Abstract

Underwater cultural heritage (UCH) is a diverse and valuable resource that includes shipwrecks, sunken cities, and other submerged archaeological sites. It is an important part of human history and culture and can significantly benefit society. However, various factors often neglect and threaten UCH, including climate change, pollution, and human activities. Several factors, including technological advances, the development of international law, and the growing awareness of the importance of cultural heritage, have influenced the evolution of the concept of UCH. In the early days of underwater archaeology, the focus was on recovering artifacts and treasures from shipwrecks. However, over time, there has been a shift towards a more holistic approach to the management of UCH, which emphasizes the importance of in situ preservation and the involvement of local communities. This review provides a chronological analysis of the evolution of the concept of UCH over the past 70 years and examines the main international conventions and charters developed to protect UCH. The review also discusses the relationship between UCH and marine protected areas (MPAs), the marine environment, and the coastal landscape.

1. Introduction

The marine environment has always interested scientists and researchers in various disciplines. With more than 70% of the planet’s surface covered by water, marine space is still largely unexplored in many respects. Over time, the international community has achieved an ever-greater awareness of the cultural and historical value of the priceless heritage that our seas and oceans conceal [1,2,3].

Underwater cultural heritage (UCH) means “all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character which have been partially or totally underwater, periodically or continuously, for at least 100 years” [4].

The importance of studying and preserving UCH is stated in three important international conventions and charters: the 1982 UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea), the 1996 ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) Charter on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage, and the 2001 UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. The 2001 convention recommends protecting ancient shipwrecks or submerged archaeological sites in situ before considering recovery. In marine archaeology, many wooden or metallic artifacts are found in different states of conservation, depending on the environment in which they are discovered [5], and their recovery is not always the best strategy for pursuing their preservation and conservation.

Underwater cultural heritage constitutes an invaluable resource that needs acknowledgment and proper treatment so that it may continue to offer significant benefits to humankind. However, UCH has been neglected in most marine planning attempts despite its indisputable value. Lately, however, the opportunities and challenges for UCH have been considerably different [6].

For the above reasons, it is necessary to clarify the meanings and the evolution of the notion of UCH. For this purpose, here are some questions that can guide this exploration for a definition: What is UCH? How can we define it? How has the notion of UCH evolved and developed over the years? An investigation of the literature based on notions and evolutions of the legislative context on the topic is necessary. In this review of the literature, the main international conventions and charters are considered. The different semantic definitions of UCH have changed over time, and therefore, it is necessary to understand the evolution of the concept during the last 70 years. This article presents the definitions of UCH and describes the evolution of the concept, along with describing the definitions of marine protected areas, the marine environment, and the coastal landscape.

2. International Charters and Conventions on UCH

The first development of the concept of underwater heritage was shaped by the UNESCO recommendation of 1956, in which the international principles for archaeological excavation (also valid in the marine environment) were defined [7].

When the World Heritage List was established for the first time [8], i.e., when the list of sites that represented particular locations of exceptional importance from a cultural or natural point of view was defined, despite the central role of the sea in the spread of cultures and civilizations since the dawn of human history, the first list of World Heritage Sites, as drawn up in 1978, did not contain any sites with a maritime or submarine location.

One might, therefore, think that the interest in underwater heritage is recent. It became a topic in vogue only after the invention of the first underwater air-breathing device in 1943 by Cousteau and Gagnan [9]. However, the first complex underwater archaeological recovery in history (although one without a positive outcome) dates to 1446 and was undertaken by Leon Battista Alberti. “His proverbial antiquarian curiosity was pinned on the famous Roman imperial ships that the emperor Caligula had built for his idleness in Lake Nemi and whose memory had never faded” [10]. However, awareness of this type of heritage has remained entirely latent for many centuries.

2.1. Chronological Analysis of the Evolution of the Legislation on UCH

It is necessary to wait until 1982 to see the birth of the first international text [11], which, although it was drafted to outline the laws of the sea, also includes two articles that refer specifically to underwater archaeological sites and historical objects and provides that the same “shall be preserved or disposed of for the benefit of mankind as a whole, particular regard being paid to the preferential rights of the State or country” [11].

The first specific reference to the submerged cultural heritage dates back to the ICOMOS charter of 1990, which defines the archaeological heritage as “all vestiges of human existence and consists of places relating to all manifestations of human activity, abandoned structures, and remains of all kinds (including subterranean and underwater sites), together with all the portable cultural material associated with them” [12].

The focus of the charter spans structures and infrastructures, such as ports, harbors, and marine systems. Interest has been growing because of the development of underwater exploration technologies and techniques, which has unfortunately opened the road to looters, with subsequent damage to the heritage itself. This prompted the European Council to adopt the 1992 European Convention on the Protection of Archaeological Heritage, with the recommendation to create archaeological parks for underwater heritage [13].

