3.1. Interventions

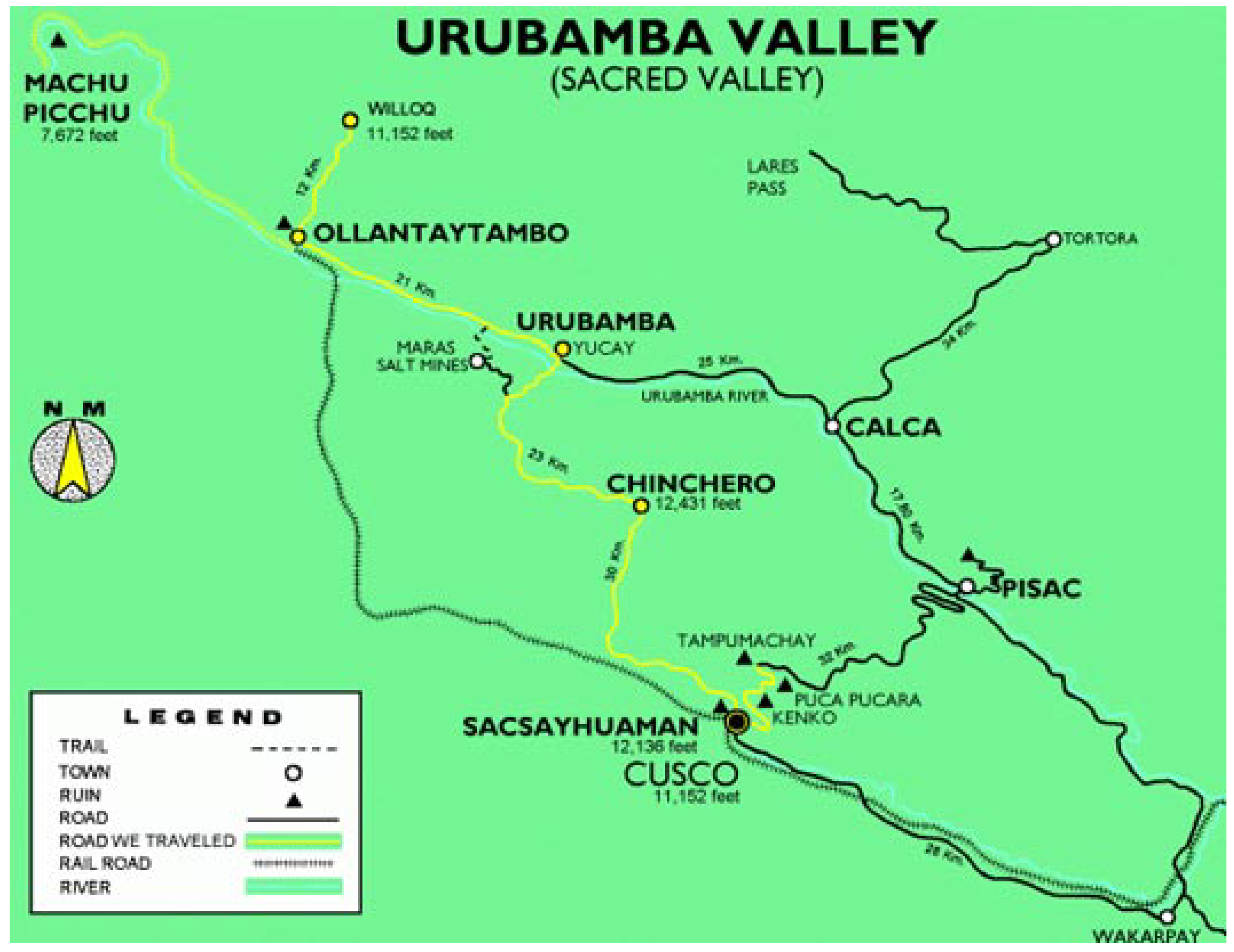

Between 1975 and 1980, UNESCO promoted the PER-39 project in southern Peru, under the direction of cusqueñan architect Roberto Samanez with his team. Samanez had studied monumental restoration in Rome. According to him, the project’s aim was the incorporation of the 1970 and 1972 UNESCO conventions in the Andes through the puesta en valor of the archaeological heritage contained within the so-called Cusco-Puno corridor, a geographical and cultural axis that linked together these two important southern Peruvian cities. Both conventions targeted the generation of economic income through tourism. The Inca sites, like Ollantaytambo and Machu Picchu, located in the sacred valley of the Urubamba River, fell within the project’s area of influence. In those years, with the support of the INC or National Institute for Culture (currently the Ministry of Culture), and the funding from the United Nations, the COPESCO Special Project (or Plan COPESCO) was implemented. COPESCO relied on the equation between tourism and economic development by means of the puesta en valor of monuments.

It was not the first time that restoration work had been carried out on site. Already in 1936, Peruvian archaeologist Luis Llanos had partially cleared out the fortress and consolidated small portions of it. Also, another national archaeologist, Luis Pardo, did minor excavations in 1937, 1946 and 1957. After that, INC-COPESCO did restoration in Ollantaytambo in two different phases: between 1980 and 1982 the ceremonial sector was restored and

puesto en valor, and Qosco ayllu was upgraded. A second phase, executed by COPESCO between 1993 and 1998, concentrated on Qosco Ayllu. The novelty of these interventions, as Protzen [

14] has noted, rested on the new scale of reconstruction, well beyond mere previous consolidation, reparation or restoration activity.

