The Contradictions of Engaged Archaeology at Punta Laguna, Yucatan, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Contradictions and Engaged Archaeology

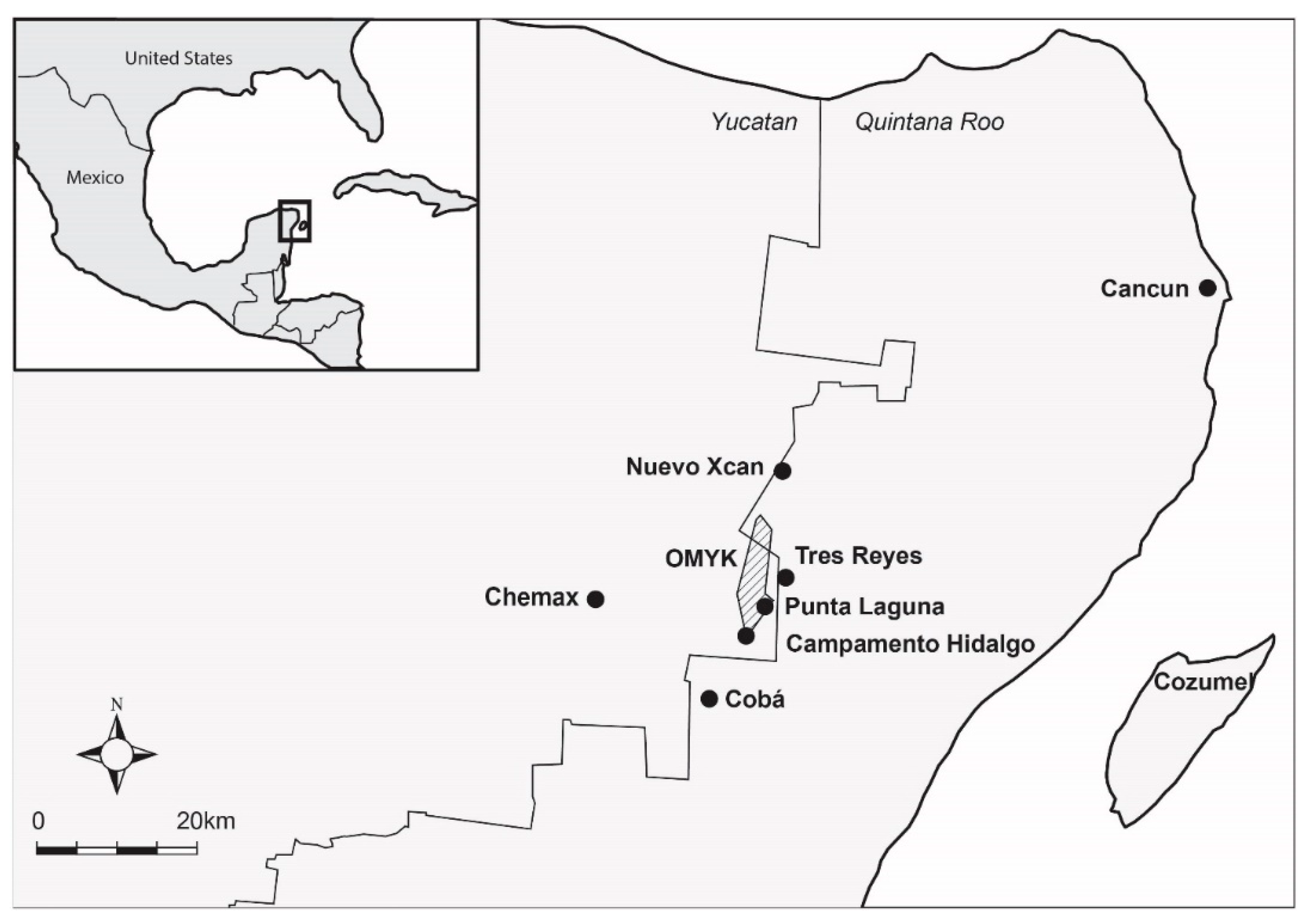

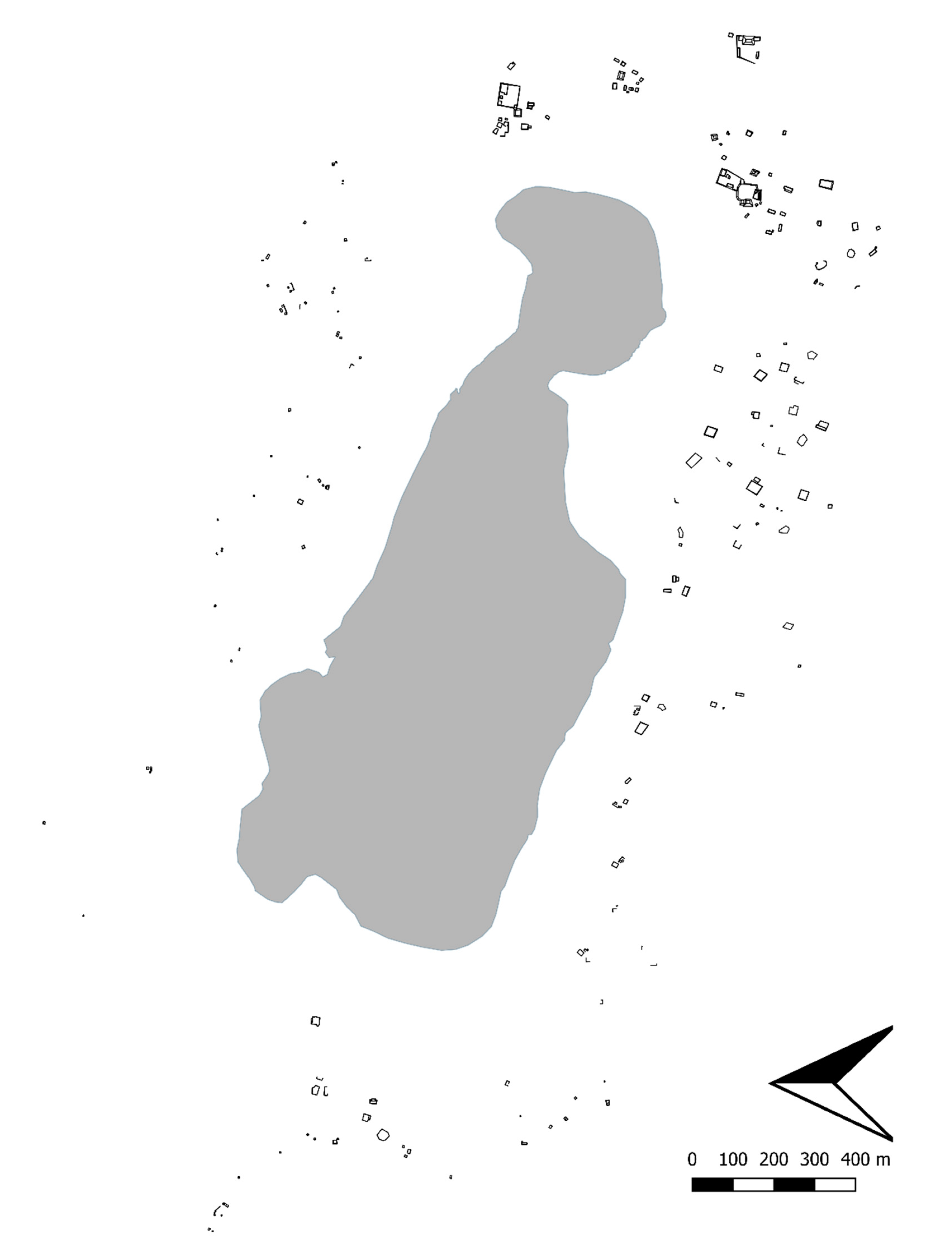