The International Committee on the Underwater Cultural Heritage (ICUCH) was founded in 1991 by ICOMOS Australia to promote international cooperation in the protection and management of underwater cultural heritage and to advise the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) on issues related to underwater cultural heritage around the world. As a supplement to the 1990 charter, in 1996, ICUCH authored the drafts that led to the ratification of the first document on protecting and managing underwater heritage, i.e., the Charter on the Protection and Management of the Underwater Cultural Heritage [14]. Hand in hand with the need for knowledge and study, awareness of the importance of this type of heritage has also developed in terms of the significant risks to which it is subject. Considerable importance is given to the increasing interest on the part of collectors in finds that come from the seabed; this alarming development is in part linked to recent advances in diving technology and may give rise to forms of looting. The enhancement of underwater heritage must deal with the problems of “protection”, whose solutions are not always easily feasible in a marine context; the action of promoting a submerged discovery, if not adequately reasoned (including through awareness programs for the local population), inevitably puts it at risk of depredation.

In the declaration of Syracuse, adopted in 2001 at the end of a conference on the cultural heritage of the Mediterranean Sea, it was outlined that “the Mediterranean countries have a special responsibility to ensure that the submarine cultural heritage they share is made known and preserved for the benefit of humankind” [15].

Following the International Conference, “Means for the Protection and Touristic Promotion of the Marine Cultural Heritage in the Mediterranean”, held in Palermo and Syracuse, Italy, on 8-10 March 2001 [15], the most recent international document on the subject as of today is the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage.

This document proposes (for the very first time) the definition of underwater cultural heritage as “all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character which have been partially or totally under water, periodically or continuously, for at least 100 years such as (i) sites, structures, buildings, artifacts and human remains, together with their archaeological and natural context; (ii) vessels, aircraft, other vehicles or any part thereof, their cargo or other contents, together with their archaeological and natural context; and (iii) objects of prehistoric character” [4].

The Convention sets out basic principles for the protection of underwater cultural heritage by outlining four main principles:

“Obligation to Preserve Underwater Cultural Heritage—State Parties should preserve underwater cultural Heritage and take action accordingly. This does not mean that ratifying states would necessarily have to undertake archaeological excavations; they only have to take measures according to their capabilities. The Convention encourages scientific research and public access.

In situ preservation as the first option—The in situ preservation of underwater cultural Heritage (i.e., in its original location on the seafloor) should be considered as the first option before allowing or engaging in any further activities. The recovery of objects may, however, be authorized for the purpose of making a significant contribution to the protection or knowledge of underwater cultural Heritage.

No Commercial Exploitation—The 2001 Convention stipulates that underwater cultural Heritage should not be commercially exploited for trade or speculation and that it should not be irretrievably dispersed. This regulation is in conformity with the moral principles that already apply to cultural heritage on land. It is not to be understood as preventing archaeological research or tourist access.

Training and information Sharing—States Parties shall cooperate and exchange information, promote training in underwater archaeology and promote public awareness regarding the value and importance of underwater cultural heritage.”

Following UNESCO’s Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (2001), the new stage of the current process of reappropriation of cultural heritage as a common value, a “popular” asset, is represented by the Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society [16], adopted by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the 13 October 2005 in Faro, effective since 1 June 2011 and ratified by Italy on the 23 September 2020 (House of Representatives). The Convention had the merit of defining an innovative and revolutionary concept of cultural heritage (CH), intended as the body of resources inherited from the past, identified by the citizens as the reflection and expression of their values, beliefs, knowledge, and traditions in continuous evolution. It recognizes the right of the single citizen and all humanity to benefit from CH, tempered by the responsibility of respecting it. These principles are the basis for the chain of research, conservation, protection, management and participation, and cultural dialogue, promoting the birth of a sustainable and multicultural social, political, and economic environment. It is a fact that UCH is increasingly required to have a social return beyond the cultural aspect; a positive impact on a community’s economic and social fabric is sought. On the other hand, the European Union guidelines promote Blue Growth and responsible and sustainable tourism linked to the sea and UCH.

Experiencing the past underwater has rapidly become an enormous asset in the leisure industry and the “experience economy”. This development implies risks and opportunities for protection as not all UCH can be enjoyed through direct access for various reasons; these include the position, depth, and safety/integrity of the assets and the safety and diving capabilities of researchers, citizens, stakeholders, and tourists.

This is particularly true for the submerged deposits of shipwrecks (hull or cargo and onboard equipment). Those that contain inorganic cargo and are located at a limited depth can be accessible, but only under favorable visibility conditions, and to a few divers, who are only a small percentage of the community interested in exploring its past.

After more than 20 years of the Sofia Charter for the Protection and Management of the Underwater Cultural Heritage [14] (5–9 October 1996), a Udine summit (8–9 September 2022) outlined the most recent experiences in the field in the Italian panorama. The discussions and considerations led to a shared proposal, the Udine Charter for the Underwater Archaeology [17]; this document represents the outcome of an intense debate within the scientific community regarding UCH and the related challenges to guaranteeing the development of the research while at the same time promoting a virtuous model of public engagement with the archaeological heritage.