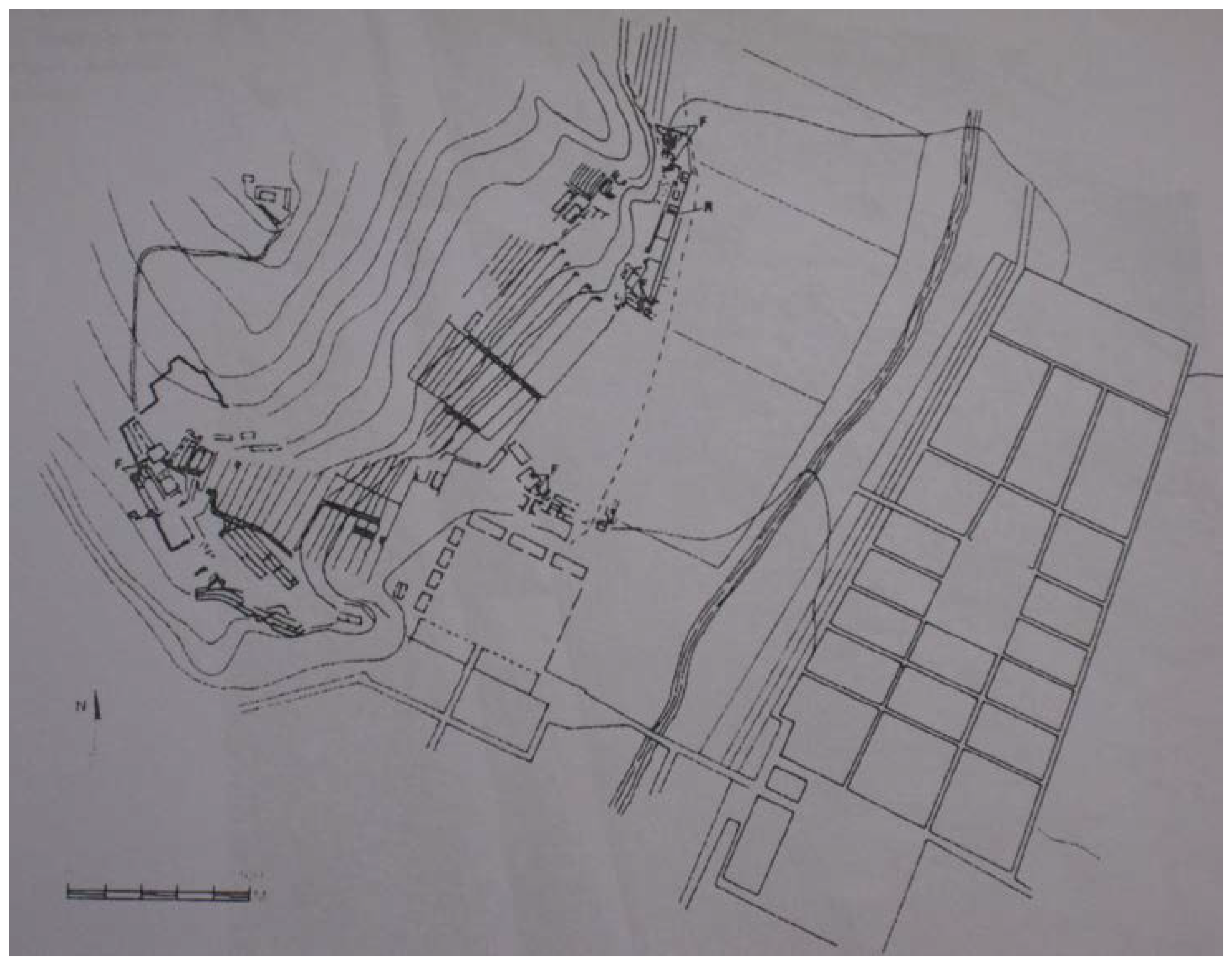

Archaeologist Arminda Gibaja was in charge of the 1980–1982 intervention, with a focus on conservation. The objects of the intervention were the lower sectors within the ceremonial area known as Inkamisana and Manyaraqui, where the original Inca plaza had once stood (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). In her final report [

