In the Realm of Rain Gods: A Contextual Survey of Rock Art across the Northern Maya Lowlands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

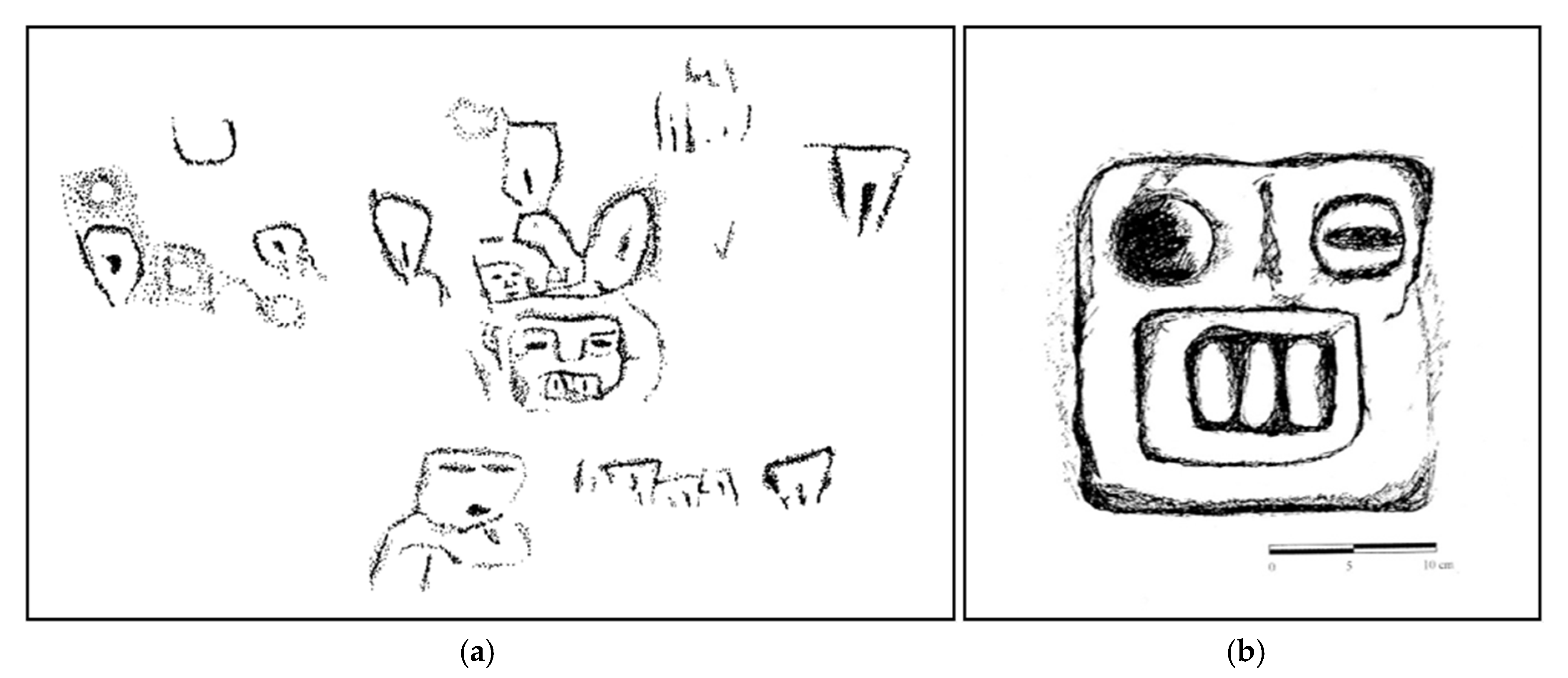

2. Frontal Faces

3. Rain Imagery

4. Sexual Imagery

5. Concluding Thoughts

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonor Villarejo, J.L. Las Cuevas Mayas: Simbolismo y Ritual; Universidad Compultense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, A. Images from the Underworld: Naj Tunich and the Tradition of Maya Cave Painting; University of Texas Press: Austin, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, A. Regional Variation in Maya Cave Art. J. Cave Karst Stud. 1997, 59, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E.H. Cave of Loltun; Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1897; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, A. The Painted Walls of Xibalba: Maya Cave Painting as Evidence of Cave Ritual. In Word and Image in Maya Culture: Explorations in Language, Writing, and Representation; Hanks, W.F., Rice, D.S., Eds.; University of Utah Press: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 1989; pp. 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, A. Actun Ch’on, Oxkutzcab, Yucatán: Una Cueva Maya con Pinturas del Clásico Tardío. Bol. Esc. Cienc. Antropol. Univ. Yucatán 1989, 16, 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Strecker, M. Cuevas Mayas en el Municipio de Oxkutzcab, Yucatán (I): Cuevas Mis y Petroglifos. Bol. Esc. Cienc. Antropol. Univ. Yucatán 1984, 68, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera Rubio, A.; Peraza Lope, C. Los vestigios pictóricos de la cueva de Tixcuytún, Yucatán. In Land of the Turkey and the Deer: Recent Research in Yucatan; Gubler, R., Ed.; Labyrinthos: Lancaster, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tec Pool, F.; Krempel, G. The Paintings of Aktun Santuario, Akil, Yucatan. Mexicon 2016, 38, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sayther, T.; Stuart, D.; Cobb, A. Pictographic Rock Art in Actun Kaua, Yucatan, Mexico. Am. Indian Rock Art 1998, 22, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Strecker, M. Cuevas Mayas en el Municipio de Oxkutzcab, Yucatán (II): Cuevas Ehbis, Xcosmil, y Cahum. Bol. Esc. Cienc. Antropol. Univ. Yucatán 1985, 70, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bonor Villarejo, J.L. Exploraciones en las Grutas de Calcehtok y Oxkintok, Yucatán, México. Mayab 1987, 33, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Uc González, E.; Canche Mazanero, E. Calcehtok desde la Perspectiva Arqueológica. In Memorias del Segundo Coloquio Internacional de Mayistas; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico, 1989; pp. 287–301. [Google Scholar]

