Liquid Addition Techniques to Enhance Methane Biotrickling Filters at Dairy Barn Concentrations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biotrickling Filter Design and Gas Delivery

2.2. Aerosol Production

2.3. Traditional and Aerosol Biotrickling Filter Setup

2.4. Inlet Methane Concentration and Liquid Addition Rate Experiments

2.5. Microbial Community Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

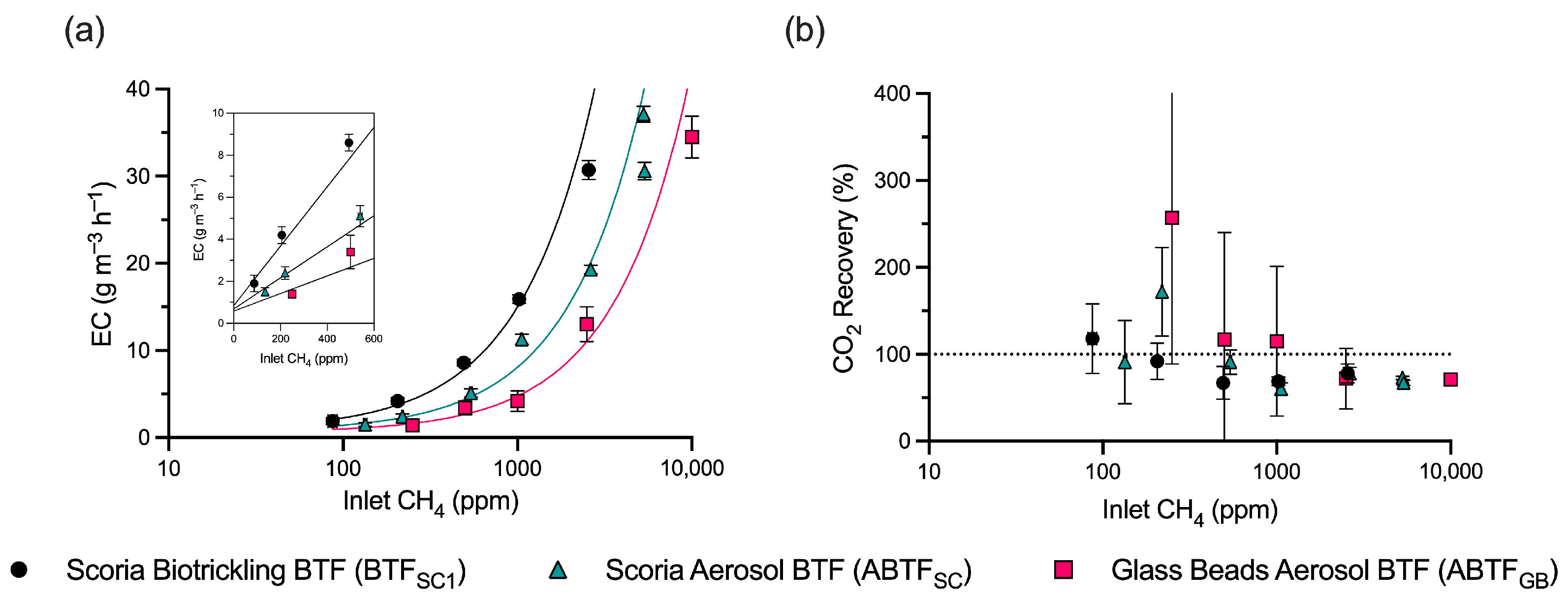

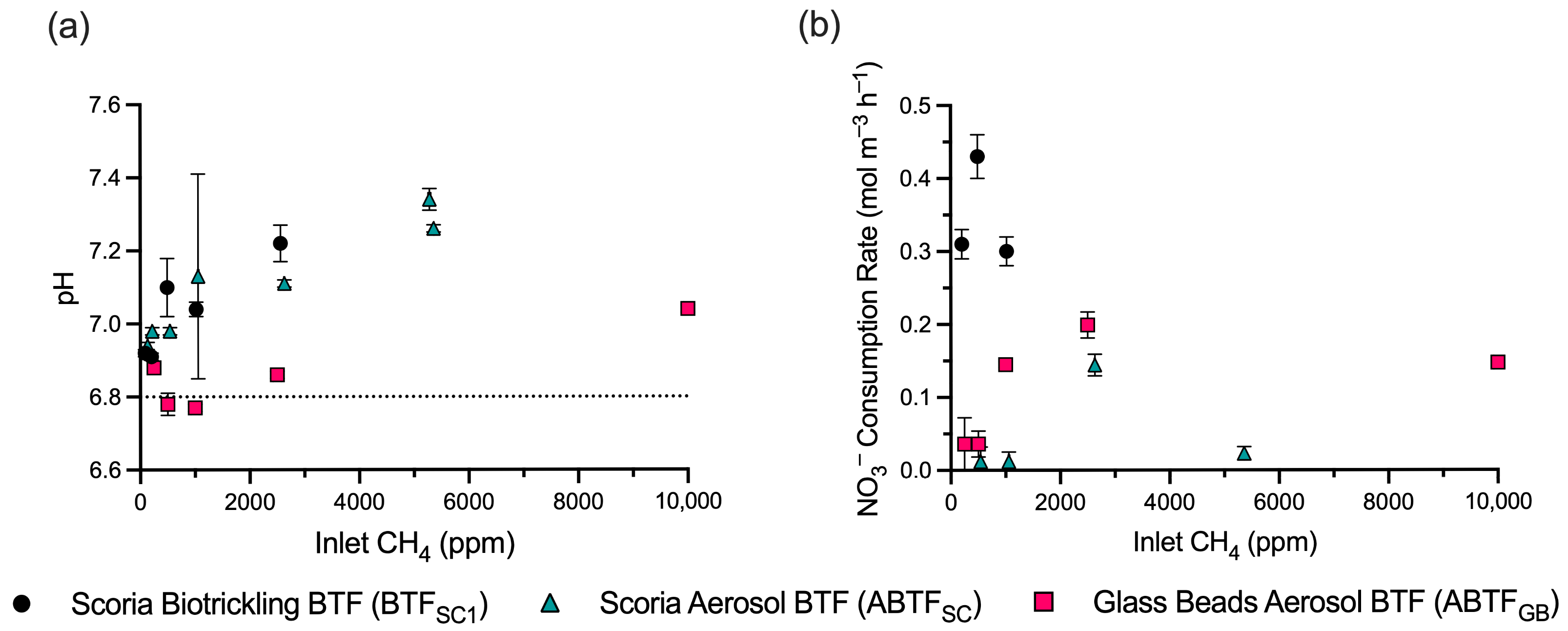

