1. Introduction

For the last 50 years, post-war modernism has been largely debated, criticised and victimised by public opinion in most parts of the world. The UK, however, is one of the countries where this criticism has been most acute, given its strong anti-modernism backlash in the 1970s and 1980s linked to a broader rejection of post-war social welfare [

1]. The arguments usually put forward by its critics are that despite its social and design merits in the post-war reconstruction and ultimately in solving the housing shortage and urban decay, it failed to deliver what it promised and to recognise the damaging consequences of its belief in new technology, technocratic planning and the founding design principles of the modern movement—large-scale, non-contextual, rational order, emphasis on movement and material hardness—on the social life of those spaces designed [

2,

3]. Despite these critiques, the last three decades have been marked by a slow but increasing recognition of the value, significance and legacies of our post-war modernist heritage, particularly of its most iconic buildings [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This was largely influenced by a growing international movement for the conservation of modern architecture and urbanism driven by the formation of international conservation bodies and organisations in the early 1990s such as the International Committee for Documentation and Conservation of Buildings, Sites and Neighbourhoods of the Modern Movement (DOCOMOMO), International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and Association for Preservation Technology (APT) (The International Committee for Documentation and Conservation of Buildings, Sites and Neighbourhoods of the Modern Movement (DOCOMOMO) is a non-profit organisation devoted to the conservation of modernist heritage; the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) is a non-governmental international organisation dedicated to the conservation of the world’s monuments and sites; and the Association for Preservation Technology (APT) is a cross-disciplinary organisation dedicated to promoting best technology for conserving historic structures and their settings.), and of their recognition as heritage in 1987 in the UK.

However, despite all these efforts, most of our post-war heritage continues to be trapped in a battleground of conflicts between conservationists and pro-growth local governments and can only survive by chance. The last 30 years have witnessed a ruthless erasure of our best examples, particularly of our ordinary post-war architecture and public spaces and cityscapes, which for their large-scale and unappealing aesthetics have been considered unfriendly and often dysfunctional [

9].

Post-war heritage enthusiasts, including historians and practitioners, have long been calling for more objective and inclusive histories and assessments of post-war heritage [

10,

11] if we want to save our best post-war heritage. It is well known that this anti-modernism movement has been largely driven by public perceptions of failure [

10]. However, very few studies have examined those perceptions of failure or have put them against the actual everyday lived experiences and uses of their community of users. Furthermore, little attention has been given to the post-war cityscapes and their urban design [

9]. In doing so, they have failed to do justice to the urban heritage that is well-used and even loved by some. This is the case of the Southbank centre in London, which has long served as a democratic place for arts and a social space for its community [

10,

12,

13].

This paper aims to respond to these calls. To do so, it employs qualitative material from one case study, the Southbank Centre (SBC) in London, an iconic, unlisted (Listed buildings are nationally protected buildings. In England, they are listed by the National Heritage and registered in the National Heritage List of England (NHLE).) but also contested modernist ensemble with a long history of conservation and regeneration attempts. It engages ethnographically with the users’ experiences and uses of its publicly accessible spaces at different stages of conservation and regeneration, particularly during and after two of its most relevant regeneration projects (1999–2007 and 2015–2018) were implemented. It focuses primarily on the users’ social activities, which are the most conditioned by the spaces where they occur [

14,

15] and are therefore the most revealing of the limits and opportunities of the original design and re-design. These activities can therefore provide us with a useful lens to analyse the socio-spatial qualities that make the SBC a public social setting and in doing so, can problematise ongoing public discourses of failure and critiques surrounding post-war heritage and its conservation and regeneration agendas. To do so, fieldwork was carried out over a nine-month period in the spring and summer of 2013 and revisited in the summer of 2018, combining ethnographic methods of observation and interviews, and urban design analysis.

The paper is structured as follows. First, it reviews contemporary post-war heritage thinking in terms of conservation and regeneration and the increasing role of the users’ experience in shaping its agenda. Secondly, it outlines the methodological approach of the project and provides some contextual background of the SBC’s troubled history of conservation and regeneration.

Thirdly, it describes the ethnographic and urban design study of the social experiences and uses of the SBC’s by focusing on a range of spaces during and after two of the most decisive conservation and regeneration projects took place. In the final part, it concludes with its contributions to ongoing debates and reassessments of post-war heritage legacies and its implications for future conservation and regeneration agendas.

2. An Overview of Post-War Modernist Heritage Thinking

Contemporary post-war modernist heritage thinking has been haunted by discourses of failure in most parts of the world. In the last fifty years, modernist architecture and planning have been strongly victimised and stigmatised for their material and social failures. These perceptions of failure have been reported in several countries in Western and Eastern Europe and the US, but in each country, they have been politicised differently, despite numerous similarities in terms of their built form—they all followed the same urban planning principles of the Athens Charter (The Athens Charter is a document produced in 1933 by Swiss architect Le Corbusier which promulgated modernist urban planning principles based on studies undertaken by the Congres International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM).) [

16,

17]. Their different socio-political contexts have led to a diverse range of discourses of post-war heritage, and this is perhaps an indication of why the body of the literature on this topic has not yet evolved sufficiently to form an international discourse or consensus on the recognition and protection of modernist heritage.

This paper focuses on the UK context. This is the country where these discourses of failure have been most acute, given a strong anti-modernism backlash in the 1970s and 1980s linked to a broader rejection of post-war social welfare [

1] and the perceived aesthetic, technical, cultural and ideological failings of an inaccessible architecture style, often poorly conceived, that failed to deliver the utopia and the future that it promised. These failures have absorbed a lot of interest from architectural historians. This is attested by the growing proliferation of historical monographs dedicated to understanding the nature and causes of these failures, to restate the designer’s aims and social intentions underlying those works or simply to blame public opinion’s prejudices and unfair taste judgments [

10]. However, as the architectural historian Adrian Forty [

10] expressed very well, there is no point in dwelling more about whether this period is a failure or not; what matters is that it is perceived as a failure and that we should be looking to understand the perceptions of those that judge those works rather the material objects themselves. These perceptions of failure should be recognised, because they continue to daunt all our efforts to appreciate the legacies of the architecture of the welfare state, particularly social housing and public buildings, and therefore to counter any attempt at its conservation and rehabilitation.

Underpinning this rising interest in post-war heritage, we must first of all acknowledge the role of international organisations such as DOCOMOMO. However, the national governments in some countries in Western Europe also had an instrumental role in the conservation protection of modernist heritage [

18]. A good case in point is the UK and its introduction of a post-war listing programme in 1987 for buildings 30 years old or younger if considered outstanding and under threat and in creating statutory heritage bodies—such as Historical England, Historical Scotland and Cadw (In the UK, there are three statutory heritage bodies ”regionally” differentiated between England, Scotland and more recently Wales, which have the task of protecting the historical environment of England by preserving and listing historic buildings, ancient monuments and advising central and local government.), who have acquired a leading role in assessing, listing and guiding conservation practice. These events marked a positive change of mindset towards post-war modernism. Since then, we have witnessed an increasing promotion and celebration of modernist aesthetics [

19]. Several campaigns have also been organised to raise public awareness on modernist heritage and legacies [

20,

21]. Post-war modernism has also gained momentum among academics, particularly from design disciplines [

2]. This is attested by numerous international conferences dedicated to uncovering the overlooked elements of modernist history and to advancing new methods of surveying, recording and documenting.

