Museum Practices as Tools to (Re)Define Memory and Identity Issues Through Direct Experience of Tangible and Intangible Heritage

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Gdańsk

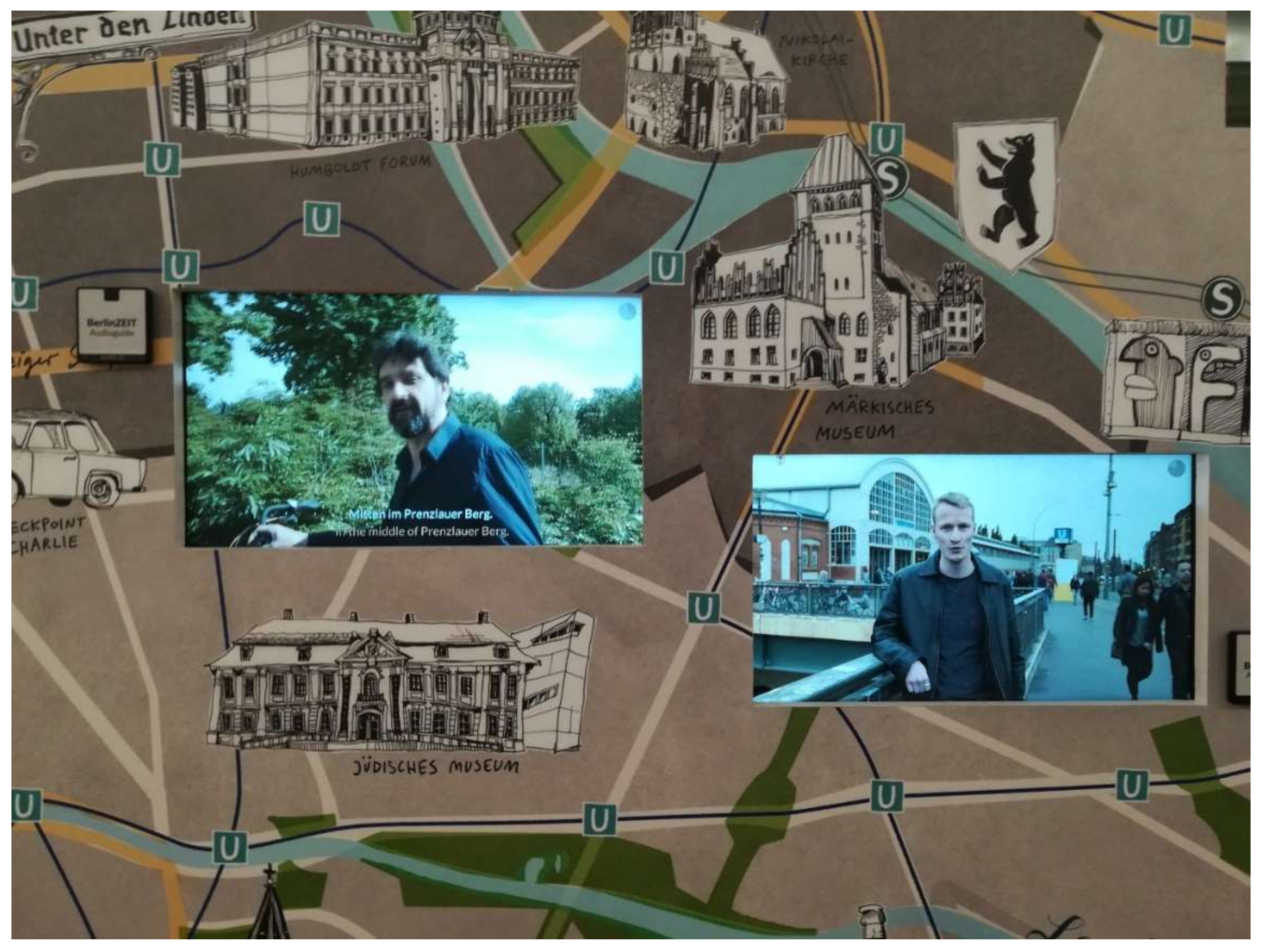

3.2. Berlin

4. Discussion

- -

- the comtemporalization paradigm: if museums represent certain structures, by which their main functions preserve and explain certain heritage in an orderly way to enhance and encourage the identification with it, then the language of this communication should be adjusted to the current expectations of those to whom the message is delivered. It can be done so by using new media and technologies, although one should bear in mind their auxiliary role towards the original objects of the museums’ collections, rather than entertaining substitutes;

- -

- the social paradigm: is very much connected with the comtemporalization paradigm, as it negotiates the museums’ narrations (that is, the way they communicate their stories/narratives) with the needs and expectations of their contemporary audiences. It is based on the strategy of inclusion, by addressing issues which incorporate into the museum narratives the representatives of different social backgrounds together with their personal cultural identities as well as both tangible and intangible heritage they represent;

