Unburying Hidden Land and Maritime Cultural Potential of Small Islands in the Mediterranean for Tracking Heritage-Led Local Development Paths

Abstract

:1. Introduction

‘Oceans have more historical artifacts than all museums of the world combined’

- Community engagement for imbuing a UCH narrative with meaning, stories, and identity for communities and/or persons.

- Evolutions in the tourism market, e.g., diving community, signaling a rapidly emerging and distinguishable trend towards underwater cultural tourism [11]; and forcing tourism supply and destinations to explore and deliver new, diversified, and experience-based products that integrate land and underwater CH.

- Comprehension of the role UCH can play towards the sustainable, heritage-led local development [12], especially in less privileged insular communities.

- Significance attached to maritime resources and economy [12], explicitly articulated in the blue growth strategy of the European Union (EU); and motivating interest, among others, in the exploration and sustainable exploitation of UCH.

- Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP) and Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) set up by the EU, which offer a new glance and open up new opportunities for regulating maritime uses [13] and demarcating UCH protected areas.

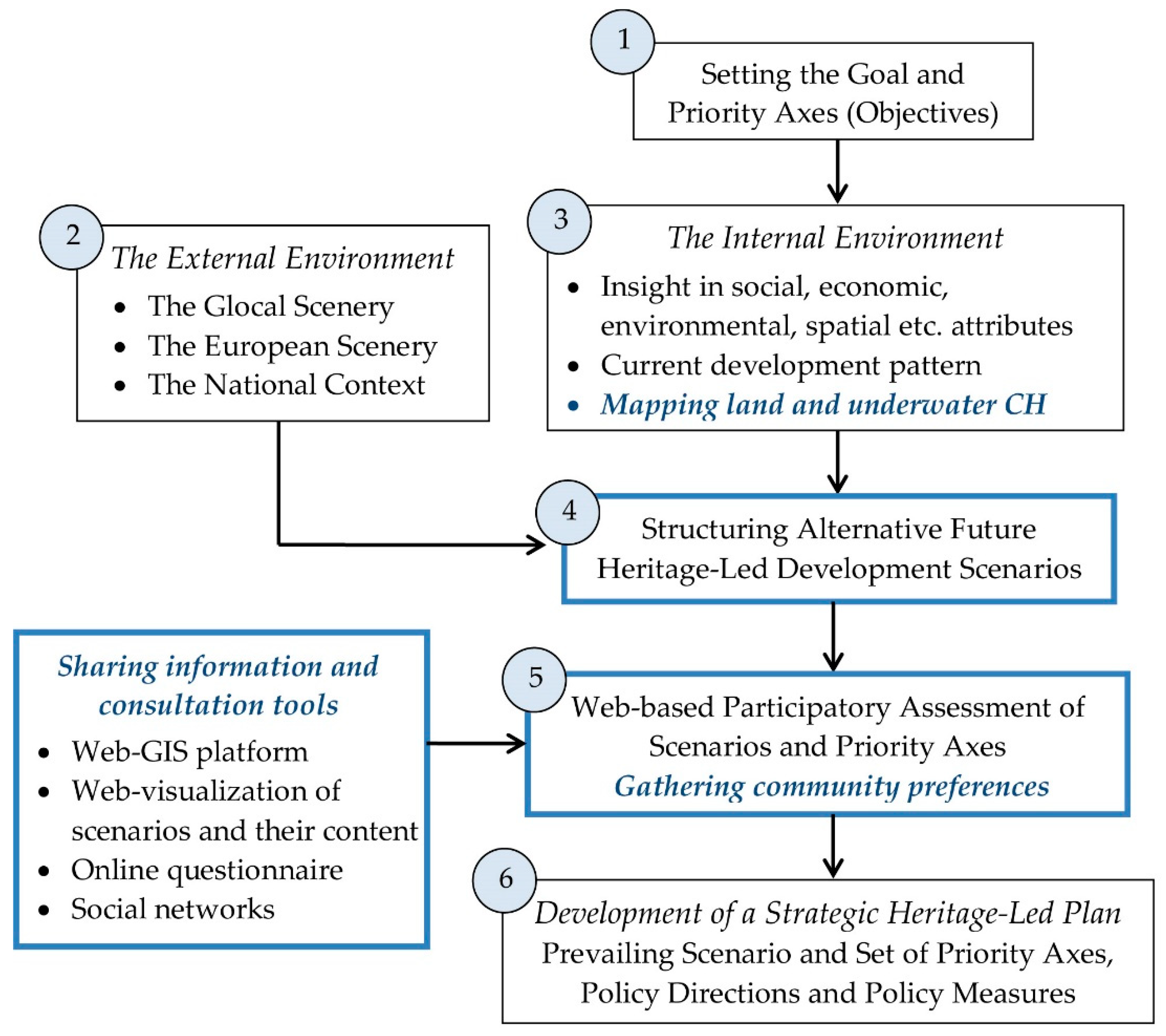

2. The Methodological Approach

- Step 1: Setting the goal and priority axes. The main goal to be achieved is set at this starting point. In the context of this article, this is associated with the sustainable heritage-led development of isolated small- or medium-sized Mediterranean islands through the sketching of spatially defined cultural heritage trails that are largely grounded on the integrated management of tangible and intangible WW II (U)CH. Additionally, a number of priority axes are outlined in this step that correspond to identified key challenges of the particular case study; and trace out key directions of policy action in order for the goal to be achieved.

- Step 2: Exploration of the external decision environment. It attempts to shed light on the current trends and policy arsenal at the global, European, and national level, sketching in particular the decision-making environment and policy directions as to the cultural and tourist sector, the maritime policy, and the protection framework of (U)CH.

- Step 3: Exploration of the internal environment. It incorporates an in-depth spatial analysis and GIS mapping of the area of concern, elaborating on natural and cultural resources, socio-economic status, infrastructure, etc. This analysis supports the full comprehension of peculiarities of the particular socio-economic and cultural environment, which in turn facilitates the structuring of appropriate heritage-led future development paths.

- Step 4: Structuring alternative future heritage-led development scenarios. This step elaborates on the structuring of distinct scenarios that are grounded in the work carried out in Steps 2 and 3. A scenario planning exercise is conducted in this respect, targeting the sustainable exploitation of (U)CH in the study area, with emphasis being given on the spatial pattern of cultural development trails and the handling of land and maritime CH in an integrated manner.

- Step 5: Web-based participatory assessment of scenarios and priority axes. It aims at digitally engaging local community as consultants in this step of the planning exercise so as to evaluate and rate proposed scenarios and related priority axes for their implementation. The step is grounded on mature tools and technologies for information sharing and community engagement, such as Web-GIS platform, Web-GIS visualization of scenarios and their content, Web-based questionnaires, social networks etc. These are used for spreading information with regard to planning choices and engaging local community in their assessment.

- Step 6: Development of a Strategic Heritage-Led Plan. It constitutes the final outcome of the proposed framework that rests upon the most preferred scenario and the prevailing priority axes for its implementation, as perceived by the local community. The latter are further expatiated on policy paths, i.e., policy directions, measures, and actions, best serving the goal set.

3. The External Decision Environment

3.1. The Global Scenery

3.2. The European Scenery

- “European agenda for culture in a globalizing world”—explores the relationship between culture and Europe in such a world in order for the objectives of a new EU Agenda for Culture to be articulated; and new models of cooperation and partnerships to be sketched [36].

- “Agenda for a sustainable and competitive European tourism”—addresses sustainability and competitiveness objectives as decisive drivers for long-term prosperity of the European tourism sector, accomplished by ensuring the right balance among tourists’ welfare, health of the natural and cultural resources, and development and competitiveness of destinations and businesses [37].

- “Europe, the world’s No 1 tourist destination—a new political framework for tourism in Europe”—identifies directions for action that are focusing on the promotion of a sustainable, responsible, competitive, resilient, and high-quality European destinations’ image [38].

