1. Introduction

For years, many Japanese people have been showing a strong interest in time travel or, as called by the Japanese, time-slip-themed entertainment. This hype began in 1994, when a local television drama called Bakumatsu Kokosei introduced a story about a high school teacher and her students who accidentally travelled to the Edo period (1603−1868). Due to its popularity, the drama series was remade into a movie in 2014. Later, many television dramas were produced with a similar time-slip story to different historical periods. Alongside drama, other forms of entertainment such as games and animation have also been created to entertain those who enjoy the time-slip-themed story.

The growth of time-slip-themed entertainment appeared to contribute to the rise of young Japanese people’s interest in their history [

1]. In 2010, media reported the surge of

rekijo, or female history buffs, in Japan [

2]. Rekijo is a subset of Japan’s otaku, showing a more specific interest in the Japanese history genre. The fans are usually attracted to and fantasize about men from the past [

3]. Their interest in historical objects and heritage sites is deeply influenced by historical dramas, movies, and games [

4]. In recent years, these female fans began to flock into castles, battle sites, museums, and old bookstores across Japan to fulfil their fantasies on certain historical figures or events [

1]. Apparently, their pilgrimages have stimulated the growth of heritage tourism in various Buddhist shrines and Shinto temples [

4]. Responding to this, many regional cities and towns began to promote their historical assets to cater for the growing demand for fantasy-themed heritage tourism. Several places even created an artificial place where people can experience specific Japanese historical periods, such as Edo Period (1603–1868)-themed Edo Wonderland Park in Tochigi Prefecture and Showa Period (1926–1989)-themed Seibu Yuenchi Park in Saitama Prefecture.

Riding on the popularity of time-slip-themed entertainment, Aomori Prefecture has adopted a similar theme to promote prefectural tourism. The prefecture is famous for having numerous assets remaining from Jomon, the prehistorical period of Japan. Utilizing the historical and cultural assets from the Jomon Period, Aomori began to brand itself as a place where people can experience a time-travel journey. This paper aims to investigate the practice of Aomori to incorporate fantasy in its heritage tourism. It specifically explores Aomori’s strategy to promote its prehistorical assets using a specific fantasy theme and certain historical period. The paper begins with a literature review discussing heritage tourism, including the adoption of fantasy elements to promote a destination. After this, the paper introduces the prehistorical assets in Aomori Prefecture, Japan, and describes the methodology to retrieve the primary data. Following this, the research result and discussion on the findings related to Aomori’s practice to promote its heritage tourism are presented.

2. Heritage, Fantasy, and Tourism

Since the classical period, people have been visiting places with historical significance [

5]. Gyr added that ancient sites and relics were the objects that the classical leaders went to see for leisure [

5]. The practice of visiting heritage sites continued in the medieval period. However, leisure activities no longer dominated as the purpose of travel as people were more attracted to engage in spiritual pilgrimage [

6]. Through The Pilgrim of Bordeaux, a record about Christian Pilgrimage in the year 333, we learned about the attraction of religious heritage and sacred sites for the people in the past [

7]. While spiritual pilgrimage was still common in later periods, another trend emerged with people’s growing interest in arts and humanities [

8]. The Renaissance period brought back people’s great interest in ancient sites and old buildings. The Grand Tour established in the 18th century empowered many young aristocrats to travel to many places and observe cultural heritage situated within European continents, such as the Greco-Roman antiquity and the classical Baroque tradition [

9].

Even now, heritage is still the primary resource for tourism. People still travel to places with historical landmarks that pose significant value, such as archaeological sites, historical monuments, and old districts. The Historic Preservation of Georgia defines this personal encounter with a community’s traditions, history, and culture as heritage tourism [

10]. This definition is in line with Yan [

11], who asserted that heritage tourism is a form of special tourism that offers opportunities to look at the past in the present. Hence, heritage tourism also includes some activities tied to myth-making and stories to deliver certain messages about the place associations embedded in the local community [

12]. Therefore, heritage assets need to be preserved to enable such content creation. Indeed, heritage assets are very helpful for tourism since they are a zero-cost, freely accessible, flexible, and inexhaustible resource [

13]. From the current practice of utilizing heritage for tourism, seemingly there are two types of heritage tourism [

14,

15]. First is tourism that focuses on material components of culture and heritage, including both tangible and intangible heritage. Second is the type of tourism that enables tourists to experience something from their consumption of heritage resources.

Several studies have identified some factors behind tourists’ motivation to engage in heritage tourism, including personal relevance [

16], a quest for authenticity [

17], and nostalgic feeling [

18]. Some cities have deliberately used heritage to stimulate nostalgia and invite visitors to construct an interpretation that is sometimes more dominated by fantasy rather than truth [

19,

20]. According to Stern (1992), nostalgia can be categorized into (i) the historical nostalgia, which refers to a sentimental attachment to historical stories of the good old days before people were born, and (ii) personal nostalgia, which implies the beautified memories of moments that people actually experienced and the sentimental feelings of never being able to return to that period [

21]. Many cities began to utilize this nostalgic feeling and transform the selected elements of history into a romantic and idyllic past to cater to people’s fantasy, even though sometimes, the practice covered the former contradictions, struggles, and conflicts [

22].

