Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of High-Entropy Composite in a Ti–Cr–Mn–Co–Ni–Al–C System

Abstract

1. Introduction

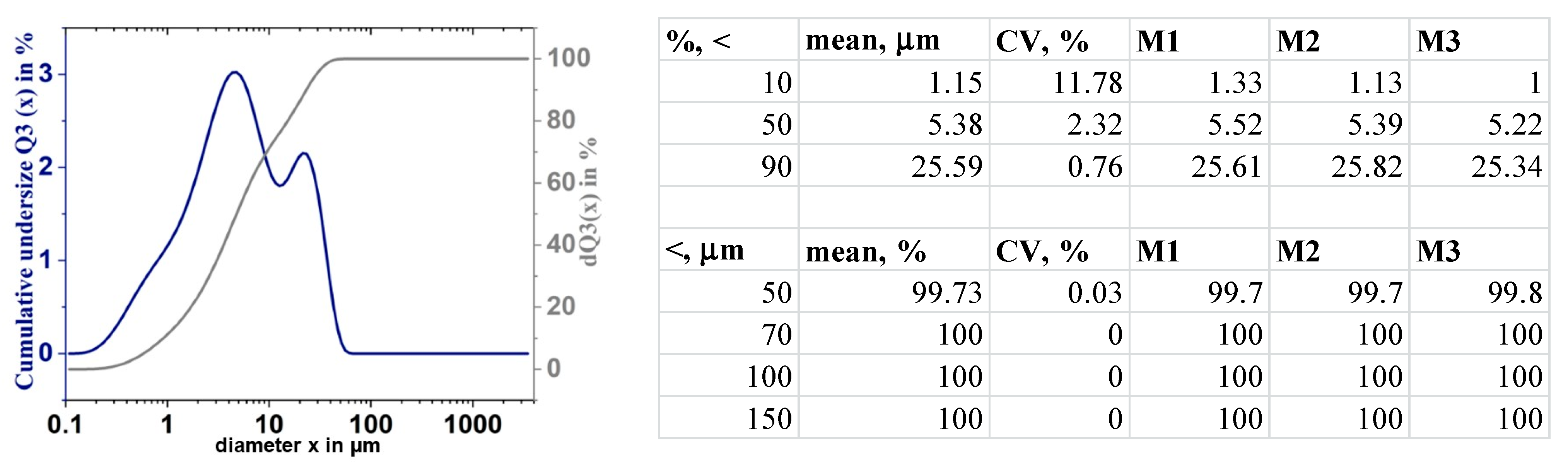

2. Materials and Methods

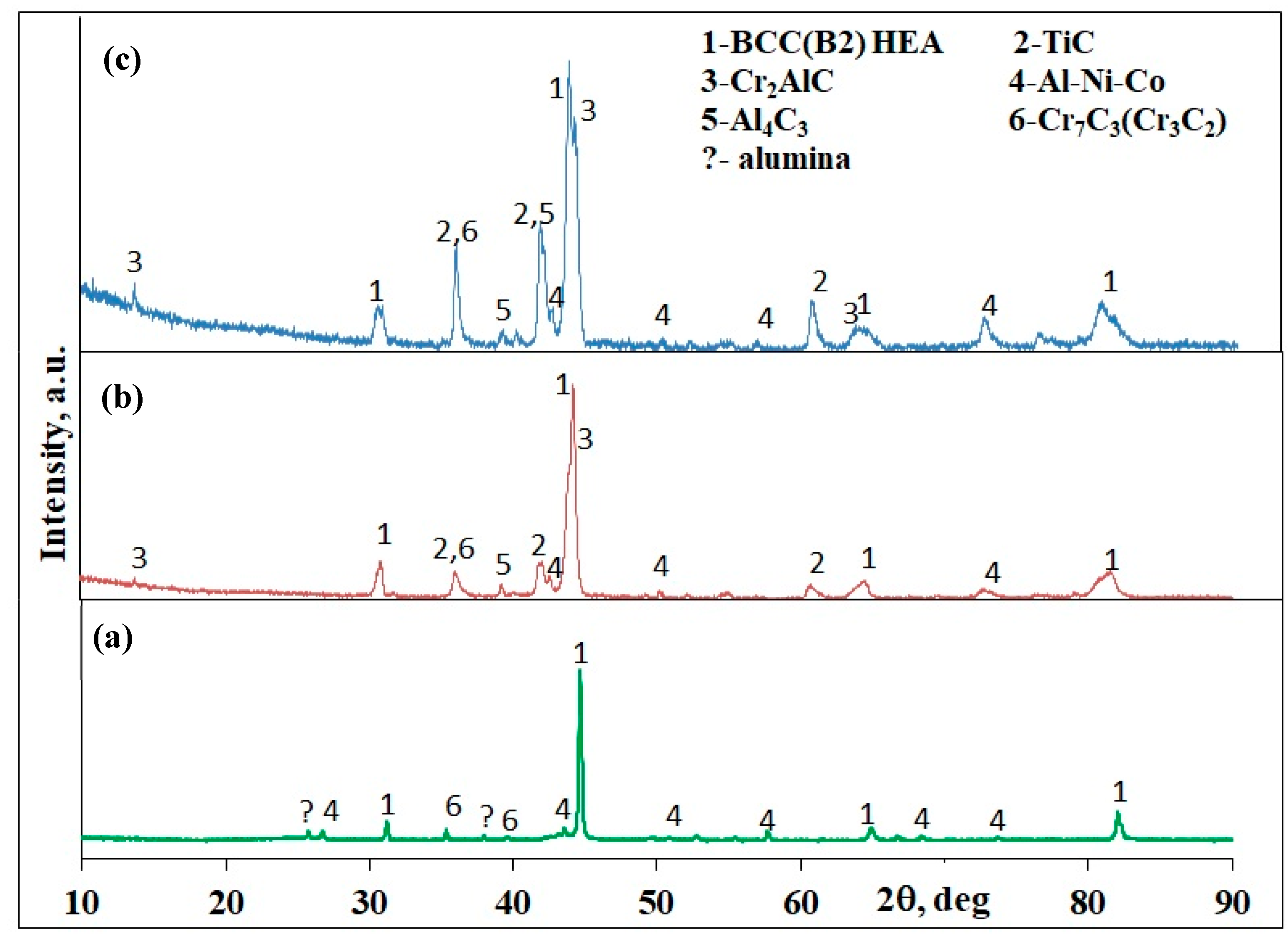

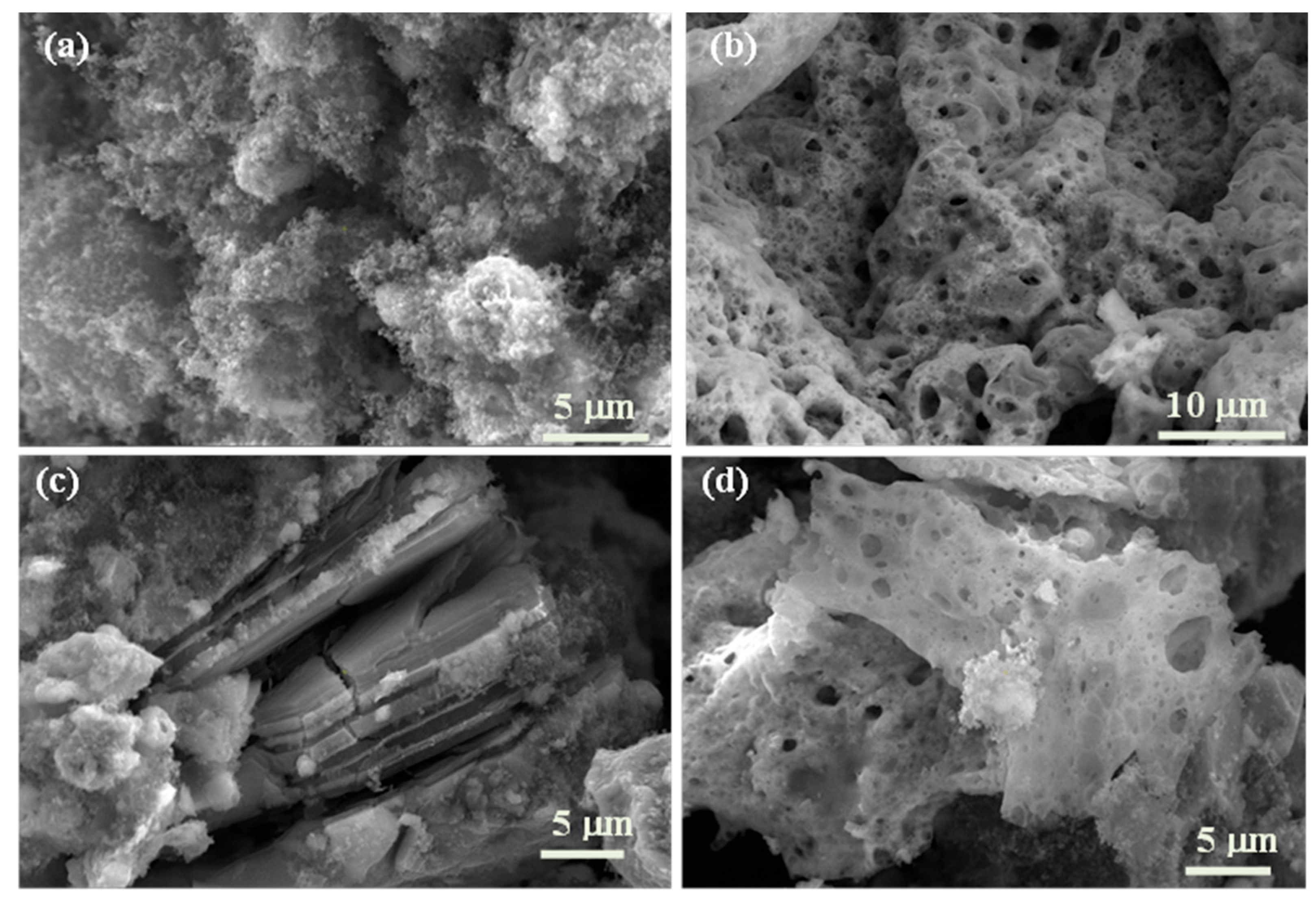

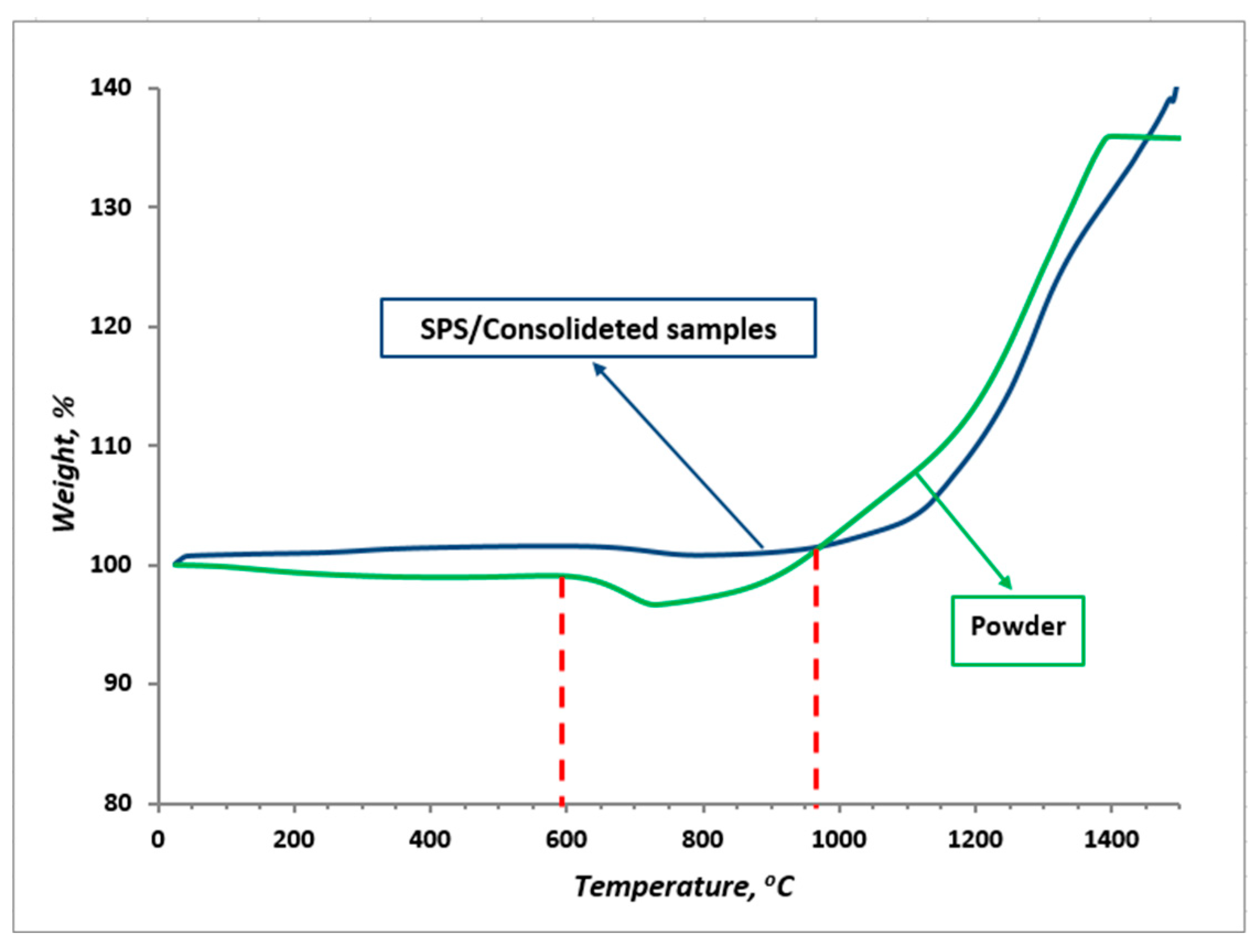

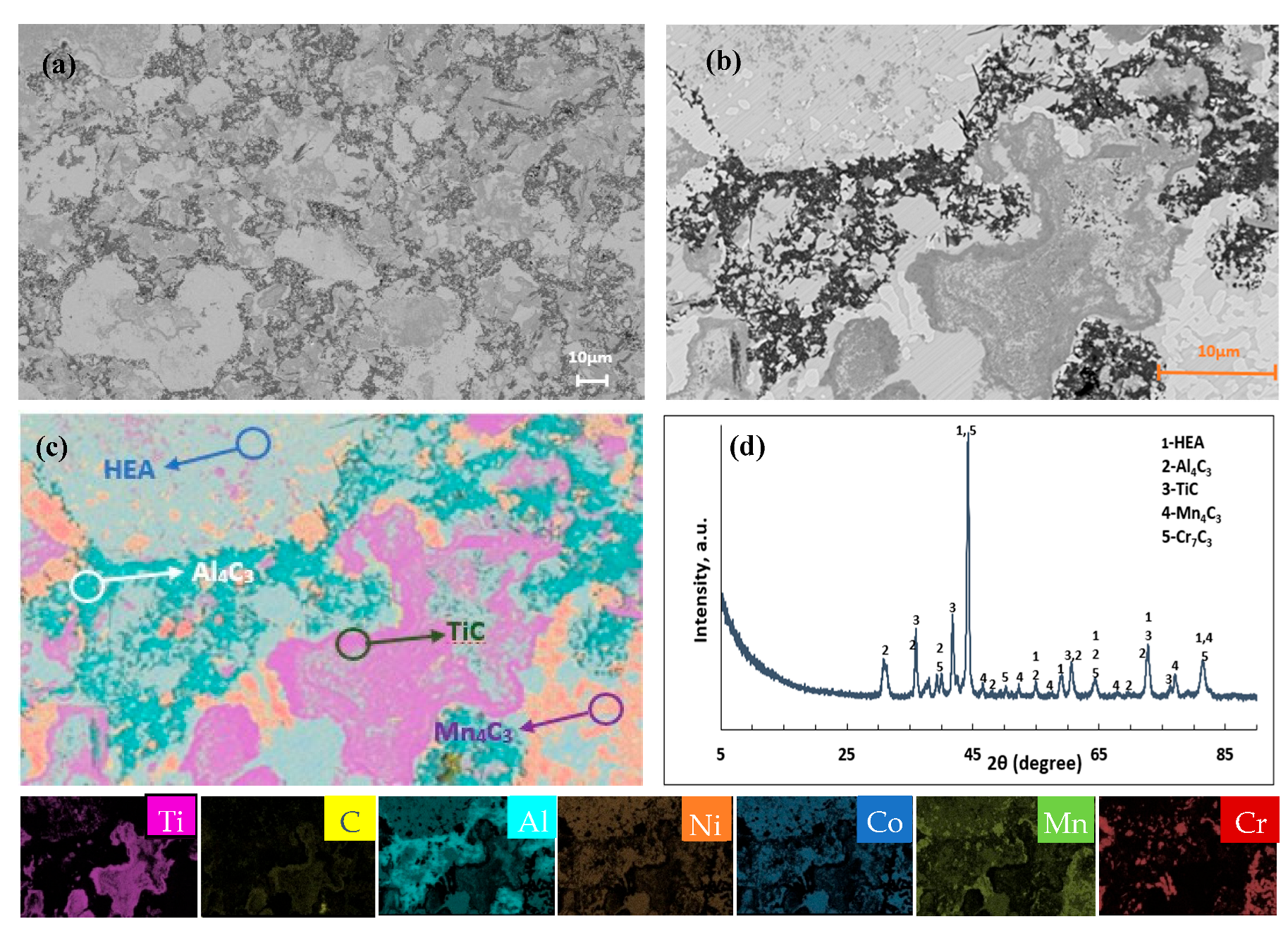

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H. Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys with Multiple Principal Elements: Novel Alloy Design Concepts and Outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and Properties of High-Entropy Alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 61, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.K.; Yeh, J.W.; Shun, T.T.; Chen, S.K. Multi-Principal-Element Alloys with Improved Oxidation and Wear Resistance for Thermal Spray Coating. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, S.; Liu, C.T. Phase Selection in High-Entropy Alloys: From Nonequilibrium to Equilibrium. JOM 2014, 35, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, K.M.; Zaddach, A.J.; Niu, C.; Irving, D.L.; Koch, C.C. A Novel Low-Density, High-Hardness, High-Entropy Alloy with Close-Packed Single-Phase Nanocrystalline Structures. Mater. Res. Lett. 2015, 3, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A Critical Review of High-Entropy Alloys and Related Concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.P.; Raabe, D.; Ritchie, R.O. High-Entropy Alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pradeep, K.G.; Deng, Y.; Raabe, D.; Tasan, C.C. Metastable