Driving the statutory recognition and growing interest for post-war heritage is the establishment of the new conservation paradigm, which has put forward an expanded understanding of the designation and scope of heritage [

22]. Conservation in the strict sense, understood as preservation of the physical fabric of buildings of historical interest, has gradually given way to an idea of conservation planning and management of change which values both tangible and intangible cultural values. Conservation approaches are becoming more operative, involving increasingly ethical judgments and following codes of good practice guided by the general public as well as professional opinion [

22,

23]. For many scholars and practitioners, this represents a move towards the democratisation of conservation because its practice is no longer only a concern and duty of the experts, usually the conservationist’s elite [

22]. The understanding of significance of historical heritage is also being redefined to encompass the sum of all heritage values attached to a place: evidential, historical, aesthetic and communal [

24,

25]. Alongside all these changes, architectural interest and design value have also started to become equally valued as historical interest and as the physical objects themselves [

26,

27].

However, despite this paradigm shift in conservation which has brought positive change in post-war heritage conservation, there continue to exist huge dilemmas about what post-war heritage is worth listing and how it should be preserved or renovated [

28]. This is a phenomenon worldwide, and it is not surprising, given the ongoing conflicts between the conservation and urban regeneration agendas [

9]. It is well known that urban regeneration has become post-war heritage’s fiercest enemy. Since the 1990s, any move to preserve and rehabilitate post-war heritage’s often unfashionable and dysfunctional landscapes has been seen contrary to the cities’ urban growth and regeneration agendas and interests in modernising their images and attracting investment [

29]. Most post-war heritage facing regeneration has been often totally or partially remodelled or demolished to give place to newer landscapes. This is not to say that there have always been conflicts between the conservation agenda and the urban growth regimes. There are many examples that show that they are not mutually exclusive, especially given the increasing national and local demand for heritage evolving around commodification and consumption [

30,

31].

There are more issues at stake, though. In the UK, many of these conflicts are partly explained by an ongoing ideological divide between heritage bodies, conservationists, historians, designers and academics. Not only do they interpret modernism differently but also approach its conservation and regeneration in distinct ways [

32].

Heritage statutory bodies, both international such as United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) and ICOMOS, and national such as Historical England, have played a fundamental role in mainstreaming post-war heritage conservation through the creation of assessments and guidance in the form of charters, principles and codes of practice [

33,

34]. Many of these are quite comprehensive assessments, including thematic research (i.e., building types), consultation with owners, local authorities and the general public and evaluation of a range of values (e.g., communal). However, they are broad in scope, as they can be applied to any type of historical heritage and serve a wide range of outcomes (e.g., from identification to implementation). A lot of progress has also been made in documenting the various types and best precedents of post-war heritage; however, there is still little conservation and regeneration guidance for this specific type of heritage [

34]. Most practice to date continues to be predominantly archi-centric—focusing mainly on the iconic architecture and its physical and visual qualities—and often tends to focus more on conservation than regeneration, though there are some recent examples that have managed to successfully integrate the two [

9,

31].

Conservation professional bodies such as the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC) (In the UK, there are three statutory heritage bodies ”regionally” differentiated between England, Scotland and more recently Wales, which have the task of protecting the historical environment of England by preserving and listing historic buildings, ancient monuments and advising central and local government.) have been primarily focused on the production of quality standards [

24]. However, despite their effort, they tend to place conservation above regeneration practices, emphasising repair rather than re-use, dismissing the new conservation paradigm’s emphasis on managing change—not to mention that their advice is quite prescriptive and technical and cannot always be applied to modernist heritage, which often constitutes a break with traditional architectural forms, methods of construction and materials [

11].

Architectural historians and designers are less familiar with conservation practice but have a deeper understanding of modernist history and theory. Their longstanding focus has been on understanding the causes that make modernism a failure, and as such, they have focused on the architecture and its qualities and the intentions of its producers [

26]. However, by doing, so they have failed to move beyond histories of the material objects, and as such to understand the actual public perceptions, despite the recognition that the architecture’s failures are often a matter of perception. It is a fact that most written histories have shown little engagement with the private and social experience of its community of users [

10]. Nonetheless, architectural historians as well as designers have been instrumental in bringing more creative thinking into conservation practice and for modernist seminal texts to guide modern architectural conservation [

10]. However, by placing too much effort on preserving design authenticity, they tend to sacrifice contemporary needs and economic viability and pose challenges to mainstreaming its conservation [

32].

The more radical views come from philosophers, writers and academics [

19,

35], who have established a form of architectural investigation founded on social and critical theory. According to some, modernism had no interest in its conservation. It was always hostile to the idea of continuity and of becoming heritage or being classified into the art-historical styles.

Cutting across these divides, there are a number of common trends. The first is that a stronger emphasis on heritage conservation prevails over regeneration, by the provision of general rather than specialised standards and guidance which focus on the identification and preservation of its original qualities rather than its adaptation and reuse for new needs [

11,

36]. The second is the archi-centric focus of histories and assessments of post-war heritage, and stronger enthusiasm for the iconic rather than the ordinary architecture and the urban design of modernist public spaces and cityscapes. The third is the little or no engagement with the community of users that inhabit those spaces to understand their experiences and uses, despite the growing recognition that conservation is more an issue of performance of use, comfort and perception than a simple restoration of historic qualities [

9,

37]. The last two issues are central to the analysis of this paper and therefore require further scrutiny.

4. Methodology

As discussed in the previous section, the experiential value of our heritage is becoming increasingly recognised in current histories and assessments. However, there are still factors impeding its inclusion in the conservation and regeneration agendas. The major one is methodological. Research experience requires qualitative research methods, but these are not mainstream within practices of heritage conservation and regeneration [

43], which are more in favour of “speed, efficiency and compliance” [

44] (p.26). This is not to say that there is no work focused on experiential value because there is, but much of it has been using more quantitative methods such as surveys that failed to provide in-depth accounts of people’s “values, perceptions and behaviours” [

45] (pp. 46–47). Furthermore, there are methodological challenges. Recent research demonstrated that in order to capture the everyday experiences and practices of heritage settings, we ought to use more sophisticated qualitative methods, such as new types of mobile ethnographic methods (e.g., go-along or walking interviews), which constitute a hybrid between observation and interviewing methods [

38]. These methods are considered effective, allowing close observation and engagement with the participant’s embodied experiences and actions and their immediate translation into verbal descriptions [

46,

47]. However, these methods are not always productive enough to objectively study the material, spatial and design qualities of spaces where such experiences occur, as they are highly dependent on the input of interviewees.