On the 8th and 9th of September 2022, the first workshop aiming to update the Udine Charter took place to ensure the inclusion of the aspects more related to internal waters, i.e., rivers and lakes, and the incorporation of opportunities offered through the development of new remote sensing technologies.

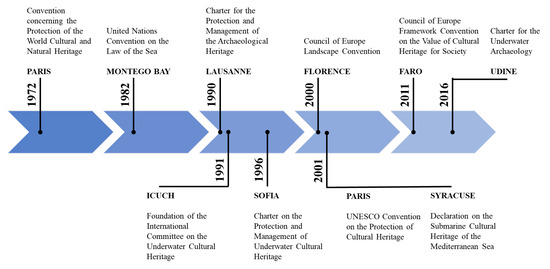

The conventions, charter, and declarations listed above are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Main conventions and charters on the concept of underwater cultural heritage in recent decades.

2.2. The Concept of In Situ Conservation

The long evolution of the concept of heritage also affects the submarine heritage; the latter is therefore not configured as a nineteenth-century statement but as a very recent conquest, if we can define it that way. It is noteworthy that in the 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage [4], for the first time, in situ conservation is explicitly indicated as the preferred choice. It also underlines the importance of and respect for the historical context of cultural heritage sites and their scientific relevance, recognizing that this heritage is (under normal circumstances and for some materials) preserved underwater thanks to the low rate of deterioration due to the absence of oxygen. Therefore, recovery from the seabed is not always automatically justified. Moreover, considering the state of conservation and submersion methods, recovery is not always the action that guarantees maximum preservation of the asset.

For this reason, it is important to consider innovative technologies for documentation and study, even for those who do not have the skills or the ability to go underwater. These technologies should be adopted without ignoring the need for historical and archaeological knowledge, which is indispensable for a careful and intelligent application of today’s technical solutions.

In situ conservation of underwater archaeological heritage is a complex operation in terms of methodological approach and operational workflow. It requires many experts (archaeologists, geomatic specialists, engineers, chemists) to integrate the available archaeometric information. This approach should not be considered to be a sum of the different contributions but rather a complementary coordination towards the improvement of the knowledge of the heritage.

3. Marine Protected Areas

In recent years, the conservation and the valorization of cultural heritage have been of interest in international agreements, as it is important to protect the cultural value of in situ conservation. For underwater cultural heritage, the 1992 European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage outlines the importance of creating “reserve zones” to preserve evidence to be excavated later. It is, therefore, crucial to explain the current system of protection of the marine environment, starting from the concept of “marine protected areas”, which aims not only to ensure the protection of the archaeological underwater heritage but also serve as the starting point for the institution of archaeological parks.

In the 1980s, the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) defined the term “Marine Protected Area” as “Any area of intertidal or subtidal terrain, together with its overlying waters and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by legislation to protect part or all of the enclosed environment” [18,19]. With these definitions, the IUCN intended to protect not only the seabed but also the water, the flora and fauna, and the archaeological remains above it, ensuring not only the protection of the biodiversity but also the protection of the pieces of cultural evidence.

Protected areas are divided into six types, depending on their objectives [20]:

- Category I—Protected area managed mainly for science or wilderness protection (Strict Nature Reserve/Wilderness Area);

- Category II—Protected area managed mainly for ecosystem protection and recreation (National Park);

- Category III—Protected area managed mainly for conservation of specific natural features (Natural Monument);

- Category IV—Protected area managed mainly for conservation through management intervention (Habitat/Species Management Area);

- Category V—Protected area managed mainly for landscape/seascape conservation and recreation (Protected Landscape/Seascape);

- Category VI—Protected area managed mainly for the sustainable use of natural ecosystems (Managed Resource Protected Area). (IUCN, 1994)

MPAs (marine protected areas) were established to create an integrated marine-land system of protected environments. The adoption of the specific action of protecting the marine environment is even more necessary for the Mediterranean Sea due to the amount of relevant archaeological evidence that is disseminated. For this reason and “because of their scientific, aesthetic, historical, archaeological, cultural or educational interest”, in order to safeguard the resources, natural sites, and cultural heritage of the Mediterranean Sea, with the possibility of identifying MPAs for preserving relevant sites, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) Regional Seas Program proposed a regional convention [21] to prevent pollution from various human sources in the Mediterranean Sea. The convention was adopted in 1976, updated in 1982 [22], and amended in 1995.

Additionally, the IMO (International Maritime Organization) has established some guidelines for the Identification and Designation of Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas (PSSAs) [23]:

“A PSSA is an area that needs special protection through action by IMO because of its significance for recognized ecological, socio-economic, or scientific attributes where such attributes may be vulnerable to damage by international shipping activities. An application for PSSA designation should contain a proposal for an associated protective measure or measures aimed at preventing, reducing, or eliminating the threat or identified vulnerability. Associated protective measures for PSSAs are limited to actions that are to be or have been approved and adopted by IMO, for example, a routing system such as an area to be avoided.