- Bonor Villarejo, J.L.; Sánchez y Pinto, I. Las Cavernas del Municipio de Oxkutzkab, Yucatán, México: Nuevas Aportaciones. Mayab 1991, 7, 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rissolo, D. Ancient Maya Cave Use in the Yalahau Region, Northern Quintana Roo, Mexico, Bulletin 12; Association for Mexican Cave Studies: Austin, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.G. (Ed.) On the Edge of the Sea: Mural Painting at Tancah-Tulum, Quintana Roo, Mexico; Dumbarton Oaks: Washington, DC, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Rissolo, D. Beneath the Yalahau: Emerging Patterns of Ancient Maya Ritual Cave Use from Northern Quintana Roo, Mexico. In In the Maw of the Earth Monster: Mesoamerican Ritual Cave Use; Brady, J.E., Prufer, K.M., Eds.; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2005; pp. 342–372. [Google Scholar]

- Martos López, L.A. Investigaciones en la Costa Oriental: Punta Venado y La Rosita, Quintana Roo. Arqueología 1994, 11–12, 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Martos López, L.A. La Cueva de Aktunkoot, La Rosita, Quintana Roo; Informe de los trabajos de mapeo y exploración de la temporada 1992 y 1993 del Proyecto Arqueológico Calica; INAH: Mexico City, Mexico, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Martos López, L.A. Por las Tierras Mayas de Oriente: Arqueología en el Área de Calica; Calica-INAH: Mexico City, Mexico, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martos Lopez, L.A. Cuevas de la Region Central-Oriental de la Peninsula de Yucatan: Un Analisis desde la Perspectiva Simbolica. Ph.D. Thesis, Escuela Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, Mexico City, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lothrop, S.K. Tulum: An Archaeological Study of the East Coast of Yucatán; Publication 335; Carnegie Institution of Washington: Washington, D.C., USA, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- de Robina, R. Estudio Preliminar de las Ruinas de Hochob, Municipio de Hopelchen, Campeche; Editorial Atenea: Mexico City, Mexico, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Rissolo, D. Tancah Cave Revisited. AMCS Act. Newsl. 2005, 28, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, S.D. Classic Maya Depictions of the Built Environment. In Function and Meaning in Classic Maya Architecture; Houston, S.D., Ed.; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 333–372. [Google Scholar]

- Grove, D.C. Miscellaneous Bedrock and Boulder Carvings. In Ancient Chalcatzingo; Grove, D.C., Ed.; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1987; pp. 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Broda, J. Lenguaje Visual de Paisaje Ritual de la Cuenca de México. In Códices y Documentos Sobre México 2nd Simposio; Rueda, S., Vega, C., Martínez Baracs, R., Eds.; Colección Científica del INAH: Mexico City, Mexico, 1997; Volume II, pp. 129–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rissolo, D. Maya Cave Shrines along the Central Quintana Roo Coast. AMCS Act. Newsl. 2004, 27, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Devos, F.; CINDAQ, Puerto Aventuras, Quintana Roo, Mexico City, Mexico. Personal Communication, 14 August 2020.

