads and signages, and river cruise on Ganga [

30]. Not a single project was prepared for Sarnath. Even in other schemes such as the Swadesh Darshan Scheme that were aimed at enhancing Buddhist heritage, Sarnath seems to be overlooked from the sites to be developed under the Buddhist pilgrimage circuit.

As a place, Sarnath is peripheral to the complex urban issues that dominate the city of Varanasi. Its location on the fringe has not been able to persuade policymakers to look at it either as a site for heritage, tourism, or pilgrimage and accord it any special treatment. It remains one amongst many outer wards. On the contrary, by treating it as sub-urban place, infrastructure projects, such treatment plant for water and sewerage services, are proposed, which has the potential to further dilute its unique value. A glimmer of hope was seen in April 2021 when the long-drawn proposal to get the “Iconic Riverfront of the Historic City of Varanasi, India” inscribed in the WHC tentative list was approved. On the sidelines of this listing, there was re-appraisal of the riverfront together with other unique attributes of the city to include Sarnath (a Buddhist site) and the ancient temple of Kardameshvara in a recent plan, which was initiated by the central government of India in July 2021, and a committee for preparing the dossier for this “Kashi-Sarnath-Kardameshvara Sacred and Heritage Path” was formed. In this religious and spiritual landscape, six sacred complexes were identified that link the sacred path from Sarnath (north) to Kardameshvara (south), covering about 16.5 km and consisting of six areas forming a conglomerated complex of such units (Kshetra); the first one was “Sacredscapes of Sarnath: Buddhist” (Dhamek and other ancient sites, Jain monasteries (Suprparshvanatha), and Hindu sanctuaries (Sarangnath temple)). Unfortunately, due to political reasons and the priority for some other aspects, the government authorities decided to close this project in January 2022 [

31].

The preceding discussion clearly indicates that Sarnath remains excluded from the dominant discourse of heritage, tourism, and development. The status quo of Sarnath results from a combination of historical, political, and bureaucratic factors—all nested within a lack of political will. Its custodian, the Archaeological Society of India, in following its mandate, has shown concerns about the integrity of the site and, therefore, has been reluctant to promote mass pilgrimage; the Hindu majority government (both at state and local municipal levels) has assigned lower priority to it as a Buddhist site; it is not imagined as being central to the sacred geography of Varanasi, and there is no administrative structure that is ready to support Sarnath for its heritage and tourism. A local community leader summed it up quite appropriately: “Sarnath is the same as what was 10 years ago or even before that because of no government efforts; it is not up to the standards of an international pilgrim center (interviewed on 22 December 2019)”. It could be argued that fragmentations and contestations exist at many levels, including spatial (at the site level and town level), social (between visitors and managers), cultural (imagination and promotion of heritage) levels, and all of these contribute to the poor state of heritage and tourism in Sarnath.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In answering the two interrelated questions regarding the development of Sarnath as a Buddhist pilgrimage center—what factors have influenced this trajectory of development and how they intersect with the inscribing of Sarnath as a WHS—this paper presents a narrative of underutilization of the Buddhist heritage of Sarnath for tourism and conservation and its sluggish growth as a Buddhist pilgrimage center. In recent years, the Buddhist pilgrimage circuit in India has gained immense popularity: the government and the private sector are promoting this circuit which has long been traversed by devout Buddhist followers (mainly international). This circuit comprises Bodhgaya, Sarnath, Kushinagar, and Lumbini as the main sites, while the other four sites of Sravasti, Sankssia, Rajgir, and Nalanda also feature in many itineraries. However, not all sites are equal in terms of visitor flows; Bodhgaya has more visitors than Sarnath, and so on. This paper explains how the peculiar context of Sarnath as an archaeological relic on the fringes of popular Hindu pilgrimage sites partially explains its stunted growth, and therefore, a pilgrimage circuit may not ensure that all sites participate or benefit in the same manner.