The guidelines provide advice to IMO Member Governments in the formulation and submission of applications for the designation of PSSAs to ensure that in the process, all interests—those of the coastal State, flag State, and the environmental and shipping communities—are thoroughly considered on the basis of relevant scientific, technical, economic, and environmental information regarding the area at risk of damage from international shipping activities.”

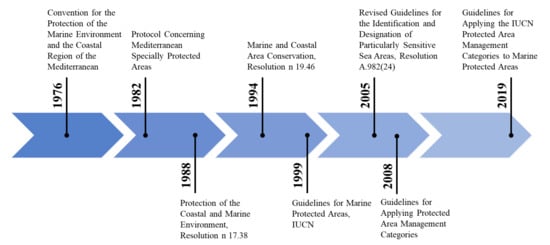

The conventions, declarations, and guidelines above are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Main conventions, declarations, and guidelines on the definition of marine protected areas.

4. The Marine Environment and the Coastal Landscape

In the above sections, the concept of underwater cultural heritage and its evolution during the last 70 years has been explained.

A strong bond links underwater cultural heritage with the cultural identity of the Mediterranean Sea; in fact, the coast of the Mediterranean has been a place for cultural and economic exchanges of which archaeological traces and remains are the witnesses. Therefore, it is essential to fully understand the problematics of the conservation of these artifacts through proper documentation techniques, deepening theoretical and methodological aspects related to the management of coastal areas, and the integrated preservation of archaeological sites.

The challenges related to the documentation of coastal landscapes are complex and multifaceted. Some have already been addressed through various means. In contrast, others are yet to be explored, such as setting up innovative approaches using and reappropriating cultural content to preserve this invaluable treasure and transmit it to future generations. The methodological approach that underlies landscape or, better still, seascape archaeology is holistic, contextual, diachronic, and transdisciplinary. The landscape is the “living palimpsest”, no longer made up of isolated monuments but of “assets” related to each other, which only become comprehensible in terms of their historical, cultural, and social value if they are inserted into a “system” and framed within it.

4.1. The Notions of “Environment” and “Landscape”

The progressive emergence of the notion of “environment”, which did not exist in the 1948 Italian Constitution, was introduced in Italy by the Franceschini Commission (Commissione d’indagine per la tutela e la valorizzazione del patrimonio storico, archeologico, artistico e del paesaggio, created with the law L. 310 of 1964).

The management and protection of cultural heritage and the natural environment encountered various difficulties in Italy after the Second World War, following the emergence of the concept of “cultural heritage” instead of “historical-artistic heritage”.

Protecting the natural environment has suffered from a series of problems that are still unresolved today and which are linked to the expression “cultural and environmental heritage”, which seems to indicate that environmental heritage is not also cultural. As Oreste Ferrari writes, this “may seem like a simple question of terminology, but in reality, it is a substantial question, which has determined different types of behavior in the protection action” [24].

In Italy, the documentation of archaeological underwater and coastal sites has been, in recent years, an essential subject at various conferences and seminars, as the interest in this kind of heritage has increased over the last few decades. In particular, (again in Italy), numerous and significant disastrous events (earthquakes, land exploitation, coastal erosion, landslides, and floods caused by indiscriminate deforestation) have constituted further difficulties that require collective attention and public intervention.

The proceedings of World Environment Day (Held in Rome on 5 June 1985) subsequently promoted the unequivocal interconnection between the “historical-cultural” environment and the “physical-natural” environment. Thanks to this, diagnostic and monitoring systems have been developed that facilitate map-based documentation of the factors that increase the vulnerability of cultural heritage, with particular reference to anthropogenic and environmental phenomena.

The submerged heritage is closely linked to the marine and coastal landscape in which it is located, even though at the beginning of the twentieth century, the protection of landscape assets and the notion of “landscape” was legally considered in the same way as that of “things of art” [25]. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, since there was a need for a vision broader than the concept, we find a reference to the marine landscape in the European Landscape Convention, which extended the notion of landscape to “the entire territory of the Parties”, including “natural, rural, urban and peri-urban areas […], land, inland water, and marine areas” [26].

The concept of landscape and the definition of landscape heritage can also be extended to the coastal areas. Westerdahl introduced the first application of this concept internationally as “the whole network of sailing routes, with ports, havens, and harbors along the coast, and its related constructions and other remains of human activity, underwater as well as terrestrial” based on this approach; the landscape defined as such should be compared “to its terrestrial counterpart, but not just as an extension of the latter” also including “shipping, shipbuilding and fishing and their respective hinterlands, with nodal points of coast towns and land roads, fords, ferries, and inland waterways” [27].

The coastline, as a frontline, is something that has evolved over decades and centuries. It is correct to maintain—from the point of view of knowledge, interpretation, and preservation—that every shore, along with its related marine areas, is an expression of the way man has shaped and transformed natural sites to adapt them to his needs; they form a part of our cultural resources, and specifically our architectural and landscape heritage [28].