- The “European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage”, also known as Valetta or Malta Treaty (1992)—an international legally binding Treaty within Europe, setting the ground for preservation, conservation, and management of land and underwater archaeological heritage as a source of the European collective memory and an instrument for historical and scientific study [39]. Signed on 16 January 1992, it came into force on 25 May 1995. With 45 signatures and 45 ratifications, it is one of the most successful Conventions of the Council of Europe.

- The “European Landscape Convention”—also known also as the Florence Convention, it is the first International Treaty that is exclusively addressing all aspects of European landscape [40]. It aims at the protection, management, and planning of these landscapes, by establishing suitable cooperation on relevant issues. Today, 39 member states have ratified this convention (Status as of 15/02/2019), [41].

- The “Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society”—known also as the Faro Convention [42], it attempts to delineate issues at stake, general objectives, and possible fields of intervention with respect to CH. It stresses the importance of individual and collective responsibility with regard to CH management and enrichment aspects; while it also emphasizes the mediating role of CH in building up peaceful and democratic societies. Adopted in 2005, it came into force on June 1, 2011. To date, 17 member States of the Council of Europe have ratified this Convention and 5 have signed it.

3.3. The National Context

- The Law 3028/2002 [50] “For the Protection of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in general” integrating into one law all partial legislative actions holding through time; and addressing the protection of (U)CH. With respect to UCH, Articles 1 and 2 of this Law refer to the ancient archaeological sites, located at the seabed or the bottom of lakes or rivers [49]. The same articles state that “cultural objects within the boundaries of the Greek territory, including territorial waters, as well as in other maritime areas, where Greece has jurisdiction under the international law of sea” are subject to legislative protection [51]. Furthermore, in accordance with Articles 2d and 16, protected historical marine sites may be declared as areas where historical naval battles took place; while in Article 20 (paras. 1d and 6), it is stated that contemporary newer shipwrecks may also be considered as monuments.

- A Ministerial Decision of 2003, according to which shipwrecks are recognized as cultural goods and as monuments, in case they lie in the Greek seas for more than 50 years. This further enhances protection of shipwrecks as UCH, in contrast to the UNESCO Convention, which declares shipwrecks as monuments when they lie underwater for more than 100 years.

- The Law 3409/2005 [52] predicting the establishment of diving parks for recreational diving, diving training, scientific research, etc. This has resulted in the disengagement of diving throughout the Greek coastline, as opposed to the previous regime, where diving was permitted for 620 out of the 10,000 miles of this coastline [53].

- The Law 4179/2013 [54] establishing access to Maritime Archaeological Sites. According to this Law (Article 44), it is possible to make cultural development contracts, specifying cultural projects, programs, and related services within Maritime Archaeological Sites.

4. The Internal Environment—Leros Island/Greece

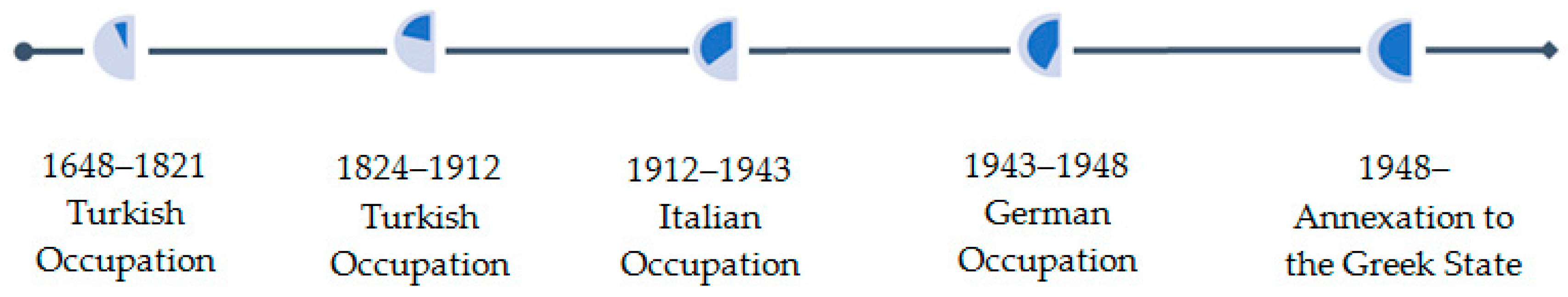

4.1. The Study Region

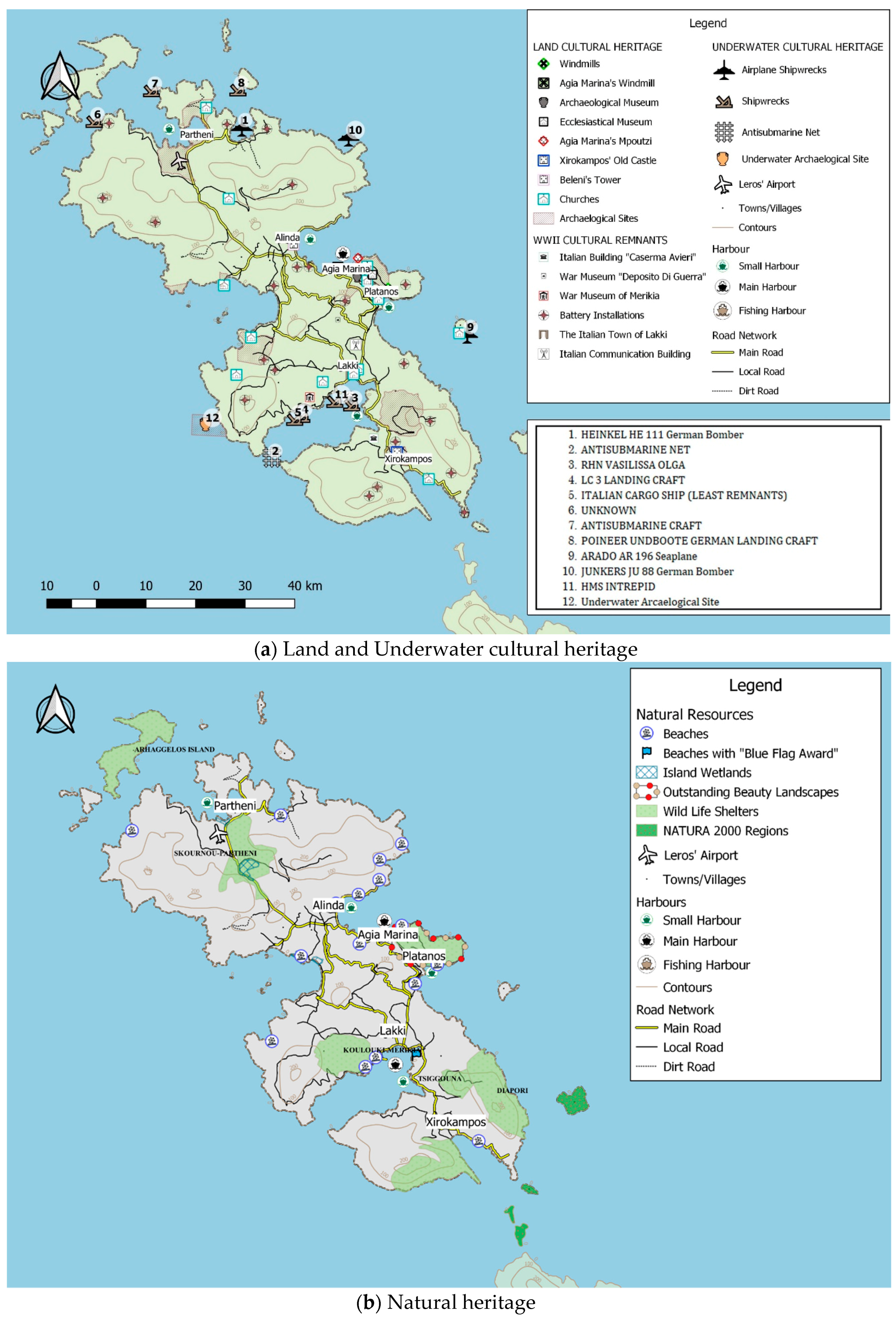

4.2. Mapping Cultural and Natural Resources of Leros Island

5. Structuring and Participatory Assessment of Future Development Scenarios for Leros Island

5.1. Goal and Priority Axes of the Leros Planning Exercise

- Designation of the local cultural identity as a pillar for economic development and social cohesion—refers to the strengthening of local identity and its power for serving local development purposes through mapping natural resources as well as (U)CH; and realizing their very essence, value, and spatial distribution.