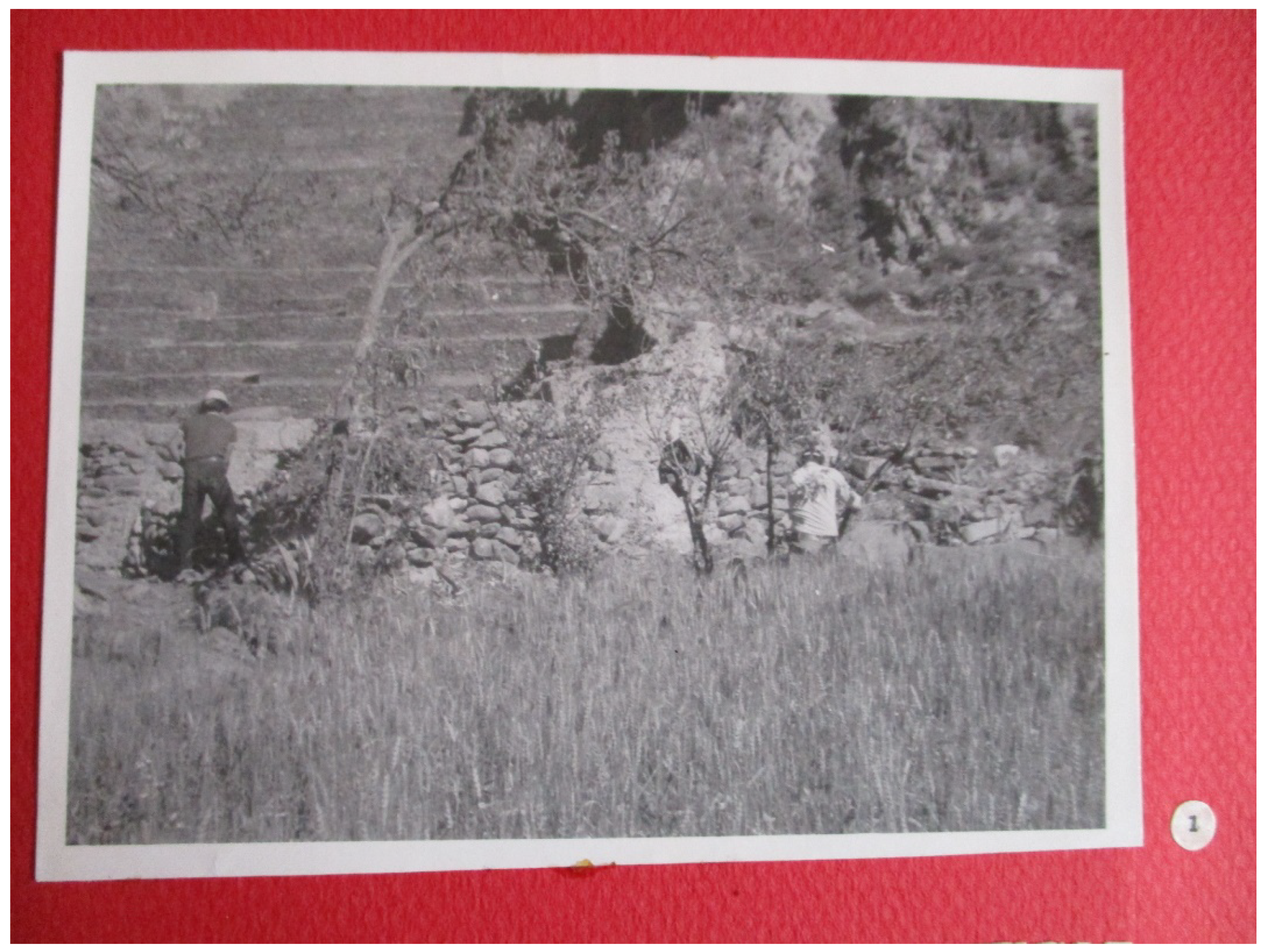

9] she described these sectors’ condition prior to the works. Unless otherwise indicated, the information that follows in the next three paragraphs comes from this report. Parts of these sectors had become by then private property, which made things more complicated. She referred to Inkamisana as a cluster of fenced agricultural parcels in the middle of which many lithic elements stood and could not be moved because of their size and weight. As for Manyaraqui, the place had been turned into a corral, and it stood in disarray. Walls had been dismantled and re-used for contemporary housing needs. Compared with the relatively good state of conservation of the fortress due to Llanos’ 1936 cleaning and maintenance work, she reported on the state of abandonment of a monumental area degraded by a combination of natural and human factors. Erosion caused by atmospheric conditions, plus the overgrowth of roots, vegetation, and trees, not only had damaged the physical structure and the materials, but it also prevented a view of the town from the fortress (

Figure 7). The complex of fountains in Manyaraqui was covered in mud due to slides and required excavation, cleaning, and restoration. Moreover, stones had fallen off their original structures and sometimes had been displaced. Such was the case with the temple’s doorway. In this and other cases, there was no way to know what their original position was. Residents were also uncertain whether it was a doorway in origin or just a niche. She went on to lament that a good part of the space had become agricultural fields where animals roamed and that even a bullring had been set up by the villagers at the entrance of the monument, using the Inca terraces as stands to accommodate the spectators.

Inkamisana and Manyaraqui had been occupied during colonial and contemporary times. Structures had changed in function. New windows and doors had been opened, whereas older ones had been closed or dismantled, following utilitarian criteria by the villagers. Many fences built to delimitate agricultural parcels had to be pulled down. Others were private and required future expropriation. In the fortress, previous interventions had implemented openings in walls to facilitate the tourists’ access and circulation. These openings did not exist before. Also, stairs had been built to facilitate access to the upper spaces. Under conditions of continuous reoccupation by residents, hearths had been accommodated in the original walls by hollowing them. Moreover, some walls had been pierced in the search for

tapados, or treasures believed to be hidden. For restoration purposes, wedging techniques were used. Gibaja’s team replaced the characteristic Inca binder made of clay and gravel with a mortar of lime, sand, and a small amount of concrete. Walls were restored by means of anastylosis, or the process by which a ruined building or monument is restored using the original architectural elements to the greatest degree possible (

Figure 8), according to the recommendations found in the international charters, particularly the 1964 Venice charter. In Manyaraqui, wall heads were consolidated with covers in order to avoid further damage caused by the rain and other adverse atmospheric conditions.

