Phase Formation Study of Solid-State LLZNO and LLZTO via Structural, Thermal, and Morphological Analyses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.1.1. Raw Materials

2.1.2. Preparation of Precursor Powders

2.1.3. Preparation of Calcined-Doped LLZO Powders

2.2. Characterization

2.2.1. In Situ High-Temperature XRD of Precursor Powders

2.2.2. TGA/DSC Analysis of Precursor Powders

2.2.3. Structural and Microstructural Analyses of Calcined Powders at Various Temperatures

3. Results

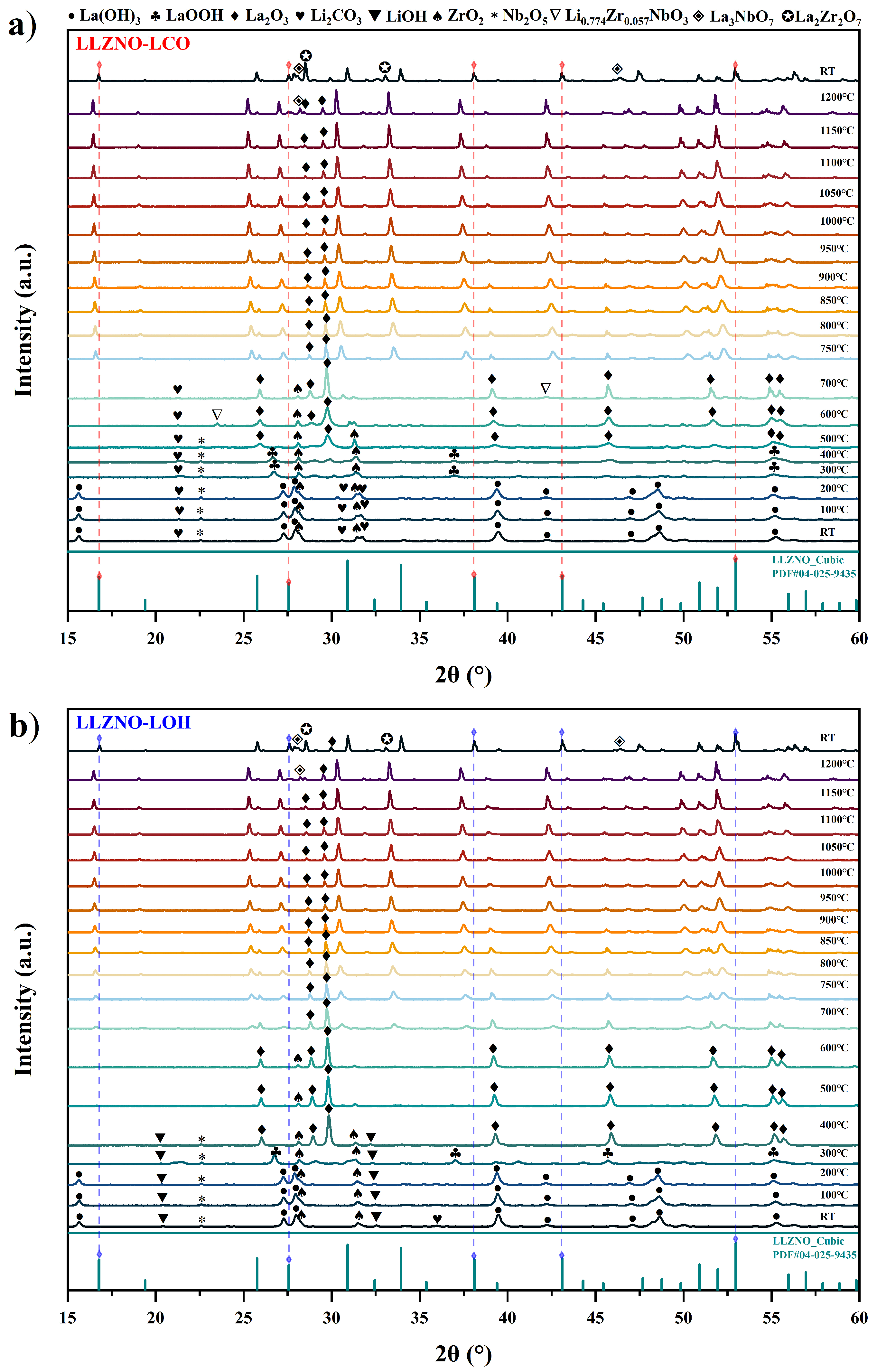

3.1. Phase Formation of Doped LLZO During HT-XRD Analysis

3.2. Thermal Stability Analysis of Doped LLZO

3.3. Structural and Morphology Analyses of Calcined-Doped LLZO Powders

3.3.1. Phase Chemistry of Calcined Doped LLZO Powders

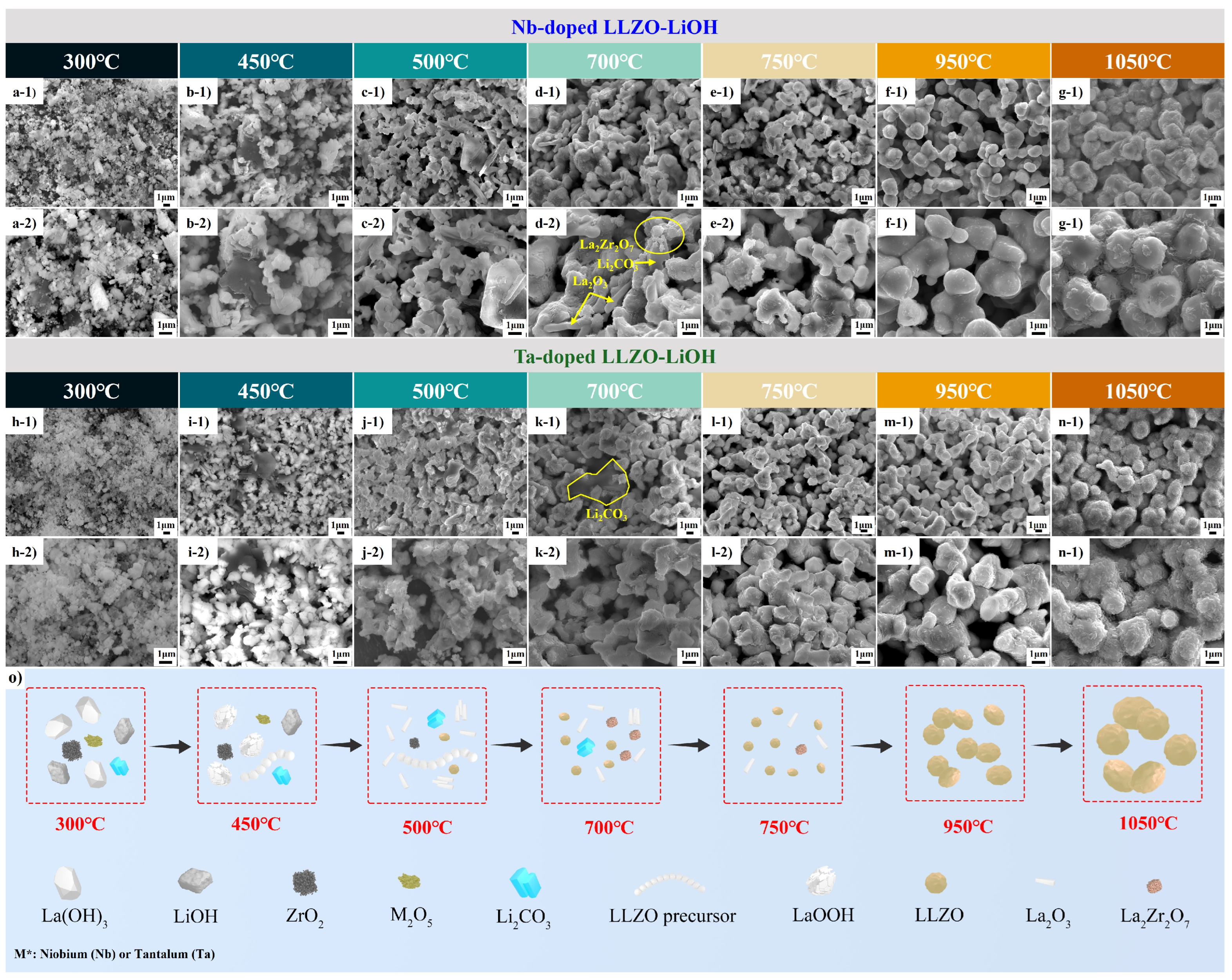

3.3.2. Morphology Evolution of Calcined-Doped LLZO Powders

4. Discussion

4.1. Emergence of Secondary Phases

4.2. Comparison of Li2CO3 and LiOH as Lithium Precursor

4.3. Comparison of Nb2O5 and Ta2O5 as Dopant

4.4. Implications of Gas Atmosphere and Sample Volume

4.5. Influence Factors for the Calcination Processing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheng, O.; Jin, C.; Ding, X.; Liu, T.; Wan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Nai, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Tao, X. A decade of progress on solid-state electrolytes for secondary batteries: Advances and Contributions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wen, K.; Fan, J.; Bando, Y.; Golberg, D. Progress and future prospects of high-voltage and high-safety electrolytes in advanced lithium batteries: From liquid to solid electrolytes. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 11631–11663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiram, A.; Yu, X.; Wang, S. Lithium battery chemistries enabled by solid-state electrolytes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 16103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmaltz, T.; Hartmann, F.; Wicke, T.; Weymann, L.; Neef, C.; Janek, J. A Roadmap for Solid-State Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2301886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Fu, K.; Kammampata, S.P.; McOwen, D.W.; Samson, A.J.; Zhang, L.; Hitz, G.T.; Nolan, A.M.; Wachsman, E.D.; Mo, Y.; et al. Garnet-Type Solid-State Electrolytes: Materials, Interfaces, and Batteries. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 4257–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, T.; Yu, S.; Williams, L.; Schmidt, R.D.; Garcia-Mendez, R.; Wolfenstine, J.; Allen, J.L.; Kioupakis, E.; Siegel, D.J.; Sakamoto, J. Electrochemical window of the Li-Ion solid electrolyte Li7La3Zr2O12. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Rangasamy, E.; dela Cruz, C.R.; Liang, C.; An, K. A study of suppressed formation of low-conductivity phases in doped Li7La3Zr2O12 garnets by in situ neutron diffraction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 22868–22876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, C.A.; Alekseev, E.; Lazic, B.; Fisch, M.; Armbruster, T.; Langner, R.; Fechtelkord, M.; Kim, N.; Pettke, T.; Weppner, W. Crystal chemistry and stability of “Li7La3Zr2O12” garnet: A fast lithium-ion conductor. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaka, J.; Kijima, N.; Hayakawa, H.; Akimoto, J. Synthesis and structure analysis of tetragonal Li7La3Zr2O12 with the garnet-related type structure. J. Solid State Chem. 2009, 182, 2046–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, N.; Johannes, M.D.; Hoang, K. Origin of the Structural Phase Transition in Li7La3Zr2O12. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 205702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miara, L.J.; Richards, W.D.; Wang, Y.E.; Ceder, G. First-principles studies on cation dopants and electrolyte | cathode interphases for lithium garnets. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 4040–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Rangasamy, E.; Liang, C.; An, K. Origin of High Li+ Conduction in Doped Li7La3Zr2O12 Garnets. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košir, J.; Mousavihashemi, S.; Wilson, B.P.; Rautama, E.L.; Kallio, T. Comparative analysis on the thermal, structural, and electrochemical properties of Al-doped Li7La3Zr2O12 solid electrolytes through solid state and sol-gel routes. Solid State Ion. 2022, 380, 115943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Park, J.S.; Hou, H.; Zorba, V.; Chen, G.; Richardson, T.; Cabana, J.; Russo, R.; Doeff, M. Effect of microstructure and surface impurity segregation on the electrical and electrochemical properties of dense Al-substituted Li7La3Zr2O12. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, Y.; Sakamoto, K.; Matsui, M.; Yamamoto, O.; Takeda, Y.; Imanishi, N. Phase formation of a garnet-type lithium-ion conductor Li7−3xAlxLa3Zr2O12. Solid State Ion. 2015, 277, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheld, W.S.; Collette, Y.; Schwab, C.; Ihrig, M.; Uhlenbruck, S.; Finsterbusch, M.; Fattakhova-Rohlfing, D. Ga-ion migration during co-sintering of heterogeneous Ta- and Ga-substituted LLZO solid-state electrolytes. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 116936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miara, L.J.; Ong, S.P.; Mo, Y.; Richards, W.D.; Park, Y.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, H.S.; Ceder, G. Effect of Rb and Ta Doping on the Ionic Conductivity and Stability of the Garnet Li7+2x–y(La3–xRbx)(Zr2–yTay)O12 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.375, 0 ≤ y ≤ 1) Superionic Conductor: A First Principles Investigation. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 3048–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Xie, W.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Qiu, J.; Chen, J.; Zhao, P. Effect of Nb and Ta Simultaneous Substitution on Self-Consolidation Sintering of Li7La3Zr2O12. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 7559–7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhou, C.; Lin, F.; Li, B.; Yang, F.; Zhu, H.; Duan, J.; Chen, Z. Submicron-Sized Nb-Doped Lithium Garnet for High Ionic Conductivity Solid Electrolyte and Performance of Quasi-Solid-State Lithium Battery. Materials 2020, 13, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, X.; Nie, Z.; Wu, C.; Zheng, N.; Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Wei, R.; Yu, J.; Yang, N.; et al. High-performance Ta-doped Li7La3Zr2O12 garnet oxides with AlN additive. J. Adv. Ceram. 