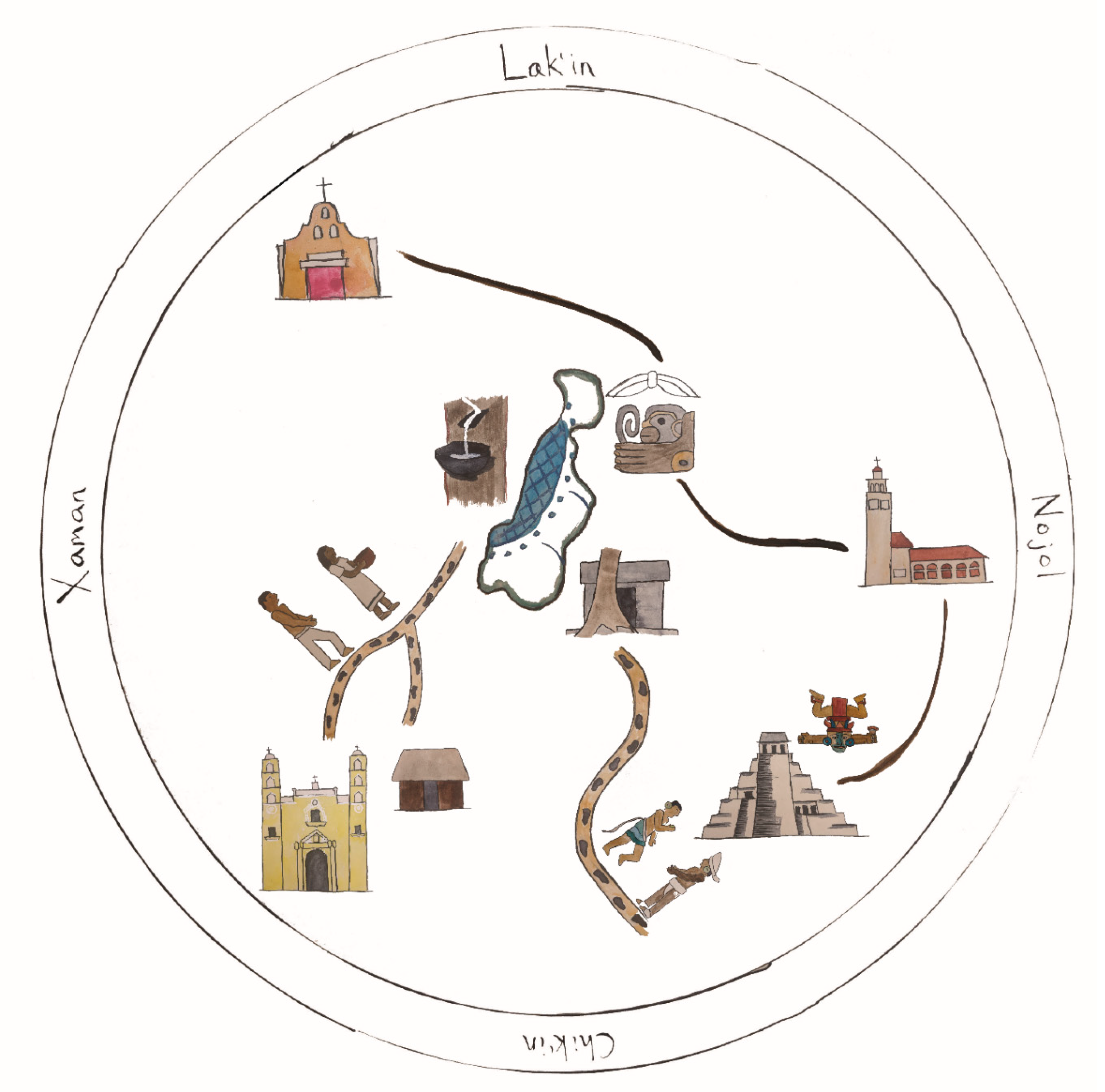

3. The Maya Area, Punta Laguna, and the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project

4. The Contradictions of Labor

5. The Contradictions of Capital

6. The Contradictions of Praxis

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hegel, G.W.F. The Science of Logic; Cambridge Hegel Translations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sayers, S. Contradiction and Dialectic in the Development of Science. Sci. Soc. 1981, 45, 409–436. [Google Scholar]