- Strecker, M. Representaciones de manos y pies en el arte rupestre de cuevas de Oxkutzcab, Yucatán. Bol. Esc. Cienc. Antropol. Univ. Yucatán 1982, 52, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tec Pool, F. Distribución y Contexto de las Pictografías en Kanun Ch’en, Homún, Yucatán. Mundos Subterráneos 2012, 22–23, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rissolo, D. El Arte Rupestre de Quintana Roo. In Arte Rupestre de México Oriental y Centro América; Künne, M., Strecker, M., Eds.; Indiana Beihefte. Gebr. Mann Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2003; Volume 16, pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Moyes, H. Constructing the Underworld: The Built Environment in Ancient Mesoamerican Caves. In Heart of Earth: Studies in Maya Ritual Cave Use; Bulletin Series No. 23; Brady, J.E., Ed.; Association for Mexican Cave Studies: Austin, TX, USA, 2012; pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rissolo, D.; Hess, M.R.; Hoff, A.R.; Meyer, D.; Amador, F.E.; Velazquez Morlet, A.; Petrovic, V.; Kuester, F. Imaging and Visualizing Maya Cave Shrines in Northern Quintana Roo, Mexico. In Proceedings of the 8th International Congress on Archaeology, Computer Graphics, Cultural Heritage and Innovation, Valencia, Spain, 5–7 September 2016; Editorial Universitat Politecnica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2016; pp. 382–384. [Google Scholar]

- Rissolo, D.; Lo, E.; Hess, M.R.; Meyer, D.E.; Amador, F.E. Digital Preservation of Ancient Maya Cave Architecture: Recent Field Efforts in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W5, 613–616. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, D.A. Into the Heart of the Turtle: Caves, Ritual, and Power in Ancient Central Yucatan, Mexico. Ph.D. Thesis, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moyes, H.; Awe, J.J. Belize Regional Cave Project: Report of the 2015 Field Season; National Institute of Culture and History: Belmopan, Belize, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, C.G.B.; Awe, J.J. Preliminary Analysis of the Pictographs, Petroglyphs, and Sculptures of Actun Uayazba Kab, Cayo District, Belize. In The Western Belize Regional Cave Project: A Report of the 1997 Field Season; Department of Anthropology Occasional Paper No. 1; Awe, J.J., Ed.; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 1998; pp. 141–199. [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, C.G.B.; Awe, J.J.; Griffith, C.S. El Arte Rupestre de Belice. In Arte Rupestre de México Oriental y Centro América; Künne, M., Strecker, M., Eds.; Indiana Beihefte. Gebr. Mann Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2003; Volume 16, pp. 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Moyes, H.; University of California, Merced, Merced, CA, USA. Personal Communication, 13 September 2020.

- Astor-Aguilera, M.; Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. Personal Communication, 2 March 2001.

- Houston, S.D.; Stuart, D. T632 as Muyal, “Cloud.”. Cent. Tennessean Notes Maya Epigr No.1. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, A. The Cleveland Plaque: Cloudy Places of the Maya Realm. In VIII Palenque Round Table 1993; Robertson, M.G., Macri, M., McHargue, J., Eds.; Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, F.K., III. The Lazy-S: A Formative Period Iconographic Loan to Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. In VIII Palenque Round Table 1993; Robertson, M.G., Macri, M., McHargue, J., Eds.; Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 413–424. [Google Scholar]

- Villacorta, C.J.A.; Villacorta, C.A. Codices Mayas; Tipografía Nacional: Guatemala City, Guatemala, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Angulo, V.J. The Chalcatzingo Reliefs: An Iconographic Analysis. In Ancient Chalcatzingo; Grove, D.C., Ed.; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1987; pp. 132–158. [Google Scholar]

