1. Introduction: Büyükada Throughout History

Büyükada, which is isolated from the mainland, represents a special character and islandscape formation that constitutes a prominent example of natural, economical, socio-cultural, and architectural qualities. Since the relationship between the social and economic environment is especially strong and balanced between the size of the population and the resources on the Island, this isolated piece of land of unique and authentic identities has drawn attention from the past to the present and has left a noticeable trace in the urban memory.

As a satellite settlement of Istanbul, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, and later the capital of the Ottoman Empire, Büyükada has borne witness to historical, religious, and political events for more than 2000 years. This multi-layered culture gives Büyükada its unique character, which is further enriched by architectural masterpieces that shape its distinctive silhouette.

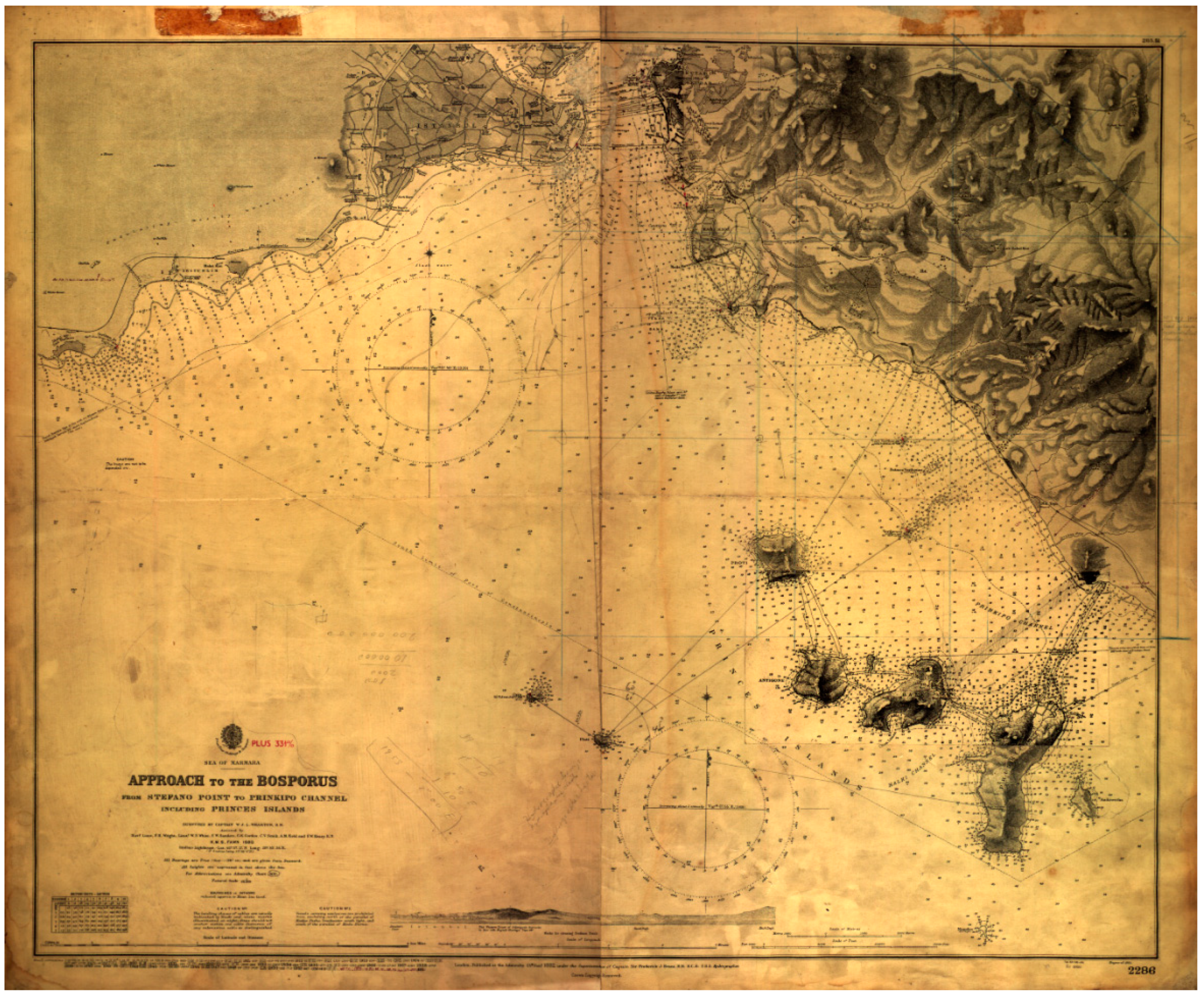

The nine islands of the Istanbul Archipelago (

Figure 1) are collectively known as the “Princes’ Islands” or “Les Iles Des Saints” (Hammer, 1822 [

1]) because of the aristocrats, princes, patriarchs, priests, and emperors who have lived there in self-imposed or forced exile throughout history (Schlumberger, 2006 [