- Chesson, M.S.; Ullah, I.I.T.; Iiriti, G.; Forbes, H.; Lazrus, P.K.; Ames, N.; Garcia, Y.; Benchekroun, S.; Robb, J.; Wolff, N.P.S.; et al. Archaeology as Intellectual Service: Engaged Archaeology in San Pasquale Valley, Calabria, Italy. Archaeologies 2019, 15, 422–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S.; Clauss, L.R.; McGuire, R.H.; Welch, J.R. Transforming Archaeology. In Transforming Archaeology: Activist Practices and Prospects; Atalay, S., Clauss, L.R., McGuire, R.H., Welch, J.R., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sabloff, J.A. Archaeology Matters: Action Archaeology in the Modern World; Left Coast: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-59874-089-9. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, S. Community-Based Archaeology: Research With, By, and For Indigenous and Local Communities; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Y. What is community archaeology? World Archaeol. 2002, 34, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S. Indigenous Archaeology as Decolonizing Practice. Am. Indian Q. 2006, 30, 280–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J. Indigenous Archaeology: American Indian Values and Scientific Practice; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7591-1709-9. [Google Scholar]

- McAnany, P.A.; Rowe, S.M. Re-visiting the field: Collaborative archaeology as paradigm shift. J. Field Archaeol. 2015, 40, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, C. Foreword. In Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship; Hale, C.R., Ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008; pp. xiii–xxvi. [Google Scholar]

- Moberg, M. Engaging Anthropological Theory: A Social and Political History; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel, G.W.F. Dialectics. In Literary Theory: An Anthology; Rivkin, J., Ryan, M., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 647–649. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K.; Engels, F. Manifesto of the Communist Party; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K.; Engels, F. The German Ideology; Arthur, C.J., Ed.; International Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, M. Marxism and Anthropology: The History of a Relationship; Routledge Library Editions—Anthropology and Ethnography; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Outline of a Theory of Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977; ISBN 978-0-521-29164-4. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, R.B. Whatever Happened to the Stone Age? Steel Tools and Yanomami Historical Ecology. In Advances in Historical Ecology; Balée, W., Ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 287–312. [Google Scholar]

- Balée, W. Historical Ecology: Premises and Postulates. In Advances in Historical Ecology; Balée, W., Ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure Of Scientific Revolutions, 3rd ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Binford, L.R.; Sabloff, J.A. Paradigms, Systematics, and Archaeology. J. Anthropol. Res. 1982, 38, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G. The paradigm concept in archaeology. World Archaeol. 2017, 49, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, D.J. Paradigms and the Nature of Change in American Archaeology. Am. Antiq. 1979, 44, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqardt, W.H. Dialectical Archaeology. Archaeol. Method Theory 1992, 4, 101–140. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, R.H. Archaeology and Marxism. Archaeol. Method Theory 1993, 5, 101–157. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, R.H. A Marxist Archaeology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, R.H.; Saitta, D.J. Although They Have Petty Captains, They Obey Them Badly: The Dialectics of Prehispanic Western Pueblo Social Organization. Am. Antiq. 1996, 61, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, R.H.; Wurst, L. Struggling with the Past. Int. J. Hist. Archaeol. 2002, 6, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spriggs, M. Another Way of Telling: Marxist Perspectives in Archaeology. In Marxist Perspectives in Archaeology; Spriggs, M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, C. Ideology and the Legitimation of Power in the Middle Neolithic of Southern Sweden. In Ideology, Power and Prehistory; Miller, D., Tilley, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; pp. 111–146. [Google Scholar]