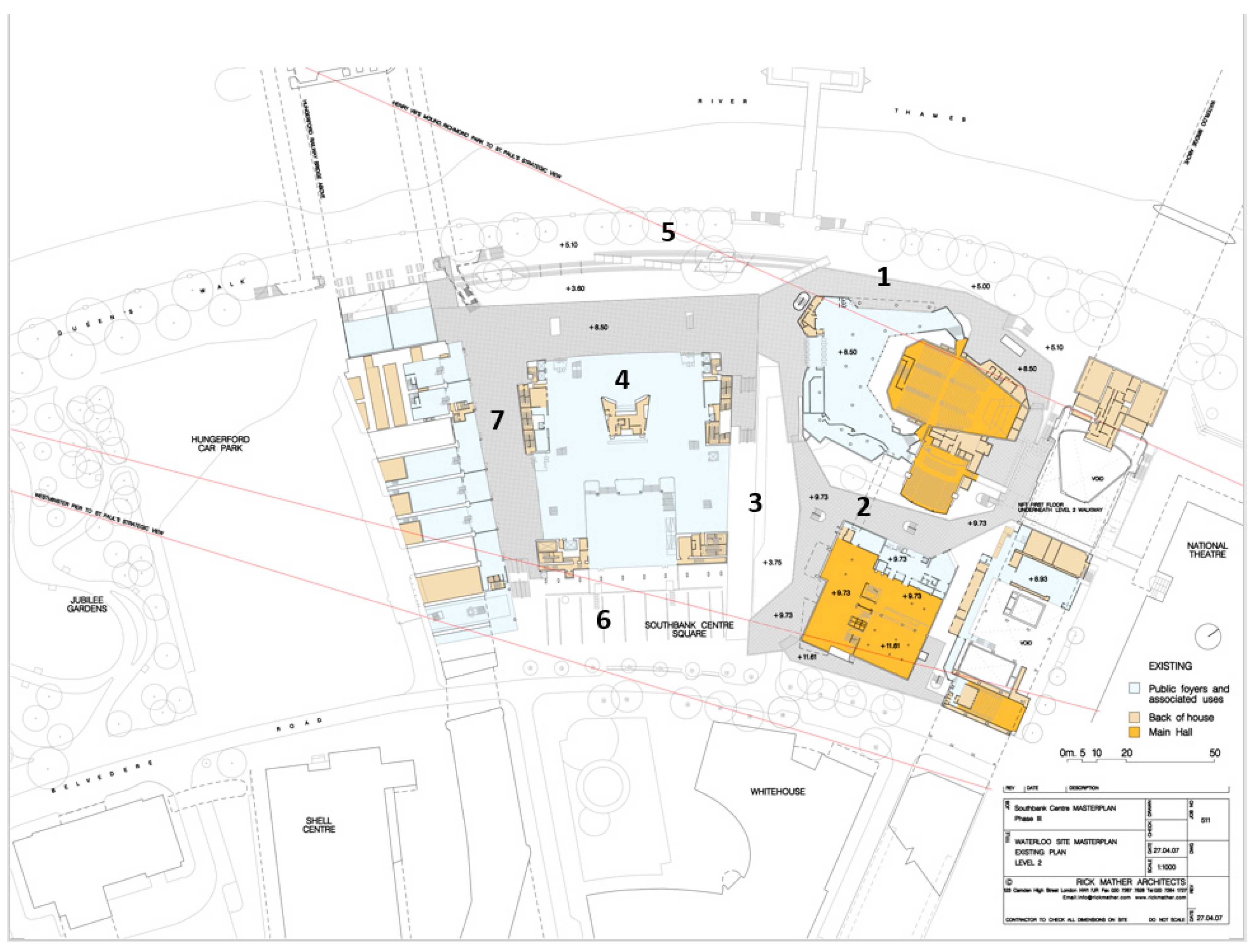

The research in this paper is informed by these new approaches, their strengths as well as their limitations. To do so, it places the users’ experiences and the urban design at the centre of the analysis, by using a combination of mobile ethnographic methods including walking interviews, observations and urban design analysis. Fieldwork was undertaken during a nine-month period in the spring and summer of 2013, a very contested period between the two major projects of regeneration and revisited in the summer of 2018. It researched a range of public spaces in different stages of development—during and after the two masterplan regeneration projects had taken place—to examine how they are experienced and used and by whom, and what role those spaces and their urban design have played, including original design as well as new design interventions, in supporting or constraining such uses. The researched spaces included “original designed spaces”, still awaiting intervention in 2013; “retrofitted spaces” that were subject to conservation and regeneration interventions in 1999–2007 and/or 2015–2019; and “new spaces” subject to interventions in 1999–2007 (see

Figure 1). Observations and interviews were conducted primarily when the weather conditions were favourable for outdoor activities. The observations focused on the range rather than the number of uses taking place in public spaces, with a particular focus on the social activities, also considered resultant activities from necessary as well as optional activities, which are the most conditioned by the spaces where they occur (See

Supplementary File S1) [

14,

15]. For the walking interviews, a total of 24 participants were recruited with the help of the SBC’s and South Bank Employers Group and their social media channels (See

Supplementary File S2). During the recruitment process, we invited only participants with a high level of interest, attachment and/or knowledge about the place, to ensure good engagement during the interviews [

48]. We also interviewed a few SBC stakeholders (executive team and designers) in order to obtain the necessary background information for this study. Urban design analysis was also undertaken to examine the uses against the design aims, processes and outcomes [

14]. Before presenting the findings, an introduction of the case study and its context is necessary.

4.1. The Southbank Centre

The SBC is not only one of the largest and most iconic post-war modernist cultural centres in Europe, but also one of the most controversial cases of post-war conservation ever [