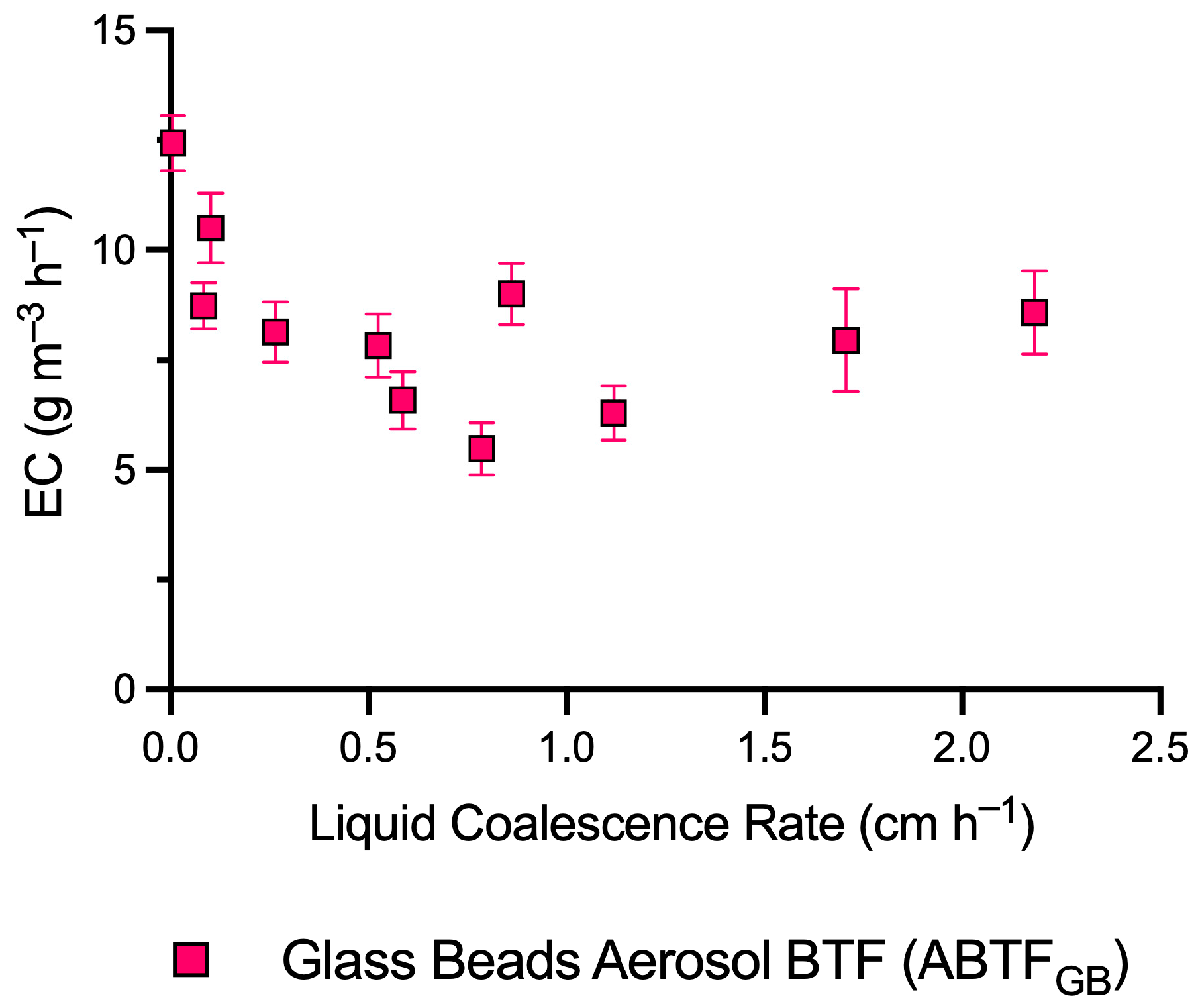

3.1. Performance of the Glass Bead Aerosol Biotrickling Filter (ABTFGB)

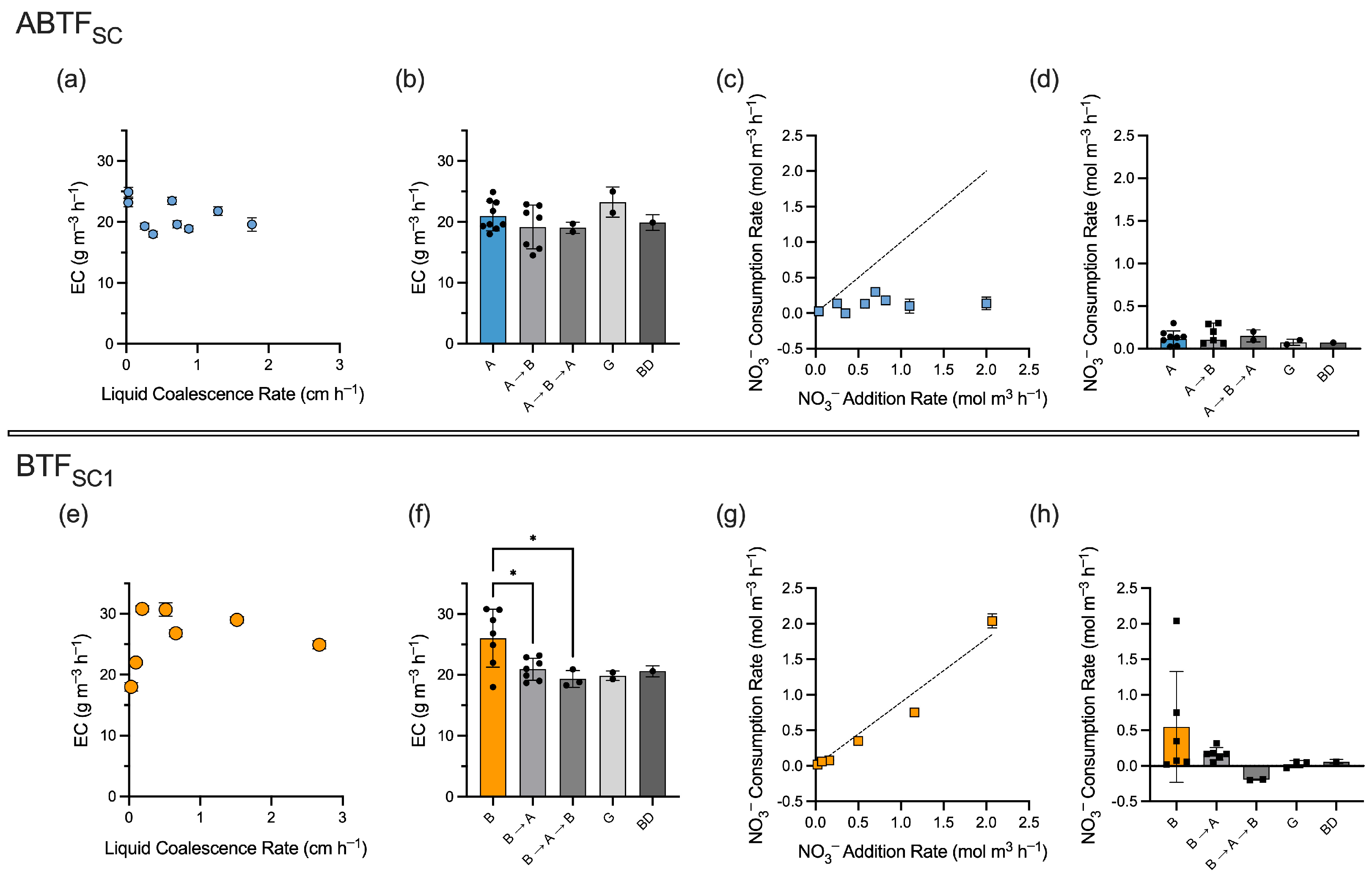

3.2. Performance of the Aerosol Biotrickling Filter (ABTFSC) and Biotrickling Filter (BTFSC1)

