1. Introduction

Sustainable waste management has emerged as one of the most critical environmental, technological, and economic challenges of the 21st century, with direct implications for food security, climate change mitigation, and the efficient use of natural resources. Among various organic waste streams, residues generated by fisheries and aquaculture represent a rapidly growing and particularly impactful fraction. Inefficient management of these residues leads to nutrient losses, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and aquatic ecosystem contamination, exacerbating eutrophication and water quality deterioration [

1,

2]. This situation highlights the urgent need for sustainable technological strategies capable of converting aquatic residues into high-value products under the principles of the circular and blue bioeconomy.

Over recent decades, the expansion of global fisheries and aquaculture has been driven by increasing population growth, rising protein demand, and technological advances in harvesting and processing [

3]. According to FAO [

4], total aquatic production reached 223.2 million tonnes (Mt) in 2022, of which 185.4 Mt were destined for direct human consumption, consolidating aquaculture as the main source of marine protein. However, between 30% and 70% of the processed fish mass becomes solid or liquid residues such as heads, scales, skin, viscera, and bones, which can represent up to 80% of the dry weight of the raw material [

5,

6]. These residues are rich in proteins (49–58%), lipids (7–19%), ashes (21–30%), and polysaccharides such as chitin (up to 21%), as well as collagen and polyunsaturated fatty acids of high biological value [

7,

8]. Despite this significant biochemical potential, a large fraction remains underutilized, leading to environmental burdens and economic losses.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies have quantified the environmental footprint of seafood processing industries, revealing substantial impact values: 9.66 kg CO

2−equivalent per kilogram of processed product, 0.079 kg SO

2−eq associated with acidification, 0.02 kg PO

43−-eq linked to eutrophication, and 0.17 kg 1,4-DCB-eq related to human toxicity [

9]. These findings highlight the importance of developing sustainable valorization pathways that aim both to minimize carbon intensity and to enable the recovery of valuable nutrients from biomass residues.

Conventional valorization pathways, including fishmeal and fish oil production, silage, or anaerobic digestion, remain limited in scalability and efficiency. These processes rely heavily on fresh raw materials, show low nutrient recovery yields, and often generate high-strength effluents [

2,

10]. In contrast, hydrothermal thermochemical technologies have emerged as promising alternatives to these conventional biological routes, as they can convert wet and heterogeneous biomass into energy-rich products without prior drying, thereby offering the potential to reduce overall energy demand and environmental impacts [

11].