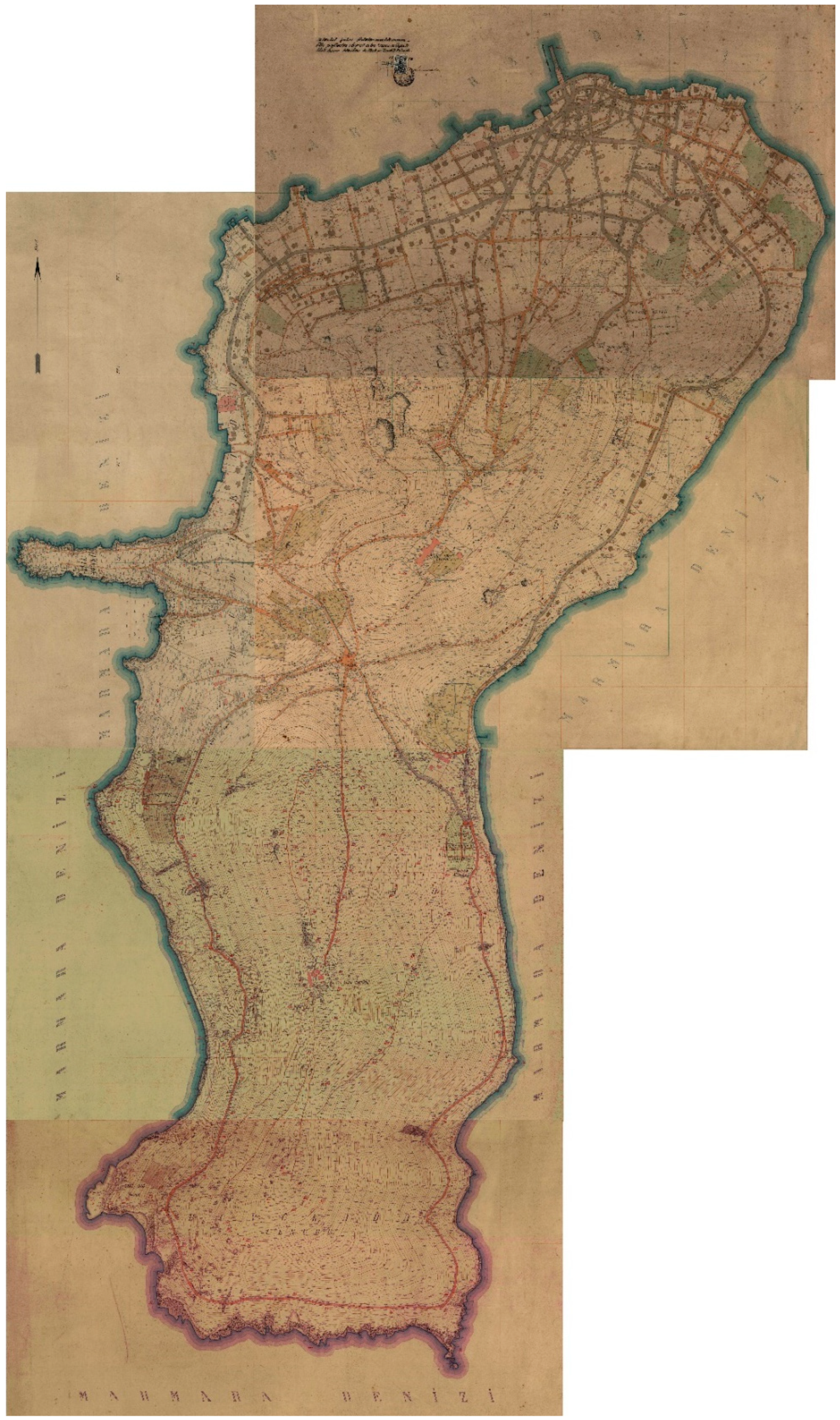

2]). The Princes’ Islands consist of Büyükada (Prinkipo) (

Figure 2), Heybeliada (Halki), Burgaz Adası (Antigoni), Kınalıada (Proti), Sedef Adası (Terebintos), and the four smaller uninhabited islands of Kaşıkadası (Pita), Yassıada (Plati), Sivri Ada (Oxia), and Tavşan Adası (Neandros). All nine islands are located in the northeastern corner of the Marmara Sea.

The Islands are also called “Red Islands” (Janin, 1964 [

3]) because of the rich mineral content in their soil that not only gives it its characteristic reddish hue, but also supports a diverse flora dominated by

Pinus spp. and

Maquis, which are perhaps the most prominent features of the Islands’ silhouette (

Figure 3).

Büyükada, as the largest island of the Archipelago, has hosted successively Armenians, Greeks, and the Turks throughout its history. Gold coins of Philipp II (Bosch, 1951 [

4]) are evidence of inhabitation during classical antiquity in Büyükada. After the Byzantine emperor Justinus II built a palace and monastery (Müller, 1841–1873 [

5]) in this simple fisherman’s village, Büyükada started to gain significance and more churches and monasteries were slowly built over the ancient remains.