- Treatment of (U)CH in an integrated way—a vital objective for the case study concerned, as considerable parts of both the land and underwater—tangible and intangible—CH have a common origin, i.e., WW II fatal events, and thus are parts of the same narrative.

- Integrated approach of natural and cultural resources—as both types of resources co-exist in many parts of the study region, an integrated approach in their handling is perceived as further enriching the value and experience gained out of them.

- Development of alternative, experience-based, cultural tourism products—in alignment with the globally noticeable trends as well as the European, national, and regional policy priorities, cultural tourism, pursued by this priority axis, is perceived as a remarkable developmental pillar in insular regions, being important repositories of natural and cultural resources.

- ICT-enabled promotion of land and underwater cultural heritage—use of technological advances is a key factor for dealing with restrictions faced by geographically isolated areas, such as the small- and medium-sized Mediterranean islands; and an indispensable means for effectively marketing local cultural tourism products in a globalized era.

- Enhancement of local entrepreneurship and creation of value chains—it aims at enabling networks’ creation and clustering of local businesses for strengthening value chains’ creation and boosting extroversion of local products and services.

- Raising awareness of local community on the value of natural and cultural resources—an essential priority axis, targeting the realization of value of local natural and cultural resources, their decisive contribution to local development, and the need for their preservation and sustainable exploitation.

- Balanced cultural tourism development—removal of inequalities: It attempts to reverse the current spatial pattern of mass tourism development, which depicts a certain concentration in the central-eastern part of Leros Island, in contrast to the more evenly dispersed natural and cultural resources.

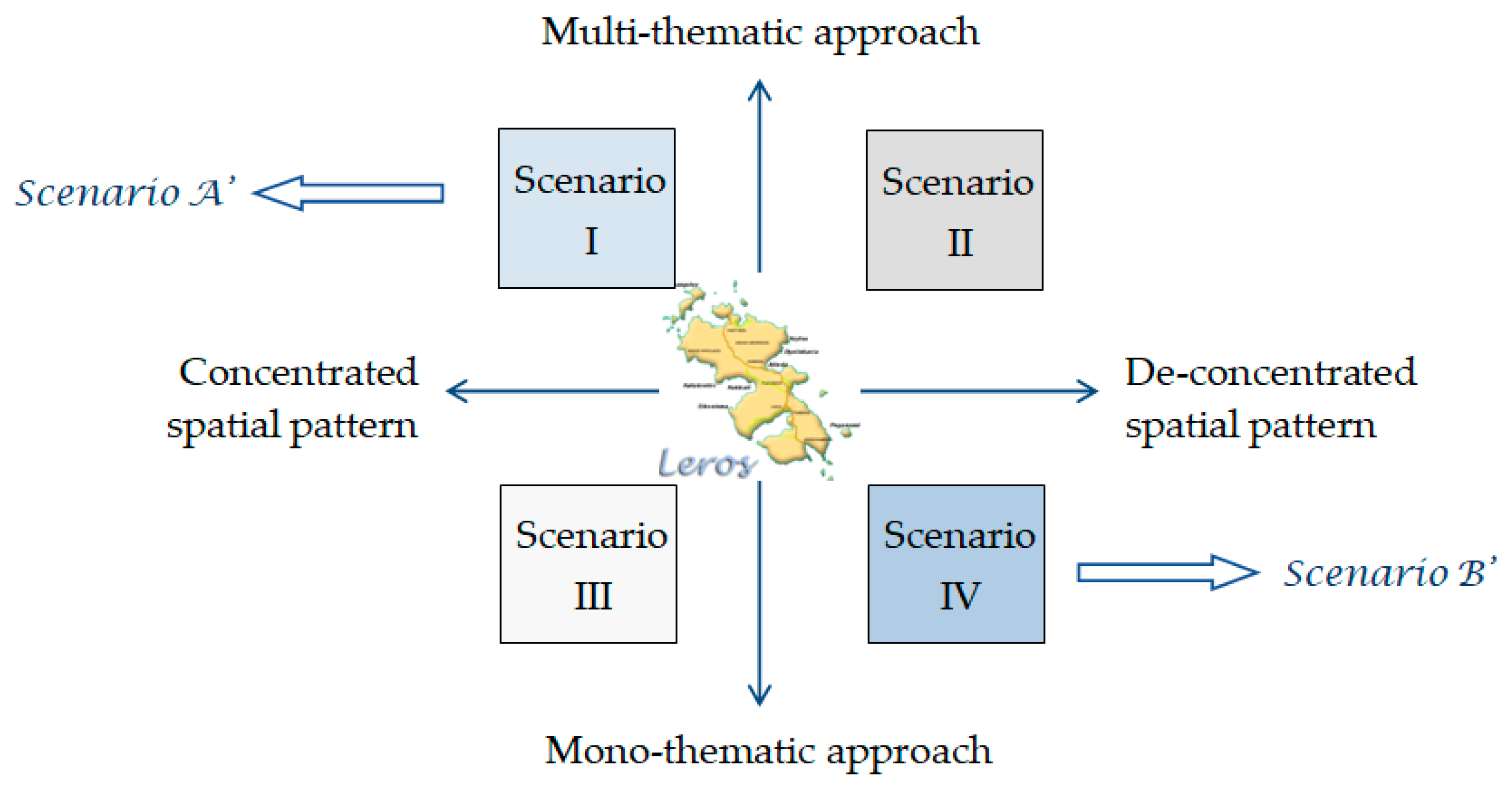

5.2. Setting the Scenario Building Rationale

- Leros is a small isolated island of Dodecanese, in the neighborhood of Greek islands that are global, mostly mass, well-established tourist destinations. In order to be able to compete, but also act in a complementary way to the rest of Dodecanese Island destinations, a diversified and challenging narrative should be in place. This should, furthermore, act in a beneficial way for the island as a whole, i.e., serve equity aspects too.

- Tangible and intangible land and maritime cultural resources of the island are strongly associated with the Italian possession and especially with the WW II events.

- Tangible cultural resources are rather evenly dispersed in the study region, both in the land and maritime part.

- In the global tourism market, there is a growing interest in experience-based cultural tourism products in general and UCH activities in particular (e.g., an exponential rise of certified diving community); and a large number of tourist destinations that are placing efforts in building up such products and marketing themselves as qualitative, culturally-driven, worth-visiting places.

- Competitiveness of tourist destinations is, among others, grounded on the variety but also quality and authenticity of cultural tourism products these offer.

- There is a need to further elaborate on a small number of challenging narratives (scenarios) and related policy directions to effectively communicate them to the local community and gather information on their preferences as to the most prevailing one. In this respect, two contrasting scenarios were perceived as a reasonable choice and easy to handle by Leros local community.