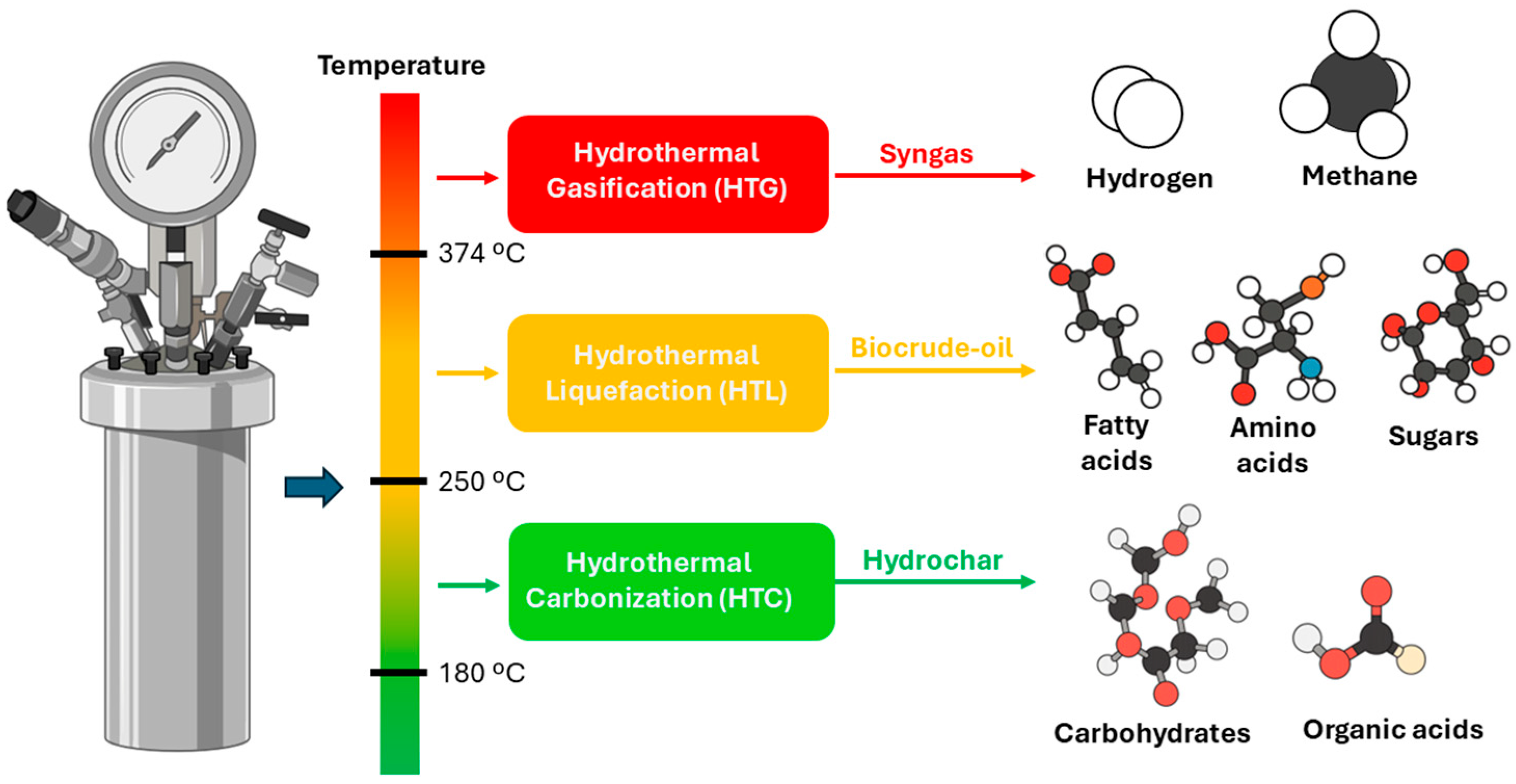

Among these, three major routes have gained relevance: Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC), Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL), and Hydrothermal Gasification (HTG). Each operates within a specific range of temperature and pressure, yielding distinct products and offering unique advantages for different biomass types [

12].

Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC) typically occurs between 180 and 250 °C under autogenous pressures (1–5 MPa) and residence times ranging from 0.5 to 24 h. Under these subcritical conditions, reactions of hydrolysis, dehydration, decarboxylation, and aromatization take place, producing a carbon-rich solid known as hydrochar, along with an aqueous phase containing dissolved organics and nutrients, and a minor gaseous phase mainly composed of CO

2 [

13]. Compared with dry thermochemical routes, such as pyrolysis, HTC offers lower energy consumption, higher process efficiency, and direct treatment of wet biomass. The resulting hydrochar exhibits tunable porosity, high thermal and chemical stability, and favorable adsorption capacity, making it applicable in energy, soil amendment, catalysis, and wastewater treatment [

14,

15].

Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) operates at 250–374 °C and pressures of 5–20 MPa. HTL promotes the depolymerization of macromolecules, particularly lipids and proteins, into an energy-dense liquid phase termed biocrude. This biocrude exhibits properties comparable to petroleum-derived crude oil and can be further upgraded to produce liquid fuels and valuable chemical intermediates [

16]. For lipid- and protein-rich feedstocks such as fish residues, HTL can achieve carbon conversion efficiencies above 60%, offering a feasible route for renewable fuel generation.

At supercritical conditions (>374 °C, >22 MPa), Hydrothermal Gasification (HTG) enables the complete conversion of wet biomass or hydrochar into a gaseous mixture primarily composed of H

2, CO, and CH

4. In these conditions, water acts simultaneously as solvent, reactant, and catalyst, enhancing reaction kinetics and mass transfer. HTG processes can achieve hydrogen yields up to 76.7 g H

2 per kilogram of biochar, with energy efficiencies exceeding 35% [

17,

18]. HTG therefore represents a direct, though moderately efficient, pathway for renewable hydrogen and synthetic gas production from wet organic residues.

Integrating HTC, HTL, and HTG within a single hydrothermal biorefinery provides a comprehensive multiproduct valorization approach. In this framework, HTC converts carbohydrates and proteins into hydrochar, HTL liquefies lipids and amino compounds into biocrude and HTG converts both hydrochar and aqueous residues into hydrogen-rich syngas [

19]. This sequential conversion scheme maximizes carbon recovery, enhances energy yield, and minimizes secondary waste generation, aligning with the principles of a low-carbon circular bioeconomy.