The intervention also affected Qosco Ayllu. Here, there was a different set of issues, as the sector had been uninterruptedly inhabited, and contemporary families had construction and maintenance needs that often conflicted with conservation principles in an area declared to be an archaeological zone and therefore inalienable. This declaration as an archaeological zone revealed the temporal and practical frictions and contradictions inherent in the patrimonialization of historic spaces, as it involved that contemporary needs remained subordinated to the study and the public presentation of the past. It also meant that residents had little control over their living compounds, which in turn exacerbated existing tensions between them and the institutions’ representatives. A local tourist guide expressed this frustration when the author talked to him: “The Ministry of Culture makes it very difficult for us to implement any changes in our homes, but if it is somebody with money they turn a blind eye.” COPESCO wanted to upgrade Qosco Ayllu in terms of the provision for running water, a sewage system and drainage, street paving, and more. This meant restoration and excavation activity. In practice, it entailed a thorough cleaning of all vegetation affecting structural and architectural elements, the recording of overlapping architecture during different occupation phases, and excavations to determine variations of use and function in the sector throughout time. COPESCO conceived of Qosco Ayllu as a great urban historical archive, but at the expense of the residents’ needs, which threatened the supposed integrity of the urban core. Conceiving of this core as a historical archive risked encouraging processes of museumification and commodification of peoples and places. It also deepened the disjunction between the present and the contemporary past. Furthermore, it favored the stigmatization of the residents’ practices—otherwise driven by pragmatic logic—as highly damaging and irrespective of their own heritage. For example, in that part of the project aimed at rehabilitating streets and restoring doorways and that involved the restoration of one particular kancha (4–34), residents were blamed for the lack of care and maintenance. Here, restoration tasks amounted to identifying the conservation state of all kancha elements, as well as to eliminating or demolishing foreign elements that did not belong to its original condition.

If the first stage of Plan COPESCO had focused on the restoration and

puesta en valor of the ceremonial center, as well as on the upgrading of Qosco Ayllu, the second stage, started in 1993, integrally concentrated on Qosco Ayllu, as detailed in the intervention report [

15]. According to this document, the main declared objectives were: (a) to complement the process of

puesta en valor initiated in the first stage; (b) to strengthen the touristic potential of the Sacred Valley of the Incas, presenting to the visitor the only original Inka town that continued to be inhabited by the peasants.

Besides its architectonic and archaeological focus, the project expressed a concern for the socioeconomic factors that contributed to the perceived depredation of the architecture. Among these was the increase of young families, which caused the hovelling of the

kanchas, the intentional destruction of Pre-Hispanic sheds to accommodate free spaces, as well as changes in function and uncontrolled contemporary buildings. One more factor of depredation was the lack of areas for urban expansion due to the presence of agricultural terraces. Consequently, land invasions were frequent in the archaeological zone. The document states the necessity of formulating rules that enabled a continued use of the

kanchas in a ‘rational’ manner by current dwellers [

9]. However, this only evinces that ‘rationality’, as far as relationships with the material past and uses of space were concerned, was understood differently by rural dwellers with a strong sense of territoriality, and by heritage professionals from an urban background.

3.2. International Conservation and Restoration Framework

Restoration work in Ollantaytambo did not happen in a vacuum. In fact, it was considerably influenced by a long history of conservation theory and practice, particularly in Europe. Architects and archaeologists who worked at the site had been trained in national universities where these theories and models from overseas were widely circulated and taught. Even more, some of the architects involved in the PER-39/COPESCO project had obtained grants to study abroad. This was the case with Roberto Samanez, the project’s director, who had studied monumental restoration, as well as Classical and Renaissance mural painting restoration, in Rome. According to Samanez, with money from the United Nations, COPESCO funded training courses on restoration and conservation of monuments for architects and archaeologists, as well as another course on artwork restoration for restorers. ICCROM (The International Center for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property) was in charge of the training. All these circumstances, as illustrated later, were relevant to understanding the orientation that guided the interventions, as well as its impact on the site’s public presentation. In fact, the figure of the architect-restorer took on a stark significance in the whole project. They were, in theory, the only ones allowed to conduct restoration work on the site [

9,

15].

Following Jokiletho [

2], the Modern Conservation Movement, which establishes the contemporary social relevance of heritage and the main concepts and policies currently in trend, was the result of a long history of debates and practices. Its main principles of preservation had been delineated in 18th C. Europe and had its roots in the Italian renaissance, if not before. Some key factors were a new sense of historicity involving the separation between the past and the present, a romantic nostalgia for a lost past, as well as the shock created by the destruction encouraged by industrialization. An initial emphasis on restoration fostered by the French Revolution was countered by an anti-restoration movement that led to modern conservation, later strengthened by science and positivism. At its core was the recognition of cultural diversity and the relativity of values, which formed the basis for the definition of the concept of ‘national monument’ as part of a national heritage. However, from the beginning of the debates, different types of restoration practices coexisted at the same time, oscillating between the destruction/modification of ruins and their reconstruction. Principles of conservation evolved from an 1830s concept of conservative minimum intervention (based on careful archaeological study) to a more ‘drastic’ complete restoration by the middle of the 19th century. At that time, debates revolved around questions such as how far should restoration go or if mutilations and traces of time should be repaired or not. Viollet-le-Duc´s influential theory of ‘stylistic restoration’ was accepted in France and abroad. It postulated the reinstating of a building to its ideal pre-existing form and in its original style, no matter the changes it had undergone through history. Respect for the original forms was required, but not necessarily for the materials. In practice, this meant that modern materials could be used to undergird ancient buildings. Attention should be paid not only to appearance, but also, and particularly, to structure [

2].