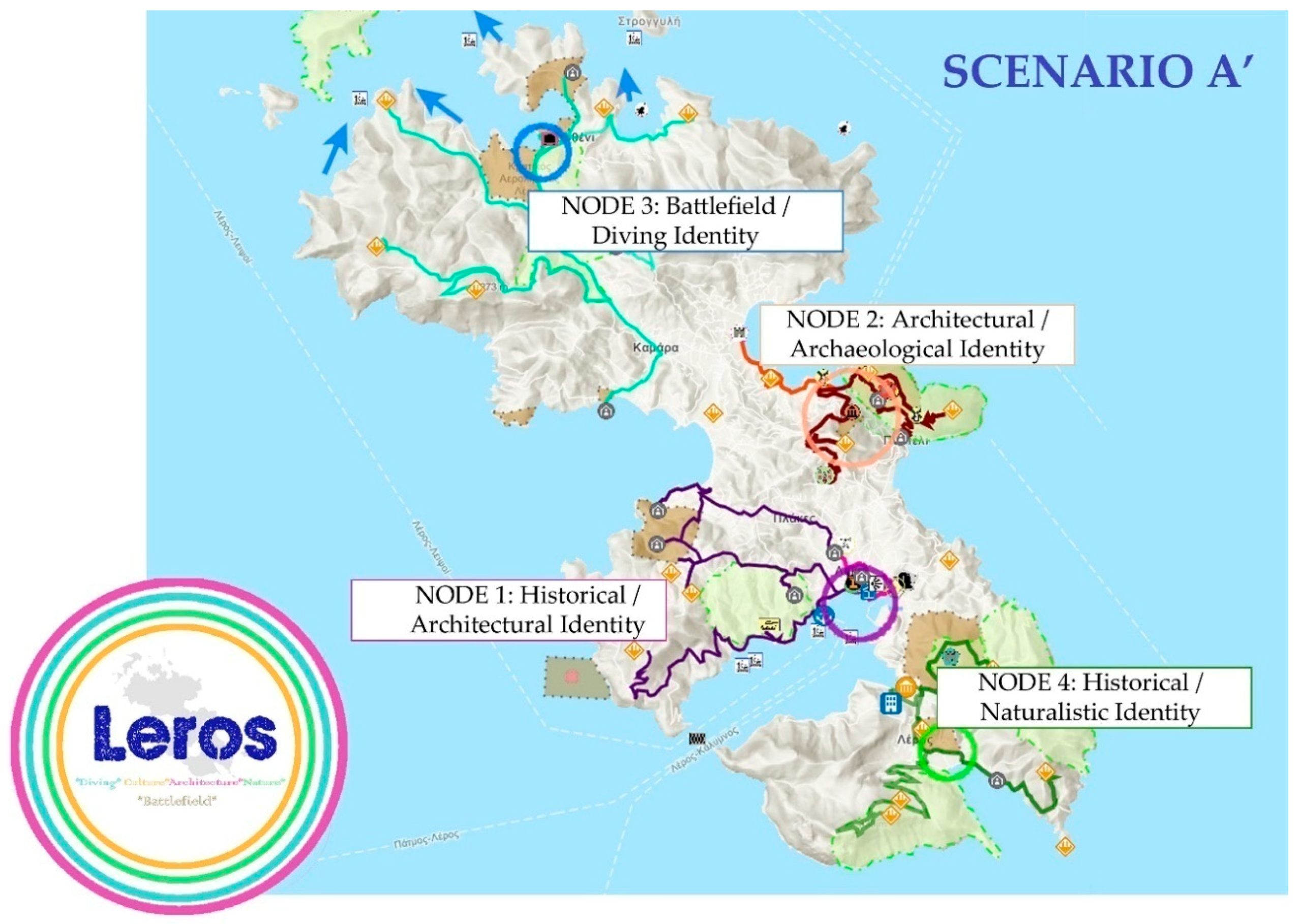

- Node 1: Located in the Lakki settlement, it holds a historical/architectural identity. This is largely conditioned by the Lakki settlement and the large number of buildings with an exceptional architectural design, but also a number of fortification installations and churches, museums, etc., lying in the land part. In the maritime part, a number of globally well-known ship wrecks are also located, most of which were sunk on 26 September 1943, during the fierce bombing of the area from the Germans. UCH is complemented by a buoy and a defense net, both remains of WW II military activities.

- Node 2: It is deployed in Saint Marina settlement (current capital of the island) and its surroundings; and holds an architectural/archaeological identity. The whole area is characterized by landscape of outstanding beauty due to the combined archaeological, architectural, religious, naturalistic, and social interest it disposes. The traditional settlement of Platanos, the very important archaeological site ‘Castle of Virgin’ and a number of churches inherent in it, the Belenis Tower Museum, the War Museum ‘Deposito Di Guerra’, traditional windmills, WW II gun emplacement sites, and the Patella Telecommunication Center, feature the very specific identity of this node.

- Node 3: Expanding in the northern part of Leros Island, in the surrounding area of Partheni settlement, it holds a battlefield/diving identity. The area is closely related to the Italian occupation and WW II, constitutes an important scene of the Leros Battle, and is full of battery sites in the land as well as ship and plane wrecks in the marine part.

- Node 4: Located in the southern part of Leros Island, it expands in the neighborhood of Xirokampos settlement and holds an historical/naturalistic identity. The historical identity is associated with the location of a large number of batteries and the aeronautical base ‘Gianni Rosseti’, all playing an important role in WW II military operations. The naturalistic identity is due to the extraordinary landscape and two areas of outstanding beauty falling in the surroundings of this node.

