Abstract

The application of dynamic vibration absorbers (DVAs) is a countermeasure to suppress vibrations induced by railway traffic. A key advantage of the DVA application is that it does not require any changes to the path of vibration propagation or the receiver of vibration. A review of the literature reveals the necessity of deriving the optimum properties of DVA to mitigate railway vibrations. To this end, the optimum DVA properties were investigated through the development of a two-dimensional finite element model of the track-tunnel-soil system. The model was validated using the results of a field test. A parametric study was made to obtain the optimum properties of DVA for different soils surrounding the tunnel. The results of the model analysis indicate that the DVA has better vibration reduction for metro tunnels built in soft soils as compared to those surrounded by medium and stiff soils. Also, the results disclose that the DVA reduces vibration radiated on the ground surface when the DVA natural frequency is tuned to a low frequency. Using the results of the parametric study, graphs are suggested to select the optimum properties of the DVA as a function of the soil around the tunnel.

1. Introduction

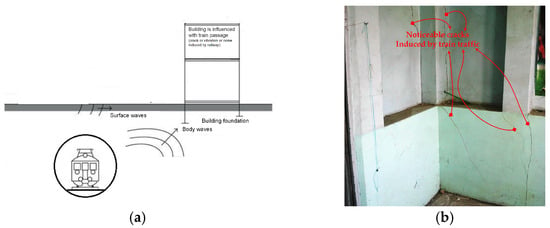

In recent decades, underground railway networks (subway and metro transportation systems) have been extended significantly. Also, the development of metro lines has solved heavy traffic and reduced greenhouse gas emission challenges [1]. However, ground-borne vibrations induced by underground railways are unavoidable challenges for urban rail transit (as shown in Figure 1a). In fact, the vibrations induced by the underground railway are propagated within the soil surrounding the tunnel and transmitted to buildings in the vicinity of the railway. The vibrations cause discomfort and annoyance to people as shown in Figure 1b [2]. Vibrations with low frequency content, specifically those of less than 20 (Hz), have adverse influences on buildings and are, importantly, undesirable to people living adjacent to the railway [3,4]. Residents of nearby buildings perceive the vibrations due to the oscillation of building elements in the frequency range of 1 to 80 (Hz) [5,6]. Also, the oscillation leads to structure-borne noise in the frequency range of 16 to 250 (Hz) [5,6].

Figure 1.

Challenges made by urban rail transit. (a) Schematic image of wave propagation due to metro-induced vibration, and (b) apparent cracks on wall plaster of residential building in the vicinity of metro tunnel (adapted from [2]).

There are several countermeasures to dissipate ground-borne vibration propagated from underground railway tunnels [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. That is, the application of resilient layers such as rail pads, under sleeper pads, ballast mat, and under-slab elastomeric layer is a method to suppress vibrations in the source. The use of unfilled or in-filled trenches or a wave barrier is an approach to mitigate vibrations within the path. Finally, the application of a base isolator or resilient layer under foundation is a solution to control vibration in the receiver of vibrations. The application of a dynamic vibration absorber (DVA) is an influential countermeasure to limit/suppress vibrations of structures subjected to dynamic loads [15,16,17,18,19]. The DVA plays as a secondary oscillating system that is connected to a main system called the host structure [20,21]. Typically, DVAs are used to moderate the response of the host system in a specific frequency range [22,23].

The survey of the literature reveals that there are some studies on the application of DVAs in the vibration attenuation of railway vehicles and tracks. That is, to control vehicle vibration, DVA was used near the unsprung masses in the rolling stock [19]. Moreover, DVAs with negative stiffness were installed on rail in a ballasted track to attenuate the vibration propagation and noise [17]. Also, the application of DVAs in a floating slab track for limiting track vibration was studied [18,24,25]. Moreover, Noori et al. [16,26] studied the application of DVA in limiting underground railway-induced vibration. That is, DVAs were used in a double-deck circular railway tunnel. The Pipe-in-Pipe (PiP) model, which is a full-space model, was employed to study DVA vibration suppression. The PiP model cannot consider vibration transmitted to the ground surface. Also, the soil surrounding the tunnel was only considered as a homogeneous medium, and multilayered soil was not considered [26,27]. The survey of the literature elucidates that there is insufficient research on the study of optimum DVA for the mitigation of ground surface vibrations induced by the railway tunnel. In fact, there is a need to tune DVA properties as a function of soil condition (i.e., vibration path) around the metro tunnel. To fill this research gap, the optimum properties of DVA for different soils around the metro tunnel were obtained. To this end, parametric studies were conducted using the development of a two-dimensional (2D) finite element (FE) model of a railway tunnel surrounded by soil. The model was validated through measurement results derived from a field test. Design graphs were obtained to acquire the mass, stiffness, and damping values for the optimum DVA as a function of the soil properties. The solution suggested in this research is a practical method to attenuate train-induced vibrations, especially the installation of DVAs in the metro tunnel which does not make any change in the track and tunnel structure, and train traffic is not interrupted.