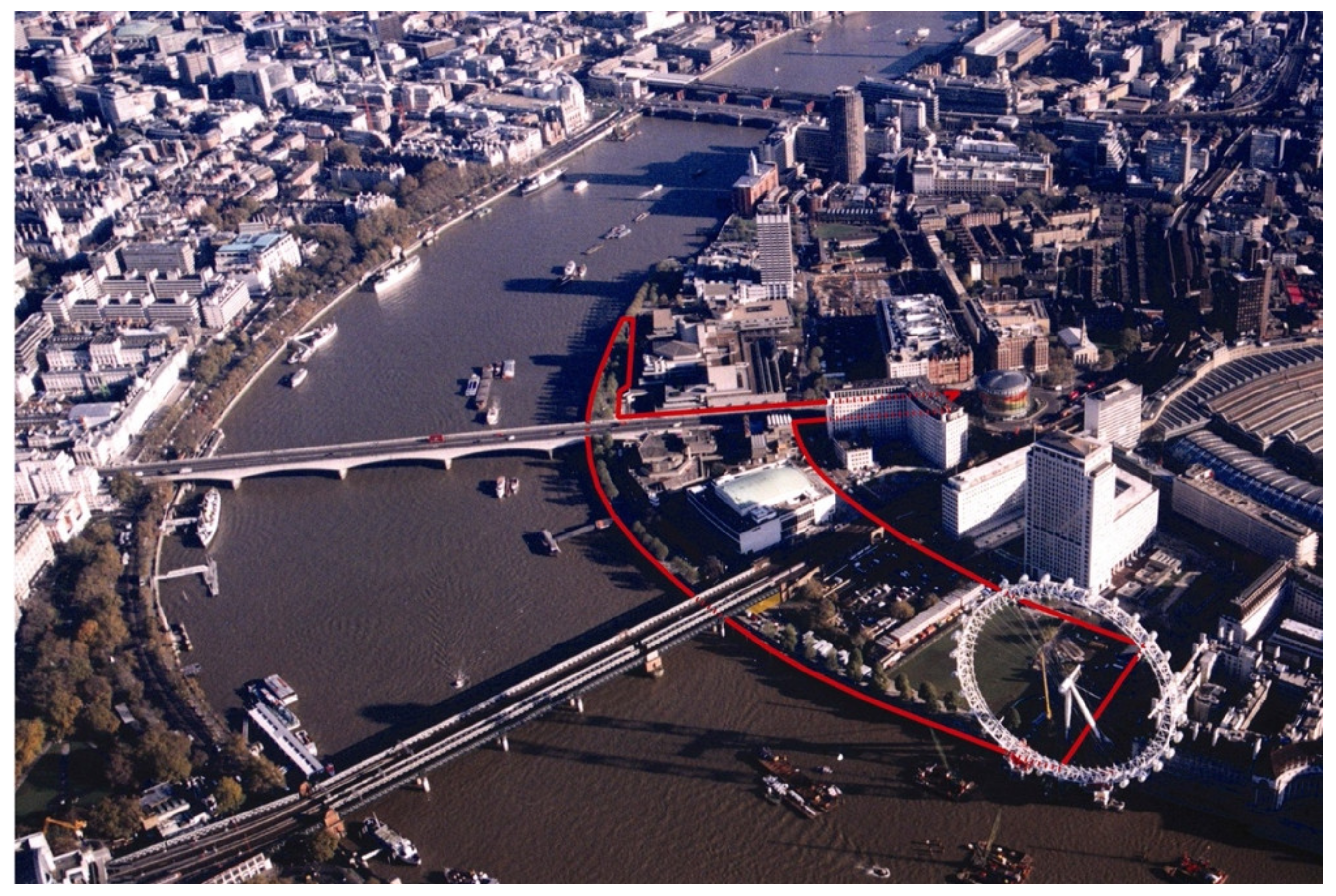

45]. It is a large-scale 30-acre estate, located in the south of London next to the River Thames (

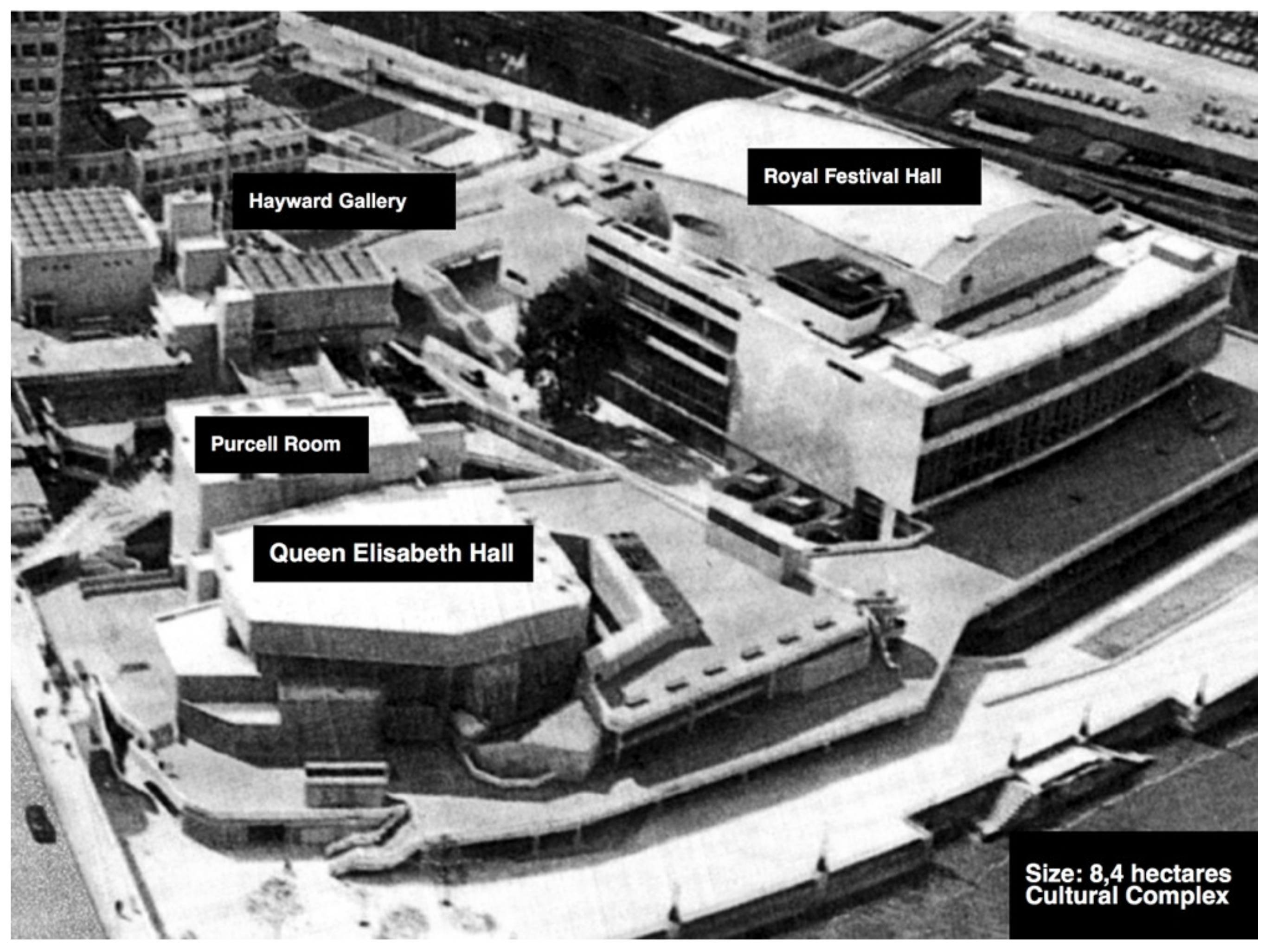

Figure 2). It consists of an ensemble of four iconic modernist buildings and the public spaces around them. One is its central piece, the very much praised early modernist Royal Festival Hall (RFH) and only listed building inherited from the Festival of Britain of 1951; the other three are the contested 1960s modernist and Brutalist buildings and were added later, namely, the Queen Elizabeth Hall (QEH), the Purcell Room (PR) and the Hayward Gallery (HG) (

Figure 3). There are not many buildings like the SBC with such a long history of controversies about their value and which have suffered so many threats of demolition. Interestingly enough, these controversies were already in the making before the 1960s buildings were even built. There was a lot of resistance from the community to the construction of these new buildings because of their large-scale and unappealing design [

49,

50]. Hence, it was not surprising that, in less than a decade after implementation, most of the SBC’s public spaces were already suffering some neglect and underuse, even though some refute that analysis [

13,

51]. However, before analysing these debates, we need to learn more about the SBC’s original design and the designer’s aims as well as its critiques and counter-critiques.