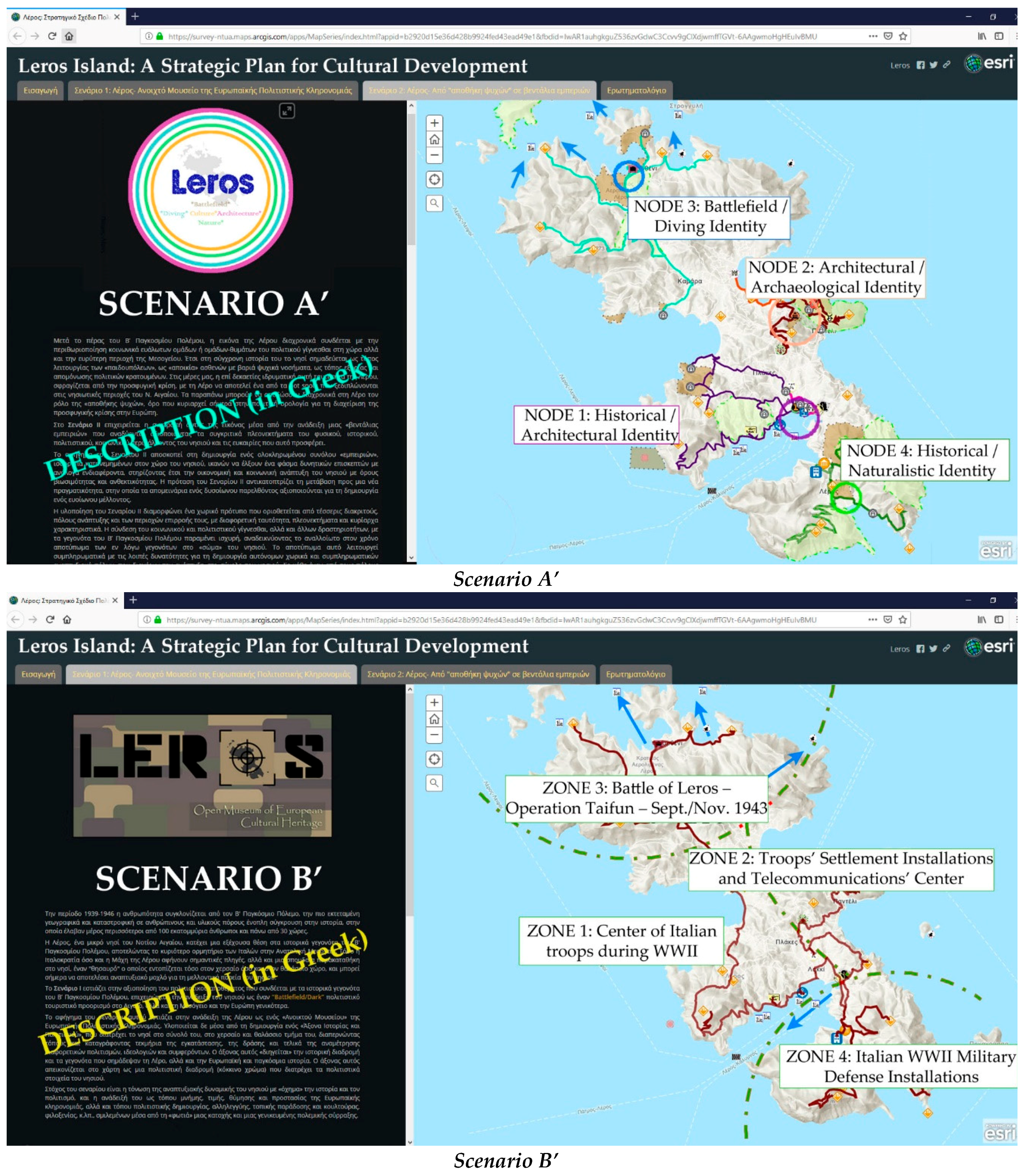

- Zone 1: Operational and social center and main place of residence of Italian officers during the WW II. It incorporates the settlement of Lakki, a port town and a distinguishable architectural entity, and the wider area at the north-western part of Leros Island. The place was sealed by the Italian possession in the sense of buildings’ architecture, spatial organization, etc. Many important remains, such as the Building of Italian Nautical Administration, constitute important landmarks of contemporary times of the island. Moreover, the Military Museum of Merikias settlement falls into this zone, being the only restored tunnel from the very many that are tracked down in the island. In this museum, findings exhibited relate to the Battle of Leros, discovered either in land or marine parts of the island. Finally, in the Lakki bay ‘rest in peace’ in the bottom of the sea the “Queen Olga” and the British frigate “Intrepid HMS D10”, opening up the land cultural tour of Zone 1 to the surrounding marine environment.

- Zone 2: This extends to the central-eastern part of Leros, where lies the capital and the main port of the island today, Saint Marina. A number of past fortification installations can be encountered in this area, coupled with troops’ settlements and the exceptional Patella Telecommunication Center, serving communication needs of Italian troops. Additionally, two very important museums with private collections of findings from either land or the maritime area of Leros are located in this zone, namely the “Depisito Di Guerra” and the Belenis Tower.

- Zone 3: Constitutes the heart of the Leros Battle (26 September 26–16 November 1943) and the Leopard Operation, one of the most important WW II events in Eastern Mediterranean, ending up with the occupation of Leros Island by the Germans (1943–1948). Important remains of this dramatic instance of the European history are a number of battery installations in the land part as well as important remains (ship and plane wrecks) sunk in the surrounding marine area.

- Zone 4: Hosts the industrial zone of the occupying period, the catholic cemetery, the important aeronautical Italian base ‘Gianni Rosseti’ that has played an important role in WW II, as well as important battery installations of the Italian occupancy.

5.3. Participatory Assessment of Alternative Scenarios—Digitally-Enabled Engagement of Leros Community

- In a scale ranging from 1 (completely unexploited) to 5 (fully exploited), 22%, 38%, and 32% of respondents’ replies fall into rates 1, 2, and 3, respectively, i.e., a large share of respondents’ views perceived (U)CH as largely underexploited.

- Respondents realize the uniqueness of Leros Island in terms of its WW II CH and especially UCH and the role these can play for serving sustainable development objectives of the area.

- The majority of them seem to converge on the necessity to adopt a more systematic and integrated cultural planning and (U)CH management approach for serving long-term prosperity of the area in a sustainable and resilient way.

- In planning a sustainable cultural tourism future development of Leros Island, highest priority was given to three priority axes, namely “designation of local cultural identity as a pillar for economic development and social cohesion”, “development of alternative, experience-based, cultural tourism products”, and “balanced cultural tourism development—removal of inequalities”(Table 1). This choice reflects the willingness of local community to keep a distance from current massive and commercialized pattern of cultural resources’ exploitation, as a means for preserving (U)CH, respecting the island’s carrying capacity, ensuring benefits for all, and following future development pathways that are keeping intact local identity, social values, and traditions of the study area.

- Towards such a development, respondents appraise the narrative presented by Scenario B’—a narrative of local but also European and global reach—as more relevant (Table 1), revealing the value attached by the local community to WW II events and their remnants, sealing the ‘body’ (land and maritime), the history, and the people of Leros in the past and present, and eventually in the future, in case this plan is successfully implemented. Scenario B’, according to the local community’s view, seems to be a more promising option towards a sustainable, resilient, spatially balanced, qualitative, and longer-term future. Τhis, among other things, can sustain a unique identity and a competitive advantage of this small island in the Aegean Sea, in alignment with globally evolving cultural tourism trends and demands (dark/battlefield and/or diving tourism or cultural tourism in general).

- Finally, of great importance, although small in number (nine replies), are replies of people in the open question requesting suggestions about how to improve the designed narratives. All were very enthusiastic and reacted positively to this research, adding value by means of additional cultural content; provision of sources of historical information that highlight the significance of Leros events; articulation of remarks on the existence of a multitude of unexploited cultural elements, scattered around the island; narration of personal stories of respondents; provision of suggestions as to how to promote the island’s cultural heritage; etc. Reactions in this part of the questionnaire reveal the passion of people for their history, identity, and values; and their concern for keeping them alive for the future generations.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

- Apart from the highly appreciated land CH in the Mediterranean region, there is a great interest in UCH research. This reflects the abundance of sunk remnants in this area (e.g., ancient cities and harbors, archaeological sites, ship or plane wrecks), which is due to its protagonist role through centuries as a crossroad of various civilizations and a main scene of commercial sea traffic and cultural exchange from ancient years, but also as a ‘Mediterranean Theater’ in WW I and II operations. It is worth noting in this respect that from the 62 state parties included in the UNESCO Convention on the protection of UCH, 13 of them lie on the border of the Mediterranean Sea [85], partly justifying the spatial focus of the present article on Leros Island.

- UCH per se attracts the interest of a variety of disciplines, being a highly interdisciplinary theme. However, research endeavors and empirical evidence on the topic do not, so far, reflect such interdisciplinary approaches, in order the various perceptions to be properly accommodated.

- UCH also attracts the interest of a range of sectoral stakeholders, activating in the coastal and marine space; and having a stake with regards to any decision as to the way this cultural heritage is handled. This raises the necessity for effectively engaging them in relevant decision-making processes.

- UCH protection and preservation is a highly complex planning issue, a “wicked problem” [86], in the sense that it needs to balance technical (e.g., archaeological and heritage management practices), environmental (UCH as sources of pollution or beneficial artificial reefs), social and ethical (human remains), technological (progress in technologies addressing UCH research), but also jurisdictional aspects (national and international laws and Conventions); and adjust actions undertaken to a continuously changing environment—the marine one—affected by global challenges, such as climate change.

- Community outreach and involvement are also issues of critical significance for UCH protection and preservation [87], taking into account that UCH builds in social, ethical, environmental, economical, and historical etc., values of local communities. Any planning endeavor of CH in general and UCH in particular has to respect the self-evident right of local societies concerned to become parts of relevant decision-making processes and respective policy choices. Such a community engagement approach can also act as a learning platform for increasing awareness and cultivating responsibility of all those concerned, by engaging them in the process of co-defining the way this UCH will be managed for paving future sustainable, culturally-driven, and inspiring development trails that embed expectations, indigenous knowledge, and visions [88]. Furthermore, for an effective preservation and protection to be achieved, the role of community volunteerism is essential as a means for spreading interest in UCH and inspiring a sense of ownership, but also contributing to active engagement in research on the topic as well as identification, monitoring, and promoting of UCH sites.

- A first challenge or gap that needs to be properly addressed is the adoption of an integrated planning approach, setting up a shared view of land and marine parts of a region in general and (U)CH in particular. It has to be understood that both constitute parts of one system and one legacy, with (U)CH and other resources having a complementary role in building up a diversified local development perspective. This is crucial for harmonizing relevant (spatial) policies, and broadening their impact to the benefit of both the maritime and the land part and related stakeholders’ groups. Various structured planning approaches and tools can be adopted in this respect (see reference [44]).