While Viollet-le-Duc gained worldwide recognition in the second half of the 19th C., others regretted the loss of the patina of time in historic buildings. In England, Ruskin and Morris reacted against what they considered the destruction of the historical authenticity of the buildings and advocated the defence of their material truth. Historic alterations and additions should be preserved, under the new guiding principles of conservative repair and the staving off decay by daily care. No imitation or copying was justified except for preserving records of great works. For these theorists, age contributed to the beauty of the work of art, thus placing a major accent on historicity while at the same time highlighting the limits of scientific restoration and its technical abuses [

2].

Since then, minimum intervention has been widely recommended. Central to 20th C. theory, yet probed over the last two decades, has been the concept of preserving the ‘integrity’ and ‘authenticity’ (or originality) of the monument through science [

1]. Current state-of-the-art strongly emphasizes cultural relativity and diversity in order to adapt these concepts to heterogeneous historical traditions. Yet, at the same, the value of universality remains one of the pillars of heritage theory. Science and technology have taken on a prominent role in restoration initiatives. This has substantially increased the scope and range of interventions thanks to the knowledge gained and the new methods implemented in conservation; but, on the other hand, it has raised objections when technology has inhibited the use of traditional methods and materials, impinging on the sense of authenticity. Modern trends in conservation largely rest on the debate between historical authenticity and historical continuity. The latter recognizes the need to safeguards living cultures and traditional know-how, and thus implies the acceptance of change as an essential principle in the process [

2].

Influential theorists like Brandi have been a reference for international charters on conservation and restoration and conservation bodies like ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites), from which general conservation and restoration guidelines have emanated. These charters, particularly Venice, have strongly discouraged reconstruction, unless there is complete and elaborate evidence of the original state [

16]. Brandi’s main idea is that restoration, understood as historical process, and as opposed to reconstruction, should avoid pretensions to reverse time or abolish history. Consequently, the idea of returning a building or painting to its ‘original’ state is a misguided one. Not surprisingly, Brandi expressed concerns with misconceived restoration often carried out in archaeological sites, which involved the falsification of the artistic concept by misinterpreting its proportions, surface treatments, or materials [

2]. This is relevant for the case of Ollantaytambo, insofar as the interventions targeted in this study suffered from such misconceived actions. In particular, restoration on site was notably influenced by Viollet-le-Duc’s theories that promoted the return of a construction to its supposed original form, no matter what materials and techniques were used. These theories served well the goals of a growing tourist industry that heavily relied on notions of a de-historized authenticity to attract cultural tourism to the area.

3.3. Interventions Challenged

This section draws heavily from a couple of interviews held with Martín Barrios, senior archaeologist from the Ministry of Culture’s office in Ollantaytambo. The first interview was conducted on site, while walking around the ceremonial sector and Qosco Ayllu. It was expanded by a second interview in Cuzco a few days later. Other voices from professionals involved in the PER-39 project joined in the conversation along the way.

Barrios was very critical of restoration work carried out on site and of the criteria followed. For the ceremonial sector (Inkamisana) he pointed out a number of flaws. Particularly, the use of mortar, gravel, and lime, which had obliterated the yellowish mortar used by the Incas. This was against the international charters for conservation and restoration (Venice 1964), and on authenticity (Nara 1994) [

17]. Its effects on the stone were the formation of a patina or black stain (

Figure 9). “It was an abuse”, Barrios said, “an exaggerated reconstruction, sometimes without formal basis or serious evidence”. In his view, the use of lime was a mistake. In the past, it had been applied in the restoration of Machu Picchu to provide stability and durability, even if it was alien to the original material. However, its use had only triggered stone degradation as well as the appearance of fungi and lichens. For Barrios, the reconstruction process in Inkamisana had altered Inca stereotomy by using flat stone from outside of Ollantaytambo. Consequently, there was no way to differentiate the original from the reconstructed, and that he considered a bad criterion based on the charters’ recommendations.

For Barrios, the goal of restoration had been displaying the site as an Inca monument. He noted the paradox embedded in the fact that, while Ollantaytambo was a historically unfinished site, some reconstructions had been completed. In his view, this kind of restoration had distorted the message, vision, and method of Inca architecture. Ollantaytambo not only was an Inca site; it also featured pre-Inca, colonial, and republican remains. Yet, for the archaeologist, the different construction phases and historic periods on site had been neglected, and there had not been a specific treatment for each of these. Rather, they all had been subjected to the same generic intervention. This was relevant insofar as the different ethnic groups from different parts of the empire that had worked in the site including the yanacona or servants [

14], each with their distinctive construction techniques, had left a trace on it.

Barrios brought up additional issues during our tour of the ceremonial area. For example, the presence of decontextualized stones at the entrance of the ceremonial sector. Also, the arbitrary use of modern materials like concrete and PVC that were very convenient and easy to handle but did not look good. Furthermore, the ‘reinvention’ or ‘fabrication’ of some fountains in Manyaraqui whose flow of water had been manipulated to please the tourist (

Figure 10). Besides this, a questionable use of anastylosis, without proper evidence of the original material, as well as the use of protection covers for ancient structures that tended to be confused with original roofs (

Figure 11).