2. Numerical Modeling

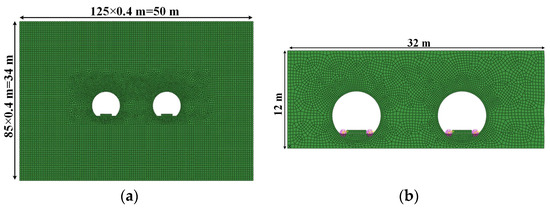

A 2D FE model of an underground railway cross-section, including the railway slab track, tunnel, and soil around the tunnel (a track-tunnel-soil system) was developed using Abaqus FE software (Abaqus 2018, Dassault Systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France). The model is shown in Figure 2. The results from the model were verified with measurements from a field test. After confirming the model’s accuracy, parametric studies were performed on the DVA properties to find the best features of the DVA. The following describes the details of the model development.

Figure 2.

A 2D FE model of track-tunnel-soil system for wave propagation: (a) General view of the FE model; (b) position of DVA (in pink) near the slab track.

2.1. Finite Element Model

A cross-section of a metro twin tunnel and surrounding soils was simulated. Both tunnels have circular shapes. Plane strain elements were used to model the slab track, tunnel lining, and soil. These elements have four nodes with two translational degrees of freedom for each node. The model size was chosen to allow free wave propagation and ensure results were not influenced by boundary conditions or the size of the model. Sensitivity analysis was performed on the vertical and horizontal dimensions. The model’s dimensions are shown in Figure 2: a width of 50 m, a depth of 34 m, a tunnel inner-radius of 3 m, a tunnel-lining thickness of 0.3 m, and a center-to-center tunnel distance of 13 m. The tunnel centers are 18 m below the ground surface. The slab track’s thickness and width are 0.4 m and 2.4 m, respectively. To simulate the interaction between the tunnels and soil, the tunnel nodes were tied to the soil nodes at the contact edge.

Since only small strains occur due to railway vibrations, the material behavior of the concrete slab track, tunnel lining, and soil was assumed to be linear elastic [27,28]. To prevent wave reflection, energy-absorbing boundary conditions were set up at the boundaries [29,30]. Normal and tangential spring-dashpot elements were used at all nodes on the boundaries to absorb waves. That is, the boundary conditions ensure that compression and shear incident waves are not reflected into the interior domain and are efficiently absorbed by dashpot elements. The vibration propagation problem in the soil around the tunnel was solved using an implicit time integration method (Newmark method) in Abaqus. Implicit methods are unconditionally stable [31], but the time step must be smaller than the inverse of the highest frequency of interest. For ground-borne vibrations, frequencies from 1 to 80–100 (Hz) are influential [5,32,33,34], so the time step was selected to be less than 0.01 s. Residents of buildings near the railway perceive vibrations in this frequency band [5,32,34,35]. To excite the track, the impulse load was applied on the rail seat on the slab, creating a load with constant amplitude within 1 to 100 (Hz).

2.2. Field Test for Validation of Model Results

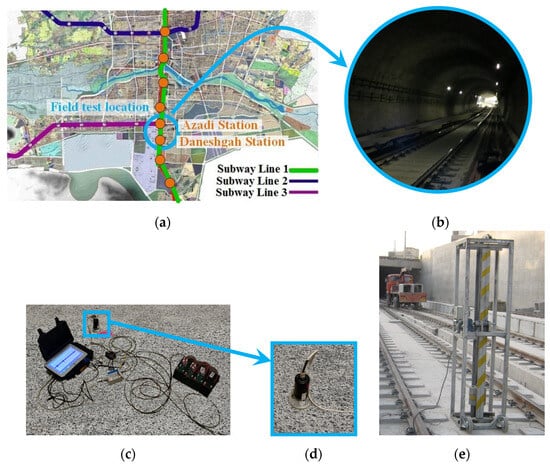

To verify the accuracy of the model, its results were compared with field test measurements. The field test was conducted in the Isfahan metro network. That is, the measurement was made in Line 1 between Daneshgah and Azadi stations, as shown in Figure 3. In this railway section, there is a twin tunnel, each with a single railway slab track. The track is tangent and has no longitudinal slope. It consists of S49 rails attached every 0.6 (m) to a reinforced concrete slab. At the test location, the ground surface is 18 (m) above the center of the tunnel. The tunnel has an inside diameter of 6.0 (m), with a lining thickness of 0.3 (m). The elastic moduli of the tunnel lining, slab track, and soil are 32.5 (GPa), 35 (GPa), and 150 (MPa), respectively. The densities of tunnel lining, slab track, and soil are 2500, 2500, and 2000 (kg/m3), respectively [36]. These parameters were used as the input data for the model.

Figure 3.

In situ test setup: (a) Map of Isfahan metro network; (b) general view of metro line in the field test; (c) equipment for vibration measurement (Data acquisition system and uniaxial velocimeter); (d) uniaxial velocimeter used for vibration measurement on ground surface; and (e) impact hammer device (before installation in metro tunnel).

For vibration measurement, uniaxial velocimeters (that have the commercial title of MTSS-1001 geophone, (R-sensors, Moscow region, Russia) were placed on the ground surface at several points, as shown in Figure 3c. These sensors measure maximum speeds of ±30 (mm/s) within a frequency range of 1–300 (Hz) and can sense low-amplitude vibrations. The Geo-Arm-D24 data acquisition system, with a sampling rate of 200 (Hz), recorded the ground vibrations (Figure 3a).