- A major challenge in the sustainable management of (U)CH relies on the establishment of substantial communication and interaction among the multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary qualities and expertise required for accomplishing such a task. Indeed, a variety of different perspectives and relative scientific backgrounds need to be incorporated in such an effort (legal, cultural, environmental, social / ethical, economic, spatial, technological), rendering this a cooperative endeavor. As this is not usually the case in practice, it constitutes a considerable barrier in order for the different perspectives and respective technical knowledge to be fully integrated in each specific case study context. This is further hampered by the reluctance of specific research groups (e.g., marine archaeologists or biologists) to open up (U)CH aspects to the research and stakeholders’ communities, leading to a knowledge gap with respect to (U)CH information (location, attributes/documentation, constraints, etc.,) that affects options available and quality of planning outcomes.

- The prevailing, so far, model of hiding (U)CH from public view, although properly justified by relevant researchers, has deprived the diffusion of information to local communities on the value of this heritage, its role for serving local development objectives, and the need to handle it in a responsible, sustainable, and resilient way that safeguards historical memory and evidence and ensures its transmission to future generations. That given, it also impedes motivation for the collection of important evidence, stories, and personal experiences with respect to this heritage (e.g., eye-witnessed WW II incidents in the island of Leros). This fact, apart from depriving the whole planning exercise and narrative emerging out of it, it also threatens to loss this evidence, since people owning this information are quite old. It is, thus, of crucial importance the cultivation of an open and fertile ground for creating win–win end states for both the research and the local community. The Leros exercise has revealed the eagerness of people to engage, share information, and become part of this systematic and integrated planning effort for bettering future perspectives of their land.

- Managing (U)CH in an integrated way implies the need to accommodate the diversified stakes of local community. Indeed, coastal/maritime stakeholders and community actors do not share the same values and do not dispose similar perceptions with regard to local (U)CH and their exploitation. Actually, in certain cases, the two groups can represent rather conflicting stakes. Bridging these differences and establishing a fruitful and creative dialogue among completely different groups (in terms of knowledge and objectives but also power to influence policy decisions), seems to be a real planning challenge and a considerable barrier to overcome. Wisely structuring the participatory planning process and selecting the most appropriate participation tools can provide ways out of these difficulties. Both of these require knowledge that should not be taken for granted in the planning community, while they are essential for collaboratively accomplishing a (U)CH planning exercise. Of importance in this respect is MSP as a means for compromising conflicting to UCH maritime uses, crucial for its protection and preservation. This, as a rather recently policy direction, has not, so far, progressed with a decisive pace, at least as far as arrangements of maritime uses at the local level, like Leros Island, are concerned.

- The use of the Leros Web-GIS application, perceived as a suitable environment for establishing digitally-enabled interaction of local community with the research team of this work, seems, in hindsight, not to be the wisest choice in the specific case study context. This is mostly justified by the skill profile of the local population and the lack of previous engagement experiences. Face-to-face participation tools or a combination of both ICT- and non ICT-enabled (face-to-face) tools would be a more relevant tools’ mix for community engagement, a fact that is also justified by other empirical results in similar types of regions [89]. However, this application is positively evaluated in terms of its communicative power and potential to present the proposed planning choices in a map form, which is more graspable and clearer to those navigating in this environment. Additionally, it incorporates low-cost and mature technologies, meaning that it can be easily replicable to other examples.

- Finally, one crucial issue for effectively implementing planning exercises like the one of Leros is availability of reliable spatial data of mainly maritime origin. Indeed, while gathering of terrestrial data is a rather trivial task, since, traditionally, a variety of data sets are collected from various organizations, the situation is quite different in the case of maritime data. These appear to be scarcer, scattered to various institutions and researchers, and are not always freely accessible or relevant to the study purpose. Both aspects, i.e., availability and quality of data, but also their accessibility, can largely affect the smooth handling of the planning process and the validity of the results obtained; while can also deprive planners from grasping the very details of the marine environment and define, in a transparent way, uses in it that are in favor of UCH protection.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Snyder, Κ. Saving the Oceans, One Person at a Time, Clipperton Project 2017. Available online: http://www.clippertonproject.com/oceans-have-more-historical-artifacts-than-all-museums-combined/ (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- Firth, A. Marine Spatial Planning and the Historic Environment. Unpublished Report for English Heritage. Project Number 5460, Fjordr Ref: 16030. Tisbury: Fjordr Limited. 2013. Available online: http://www.fjordr.com/downloads.html (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Forrest, C. Defining Underwater Cultural Heritage. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 2002, 31, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, W.B. Understanding and Managing Marine Protected Areas through Integrating Ecosystem-based Management within Maritime Cultural Landscapes: Moving from Theory to Practice. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 84, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Integrated Maritime Policy and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 3rd National Conference of Urban and Regional Planning and Regional Development, Volos, Greece, 24–27 September 2018. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, F.; Lagudi, A.; Barbieri, L.; Muzzupappa, M.; Mangeruga, M.; Pupo, F.; Cozza, M.; Cozza, A.; Ritacco, G.; Peluso, R.; et al. Virtual Diving in the Underwater Archaeological Site of CalaMinnola. In International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Proceedings of the 3D ARCH Conference, Nafplio, Greece, 1–3 March 2017; ISPRS Publications: Hanover, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, G. Threats to Underwater Cultural heritage—The Problems of Unprotected Archaeological and Historic sites, Wrecks and Objects Found at the Sea. Mar. Policy 1996, 20, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder-Myers, L.A. Cultural Heritage at Risk in the Twenty-first Century: A Vulnerability Assessment of Coastal Archaeological Sites in the United States. J. Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 2015, 10, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, A.; Kontogianni, G.; Koutsaftis, C.; Skamantzari, M. Serious Games at the Service of Cultural Heritage and Tourism. In Tourism, Culture and Heritage in a Smart Economy, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference IACuDiT, Athens, Greece, 19–21 May 2016; Katsoni, V., Upadhya, A., Stratigea, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-3-319-47731-2. [Google Scholar]

- Skarlatos, D. Smartening up Engagement in Underwater Cultural Heritage: Key Enabling Tools and Technologies. In Proceedings of the 3rd Euro-Mediterranean Conference on “Featuring Territorial Intelligence of Small and Medium-sized Cities and Insular Communities in the Mediterranean Scenery—Building Bridges between Local Endeavours and Global Developments”, Larnaca, Cyprus, 5–6 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Tourism and Culture Synergies; UNWTO Publications: Madrid, Spain, 2018; ISBN 978-92-844-1896-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kronfeld-Goharani, U. Maritime Economy: Insights on Corporate Visions and Strategies towards Sustainability. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 165, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, M. Aspects of Spatial Planning and Governance in Marine Environments. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, Global Network on Environmental Science and Technology, Rhodes, Greece, 31 August–2 September 2017; ISBN 978-960-7475-53-4. [Google Scholar]

- Stratigea, A.; Leka, A.; Nicolaides, C. Small and Medium-sized Cities and Island Communities in the Mediterranean: Coping with Sustainability Challenges in the Smart City Context. In Smart Cities in the Mediterranean—Coping with Sustainability Objectives in Small and Medium-Sized Cities and Island Communities; Stratigea, A., Kyriakides, E., Nicolaides, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 3–29. ISBN 987-3-319-54557-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Gil, P.R.; Hoffmann, M.; Pilgrim, J.; Brooks, T.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Lamoreux, J.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B. Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions; Conservation International: Arlington, VA, USA, 2005; ISBN 9686397779. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakopoulos, C.; Bindi, M.; Moriondo, M.; Lesager, P.; Tin, T. Climate Change Impacts in the Mediterranean Resulting from a 2 °C Global Temperature Rise. Glob. Planet Chang. 2009, 68, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA—European Environment Agency. The European Environment—State and Outlook 2015; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Taberner, J.G.; Manera, C. The recent evolution and impact of tourism in the Mediterranean: The case of island regions 1990–2002. Working Paper No. 108.06 “Note di Lavoro” Series for FEEM-Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei. Available online: https://www.feem.it/en/publications/feem-working-papers-note-di-lavoro-series/the-recent-evolution-and-impact-of-tourism-in-the-mediterranean-the-case-of-island-regions-1990-2002/ (accessed on 22 November 2016).