2022, 11, 1530–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parascos, K.; Watts, J.L.; Alarco, J.A.; Talbot, P.C. Tailoring calcination products for enhanced densification of Li7La3Zr2O12 Ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, J.; Chen, F.; Tu, R.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L. Preparation of cubic Li7La3Zr2O12 solid electrolyte using a nanosized core-shell structured precursor. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 644, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badami, P.; Smetaczek, S.; Limbeck, A.; Rettenwander, D.; Chan, C.K.; Kannan, A.N.M. Facile synthesis of Al-stabilized lithium garnets by a solution-combustion technique for all solid-state batteries. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullbrekken, Ø.; Eggestad, K.; Tsoutsouva, M.; Williamson, B.A.; Rettenwander, D.; Einarsrud, M.A.; Selbach, S.M. Phase Evolution and Thermodynamics of Cubic Li6.25Al0.25La3Zr2O12 Studied by High-Temperature X-ray Diffraction. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 5856–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deviannapoorani, C.; Ramakumar, S.; Janani, N.; Murugan, R. Synthesis of lithium garnets from La2Zr2O7 pyrochlore. Solid State Ion. 2015, 283, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.M.; Dopilka, A.; Chan, C.K. Observation of elemental inhomogeneity and its impact on ionic conductivity in Li-conducting garnets prepared with different synthesis methods. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2021, 2, 2000109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parascos, K.; Watts, J.L.; Alarco, J.A.; Chen, Y.; Talbot, P.C. Compositional and structural control in LLZO solid electrolytes. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 23466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, M.; Takahashi, K.; Sakamoto, K.; Hirano, A.; Takeda, Y.; Yamamoto, O.; Imanishi, N. Phase stability of a garnet-type lithium ion conductor Li7La3Zr2O12. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppiah, D.; Komissarenko, D.; Yüzbasi, N.S.; Liu, Y.; Warriam Sasikumar, P.V.; Hadian, A.; Graule, T.; Clemens, F.; Blugan, G. A Facile Two-Step Thermal Process for Producing a Dense, Phase-Pure, Cubic Ta-Doped Lithium Lanthanum Zirconium Oxide Electrolyte for Upscaling. Batteries 2023, 9, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Qin, S.; Wu, X. Thermal Behavior of Pyromorphite (Pb10(PO4)6Cl2): In Situ High Temperature Powder X-ray Diffraction Study. Crystals 2020, 10, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushotham, N.; Santhy, K.; Suresh Babu, P.; Sivakumar, G.; Rajasekaran, B. In Situ High-Temperature X-ray Diffraction Study on Atmospheric Plasma and Detonation Sprayed Ni-5 wt.