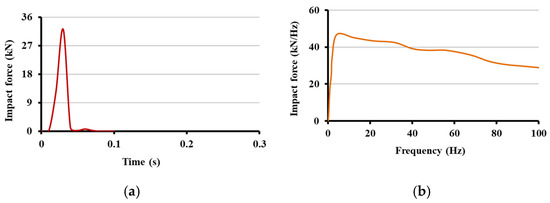

In the field test, ground vibrations due to an impulse from an impact hammer were measured. The hammer, a falling weight device, generated an impulse with a maximum load of 32 (kN), producing measurable vibrations. The impact load was recorded by a load cell installed on the hammer. As shown in Figure 4, the impact load was almost constant across 1 to 100 (Hz). The time history of the impact load was imported into the model as an excitation.

Figure 4.

The impulse load derived from the in situ test: (a) the impact load in the time domain; and (b) the impact load in the frequency domain.

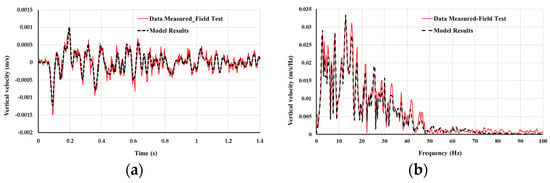

To allow vibration waves to propagate within the soil in the frequency range of 1 to 100 (Hz), the soil element size around the tunnel was selected to be small enough. In fact, the maximum soil element size was chosen based on the minimum wavelength of vibration, which is related to the shear wave velocity of the soil and the highest frequency of interest. That is, the maximum soil element size was chosen to be less than one-fourth to one-eighth of λmin of soil [28]. To find the best mesh size, a sensitivity analysis was performed. The soil mesh size was varied considering λmin and fmax criteria, and the velocity response on the ground surface was derived from the analysis. In fact, the soil mesh size varied from 20 (cm) to 50 (cm). By investigating the results obtained from models with various meshes, it was derived that a mesh size of 40 (cm) gives good convergence. To verify the model results, the vertical velocity of the ground surface at 5 (m) from the tunnel’s centerline was measured due to the impact load. The comparison was made between model results and the measurements at the receiver point, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Results obtained from the field test and those derived from the model: (a) Vibration response in the time domain; and (b) vibration response in the frequency domain.

It should be noted that for the dynamic analysis, a time step of 0.0025 s was used. This time step corresponds to a sampling frequency of 400 (Hz). So, the model results can possess a frequency content of up to 100 (Hz). As presented in Figure 5, there is a good agreement between the model and field test results, with differences of up to 6%, which is considered acceptable for this study. The discrepancies between the results of field measurement and numerical analysis arose from uncertainties in the material properties. Some of the differences also appeared because of simplifications made in the simulation of boundary conditions.

3. Parametric Analyses

In this section, the effect of DVAs on reducing the vibration energy propagated upwards from the metro tunnel was evaluated. To this end, the kinetic energy of multiple points on the ground surface located at different distances from the axis of the metro tunnel was obtained. Kinetic energy (representative of vibration energy) is derived using Equation (1) as follows [37]:

In this equation, V and , respectively, are the volume and velocity of the element. Parametric analyses of the model were used to derive the optimum characteristics (including mass, stiffness, and damping ratio) of a DVA that can efficiently moderate kinetic energy. To this end, kinetic energy on the ground surface was examined while the properties of DVA were changed. Generally, DVA is simulated as a single degree of freedom (SDOF) [23]. In this study, DVA was simulated as a SDOF that was installed on the track foundation adjacent to the slab track, as illustrated in Figure 2b. Properties of the slab and tunnel were selected to be the same as those in the field test. Excitation and boundary conditions in the model that had DVA were the same as those in the validated model. The properties of soil play a significant role in the ground-borne vibration induced by the metro. Various soil profiles around the tunnel were taken into account. That is, stiff, medium, and soft soil surrounding the metro tunnel were considered, as presented in Table 1. The soil properties were adapted from the codes of practice [38] to consider a wide range of soils in practice. In parametric studies, the characteristics of DVA (i.e., mass, stiffness, and damping value) were varied for each soil type. The optimum DVA is the one that attenuates metro-induced vibration (i.e., kinetic energy) the most.

Table 1.

Properties of soil neighboring the tunnel.

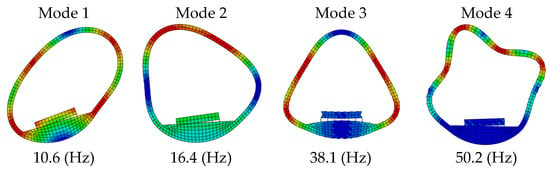

In accordance with design methods available in the literature [21,23], to achieve efficient performance of TMD or DVA, the natural frequency of DVA should be selected in harmony with the natural frequencies of the dominant modes of host (primary) structure. The natural frequency (fnd) of DVA is derived based on SDOF behavior. That is, , in which kd and md stand for stiffness and mass of DVA. In this study, eigenvalue analysis of the slab track-tunnel system was performed to derive the natural frequencies of the host system. In Figure 6, the natural frequencies and mode shapes of the slab track-tunnel system are shown.