3.3. Comparison of Packing Materials and Liquid Addition Mechanisms

3.4. The Impact of Liquid Addition Rates on CH4 Removal

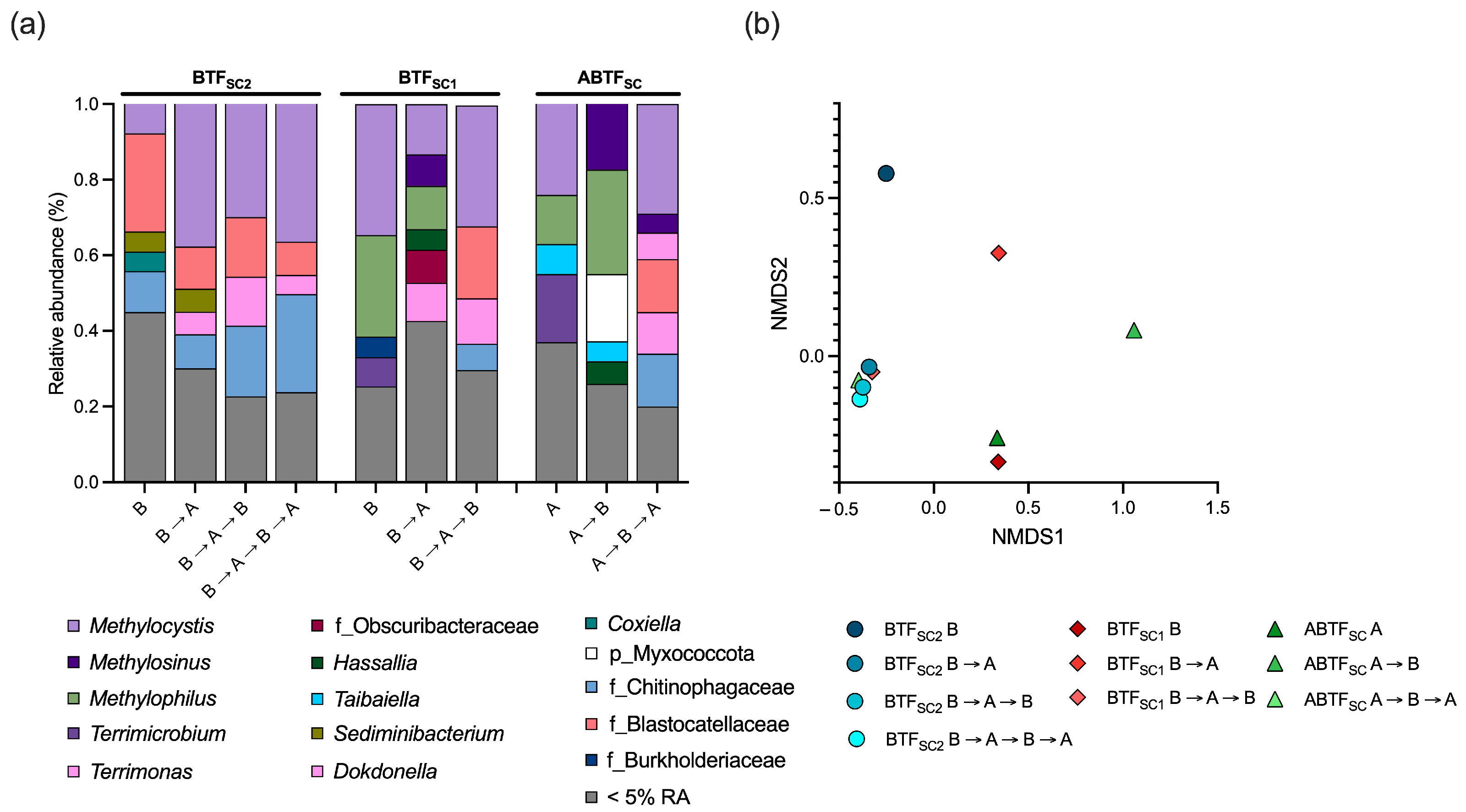

3.5. Microbial Community Structures in BTFs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A-NZ | Aotearoa New Zealand |