The performance of these processes can be further optimized by the incorporation of alkaline catalytic additives such as NaHCO

3, Na

2CO

3, K

2CO

3, and CaO. These catalysts enhance dehydration, decarboxylation, and reforming reactions, as well as promoting CO

2 capture and hydrogen generation. Among them, NaHCO

3 serves as an effective, low-cost, and pH-buffering catalyst that facilitates organic carbon conversion and nutrient migration into the aqueous phase [

20,

21]. Na

2CO

3 enhances deoxygenation and reduces char formation [

22], while K

2CO

3 improves ionic mobility and selectivity toward H

2 during HTG [

23]. CaO acts as an in situ CO

2 sorbent and stabilizes hydrochar by reducing aromatic condensation and polycyclic compound formation [

24,

25]. The synergistic combination of these alkaline catalysts increases process efficiency and accelerates carbon conversion, making them ideal for large-scale hydrothermal valorization of fishery wastes.

The integral valorization of fish residues through these hydrothermal catalytic routes is fully consistent with the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, particularly the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 7, 12, and 13. SDG 7 promotes affordable and clean energy, SDG 12 encourages responsible production and consumption, and SDG 13 focuses on climate action [

26,

27]. By converting high-moisture fishery by-products into valuable materials and renewable fuels, hydrothermal biorefineries contribute directly to the transition toward carbon-neutral and resource-efficient production systems [

26,

27]. By converting high-moisture fishery by-products into valuable materials and renewable fuels, hydrothermal biorefineries contribute directly to the transition toward carbon-neutral and resource-efficient production systems.

In this context, the present study addresses an existing knowledge gap by evaluating the catalytic hydrothermal carbonization of fish residues using NaHCO3 as an additive, followed by gasification of the resulting hydrochars. This multiproduct approach offers valuable insight into carbon conversion, hydrogen generation, and nutrient recovery, paving the way for sustainable, circular, and low-carbon production systems applicable to the blue bioeconomy sector.

Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the three principal hydrothermal conversion routes (HTC, HTL, and HTG), their operating temperature ranges, and corresponding product outputs. As temperature increases, the transformation progresses from solid hydrochar formation (180–250 °C), through biocrude-oil generation (250–374 °C), to syngas production rich in H

2 and CH

4 (>374 °C). This thermodynamic gradient illustrates the flexibility and scalability of hydrothermal technologies for the valorization of aquatic residues within a circular, low-carbon framework.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental design was developed to ensure reproducibility and facilitate comparison with the existing literature. It covered the complete workflow, from raw material handling to the characterization of all products derived from hydrothermal carbonization (HTC). The methodological approach was structured to minimize external variability, enabling the establishment of clear and reproducible correlations between operating conditions and the physicochemical properties of the resulting fractions.

2.1. Raw Material

Fish residues were provided by Extrepronatour S.L. (Badajoz, Spain). The material was delivered in sealed 10 L containers, subdivided into 500 g units, vacuum-packed, and immediately frozen at −20 °C. This protocol ensured the preservation of intrinsic properties and prevented enzymatic degradation or microbial activity prior to processing, which is critical for biomass rich in proteins and lipids. The morphological appearance of the raw material is shown in

Figure 2.

In the final run, sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, purity of ≥99%, Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) was added as a catalytic agent. This compound was selected due to its low cost, wide availability, and favorable safety profile compared with other alkaline additives, while still being effective in promoting dehydration and decarboxylation reactions under hydrothermal conditions. Upon decomposition, NaHCO3 releases CO2 and forms Na2CO3 and NaOH, thereby modifying the reaction medium and facilitating the redistribution of carbon and nutrients between solid, liquid and gaseous phases.

2.2. Experimental Conditions

Experiments were carried out in a stainless-steel batch reactor (Parr 4848, Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA), specifically designed for high-pressure and high-temperature hydrothermal operations. The reactor was equipped with automated sensors for continuous monitoring of temperature and pressure, ensuring precise control of the reaction parameters throughout the experiments (

Figure 3). The mass of biomass inputs and all resulting product fractions was determined using an analytical balance (Cobos analytical balance, Cobos Precision S.L., Barcelona, Spain; ±0.1 mg precision), guaranteeing high accuracy in yield calculations.

Six experimental runs were performed, each with a constant reaction time of 3 h. This residence time was selected because approximately 3 h is sufficient for the main hydrothermal carbonization reactions (dehydration, decarboxylation, and condensation) to reach completion without excessive degradation of organic matter. Previous studies have shown that extending the reaction time beyond 3–4 h provides minimal improvements in hydrochar yield or carbon content but increases energy demand and operating costs [

28,

29]. Therefore, a reaction time of 3 h was chosen as an optimal compromise, ensuring complete carbonization kinetics and reproducibility under controlled laboratory conditions.

Runs one to five were designed to isolate the effect of temperature while maintaining a constant biomass-to-water ratio of 1:1 (

w/

w). This ratio was selected to provide sufficient liquid for uniform heat transfer and an adequate hydrothermal medium, while avoiding unnecessary dilution that would reduce energy efficiency. Ratios between 1:1 and 1:3 have been reported as optimal for high-moisture or protein-rich biomasses such as fish residues, since they prevent excessive hydrolysis and organic matter loss while maintaining sufficient water for reaction stability [

30,

31].