Through the romanticization of the past, cities may attract postmodern visitors looking for imaginary and fantasy-related activities [

23,

24]. Tourists always have their imagination, and naturally they will pursue authenticity when travelling to a particular place [

25]. In this travelling adventure, fantasy can be offered to tourists with desires, dreams, or magical expectations to satisfy their individual needs [

26]. The historical objects might attract tourists as they contain collective memories throughout the years that offer narrative stories and legends for people to fantasize about [

27,

28]. A study by Kallen in 2012 [

29] further overviewed the use of a time-travel theme in the Hintang Laos archaeological site to attract tourism. She further underlined that selling a time-travel theme has become more common in heritage marketing, especially in western countries. The study of Lovell verified that a specific historic environment could offer an imaginative environment that fulfils people’s fantasies, including the fantasy to travel to the past, or live in one particular historical period [

30].

Cusack confirmed that the historic environment could be the source of inspiration for people’s creative works, such as novels and movies [

23]. Interestingly, the latest trend showed that featuring heritage in pop culture can induce another form of tourism, such as film-induced tourism or contents tourism [

31,

32]. Seaton specifically highlighted the ability of Japanese historical drama series to induce tourism in the backdrop cities such as Hakodate, Kochi, Hino, and Kyoto [

33]. The Japanese scholars further discussed the contribution of fans and the local subculture to generate such fantasy-led heritage tourism in Japan [

4,

34]. Sugawa-Shimada specifically explored how the historical-themed games, novels, animation, and comics could stir up Japanese girls’ fantasy and produce a sense of attachment to the historical objects featured in those creative works [

4]. The behaviors of these fangirls to visit Japanese castles and immerse themselves in the idealized past confirmed the work of Lovell [

30], who asserted that a historic environment could empower people to discover heritage marvelous or magi-heritage in the actual world.

When such an environment is unavailable, business sectors often create fake historic architecture to mimic specific historical periods and attract tourism [

35,

36]. Levi further identified that the combination of fake historical buildings, the historical buildings, and contemporary architecture could create a sense of history in the region and bring economic vitality [

36]. However, Levi also warned about the danger that lies within creating fake historic buildings in the city. It might reduce the priority for preserving the real architecture and increase the likelihood of creating generic global products that threaten the real character of the historic area [

36,

37]. Nonetheless, Levi’s study revealed how tourists prefer to see fake historic buildings to contemporary buildings [

36]. This finding verified Lovell’s statement again about the attractiveness of the historic environment for modern people [

30].

For centuries, people’s interest in the historic environment and the heritage sector has helped cities flourish economically [

38]. A study by McGrath revealed the direct financial contributions in Pennsylvania communities, including the creation of 19,333 jobs, USD 477.8 million in labor income, and USD 709 million in value-added effects [

39]. The heritage sector has also supported the UK’s economy, providing 563,509 jobs and attracting 215 million tourists in 2019 [

40].

However, in some cases, tourism could have a negative impact on the heritage, especially the archaeological sites. Archaeology has had a contradictory relationship with tourism since long ago [

41]. A case from Petra demonstrated how mass tourism has slowly destroyed archaeological materials [

42]. In the same vein, Hugo identified the negative impact of overtourism on Machu Picchu and the Old City of Jerusalem and its walls [

43]. These impacts include (i) the structural impact, such as from vandalism, litter, theft, degradation, and erosion, and (ii) the cultural impact, such as from cultural appropriation, loss of traditions, and adjustment on societal norms. Nevertheless, studies identified that overtourism is not the only issue faced by the archaeological sites. Several sites have experienced the opposite problem, which is undertourism, or the undervisiting of tourist destinations [

44]. There are numerous undervisited tourist destination places worldwide, often not equipped with proper tourism infrastructure or with an integrated management plan [

45,

46]. Whenever heritage destinations lack attractive elements, it is challenging to invite the younger generation to engage in heritage tourism [

47], including archaeological tourism, as few people visit such places only for archaeological reasons [

41]. One way to increase people’s interest in those places is to integrate the visits with other destinations situated in the nearby area [

41].

3. Aomori and Its Jomon Prehistoric Assets

This study focuses on Aomori, a prefecture situated in the northern part of Japanese main island Honshu. As of 2021, this region is inhabited by 1,216,448 residents [

48]. The Vox Populi identified Aomori as the third-fastest shrinking prefecture in Japan, facing severe depopulation [

49]. Henceforth, the prefecture is participating in the national government’s regional revitalization plan by promoting its tourism aggressively to the general public. Tourism is considered one of the most effective approaches to revitalize the economy and repopulate Japanese outlying areas. Thus, Aomori has promoted various tourism resources to attract outsiders, for instance, boosting its apple products. The history of Aomori’s apple dates back to 1876 when the local Japanese were introduced to the apple trees for the first time. Later, the prefecture became famous for its apple and began to develop apple-based tourism. Nevertheless, the discovery of Sannai-Maruyama, the largest Jomon settlement in Japan, in 1992 turned the Japanese media and public’s attention to Aomori’s prehistorical assets [

50]. The site was firstly excavated by the prefectural board of education, which had the prior intention to construct a baseball stadium [

51]. The excavation unearthed pit buildings, pillar-supported buildings, many pot shards, stone tools, lacquered objects, clay figurines, jade, and obsidian [

52]. Soon, people began to flock to Aomori to see the remains of Jomon civilization, a phenomenon that Habu [

50] described as the Sannai-Maruyama fever. This tourism hype encouraged the prefectural government to declare Aomori as the destination for heritage tourism.