Analyzing the coastline through the same methods used for any other architectural expression, it is possible to define some criteria (conceptual, methodological, and practical) similar to those of the modern restoration culture. The main aim is to mediate the socio-economic needs to preserve the coasts as natural and historic-cultural systems and subsystems [29]. Following this approach, it is not correct to focus only on a single piece of heritage, but it is important to understand its relations with the surrounding territories; this implies the creation of paths and itineraries for historical and cultural promotion inside a new panorama of relations between each of the connected archaeological revelations, each of them understood in its authenticity and uniqueness [29].

4.2. Coastal Areas and the Land–Sea Duality

The relationship between the coastal areas and the land–sea duality has a strong cultural connotation and emblematically represents the symbol of the underwater archaeological heritage, whose conservation cannot preclude the study of its connections with the land. For this specific purpose, it remains crucial to develop new ways of integrating heterogeneous data in specific GISs (Geographic Information Systems), which can represent a good starting point for each conservation and valorization activity regarding the archaeological heritage and the landscape heritage.

The concept of the protection and valorization of coastal areas and the complex relation between sea and land have strong cultural values represented by the importance of many archaeological findings, whose preservation must be linked to the evaluation of historical and environmental dynamics that are in common with land above sea level.

Coastal areas have always been dynamic; natural factors and various anthropogenic factors have affected the seashore (especially in recent years). The study of underwater archaeological sites requires understanding and virtually reconstructing the coastline based on the interpretation of archaeological data and available geomatics, geologic, and geophysics data. Integrating data from those disciplines fosters the acquisition of knowledge about the coastal landscape and archaeology of coastal settlements.

The link between geological phenomena (proximity to a river, composition of the soil and the rocks) and the presence of archaeological evidence is very important; it is the main reason it is possible to find archaeological remains a hundred meters inland from the coastline. In the Mediterranean Sea, we have witnessed a coastline retreat that caused the submersion of human-made artifacts and structures (today, those sites vary in depth, from a few centimeters up to 3–4 m).

The study of the sea level and the interpretation of the causes behind the submersion of such archaeological remains are complex; there are several reasons, such as eustatic sea level change due to changes in the volume of water in the world’s oceans, net changes in the volume of the oceanic basins, vertical tectonic movements, coastal erosion, or mineral deposits formed during the accumulation of sediment on the bottom of rivers and other bodies of water. Each of those causes is related to a different method of studying how and why the phenomena occurred.

The changing coastline of the Mediterranean Sea over the last 2000 years has been drafted by Antonioli and Leoni [30] based on measurements performed on the Roman pool of the imperial period located in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Those structures’ strong relations with the sea level allowed us to understand useful information about that period’s historical sea level (and, therefore, its coastline).

Harbors, ports, and pools annexed to Roman villas were built to function with the activities related to the sea, and they demonstrated strong relations between the sea level and the geographical context. Documenting the relationships between the ports, the cities, and the territories is crucial to understanding their role in general maritime politics [31].

The integration of geomatics, geophysics, and archaeological data allows us to understand and reconstruct the coastline as it was in ancient ages and therefore allows not only the comprehension and study of the coastal landscape and the actuation of countermeasures against coastal erosion but also an understanding of the human impact on the recent phenomenon of climate change. This is helped by the possibility of chronologically classifying the archaeological remains along the shore.

The most recent geo-archaeological studies related to the Mediterranean Sea show that the main reason for the submersion of underwater heritage is linked to a slow increase in the sea level, which has caused a slight but noticeable regression of the coastline over the last 2000 years [32,33,34], with some more important tectonic movements (mainly local) such as the case of Campi Flegrei, which have caused a more significant submersion of several meters below the current sea level [35].

The study of this kind of data is important to define the relations between the submerged archaeological heritage and the coastline and the land, with the period and the context of the submersion also being considered in order to define a useful connection for valorization and protective actions.

In an optimal situation, MPA valorization and conservation projects should aim to contextualize the underwater heritage in the surrounding framework from an environmental and landscape point of view. Valorization and conservation projects should also ensure a system of services for enabling the fruition of the heritage; in this way, importance is given not only to the conservation but also to the valorization, keeping a balance between the anthropic risk and the need for promotion and making “visible the invisible”. This must be linked with research activities that aim to communicate scientific data in a fast and easy way, not only to scientists but also to the public (not from the point of view of tourist marketing, but for the promotion of the cultural and historical point of view of specific places and regions).

The idea of the coastal landscape, and the landscape in general, is not the aesthetic “panoramic view” concept, but rather the identity of the places, a compresence of nature, culture, and history, and the assumption of the aesthetic identity of the landscape as an integration of these three elements [36].