In Qosco Ayllu, Barrios identified another set of problems. Apart from the undue use of concrete in some places, mortar had been employed in walls, when in Inca times these were stuccoed and showed no angles or straight lines like now (

Figure 12). He judged this effect misleading for the tourist. Equally misleading, in his view, was the fact that right in the middle of the urban grid a non-Inca block stood. COPESCO had silenced this circumstance. One more issue pointed out was the labor force. For the archaeologist, the technicians wanted to emulate or even surpass Inca construction techniques. The consequence was confusion between the past and the present. Yet the main problem with the intervention had been the general lack of planning and of adequacy to a rapidly changing urban sector that experienced fragmentation in its physical and social fabric. A growing population, as well as mounting touristic pressure, had multiplied the demand for housing and business spaces, giving way to inheritance disputes within families. Many families wanted an extra story built in their two-story houses, which went against existing urban regulations dictated by the problematic characterization of Qosco Ayllu as a ‘historic center’. In fact, the case of other renowned historic districts in the region such as Cuzco or Chinchero, affected by similar problems as those just described, and others, only confirm the tendency in these emblematic spaces where patrimonialization and tourism development alike often lead to gentrification, loss of traditional lifestyles, and dereliction [

4,

10].

Truth is that Barrios was not alone in the formulation of charges against restoration work on site. US archaeologist J.P. Protzen, the author of an important and well-known study on the Inca architecture of Ollantaytambo [

14], has also expressed serious concerns regarding the interventions. Apart from disapproving the new scale of reconstruction, his view is that structures were redesigned and reconstructed with little care for existing evidence. (Self) criticism has also come from Samanez and Américo Carrillo, another architect-restorer and member of Samanez’s team at the time. Samanez was in agreement with Barrios in that anastylosis should have been performed differently. This method is recommended in the Venice Charter. However, for the architect in charge of the PER-39 project, this work had been done without evidence, following the questionable example of past restorations in Machu Picchu. Carrillo recognized that using lime in Ollantaytambo had been a bad idea. However, when interviewed in Cuzco, Gibaja insisted that the interventions had been carried out within the referential framework of the international charters.

During the conversations with Barrios, a number of relevant issues had come up. First, there was the relevant role in the interventions of the architect-restorer. Both Samanez and Carrillo were architect-restorers with a background in restoration. As it has been noted, the former had studied monumental restoration in Rome, where he had also been trained in classical and renaissance mural painting. Carrillo too had been exposed to mural painting theory. This matters because architect-restorers were the professionals specifically appointed by UNESCO to oversee the PER-39 interventions in Ollantaytambo. The reason for this preference, as Carrillo explained, was that, as opposed to archaeologists and other professionals entitled to restore, the architect-restorer possessed a richer conceptual background and was more aware of the different trends and schools. Clearly, this preference only reinforced the artistic and aestheticized bent that informed UNESCO’s approach to restoration work.

This differentiation made full sense within the (ongoing) profound professional antagonism in Cuzco between architects and archaeologists. For the latter group, the former had no respect for the historical authenticity of the building and took the liberty to modify it without historical research being done. Nevertheless, if the original focus, as the Venice Charter recommended, was on restoration and consolidation rather than on reconstruction, things did not go that way in the end, and reconstruction seemed to have prevailed over restoration in the ceremonial center. “We had problems with our workers and technical staff”, Samanez acknowledged. “We had to teach them the difference between restoration and reconstruction, let alone reconstruction that could be misleading or that was merely based on a hypothesis.”

The idiosyncrasy of the labor force had been one factor at play. However, there were more. Barrios pointed out, as a distinctively cusqueñan feature, the highly individualistic profile of the professionals in charge of the interventions, be it architects, archaeologists or anthropologists, usually in a context of great rivalry and competition among them. Each of them exercized a large degree of autonomy and would organize ‘schools’ of workers around them. Their methods would then be transferred to their workers. According to Barrios, the authority of these professionals had great repercussions in restoration works. This peculiar configuration of schools was also played out at the national level. In Lima a similar pattern did exist. ‘Schools’ were formed around renowned archaeologists or even around institutions like the Pontificia Universidad Católica and the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. At stake here was the prestige of Lima with regard to Cuzco. Barrios acknowledged that limeñan universities placed a greater emphasis on theory and methods compared to their cusqueñan counterparts.

Further reasons that had an impact on the works on site were mentioned in passing by Barrios. These included a lack of budget that prevented the Institution from hiring more workers, and the fact that restoration works were guided by civil construction criteria, in the sense that restoration work hours were measured in terms of ordinary labor performance. In practice, this meant that there was no distinction in terms of budget between one activity and the other.

Both Barrios and Carrillo agreed in that a monumentalism inspired in European models had prevailed due to the leading role of the architects-restorers in the interventions in Ollantaytambo. Particularly, the influence of Viollet-le-Duc’s structuralism (or stylistic restoration) was strongly felt. For this school, what mattered, apart from the physical appearance, was maintaining the original form of a building, to reinstate it to a state of completeness that might have never existed before. Seeking for a unity of style, alterations in the form of the removal of later additions and modifications of the original were justified, as was the use of new materials to support the structure [

2]. Carrillo put it this way:

“Because of my background in restoration, I learned the structural intervention. Altering the material was not a problem. For example, you could insert iron in a Pre-Hispanic or colonial building as long as the ideal form was preserved. Monumentalism was the dominant paradigm in those times.”

Samanez’s and Carrillo´s background in (Italian) mural painting had implications for the site’s restoration. Miranda thought that their Italian background had translated into distortions and transgressions. Monumentalism and the use of lime had been some of them. Yet there was also a mural painting component involving the use of chemicals in the treatment of walls. These procedures differed from a specific Andean lithic technology based on a religious respect for the material. As the author saw it, it was also about (mis) conceptualizing Inca walls as 2-D flat surfaces, downplaying the highly tactile, sensorial, and spatial quality of a 3-D Inca architecture that actively and intentionally engages the various senses apart from the visual (see Nair [

18]). Considering this 2-D approach to restoration, it could be argued that the European representational tradition, along with the prominent role of photography in contemporary mass tourism, have contributed to (re)producing a postcard version of Inca architecture in the site. This can hardly be surprising considering the nearby presence of Machu Picchu, one of the most photographed and reproduced monuments in the world.