Büyükada was established around the historic pier in the Byzantine period, and has expanded continuously since then. During the Byzantine Empire, this isolated piece of land, with fisherman’s huts and monasteries distributed among the fields, was a serene place to refugees, exiles, and monks who lived in or around monasteries and engaged in vini- and horticulture. The fishing village, which was initially built near the seaside, started to grow around the monasteries alongside the agricultural activities. Consequently, until the conquest of Istanbul by Ottoman Turks in 1453, Büyükada witnessed numerous sieges and lootings because it was rich in resources gained from agriculture and fishing (Kritovoulos, 1970 [

6]).

In 1562, during the Ottoman period, Christians fleeing a plague epidemic were sheltered on the island (Mamboury, 1943 [

7]). Evliya Çelebi mentions that, in 1641, Greek fishermen settled on the island (Kurşun, 1996 [

8]) followed by wealthy non-Muslim communities in the 19th century after regular ferry trips were scheduled by Şirket-i Hayriye in 1846 (Çelik, 1996 [

9]). At this time, the edges of the settlement were defined by planting areas, which were located around the borders of the residential areas. As the Adalar cruise was initiated, the settlement expanded out from the pier in an east–west direction.

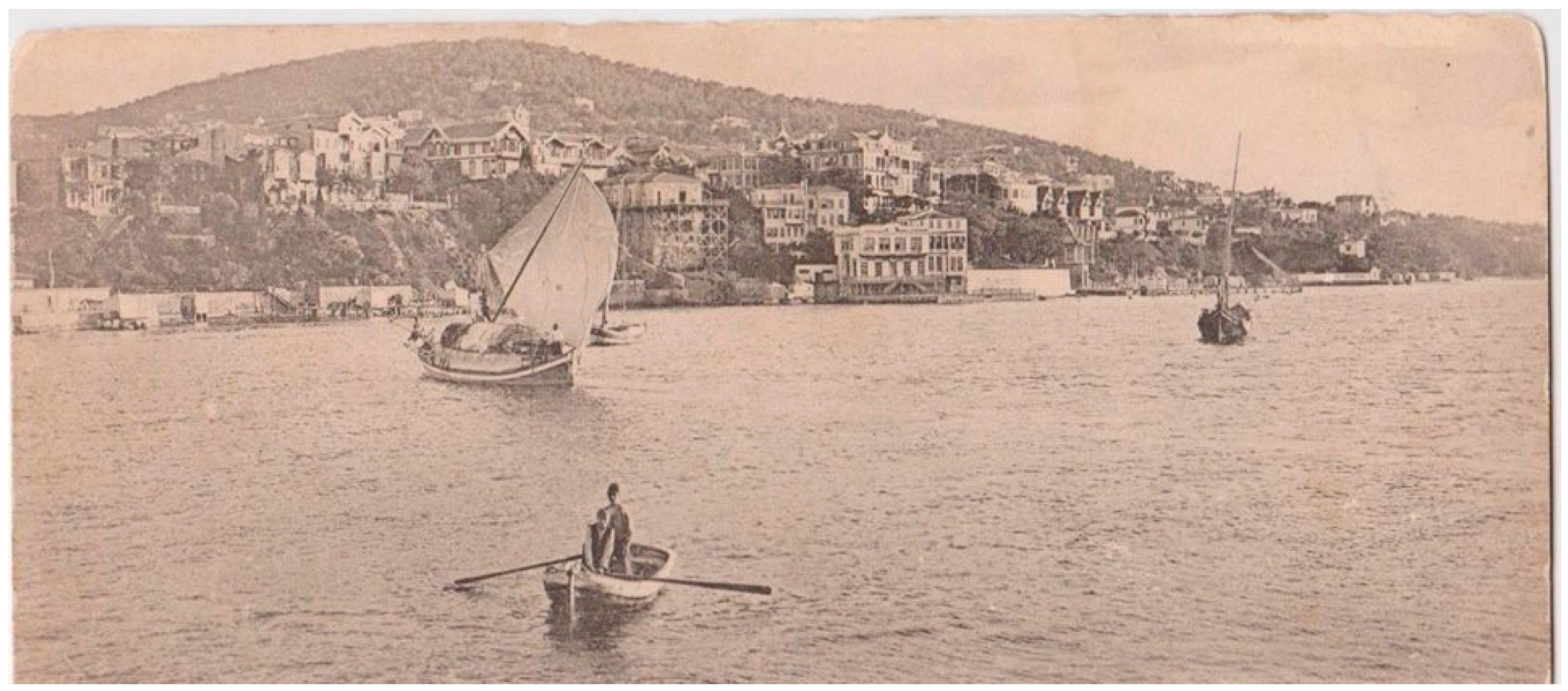

With the establishment of non-Muslim communities, Büyükada gained popularity and Armenians and Greeks began to settle there in large groups as a result of the elite, western, and liberal lifestyle the islands offered. In this era, wooden and masonry mansions aligned along the green hills began to form the architectural values of Büyükada (

Figure 4). Hence, characteristics of the urban fabric, such as Neo-Classic, Neo-Gothic, Neo-Baroque, and Art Nouveau architecture, started to take shape among the organic landscapes. Reinterpretations of Classic, Gothic, Baroque, Art-Nouveau, and Imperial Architecture have flourished in the masonry and wooden civil architecture on the Island, constituting a finely selected building stock as individual examples of different architectural styles. Art-Nouveau elements are particularly common in wooden architecture, and could be easily applied with traditional Ottoman timber construction methods; as a result, “Istanbul Art-Nouveau” (Batur, 2006 [

10]) came into existence. The sustainability of the timber construction method was the reason for the continuity of the typologies and morphologies applied in the vernacular architecture, which also contributed to the preservation of the unique features in the cultural landscape (Barillari, 1996 [

11]).