5. An Example of Political Action towards the Protection of UCH: The Italian National Superintendency for Underwater Cultural Heritage

This notable example is reported as it was one of the very first Superintendencies for Underwater Cultural Heritage to be established in Europe. Due to the many skills necessary for the protection, management, and enhancement of the sea and its riches, in recent years, the Sicily region has equipped itself with structures created with the specific purpose of carrying out research, investigations, recovery, and valorization of the underwater archaeological heritage, already a pre-eminent sector for the island during the post-war period. This is how, in 1999, the GIASS (Gruppo d’Indagine Archeologica Subacquea Sicilia—Sicily Underwater Archaeological Investigation Group) was formed by Prof. Sebastiano Tusa, who would later become the first superintendent for the Superintendence for the Cultural and Environmental Heritage of the Sea, established by the Sicily region in 2004 [37].

With the establishment of the Superintendency of the Sea, Sicily was (at the time) the very first administrative body in Italy and Europe to protect, manage, and enhance the culture of the sea. “Sea and culture is a combination that represents for us something inseparable which, in addition to being the daily object of the exciting path of research, knowledge, protection, and enhancement that we practice with professionalism and enthusiasm, can be for the future of this island something more than a tourist slogan” [10].

Later, in 2009, the Italian National Superintendency of Underwater Cultural Heritage was created. “The National Superintendency for Underwater Cultural Heritage is an office with special autonomy of a non-general managerial level under the Ministry of Culture of Italy. The Superintendency is responsible for protecting, managing, and valorizing national underwater cultural heritage”.

The National Superintendence for Underwater Cultural Heritage (referred to from now on as the “National Superintendency”), based in Taranto, oversees the performance of the activities of protection, management, and enhancement of the underwater cultural heritage referred to in Article 94 of the Code, as well as the functions attributed to the Ministry under the law of 23 October 2009, n. 157, concerning the ratification and execution of the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, adopted in Paris on 2 November 2001. To this end, it liaises with the Archaeology, Fine Arts, and Landscape Superintendencies.

In the Province of Taranto, the superintendent of the National Superintendency also carries out the functions of the superintendents of Archaeology, Fine Arts, and Landscape. The superintendent also exercises the functions referred to in Article 43, paragraph 4, on state institutes and places of culture present in the same territory and not assigned to other offices of the Ministry.

The National Superintendence has operational centers at the Archaeology, Fine Arts, and Landscape Superintendencies, with headquarters in Naples and Venice and the others identified with a subsequent provision.

6. Other Examples of Initiatives to Document and Promote UCH

For the present research aim, it is important to refer to other past and existing associations, administrative bodies, and projects related to UCH documentation and preservation. This section presents a list of some initiatives aimed at documenting, preserving, and promoting UCH. Below, some examples are presented and subdivided into different categories. The following list is by no means exhaustive, but it covers the main areas.

Italian associations and administrative bodies:

- Soprintendenza del Mare della—Regione Siciliana

- Soprintendenza Nazionale per il Patrimonio Culturale Subacqueo

- Fondazione Sebastiano Tusa

- AIOSS (Associazione Italiana Operatori Scientifici Subacquei)

- International associations and administrative bodies:

- ISPRS WG II/7—Underwater Data Acquisition and Processing

- The ICOMOS International Committee on the Underwater Cultural Heritage (ICUCH)

- UNESCO Underwater Cultural Heritage

- International institutes, centers, societies, and foundations:

- IKUWA (Internationaler Kongreß für Unterwasserarchäologie)

- Département des recherches archéologiques subaquatiques et sous-marines (Drassm)

- Centre Camille Jullian CNRS bureau d’architecture navale antique

- Arqueologia Nautica y Subacuatica

- Centro de Arqueología Subacuática

- Instituto para la Memoria Arqueológica Naval Hispánica

- National Park Service (NPS)—Submerged Resources Center

- Alexandria Centre for Maritime Archaeology and Underwater Cultural Heritage

- Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA)

- INA Foundation—Institute of Nautical Archaeology

- INA Turkey Bodrum Research Center

- The Honor Frost Foundation

- NAS Nautical Archaeology Society

- Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities

- The Turkish Foundation for Underwater Archaeology (TINA)

- The Leon Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies (RIMS)

- Institut Européen d’Archéologie Sous-Marine (IEASM) F. Goddio

- Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology

- Center for Underwater Archeology of Catalonia (CASC)

- Centre for Maritime Archaeology—University of Southampton

- The German Society for the Promotion of Underwater Archaeology (DEGUWA)

- The Albanian Center for Marine Research

- The department of underwater archaeological studies of The National Heritage Institute (INP) Tunisia

- Centre of Underwater Archaeology of the Ministry of Culture of Bulgaria

- Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia, Ljubljana

- International Center for Underwater Archeology in Zadar

- Croatian Conservation Institute—Underwater Archaeology

- Laboratory of Maritime Archaeology (LabMA), Kotor Montenegro

- AURORA Trust Foundation

- Projects, groups, and initiatives:

- Underwater Muse

- iMareCulture

- Fish&Chips

- BlueMed

- MedDive in the Past

- MUSAS

- AMPHITRITE

- The Pavlopetri Underwater Archaeology Project

- Archeologia Subacquea Speleologia Organizzazione (ASSO)

- SUNRISE Summer School

All these initiatives show how attention to the study, conservation, and promotion of UCH is now a reality established worldwide and that the promotion of the marine context and the production of new sustainable plans requires thorough knowledge of the condition, extension, position, and metric consistency of the archaeological remains and cultural sites underwater.