Run six represented a high-severity condition with reduced biomass load, relative excess water, NaHCO3 addition, and elevated temperature, simulating conditions closer to those expected in catalytic or intensified HTC scenarios.

All experiments were performed in duplicate, and the results from each replicate showed excellent agreement (differences below 3%). The high consistency observed between runs confirms the robustness and stability of the experimental procedure. Consequently, the data presented are considered fully representative of the hydrothermal carbonization behavior under the investigated conditions.

The operational parameters applied in the six experimental runs are summarized in

Table 1.

Runs one to five provided a systematic evaluation of temperature effects under standard conditions, while run six enabled assessing the combined influence of increased thermal severity and medium alkalinity.

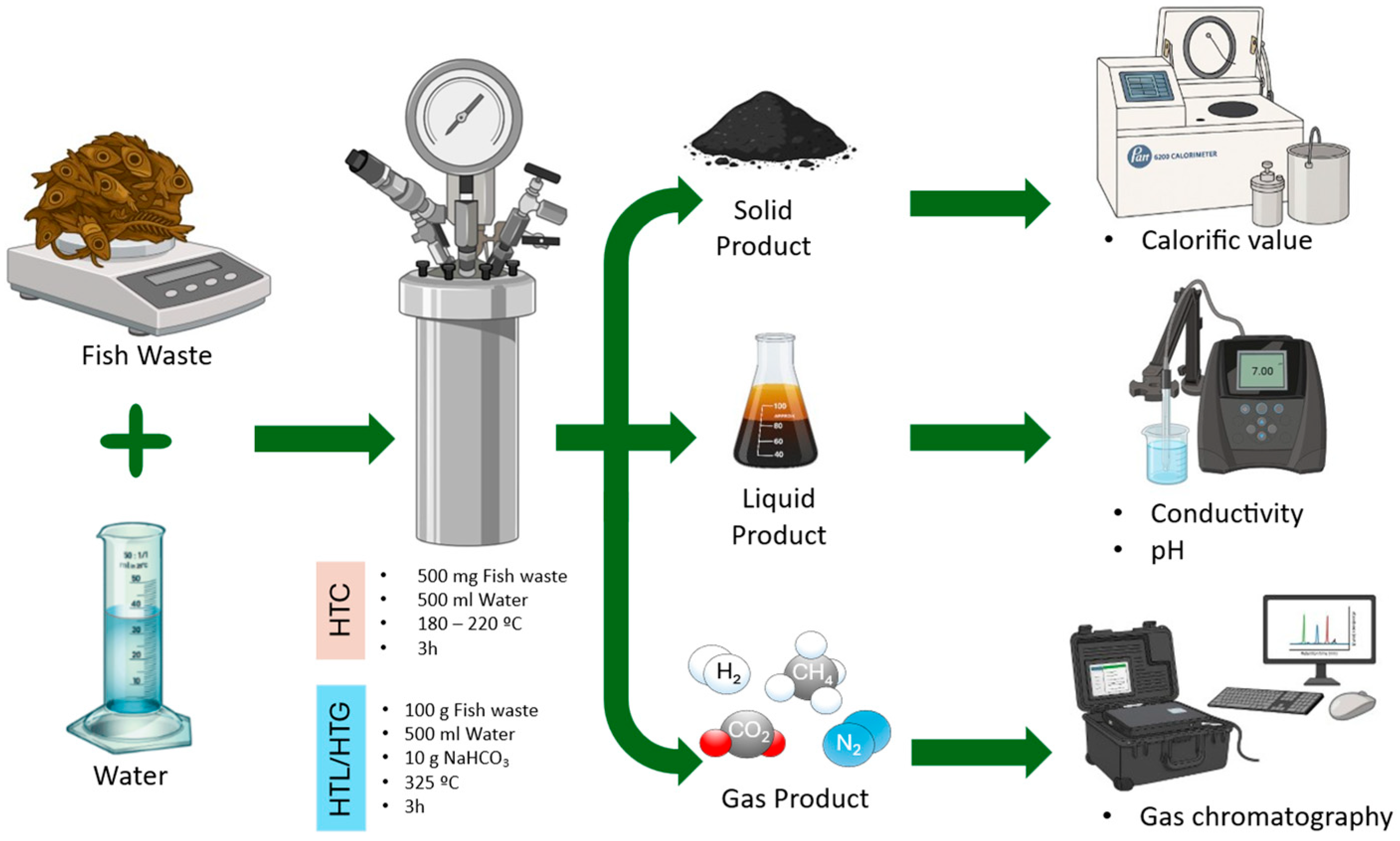

2.3. Product Separation

At the end of each run, products were separated into solid, liquid, and gaseous fractions to facilitate independent characterization. Hydrochar was recovered by filtration, dried at 105 °C until constant weight, and stored in airtight containers to prevent moisture uptake. The liquid fraction was diluted 1:20 with distilled water immediately after recovery; this step was essential to stabilize the aqueous phase and avoid secondary polymerization reactions that could alter its composition. The gaseous fraction was collected directly from the reactor headspace and analyzed immediately after depressurization to prevent compositional drift due to leakage or adsorption phenomena.

2.4. Product Characterization

The efficiency of hydrochar production was expressed as solid yield (

SY), calculated according to Equation (1):

where

mf represents the mass of dried hydrochar (g) and

mi the initial mass of raw biomass (g). This metric was selected as a primary indicator of HTC conversion performance.

The energy content of the produced hydrochars was determined through the higher heating value (HHV) using a bomb calorimeter (Parr 1351, Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA).

The liquid fraction was analyzed for pH using a digital pH meter (Crison, Barcelona, Spain) and for electrical conductivity using a digital conductimeter (Crison, Barcelona, Spain). These parameters provided an overview of the ionic content and acid–base balance, which are essential for assessing downstream applications such as nutrient recovery and biofertilizer production.

The gaseous fraction was analyzed by gas chromatography (Agilent 990, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), allowing for precise quantification of the major gas components, including H2, CO2, CH4, CO, and N2. This analytical approach ensured an accurate evaluation of gas composition under different operating conditions.

The analytical methods employed are summarized in

Table 2.

The integration of these analyses provided a comprehensive overview of the process, from biomass conversion efficiency to the energetic and chemical characterization of the liquid and gaseous fractions (

Figure 4). This methodological approach ensures comparability with previous literature and establishes a basis for future optimizations aimed at the integral valorization of fishery residues.

