‘Your’s Truly’: The Creation and Consumption of Commercial Tourist Portraits

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Early Destination Photography

1.2. Early Tourist Portraits

1.3. Postcard Production

1.4. Real Photo Postcards

2. Methodology

3. Examples of Tourist Photography

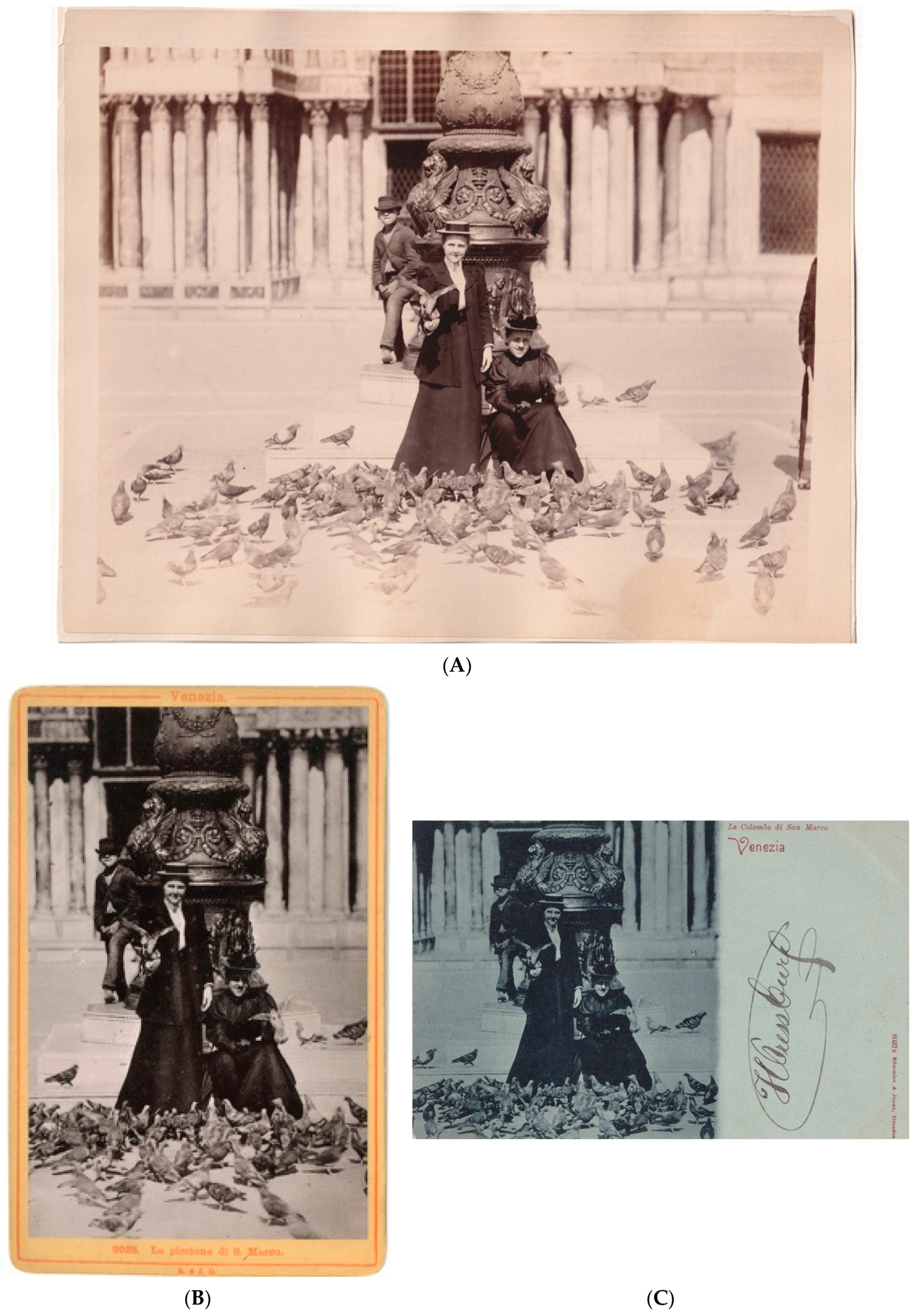

3.1. Example 1: Venice

3.1.1. Context

‘A large flock of pigeons enlivens the Piazza. In accordance with an old custom, pigeons were sent out from the vestibule of San Marco on Palm Sunday, and these nested in the nooks and crannies of the surrounding buildings. Down to the close of the republic they were fed at public expense, but they are now dependent on private charity. Towards evening they perch in great numbers under the arches of Saint Mark’s.’ [59].