Figure 6.

Natural frequencies and mode shapes of the slab track-tunnel system.

In accordance with the natural frequencies of the primary system shown in Figure 6, the natural frequency of DVA was changed from 1 (Hz) to 50 (Hz). In practice, the ratio of DVA mass to the mass of the host structure was selected in the range of 1% to 10% [21,23]. To begin parametric studies, light-mass DVAs (i.e., mass ratios of 0.01 and 0.05) were considered. The vibration of a point on the ground surface near the tunnel built in soft soil was investigated. The time increment in the implicit time integration method was set to 0.0025 (s), which is the same as the time increment considered in the validated model.

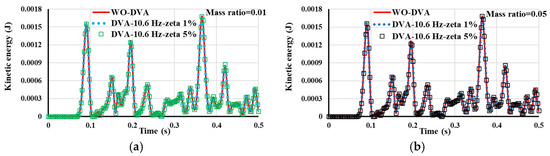

The natural frequency of DVA was tuned to be the same as the natural frequency of the track-tunnel system in the first mode of vibration (i.e., 10.6 (Hz)). In Figure 7a,b, the time history curves of kinetic energy for the point on the ground surface at 4 (m) from the tunnel axis are illustrated. DVAs with damping ratios of 0.01 and 0.05 were separately analyzed. Considering Figure 7a,b, kinetic energy is not influenced by DVA, and there is no significant change in the energy when light-mass DVA was installed near the track. Also, similar results (i.e., no significant changes) were derived when kinetic energy results were obtained for points located at the other distances from the tunnel axis.

Figure 7.

Time history of kinetic energy for the point at 4 (m) from the tunnel surrounded with soft soil: (a) Mass ratio of DVA equals 0.01; and (b) Mass ratio of DVA equals 0.05.

To further study the impact of light-mass DVA on ground-borne vibration, DVAs with different dynamic properties were simulated. That is, DVAs were tuned to have a natural frequency the same as the natural frequency of the slab-tunnel system for the second, third, and fourth modes of vibration. Damping ratios of 0.01 and 0.05 were considered. The results of analyses elucidate that DVAs with low mass do not have influential effects on vibration deterioration and cannot efficiently suppress ground-borne vibration. As shown in Figure 7a,b, an increase in the damping ratio of DVAs did not result in improvement of DVA effectiveness.

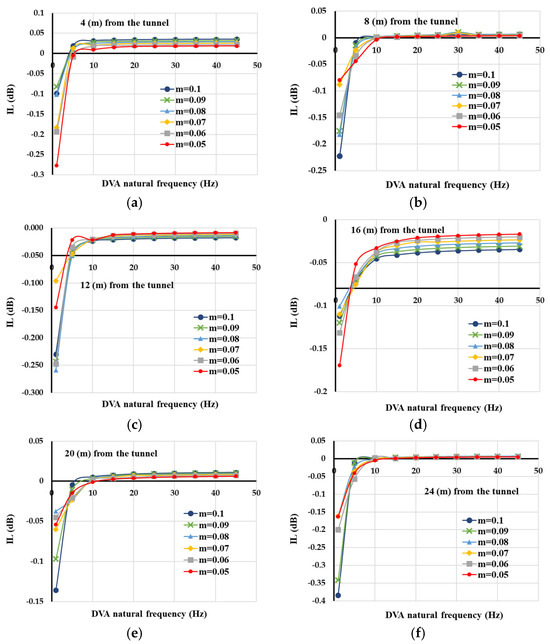

Because light-mass DVA has a negligible effect on vibration mitigation, the mass ratio of DVA gradually increased from 0.05 to 0.1 while the damping ratio of DVA was considered to be 0.01. The DVA natural frequency was also adjusted to closely match the slab-tunnel system’s natural frequencies and operate over a broad frequency band (i.e., from 1 (Hz) to 50 (Hz)). The results of the parametric studies are presented in Figure 8a–f.

Figure 8.

Insertion loss against the natural frequency of DVA when the tunnel is surrounded with soft soil: (a) Receiver point at 4 (m) from tunnel axis; (b) receiver point at 8 (m) from tunnel axis; (c) receiver point at 12 (m) from tunnel axis; (d) receiver point at 16 (m) from tunnel axis; (e) receiver point at 20 (m) from tunnel axis; and (f) receiver point at 24 (m) from tunnel axis.

To better show vibration suppression provided with DVA, the insertion loss index was derived. According to the literature [39], the insertion loss is a common index that represents changes in the mean vibrational energy. The insertion loss (IL) was derived using Equation (2):

In Equation (2), and are the root mean square (RMS) of the kinetic energy for a certain point when the track is equipped with DVA and when there is no DVA, respectively.