4.1.1. The Original Design, Its Critiques and Counter-Critiques

The SBC is considered a snapshot of the avant-garde architecture of that time [

51]. It was designed by the London County Council (LCC) Architects Department in one of its most glorious and experimental moments.

Three of its architects were also part of the infamous Archigram group that epitomised a new type of modernist architecture born of inspiration and rebellion, which sought to re-evaluate architectural practice and to redefine the nature of architecture itself. These ideas were quite radical at the time, and even discomforting to the mainstream of modernism and the group of brutalist’s enthusiasts. Indeed, Archigram were known for their radical and seriously fun ideas of an “architecture of endless becoming”, in other words, an architecture that provides “the equipment for living, for being” [

51] (p. 5). The most exemplar in this respect is the SBC.

The SBC has been praised for its original design and manyfold architectural innovations, though this was not without its controversies. It was designed with a popular concept at the time, the concept of “building as a city” or “the city as a single building” [

50] (p. 11). Underlying it were a couple of important design considerations, which reflected the design trends and interests of the time. These included:

Although the SBC would be praised by some modernist enthusiasts for its technical and spatial qualities, particularly of its auditoria and foyers, architectural critics and historians and the general public were divided about the SBC’s legacies. For some, the SBC was a novel contribution to the “art of the organic town planning” and one of the best exemplars of brutalist architecture [

50] (p. 23). For others, it was and still is unappealing because of its scale and radical, unfinished and incoherent aesthetics [

40,

53,

54], and it is “impractical” for everyday use—particularly its system of walkways which were never implemented in its entirety—and “challenging to adapt without destroying the architectural integrity of the ensemble” [

50] (p. 23). However, the actual users’ lived experiences of these spaces were never taken into account, so if we want to do justice to the SBC and its legacies, we ought to include them in these debates.

4.1.2. An Overview of Regeneration Attempts Since the 1980s

After only ten years of existence, the SBC was already considered unfit for its uses because of deficiencies of the original brief but also of changes of expectations and uses [

50,

55]. This context led to a series of initiatives to renovate its buildings and public spaces. The most well-known are the proposals by three established British architects, Price in 1983, Farrell in 1985 and Rogers in 1993, to redesign the SBC’s buildings and public spaces [

56]. However, they were short-lived. They were all very expensive ventures and clearly unsympathetic to the 1960s buildings but were very representative of the first conservation trends of the 1980s with a post-modern style that only focused on changing the architectural expression of the development [

57].

After a long history of failed regeneration attempts, the SBC’s executive team decided it had had enough of architects’ ego trips [SBC Stakeholder 1]. Having spent over 5 million pounds in plans and yet achieved no improvement, the executive team launched in 1999 an open international competition to search for a master planner with a totally different approach: to get the arts and urban design needs resolved before the architecture; to undertake an incremental rather than a “big bang” implementation. This was the first time that SBC’s executive team had a strong vision for the site.

The international competition received a total of 76 entries. The winning entry was from Rick Mather Architects (RMA) (RMA, Rick Mather Architects, is an architectural, masterplanning and urban design practice based in London. It was founded in 1973 by Rick Mather, an American architect, and since his death in 2013 has been led by two partners, Gavin Miller and Stuart Cade, who have since launched a new practice, MICA.), an architectural practice based in London, well known for its sensitive approach to architectural heritage and context [SBC Stakeholder 2].

The SBC’s executive team undertook a public consultation on the draft brief [SBC Stakeholder 1]. The consultation revealed a high level of consensus on the key issues that needed to be addressed—poor accessibility to the site, poor quality of the visitors’ experience—but little agreement regarding the future of the 1960s buildings and the expected focus on retail development [

58]. Following this, RMA also did substantive urban and architectural research which was presented in two design reports: an urban design strategy [

49] and a volumetric study [

59]. Underlying these reports were two key ideas: to preserve the old as well as to build new buildings and an awareness that complying with the arts brief called for considerable additions and alterations to the 1960s buildings and achieving consensus among all the interested bodies, thus requiring from RMA a well-informed but neutral response to the site. These two ideas were put forward in the final masterplan brief [

49,

60]. This was structured into two phases: the first, between 1999 and 2007, prioritised the public realm improvements, and the second, between 2007 and 2019, addressed the conservation and regeneration of the 1960s buildings (

Table 1). Due to increasing economic constraints and local resistance, the first phase was prioritised over the second because it faced less opposition.The first masterplan phase brought many improvements to the SBC’s public spaces, making them more attractive and busier [

61]. However, it also put the 1960s buildings under great pressure, as they could no longer meet the rising cultural demand. This context led the SBC’s executive team to rethink its regeneration strategy [SBC Stakeholder 1] and to commission Duffy Eley Giffone Worthington, an architectural consultancy also known as DEGW (DEGW was the former architectural consultant during the competition brief. It was established in London in 1971 and was specialised in the design of office environments and was one of the first practices to place an emphasis on how organisations use space and the important role that design has to play in this.), a feasibility study on the current artistic and audience standards, and a new masterplan brief which emphasised testing ideas through more ephemeral temporary and economical installations before making any physical shift, revisiting the spirit of the 1960s buildings and the Festival of Britain [

62]. This strategy was first tested with the Festival of Britain celebrations in 2011 and subsequently replicated every year.

4.1.3. Amidst Listing Refusals, Heritage Challenges and Public Resistance

During its first masterplan phase, the SBC saw its listing refusal five times, in 2004, 2007, 2010, 2012 and 2018, despite rigorous recommendation by Historical England (HE) and the Twentieth-Century Society [

37,

49,

50,

63,

64]. In 1991, Professor Andrew Saint had already suggested in a report for HE that the SBC’s case would be highly contentious [

50]. Nevertheless, Saint did his best to put together rigorous recommendations for preserving the SBC.