Before discovering Sannai-Maruyama, Japanese people focused on Yayoi and the later civilization to study the origin of Japanese people and culture [

50]. However, the discovery triggered interest back to Jomon, the ancient era when Japanese ancestors began to settle on the land. The name of Jomon was given to Japan’s late Glacial Period due to the discovery of a typical cord pattern in the pottery. Jomon people kneaded clay to produce pottery for daily use, and they created the cord pattern in their pottery products. The amount of pottery discovered in many archaeological sites suggests the behavior of Jomon as a settled rather than nomadic community. The Jomon people had several unique characteristics, including their tendency to live in large settlements and have organized subsistence strategies such as building storage pits and large shell middens [

50]. The remains from across Japan suggest that the Jomon people mastered fishing and hunting techniques. For instance, the discovery of blowfish remains and elderberry seeds at the excavation sites indicates that Jomon life was less primitive than had been assumed [

53]. The remains of a huge wooden pole discovered in the Sannai-Maruyama site verifies that Jomon was not a primitive hunter–gatherer community. Instead, they had the skills to adapt to climate and nature change [

54], for example, they produced domesticated rice, even before agriculture began in the Yayoi period. Further, the experts believe that the Jomon people had a sustainable life and were a peaceful and harmonious society as their settlements had no defensive walls or barriers [

54].

The remnants from Jomon Civilization have mostly been discovered in Hokkaido and the Northern Tohoku region of Japan. Compared with other regions in Japan, the archaeological sites discovered in these regions are larger, and their locations signify a concentration of Jomon settlement in Japan’s northern region. The largest and most significant site is Sannai-Maruyama in Aomori City. This site was registered as a national historic site in March 1997 and was granted the status of world cultural heritage site in 2021. Not far from this site, archaeologists discovered another site remaining from Jomon civilization, named Komakino Stone Circle. This site comprises flat stones aligned alternately in longitudinal and latitudinal directions [

52]. The discovery of the two sites in Aomori City signified its importance in developing Jomon Civilization in Japan.

Several archaeological sites were also discovered outside Aomori City, such as in Tsugaru City, Sotogahama Town, Hirosaki City, Shichinohe Town, and Hachinohe City (See

Figure 1). The Odai Yamamoto Site in Sotogahama Town is where the oldest pottery in Japan was excavated. This discovery provided early evidence of the Jomon People’s intention to form more permanent settlements. Meanwhile, the Kamegaoka Burial Site in Tsugaru City provided primary evidence on the Jomon people’s spirituality. The discovery of these sites verified the status of Aomori as one of the prefectures with the most extensive collections from Jomon culture.

5. Jomon Fantasy: A Time-Slip Journey to the Jomon Period

This section explores the incorporation of fantasy in Aomori’s heritage tourism. It begins by introducing the three heritage tourism itineraries: Jomon Aomori Romantic Journey, Jomon Map, and Jomon Rally Stamp. Following this, we overview the approach to incorporate pop culture; in this context, Aomori’s effort to induce people’s historical nostalgia to the Jomon period through the creation of promotional and edutainment videos. Lastly, the tourism situation in Aomori before and during the COVID-19 pandemic is highlighted.

5.1. The Development of Heritage Tourism Itineraries

As mentioned above, the development of massive heritage tourism in Aomori was triggered by the discovery of Sannai-Maruyama in Aomori City in 1992. Sannai-Maruyama’s scale has attracted domestic visitors’ attention in the prehistorical assets in Aomori Prefecture and its surrounding regions. Since then, various festivals have been held on this site, such as Jomon Music Festival in 2009 and Jomon Art Festival in 2014 [

54]. Responding to this, the Secretariat of the World Cultural Heritage Registration Promotion Office of Aomori Prefectural Government that manages Jomon Japan began to design various itineraries to attract tourists to explore the prehistorical assets of the prefecture. This section overviews the latest three itineraries that promoted the time-slip experience to the Jomon Period.

5.1.1. Jomon Aomori Romantic Journey

In 2017, the World Cultural Heritage Registration Promotion Office of the Department of Policy and Planning Japan introduced Aomori Jomon Romantic Journey (AJRJ) to the public. It was repromoted in 2021 along with the creation of the Jomon Fantasy PR Movie, which is described in

Section 5.3. AJRJ is a list of heritage tourism itineraries recommended by the World Cultural Heritage Registration Promotion Office, Department of Policy and Planning. Tourists are suggested to try three different courses. The first course focuses on the exploration of Jomon assets within Aomori City. It suggests that visitors explore Sannai-Maruyama Site (see

Figure 2), followed by a short visit to the nearby modern Aomori Museum of Art. After lunch, visitors are suggested to visit Komakino Stone Circle Site and Sotogahama Oyama Furusato Shiryokan Museum. The course also promotes other sightseeing places such as local museums unrelated to Jomon theme and a souvenir station called A-Factory. A-Factory is a commercial complex comprised of a market, cafes, restaurants, and souvenir shops. The complex was built to support the prefecture’s revitalization.

The second course specifically targets women as potential customers. With the title of A travel to Hachinohe City for Women, this course clearly states its suitability for women visitors. The course suggests several activities in Hachinohe City, which is situated in the southern part of Aomori Prefecture. First, it suggests the visitors explore The Korekawa Jomon Museum, which specializes in dogu or clay figurines collections from Jomon period. The museum offers special curry rice using Japanese ancient rice or kodaimai called Jomon Curry. This type of healthy meal is very popular among Japanese young women. Other than The Korekawa Jomon Museum, visitors are also invited to visit Futatsumori Site in Shichinohe Town near Hachinohe City. This site is one of the enormous shell mounds in Tohoku region. It portrays the environmental changes experienced by Jomon People who lived near the coastal area. The course further promotes Hachinohe-Shichinohe’s famous pacific scenery and its marine products such as Hachinohe Maeoki Saba.