3.4. Machu Picchu

Barrios, Samanez, and Carrillo had stressed the ideal of the (Inca) monument underpinning restoration practices in Ollantaytambo, as if this ideal was a given. However, the concept of the ‘monument’ had been historically produced [

19]. Originally coming from the Greek word

mneme (memory, memorial), with the Latin voice

monumentum it had acquired moral and political connotations, as if to admonish and remind the spectators of the power of the governors [

2]. At the turn of the 20th C., the Austrian philosopher Alois Riegl reflected on what he called the “modern cult of the monument”. He made a distinction between the ‘intentional’ and the ‘unintentional’ monument. The former, proper to pre-modern peoples, had in origin an intention to remember and keep the memory alive; the latter, inaugurated with the Renaissance, had no commemorative value. Rather, its values were subjective and constructed within the framework of Western art and history [

13]. Almost anything that revealed the passage of time could be a monument, and fragility, as opposed to permanency, was its hallmark. If in the intentional monument age was an obstacle in its attempt to overcome temporal distance, the unintentional one, imbued with a modern age-value and a sense of loss, was in essence a historical object, split by the irreversible divide between the past and the present and therefore subject to become ‘heritage’ [

13].

If there is nowadays a true Inca, ‘unintentional’ (in Riegl’s sense) monument, that is, of course, Machu Picchu, which in origin was a memorial, like much Inca imperial architecture. The ascendancy of Machu Picchu’s reconstruction over Ollantaytambo’s deserves further exploration. Both Barrios and Carrillo had pointed out the large-scale reconstruction program at Machu Picchu. Their estimates matched: about 70% percent of what we see today in the famous Inca site has been (arbitrarily) reconstructed. Machu Picchu’s influence on the cusqueñan imaginaries was (is) huge.

Incanismo, which grounds the past and present greatness of Cuzco in a largely imagined Inca identity built around the material remains of the Pre-Hispanic past, cannot be understood without it. Luis Valcárcel [

20], one of the most influential

indigenistas, had established a canonical view of Machu Picchu in his writings: it was a sacred city, the culmination of Inca culture, as well as place for communion with the cosmos. Its condition as marvel of the world was simultaneously reinforced and legitimized by international tourism. Barrios articulated this feeling in an idiosyncratic manner: “We are

machupichhólogos”, meaning that Machu Picchu had been constructed in the cusqueñan imaginaries as the epitome of Incanness (an operation that had been successful from the point of view of tourism). “Our minds have been instilled with

incanismo, with regionalism, hence our chauvinism”, he said. Consequently, Machu Picchu’s reconstruction and presentation paradigm had impregnated all other interventions at the regional level. A site as close to it and as iconic as Ollantaytambo could not have possibly escaped Machu Picchu’s spell. Barrios confirmed: “The criterion was to make the site as Inca as possible”. In practice, following one of

indigenismo’s main tenets regarding restoration, as Carrillo informed me, this entailed the removal of all colonial elements from Pre-Hispanic constructions. Coincidentally, at the time this was also the structuralist position that had driven Gibaja’s and Carrillo’s involvement with the PER-39 project.

If, as I have explained, Machu Picchu’s ascendancy had a considerable influence on the interventions in Ollantaytambo, an issue to be explored in more detail at this point is what forces contributed to construct Machu Picchu as an Inca icon since its ‘discovery’ in 1911. Following Cox [

21], the University of Yale’s expedition led by Hiram Bingham had had the ultimate goal of collecting artefacts for their own collections. To legitimate that purpose, the expedition relied on the universal virtue and authority of science. Therefore, science (archaeology) was the first step in making Machu Picchu visible as a monument, and thus collectible. Through clearing, reconfiguration, and reconstruction of the now rediscovered ‘lost city’, time had to be disappeared to make it a timeless, ahistorical monument worthy of science [

21]. Another scientific, objective, and widely used practice in Bingham´s expedition, namely photography, not only helped to circulate Machu Picchu worldwide; it conjured up as well a specific framework of the city as “lost and hidden behind the ranges” [

21] (p. 250). For Cox [

22], photography, as a potent fixer of people and history, brought Machu Picchu into what Salvatore [

23] (see also Gómez [

24]), when discussing the reliance on representational practices of informal, hegemonic empires, has called “the dominant field of visibility”.

This point will be further developed later. For now, it seems, then, as if Machu Picchu had been intentionally ‘fabricated’ as an Inca ruin and that this fabrication that had started with science and photography had been later continued by

incanismo, restoration, and tourism development. Machu Picchu’s ‘invention’ is not by any means an exception. Examples are not lacking for ‘fabricated’ monuments in the Andes as well as elsewhere. In the Andes, a most notorious case is that of Posnansky’s reconstruction of Tiwanaku, in the Lake Titicaca basin, where a large-scale movement of stones from one place to another without evidence of their original position had occurred [

25]. In Europe, Cócola’s [

26,

27] study of the Gothic Quarter in Barcelona evinces the successful operation orchestrated by the city’s political and economic elites during the 20th C. This operation turned the neighborhood that surrounded the cathedral into a ‘gothic’ monument, following the stylistic restoration promoted by Viollet-le-Duc in the 19th C., a model that denied the character of the monument as historic document. The city elite’s agenda was twofold: first, to assert the Catalonian origins in the legendary Middle Ages; and second, to market Barcelona abroad as a first-class international tourist destination. Cócola [