As presented in Figure 8a–f, insertion loss was significantly influenced by changes in the natural frequency of DVA and distance from the source of vibration. Generally, the most efficient condition was achieved when the DVA natural frequency was set to 1 (Hz), regardless of the distance of the receiver point from the tunnel and the DVA mass ratio. As the natural frequency of DVA increases more than 1 (Hz), DVA performance significantly deteriorates. In fact, except for the results obtained for a point at 16 (m) from the tunnel, when the DVA natural frequency is higher than 5 (Hz), the insertion loss was approximately unchanged. In other words, vibration mitigation was not influenced by DVA natural frequency and mass ratio. For the receiver point at 16 (m) from the tunnel, vibration suppression was slightly augmented with an increase in DVA natural frequency and mass ratio. To further investigate the influence of DVA properties on insertion loss, DVA mass ratios were gradually increased from 0.1 to 0.15, and parametric investigations were made on DVA characteristics. Results of parametric studies are illustrated in Figure 9a–f.

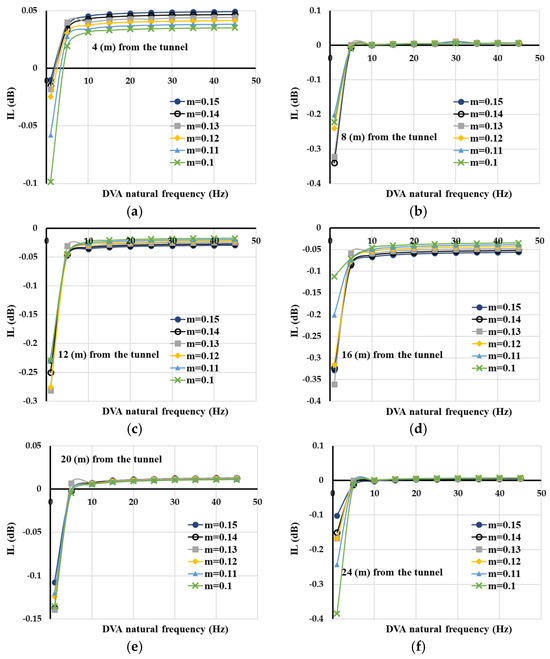

Figure 9.

Insertion loss against natural frequency of DVA when the tunnel surrounded with soft soil: (a) Receiver point at 4 (m) from tunnel axis; (b) receiver point at 8 (m) from tunnel axis; (c) receiver point at 12 (m) from tunnel axis; (d) receiver point at 16 (m) from tunnel axis; (e) receiver point at 20 (m) from tunnel axis; (f) receiver point at 24 (m) from tunnel axis.

As per the results elaborated in Figure 9, the most influential DVA was derived when the natural frequency was tuned to 1 (Hz) for all distances from the tunnel and for all DVA mass ratios. As the natural frequency is increased, DVA efficacy importantly falls. Results shown in Figure 9a reveal that when the receiver point was close to the tunnel, DVA that has a lower mass ratio has slightly better vibration dissipation for all natural frequencies. However, with an increase in the distance of the receiver point from the tunnel, similar to the results shown in Figure 8, DVA effectiveness is nearly constant. That is, as natural frequency increases more than 5 (Hz) while mass ratio increases, the insertion loss does not change. In fact, with an increase in DVA natural frequency, insertion loss becomes insensitive to DVA mass. Because the best result for insertion loss was obtained about −0.38 (dB) (which is lower than expected), the next round of parametric investigations was conducted to reach superior vibration reduction. In this round, the DVA mass ratio was gradually increased from 0.1 to 0.35, and the results derived are illustrated in Figure 10a–f.

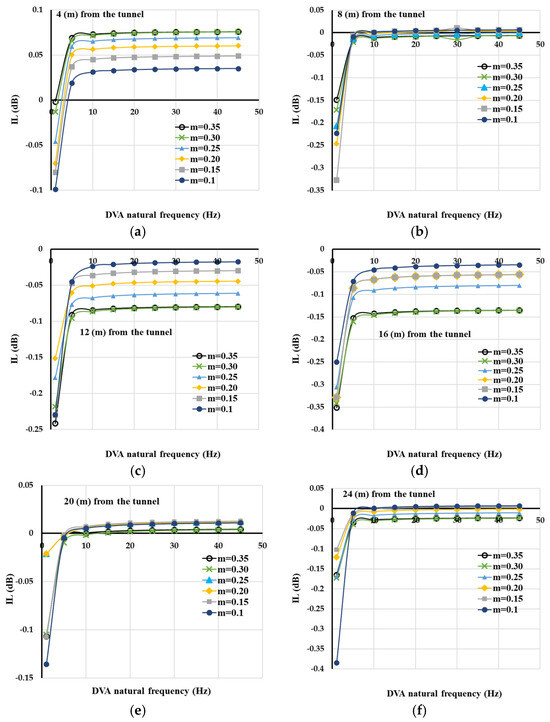

Figure 10.

Insertion loss against natural frequency of DVA when the tunnel is surrounded with soft soil: (a) Receiver point at 4 (m) from tunnel axis; (b) receiver point at 8 (m) from tunnel axis; (c) receiver point at 12 (m) from tunnel axis; (d) receiver point at 16 (m) from tunnel axis; (e) receiver point at 20 (m) from tunnel axis; (f) receiver point at 24 (m) from tunnel axis.