High-Entropy Dual-Phase Alloys Overcome the Strength–Ductility Trade-Off. Nature 2016, 534, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonar, T.; Koli, D.K.; Agrawal, A.; Vashishtha, N.; Sonar, S. An Overview of Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Advanced Applications of High-Entropy Alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 4822–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y. Recent Progress in High-Entropy Alloys: A Focused Review. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2024, 34, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Kumkale, V.Y.; Hou, H.; Kadam, V.S.; Jagtap, C.V.; Lokhande, P.E.; Pathan, H.M.; Pereira, A.; Lei, H.; Liu, T.X. A Review of High-Entropy Materials with Their Unique Applications. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caramarin, S.; Badea, I.C.; Mosinoiu, L.F.; Mitrica, D.; Serban, B.A.; Vitan, N.; Cursaru, L.M.; Pogrebnjak, A. Structural Particularities, Prediction, and Synthesis in High-Entropy Alloys. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutor, R.K.; Cao, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.-Z. Phase selection, lattice distortions, and mechanical properties in high-entropy alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 2000466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Eivani, A.R.; Abbasi, S.M.; Jafarian, H.R.; Ghosh, M.; Anijdan, S.H.M. Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Ni-Ti high entropy alloys: A review of microstructural and mechanical properties at elevated temperatures. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huang, H.; Su, Y.; Qiao, L.; Yan, Y. Exploring high corrosion-resistant refractory high-entropy alloy via a combined experimental and simulation study. npj Mater. Degrad. 2024, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, X. Microstructure, wear and corrosion resistance mechanism of as-cast lightweight refractory NbMoZrTiX (X = al, V) high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Hao, Z.; Hao, W.; Mo, Z.; Li, L. Tunable magnetic phase transition and magnetocaloric effect in the rare-earth-free Al-Mn-Fe-Co-Cr high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Des. 2023, 229, 111894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, R.; Zalesak, J.; Matko, I.; Baumegger, W.; Hohenwarter, A.; George, E.P.; Keckes, J. Microstructure-dependent phase stability and precipitation kinetics in equiatomic CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy: Role of grain boundaries. Acta Mater. 2022, 223, 117470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, M.; Wróbel, J.S.; Fernández-Caballero, A.; Kurzydłowski, K.J.; Nguyen-Manh, D. Phase stability and magnetic properties in fcc Fe-Cr-Mn-Ni alloys from first-principles modeling. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 174416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzhanov, A.G. History and recent developments in SHS. Ceram. Int. 1995, 21, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzhanov, A.G.; Borovinskaya, I.P. Historical retrospective of SHS: An autoreview. J. Self-Propagating High-Temp. Synth. 