%Al Coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2023, 32, 2091–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.G.; Kim, Y.I.; Cho, D.W.; Sohn, Y. Synthesis and physicochemical properties of La(OH)3 and La2O3 nanostructures. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2015, 40, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yow, Z.F.; Oh, Y.L.; Gu, W.; Rao, R.P.; Adams, S. Effect of Li+/H+ exchange in water treated Ta-doped Li7La3Zr2O12. Solid State Ion. 2016, 292, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Ge, J.; Wu, C.; Zhuo, L.; Niu, J.; Chen, Z.; Shi, Z.; Dong, Y. Sol-solvothermal synthesis and microwave evolution of La(OH)3 nanorods to La2O3 nanorods. Nanotechnology 2004, 15, 1273–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.A.; Lin, P.; Wang, S.F. Microstructures and microwave dielectric properties of Li2O–Nb2O5–ZrO2 ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2007, 33, 1389–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, H.; Meini, S.; Tsiouvaras, N.; Piana, M.; Gasteiger, H.A. Thermal and electrochemical decomposition of lithium peroxide in non-catalyzed carbon cathodes for Li-air batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 11025–11037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Lu, Y.; Guo, H.; Song, Z.; Xiu, T.; Badding, M.E.; Wen, Z. None-mother-powder method to prepare dense Li-garnet solid electrolytes with high critical current density. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 5355–5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lu, Y.; Song, Z.; Rui, K.; Wang, Q.; Xiu, T.; Badding, M.E.; Wen, Z. Manipulating Li2O atmosphere for sintering dense Li7La3Zr2O12 solid electrolyte. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 22, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiat, J.M.; Boemare, G.; Rieu, B.; Aymes, D. Structural evolution of LiOH: Evidence of a solid–solid transformation toward Li2O close to the melting temperature. Solid State Commun. 1998, 108, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zeng, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Xu, H.; Bai, Y.; Deng, L.; He, Z.; Huang, H. Lithium Hydroxide Reaction for Low Temperature Chemical Heat Storage: Hydration and Dehydration Reaction. Energies 2019, 12, 3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, E.; Wang, W.; Kieffer, J.; Laine, R.M. Flame made nanoparticles permit processing of dense, flexible, Li+ conducting ceramic electrolyte thin films of cubic-Li7La3Zr2O12 (c-LLZO). J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 12947–12954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Liu, C.; Kuang, X.; Mi, J.; Liang, H.; Su, Q. Synthesis and luminescence properties of the lithium-containing lanthanum-oxycarbonate-like borates. J. Solid State Chem. 2012, 194, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Ma, J.; Zhu, Q.; Li, J.G. Phase evolution, structure, and up-/down-conversion luminescence of Li6CaLa2Nb2O12: Yb3+/RE3+ phosphors (RE = Ho, Er, Tm). J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 103, 2674–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.; Rahman, A.A.; Mohamed, N.S. Sol-gel synthesis and characterization of Li2CO3-Al2O3 composite solid electrolytes. Ionics 2016, 22, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Connell, J.G.; Tepavcevic, S.; Zapol, P.; Garcia-Mendez, R.; Taylor, N.J.; Sakamoto, J.; Ingram, B.J.; Curtiss, L.A.; Freeland, J.W.; et al. Dopant-Dependent Stability of Garnet Solid Electrolyte Interfaces with Lithium Metal. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1803440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggestad, K.; Selbach, S.M.; Williamson, B.A. Doping implications of Li solid state electrolyte Li7La3Zr2O12. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 15666–15675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Waluyo, I.; Hunt, A.; Yildiz, B. Avoiding CO2 Improves Thermal Stability at the Interface of Li7La3Zr2O12 Electrolyte with Layered Oxide Cathodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.M.; Chan, C.K. Pyrochlore nanocrystals as versatile quasi-single-source precursors to lithium conducting garnets. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 17405–17410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egaña, A.; Cantelar, E.; Tardío, M.; Santiuste, J.M. Muñoz Santiuste, Synthesis and luminescence properties of Er3+ doped La3NbO7 ceramic powder. Opt. Mater. 2019, 97, 109393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.P.; Gu, W.; Sharma, N.; Peterson, V.K.; Avdeev, M.; Adams, S. In situ neutron diffraction monitoring of Li7La3Zr2O12 formation: Toward a rational synthesis of garnet solid electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 2903–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakiz, B.; Guinneton, F.; Arab, M.; Benlhachemi, A.; Villain, S.; Satre, P.; Gavarri, J.R. Carbonatation and Decarbonatation kinetics in the La2O3-La2O2CO3 system under CO2 gas flows. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2010, 2010, 360597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Kern, F.; Liu, L.; Parr, C.; Börger, A.; Liu, C. Synthesis and Characterization of LLZNO & LLZTO: Insights into the Impact of Different Lithium Precursors on Properties. Open Ceram. 2025, 24, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezabh, H.K.; Abrha, L.H.; Chiu, S.F.; Nikodimos, Y.; Hagos, T.M.; Tsai, M.C.; Su, W.N.; Hwang, B.J. Enhancing ionic conductivity and air stability of Li7La3Zr2O12 garnet-based electrolyte through dual-dopant strategy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.E.; Lewis, T.W.; Meta, M.; Ard, S.G.; Liu, Y.; Sweeny, B.C.; Guo, H.; Ončák, M.; Shuman, N.S.; Meyer, J. Ta+ and Nb+ + CO2: Intersystem crossing in ion–molecule reactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 8670–8680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolella, A.; Zhu, W.; Bertoni, G.; Savoie, S.; Feng, Z.; Demers, H.; Gariepy, V.; Girard, G.; Rivard, E.; Delaporte, N.; et al. Discovering the Influence of Lithium Loss on Garnet Li7La3Zr2O12 Electrolyte Phase Stability. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 3415–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Point for EDS | Composition | Atom Percentage (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La | Zr | Nb | Ta | O | ||