‘Grain and peas may be bought for the pigeons from various loungers in the Piazza, and those whose ambition leans in that direction may have themselves photographed with the pigeons clustering round them’ [60].

3.1.2. Production and Consumption of Tourist Photography in Venice

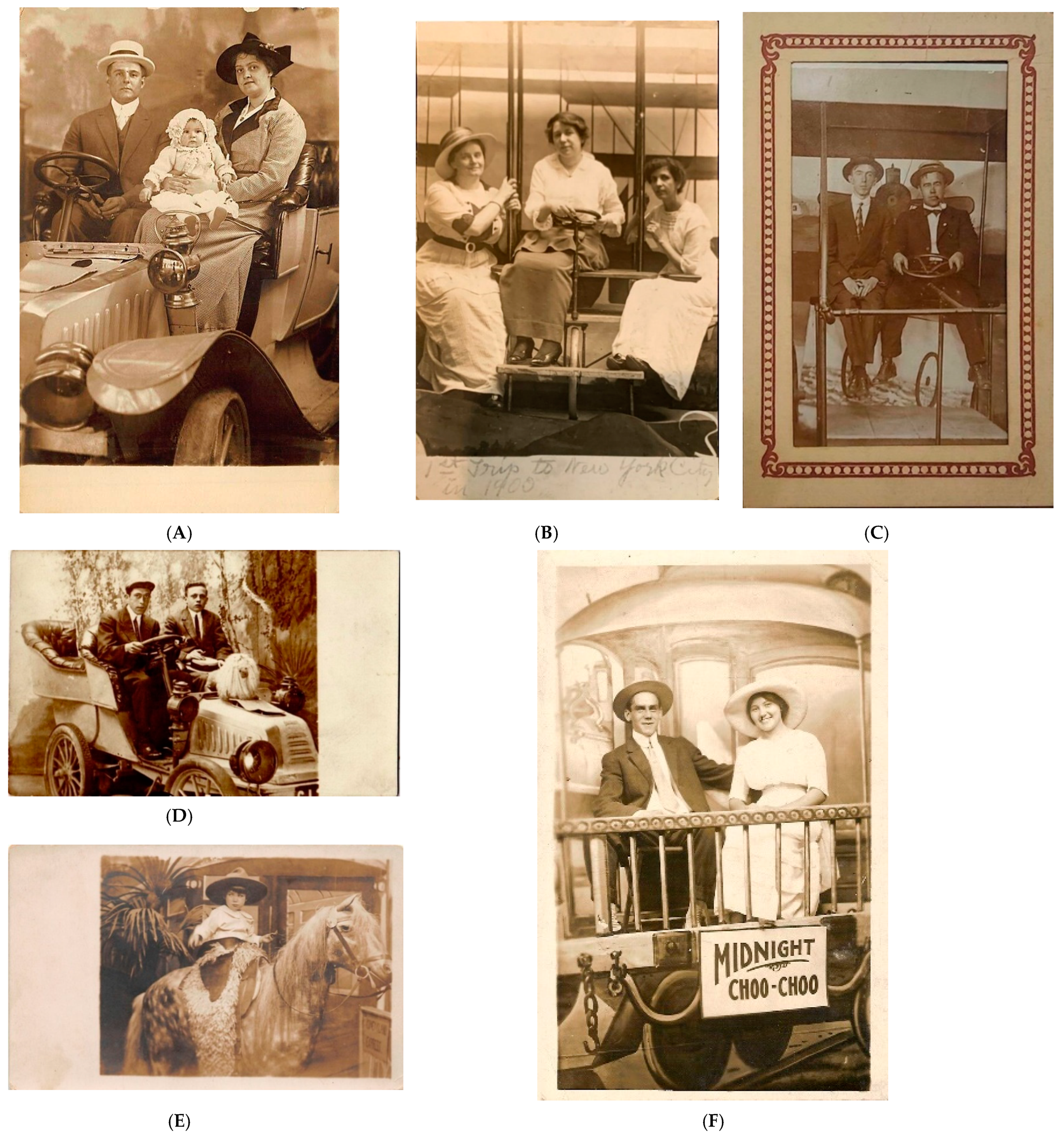

3.2. Example 2: Ostrich Farms in California

3.2.1. Context

3.2.2. Production and Consumption of Tourist Photography in California

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Höckert, E.; Lüthje, M.; Ilola, H.; Stewart, E. Gazes and faces in tourist photography. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarles, C. The photographed other: Interplays of agency in tourist photography in Cusco, Peru. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 928–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, I.S.; McKercher, B.; Lo, A.; Cheung, C.; Law, R. Tourism and online photography. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.; Yeh, J.H.Y. Tourist photographs: Signs of self. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 5, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. Staging tourism: Tourists as performers. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeye, P.C.; Crompton, J.L. Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the Lower Rio Grande Valley. J. Travel Res. 1991, 30, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G.; Garcı́a, H.C. Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, K.J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. An exploration of cross-cultural destination image assessment. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, O.H. Photography and travel brochures: The circle of representation. Tour. Geogr. 2003, 5, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, H.I. Staging ‘Koreana’ for the Tourist Gaze: Imperialist Nostalgia and the Circulation of Picture Postcards. Hist. Photogr. 2013, 37, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkery, C.K.; Bailey, A.J. Lobster is big in Boston: Postcards, place commodification, and tourism. GeoJournal 1994, 34, 491–498. [Google Scholar]

- Jimura, T.; Lee, T.J. The impact of photographs on the online marketing for tourism: The case of Japanese-style inns. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon that image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martin, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo, P.; Moreno-Gil, S. Analysis of the projected image of tourism destinations on photographs: A literature review to prepare for the future. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B. Understanding the relationship between tourism destination imagery and tourist photography. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, A. Tourist photography and the reverse gaze. Ethos 2006, 34, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky-Porges, E. The grand tour travel as an educational device 1600–1800. Ann. Tour. Res. 1981, 8, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, J. The grand tour: A key phase in the history of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1985, 12, 297–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeman, C.K. Tischbein’s Anna Amalia, Duchess of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach: Friendship, Sociability, and “Heimat” In Eighteenth-Century Naples. Source Notes Hist. Art 2013, 33, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowron, E.P.; Kerber, P.B. Pompeo Batoni: Prince of Painters in Eighteenth-Century Rome; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- West, S. Gender and internationalism: The case of Rosalba Carriera. In Italian Culture in Northern Europe in the Eighteenth Century; West, S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- Haldrup, M.; Larsen, J. The family gaze. Tour. Stud. 2003, 3, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, K.N. Sublime Vistas and Scenic Backdrops: Nineteenth-Century Painters and Photographers at Yosemite. Calif. Hist. 1990, 69, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, L.J. Cartes de visite and the first mass media photographic images of the English judiciary: Continuity and change. In Judgment in the Victorian Age; Gregory, J., Grey, D.J.R., Bautz, A., Eds.; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, M. Postcards from Tahiti: Picturing France’s colonial agendas, yesterday and today. In Cultures through the Post: Essays on Tourism and Postcards; Morgan, N., Robinson, M., Eds.; Channel View: Clevedon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, M. Tahiti intertwined: Ancestral land, tourist postcard, and nuclear test site. Am. Anthropol. 2000, 102, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, D. Fantasia of the phototheque: French postcard views of colonial Senegal. Afr. Arts 1991, 24, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanchi, M. Postcards from the colonies: Are postcards valuable as historical evidence? Ozhistorybytes 2004, 4, 541. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, J. Postcards from the Edge of Empire: Images and messages from French Indochina. SPAFA J. 2008, 18, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, P. Six postcards from Arabia: A visual discourse of colonial travels in the Orient. Tour. Stud. 2004, 4, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderwood, P.J. The Picture Postcard as Historical Evidence: Veracruz, 1914. Americas 1988, 45, 201–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Imagery of Postcards sold in Micronesia during the German Colonial Period. Micron. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2006, 5, 345–374. [Google Scholar]