Meanwhile, the last course promotes the Retro Jomon and Japanese Modern Period. The visitors are invited to explore Tsugaru City, which is situated in western Aomori. Tsugaru city is home to the Kamegaoka Burial Site, a cemetery area that displays the sophisticated spirituality of the Jomon People. Archaeologists discovered the goggle-eyed clay figurines, which later became the icon of Tsugaru City. The course also introduces the giant sculpture of Syako Chan, goggle-eyed clay figurine of Jomon, in Tsugaru City. Syako Chan has been attracting domestic tourists since its installation at Kizukuri Station of Tsugaru City (see

Figure 3). In this third course, visitors are suggested to visit Kizukuri Station in person and learn about the civilization of Jomon in the nearby Jomon Residence Karuko Museum. After that, the course recommends that visitors enjoy local delicacies such as Syako-chan-themed meal sets dominated by local vegetables and Syako-chan-shaped sweets. In addition to Jomon, the course also promotes various historical buildings built during the late Edo and the beginning of Meiji.

Throughout our field observations, we came to realize that the romantic journey suggested by Jomon Japan is more likely to be a journey to discover the collective memories about Jomon and the later civilization of Japan. For instance, visitors are suggested to visit destinations where they can try hands-on activities such as wearing Jomon clothing and making Jomon tools, handicrafts, and toys. Seemingly, the romantic term used by Jomon Japan is an adoption of the artistic movement and glorification of the past that emerged during the European 18th century. Aomori might adopt the romanticization as Japanese people tend to show an interest in visiting a place with such romanticism characteristics, as signified by Ohata [

58]. Apparently, the romantic tourism suggested by Aomori does not refer to the concept of romantic connections between tourists couples or between tourists and the locals. We discovered nearly zero displays and content promoting such romance tourism in the suggested destinations. Similarly, no welcoming banner or digital display indicates that the visited destination is part of the Aomori Romantic Journey or time-slip tourism.

5.1.2. The Jomon Map

Another itinerary suggested by Jomon Japan is the Jomon Map itinerary. This map can be found online and also in the major tourism destination sites, including Sannai-Maruyama site and connecting train station (See

Figure 4). The distribution of the Jomon Map aims to promote the prehistoric sites in Northern Japan. It focuses not only on Aomori Prefecture but also on Japanese Northern Region in general, such as Hokkaido and Tohoku. It provides information about the location of Jomon prehistoric sites that the general public can visit. The map divides the exploration area into six groups. Out of six, three groups introduce the archaeological sites that are situated in Aomori Prefecture. The first group promotes the sites within Aomori and Sotogahama area, such as Sannai-Maruyama, Komakino Stone Circle Site, and Odai Yamamoto Site. Meanwhile, the second group introduces the sites in Hirosaki and Tsugaru area. The sites include Omori Katsuyama Stone Circle Site, Kamegaoka Burial Site, and Tagoyano Site. The last group promotes the sites in Hachinohe and Shichinohe area, such as Korekawa Site, Choshichiyachi Site, and Futatsumori Site.

Other than the location of the prehistoric sites, the map also introduces some food specialties and local sightseeing places in each promoted region. For instance, the map promotes Jusanko Shijimi or clam ramen unique to Hirosaki and Tsugaru area. It also suggests the visitors explore Takaoka no mori Historical Museum of Hirosaki Clan, which exhibits valuable treasures of the Hirosaki domain, also known as Tsugaru Clan. While the destinations suggested in Jomon Map are quite similar to those given in the Aomori Jomon Romantic Journey, the map promotes more local foods and historical assets situated within the prefecture. It also informs the visitors about two website services where children and more expert audiences can learn about Jomon culture. The website service for children is called Jomon Guru Guru and is only available in Japanese. This website provides interactive information for children to learn about the Jomon civilization. In addition, it introduces Monguru and friends, the cartoon characters wearing Jomon attires that are in charge of helping children understand the uniqueness of Jomon People. The approach to use an imaginary character to deliver historical content in Japan is quite common and has been adopted by historical Japanese cities such as Hamamatsu City Shizuoka Prefecture. Meanwhile, the other website, the Jomon Japan, delivers more detailed information for the general and more expert audiences. In addition, it enables the researchers and more expert audiences to learn about specific sites or artefacts before and after their visits from the online archives that store digital documents and reports from numerous researchers and research institutions. The website also provides information about Jomon-related seminars, workshops, and events for those interested in Jomon culture, including for the expert audiences.

Through the provision of animated videos, audio-guides, illustrations, replicas, interactive displays, and a set of hands-on activities, visitors are invited to imagine if they lived in Jomon Period. For example, in the Sannai-Maruyama Museum, there are some replicas of the Jomon People with various poses, such as demonstrated when cooking, hunting, planting seeds, and having a family gathering. In addition, visitors are invited to listen to the story of a day in the life of the Jomon Family through the audio storytelling feature provided by the museum. This audio guide is provided in Japanese and English. Visitors who are interested in learning more can apply for a bilingual guide service. However, in smaller places such as the Kamegaoka Burial Site, the provision of such interactive storytelling and guidance service is minimal and mostly limited to the information written in either the information or the panel boards.