7. Discussions and Conclusions

The concept of heritage is often linked to that of conservation. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “heritage” as “property that is or may be inherited; an inheritance”; “valued things such as historic buildings that have been passed down from previous generations”; and “relating to things of historical or cultural value that are worthy of preservation” [38].

It is important to emphasize that conservation is not the only strategy to be adopted, even in these contexts. As also recalled by Carlo Federici, one of the most prominent experts in the conservation of documentary material: “Having established that we have to pass on to posterity the cultural heritage that we have inherited from our fathers, I would like to point out that we—as posterity—deserve the enjoyment of those testimonies of the past” [39]. For this reason, and above all because of the intrinsic difficulty of fruition that derives from in situ conservation (especially with underwater heritage), the ability to know how to plan interventions properly is of crucial importance for the enhancement and promotion that allow the use of the heritage, without endangering the heritage itself.

The founding principles of the Faro Convention [16] place the idea of heritage as a common good, as a resource for well-being and social cohesion; therefore, it appears to be a priority to enhance the submerged heritage and make it accessible to everybody, since by its nature it is not “handy” and it is in some respects “invisible” but it can be rediscovered and also made visible thanks to the creation not only of submerged archaeological parks and itineraries for divers but also through the use of evocative tools such as virtual reality and augmented reality, which can be used by and allow the involvement of a wider audience.

Underwater objects and heritage must also be studied by experts in fields other than diving (historians, architects, chemical engineers, preservationists). Because conservation in situ is often the only option, there is a growing need for documenting and mapping archaeological evidence of UCH, such as shipwreck sites of different ages and submerged coastal villages or cargoes of architectural construction materials that sank during transportation.

However, the marine environment should not be considered an ultimate limit from a technical point of view. Cooperation with the government can overcome difficulties. Research institutions and universities that allocate a proper amount of funding and establish training programs for highly qualified personnel will be able to fill the gaps between terrestrial and marine surveys.

Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) is a rapidly evolving field of study with significant implications for understanding humanity’s past and stewardship of the marine environment. Although UCH has been largely neglected in marine planning attempts, the opportunities and challenges for its management are changing rapidly.

To better understand the importance of UCH and develop effective strategies for its management, it is necessary to clarify the meanings and evolution of the notion of UCH. A literature investigation based on notions and evolutions of the legislative context on the topic has been presented in this paper.

The term UCH was first coined in the 1950s and has been defined in various ways. The most recent definition of UCH is provided by the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, which defines it as “all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character which has been partially or totally under water, periodically or continuously, for at least 100 years”.

UCH is often located in MPAs, areas of the marine environment protected due to their conservation value. MPAs can help protect UCH from various threats, including pollution, overfishing, and illegal salvage. However, it is important to note that not all MPAs are created equal, and some MPAs may not effectively protect UCH.

UCH is also closely linked to the marine environment and the coastal landscape. UCH sites can provide important information about the historical environment and the people who lived in coastal areas. Additionally, UCH sites can be valuable to coastal communities, attracting tourists and providing educational and recreational opportunities.

In conclusion, UCH is a diverse and valuable resource that plays an important role in human history and culture. It is important to protect and preserve UCH for future generations. The international conventions and charters developed to protect UCH provide a valuable framework for its management. However, more research is needed to better understand the impacts of climate change and other anthropogenic stressors on UCH.

By clarifying the meanings and evolution of UCH and conducting more research on its importance and management, we can better protect and preserve this valuable resource for future generations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and F.C.; methodology, A.C.; investigation, A.C.; resources, A.C.; data curation, A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.C. and F.C.; supervision, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Goncalves, R.M. Legal aspects of the underwater cultural heritage in Spain. Current state legislation. Aspectos jurídicos do patrimônio cultural subaquático na Espanha. A legislação estatal atual. Veredas do Direito 2017, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda Gonçalves, R. La Protección Del Patrimonio Cultural Subacuático En La Convención Sobre La Protección Del Patrimonio Cultural Subacuático De 2001. Rev. Derecho-Univ. Católica Del Norte 2017, 24, 247–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, S.G. Miranda Gonçalves, R. El régimen jurídico del patrimonio cultural subacuático. Especial referencia al ordenamiento jurídico español. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch. Gladius Scientia. Revista de Seguridad del CESEG 2020, 2, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the Records of the General Conference: 31st Session, Paris, France, 15 October–3 November 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera, A.; Alfonso, C.; Auriemma, R.; Di Bartolo, M. Monitoring and Conservation of Archaeological Wooden Elements from Ship Wrecks Using 3D Digital Imaging. In Proceedings of the 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHeritage), Marseille, France, 28 October–1 November 2013; Volume 1, pp. 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, M. Stakes and Challenges for Underwater Cultural Heritage in the Era of Blue Growth and the Role of Spatial Planning: Implications and Prospects in Greece. Heritage 2019, 2, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on International Principles Applicable to Archaeological Excavations; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Cousteau, J.Y.; Gagnan, E. Diving Unit. U.S. Patent US2485039A, 18 October 1949. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US2485039A/en (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Tusa, S. Mirabilia Maris: Tesori dai Mari di Sicilia; Agneto, F., Ed.; Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei beni Culturali e Dell’identità siciliana, Dipartimento dei beni Culturali e Dell’identità Siciliana: Palermo, Italy, 2016; ISBN 978-88-6164-430-4. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. UNCLOS III, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Law of the Sea Treaty); United Nations: Montego Bay, Jamaica, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- International Committee for the Management of Archaeological Heritage (ICAHM). Charter for the Protection and Management of the Archaeological Heritage; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1992; Volume 143. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Charter on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Università di Milano “Bicocca” (Dipartimento Giuridico delle Istituzioni Nazionali ed Europee); Regione Siciliana (Assesorato dei Beni Culturali ed Ambientali e della Pubblica Istruzione); Università degli Studi di Palermo, Facoltà di Economia (Istituto di Diritto del Lavoro e della Navigazione). Syracuse Declaration on the Submarine Cultural Heritage of the Mediterranean Sea. In Proceedings of the Conference “Strumenti per la Protezione del Patrimonio Culturale Marino nel Mediterraneo”, Palermo—Siracusa, Italy, 8–10 March 2001. [Google Scholar]