In 2012, the SBC executive team decided to apply for a certificate of immunity towards the refurbishment of the 1960s buildings, bringing this lengthy history of listing requests and refusals to an end [

65]. However, for many architects and historians, this did not represent a defeat. Listing is no longer a guarantee than can save these buildings [

66]. However, after the completion of the first masterplan phase, a series of other heritage challenges and public resistance followed. The Twentieth-Century Society, the SBC’s main watchdog, expressed strong reservations regarding the second masterplan phase, particularly its proposals to partially remove the walkways [

67]. Unexpectedly, HE was less strict about allowing change as long as all the buildings were retained. However, heritage resistance would only turn into conflict when the winning entry of Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios (FCBS) architects to refurbish the 1960s Festival Wing’s buildings went for public consultation in 2013. Their proposals to create a 12 m high glass pavilion arts and retail uses and permanently move the skaters from the undercroft to a nearby location proved very controversial [SBC Stakeholder 3] [

68]. Although the SBC was able to secure broad support from the Mayor of London, Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) (CABE was the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment in England. It was founded in 1999 and merged in 2011 with the Design Council.) and even the former LCC architects, and public consultation (85% approval), a strong local and international public resistance to development of the 1960s buildings emerged [

69,

70,

71], initiating the campaign “Long Live Southbank” (LLSB) to save the skatepark. This LLSB Campaign led to over 27,000 objections to the SBC’s planning application, forcing the SBC team to sign a binding agreement that the planned refurbishment of the 1960s buildings should only go ahead if it kept the undercroft space for skateboarding [

65,

72].

In 2015, a new LLSB campaign followed to keep and restore the original design of the undercroft spaces [

73]. By then, their relationship with the SBC had improved, leading in 2017 to a joint planning application and fundraising campaign to pay for the undercroft’s refurbishment [

74,

75,

76,

77].

In the interim, the SBC also managed to secure £25m from the Heritage fund the Arts Council England and the refurbishment of the 1960s buildings could finally go ahead in 2015 [

78,

79]. The SBC team was by then in full agreement that a sensitive refurbishment of the original design qualities of its interiors and exteriors was the most sensible solution [

28,

63,

80].

The refurbishment of the 1960s buildings was completed in 2018 and the skaters’ undercroft shortly after in 2019. Their re-opening was celebrated in 2018 with an exhibition titled “Concrete Dreams” which paid tribute to its buildings and initiated a major heritage programme to open the SBC’s archive to the public [

81]. However, even now that the refurbishment has been completed, there are still concerns that the SBC’s Certificate of Immunity will not stop further developments. It is with this context in mind that we felt it was pressing to examine the users’ experience of the SBC before, during and after the renovations took place.

5. The Experiences and Uses of the Original, Retrofitted and New Designed Spaces

As a comprehensive review of the findings is not possible here, this section only examines three of the seven researched spaces that offer the most productive illustrations of the social experiences and uses of the 1960s buildings during and after the two major masterplan interventions had taken place. These include the high-level walkways, which are the best exemplars of the original design but also most contested spaces facing public resistance to development and therefore most still in the original state until 2015; the Queen Walk riverfront spaces, retrofitted in 2007 that have faced major alterations in its layout and use and have brought a lot of divided public opinions about its new uses; and the Southbank square, a newly created space in 2007, after the implementation of the first regeneration phase.

5.1. Festival Wing High-Level Walkway Spaces

The walkways of the 1960s buildings have a long history of conflicts. Since the 1980s, there have been several attempts to demolish them. This explains why, in the first masterplan phase, various ways were explored to enclose the undercrofts and terraces and remove segments of walkways in order to increase the amount of useful space. These explorations resulted in several proposals in the first masterplan phase to fill many of the undercrofts and walkways with active facades (mainly cafes and restaurants). In the second masterplan phase, the proposals would change direction with the idea to combine active facades with other flexible and economical strategies, increase permeability across the whole site through the creation of new openings and staircases and use more temporary design strategies to animate the site through temporary uses and public art.

During fieldwork, we focused our attention on three particular walkway locations: the walkway segment between the QEH, PR and HG both below and above street level, namely ground floor and levels 1 (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) and 2, the roof terrace (

Figure 6). The three locations were at the centre of attention of the media since the winning Festival Wing proposal of FCBS architects was shown in 2013 at a public consultation. Their proposal was surrounded by a very heated debate because of their intentions to insert in this space two big glass pavilions—a vertical one in between for rehearsing orchestras and a new central foyer, and a horizontal one along the waterloo bridge. The main opponents to this proposal have been conservationists such as the Twentieth-Century Society, architectural critics, the director of the National Theatre, and the SBC’s regular users [SBC Anonymous Users Interviewees].

Our fieldwork observations were quite revealing. The first two walkway locations, ground floor and level 1, were the locations where we observed the greatest number and variety of social, optional and unplanned activities (of all kinds from people-watching, socialising to parkour). Our interviewees also confirmed that the walkways are the “most popular spaces” at the SBC. However, the situation changed as soon as the “Festival of the Neighbourhood” (2013) began in June. As observed, the occurrence of Festival events displaced many of the optional activities (namely, the performative ones, such as street dancing) and reduced their occurrence. These activities have become less regular during weekdays than weekends, only occurring when there are no events.

The third location of the roof terrace is a recently gained public space with an interesting history. It was for a long time closed to public access until the SBC decided to re-open it for the first Festival celebration in 2011 to use it as a roof garden. After that event, it was closed again for a year, but given its great success, the SBC decided to finally re-open it again in 2012 to make this a permanent public space combined with a few green spaces. According to the SBC creative director [SBC Stakeholder 4], this idea took inspiration from the original design of Archigram. Since the roof terrace opened permanently, it was an instant success. It became one of the top destinations in the SBC, especially during good weather. It is a prime destination for social activities related to drinking and picnicking. These findings came out as a surprise, since these locations were, since the 1980s, considered doomed to failure and subject to several proposals of demolition. The SBC executive team was so concerned at the beginning that people would not find it, deciding therefore to paint the concrete stairs in yellow and put a sign inviting people to come up. The next masterplan intervention consolidated the function of this space as a public open space, making it more accessible and enabling its use as the principal secured riverside installation space.

Fieldwork observations and interviews revealed that the walkways on the ground floor and at levels 1 and 2, have a number of supportive spatial qualities that make them truly “open regions”, i.e., good informal social settings [

82]. At the street level are located all the service areas which are characterised by reduced visibility and therefore offer favourable conditions for most optional and unplanned activities to occur. At level 1, the walkways provide circulation spaces with great spatial variation in terms of layout and views [

83]; a lot of edge spaces along the circulation spaces where people can sit and lean against and children can play; a variety of public art with a double function of seating spaces and props; and, most important of all, a lot of space that allows many activities to take place at the same time without obstructing each other. At level 2, the roof terrace offers circulation spaces as well, with a variety of views to the river and to the other spaces; and a variety of seating spaces from movable chairs and tables, which according to Whyte’s theory [

15] are the type of seating space that allows more social flexibility, to long fixed benches at the edges of the circulation spaces (good for groups and individuals) and artificial grass (which seemed the most popular seating space). From all these supporting conditions, the grass was seen as the most important element to promote social use. As a matter of fact, it was the space that worked best as a social prop. All types of users, from groups to individuals, came here to socialise, get some sun or simply to rest.

Altogether, these findings reveal that, despite all the ongoing proposals to improve these spaces, not much effort was required to activate them. It does not really seem necessary to make permanent interventions. Temporary uses and public art interventions such as a bit of grass, some planting and props are just enough to make these spaces more attractive and inviting.