5.1.3. The Jomon Rally Stamp

Japanese people have been accustomed to the rally stamp campaign for a long time. The basic idea of the rally stamp is to encourage the participants to collect a series of stamps from various places. Through the Jomon Japan project, the World Cultural Heritage Registration Promotion Office, Planning and Regulation Division, Aomori Prefectural Government, introduced the rally stamp campaign entitled Jomon Odekake in 2020

. The campaign includes 13 historical spots to visit in Aomori Prefecture (See

Table 1). Jomon Rally Stamp flyers are distributed in museums and several tourist destination sites (See

Figure 5).

As of 2021, the rally stamp is being held online to promote safer mobility. With the rise of COVID-19 infection in Japan, many rally stamp organizers have shifted to the online platform. With the use of IoT, the participants do not have to physically touch the stamp, which can prevent them from getting the virus. Henceforth, the transition to digital rally stamps can enable the participants to join the rally stamp being held from 6 June 2021 to 31 October 2021. Furthermore, those who collect all stamps have the opportunity to win several gifts such as a beef meat package, frozen tuna chunk, or preloaded stored value card.

5.2. The Utilization of Pop Culture to Promote Jomon Time-Slip Fantasy

In early 2021, Aomori Prefecture introduced an image song to promote its Jomon assets. The term image song, also known as a character song, refers to music-specific content and tone to a character from an anime, video game, and drama [

60]. Adding an image song to a creative work has become a common practice in Japan to ensure better sales. Thus, Aomori has taken a similar approach by working with Ringo Musume, a Hirosaki-based female idol group, to promote the prehistoric assets in the prefecture. The song’s title is Jomon, and its lyrics invite the listeners to imagine a romantic time-travel journey to the Jomon Period.

A snippet of the Jomon song

星の数にほど遠い昔々のこと祈りと愛に溢れたゲノムに刻まれた記憶たち

rarirarira君をrarirarira 待つよrarirararira時の風に吹かれているよheart

Jomon タイムスリップ Girl, 私よわかる?

English Translation

A long time ago, far from the number of stars, memories engraved in a genome full of prayer and love. Rarirarira, I’ll wait for you. Rarirarira, Heart is being blown by the wind of the time.

Jomon time-slip girl, it’s me. Do you recognize me?

This promotional video introduces several significant Jomon-related sightseeing sites in Aomori, such as Sannai Maruyama, Komakino Stone Circle, and The Gigantic Syako Chan Sculpture of Kizukuri Station. In the video, all members wear Jomon-themed clothing and dance to imitate the Jomon people. The song is being promoted through various platforms such as Spotify, Youtube, and Apple music. As of July 15, the video has been accessed 398,055 times on the official channel of Jomon Aomori. While in the official channel of Ringo Musume, the video has been seen 102,717 times. The viewers’ responses toward the promotional video have been primarily favorable. Some viewers wrote supportive messages to the group members and expressed their pride in having such important artefacts in the country. Others showed their interest in visiting Aomori after the pandemic ends. However, few of them questioned why such promotional video did not receive enough attention from the public. One viewer suggested that the prefectural government should make more efforts to promote the video. Other than promoting an image song, the prefecture also worked with Ringo Musume to introduce several archaeological sites through an edutainment program called Jomon Tanken Musume (Jomon Explorer Girls). Seven sites are promoted through this program, including Sannai-Maruyama Site and Korekawa Site. In each episode, the idol members explore the archaeological site, sometimes accompanied by local archaeologists and curators, and introduce the uniqueness of Jomon culture to the viewers. The idol members imitate the Jomon people’s lifestyle, such as making fire, cooking soup, and enjoying Aomori’s mountainous landscape. The contents and selection of comments shown in the videos invite the viewers to imagine living as a Jomon people in the ancient period as if they wanted to give a hint on how to engage in the Jomon Time-Slip Tourism. These edutainment videos are available in Japanese, but English subtitles are provided for foreign viewers. They can be accessed through the official Youtube channel of Jomon Aomori.