Because of their isolation, the Islands evolved into a self-sufficient part of the urban system, and the socio-cultural life on the Islands was shaped accordingly. The diversity of the social life also affected the physical environment, forming an architectural style blending the traditional Ottoman style with the eclectic styles of the 19th century. This special environment was designed by well-known architects of the era, such as Fotiadis, Little Nikolaidis, D’Aranco, Vallaury, Kaludis, Poliçis, Azaryan, Dimadis, and the master-builders Dimitri, Dimopulos, Niko, and Simota.

Monumental houses or hotels, such as the Kanzuk Houses by Fotiadis (1898), the Hacopulos Mansion (

Figure 5), the neo-classic Sabuncakis Mansion (1904) (

Figure 6), the Sivastopol Mansion by Dimadis (1885), the Con Paşa Mansion in eclectic style by Poliçis (1880), the Mizzi Mansion in eclectic style by D’arranco, the Kalvokoresis Mansion (

Figure 7), and the Splendid Hotel by Kaludis (1911) (

Figure 8), were all established in grand terraced gardens of diverse exotic flora leading down to the waterfront or street. These delicately designed terraces have service facilities together with semi-open seating areas, such as balconies and verandas, and sometimes have their own docks or piers on the waterfront.

The intention to build a physical and social environment like the ones in Europe resulted in a unique urban fabric and lifestyle associated with phaeton sightseeing, sea bathing ceremonies, moonlight pleasure trips, picnics, musical performances, and sailing competitions as an integral part of daily life.

After the proclamation of the Turkish Republic, President Atatürk converted the former Yacht Club to Anadolu Kulübü in 1926, where he hosted diplomats and bureaucrats as well as members of the Istanbul Bourgeoisie.

Towards the 1940s, new settlements emerged on the south-facing hills. Based on the map by Harita Şirketi, existing urban characteristics of Büyükada, such as building block-plots and street formations, were preserved and have survived intact to date, although, with the newly opened roads and plots of lands, residential areas were expanded into forest areas.