The trend of results illustrated in Figure 10a–f is similar to that depicted in Figure 8 and Figure 9. That is, the most effective DVA was achieved for DVA with the natural frequency of 1 (Hz). Also, when the natural frequency exceeds 5 (Hz), DVA effectiveness importantly drops and remains unchanged. For points at 12 (m) and 16 (m) from the tunnel, it was obtained that the most efficient DVA is the one that has the greatest mass ratio. Nevertheless, for the point at 4 (m) from the tunnel, the best performance of DVA was obtained when the mass ratio was reduced. This issue implies that DVA effectiveness is an important function of distance from the vibration source and mass ratio.

A survey of the obtained results unveils that the oscillation of DVA with high natural frequency cannot effectively dissipate vibration energy radiated on the ground surface. Also, the results disclose that the most effective DVA does not have a natural frequency close to the natural frequencies of the slab-tunnel system. This implies that assuming a complicated system such as a slab tunnel equipped with DVA is a two-degrees-of-freedom system is somewhat misleading. In fact, ground-borne vibration is highly dependent on soil characteristics and Rayleigh wave radiation. As a result, tuning DVA natural frequency to the natural frequencies of the slab-tunnel system cannot lead to the most vibration mitigation.

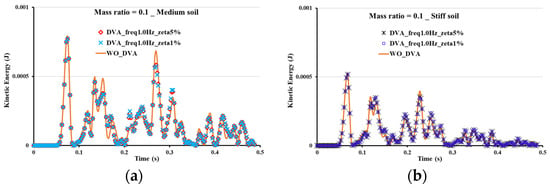

Hereafter, vibration propagated from metro tunnels surrounded with medium and stiff soil influenced by DVA was investigated. As depicted in Figure 11a,b, vibration amplitude was approximately constant and was not nearly varied when the track was equipped with DVA. Results of extensive parametric studies conducted on DVA natural frequency indicate that DVA effectiveness is insignificant as the tunnel is enclosed with medium and stiff soil. For instance, the vibration of a point on the ground surface at 4 (m) from the tunnel was not significantly changed by a DVA with a mass ratio of 0.1 and a natural frequency of 1 (Hz), as shown in Figure 11a,b. This discloses that the application of DVA in a tunnel surrounded with medium and stiff soil cannot efficiently lead to vibration dissipation. However, when the wave propagation medium is soft soil (i.e., the soil’s shear wave speed is less than 170 (m/s)), it can benefit from DVA to limited vibration.

Figure 11.

Time history of kinetic energy for the point located at 4 (m) from the tunnel surrounded with: (a) Medium soil and (b) stiff soil.

4. Discussion

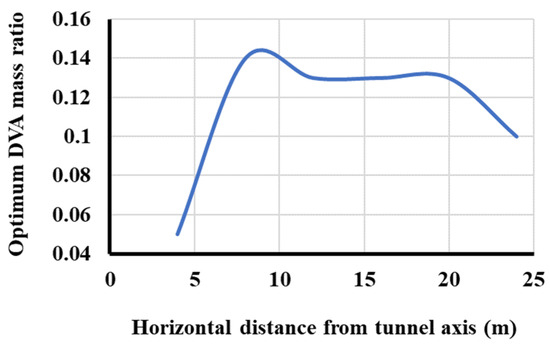

Outlining the results obtained from parametric studies indicates that the most vibration attenuation was gained when the DVA natural frequency is 1 (Hz) while the tunnel is enclosed with soft soil. In Figure 12, the optimum mass ratios of DVA for points at different distances from the tunnel are illustrated. As presented in Figure 12, due to the complex nature of wave propagation within the soil, the optimum mass ratio varied significantly with the horizontal distance of the receiver point from the source of vibration. Although Rayleigh wavelength was constant throughout the soil, the variation in insertion loss for different receiver points is not derived as a function of Rayleigh wavelength.

Figure 12.

Optimum values for DVA mass ratio.

In the present study, the highest level of vibration dissipation was achieved with a DVA that has a mass ratio of 0.1 and a natural frequency of 1 (Hz) for a point at 24 (m) from the tunnel (as presented in Figure 10f). In this condition, vibration decreased by 0.38 (dB). To evaluate the efficacy of DVA suggested in this study, the results derived here were compared with those available in the literature. Zhou et al. [24] implemented DVA under a slab track; their numerical studies indicate that DVA reduced slab acceleration by 40% in a narrow frequency range of 55 to 65 (Hz). However, the efficiency of the DVA suggested in [24] became negligible outside of this narrow frequency band. Zhu et al. [3] attached DVAs to a floating slab track. Their numerical analyses elucidate that slab accelerations were decreased by up to 20% in the frequency band of 10 to 20 (Hz); the slab acceleration was not influenced by DVA out of the frequency band [3]. Noori et al. [26] modeled a series of DVAs in a double-deck tunnel and derived that DVAs reduced vibration energy by 6.6 (dB) in a narrow frequency band in the vicinity of 31.5 (Hz). Kouroussis et al. [19] numerically assessed whether DVAs are more effective in the vehicle or on the track to mitigate vibration. Kouroussis et al. [19] obtained a reduction of 2 (dB) for the motorized wheel at the frequency of 20 (Hz) [19]; they derived that the response of the vehicle was negligibly reduced due to DVA being installed on the rail or sleeper [19]. A scrutiny of studies on the application of DVA in suppressing railway vibration reveals that DVA efficiency is limited to a narrow frequency band.