- The Member States of the Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (CETS No. 199); Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Capulli, M. Il patrimonio culturale sommerso. Ricerche e proposte per il futuro dell’archeologia subacquea in Italia; Forum Edizioni: Udine, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-88-328-3112-2. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN General Assembly. Protection of the Coastal and Marine Environment; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1988; Vol. Resolution n 17.38. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN General Assembly. Marine and Coastal Area Conservation; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1994; Vol. Resolution n 19.46. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher, G. Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK,, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Regional Seas Programme. Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Protocol Concerning Mediterranean Specially Protected Areas; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization Assembly. Revised Guidelines for the Identification and Designation of Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2005; Vol. Resolution A.982(24). [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, O. Beni Culturali. In Enciclopedia del Novecento; II Supplemento; Treccani: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Alibrandi, T. Beni Culturali e Ambientali. In Enciclopedia Giuridica; Treccani: Rome, Italy, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe. Council of Europe Landscape Convention; The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Westerdahl, C. The Maritime Cultural Landscape. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 1992, 21, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manacorda, D. Il Sito Archeologico: Fra Ricerca e Valorizzazione; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatori, M. Archeologia sommersa nel Mediterraneo; Restauro Consolidamento; Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane: Napoli, Italy, 2010; ISBN 978-88-495-2080-4. [Google Scholar]

- Antonioli, F.; Leoni, G. Holocene sea level rise research using archaeological site (Siti archeologici sommersi e loro utilizzazione quali indicatori per lo studio delle variazioni recenti del livello del mare). Ital. J. Quat. Sci. 1998, 11, 122–139. [Google Scholar]

- Felici, E. La Ricerca Sui Porti Romani in Cementizio: Metodi e Obiettivi. In Proceedings of the VIII Ciclo di Lezioni sulla Ricerca Applicata in Archeologia: Archeologia Subacquea, Come Opera l’archeologo Sott’acqua. Storie dalle acque; Volpe, G., Ed.; All’insegna del Giglio, Sesto Fiorentino: Florence, Italy, 1998; pp. 275–340. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, J.; Rovere, A.; Fontana, A.; Furlani, S.; Vacchi, M.; Inglis, R.H.; Galili, E.; Antonioli, F.; Sivan, D.; Miko, S.; et al. Late Quaternary Sea-Level Changes and Early Human Societies in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean Basin: An Interdisciplinary Review. Quat. Int. 2017, 449, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeck, K.; Antonioli, F.; Purcell, A.; Silenzi, S. Sea-Level Change along the Italian Coast for the Past 10,000 yr. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2004, 23, 1567–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeck, K.; Purcell, A. Sea-Level Change in the Mediterranean Sea since the LGM: Model Predictions for Tectonically Stable Areas. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2005, 24, 1969–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, U.; Russo, F. Il Bradisismo Dei Campi Flegrei: Dati Geomorfologici Ed Evidenze Archeologiche. In Forma Maris; Gianfrotta, P.A., Maniscalco, F., Eds.; Massa Editore: Neaples, Italy, 2001; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, P. Estetica e Paesaggio; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-88-15-13234-5. [Google Scholar]

- Assemblea Regionale Siciliana. Legge Finanziaria della Regione Siciliana per L’anno 2004 (Sicily Regional Law 29/12/2003 no.21); Gazzetta Ufficiale della Regione Siciliana: Palermo, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Understanding the Politics of Heritage; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-7190-8152-1. [Google Scholar]

- Federici, C. Un Selfie Pagato a Caro Prezzo; Il Manifesto: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).