| ABTF | Aerosol-fed biotrickling filter |

| ABTFGB | Glass-bead aerosol-fed biotrickling filter |

| ABTFSC | Scoria aerosol-fed biotrickling filter |

| Ar-NMS | Aerosol nitrate mineral salts growth medium |

| ASV | Amplicon sequence variant |

| BTF | Biotrickling filter |

| BTFSC1 | Scoria biotrickling filter reactor 1 |

| BTFSC2 | Scoria biotrickling filter reactor 2 (replicate) |

| EBRT | Empty bed residence time |

| EC | Elimination capacity |

| EPS | Extracellular polymeric substances |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| RE | Removal efficiency |

| IL | Inlet load |

References

- Guerrero-Cruz, S.; Vaksmaa, A.; Horn, M.A.; Niemann, H.; Pijuan, M.; Ho, A. Methanotrophs: Discoveries, Environmental Relevance, and a Perspective on Current and Future Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 678057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, A. The Contribution of Methane Emissions from New Zealand Livestock to Global Warming; New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC): Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Human Security: Building Resilience to Climate Threats (Human Security and Climate Change Policy Brief); United Nations Trust Fund for Human Security, Ed.; United Nations: New York City, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stats, N.Z. Greenhouse Gas Emissions (Industry and Household): December 2023 Quarter. 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/greenhouse-gas-emissions-industry-and-household-december-2023-quarter/ (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Ministry for the Environment. New Zealand’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990–2019; New Zealand Government; Ministry for the Environment: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021.

- AgMatters. Reduce Methane Emissions; New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger, A.; Clark, H.; Abercrombie, R.; Aspin, M.; Ettema, P.; Harris, M.; Hoggard, A.; Newman, M.; Sneath, G. Future Options to Reduce Biological GHG Emissions on-Farm: Critical Assumptions and National-Scale Impact; New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsman, R.; Sauer, F.; Jackson, H.; Wolynetz, M. Methane and Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Dairy Cows in Full Lactation Monitored over a Six-Month Period. J. Dairy Sci. 1995, 78, 2760–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor. Methane Production by Ruminant Animals: Current and Future Technologies; New Zealand Government: Wellington, New Zealand, 2024.