2008, 17, 242–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuskov, K.V.; Nepapushev, A.A.; Aydinyan, S.; Shaysultanov, D.G.; Stepanov, N.D.; Nazaretyan, K.; Moskovskikh, D.O. Combustion Synthesis and Reactive Spark Plasma Sintering of Non-Equiatomic CoAl-Based High-Entropy Intermetallics. Materials 2023, 16, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolay, E.; Filippov, V.; Linnik, A.; Mironov, A. Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of Hf–Ti–Fe–V–Cr–N High-Entropy Ceramic Material. Mater. Lett. 2023, 344, 134434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, D.; Wang, Q.; Deng, B.; Li, Y.; Huang, A.; Cheng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li., J.; Li., Y.; Yao., W.; et al. Liquid metal assistant self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of S-containing high-entropy MAX-phase materials. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 209, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinyan, S. Combustion synthesis of MAX phases: Microstructure and properties inherited from the processing pathway. Crystals 2023, 13, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seplyarskii, B.S.; Abzalov, N.I.; Kochetkov, R.A.; Lisina, T.G.; Kovalev, D.Y. Combustion synthesis of TiC-high entropy alloy CoCrFeNiMn composites from granular mixtures. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 39159–39166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogachev, A.S.; Vadchenko, S.G.; Kochetov, N.A.; Kovalev, D.Y.; Kovalev, I.D.; Shchukin, A.S.; Gryadunov, A.N.; Baras, F.; Politano, O. Combustion synthesis of TiC-based ceramic-metal composites with high entropy alloy binder. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 2527–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, J. Microstructure and mechanical properties regulation and control of in-situ TiC reinforced CoCrFeNiAl0.2 high-entropy alloy matrix composites via high-gravity combustion route. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 899, 163221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamyan, S.S. Thermodynamic analysis of SHS processes. Key Eng. Mater. 2001, 217, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.O.; Li, S.B.; Song, G.; Sloof, W.G. Synthesis and thermal stability of Cr2AlC. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 31, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, G.; Wan, H.; Deng, C.; Di, J.; Ding, J.; Ma, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Yu, C. Thermal stability and selective nitridation of Cr2AlC in nitrogen at elevated temperatures. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 33151–33159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Wang, X.; Li, G.; Lu, C.; Zhang, J.; Tu, R. Synthesis of Cr2AlC from elemental powders with modified pressureless spark plasma sintering. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2019, 34, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Niu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Li, J.; Bai, G.; Ke, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, C. Microstructure and wear behavior of in-situ synthesized TiC-reinfirced CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy prepared by laser cladding. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 670, 160720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Huang, S.R.; Zhu, C.Y.; Zhang, J.F.; Zhu, H.G.; Xie, Z.H. In Situ TiC/FeCrNiCu High-Entropy Alloy Matrix Composites: Reaction Mechanism, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Acta Metall. Sin. 2020, 33, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Wu, H.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, N.; Yin, Y.; Liang, L.; Huang, W. Microstructures and Tribological Properties of TiC Reinforced FeCoNiCuAl High-Entropy Alloy at Normal and Elevated Temperature. Metals 2020, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Fang, Q.; Liu, Y. Ultra-High Strength TiC/Refractory High-Entropy-Alloy Composite Prepared by Powder Metallurgy. JOM 2017, 69, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Tong, Y.; Hu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, X.; Hua, M.; Xu, S.; Mei, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, Z. Wear-Resistant TiC Strengthening CoCrNi-Based High-Entropy Alloy Composite. Materials 2021, 14, 4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, M.; Zhu, M.; Yao, L.; Jian, Z. Oxidation Behavior of (AlCoCrFeNi)92(TiC)8 High-Entropy Alloy at Elevated Temperatures. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 8100–8110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarjuna, C.; Dewangana, S.K.; Lee, K.; Ahn, B. Mechanical and thermal expansion behaviour of TiC-reinforced CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy prepared by mechanical alloying and spark plasma sintering. Powder Metall. 2023, 66, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