5. Conclusions

The main goal of this research is to evaluate the efficiency of using DVAs in underground railway tunnels to suppress vibrations induced by train passage. To this end, numerical modeling was performed in Abaqus FE software. The model includes a slab track, tunnel, and soil. The model was 2D and consisted of four-node plane strain elements. Artificial boundary conditions of damper-spring were used for model boundaries. The model results were validated by the use of the results derived from field measurements conducted in the Isfahan metro network. To investigate DVA performance, an impact load, same as the loading condition in the field test, was simulated as an excitation. Also, DVA was simulated near the slab track. Parametric studies were conducted on the natural frequency, mass ratio, and damping ratio of DVA in order to derive optimum properties of DVA that effectively mitigate ground-borne vibrations. In addition, three different soil properties (i.e., soft, medium, and stiff soils) were considered in parametric investigations. The natural frequency of DVA was tuned in harmony with the natural frequencies of the tunnel-track system that were derived from eigenvalue analysis. Also, natural frequencies of DVA were selected to be in a wide frequency band (i.e., from 1 (Hz) to 50 (Hz)). Results indicate that when a tunnel is surrounded with soft soil, DVAs with a mass ratio of 0.01 have negligible effects on vibration reduction. However, as the mass ratio of DVA is increased to 0.1, the vibration is decreased by 0.38 (dB). The results obtained reveal that augmentation of the damping ratio of DVA from 0.01 to 0.05 has no important effect on DVA efficiency. For medium and stiff soils, ground-borne vibration was not influenced by DVA. For further analysis of the DVA effect on vibration reduction, the DVA mass ratio was increased gradually to 0.35. The derived results disclose that the most effective DVA has a natural frequency of 1 (Hz). Also, the optimum DVA mass ratio ranges from 0.05 to 0.14 and depends on the receiver point’s distance from the tunnel. Results indicate that increasing the DVA mass ratio beyond 0.14 does not result in significant vibration suppression. Due to the practical limitations in underground tunnels, especially regarding tunnel clearance, DVAs with moderate mass ratios are recommended for metro tunnels. According to the results obtained, DVA with a natural frequency of 1 (Hz) and a damping ratio of 0.01 can moderately limit ground-borne vibration induced by metro tunnels built in soft soils. The results reveal that installing DVA adjacent to the slab track in the railway tunnel does not result in a significant reduction in vibration on the ground surface. Finally, it can be concluded that although DVA can control ground-borne vibration, the level of vibration suppression by DVA is limited in practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, A.T.; software, A.T. and S.M.; review and editing, A.T. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DVA | Dynamic vibration absorber |

| TMD | Tuned mass damper |

| FE | Finite element |

| RMS | Root mean square |

| SDOF | Single degree of freedom |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| PiP | Pipe-in-Pipe |