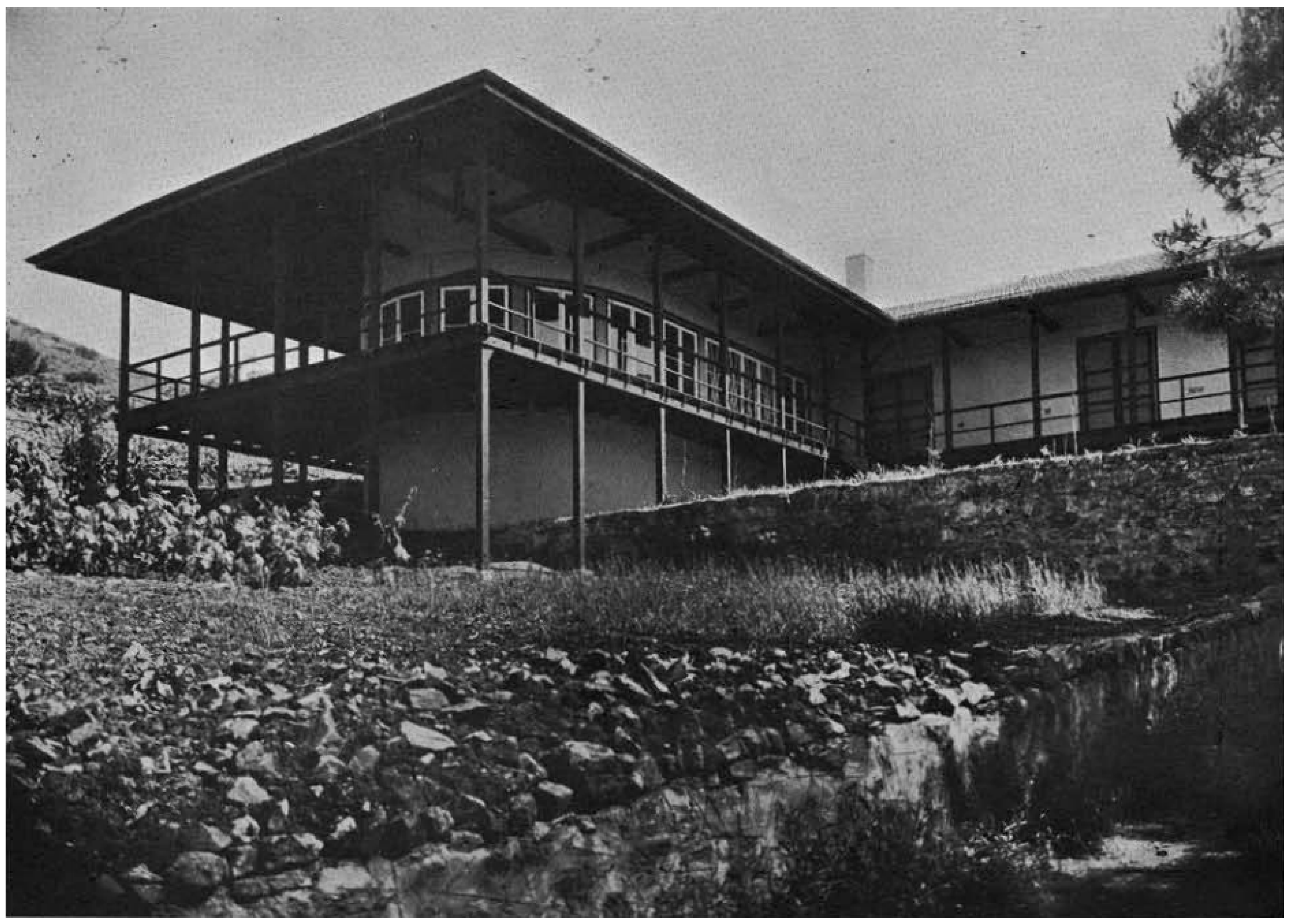

During the Early Republic Period, Art-Deco and Bauhaus influences were quite prominent in the urban fabric, followed by Modernism, which was interpreted freely on large plots, creating an original, experimental architecture in Büyükada, such as the Fethi Okyar House (Önal, 1938 [

12]) (

Figure 9) and the Rıza Derviş House (

Figure 10) designed by the well-known Architect Sedad Hakkı Eldem. The contemporary addition to Anadolu Kulübü (Cansever and Hancı, 1959 [

13]) (

Figure 11), designed by Turgut Cansever and Abdurrahman Hancı, is another important example of modern buildings in the architectural history of Turkey.

Towards the middle of the 20th century, there was a decrease in Büyükada’s population due to migration, initially because of the limited resources and lack of transportation alternatives, and subsequently because of the deportation of non-Muslim communities. In the second half of the 20th century, with the improvement of transportation facilities and infrastructure, the Princes’ Islands became more accessible and attractive as recreational and rehabilitation centers, and Büyükada in particular gained popularity, not only for tourists but also for permanent residents, because of the peaceful environment it offered at some distance from city life.

Büyükada, as a reflection of 19th and 20th century historic urban and natural landscape characteristics, began to lose its cultural and natural assets after its residents abandoned it. Since then, continuing damage has been posing a threat to the natural and cultural heritage on the island. In order to document and maintain the characteristics of the cultural landscape, several studies are being carried out. In recognition of various features unique to the area, which include the vernacular architecture, scenic beauty, magnificent vistas, an organic street pattern without any motorized traffic, and lush greeneries with monumental trees rising in an imposing silhouette, Büyükada was, by decree (dated 10 December 1976 and numbered 9500), registered as a natural heritage site within the Princes’ Islands by the Committee on Conservation of Cultural and Natural Assets. As a result of further inspections that took place in 1984, the Committee, by decree (dated 31 March 1984 and numbered 234), decided to designate all Princes’ Islands as a heritage site, including both cultural and natural sites. Under the same decree, the Committee remarked that Büyükada, Heybeliada, Burgazada, and Kınalıada, which have been inhabited since the 8th century, should be listed as cultural sites due to their religious, military, and civil architecture that is in need of conservation as well as their natural sites due to the picturesque natural character of the hills, ridges, pine woods, lush greeneries, shorelines, bays, and beaches.

It is important to increase awareness about values that accumulate over time. This unique environment, a combination of artificial/fabricated and natural sites, should be nominated as a World Heritage cultural landscape.

2. Materials and Methods: Büyükada as a Cultural Landscape

The definition of ‘Cultural Landscape’ that is acknowledged by the World Heritage Committee (WHC) has been examined in practice for decades, and states that “cultural landscapes are illustrative of the evolution of human society and settlement over time, under the influence of the physical constraints and/or opportunities presented by their natural environment, and of successive social, economic and cultural forces, both external and internal. They should be selected on the basis both of their outstanding universal value and of their representativity in terms of a clearly defined geographical region, and also for their capacity to illustrate the essential and distinct cultural elements of such regions” (WHC, 1997 [

14]).