- Trigger, B.G. Marxism in Contemporary Western Archaeology. Archaeol. Method Theory 1993, 5, 159–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kurnick, S. Paradoxical Politics: Negotiating the Contradictions of Political Authority. In Political Strategies in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica; Kurnick, S., Baron, J., Eds.; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rautman, A.E. Hierarchy and heterarchy in the American Southwest: A comment on McGuire and Saitta (1996). Am. Antiq. 1998, 63, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, D.J.; McGuire, R.H. Dialectics, Heterarchy, and Western Pueblo Social Organization. Am. Antiq. 1998, 63, 334–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McAnany, P.A. Maya Cultural Heritage: How Archaeologists and Indigenous Communities Engage the Past; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4422-4128-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, C.R. Introduction. In Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship; Hale, C.R., Ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tuhiwai Smith, L. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples; Zed Books Ltd: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Conkey, M.W. Dwelling at the Margins, Action at the Intersection? Feminist and Indigenous Archaeologies, 2005. Archaeologies 2005, 1, 9–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, G. Silver Cities of Yucatan; G.P. Putnam’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, W.R. Tikal: A Handbook of the Ancient Maya Ruins, 2nd ed.; The University Museum: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McAnany, P.A.; Parks, S. Casualties of Heritage Distancing: Children, Ch’orti’ Indigeneity, and the Copán Archaeoscape. Curr. Anthropol. 2012, 53, 80–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, S.; McAnany, P.A.; Murata, S. The Conservation of Maya Cultural Heritage: Searching for Solutions in a Troubled Region. J. Field Archaeol. 2006, 31, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, R.M.; Chan Espinosa, C.; Moo Pat, E.; Poot Cahun, D. The Community Heritage Project in Tihosuco, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Public Archaeol. 2014, 13, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardren, T. Conversations about the Production of Archaeological Knowledge and Community Museums at Chunchucmil and Kochol, Yucatán, México. World Archaeol. 2002, 34, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ardren, T. Where Are the Maya in Ancient Maya Archaeological Tourism? Advertising and the Appropriation of Culture. In Marketing Heritage: Archaeology and the Consumption of the Past; Rowan, Y., Baram, U., Eds.; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Alvarez, H.; Martín Medina, G.G. Arqueología colaborativa y recuperación de la memoria histórica: Hacienda San Pedro Cholul, Yucatán. Temas Antropológicos Rev. Científica Investig. Reg. 2016, 38, 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kurnick, S. Creating Nature in the Yucatan Peninsula: Social Inequality and the Production of Eco-Archaeological Parks. Am. Anthropol. 2019, 121, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Sandoval, C. Cementerios Acuáticos Mayas. Arqueol. Mex. 2007, 14, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Sandoval, C. Prácticas Mortuorias En Los Cenotes. Rev. Arqueol. Am. 2008, 26, 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Sandoval, C. Tratamientos Mortuorios en los Cenotes. Arqueol. Mex. 2010, 18, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Sandoval, C.; Gonzales Gonzales, A.H.; Terrazas Mata, A.; Benavente San Vicente, M. Mayan Mortuary Deposits in the Cenotes of Yucatan and Quintana Roo, Mexico. In Underwater and Maritime Archaeology in Latin America and the Caribbean; Leshikar-Denton, M.E., Erreguerena, P.L., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 143–153. ISBN 1-59874-262-0. [Google Scholar]

- Martos López, L.A. Underwater Archaeological Exploration of the Mayan Cenotes. Mus. Int. 2008, 60, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasdefer, F.C. Archaeological Notes from Quintana Roo. Mexicon 1988, 10, 107–108. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides Castillo, A.; Zapata Peraza, R.L. Punta Laguna: Un Sitio Prehispánico de Quintana Roo. Estud. Cult. Maya 1991, XVIII, 23–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kurnick, S. Navigating the past in the aftermath of dramatic social transformations: Postclassic engagement with the Classic period past in the northeast Yucatan peninsula. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2019, 53, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnick, S.; Rogoff, D. Final Report of the 2014 Field Season of the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project; Report Submitted to the Gerda Henkel Foundation; Gerda Henkel Foundation: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kurnick, S.; Rogoff, D. Final Report on the 2015–2016 Season of the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project; Report Submitted to the National Geographic Society; National Geographic Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Robles Castellanos, J.F. La Secuencia Cerámica de la Región de Cobá, Quintana Roo; Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia: Ciudad de México, México, 1990.