References

- Sadeghi, J.; Toloukian, A.; Shafieyoon, Y. Metro-induced vibration attenuation using rubberized concrete slab track. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 435, 136754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasheghani, M.; Sadeghi, J.; Khajehdezfuly, A. Legal consequences of train-induced structure borne noise and vibration in residential buildings. Noise Mapp. 2022, 9, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yang, J.; Yan, H.; Zhang, L.; Cai, C. Low-frequency vibration control of floating slab tracks using dynamic vibration absorbers. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2015, 53, 1296–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, J.; Esmaeili, M.H. Safe distance of cultural and historical buildings from subway lines. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 96, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.J.; Jiang, J.; Toward, M.G.R.; Hussein, M.F.M.; Dijckmans, A.; Coulier, P.; Degrande, G.; Lombaert, G. Mitigation of railway-induced vibration by using subgrade stiffening. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 79, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toward, M.G.; Jiang, J.; Dijckmans, A.; Coulier, P.; Thompson, D.J.; Degrande, G.; Lombaert, G.; Hussein, M.F. Mitigation of railway induced vibrations by using subgrade stiffening and wave impeding blocks. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Structural Dynamics (EURODYN 2014), Porto, Portugal, 30 June–2 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ardian, A.R.R.; Handayani, D.; Marzuki, A. A Review: Vibration Caused by Transportation. Eng. Proc. 2025, 84, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mendoza, D.; Romero, A.; Connolly, D.P.; Galvín, P. Scoping methodology to assess induced vibration by railway traffic in buildings. Procedia Eng. 2017, 199, 2717–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, W.; Shang, Y.; Su, N.; Feng, D. Field Test Study on the dynamic response of the cement-improved expansive soil subgrade of a heavy-haul railway. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 128, 105878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Kordestani, H.; Shadabfar, M. A combined review of vibration control strategies for high-speed trains and railway infrastructures: Challenges and solutions. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 2023, 42, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouroussis, G.; Connolly, D.P.; Verlinden, O. Railway-induced ground vibrations—A review of vehicle effects. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2014, 2, 69–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouroussis, G.; Mouzakis, H.P.; Vogiatzis, K.E. Structural impact response for assessing railway vibration induced on buildings. Mech. Ind. 2017, 18, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazi, M.K.A.M.; Adnan, M.A.; Sulaiman, N. The Impact of Train Operation Time with Ground Borne Vibration Induced by Railway Traffic. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 971, p. 012004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zheng, H.; Tang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhao, R.; Lu, Y.; Aw, K.C. Vibration-based and computer vision-aided nondestructive health condition evaluation of rail track structures. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, B.; Cubría, V.; Arcos, R.; Clot, A.; Romeu, J. Optimization of Dynamic Vibration ABSORBERS placed on the Tunnel Interior Surface to Mitigate Underground Railway-Induced Vibration. In Proceedings of the 9th Iberian Acoustics Congress, 47th Spanish Congress on Acoustics, Porto, Portugal, 13–15 June 2016; Tecniacústica 2016; Sociedade Portuguesa de Acústica. EuroRegio: Gronau, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Noori, B.; Arcos, R.; Clot, A.; Romeu, J. Control of ground-borne underground railway-induced vibration from double-deck tunnel infrastructures by means of dynamic vibration absorbers. J. Sound Vib. 2019, 461, 114914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, D. Controlling the vibration and noise of a ballasted track using a dynamic vibration absorber with negative stiffness. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2020, 234, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yang, J.; Cai, C.; Pan, Z.; Zhai, W. Application of dynamic vibration absorbers in designing a vibration isolation track at low-frequency domain. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2017, 231, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouroussis, G.; Ainalis, D.; Zhu, S.; Zhai, W. Mitigation measures for urban railway induced ground vibrations using dynamic vibration absorbers. In Proceedings of the 25th International Congress on Sound and Vibration (ICSV25), Hiroshima, Japan, 8–12 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, N.; Fujino, Y.; Warnitchai, P. Optimal tuned mass damper for seismic applications and practical design formulas. Eng. Struct. 2008, 30, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S. Mechanical Vibrations, 5th ed.; Chapter 9 Vibration Control; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fujino, Y.; Abé, M. Design formulas for tuned mass dampers based on a perturbation technique. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1993, 22, 833–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, J.J. Introduction to Structural Motion Control; Chapter 4 Tuned Mass Damper Systems; Prentice Hall Pearson Education, Incorporated: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, T.; Luo, Y. Parametric study of dynamic vibration absorber with negative stiffness applied to floating slab track. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25, 3369–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, J.; Cai, C.; Wang, K.; Zhai, W.; Yang, J.; Yan, H. Development of a vibration attenuation track at low frequencies for urban rail transit. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2017, 32, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, B.; Arcos, R.; Clot, A.; Romeu, J. Assessment of Dynamic Vibration Absorbers Efficiency as a Counter-Measure for Ground-Borne Vibrations Induced by Train Traffic in Double-Deck Tunnels Using an Energy Flow Criterion. In Noise and Vibration Mitigation for Rail Transportation Systems, Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Railway Noise, Ghent, Belgium, 16–20 September 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 454–461. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, L. Simulations and analyses of train-induced ground vibrations in finite element models. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2003, 23, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, H.R.; Degrande, G. Numerical modeling of free field vibrations due to pile driving using a dynamic soil-structure interaction formulation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2008, 215, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysmer, J.; Kuhlemeyer, R.L. Finite dynamic model for infinite media. J. Eng. Mech. Div. 1969, 95, 859–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Du, Y.; Du, X.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J. 3D viscous-spring artificial boundary in time domain. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2006, 5, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudreau, G.L.; Taylor, R.L. Evaluation of numerical integration methods in elastodynamics. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1973, 2, 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.J.; Jiang, J.; Toward, M.G.R.; Hussein, M.F.M.; Ntotsios, E.; Dijckmans, A.; Coulier, P.; Lombaert, G.; Degrande, G. Reducing railway-induced ground-borne vibration by using open trenches and soft-filled barriers. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2016, 88, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehdezfuly, A.; Shiraz, A.A.; Sadeghi, J. Assessment of vibrations caused by simultaneous passage of road and railway vehicles. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 211, 109510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.J.; Kouroussis, G.; Ntotsios, E. Modelling, simulation and evaluation of ground vibration caused by rail vehicles. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2019, 57, 936–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, S.P. Railway Induced Vibration-State of the Art Report; UIC-ETC (Railway Technical Publications): Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, J. Study, Experimental Analysis and Field Test on Isfahan Metro: Exploring Influence of Ground-Borne Vibration on Historical Buildings and Cultural Heritage; Technical Report conducted at IUST Led by J. Sadeghi, Research Report-2015-SRE; School of Railway Engineering, Iran University of Science and Technology: Tehran, Iran, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbitt, Karlsson and Sorensen, Inc. ABAQUS User’s Manual, version 6.8-1; Hibbitt, Karlsson and Sorensen: Providence, RI, USA, 2008.

- Wair, B.R.; DeJong, J.T.; Shantz, T. Guidelines for Estimation of Shear Wave Velocity Profiles; PEER Report 2012-08; Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, J.P.; Hunt, H.E.M. Isolation of buildings from rail-tunnel vibration: A review. Build. Acoust. 2003, 10, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).