- Buddle, B.M.; Denis, M.; Attwood, G.T.; Altermann, E.; Janssen, P.H.; Ronimus, R.S.; Pinares-Patiño, C.S.; Muetzel, S.; Neil Wedlock, D. Strategies to reduce methane emissions from farmed ruminants grazing on pasture. Vet. J. 2011, 188, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcon, W.P.; Naylor, R.L.; Shankar, N.D. Rethinking Global Food Demand for 2050. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2022, 48, 921–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.L.; Davison, T.M.; Box, I. Methane Emissions from Ruminants in Australia: Mitigation Potential and Applicability of Mitigation Strategies. Animals 2021, 11, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baca-González, V.; Asensio-Calavia, P.; González-Acosta, S.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Morales de la Nuez, A. Are Vaccines the Solution for Methane Emissions from Ruminants? A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2020, 8, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subharat, S.; Dairu, S.; Zheng, T.; Buddle, B.M.; Kaneko, K.; Hook, S.; Janssen, P.H.; Wedlock, D.N. Vaccination of Sheep with a Methanogen Protein Provides Insight into Levels of Antibody in Saliva Needed to Target Ruminal Methanogens. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruminant Biotech. 2025. Available online: https://ruminantbiotech.com/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Wallace, R.J.; Sasson, G.; Garnsworthy, P.C.; Tapio, I.; Gregson, E.; Bani, P.; Huhtanen, P.; Bayat, A.R.; Strozzi, F.; Biscarini, F.; et al. A heritable subset of the core rumen microbiome dictates dairy cow productivity and emissions. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannan, O. Capturing Bulls’ Breath Could Help Breed Lower-Methane Cows; Stuff: Morrinsville, New Zealand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kinley, R.D.; Martinez-Fernandez, G.; Matthews, M.K.; de Nys, R.; Magnusson, M.; Tomkins, N.W. Mitigating the carbon footprint and improving productivity of ruminant livestock agriculture using a red seaweed. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, B.M.; Venegas, M.; Kinley, R.D.; de Nys, R.; Duarte, T.L.; Yang, X.; Kebreab, E. Red seaweed (Asparagopsis taxiformis) supplementation reduces enteric methane by over 80 percent in beef steers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subharat, S.; Shu, D.; Zheng, T.; Buddle, B.M.; Janssen, P.H.; Luo, D.; Wedlock, D.N. Vaccination of cattle with a methanogen protein produces specific antibodies in the saliva which are stable in the rumen. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2015, 164, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lide, D. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (Vol. Internet Version); CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.; Yang, L.; Ning, J.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, F. Catalytic combustion of low-concentration methane over transition metal oxides supported on open cell foams. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, A.; Galama, P.; Spoelstra, S.F.; Wiering, C.J.; Groot Koerkamp, P.W.G. Invited review: Combined mitigation of methane and ammonia emissions from dairy barns through barn design, ventilation and air treatment systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 6565–6586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesário, M.T.; Beverloo, W.A.; Tramper, J.; Beeftink, H.H. Enhancement of gas-liquid mass transfer rate of apolar pollutants in the biological waste gas treatment by a dispersed organic solvent. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 1997, 21, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdowsi, M.; Avalos Ramirez, A.; Jones, J.P.; Heitz, M. Elimination of mass transfer and kinetic limited organic pollutants in biofilters: A review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 119, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, S.; Astefanei, A.; Corthals, G.L.; Bonn, D. Size distributions of droplets produced by ultrasonic nebulizers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vela, R.; Gostomski, P.A. Design and Performance of a Toluene-Degrading Differential Biotrickling Filter as an Alternative Research Tool to Column Reactors. J. Environ. Eng. 2021, 147, 04020159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Deshusses, M. Determination of mass transfer coefficients for packing materials used in biofilters and biotrickling filters for air pollution control. 1. Experimental results. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yue, P.; Huang, L.; Zhao, M.; Kang, X.; Liu, X. Styrene removal with an acidic biofilter with four packing materials: Performance and fungal bioaerosol emissions. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedysh, S.; Dunfield, P. Cultivation of methanotrophs. In Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology Protocols; Springer Protocol Handbooks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunfield, P.; Yuryev, A.; Senin, P.; Smirnova, A.; Stott, M.; Hou, S.; Ly, B.; Saw, J.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, Y.; et al. Methane oxidation by an extremely acidophilic bacterium of the phylum Verrucomicrobia. Nature 2007, 450, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griess, P. Bemerkungen zu der Abhandlung der HH. Weselsky und Benedikt „Ueber einige Azoverbindungen”. Berichte Der Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1879, 12, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidin, D.; Gostomski, P.A.; Marshall, A.T.; Carere, C.R. Bio-electrochemical denitrification—The impact of cathode potential, inoculum source and nitrate loading rate. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 79, 108923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Robledo, E.; Corzo, A.; Papaspyrou, S. A fast and direct spectrophotometric method for the sequential determination of nitrate and nitrite at low concentrations in small volumes. Mar. Chem. 2014, 162, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, K.M.; Espey, M.G.; Wink, D.A. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide 2001, 5, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigley, K.; Egbadon, E.; Carere, C.; Weaver, L.; Baronian, K.; Burbery, L.; Dupont, P.; Bury, S.; Gostomski, P. RNA stable isotope probing and high-throughput sequencing to identify active microbial community members in a methane-driven denitrifying biofilm. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 132, 1526–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbadon, E.O.; Wigley, K.; Nwoba, S.T.; Carere, C.R.; Weaver, L.; Baronian, K.; Burbery, L.; Gostomski, P.A. Microaerobic methane-driven denitrification in a biotrickle bed—Investigating the active microbial biofilm community composition using RNA-stable isotope probing. Chemosphere 2024, 346, 140528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwoba, S.; Carere, C.; Wigley, K.; Baronian, K.; Weaver, L.; Gostomski, P. Using RNA-Stable isotope probing to investigate methane oxidation metabolites and active microbial communities in methane oxidation coupled to denitrification. Chemosphere 2024, 357, 140528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.R.; Sambrook, J. Precipitation of DNA with Ethanol. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2016, 2016, pdb-prot093377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingett, S.W.; Andrews, S. FastQ Screen: A tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Research 2018, 7, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.P.; Peterson, D.A.; Biggs, P.J. SolexaQA: At-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: Highresolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.R.; Wang, Q.; Fish, J.A.; Chai, B.; McGarrell, D.M.; Sun, Y.; Brown, C.T.; Porras-Alfaro, A.; Kuske, C.R.; Tiedje, J.M. Ribosomal Database Project: Data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D633–D642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, M.; Ramirez, A.A.; Buelna, G.; Heitz, M. Biofiltration of methane at low concentrations representative of the piggery industry—Influence of the methane and nitrogen concentrations. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 168, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, A.H.; Branion, R.M.R.; Lau, A.K. Biofiltration: A promising and cost-effective control technology for Odors, VOCs and air toxics. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A Environ. Sci. Eng. Toxicol. 1997, 32, 2027–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, L.; Gunawan, C.; Thomas, T.; Smith, A.; Scott, J.; Rosche, B. Coal-Packed Methane Biofilter for Mitigation of Green House Gas Emissions from Coal Mine Ventilation Air. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiema, J.; Bibeau, L.; Lavoie, J.; Brzezinski, R.; Vigneux, J.; Heitz, M. Biofiltration of methane: An experimental study. Chem. Eng. J. 2005, 113, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiema, J.; Girard, M.; Brzezinski, R.; Heitz, M. Biofiltration of methane using an inorganic filter bed: Influence of inlet load and nitrogen concentration. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2009, 36, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedrizzi, F.; Cabana, H.; Ndanga, É.; Cabral, A. Biofiltration of methane from cow barns: Effects of climatic conditions and packing bed media acclimatization. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordoloi, A.; Gostomski, P. Fate of degraded pollutants in waste gas biofiltration: An overview of carbon end-points. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, H.; Hettiaratchi, J.; Achari, G.; Dunfield, P. Biofiltration of methane. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 268, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, J.M.; Lebrero, R.; Quijano, G.; Pérez, R.; Figueroa-González, I.; García-Encina, P.A.; Muñoz, R. Methane abatement in a gas-recycling biotrickling filter: Evaluating innovative operational strategies to overcome mass transfer limitations. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 253, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdowsi, M.; Veillette, M.; Ramirez, A.A.; Jones, J.P.; Heitz, M. Performance Evaluation of a Methane Biofilter Under Steady State, Transient State and Starvation Conditions. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016, 227, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, C.-H.; Ryu, C.-R.; Sung, K. Biofiltration for Reducing Methane Emissions from Modern Sanitary Landfills at the Low Methane Generation Stage. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2009, 196, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Paul, D.; Jain, R.K. Biofilms: Implications in bioremediation. Trends Microbiol. 2006, 14, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabiri, B.; Ferdowsi, M.; Buelna, G.; Jones, J.; Heitz, M. Methane biofiltration under different strategies of nutrient solution addition. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiema, J.; Brzezinski, R.; Heitz, M. Influence of phosphorus, potassium, and copper on methane biofiltration performance. A paper submitted to the Journal of Environmental Engineering and Science. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2010, 37, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Porca, E.; Collins, G.; Pérez, R.; Rodríguez-Alija, A.; Muñoz, R.; Quijano, G. Biogasbased denitrification in a biotrickling filter: Influence of nitrate concentration and hydrogen sulfide. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melse, R.W.; Hol, J.M.G. Biofiltration of exhaust air from animal houses: Evaluation of removal efficiencies and practical experiences with biobeds at three field sites. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 159, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Understanding Global Warming Potentials. 2021. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/understanding-global-warming-potentials (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Sun, M.-T.; Zhao, Y.-Z.; Yang, Z.-M.; Shi, X.-S.; Wang, L.; Dai, M.; Wang, F.; Guo, R.-B. Methane elimination using biofiltration packed with fly ash ceramsite as support material. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-M.; Yang, J.; Fan, X.-L.; Fu, S.-F.; Sun, M.-T.; Guo, R.-B. Elimination of methane in exhaust gas from biogas upgrading process by immobilized methane-oxidizing bacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 231, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.H.; Sapre, A.V. Trickle-bed reactor flow simulation. AIChE J. 1991, 37, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Nigam, K.D.P.; Roy, S. Bed structure and its impact on liquid distribution in a trickle bed reactor. AIChE J. 2023, 69, e17649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danila, V.; Zagorskis, A.; Januševičius, T. Effects of Water Content and Irrigation of Packing Materials on the Performance of Biofilters and Biotrickling Filters: A Review. Processes 2022, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasi, N.; Rossi, E.; Pecorini, I.; Iannelli, R. Methane Oxidation Efficiency in Biofiltration Systems with Different Moisture Content Treating Diluted Landfill Gas. Energies 2020, 13, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wei, W.