- Ancona Aragon, I.; Jiménez Álvarez, S.; Martínez Garrido, M.G.; Bonilla Medina, C. Análisis Cerámico de Punta Laguna, Quintana Roo. In Proyecto Arqueológico Punta Laguna: Informe Parcial de la Temporada 2019 para el Consejo Nacional de Arqueología de México; Kurnick, S., Rogoff, D., Eds.; A Technical Report Submitted to the Mexican Government; Mexican Government: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy; Engels, F., Ed.; Progress Publishers: Moscow, Russia, 1887; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. Wage Labour and Capital; Neue Rheinische Zeitung: Cologne, Germany, 1891. [Google Scholar]

- Kurnick, S. The Origins of Extreme Economic Inequality: An Archaeologist’s Take on a Contemporary Controversy. Archaeologies 2015, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.E. Complex Hunter-Gatherer-Fishers of Prehistoric California: Chiefs, Specialists, and Maritime Adaptations of the Channel Islands. Am. Antiq. 1992, 57, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.E. Social Inequality, Marginalization, and Economic Process. In Foundations of Social Inequality; Price, T.D., Feinman, G.M., Eds.; Fundamental Issues in Archaeology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 87–103. ISBN 978-1-4899-1291-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, T. Conjunctures in the Making of an Ancient Maya Archaeological Site. In Ethnographies of Archaeological Practice: Cultural Encounters, Material Transformations; Edgeworth, M., Ed.; AltaMira Press: LanhaM, MD, USA, 2006; pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Breglia, L. When Patrimonies Collide: The Case of Chunchucmil, Yucatán. In Ethnographies and Archaeologies: Iterations of the Past; Mortensen, L., Hollowell, J., Eds.; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2009; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, D. The ethics of archaeology, subsistence digging, and artifact looting in Latin America: Point muted counterpoint. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 1998, 7, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, G.; Hollowell, J. Ethical Challenges to a Postcolonial Archaeology: The Legacy of Scientific Colonialism. In Archaeology and Capitalism: From Ethics to Politics; Hamilakis, Y., Duke, P., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wesp, J.K.; Ivone Ku, M.Y.; Haun, M.; Ku Rodriguez, M.E.; Ardren, T.; Moo Ku, D.M. İNos Rebelamos! Negotiating women’s work in the midst of power, socio-economic need, and heritage in Yucatan today. In Proceedings of the 10o Congreso Internacional de Mayistas, Yucatán, Mexico, 26 July–1 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. Capital, Volume I; Electric Book Company: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-1-84327-097-3. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 1st ed.; Belknap Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-674-43000-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- The Archaeology of Capitalism in Colonial Contexts: Postcolonial Historical Archaeologies; Croucher, S.K., Weiss, L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4614-0192-6. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, M.P. A Historical Archaeology of Capitalism. Am. Anthropol. 1995, 97, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contributions to Global Historical Archaeology. In Historical Archaeologies of Capitalism, 2nd ed.; Leone, M.P., Knauf, J.E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-12759-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, G.; Hreiðarsdóttir, E. The Archaeology of Capitalism in Iceland: The View from Viðey. Int. J. Hist. Archaeol. 2012, 16, 604–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T.C. The Political Economy of Archaeology in the United States. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1999, 28, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilakis, Y. From Ethics to Politics. In Archaeology and Capitalism: From Ethics to Politics; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilakis, Y. Archaeology and the Logic of Capital: Pulling the Emergency Break. Int. J. Hist. Archaeol. 2015, 19, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, C.J. Heritage or Heresy: Archaeology and Culture on the Maya Riviera; The University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, A. Commodifying the Indigenous in the Name of Development: The Hybridity of Heritage in the Twenty-First Century Andes. Public Archaeol. 2014, 13, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberman, N.A. ‘Sustainable’ Heritage? Public Archaeological Interpretation and the Marketed Past. In Archaeology and Capitalism: From Ethics to Politics; Hamilakis, Y., Duke, P., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.R. Maya Cosmopolitans: Everyday Life at the Interface of Archaeology, Heritage, and Tourism Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, SUNY Albany, Albany, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.R. On Being Maya and Getting By: Heritage Politics and Community Development in Yucatán; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-60732-772-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism and Archaeology: Sustainable Meeting Grounds; Walker, C., Carr, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, J.A. Colonizing space and commodifying place: Tourism’s violent geographies. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Rodríguez, R. Mexico for Sale: The Manipulation of Cultural Heritage for Tourism Purposes: The Case of the Xcaret Night Show. In The Making of Heritage: Seduction and Disenchantment; del Mármol, C., Morell, M., Chalcraft, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 120–139. [Google Scholar]