3. Results

This section presents the results of hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) of fish residues, organized by product fraction, hydrochar, aqueous phase, and gas, as well as by the reactivity of selected hydrochars under air gasification. The catalytic test with sodium bicarbonate is also highlighted, as it produced distinctive conditions for hydrogen enrichment.

3.1. Hydrochar Yield and Energy Potential

Hydrochars represent the solid fraction of HTC and their energy content is crucial to evaluating their potential as renewable fuels. As shown in

Table 3, HHVs ranged from approximately 14 to 26 MJ/kg, with marked differences depending on feed fraction and operating severity.

In several experiments, distinct solid portions of the hydrochar, such as the carbon-rich and bone-rich fractions, were analyzed, allowing direct comparison of their respective energy contents. For instance, samples produced at 180 °C and 190 °C showed markedly different HHV, with higher energy content in those sub-fractions that already displayed a charcoal-like morphology (particularly fraction c). However, fraction separation was not performed in this study, as it would represent an additional cost in an industrial-scale process. Consequently, samples prepared at 200, 210 and 220 °C correspond to the total solid fraction recovered after HTC without separation.

Except for the carbon-rich fraction (HC-c), HHV was relatively low compared with those typically reported for lignocellulosic biomass, which can be attributed to the high mineral content of the feedstock. Nevertheless, a slight increase in HHV with temperature was observed, consistent with progressive dehydration and carbon enrichment at higher HTC severities.

Comparable results were reported by Kannan et al. [

32], who performed HTC of fish residues under similar temperature conditions (190–210 °C) combined with microwave treatment, obtaining HHV between 17 and 25 MJ kg

−1. These authors also examined the evolution of O/C and H/C ratios using the Van Krevelen diagram, observing that (unlike lignocellulosic biomasses) the H/C ratio remained nearly constant as severity increased, which they attributed to the predominance of decarboxylation over dehydration.

Figure 5 reproduces the Van Krevelen diagram, illustrating the tendency of fish residues to maintain a constant H/C ratio with increasing temperature. This interpretation aligns with the observations from the present study, which also suggest the predominance of decarboxylation mechanisms during HTC of fish residues.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that hydrochars preserve significant energy content and compositional diversity, making them promising solid fuels or carbon-rich precursors for further upgrading.

3.2. Aqueous Fraction

The hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) process applied to fish residues promoted extensive decomposition of the biomass, resulting in the generation of a predominant liquid fraction and a smaller amount of solid hydrochar.

Table 4 summarizes the experimental results for the mass of the aqueous fraction obtained in each run. In all cases, the recovered liquid mass was high, generally exceeding 900 g, indicating a substantial degree of conversion of the feedstock under subcritical conditions.