The category of cultural landscape was initiated by the WHC to implement mechanisms enabling the nomination of sites that could not be managed by existing criteria. A cultural landscape site is more like a distinguishing definition rather than a substitution or an addition to the three existing categories: natural site, cultural site, and mixed site. The guidance prepared by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) clarifies the relationship between natural resource values and cultural landscape values, and describes cultural landscapes as combined works of nature and man. The three categories used by UNESCO for the definition of cultural landscapes are as follows (WHC, 1997 [

14]):

A clearly defined landscape is one designed and created intentionally by man

An organically evolved landscape divided into two sub-categories:

- (a)

a relict (or fossil) landscape

- (b)

a continuing landscape

An associative cultural landscape

In December 1992, the WHC recognized cultural landscapes as a category. To date, 102 properties on the World Heritage List have been designated as cultural landscapes. However, the evaluation of the landscapes required the development of indicators for nomination by International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). In order to be more specific for the nomination of cultural landscapes, an analysis of the first 30 properties of World Heritage Cultural Landscapes has been carried out by experts from ICOMOS and IUCN according to their nature and distribution of common characteristics (in practice and in the rise of certain values). A few characteristics of cultural landscapes are beginning to identify themselves in practice, as indicated by the definitions below (Fowler, 2003 [

15]):

aesthetic quality is significant on the Site √

buildings, often large buildings, are significant √

continuity of lifeway/land use is an important element √

farming/agriculture is/was a major element in the nature of the landscape √

the landscape is, or contains as a major element, ornamental garden(s)/park(s) √

primarily an Industrial Site

the landscape is, or contains elements which are, significant in one or more forms of group identity, such as for a nation, a tribe, or a local community √

a mountain is, or mountains are, an integral part of the landscape

the landscape contains, or is entirely, a National Park or other protected area √

a locally resident population is a significant part of (the management of) the landscape √

survival is significant theme in the landscape, physically as of ancient field systems and archaeological monuments, and/or socially, as of a group of people in a hostile environment

towns and/or villages are within the inscribed landscape √

water is an integral, or at least significant, part of the landscape √

less common characteristics, such as the existence of a jungle/forest/woodland environment, rock art, irrigation or another form of functional water management, lake(s), river(s), and the sea √

Although the list provides some distinctive characteristics in terms of the natural and built environments of the first 30 cultural landscapes, these indicators are more affirmative than definitive. However, according to World Heritage Committee “each cultural property nominated must meet the test of authenticity in design, material, workmanship or setting and in the case of cultural landscapes their distinctive character and components” in order to be nominated as a World Heritage Site.

Although the main trends in selecting cultural landscapes have been identified within the framework provided by the World Heritage Committee in terms of criteria and indicators, there was still a need for ICOMOS to judge a nomination in the field, in desk studies, and in the committee. During the assessment of cultural landscapes, specialists preferred to use more detailed questions to comply with the nomination process. Therefore, more detailed questions (Fowler, 2003 [

15]) were prepared by specialists as a supplement to the WHC criteria and indicators, which we will attempt to answer below in the case of Büyükada, within the extent of our survey and research studies.

2.1. Is the Landscape Significant?

ICOMOS questions whether the landscape has been written about and painted by artists who influenced the course of art and raised human appreciation of the landscape.

The Princes’ Islands, and Büyükada in particular, have been a source of inspiration to many well-known artists and writers because of their picturesque nature, their solitude and serenity, and the rich and colorful lifestyles of their cosmopolitan residents. The remarkable hills and shorelines of Büyükada, such as Değirmen, Aya Nikola, Nizam, Dilburnu, Aya Yorgi, and Yörükali, either formed a background to paintings and engravings (

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) or were featured in stories, poems, and songs that left a mark in memories.

Prominent writers of Turkish literature, such as Nurullah Ataç, Recaizade Mahmut Ekrem, Reşat Nuri Güntekin, Hüseyin Rahmi Gürpınar, and Yahya Kemal, liked to spend time on Büyükada to produce their works by putting their feelings and thoughts on poverty, solitude, adventure, escape, and serenity into words in their books and poems. Most of the time, they socialized on Büyükada and discussed the political issues of their time.

The Russian revolutionary, Marxist theorist, and Soviet politician Leon Trotsky was deported from the Soviet Union in 1929 and took up residence with his wife and son on Büyükada, where he wrote his autobiography,

My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography, while he was in exile (Coşar, 2015 [

16]). Trotsky and his wife lived in the Sivastopol Mansion and the İliasko Mansion on Büyükada until July 1933 and left a mark in the urban memory of the Island.

2.2. Is the Landscape of ‘Universal Significance’?

ICOMOS looks for evidence that the landscape bears upon, tells about, or is witness to great themes common to the world; e.g., the natural/human relationship itself, long-term religiosity, or expression of reverence for a ‘holy’ mountain or river.

The diversity of the religious buildings that still stand in Büyükada on a small piece of land (450 ha) is testimony to the cultural mosaic that has existed there to date. Some of the prominent examples are: Hamidiye Mosque, Panayia Church (Greek Orthodox), Ayios Dimitrios Church (Greek Orthodox), Santa Pacifico Latine Church (Roman Catholic), Surp Asdvadzadzin Church (Armenian Catholic), Aya Nikola Monastery, Hristos Monastery, and Aya Yorgi Monastery, most of which were built on ancient Roman and Byzantine remains.

Currently, Büyükada’s cosmopolitan society consists of Turks, Sunnis, Alevis, Kurds, Laz, Greeks, Armenians, Latins, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Jews, Levantines, Italians, Bulgarians, other Slavic groups, Swedes, Germans, and Austrians living together with their different ethnic roots and worshipping side-by-side (Schild, 1998 [

17]). The tolerance and respect they show each other create a spiritual atmosphere and a unique synergy on the Island.