This paper identifies several endogenous and exogenous factors that reinforce Sarnath’s place at the margin in relation to Varanasi. Given the syncretism of Buddhism and Hinduism, the paper imagines that the conceptual scheme of the sacred complex model of Hindu pilgrimage centers could be applied to Buddhist sites such as Sarnath. To a considerable extent, this has been helpful in explaining how, in spite of being a sacred place for Buddhist pilgrims, the archaeological setting controlled by a government agency (ASI) does not support any active religious practices under the pretext of heritage preservation, and this causes a disconnect between sacred geography and sacred performances (rituals). As a result, most pilgrimage-related rituals are confined to nearby monasteries of international Buddhist associations and monks, where limited monastic activity takes place. Here, it is difficult to find any signs of a vibrant pilgrimage economy (even in relation to other sites, such as Bodhgaya, in the Buddhist pilgrimage circuit); pilgrims come for a fleeting visit. This is not the case for Varanasi where millions of Hindus come to perform practices related to Hinduism. Using the historical geography approach may provide better answers in understanding pilgrimage and tourism in Buddhist heritage sites, particularly those that are situated in a different socio-cultural and religious context. The case of Sarnath illustrates the inherent conflicts between the site’s spiritual, archaeological, and touristic significance.

Sarnath seems to underperform as a tourist attraction as well. It is mainly a destination for day trips where most visitors are driven by recreational needs and an escape into the vast areas of greenery on the margin of a bustling and crowded city. With a handful of hotels and an even smaller number of quality eating places, Sarnath does not have a tourism economy of its own. There is hardly anything to spend on for visitors, except for occasional snacking and cheap imitation variety items that have limited souvenir value. All tourism-related expenses (accommodation, transport, tours, guides, etc.) are concentrated in Varanasi. Sarnath has not been able to benefit from the popularity and attraction of Varanasi. Similar marginality is seen in the management of heritage in Sarnath. Most initiatives and projects for heritage conservation are implemented in Varanasi, whereas Sarnath continues to be “protected” and that protection is a barrier to the conservation of intangible cultural heritage, which depends on the site. Moreover, the development of the controversial light and sound show in Sarnath as an attraction for tourists exposes an insensitivity toward the spiritual dimensions of the heritage of this place (this is where the Buddha delivered his first sermon). Even in terms of governance and administration, Sarnath remains at the periphery of all decision making, which means its continued neglect in the development agenda.

Being on the margins (geographical location, cultural milieu, and religious imagination) of Varanasi has affected Sarnath in many ways, but the most significant effect is the maintaining of its status quo in terms of WHS listing. As explained earlier, endogenous factors, such as the incomplete nature of pilgrimage as an archaeological site (as rituals cannot be performed), the lack of robust pilgrimage economy, and poor level of service, are acting as barriers to mobilizing the local community toward meaningful engagement with Sarnath’s heritage being recognized as World Heritage and the benefits that may accrue with that label. Moreover, the social structure of a rural population living with surrounding urban villages and the laid-back attitudes suggest that the community does not see and rely on tourism economy as a sign of progress. It seems that the interest of the government in preparing the dossier for the nomination of Sarnath (mainly through the ASI) was inspired by Bodhgaya. However, both Buddhist sites are vastly different, as shown in this paper. Moreover, Sarnath is competing with the Hindu site of Varanasi. Given the dominance of Hindu faith in the state (and in nation-wide imagination), the government would put Varanasi first (and yet, it is only in 2021 that the Iconic Riverfront of the Historic City of Varanasi was included in the tentative list of WHS). Thus, the explanations for the sluggish growth of Sarnath also, to a large extent, explain why it has remained on the tentative list for more than 25 years.

Given the syncretism of Buddhism and Hinduism and that many Buddhist sites are in the vicinity of Hindu pilgrimage sites, one would imagine that both Hindu sites and Buddhist sites would have similar treatment for their heritage. However, as this paper has highlighted, there is a complex relationship of Sarnath as a Buddhist heritage site with Varanasi as its neighbor. Sarnath is at the margins in all respects—heritage, tourism, governance, and as a place. Is there something that can be learnt from the examples of similar sites in Nepal, which exhibits a great degree of syncretic relation between Hindu and Buddhist heritage? [

4,

5]. Thus, the question that will continue to haunt Sarnath is whether Varanasi’s label as a World Heritage Site will help Sarnath. Also, will the dossier that was prepared for Sarnath in 1998 (25 years ago) ever move ahead for its recognition and identity as a World Heritage Site? And most importantly, will such listing bring real development for Sarnath?