26] points out that the tourist market and its rules gradually absorbed the political function of the fabrication. Another case in point is that of San Gimignano, a medieval village in Tuscany. Between 1920 and 1930, the town’s city center was subject to a heavy urban editing by Mussolini’s regime in fascist Italy [

28]. The goal was to make the town appear as authentically medieval as possible to suit an ideological rhetoric that, for convenient political reasons, imagined the Italian identity as located in that particular age. The regime favored the erasure of the intervening traces of later centuries through a restoration and reconstruction that was largely dependent on a touristic development agenda [

28]. If in Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter the same stylistic restoration criticized in the international charters was encouraged by the tourist industry [

27], something similar could be said of San Gimignano. In both cases, the operation entailed the fabrication of old destinations, as age-value had become a priced commodity in the market [

27].

If the ‘invention’ of monuments had served political and economic ends in Tiwanaku, Barcelona or San Gimignano, Machu Picchu, Ollantaytambo, and other Inca monuments ‘fabricated’ through puesta en valor abide by a similar logic. Incanismo is the political ideology that sustains this fabrication with its rhetoric of an Inca identity for contemporary cusqueñans, anchored in old ruins. It is the same ideology that led some workers in Ollantytambo, as Barrios recalled, to try to emulate and even surpass their Inca predecessors to make the site ‘as Inca as possible’. The tourist industry has capitalized on this rhetoric by promoting the value of ‘pastness’ in restoration projects. Samanez illustrated the point:

“We faced the opposition of the tourist agents. They did not like the fact that our restoration was not a replica or exact copy of the original. Their idea was returning to Inca, like in other interventions or even in Machu Picchu, where anastylosis had been applied without evidence of the original locations.”

3.5. Puesta en Valor and Tourism

The ‘dominant field of visibility’ was also at work in Ollantaytambo. The philosophy and practice of

puesta en valor was permeated by it, as it involved the conversion of ruins into (visible) monuments and their public presentation. After all, as Herring [

29] argues, Western comprehension of Inca art has revolved around matters of visibility and invisibility, of intelligibility and unintelligibility, insofar as the abstract character of Inca visual form has posed a considerable challenge to the iconic, textual, representational nature of western artistic tradition [

30,

8]. If, as Samanez and Barrios had concurred, Ollantaytambo was fabricated as a monument for the tourist, then, arguably, a homogenizing tourist gaze (see Urry [

31]) had silently informed restoration work to produce the site as distinctively ‘monumental Inca’ to be apprehended and consumed. The tourist gaze is heir to a Western visualism which, from a postcolonial standpoint [

23,

32,

33], has historically functioned as an ideological cognitive tool for incorporating the ‘other’ into Western political hegemony through various representational devices, such as maps, drawings, and books.

Barrios expressed deep concern about the processes of puesta en valor implemented in the Cuzco region in those years of the PER-39 project and thereafter. In his view, the problem not only was that they had drawn their inspiration from Europe as bad imitations and with no adaption to the local reality. It was also that they were short-termed and devised just for architects. Archaeological and historical research was disregarded or belittled. With time, they realized that the interventions had to be multidisciplinary. “Now is different”, Barrios said; “The research component in archaeological projects is more consistent, but we are still under the influence of foreign trends.”

In Peru, as in many other countries, the relationship between

puesta en valor of the cultural heritage and tourism is a symbiotic one. Over the last few decades, Peru has experienced a huge boost in tourism development, as cultural tourism has become a driving force for the Peruvian economy, as well as an instrument of State policy for projecting a certain image of the country abroad [

34,

35]. For Barrios, this widespread, often uncontrolled, development has taken a toll, both in the commodification of the Pre-Hispanic legacy as well as in its integrity and originality as defined in the charters.

“The consequence of tourist development for the projects of puesta en valor is that it demands new circuits, new places for visiting that require puesta en valor. Archaeologists are desperate about recovering new sites for tourism no matter how well or badly they do it. Planning is poor and short-termed, resulting in misguided projects. The technological process is negatively affected. The expectation of a rapid upgrading invites the use of modern materials and technologies that replace traditional ones in order to obtain greater consistency in less time.”

Yet, perhaps the main problem triggered by an indiscriminate

puesta en valor of Pre-Hispanic and colonial material legacy concerns the social domain. More often than not, these processes have been implemented at the expense of the local population living in or close to the sites, as Gibaja’s report made clear. The literature on Peru [

4,

36] documents cases of exclusion and displacement of villagers in the Sacred Valley when indigenous archaeological landscapes are patrimonialized and become ‘sites’ for scientific research and tourism consumption. Barrios expressed frustration when he acknowledged that the original idea in Ollantaytambo had been returning the site to their legitimate owners (the villagers), so that it could be a truly ‘living site’ by rehabilitating the old canals and terraces for the continuation of agricultural production. Instead, he thought that monumentalism had made Ollantaytambo a site for

gringo tourists, as well as a place for racial segregation. Moreover, the villagers did not economically benefit directly from the site, thus preventing their identification with their heritage. His words were eloquent:

“The dominant paradigm has been to create a monument for the tourist, dead places. Our original idea was to socially revitalize the park by allowing the villagers to use it and to work their fields within it, so that the tourist could see what their current life is like.”