| Spot 1 | La2Zr2O7 | 18.62 | 18.32 | - | - | 63.06 |

| Spot 2 | La3NbO7 | 27.12 | - | 9.06 | - | 63.82 |

| Spot 3 | La3NbO7/La2Zr2O7 | 22.22 | 9.14 | 4.55 | - | 64.09 |

| Spot 4 | La3TaO7/La2Zr2O7 | 21.86 | 9.19 | - | 4.83 | 64.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, C.; Kern, F.; Liu, L.; Parr, C.; Börger, A.; Liu, C. Phase Formation Study of Solid-State LLZNO and LLZTO via Structural, Thermal, and Morphological Analyses. Ceramics 2025, 8, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040132

Li C, Kern F, Liu L, Parr C, Börger A, Liu C. Phase Formation Study of Solid-State LLZNO and LLZTO via Structural, Thermal, and Morphological Analyses. Ceramics. 2025; 8(4):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040132

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Chengjian, Frank Kern, Lianmeng Liu, Christopher Parr, Andreas Börger, and Chunfeng Liu. 2025. "Phase Formation Study of Solid-State LLZNO and LLZTO via Structural, Thermal, and Morphological Analyses" Ceramics 8, no. 4: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040132

APA StyleLi, C., Kern, F., Liu, L., Parr, C., Börger, A., & Liu, C. (2025). Phase Formation Study of Solid-State LLZNO and LLZTO via Structural, Thermal, and Morphological Analyses. Ceramics, 8(4), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040132