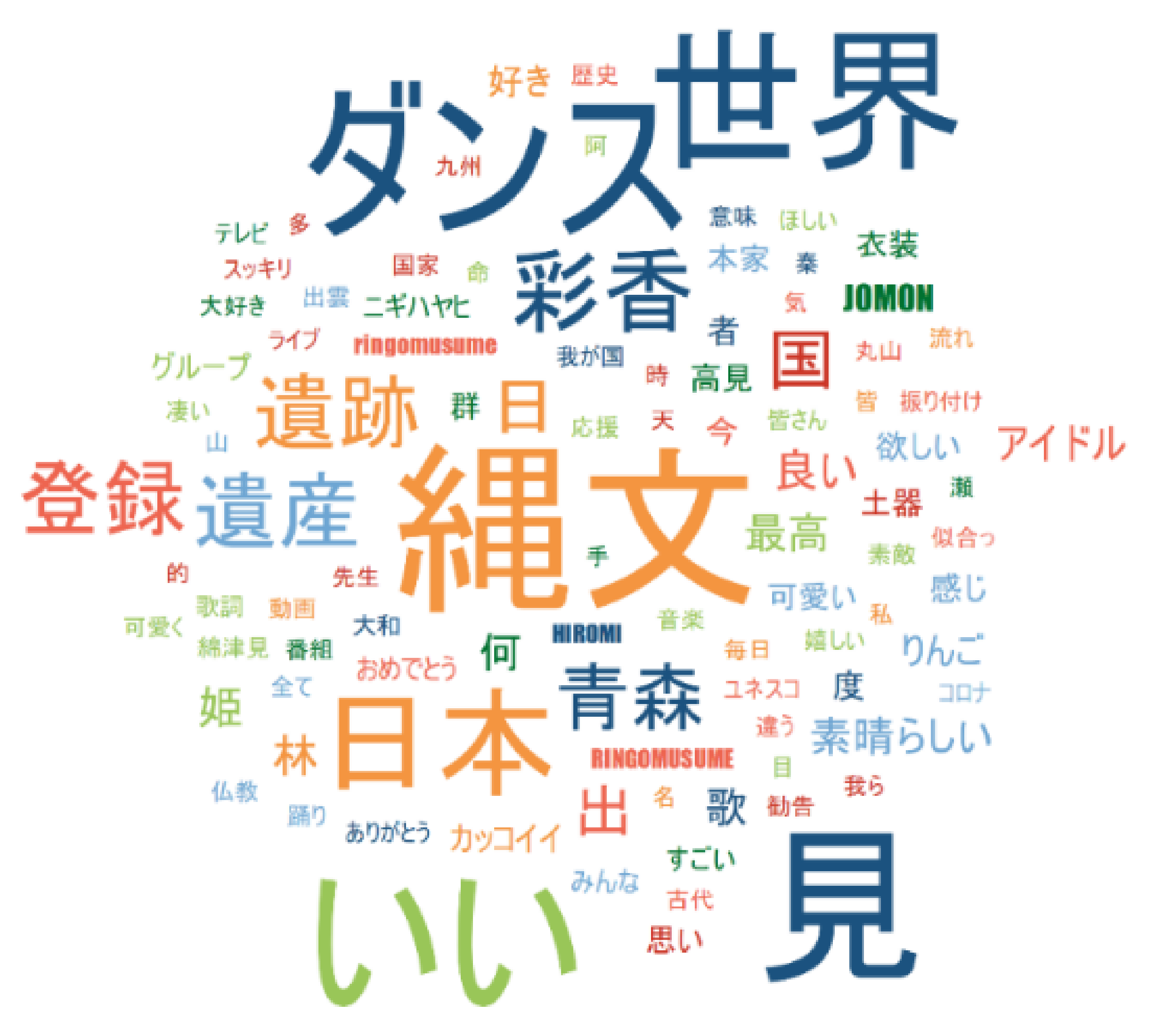

Figure 6 shows the most frequent words that appear in the comments of the viewers of Jomon Song. We analyzed the comments in Japanese using the MAXQDA word cloud function. This word cloud indicated several words that frequently appear in the viewers’ comments. The words that most commonly appear include Jomon (縄文), dance (ダンス), world (世界), see (見), good (いい), Japan (日本), heritage (遺産), ruins (遺跡), registration (登録), Ayaka (彩香), and Aomori (青森). Apparently, the promotion video (PV) has given the viewers a good impression that reminds them of the Jomon culture, its remaining sites and position in the world. Sannai Maruyama, the setting for the video clip, was recommended to be added to the World Cultural Heritage List by UNESCO advisory panel in May 2021 [

61]. Additionally, it seemed to help viewers identify Aomori as the place where people can learn about Jomon culture. The PV appeared to show the strong identity of Japan to its viewers. In addition to this, many viewers seemed to enjoy the dance shown in the PV, and they favored Ayaka, one of the Ringo Musume’s members.

5.3. Aomori Tourism before and during COVID-19

The widespread COVID-19 in Japan has affected its domestic tourism, including in Aomori, one of the prefectures relying on tourism for its regional revitalization plan. As a result, as of 6th August 2021, the prefectural government announced the official suspension of the Aomori Tourism campaign [

62]. This suspension includes the Jomon rally stamp that is scheduled to be ended on 31st August 2021. Unfortunately, there are no updated data issued by the Aomori Prefecture Tourism International Strategy Bureau that could help us identify the number of annual visitors entering Aomori in 2020 and 2021. The latest data we could retrieve were published in 2019. This data revealed the number of visitors entering Aomori from 2015 to 2019 (see

Figure 7). The average number of annual visitors from outside the prefecture is around 35,000 tourists per year [

62]. Compared to Tokyo and Kanagawa, visited by more than 20 million people per year, we could say that the number of visitors to Aomori Prefecture is relatively low [

63,

64]. Despite looking like an undertourism destination in Japan, Aomori, in fact, has ample tourism infrastructure such as accommodations, transports, and restaurants with good condition and reviews. Printed flyers and brochures about Jomon and other historical assets are available at the hotels, tourism information centers, train stations, and cultural facilities. Additionally, the prefecture provides official sites providing information about various destinations, including Jomon prehistoric assets and the access to get there.

During the spread of COVID-19, many cultural facilities are still operating, although the operation hours are reduced and stricter health protocols are imposed. Throughout our observations, we noticed that the train stations, museums, and historic sites were still kept clean and organized even when visitors declined significantly. In addition, transportation modes, such as buses, trains, and taxis, were still operating even though the frequency was less frequent than in the busiest regions, such as the Tokyo area.

Unfortunately, there are no available data that could specifically measure the impact of Jomon Fantasy’s tourism on Aomori’s economy from 2020. The latest data from Prefecture Tourism International Strategy Bureau only recorded the activity report from the year 2019. This record revealed that in 2019, tourist consumption reached 191.30 billion yen, of which 64.568 million yen was spent on accommodation expenses and around 46.8 million on souvenirs costs [

62]. This bureau data also recorded the declining number of visitations to the Sannai-Maruyama Site, from 311,879 visitors in 2018 to 202,275 visitors in 2019 [

62]. In contrast, the number of visitations to a smaller destination, such as The Korekawa Site and Museum, increased from 25,466 visitors in 2018 to 29,209 in 2019 [

62]. Despite the increase of visitors entering Aomori in 2019, it seems that they were more drawn into undertourism sites such as The Korekawa Site. Due to minimal available information, we cannot determine why such a situation happened in Aomori or whether such a case drove the prefectural government to promote the strategy to induce people’s historical nostalgia for the Jomon Period.