5.2. Queen’s Walk Riverfront Spaces

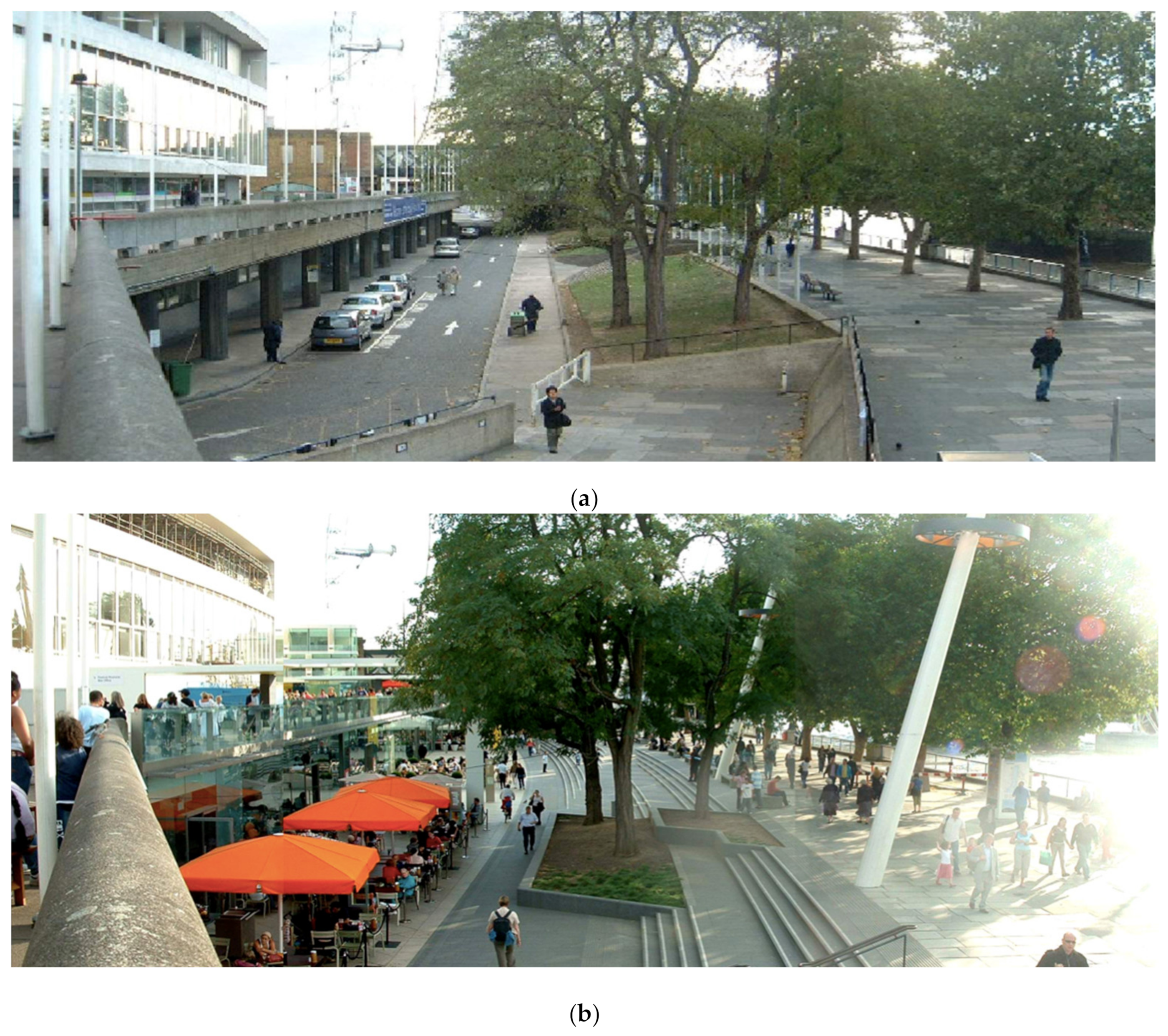

The Queen’s Walk was, for many decades, a desolate place. Even if it was a prime location with excellent accessibility and visibility, and within relatively close distance to other top destinations such as the Tate and the London Eye, the SBC’s riverfront was never a primary destination for many people (

Figure 7a). This perception only changed when some major interventions took place at the Queen’s Walk. In 1999, the service areas were removed from the public realm, and in 2003, the landscape architects Gross.max created a new square with external seating in front of the RFH and active facades with shops, cafes and restaurants (

Figure 7b). Since 2007, public opinion has become more positive. The walking interviews attested that residents, workers and visitors to the area are of the opinion that these interventions have brought new life to the riverfront [SBC Anonymous Users Interviewees], though there have been harsh critiques from the press, particularly from architectural critics, that it has become too consumption-oriented [

69,

70]. Our field observations were necessary to clarify these perceptions namely, how the riverfront spaces were being used after the intervention.

The urban design intervention has definitely increased the public space surface, providing additional seating spaces and more activities and attracting more stationary activities. Although the riverfront spaces continue to be quite empty during the mornings (until 12:00 p.m.) and primarily used as walking spaces, a substantial increase in social activities was noted. This is a positive outcome even though most of the time these activities occur indoors, in the cafes and restaurants or esplanades, and they are more of the type of eating and drinking, and therefore conditional to consumption. It is a fact that these activities are the most promoted by the SBC; after all, it is full of places to eat and drink. However, many users were disappointed with this overload of retail uses, as they are in conflict with the democratic arts place that the SBC claims to be [SBC Anonymous Users Interviewees].

Few optional activities were observed in May, the first month of observation. Only when the “Festival of the Neighbourhood” began in June and all the pop-up installations were installed did they start to occur. The installation of street vendors (the Mexican food truck and the ice-cream vendor), pop-up garden exhibition, the pop-up beach and occasionally a food market immediately changed the feel and use of the riverfront. These temporary uses made people slow down their pace, stop and even stay. Around these uses, we observed a greater incidence of play activities around the pop-up beach, brief social encounters among strangers around the pop-up gardens and some unplanned situations, though unfrequently, such as political demonstrations and looser behaviours, such as people sunbathing. During summer, we also observed that the amalgam of all these uses made theses spaces extremely popular and even sometimes highly congested. On some occasions, it was visible that the situation was becoming uncomfortable and unbearable for some users. Most interviewed people even said that during summer, they tend to “avoid these spaces”, though they acknowledged that Londoners are used to being in busy places and “the more people they have, the more reasons to be there” [SBC Anonymous Users Interviewees].

Altogether, these findings show that the implemented urban design strategies were both successful and unsuccessful in addressing the lack of social uses at the riverfront. This is particularly the case for the decision to include active frontages with only retail uses, which visibly brought more people to walk in this area of the riverfront but did not support several optional and unplanned activities. The SBC executive team seemed to have been conscious of that when deciding to include temporary uses which could compensate the lack of diversity of uses. However, the observations also reveal that the use of temporary uses also carried both positive and negative outcomes. Although they positively activated the riverfront spaces, their overuse has also created congestion and discomfort for many users.