- Villela, F.S.L. Nuevo Testimonio Rupestre Olmeca en el Oriente de Guerrero. Arqueología 1989, 2, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera Rubio, A. The Rain Cult of the Puuc Area. In Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980; Palenque Round Table Series 4; Benson, E.P., Ed.; Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985; pp. 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera Rubio, A. Obras Hidraulicas en la Region Puuc, Yucatán, México. Bol. Esc. Cienc. Antropol. Univ. Yucatán 1987, 15, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata Peraza, R.L. El Uso del Agua y los Mayas Antiguos: Algunos Ejemplos Arqueológicos de Campeche. Bol. Esc. Cienc. Antropol. Univ. Yucatán 1987, 15, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata Peraza, R.L. Los Chultunes: Sistemas de Capitación de Agua Pluvial; Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia: Mexico City, Mexico, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Spranz, B. Descubrimiento en Totimehuacan, Puebla. Boletin Del INAH 1967, 28, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Manzanilla, L. The Construction of the Underworld in Central Mexico: Transformations from the Classic to the Postclassic. In Mesoamerica’s Classic Heritage: From Teotihuacan to the Aztecs; Carrasco, D., Jones, L., Sessions, S., Eds.; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2000; pp. 87–116. [Google Scholar]

- Taube, K.A. The Major Gods of Ancient Yucatan; Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology, No. 32; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Strecker, M.; Stone, A. El Arte Rupestre de Yucatán y Campeche. In Arte Rupestre de México Oriental y Centro América; Indiana Beihefte; Künne, M., Strecker, M., Eds.; Gebr. Mann Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2003; Volume 16, pp. 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Taube, K.A.; University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA, USA. Personal Communication, 1 June 1999.

- Strecker, M. Representaciones Sexuales en el Arte Rupestre de la Región Maya. Mexicon 1987, 9, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, J.E.; Stone, A. Naj Tunich: Entrance to the Maya Underworld. Archaeology 1986, 39, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, A. The Moon Goddess at Naj Tunich. Mexicon 1985, 7, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, J.E. The Sexual Connotation of Caves in Mesoamerican Ideology. Mexicon 1988, 10, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, A. Commentary. Mexicon 1987, 9, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolides, A. Chalcatzingo Painted Art. In Ancient Chalcatzingo; Grove, D.C., Ed.; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1987; pp. 171–199. [Google Scholar]

- Strecker, M. Pinturas Rupestres de la Cueva de Loltún. Boletín Del INAH. 1976, 18, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez Morlet, A.; López de la Rosa, E.; Casado López, M.; del P. Gaxiola, M. Zonas Arqueológicas: Yucatán; Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia: Mexico City, Mexico, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tec Pool, F. Representaciones pictográficas en la cueva de Aktun K’ab, en Kahua, Yucatán. In XXII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, Guatemala City, Guatemala, 21–25 July 2008; Laporte, J.P., Arroyo, B., Mejía, H., Eds.; Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: Guatemala City, Guatemala, 2009; pp. 1328–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Veni, G. The Mayan Maze of Actun Kaua. AMCS Act. Newsl. 2003, 26, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, E.W., IV; Andrews, A.P. A Preliminary Study of the Ruins of Xcaret, Quintana Roo, Mexico: With Notes on Other Archaeological Remains on the Central East Coast of the Yucatán Peninsula; Publication 40; Middle American Research Institute: New Orleans, LA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Terrones, E.; Leira, L. Plano de la Cueva Grupo Y de Xcaret, Proyecto Punta Piedra; Archivo del Centro INAH Quintana Roo: Chetumal, Mexico, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews IV, E.W. Balankanche, Throne of the Tiger Priest; Publication 32; Middle American Research Institute: New Orleans, LA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, J.L. Incidents of Travel in Yucatan; Harper and Rowe: New York, NY, USA, 1843. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, N.P.; Weaver, E.; Smyth, M.P.; Ortegón Zapata, D. Xcoch: Home of Ancient Maya Rain Gods and Water Managers. In The Archaeology of Yucatan; Stanton, T.W., Ed.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, W.M.; Bey, G.J., III; Gallareta Negrón, T. A New Monument from Huntichmul, Yucatan, Mexico, Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing No. 57; Boundary End Archaeological Research Center: Barnardsville, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rissolo, D. In the Realm of Rain Gods: A Contextual Survey of Rock Art across the Northern Maya Lowlands. Heritage 2020, 3, 1094-1108. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3040061

Rissolo D. In the Realm of Rain Gods: A Contextual Survey of Rock Art across the Northern Maya Lowlands. Heritage. 2020; 3(4):1094-1108. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3040061

Chicago/Turabian StyleRissolo, Dominique. 2020. "In the Realm of Rain Gods: A Contextual Survey of Rock Art across the Northern Maya Lowlands" Heritage 3, no. 4: 1094-1108. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3040061

APA StyleRissolo, D. (2020). In the Realm of Rain Gods: A Contextual Survey of Rock Art across the Northern Maya Lowlands. Heritage, 3(4), 1094-1108. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3040061