2.3. Is the Landscape ‘Outstanding’? If So, in What Respect?

ICOMOS evaluates qualities that lift a particular landscape out of the ordinary. It may be outstanding in terms of the engineered reshaping of the landscape and the aesthetic qualities of the outcome. It may be the site of a great event, such as a battle that was a real turning point. It may be a place where outstanding families lived, worked, and created great achievements.

The Islands surrendered to Captain Derya Baltaoğlu Süleyman before the Conquest of Istanbul. During the siege, it was mentioned that there was a fortress where the Turkish flag was raised first. Kritovoulos and S. Runciman (Runciman, 1453 [

18]) wrote about the remains of the fortress that the Council of Monuments registered by decree (dated 13 November 2014 and numbered 2246) as a Grade I Archeological Site.

The outstanding Universal Value of Büyükada is formed through its topography, which is enriched by wooden and masonry architecture and the lush green landscape that composes its distinctive silhouette. Additionally, the western-influenced social environment created a unique lifestyle on the Island that is associated with phaeton sightseeing, sea bathing ceremonies, moonlight pleasure trips, picnics, musical performances, and sailing competitions.

2.4. Alternatively, is the Landscape, Rather than Being Absolutely Outstanding, a Particularly Good Representative of a ‘World-Type’ of Landscape?

ICOMOS values examples of landscapes that are illustrative of a particular theme in a particular region. It greatly appreciates a demonstrable context of land-use type, landscape function, such as transhumance, or landscape design; landscapes that are, in a sense, ‘representative’.

It is known that horti- and viniculture were practiced in the fields of monasteries in the past, providing Büyükada with a strong and independent economy even during World War I. In addition to agricultural activities, the mining of stone, brick, lime, iron, and copper were carried out all around the Island. All of these materials were either used on Büyükada or transported to Istanbul for construction works.

Before the Industrial Revolution, most of the urban travel in Istanbul was on foot; boats and horse carts were used mainly by Ottoman Sultans and rarely by the public until the beginning of the 19th century. In the following years, horse carts were used in Istanbul as a form of public transport until the mid-19th century; however, as technology advanced, they gave way to motorized vehicles. On Büyükada, phaetons have been preserved as a tradition that has provided a mild and fresh climate, which is healthy for patients as well. Additionally, the urban fabric in Büyükada has been shaped according to pedestrian and phaeton movements that blend in with the topography, creating an organic pattern. Transportation in Büyükada has been provided with phaetons for over 150 years, and motorized traffic is still not allowed except for official vehicles, which turns out to be one the representative characteristics of Büyükada.

2.5. What Exactly are the Qualities of Authenticity and Integrity Possessed by a Particular Landscape?

In the case of landscaped parks and gardens, is it the work of one family, one architect, or one landscape designer? If so, where does it stand in their oeuvre?

Well-known and wealthy families of the period built significant houses in beautifully designed gardens with their names and contributed to the architectural heritage of the Island, such as the Zarifi Mansion, the Hacapulos Mansion, the Sabuncakis Mansion, the Kalvokoresis Mansion, the Con Paşa Mansion, the Splendid Hotel, the Agopyan Mansion, the Kastelli Houses, the Mizzi Mansion, the Güntekin Mansion, the Fabiato Mansion, and the Sivastopol/Troçki Mansion. The Greek Orphanage, which was designed and built by Vallaury, has been standing for almost 100 years on the Hristos Hill as a remarkable wooden architectural masterpiece. However, it has unfortunately been neglected for many years, and therefore has been shortlisted for the seven Most Endangered programme 2018 by Europa Nostra (

Figure 15).

2.6. Is There Evidence for a Large, Even Huge, Input of Human Energy and Skill, Perhaps in Moulding an Extensive Area for a Particular Function Such as Worship, Irrigation, Agriculture, Communication, or Artistic Effect? Does the Effect Even Enhance Its Environment and Was the Outcome Significantly Influential Technically or Aesthetically?

Architectural styles that were applied widely in Istanbul during the 20th century have been implemented on Büyükada with wooden interpretations. It has created an architectural language reflecting the elite lifestyle of the society by shaping the urban and cultural mosaic of Büyükada.

2.7. Is There Evidence of Long-Term Management or Stewardship?

Did this nevertheless end in the past or has its effect been towards sustainability until the present?

Büyükada has been administrated under the Islands’ Municipality since the 19th century. The first users of the Island, escaping from the socio-cultural pressure of Istanbul, used and preserved this particular environment with great care, sensibility, consciousness, and awareness until the mid-1920s. From 1930 to 1970, due to the lack of a legislative framework, many random interventions were performed; however, Büyükada remained almost intact until 1973, when the first steps were taken for conservation. In 1973, building registration studies were carried out, and, in 1984, “Transition period construction principles” were initiated in order to fill the gaps in the legislative framework. Currently, the 1/5000 Conservation Plan is in effect; however, the Council of Monuments stopped the execution of the approved 1/1000 Conservation Plan.