6. Discussion

Selling fantasy in tourism is definitely not a new topic, as discussed in the above literature review. Nevertheless, the case in Aomori sheds light on the alternative strategy to incorporate fantasy in heritage tourism. First, fantasy elements can be combined with the local popular culture to attract tourists, especially younger tourists, to consume cultural content in the targeted area. Aomori made a breakthrough approach by working with influential local figures to invite young people to immerse in a time-travel journey to the Jomon Period. While the use of a time-travel or time-slip theme in Japan has become more frequent in tourism, the involvement of J-Pop artists in promoting such heritage tourism is still uncommon. The comments of the promotional video’s viewers helped us verify the advantages of using popular idols in branding a region as the destination for experiencing a romantic time-travel fantasy. Viewers could quickly associate Aomori as the place where they can explore Jomon-related culture. The promotional video also helped them identify the significance of Sannai Maruyama, which is used as the video’s backdrop, for Japan and the world’s heritage. A similar practice to use celebrities for city branding and heritage promotion is discovered in Japan’s neighboring country, South Korea. For example, Seoul Metropolitan Government has collaborated with Kpop idols such as BTS and Seventeen to endorse their cultural heritage to young people worldwide. Throughout the pandemic, these idols have been using various ways to promote the city’s historical resources, such as using the Gyeongbokgung Royal Palace and another old palace as the music video backdrop, wearing traditional outfits during their performance, and even introducing the city’s cultural districts to the viewers. This phenomenon supported Glover, who asserted the potential influence of celebrity endorsers on aspects of the destination image [

65]. She stated that these celebrities could bring the message and evoke particular positive feelings towards the country as a tourism destination. Moreover, the promotional video is accompanied by a series of edutainment videos about Jomon people and their culture. Aksakal [

66] has underlined the advantages of edutainment for young people. The combination of learning activities and entertainment could enable the younger generations to learn new things enjoyably. Henceforth, the creation of Jomon Tanken Musume can be considered a good practice as it allows young people to visualize Jomon civilization through the edutainment content offered by the local celebrities.

Second, Aomori case validates the possibility to introduce thematic fantasy in heritage tourism. The time-slip theme chosen by Aomori enables the prefecture to offer courses and stimulate historical nostalgia for the generation who have never experienced living in the Jomon Period. It allows the visitors to see the archaeological sites and combine their visit with a quick day trip to the contemporary attractions, an integration strategy recommended by Bazan-Oehmichen [

41] when dealing with archaeotourism. Additionally, the mixture of the past and present landscapes could help the visitors compare the civilizations and construct their perception of history. Evoking people’s historical nostalgia is one of the recommended strategies in marketing, as having a higher level of nostalgia can influence consumers’ attitude toward a brand and their purchase intention [

67]. This strategy might work well in Japan, as the country has shown great interest in nostalgic marketing, for both historical and personal nostalgia. Japanese society uses the term “retro” to define the production of spaces or products that can evoke nostalgic feelings, whether historical or personal nostalgia. This term was first used in the advertising industry and was then adopted into more diverse industries [

68]. The operation of the Takimikoji in Osaka Umeda-Sky Building and Shin-Yokohama Ramen Museum in 1994 marked the beginning of fake historical retro theme park production to evoke historical and personal nostalgia in Japan [

69]. Since them, the production of such retro places has arisen across the country. Some stand alone, while others are combined with the real preserved buildings and contemporary architecture. Aomori adopted the last approach, which is combining the archaeological sites with the fake historic sites, such as the Giant Syako Chan Sculpture in Kizukuri Station, and the contemporary buildings, such as Aomori Museum of Art. By combining such a space combination, Aomori offers tourists a place similar to Hannigan’s Fantasy City [

24]. This place is usually aggressively branded and theme-o-centric. The theme enhancement, traditionally connected to a specific geographic location, historical period, or type of cultural activity, is often displayed in the environment of the fantasy city. Indeed, this kind of city is attractive for tourists interested in looking for an imaginative journey or something to fulfil their fantasy. Moreover, tourists could choose to experience the time-slip experience by following a romantic itinerary such as the Jomon Aomori Romantic Journey, or more comprehensive ones such as the Jomon Map, or one with a more active style, such as the Jomon Rally Stamp.

However further research is needed to determine whether this thematic tourism will attract foreign tourists to explore Aomori. While the previous studies signified the motivation of many foreign tourists to consume Japanese popular culture [

70,

71], the local tourism initiatives might fail to help foreign visitors find the exact images they had in mind about Japanese pop culture [

71]. Therefore, if Aomori intends to attract foreign visitors, especially pop culture fans, they would need to consider the process of intercultural appropriation by foreign fans that Sabre [

71] argued as the important factor behind their motivation to come to Japan.

Overall, Aomori presents a quite well prepared region to welcome tourists who are seeking for the combination of fantasy and heritage tourism. The tourism infrastructure, such as the facilities and services, to enable visitors to enjoy the proposed sites is available, and mostly in a good condition. The combination of visual and written communication both on sites and online enables visitors from beginner to expert levels to explore Jomon’s prehistorical assets in the itineraries that suit them the most. While the current itineraries seem to focus on domestic tourists, there is English information in most major Jomon-related sites, even though the information is quite basic. There is also an online website where visitors can explore basic information about the Jomon culture and the sites in Japanese and English. Moreover, the website provides information on how to access the suggested destinations, both by public and by private transportation. Aomori’s good practice to provide such nondigital and digital infrastructure reminds us about the significance of tourism infrastructure in regional tourism, even in an area that is not yet popular with foreign tourists.