- Smith, H.; Maes, F.; Stojanovic, T.; Ballinger, R. The Integration of Land and Marine Spatial Planning. J. Coast. Conserv. Plan. 2011, 15, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasubramanian, L.; Albrecht, J. Essential Methods for Planning and Practitioners—Skills and Techniques for Data Analysis, Visualization and Communication; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-68040-8. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Tourism Trends: The Convergence of Culture and Tourism; Working Paper, Academy for Leisur; NHTV University of Applied Sciences: Brenda, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.; Nam, T.J.; Shi, C.K. Designing an immersive tour experience system for cultural tour sites. In CHI ‘06 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 22–27 April 2006; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1193–1198. ISBN 1-59593-372-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L.; Edwards, D.; Mistilis, N.; Roman, C.; Scott, N.; Cooper, C. Megatrends Underpinning Tourism to 2020—Analysis of Key Drivers for Change; CRC for Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd.: Queensland, Australia, 2008; ISBN 9781920965525. [Google Scholar]

- Stratigea, A.; Hatzichristos, T. Experiential marketing and local tourist development: A policy perspective. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2011, 2, 274–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A.; Katsoni, V. A Strategic Policy Scenario Analysis Framework for the Sustainable Tourist Development of Peripheral Small Island Areas—The Case of Lefkada-Greece Island. Eur. J. Future Res. 2015, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoni, V.; Upadhya, A.; Stratigea, A. Tourism, Culture and Heritage in a Smart Economy, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference IACuDiT, Athens, 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-47731-2. [Google Scholar]

- UNTWO. Tourism Market Trends 2002: World Overview and Tourism Topics; UNWTO Publications: Madrid, Spain, 2003; ISBN 978-92-844-0438-4. [Google Scholar]

- Birkett, D. Are You a Tourist or a Traveller? The Guardian. 2002. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2002/aug/24/ecotourism.guardiansaturdaytravelsection (accessed on 14 October 2017).

- Plakioti, E. Alternative Tourism Forms: Maritime Tourism and the Legal Framework. Master’s Thesis, University of Piraeus, Athens, Greece, 2013. Available online: http://dione.lib.unipi.gr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/unipi/8313/Plakioti_Elisabet.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 14 June 2018).

- Stratigea, A.; Papakonstantinou, D.; Giaoutzi, M. ICTs and tourism marketing for regional development. In Regional Analysis and Policy—The Greek Experience; Coccosis, H., Psycharis, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 315–333. ISBN 978-3-7908-2085-0. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. eTourism: Information Technology for Strategic Tourism Management; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 0582 35740 3. [Google Scholar]

- Katsoni, V.; Stratigea, A. Tourism and Culture in the Age of Innovation; Katsoni, V., Stratigea, A. , Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 2198-7246. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Adopted by the General Conference at its 7th Session Paris, France. 16 November 1972. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- UNESCO. Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. Adopted at the General Conference of UNESCO in Paris, France, 15 October–3 November 2001. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001429/142919e.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2017).

- Secretary-General of the UN; UNCLOS. Adopted at the 3rd United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, Montego Bay, Jamaica, 16 November 1994. Available online: http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Commission of the European Communities. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. European Agenda for Culture in a Globalizing World. Brussels, Belgium, 10 May 2007. COM 242. 2007 (Final). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2007:0242:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 17 October 2018).

- Commission of the European Communities. Communication from the Commission. Agenda for a Sustainable and Competitive European Tourism. Brussels, Belgium, 19 October 2007. COM 621. 2007 (Final). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52007DC0621&from=EN (accessed on 21 October 2018).

- Commission of the European Communities. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Europe, the World’s No 1 Tourist Destination—A New Political Framework for Tourism in Europe. Brussels, Belgium, 30 June 2010. COM 352. 2010 (Final). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52010DC0352&from=EN (accessed on 29 October 2018).

- Council of Europe. European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage (Revised). Adopted in Valetta, Italy. 16 January 1992. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168007bd25 (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- Council of Europe. The European Landscape Convention. Signed by the Member States of the Council of Europe in Florence, Italy. 20 October 2000. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680080621 (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Council of Europe. Chart of signatures and ratifications of Treaty 176. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/176/signatures?desktop=true (accessed on 13 February 2019).

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. Signed by the Member States of the Council of Europe in Faro, Portugal. 2005. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 16 November 2018).

- UN. The Barcelona Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean; Contracting Parties of the UN: Barcelona, Spain, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Panagou, N.; Kokkali, A.; Stratigea, A. Towards an Integrated Participatory Marine and Land Spatial Planning Approach at the Local Level—Planning Tools and Barriers Involved. Reg. Sci. Inq. 2018, 5, 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. An Integrated Maritime Policy for the European Union. Brussels, Belgium, 10 October 2007. COM 575. 2007 (Final). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52007SC1279:EN:HTML (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Commission of the European Communities. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Blue Growth—Opportunities for Marine and Maritime Sustainable Growth. Brussels, Belgium, 13 September 2012. COM 494. 2012 (Final). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/sites/maritimeaffairs/files/docs/publications/blue-growth_en.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- European Parliament; European Council. Directive 2014/89/EU: Establishing a Framework for Maritime Spatial Planning. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, L257, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management in the Mediterranean. Adopted by the Council of Europe Madrid, Spain. 21 January 2008. Available online: https://www.pap-thecoastcentre.org/pdfs/Protocol_publikacija_May09.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2018).

- Dellaporta, K. Underwater Cultural Heritage in Greece—Legal Protection and Management, Law and Nature. Available online: https://nomosphysis.org.gr/10093/upobruxia-arxaiologiki-klironomia-stin-ellada-nomiki-prostasia-kai-diaxeirisi-noembrios-2005/ (accessed on 23 December 2018). (In Greek).

- Law 3028/2002. For the Protection of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in general, 153/A/2002. Available online: http://www.tap.gr/tapadb/files/nomothesia/nomoi/n.3028_2002.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2018). (In Greek).

- Ioannou, K.; Stratis, A. The Law of the Sea; Law Library Publications: Athens, Greece, 2000; ISBN 9789605622039. [Google Scholar]

- Law 3409/2005. Diving and Other Provisions, 273/A/2005. Available online: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-naytilia-nausiploia/kataduseis-anapsukhes/n-3409-2005.html (accessed on 14 July 2018). (In Greek).

- Kounani, A.; Skanavi, K.; Koukoulis, A.; Maripas-Polymeris, G. Diving Tourism as a means for Promoting Sustainable Management of Coastal Regions—The Role of Diving Trainers. In Proceedings of the 7th National Conference on Management and Improvement of Coastal Zones, Athens, Greece, 20–22 November 2017; pp. 89–100. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Law 4179/2013. Simplification of Procedures for Enhancing Entrepreneurship in Tourism, Restructuring of the Hellenic Tourism Organization and Other Provisions, 175/B/2013. Available online: http://www.pde.gov.gr/ppxsaa/content/files/nomothesia/FEK_175_%CE%91_2013.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Law 1126/1981. Ratification of the 1972 UNESCO Convention on the “Protection of the World Natural and Cultural Heritage, 32/A/1981. Available online: http://portal.tee.gr/portal/page/portal/SCIENTIFIC_WORK/files/N1126.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2018). (In Greek).

- Law 1127/1981. European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage, 32/A/1981. Available online: http://portal.tee.gr/portal/page/portal/SCIENTIFIC_WORK/files/N1126.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2018).

- Law 3378/2005. European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage (Revised Version), 203/A/2005. Available online: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-arxaiotites/n-3378-2005.html (accessed on 26 August 2018).