- -

- the interdisciplinary paradigm: the discussion over the final shape of the museum exhibition and the narrative (the story) behind it, may be supported by combining various research methodologies. Entrusting the design of the exhibitions to the representatives of different fields of knowledge, including scientists of multiple fields representing comprehensive academic expertise, together with artists providing the practical hands-on solutions based on high level creativity, social sensitivity and innovative perspectives, as well as cultural workers who constitute the real bond between the institution and its audience established on a regular everyday basis, would surely provide all-round solutions addressing all three paradigms listed here. Above all, it would provide a fresh democratic and complex view on the multiplicity of tasks the contemporary museums should undertake.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Żygulski, Z., Jr. Muzea na Świecie. Wstęp do Muzealnictwa [Museums of the World, Introduction to Museum Studies]; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. (Ed.) Nieco płynnych myśli o sztuce w płynie [Some liquid thoughts on the liquid art]. In Między Chwilą a Pięknem o Sztuce w Rozpędzonym Świecie [Between an Instant and Beauty: On Art in the Speeding World]; Żakowski, M., Translator; Officyna: Łódź, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, T. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barańska, K. Vita magistra Historiae est. O zarządzaniu historią w muzeach. [Vita magistra historiae est. On history management in museums]. In Historia w muzeum. Muzeum. Formy i środki prezentacji [History in Museum. Museum. Forms and Means of Presentation]; Woźniak, M.F., De Rosset, T.F., Ślusarczyk, W., Eds.; Muzeum Okręgowe im. Leona Wyczółkowskiego in Bydgoszcz and Narodowy Instytut Muzealnictwa i Ochrony Zabytków: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2013; Volume I, pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, A. Wprowadzenie: o krytyce, popularności i adekwatności terminu „pamięć” [Introduction: on the criticism, popularity and adequacy of the term „memory”]. In Między Historią a Pamięcią. Antologia [Between History and Memory: Anthology]; Saryusz-Wolska, M., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego (WUW): Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, J. Pamięć Kulturowa. Pismo, Zapamiętywanie i Polityczna Tożsamość w Cywilizacjach Starożytnych, [Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination]; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, P. Entre Mémoire et Histoire. La problématique des lieux. In Les Lieux de Mémoire; Nora, P., Ed.; „La République“, Éditions Gallimard: Paris, France, 1984; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Płynne Czasy. Życie w Epoce Niepewności [Liquid Times. Life in the Times of Uncertainty]; Żakowski, M., Translator; Sic!: Warszawa, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Macdoland, S. Memorylands. Heritage and Identity in Europe Today; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Karkowska, M. Pamięć Kulturowa Mieszkańców Olsztyna la$t 1945–2006 w Perspektywie Koncepcji Aleidy i Jana Assmannów [Cultural Memory of Inhabitants of Olsztyn between 1945 and 2006 in the Perspective of Aleida and Jan Assmann Concept]; Wydawnictwo IFiS PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ostow, R. Introduction: Museums and National Identities in Europe in the Twenty-First Century. In Revisualizing National History; Ostow, R., Ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, J. Odbudowa Głównego Miasta w Gdańsku w Latach 1945–1960 [Reconstruction of the Main Town in Gdańsk in the Years 1945–1960]; słowo/obraz/terytoria: Gdańsk, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, M. Ochrona dziedzictwa kulturowego, a muzea Pomorza Nadwiślańskiego [The protection of cultural heritage, and museums of Pomorze Nadwiślańskie]. In Muzea, a Dziedzictwo Kulturowe Pomorza, Proceedings of the Materiały Konferencji Jubileuszowej Wejherowo 24 X 1998 [Museums and Cultural Heritage of Pomerania, Materials from Conference in Wehjerowo 24 X 1998]; Borzyszkowski, J., Ed.; MPiMK-P and IK: Gdańsk, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, S. Theorizing museums: An introduction. In Theorizing Museums. Representing Identity and Diversity in a Changing World; Macdonald, S., Fyfe, G., Eds.; The Sociological Review; Blackwell Publishers: British, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Majewski, P. Narracja historyczna w museum—Cenzura czy „polityk kulturalna”? [Historical narration in museum—Censorship or „cultural policy”?]. In Historia w Muzeum. Muzeum. Formy i Środki Prezentacji [History in Museum. Museum. Forms and Means of Presentation]; Woźniak, M.F., De Rosset, T.F., Ślusarczyk, W., Eds.; Muzeum Okręgowe im. Leona Wyczółkowskiego in Bydgoszcz and Narodowy Instytut Muzealnictwa i Ochrony Zabytków: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2013; Volume I, pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Szumny, M. 7 Rzeczy, Które Musicie Wiedzieć o Muzeum II Wojny Światowej. ‘Całe Zło Ukryte Jest Pod Ziemią’ [7 Things Which You have to Know about the Museum of II World War. ‘The Entire Evil is Hidden Underground’]. Available online: https://pomorskie.eu/-/7-rzeczy-ktore-musicie-wiedziec-o-muzeum-ii-wojny-swiatowej-cale-zlo-ukryte-jest-pod-ziemia- (accessed on 16 November 2018).

- Machcewicz, P. Po co nam Muzeum II Wojny Światowej [Why do we need Museum of the Second World War]. In Muzeum II Wojny Światowej, Katalog Wystawy Głównej [The Museum of II World War, the Main Exhibition Catalogue]; Museum of WWII,: Gdańsk, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, N. Germany: Memories of a Nation; Allen Lane: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.stadtmuseum.de/humboldt-forum (accessed on 21 July 2018).

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wróblewska, M. Museum Practices as Tools to (Re)Define Memory and Identity Issues Through Direct Experience of Tangible and Intangible Heritage. Heritage 2019, 2, 2408-2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030148

Wróblewska M. Museum Practices as Tools to (Re)Define Memory and Identity Issues Through Direct Experience of Tangible and Intangible Heritage. Heritage. 2019; 2(3):2408-2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030148

Chicago/Turabian StyleWróblewska, Marta. 2019. "Museum Practices as Tools to (Re)Define Memory and Identity Issues Through Direct Experience of Tangible and Intangible Heritage" Heritage 2, no. 3: 2408-2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030148

APA StyleWróblewska, M. (2019). Museum Practices as Tools to (Re)Define Memory and Identity Issues Through Direct Experience of Tangible and Intangible Heritage. Heritage, 2(3), 2408-2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030148