5.3. Southbank Square

The Southbank Square was for many decades used as a car park and docking area. In addition to that, it was also partly covered and overshadowed by a high-level walkway that connected the Festival Wing with Waterloo Station (

Figure 8a). After the first masterplan intervention, it was subject to dramatic changes (

Figure 8b). A segment of the walkway was removed in order to create a new square following the sixth urban design principle (

Table 1). This was one of the first projects to be implemented in 1999. Then in 2003, a new active frontage was added to this facade of the Royal Festival Hall with the opening of the Festival Café. Finally, in 2007, refurbishment was completed, with new pavement and lightning features. These interventions have indeed turned this space into an attractive square. However, even after the improvements, we observed that it is not yet used to its full potential. It is not really used as a square, as it was initially intended by the architects. Our walking interviews confirmed it mainly functions as a “circulation space” [SBC Anonymous Users Interviewees]. There is “not really any reason to spend time there”. We also did not register any significant social or optional activity until the SBC started to organise temporary uses and events to enliven it. Like the riverfront, social activities only took place in the indoor spaces of two restaurants in the square. As we came to understand, this was partly explained by some of the limitations of the urban design, such as the lack of seating spaces and diversity of uses. This situation of underuse only changed, or better put, improved when the food market came regularly during spring every weekend from Friday to Sunday and when the “Festival of the Neighbourhood” started in the summer. The effects were immediately visible. The square transformed itself for three days into a “marketplace with an informal feel” as it only caters street food [SBC Anonymous Users Interviewees]. The square suddenly became busier. It was thriving, with people shopping, eating and drinking and socialising.

The market provided additional seating space, such as two areas of tables, but people still had to fight for space: sitting at the steps of the white house, a residential block, across the street, against the walls alongside the walkways or at the temporary stair that links the square to the first level of walkways. The seating situation improved when the “Festival of the Neighbourhood” brought two art installations, a Bell tower and public art green sculpture. These two art installations provided more seating space, changing the use of the square both at the weekends and on weekdays. This is particularly true of the Bell Tower, which became a highly popular hangout spot. People started to gather around it all the time, even when the market was not there. These observations confirm Whyte’s theory [

44] that people will not stay in a place if there are no enticing elements: such as seating spaces or food.

What was striking, however, was that unplanned activities did not increase substantially even after the market had been installed. Although we observed a few chance encounters among strangers around the Bell Tower, which worked well as a social art piece and thus a social node, we only observed optional activities twice and always on weekdays—e.g., people dancing tango. A more in-depth analysis revealed that the market occupied the whole square almost entirely and therefore did not allow enough space for such activities to happen.

In sum, from the observations, we were able to conclude that although the square was subject to great improvements, both permanent and temporary, these were not sufficient to address the limitations of this space. First of all, the permanent design strategies did not provide enough amenities such as seating spaces and active frontages with activities other than cafes that could attract a larger diversity of people to use the space. Second, although temporary uses such as the occasional food markets and art installations have temporarily compensated for the problems of the site, we again identified both advantages and disadvantages to using them. Temporary uses such as the market were helpful in supporting some uses, particularly those related to eating and drinking, but were also seen to constrain and displace others, especially the ones that demanded more space, such as artistic activities.

6. Discussion

The analysis provided a range of new insights on the actual lived social experiences and uses of three of the SBC’s public spaces in different stages of conservation and regeneration.

Fieldwork showed that all the three spaces have proved to be well-used even if requiring sometimes temporary uses to enhance their activity levels. They also attract a wide range of user groups. These findings problematise that the 1960s spaces are not so “unappealing” or “impractical to use” [

50]. The analysis also revealed that the three different spaces are experienced and used in fundamentally different ways, and this attests in great part to the significant role that their spatial and urban design qualities (original, retrofitted and new designs) play in this.

The high-level walkways are the ones that provide more scope for social and optional uses. Their original design seems to provide them with the necessary affordances for such uses. Their openness and undetermined nature in terms of layout and function, and organic design, are important features in this respect. Both spaces were designed as “architectures of endless becoming” [

51], and this is what they seem to have become. It is precisely this idea that makes them sociologically more open, allowing and accommodating a variety of informal uses. This is something that needs to be acknowledged, because it challenges critiques that they are “impractical” for everyday use.

The Queen’s Walk riverfront and Southbank square, as a retrofitted and new public space, respectively, benefited from great improvements after the first regeneration project and both now feel part of the public realm. Both of them are generally better used than they were before, catering to a good range of uses, but they unfortunately are not yet used to their full potential. Although the regeneration design interventions have successfully reclaimed these public spaces, they have not been able to activate them enough. In both spaces, design interventions have been quite prescriptive and regulatory. This is visible in their introduction of a limited diversity of uses, and their focus and reliance on commerce, which seems to undermine other uses. In doing so, the new redesigned spaces offer a great contrast to the original spaces, as they lack the open qualities of the original design. However, despite their limitations, at least the new design interventions show that these spaces can be retrofitted, therefore challenging ongoing critiques that they are “challenging to adapt” [

50].

7. Conclusions

This paper explored the urban design and the everyday users’ social experience and uses of post-war modernist urban heritage during and after two major conservation and regeneration projects. The urban design and the users’ experience are largely under-explored in the literature but increasingly relevant if we want to provide more objective and inclusive post-war heritage assessments.

Taken together, the findings demonstrated the importance of including the users and their social experiences and uses in the analysis and confirmed that they are as much determinant factors as the materiality of the spaces in assessing heritage value. From fieldwork observations and interviews, we gained insights about the spaces that people use, like and value most. The substantial differences between the three spaces, in terms of experiences and uses, show the need for continued research and debate around how we should restore post-war public spaces in order to meet the users’ needs and respect the spaces’ original design qualities. The findings also revealed that some of the original designed spaces are better used and valued than the retrofitted and new spaces. The findings showed that, despite the perceived limitations of the original designed spaces, they have a lot of qualities that are worth preserving and improving, as illustrated with the walkways. Their open qualities stand out as being key to making them sociologically open for different users’ needs.

These findings bring optimism to both national and international conservation and regeneration agendas. They demonstrate that post-war modernism heritage is actually increasingly valued, and this might be an indication that it is going through a reassessment and revalorisation away from the dominant discourses of failure. They also provide further evidence that, given the still challenging nature of post-war heritage and the obstacles that these pose to regenerating it, there is a need to continue to do more research that engages with the users’ experiences and uses.

Looking beyond the empirical study, this paper also makes an important contribution to the literature on post-war heritage and its reassessment. It provides a renewed understanding of post-war heritage value from a user perspective and the design qualities or features that must be preserved in order to achieve more inclusive conservation and regeneration. However, as the present study was focused on a single case study with its own specific social and political context, it asks caution against generalisation and knowledge transfer, as many projects elsewhere may have followed similar design principles as the SBC but may have been experienced and used differently.