With the exception of one run at 200 °C, which was affected by a minor pressure loss in the reactor, the liquid yields remained high and consistent, with an average recovery of approximately 90% of the initial biomass mass. This stability reflects the effectiveness of the hydrothermal environment in promoting physical and chemical transformations that favor the formation of a dominant liquid phase, even under moderate reaction conditions [

33,

34].

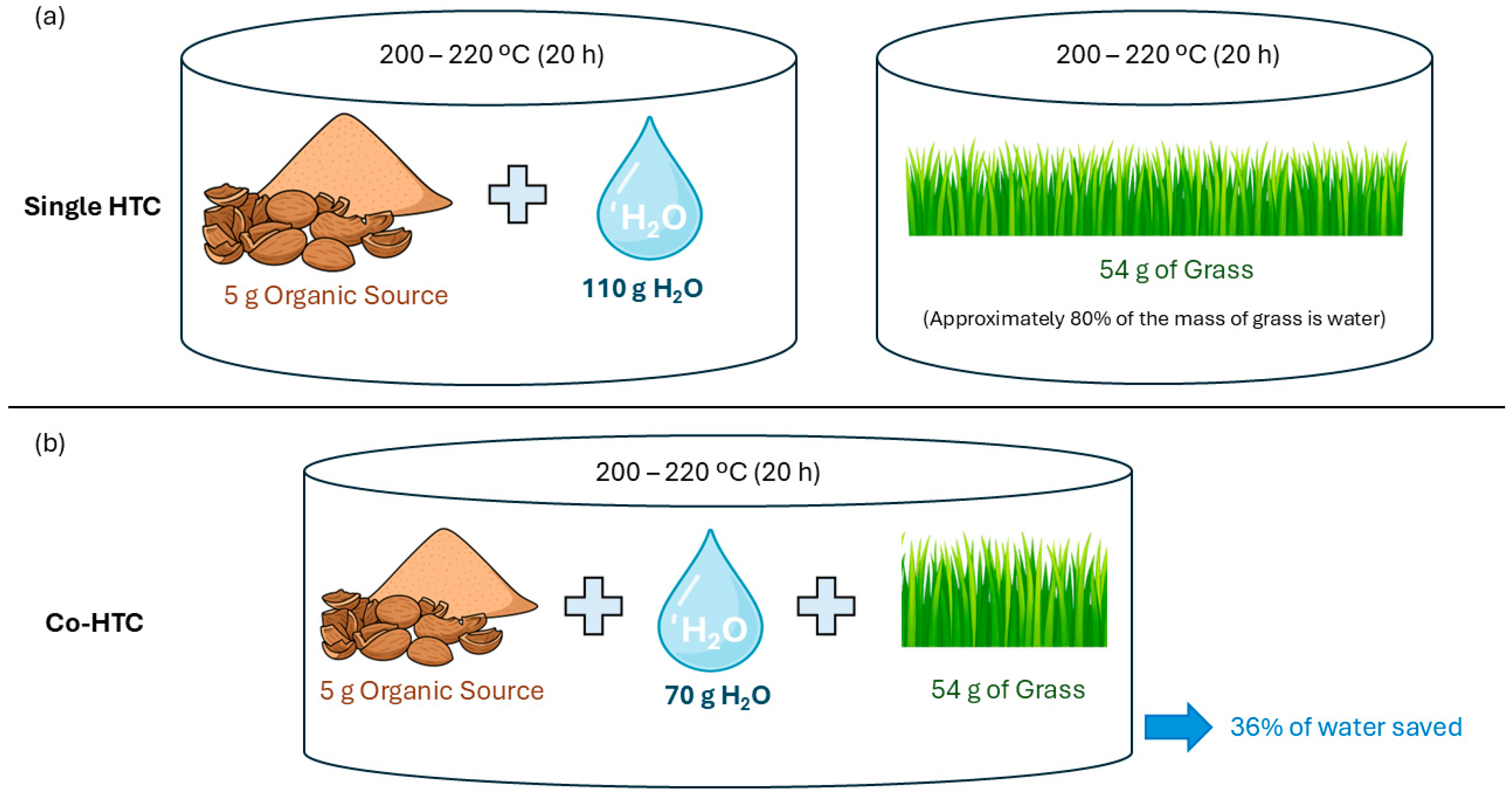

To contextualize these experimental findings within the broader framework of water management in hydrothermal systems,

Figure 6 is presented below. This schematic, developed by the GAIRBER research group [

35], conceptually illustrates different HTC configurations based on the source and utilization of water within the system.