- Leros. Available online: http://leros.homestead.com/geographyGR.html (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Areianet. Available online: http://www.hri.org/infoxenios/english/dodecanese/leros/ler_map.html (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Kostopoulos, D. Leros’ Travel Guide; Toubis Publications: Athens, Greece, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lerosisland.gr. Available online: https://lerosisland.gr/ (accessed on 22 June 2018).

- Collings, P. Leros Shipwrecks. Leros Active, 2008. Available online: http://lerosactive.com/main/images/2014-LEROSACTIVE-EBOOK.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2018).

- Spilanis, J. European Island and Political Cohesion; Gutenberg: Athens, Greece, 2012; ISBN 978-960-01-1544-4. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N.; Garrett-Petts, W.F.; MacLennan, D. Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry—Introduction to an Emerging Field of Practice. In Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry; Duxbury, N., Garrett-Petts, W.F., MacLennan, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–42. ISBN 978-1-138-82186-6. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Somarakis, G.; Stratigea, A. Smartening up Participatory Cultural Tourism Planning in Historical City Centers. J. Urban Technol. 2018, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawhall, N. The Role of Participatory Cultural Mapping in Promoting Intercultural Dialogue—‘We Are Not Hyenas’; Concept Paper Prepared for UNESCO; United Nations Education, Scientifi c and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, M.; Australian Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation. Valuing Cultures: Recognizing Indigenous Cultures as a Valued Part of Australian Heritage; Australian Government Public Service: Canberra, Australia, 1994; ISBN 0644328452. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, H.S.; Prosperi, D. Citizen Participation and Internet GIS—Some Recent Advances. Comput. Environ. Urban 2005, 29, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A. Theory and Methods of Participatory Planning [online]. Hellenic Academic Electronic Books, Kallipos: Athens, Greece. 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11419/5428 (accessed on 14 September 2018). (In Greek).

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A. Spatial Data Management and Visualization Tools and Technologies for Enhancing Participatory e-Planning in Smart Cities. In Smart Cities in the Mediterranean—Coping with Sustainability Objectives in Small and Medium-sized Cities and Island Communities; Stratigea, A., Kyriakides, E., Nicolaides, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 31–57. ISBN 987-3-319-54557-8. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsi, D. Integrated Management of Land and Underwater Cultural Resources as a Pillar for the Development of Isolated Insular Islands. Master’s Thesis, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 20 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, S.; Ritchie, B.; Timur, S. Measuring destination competitiveness: An empirical study of Canadian ski resorts. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2004, 1, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, F.B.; Wechler, B. State agencies’ experiences with strategic planning: Findings from a national survey. Public Admin. Rev. 1995, 55, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, F. Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-1292016894. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhanen, L. Destination competitiveness: Meeting sustainability objectives through strategic planning. In Advances in Modern Tourism; Matias, A., Nijkamp, P., Neto, P., Eds.; Physica-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 133–151. ISBN 978-9-7908-1717-1. [Google Scholar]

- Stratigea, A.; Giaoutzi, M. ICTs and local tourist development in peripheral regions. In Tourism and Regional Development: New Pathways; Giaoutzi, M., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Ashgate: Farman, UK, 2006; pp. 83–98. ISBN 978-135-187-862-3. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism and sustainable development. In Global Tourism: The Next Decade; Theobald, W., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 274–290. ISBN 978-0750623537. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C. Strategic planning for sustainable tourism: The case of the offshore islands of the UK. J. Sustain. Tour. 1995, 3, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, M. The study of the futures: An overview of futures studies methodologies. In Interdependency between Agriculture and Urbanization: Conflicts on Sustainable Use of Soil Water; Camarda, D., Ed.; CIHEAM: Bari, Italy, 2001; pp. 439–463. ISBN 2-85352-222-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rhydderch, A. Scenario Planning, Guidance Note; Foresight Horizon Scanning Centre: London, UK, 2009. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140108141323/http://www.bis.gov.uk/assets/foresight/docs/horizon-scanning-centre/foresight_scenario_planning.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2018).

- Sardar, Z. The Namesake: Futures, Futures Studies, Futurology Futuristic, Foresight—What’s in a Name? Futures 2010, 42, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, M.; Bandhold, H. Scenario Planning: The Link between Future and Strategy; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-333-99317-0. [Google Scholar]

- Olsmats, C.; Kaivo-Oja, J. European packaging industry foresight study—Identifying global drivers and driven packaging industry implications of the global megatrends. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2014, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A.; Papadopoulou, C.A.; Panagiotopoulou, M. Tools and Technologies for Planning the Development of Smart Cities: A Participatory Methodological Framework. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Legal Instruments. Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. Paris, 2 November 2001. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/eri/la/convention.asp?KO=13520&language=E&order=alpha (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Balint, P.J.; Stewart, R.E.; Desai, A.; Walters, L.C. Wicked Environmental Problems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-61091-047-7. [Google Scholar]

- Leidwanger, J.; Daniels, I.B.; Greene, S.E.; Leventhal, M.R.; Tusa, S. Implementing Underwater Cultural Heritage ‘Best Practices’ in the Mediterranean: The Noto meeting and Statement. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 2014, 43, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Somarakis, G.; Stratigea, A. Participatory Spatial Planning in Support of Cultural-Resilient Resource Management: The Case of Kissamos-Crete. In Mediterranean Cities and Island Communities: Smart, Sustainable, Inclusive and Resilient; Stratigea, A., Kavroudakis, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-99443-7. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, C.A.; Stratigea, A. Traditional vs. Web-based Participatory Tools in Support of Spatial Planning in ‘Lagging-behind’ Peripheral Regions. In Socio-Economic Sustainability, Regional Development and Spatial Planning: European and International Dimensions and Perspectives, Proceedings of the International Conference of the Department of Geography and University of the Aegean, Mytilene, Greece, 4–7 July 2014; Korres, G., Kourliouros, E., Tsobanoglou, G., Kokkinou, A., Eds.; Department of Sociology—University of the Aegean, International Sociological Association: Mytilene, Greece, 2014; pp. 164–170. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | Noto’s workshop: held in Sicily/Italy, 17–19October 2013 and titled ‘EUPLOIA: Implementing Underwater Cultural Heritage ‘Best Practices’ in a Mediterranean Context’. |

| Rating of Scenarios | % | Rating of Priority Axes | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | Designation of local cultural identity as a pillar for economic development and social cohesion | 45 |

| Treatment of land and underwater cultural heritage in an integrated way | 27 | ||

| Integrated approach of natural and cultural resources | 21 | ||

| Leros Island in Scenario A’ “From a ‘Soul -House’ to a place of Multiple Opportunities” | Development of alternative, experience-based, cultural tourism products | 35 | |

| 64 | ICT-enabled promotion of land and underwater cultural heritage | 16 |

| Enhancement of local entrepreneurship and creation of value chains | 19 | ||

| Raising awareness of local community on the value of natural and cultural resources | 28 | ||

| Leros Island in Scenario B’ “An ’Open Museum‘ of European Cultural Heritage and Identity” | |||

| Balanced cultural tourism development—removal of inequalities | 30 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Unburying Hidden Land and Maritime Cultural Potential of Small Islands in the Mediterranean for Tracking Heritage-Led Local Development Paths. Heritage 2019, 2, 938-966. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2010062

Koutsi D, Stratigea A. Unburying Hidden Land and Maritime Cultural Potential of Small Islands in the Mediterranean for Tracking Heritage-Led Local Development Paths. Heritage. 2019; 2(1):938-966. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoutsi, Dionisia, and Anastasia Stratigea. 2019. "Unburying Hidden Land and Maritime Cultural Potential of Small Islands in the Mediterranean for Tracking Heritage-Led Local Development Paths" Heritage 2, no. 1: 938-966. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2010062

APA StyleKoutsi, D., & Stratigea, A. (2019). Unburying Hidden Land and Maritime Cultural Potential of Small Islands in the Mediterranean for Tracking Heritage-Led Local Development Paths. Heritage, 2(1), 938-966. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2010062