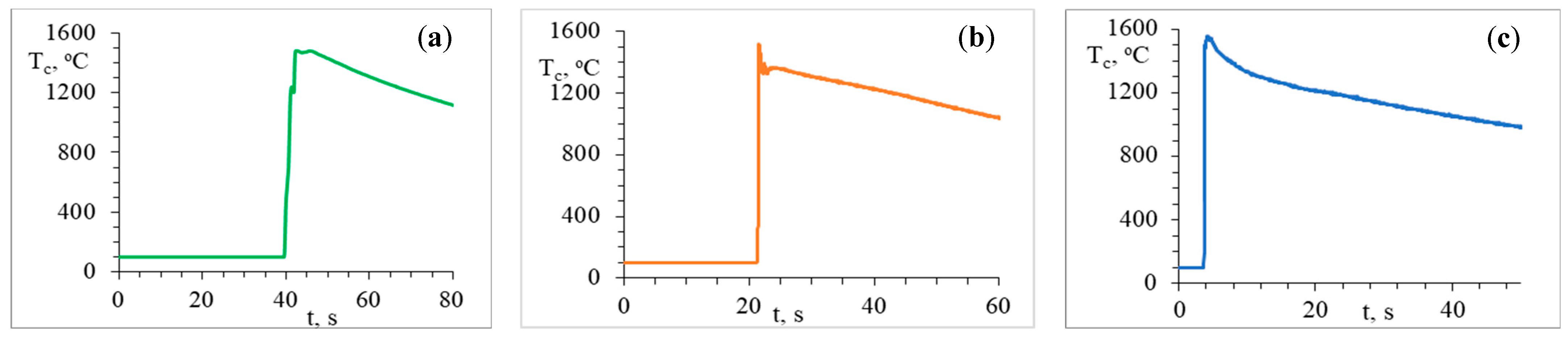

| System | Tc, °C | Uc, mm/s | Vh, °C/s | Vc, °C/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3Cr-0.3Mn-1.2Co-1.2Ni-2Al-2C | 1480 ± 10 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 292 ± 15 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

| 0.4Ti-0.4Cr-0.4Mn-0.4Co-0.4Ni-1.5Al-1C | 1520 ± 10 | 0.70 ± 0.01 | 882 ± 44 | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

| 0.9Ti-0.6Cr-0.6Mn-0.6Co-0.3Ni-2Al-2C | 1560 ± 10 | 4.30 ± 0.02 | 1726 ± 86 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zurnachyan, A.; Ginosyan, A.; Ivanov, R.; Hussainova, I.; Aydinyan, S. Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of High-Entropy Composite in a Ti–Cr–Mn–Co–Ni–Al–C System. Ceramics 2025, 8, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040137

Zurnachyan A, Ginosyan A, Ivanov R, Hussainova I, Aydinyan S. Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of High-Entropy Composite in a Ti–Cr–Mn–Co–Ni–Al–C System. Ceramics. 2025; 8(4):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040137

Chicago/Turabian StyleZurnachyan, Alina, Abraam Ginosyan, Roman Ivanov, Irina Hussainova, and Sofiya Aydinyan. 2025. "Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of High-Entropy Composite in a Ti–Cr–Mn–Co–Ni–Al–C System" Ceramics 8, no. 4: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040137

APA StyleZurnachyan, A., Ginosyan, A., Ivanov, R., Hussainova, I., & Aydinyan, S. (2025). Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of High-Entropy Composite in a Ti–Cr–Mn–Co–Ni–Al–C System. Ceramics, 8(4), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040137