- Wehbe, R. Seeing Beirut through Colonial Postcards: A Charged Reality; Department of Architecture and Design: Beirut, Lebanon, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, D. Thinking postcards. Vis. Resour. 2001, 17, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, H.R. Ohio in Historic Postcards: Self-Portrait of a State; Kent State University Press: Kent, OH, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, C. Railways of Latin America in Historic Postcards: Featuring South and Central America, the Caribbean and the West Indies; Trackside Publications: Bacchus Marsh, VIC, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Man, T.C.; Toong, D.P.; Cheung, A.S.; Kai, M.Y. A Selective Collection of Hong Kong Historic Postcards; Joint Publishing (HK) Co., Ltd.: Hong Kong, China, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J. Moments in Time: A Book of Australian Postcards; National Library of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrul, G.; Krieck, M. Schwerin auf Historischen Ansichtskarten: Altstadt: Schwerin in den Grenzen von 1884; Edition Digital: Pinnow, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arreola, D.D.; Burkhart, N. Photographic postcards and visual urban landscape. Urban Geogr. 2010, 31, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, B. An entangled object: The picture postcard as souvenir and collectible, exchange and ritual communication. Cult. Anal. 2005, 4, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. “A Startling Impression of Orderly Picturesqueness.” A Visual Data Set of American Fan Palms (Washingtonia spp.) Depicted on Early Twentieth Century Postcards; Institute for Land, Water and Society Report; Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University: Albury, NSW, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The evidentiary value of late nineteenth and early twentieth century postcards for heritage studies. Heritage 2021, 4, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkin, N. Cartomania and the Scriptive Album: Cartes-de-Visite as Objects of Social Practice. In Performing Objects and Theatrical Things; Schweitzer, M., Zerdy, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Material Culture of the German Nuclear Industry II: Picture Postcards and QSL Cards; Institute for Land, Water and Society Report 150; Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University: Albury, NSW, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. QSL: Subliminal messaging by the Nuclear Industry in Germany during the 1980s. Heritage 2021, 4, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, E.J.; Snowden Ward, H. The Photographic Picture Post-Card: For Personal Use and for Profit, 2nd ed.; Dawbarn & Ward: London, UK, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, J.A. Photographic Post-Cards. Photo Miniat. 1908, 8, 425–428. [Google Scholar]

- Kipping, M.; Wadhwani, R.D.; Bucheli, M. Analyzing and interpreting historical sources: A basic methodology. Organ. Time Hist. Theory Methods 2014, 305–329. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, I. Understanding Material Culture; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels, L.; Mannay, D. The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrink, J. Why the innocents went abroad: Mark Twain and American tourism in the late nineteenth century. Am. Lit. Realism 1983, 1870–1910, 278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Stowe, W.W. Going Abroad: European Travel in Nineteenth-Century American Culture; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Der Palmsonntag, die Markustauben, der Charfreitag und Ostersonntag zu Venedig. Echo. Z. für Lit. Kunst Und Leben Ital. 1838, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Baedeker, K. Italy. Northern Italy as far as Leghorn, Florene and Ancona, and the island of Corsica. In Handbook for Travellers, 1st ed.; Karl Baedeker: Coblenz, Germany, 1867. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, F. Ein Mittag auf dem Marcusthurm zu Venedig. In Die Gartenlaube; Ernst Keil’s Nachfolger: Leipzig, Germany, 1866; pp. 340–343. [Google Scholar]