Büyükada has gone through a number of changes over the course of time, causing erosion of the urban fabric, a process that accelerated especially after the dispersal of the first users from the island around the 1960s. However, the characteristics of the landscape have been preserved to a large extent until today, and Büyükada still reflects its authenticity. Affirmatively, new planning developments are projected, including individual efforts and local interests, in order to maintain the authenticity and sustainability in Büyükada to alleviate the pressure of its being a satellite of Istanbul.

2.8. Is the Landscape of Great Scientific Value?

ICOMOS assesses whether a nominated landscape possesses outstanding natural resources, such as special floral and faunal communities or scientifically important geological or geomorphological deposits, or contains exploitable minerals. The local community itself may be of considerable anthropological interest, or a landscape may contain an outstanding ensemble of archaeological survivals.

Büyükada is famous for its beautiful shorelines that are enriched by Pinus pinea, Pinus brutia, and Pinus pinaster, thus creating a distinctive silhouette. These shorelines have been used as beaches and have sustained their function until today.

On the island, there are many trees enriching the natural landscape that are listed as monumental and under the preservation of the Council of Monuments. Recreational areas, such as Dilburnu and Büyükada, were registered as Natural Parks in 2011, and contribute to the active green areas of the Island together with the country clubs that are located on the prominent hills.

Mansions with rich landscape arrangements, such as sets and terraces going down to the water front, enriched by water features, pools, and pergolas in between the diverse flora of these gardens exhibit an open “Arboretum” (Yaltırık, 1993 [

19]) on Büyükada. The exotic flora in these gardens present a rich plant composition that varies from cedrus, pinus, and acacia to morus, cercis, and wisteria and adds value to the island’s landscape functionally and aesthetically (Uzun, 1991 [

20]).

Gold coins of Philipp II (Father of Alexander the Great), which were discovered in 1930 and are known as “The Büyükada Treasure”, are the earliest findings relating to the Island’s history. The treasure consists of 207 golden coins, which constitute evidence that Büyükada was inhabited during classical antiquity, that are still being exhibited in the İstanbul Archaeological Museum.

2.9. Is There a Management Plan or Evidence of Long-Term Traditional Management of the Potential Site as a World Heritage Site, Not Just as a National Designation?

Is there evidence of a good, modern understanding of conservation management? Is there partnership with local interests?

Although there is no management plan yet, studies have been carried out by the Municipality together with partnerships and individual study groups in order for the Islands to be nominated for the World Heritage List.

2.10. What Are the Political and Intellectual Contexts of the Nomination? Does the Nomination, for Example, Come From a State Party with Few or Many World Heritage Sites? Is the Nominating State Party One with a Tradition of Academic Landscape Study?

There is no state party executing the nomination process; just the individual efforts of experts, including architects, planners, historians, and economists, gathered together under a non-governmental organization (NGO) called Adalar City Council. Discussions are held regarding the nomination process and issues are put forward.

3. Results and Discussion

We aimed to assess the characteristics of Büyükada in terms of the Cultural Landscape criteria and indicators by supplementing them with the questions prepared by ICOMOS.

Firstly, Büyükada was evaluated according to UNESCO’s Cultural Landscape criteria and proposed for inclusion under “Category 1” as a cultural landscape. It represents a slow-paced, serene, and peaceful islandscape with its natural beauties, organically evolved streets, and aesthetically designed urban fabric and gardens. This natural and historic character has always been identified by social communities, especially by non-Muslim Communities, and their distinctive lifestyle, which gives Büyükada its historic, holy, sacred, and spiritual character and makes it unique and authentic as a cultural landscape.

Secondly, when Büyükada was evaluated according to the distinctive characteristics of the first 30 cultural landscapes, it was found to comply with 11 out of 14 items. Its aesthetic quality is formed by the significant buildings, lush greeneries, and well-designed gardens that shape the picturesque silhouette, which is enriched by the continuing lifestyle of the society as a registered cultural and natural site together with its coastline.

Additionally, the authenticity and integrity of the Island was judged according to existing characteristics of the cultural landscape. The identity of Büyükada has been affected by the lifestyle on the Island as a whole with its natural, social, and physical characteristics for many years. This has caused a unique architectural language to be formed, which blends in with the topography and landscape. The society that lived on the Island during the 19th and 20th centuries has shaped this urban life and fabric, which give the place its spirit and make it authentic, and these characteristics have largely been preserved to date.

Finally, supplementary questions asked by ICOMOS were assessed and validated by the authors in the case of Büyükada. The Island is significant as a landscape in that it has been a source of inspiration to many artists and writers as well as to its community with the serene and spiritual atmosphere it has offered. The landscape is considered to be outstanding in respect of the archaeological evidence for inhabitancy during classical antiquity and the past agricultural and mining activities, which created an independent economy and forced the unique architectural language to be shaped as a reflection of the elite lifestyle and cultural mosaic in Büyükada. Its authenticity lies in the social and architectural environment that was created by well-known architects and has been identified by local communities, which gives the landscape its sense of place associated with phaeton sightseeing, sea bathing ceremonies, moonlight pleasure trips, picnics, musical performances, and sailing competitions as an integral part of daily life.