- Magnoni, A.; Ardren, T.; Hutson, S. Tourism in the Mundo Maya: Inventions and (Mis)Representations of Maya Identities and Heritage. Archaeol. J. World Archaeol. Congr. 2007, 3, 353–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, M. The Archaeology of Liberty in an American Capital: Excavations in Annapolis; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-520-93189-3. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, R.H.; O’Donovan, M.; Wurst, L. Probing Praxis in Archaeology: The Last Eighty Years. Rethink. Marx. 2005, 17, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Andreu, M. Ethics and Archaeological Tourism in Latin America. Int. J. Hist. Archaeol. 2013, 17, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R. Commodification, culture and tourism. Tour. Stud. 2002, 2, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, B.; Chatzoglou, A.; Taha, S. Packaging the Past: The Commodification of Heritage. Herit. Manag. 2010, 3, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, R.H. Archaeology as Political Action; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-520-25490-9. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K.; Engels, F. Theses on Feuerbach. In Marx/Engels Selected Works; Progress Publishers: Moscow, Russia, 1969; Volume 1, pp. 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Preucel, R.; Cipolla, C. Archaeology and the Postcolonial Critique; Liebmann, M., Rizvi, U.Z., Eds.; Archaeology in Society Series; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-7591-1004-5. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.; Wobst, H.M. Indigenous Archaeologies: Decolonising Theory and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-134-39155-4. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, C.; Ferguson, T.J.; Gann, D. Multivocality in Multimedia: Collaborative Archaeology and the Potential of Cyberspace. In New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology; Okamura, K., Matsuda, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, W.; Somerville, M. Conversations between disciplines: Historical archaeology and oral history at Yarrawarra. World Archaeol. 2005, 37, 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, E. The Materialities of Place Making in the Ancient Andes: A Critical Appraisal of the Ontological Turn in Archaeological Interpretation. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2015, 22, 677–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, B. Archaeologies of Ontology. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2016, 45, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, B.; Fowles, S.; Holbraad, M.; Marshall, Y.; Witmore, C. Archaeology, Anthropology, and Ontological Difference: Archaeology, Anthropology, and Ontological Difference. Curr. Anthropol. 2011, 52, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNiven, I.J. Theoretical Challenges of Indigenous Archaeology: Setting an Agenda. Am. Antiq. 2016, 81, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silliman, S.W. Collaborating at the Trowel’s Edge: Teaching and Learning in Indigenous Archaeology; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-8165-2722-9. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Y.; Alberti, B. A Matter of Difference: Karen Barad, Ontology and Archaeological Bodies. Camb. Archaeol. J. 2014, 24, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.A.; Walker, W.H. Prologue: Archaeology, Animism and Non-Human Agents. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2008, 15, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacred Matter: Animacy and Authority in the Americas; Kosiba, S., Janusek, J.W., Cummins, T.B.F., Eds.; Dumbarton Oaks: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-88402-466-8. [Google Scholar]

- Stump, D. On Applied Archaeology, Indigenous Knowledge, and the Usable Past. Curr. Anthropol. 2013, 54, 268–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, Z. An Indigenous Feminist’s Take on The Ontological Turn: “Ontology” Is Just Another Word for Colonialism. J. Hist. Sociol. 2016, 29, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnick, S.; Rogoff, D. Maya Cartographies: Two Maps of Punta Laguna, Yucatan, Mexico. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Philips, S.U. Language and Social Inequality. In A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology; Duranti, A., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 474–495. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurnick, S. The Contradictions of Engaged Archaeology at Punta Laguna, Yucatan, Mexico. Heritage 2020, 3, 682-698. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3030039

Kurnick S. The Contradictions of Engaged Archaeology at Punta Laguna, Yucatan, Mexico. Heritage. 2020; 3(3):682-698. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3030039

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurnick, Sarah. 2020. "The Contradictions of Engaged Archaeology at Punta Laguna, Yucatan, Mexico" Heritage 3, no. 3: 682-698. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3030039

APA StyleKurnick, S. (2020). The Contradictions of Engaged Archaeology at Punta Laguna, Yucatan, Mexico. Heritage, 3(3), 682-698. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3030039