In

Figure 6a, two independent configurations are shown: (i) HTC performed with externally added water and (ii) HTC applied to wet biomass without additional water input, relying on intrinsic moisture.

Figure 6b represents the co-hydrothermal carbonization (Co-HTC) process, where dry and wet biomasses are treated simultaneously in a single reactor. This configuration enables more efficient use of the available water and potentially reduces overall water consumption.

Although the present study exclusively employed a mixture of biomass and externally added water, the high liquid yields obtained demonstrate a strong interaction between the organic matrix and the hydrothermal medium under subcritical conditions. These findings highlight the efficiency of HTC for processing wet fish residues and support its potential as a low-water-demand conversion route within sustainable waste valorization strategies.

3.3. Gas Fraction

The gas composition generated during the hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) process, as shown in

Table 5, provides important insights into the dominant decomposition pathways of the biomass.

In the non-catalytic experiments, CO

2 was the predominant gaseous product, accompanied by a gradual decrease in N

2 and small amounts of CO and CH

4. The concentration of H

2 remained almost undetectable within the investigated temperature range, confirming that decarboxylation was the main gas-forming mechanism under these conditions. This behavior agrees with previous HTC studies, where CO

2 evolution has been linked to the removal of carboxylic and phenolic groups from the biomass matrix [

36].

In contrast, the catalytic experiment at 325 °C showed a moderate increase in H

2 concentration, reaching about 30 vol.%. This result indicates that NaHCO

3 promoted partial activation of the water gas shift (WGS) reaction, enhancing hydrogen formation in situ. Although the increase in H

2 content was moderate, it clearly demonstrates a catalytic effect compared with the non-catalytic baseline. Similar H

2 concentrations, typically between 25 and 35 vol.%, have been reported in the literature, but generally at higher temperatures (350 to 425 °C) when alkaline or hydrotalcite-type catalysts are used [

36,

37,

38].

Comparable results have been reported by other authors, but usually under more severe conditions. Zeng and Shimizu reported up to 35 vol.% H

2 at temperatures above 400 °C [

36], while Lee et al. obtained similar yields using Cu-Mg-Al hydrotalcite-derived catalysts between 350 and 400 °C [

37]. Likewise, Khandelwal et al. achieved around 30 vol.% H

2 during catalytic hydrothermal gasification with alkaline carbonates, but only above 375 °C [

38]. Achieving a similar H

2 yield at 325 °C in the present study, therefore, highlights the relatively high catalytic efficiency of NaHCO

3 under milder hydrothermal conditions.

Overall, the results show that NaHCO3 acts as a moderate but effective catalytic promoter, enhancing hydrogen formation at lower temperatures without significantly changing the overall gas composition. This consistent improvement supports the role of alkaline media in facilitating the WGS reaction and provides additional experimental evidence of the influence of NaHCO3 on gas distribution under hydrothermal conditions.

3.4. Hydrochar Gasification

The gasification of hydrochars was conducted under oxidizing conditions using air at 800 °C and 900 °C, with the objective of comparing the composition of the resulting gases with that obtained during hydrothermal treatments (HTC and HTL). This comparison underscores the intrinsic differences between the reducing aqueous environment typical of hydrothermal processes and the high-temperature oxidative atmosphere characteristic of gasification [

39,

40,

41].

Table 6 summarizes the total moles of the main gaseous species formed under these conditions. Hydrochars produced at 200 °C were gasified at both 800 °C and 900 °C, each analyzed in duplicate due to the higher hydrochar yield obtained at this HTC temperature. In contrast, the hydrochar prepared at 220 °C was gasified only once at 800 °C, as its lower solid yield limited the available sample amount. The reported values correspond to independent experimental runs conducted under identical conditions, ensuring the consistency and reproducibility of the results.

Increasing the temperature markedly modified the gas composition, promoting the formation of H

2 and CO while progressively reducing CO

2 concentrations. Light hydrocarbons (CH

4, C

2H

4, C

2H

6, and traces of C

2H

2) were also detected, originating from thermal cracking and secondary reforming reactions within the residual carbonaceous matrix. This behavior reflects the high thermal reactivity of the material and the predominance of conversion pathways that favor the generation of reducing gases [

42,

43].

At 900 °C, the product gas exhibited H

2/CO ratios between 2 and 3, values suitable for Fischer–Tropsch (FT) and biomass-to-liquids (BTL) synthesis. These ratios are consistent with those reported in previous studies on high-temperature biomass gasification aimed at the production of industrial-grade syngas [

44,

45,

46,

47].

The inorganic composition of the hydrochar likely influenced the conversion reactions. Previous research has shown that alkali and alkaline-earth metals such as Ca, Na, and K can act as catalytic promoters during gasification, reducing the activation energy and enhancing CO

2 reforming and reduction reactions [

41,

43,

48]. However, this potential catalytic effect was not verified within the scope of the present study be further investigated in future work.