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Peng, L.; Wang, D.; Ni, B.-J. Denitrifying biofilm processes for wastewater treatment: Developments and perspectives. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 40–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.; Conrad, R. Effect of CH4 concentrations and soil conditions on the induction of CH4 oxidation activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1995, 27, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, É. Impact of the treatment of NH(3) emissions from pig farms on greenhouse gas emissions. Quantitative assessment from the literature data. New Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asserghine, A.; Baby, A.; N’Diaye, J.; Romo, A.I.B.; Das, S.; Litts, C.A.; Jain, P.K.; Rodríguez-López, J. Dissolved Oxygen Redox as the Source of Hydrogen Peroxide and Hydroxyl Radical in Sonicated Emulsive Water Microdroplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 11851–11858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatoo, M.A.; Mishra, H. Busting the myth of spontaneous formation of H2O2 at the air–water interface: Contributions of the liquid–solid interface and dissolved oxygen exposed. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 3093–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A., Jr.; Musskopf, N.H.; Liu, X.; Yang, Z.; Petry, J.; Zhang, P.; Thoroddsen, S.; Im, H.; Mishra, H. On the formation of hydrogen peroxide in water microdroplets. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 2574–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Walker, K.L.; Han, H.S.; Kang, J.; Prinz, F.B.; Waymouth, R.M.; Nam, H.G.; Zare, R.N. Spontaneous generation of hydrogen peroxide from aqueous microdroplets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 19294–19298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebert, J.; Stralis-Pavese, N.; Alawi, M.; Bodrossy, L. Analysis of methanotrophic communities in landfill biofilters using diagnostic microarray. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Yang, A.; Yao, H. Morphological and spatial heterogeneity of microbial communities in pilot-scale autotrophic integrated fixed-film activated sludge system treating coal to ethylene glycol wastewater. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 927650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Jeong, S.; Cho, K. Functional rigidity of a methane biofilter during the temporal microbial succession. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 3275–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, J.; Rovira, R.; Álvarez-Hornos, F.; Fortuny, M.; Lafuente, J.; Gamisans, X.; Gabriel, D. Bacterial community analysis of a gas-phase biotrickling filter for biogas mimics desulfurization through the rRNA approach. Chemosphere 2010, 80, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Xing, H.; Li, J. Performance and fungal diversity of bio-trickling filters packed with composite media of polydimethylsiloxane and foam ceramics for hydrophobic VOC removal. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chistoserdova, L.; Lapidus, A.; Han, C.; Goodwin, L.; Saunders, L.; Brettin, T.; Tapia, R.; Gilna, P.; Lucas, S.; Richardson, P.; et al. Genome of Methylobacillus flagellatus, molecular basis for obligate methylotrophy, and polyphyletic origin of methylotrophy. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 4020–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Tao, Y.; Gao, P.; Xu, Y.; Xing, P. Comparative genomics revealing insights into niche separation of the genus Methylophilus. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, F.; Wang, L.; Ju, X.; Wu, W.; Chen, Y. Molecular characterization of a microbial consortium involved in methane oxidation coupled to denitrification under micro-aerobic conditions. Microb. Biotechnol. 2014, 7, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, M.; Tan, G.; Sun, F.; Wang, C.; Wu, W.; Lee, P. Microbiology and potential applications of aerobic methane oxidation coupled to denitrification (AME-D) process: A review. Water Res. 2016, 90, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baideme, M.; Long, C.; Chandran, K. Enrichment of a denitratating microbial community through kinetic limitation. Environ. Int. 2022, 161, 107113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetz, S.; Horn, M. Burkholderiaceae are key acetate assimilators during complete denitrification in acidic cryoturbated peat circles of the Arctic Tundra. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 628269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, L.; Wang, Y.; Shen, X.; Li, S. Taibaiella smilacinae gen. nov., sp nov., an endophytic member of the family Chitinophagaceae isolated from the stem of Smilacina japonica, and emended description of Flavihumibacter petaseus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 3769–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Li, R.; Li, F.; Jin, L.; Wu, H.; Cheng, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Structural characteristics and diversity of the rhizosphere bacterial communities of wild Fritillaria przewalskii Maxim. in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1070815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, S.; Cho, N.; Arun, A.; Chen, W. Terrimonas aquatica sp. nov., isolated from a freshwater spring. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 2705–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, B.; Tang, X.; Liu, S. Metagenomic insights into functional traits variation and coupling effects on the anammox community during reactor start-up. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 687, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pryor, A.M.; Gostomski, P.A.; Carere, C.R. Liquid Addition Techniques to Enhance Methane Biotrickling Filters at Dairy Barn Concentrations. Clean Technol. 2026, 8, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010003

Pryor AM, Gostomski PA, Carere CR. Liquid Addition Techniques to Enhance Methane Biotrickling Filters at Dairy Barn Concentrations. Clean Technologies. 2026; 8(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010003

Chicago/Turabian StylePryor, Anna M., Peter A. Gostomski, and Carlo R. Carere. 2026. "Liquid Addition Techniques to Enhance Methane Biotrickling Filters at Dairy Barn Concentrations" Clean Technologies 8, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010003

APA StylePryor, A. M., Gostomski, P. A., & Carere, C. R. (2026). Liquid Addition Techniques to Enhance Methane Biotrickling Filters at Dairy Barn Concentrations. Clean Technologies, 8(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010003