Nonetheless, we are also interested in discussing the tendency of Aomori to attract female tourists more. From the lyrics of the Jomon promotional video to the marketing of three Jomon Aomori romantic courses, including the popular food selections among Japanese women such as sweets- and vegetables-loaded food, Aomori’s tendency to attract young women to consume the offered culture is indicated. The research result implies that the term romantic used in Aomori Jomon Romantic Journey is not similar to that used in tourism that offers the opportunity for tourists to engage in romantic affairs with travelling partners [

72,

73] or locals [

74]. The romantic itinerary suggested by Aomori is closer to the historical nostalgia that allows visitors to escape the present by imagining themselves living in the Jomon period and the later civilizations that flourished in the prefecture. From the design of the romantic itineraries and Jomon Time-Slip song, we presume Aomori has the intention to target rekijo, the history fangirls who enjoy visiting historical sites featured in Japanese pop culture. These fan girls have not only driven pop-culture-induced heritage tourism, but they have also mobilized a participatory movement to safeguard that cultural heritage [

4]. For a long time, Japan has acknowledged the power of dedicated pop culture fans for the urban economy. Henceforth, the Japanese adoption of a strategy that can turn fans into engaged superfans is no longer surprising. Even so, the case from Aomori shows the first attempt in Japan to draw dedicated fans to fall in love with the region’s prehistoric assets.

Apart from the discussion about the incorporation of fantasy in heritage tourism, the result of this study also implies the contribution of the Jomon Rally Stamp to drive tourists to visit many archaeological sites within a limited period. This activity can be considered a promising approach since a previous study discussed in the literature review [

41] mentioned the difficulty of attracting people to enjoy archaeotourism if they are not really into archaeology. This rally stamp activity gives tourists a reason to visit and explore the sites even for a short time. Tourists might be interested in seeing all areas introduced in the campaign since they have the opportunity to win the rewards if they complete the challenges. The outbreak of COVID-19 indeed affected the tourism activities in Aomori. Nobody expected the widespread coronavirus in Japan would be this serious and lengthy. Nonetheless, this study documented Aomori’s innovation to respond to the pandemic by introducing an online rally stamp to replace the traditional version. Thus, yet again, this study verified the contribution of digitalization to heritage tourism. Henceforth, we would like to argue the importance of speeding up such digital transformation, which is beneficial during the widespread pandemic. Unfortunately, due to data limitations, we could not measure the impact of Jomon time-slip-themed tourism on Aomori’s economy, regional revitalization, and its depopulation issue. As this thematic tourism was launched during COVID-19, the available data are minimal, and it is challenging to conduct additional primary data collection. Henceforth, a future study is suggested when the situation is more conducive for conducting the follow-up research.

7. Conclusions

This study confirmed the practice of Aomori to incorporate fantasy in heritage tourism. It documented an example of heritage tourism that sells time-travel fantasy as its theme. The paper contributes to the literature by highlighting strategies in developing regional heritage tourism by combining fantasy and pop culture to promote pre-historical assets. The case from Aomori describes the possibility for regional cities to induce historical nostalgia, particularly for young people, through the creation of thematic itineraries, production of local historical fantasy pop culture content, and collaboration with local celebrities. These simultaneous strategies might draw younger people to consume cultural content and develop a sense of attachment to the promoted area. Firstly, it allows young people to learn about Jomon culture in the style that suits them the most. If they are more interested in romantic style, they can choose one of the itineraries recommended by the Aomori Jomon Romantic Journey. Likewise, if they prefer to have more comprehensive travel, they might select the itineraries recommended by Jomon Japan. Second, the combination of fantasy and pop culture allows young people to learn about Jomon culture in a more relaxed and fun way. The portrayal of the time-traveler girls in the Jomon promotional video might stimulate historical nostalgia for the generation who have never experienced living in a certain historical period. With the positive response toward the time-slip tourism concept introduced by Ringo Musume on the Jomon Aomori official Youtube channel, there is a high chance that this kind of cultural content might spark younger people’s interest in visiting Aomori directly after the pandemic ends.

Additionally, the case from Aomori also provides us with important lessons learned. The first is related to the importance of tourism infrastructure, creative marketing, and innovation for regional heritage tourism, particularly for those areas with archaeological sites or those categorized as suffering from “undertourism”. The results emphasize the necessity for regional areas to be innovative and resourceful, especially when facing unexpected challenges such as the global pandemic. The second is related to the importance of speeding up digital transformation for the future of heritage tourism. The study revealed how digitization could help regional heritage tourism to keep delivering the cultural content despite the continuous widespread pandemic. Likewise, the Aomori case invites us to consider intercultural appropriation by foreign fans that might appear when the pandemic ends. As the Japanese Government has been using its pop culture to attract foreign tourists, it might be necessary to consider this issue in the future. Lastly, the study suggests further research on Aomori’s postpandemic heritage tourism to determine Jomon time-slip-themed tourism’s effectiveness in addressing the depopulation and declining regional vitality in the prefecture. If time-slip tourism can contribute to Aomori’s regional revitalization efforts, Japan might consider developing more heritage tourism strategies that incorporates fantasy and pop culture.