Compared to hydrothermal treatments, gasification exhibited similar trends in both gas composition and carbon conversion. During HTC, CO

2 formation dominated due to decarboxylation, whereas HTL favored higher H

2 yields through aqueous-phase reforming. Under gasification conditions, the reaction equilibrium shifted toward reducing gas mixtures dominated by H

2 and CO, reflecting the combined influence of temperature, reaction atmosphere, and the potential catalytic contribution of inorganic species to syngas quality [

40,

49].

Overall, these findings confirm that hydrochars derived from fish residues via hydrothermal carbonization exhibit high reactivity and efficient conversion, making them promising precursors for syngas production. The results provide a sound experimental basis for the mechanistic and redox equilibrium analyses discussed in

Section 4.

4. Discussion

The hydrothermal carbonization of fish residues under subcritical conditions produced solids with moderate energy potential and clear structural heterogeneity. This heterogeneity reflects the complex composition of the feedstock, where organic and mineral fractions coexist and influence the degree of carbon concentration. Comparable observations have been reported for marine and mineral-containing biomasses, where inorganic domains hinder uniform solid formation and affect carbonization efficiency [

50]. The slight increase in apparent carbonization with temperature suggests progressive dehydration and rearrangement of organic matter, consistent with the thermal behavior expected in hydrothermal carbonization processes [

51].

A high recovery of the liquid phase was observed during the HTC process, remaining stable across the tested temperature range. This behavior indicates significant solubilization of organic matter, suggesting an efficient interaction between the feedstock and the hydrothermal medium. Although the composition of this phase was not analyzed, the high liquid recovery aligns with findings from protein-rich biomasses, where hydrolysis and partial depolymerization generate soluble low-molecular-weight intermediates. Such aqueous fractions have been described as potentially valuable for nutrient recovery or further conversion in circular biorefinery schemes [

52,

53].

The transition toward higher severity conditions resulted in a reduction of the solid fraction and a clear change in the gas phase. The addition of NaHCO

3 coincided with an increase in hydrogen proportion, indicating a modification of the reaction environment under alkaline conditions. Although the specific pathways were not determined, this outcome aligns with trends observed in other alkaline-assisted hydrothermal systems, where carbonate additives alter solubility equilibria and the distribution of gaseous products [

54]. The lower heating value of the solid under catalytic conditions suggests that the additive promoted higher conversion rather than an increase in solid energy density.

Gasification of the hydrochars confirmed their good reactivity and the generation of reducing gas mixtures. The variation in hydrogen and carbon monoxide with temperature indicates a favorable shift toward more reactive gaseous species. This observation is consistent with general gasification behavior reported for hydrothermally derived solids from nitrogen- and ash-rich biomasses [

55]. While the catalytic influence of mineral matter was not examined in this work, its potential role cannot be ruled out and could be explored in future studies.

Overall, the combination of hydrothermal carbonization, high-severity treatment, and gasification provided a coherent picture of carbon redistribution across the solid and gaseous fractions. The results demonstrate that moderate hydrothermal processes can effectively convert fish residues into reactive solids and gas streams of energetic interest, supporting the potential of hydrothermal conversion as a sustainable valorization route within a circular bioeconomy framework [

56].

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the technical feasibility of hydrothermal conversion as an integrated route for the valorization of fish-processing residues, enabling the production of energy-relevant products from a wet and heterogeneous biomass.

Under subcritical HTC conditions, fish residues were efficiently converted into reactive hydrochars with moderate heating values, suitable for further thermochemical upgrading. The addition of NaHCO3 modified the reaction environment, promoting higher hydrogen proportions in the gaseous phase without the use of metallic catalysts, confirming its potential as an accessible and low-impact alkaline additive.

A high recovery of the liquid phase was also observed, indicating strong interaction between the organic matrix and the hydrothermal medium. Although its composition was not analyzed in this work, its abundance suggests promising opportunities for future valorization through nutrient recovery or secondary conversion pathways within circular biorefinery frameworks.

The gasification of the produced hydrochars confirmed their high reactivity and the formation of H2- and CO-rich syngas mixtures, suitable for energy recovery and synthesis applications. Furthermore, the process’s capability to efficiently treat high-moisture biomass supports its integration with low-moisture feedstocks in co-hydrothermal systems, enhancing overall carbon efficiency and process sustainability.

Collectively, these results position hydrothermal technologies as versatile, efficient, and sustainable platforms for marine residue valorization, contributing to the development of circular bioeconomy strategies and the transition toward low-carbon production systems.