- Baedeker, K. Italy. First Part, Northern Italy Including Leghorn, Florene and Ravenna, and the Island of Corsica, 8th ed.; Karl Baedeker: Leipzig, Germany, 1889. [Google Scholar]

- Baedeker, K. Italy. First Part, Northern Italy including Leghorn, Florene and Ravenna, 10th ed.; Karl Baedeker: Leipzig, Germany; London, UK, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Getty Museum. Studio Portait of Beth D. Kimberly Taken by Giovanni Contarini (ca 1890). Available online: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/89304/giovanni-contarini-beth-d-kimberly-italian-about-1890/?artview=dor550324 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Getty Museum. Studio Portait of Ms Chester Taken by Giovanni Contarini (ca 1890). Available online: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/miss-chester-giovanni-contarini/bgGE86Mcy4T21A?hl=en (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Dwyer, J.F. In Europe—Now. Call 1922, 24, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Swadling, P. Plumes from Paradise: Trade Cycles in Outer Southeast Asia and Their Impact on New Guinea and Nearby Islands Until 1920; Papua New Guinea National Museum in Association with Robert Brown & Associates: Coorparoo, DC, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Excessive exploitation of Pacific seabird populations at the turn of the 20th century. Mar. Ornithol. 1998, 29, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Exploitation of bird plumages in the German Mariana Islands. Micronesica 1999, 31, 309–318. [Google Scholar]

- De Mosenthal, J.; Harting, J.E. Ostriches and Ostrich Farming; Trübner & Company: London, UK, 1877. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, M.; Farrell, D. A history of ostrich farming–Its potential in Australian agriculture. Recent Adv. Anim. Nutr. Aust. 1991, 1991, 292–297. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass, A. Ostrich-farming. S. Afr. J. Sci. 1905, 3, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Doughty, R. Ostrich farming American style. Agric. Hist. 1973, 47, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.R. The Ostrich Industry in the United States; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Cawston, E. Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Souvenir Catalogue and Feather Price List; Cawston Ostrich Farm: South Pasadena, CA, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Cawston, E.; Fox, C.E. Ostriches and Ostrich Farming in California; Washington Garden Ostrich Farm: Washington, DC, USA, 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Cawston, E. Ostrich Farming in California; Norwalk Ostrich Farm: Norwalk, CT, USA, 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Beyelia, N. For the Birds: Edwin Cawston and the Farm That Invigorated Los Angeles. In Los Angeles Public Library Blog; Arcadia Publishing: Mount Pleasant, CA, USA, 2019; Volume 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Willey, D.A. Raising Ostriches in the United States. Sci. Am. 1904, 90, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Florida Ostrich Farm. The Florida Ostrich Farm. In Florida Ostrich Farm; Florida Ostrich Farm: Jacksonville, FL, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Riding and Driving Big Bird: A Photographic Documentation of Commercial Tourist Portraits at Ostrich Farms in the USA; Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University: Albury, NSW, Australia, 2021; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Markwick, M. Postcards from Malta. Image, Consumption, Context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotterrer, S.; Cranz, G. The picture postcard: Its development and role in American urbanization. J. Am. Cult. 1982, 5, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S. A Murmur of Small Voices: On the Picture Postcard in Academic Research. Archivaria 2006, 60, 167–184. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spennemann, D.H.R. ‘Your’s Truly’: The Creation and Consumption of Commercial Tourist Portraits. Heritage 2021, 4, 3257-3287. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040182

Spennemann DHR. ‘Your’s Truly’: The Creation and Consumption of Commercial Tourist Portraits. Heritage. 2021; 4(4):3257-3287. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040182

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpennemann, Dirk H. R. 2021. "‘Your’s Truly’: The Creation and Consumption of Commercial Tourist Portraits" Heritage 4, no. 4: 3257-3287. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040182

APA StyleSpennemann, D. H. R. (2021). ‘Your’s Truly’: The Creation and Consumption of Commercial Tourist Portraits. Heritage, 4(4), 3257-3287. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040182