Medication Recommendation, Counseling, and Pricing for Nasal Sprays in German Community Pharmacies: A Simulated Patient Investigation

Highlights

- Slightly more than half of the recommended nasal sprays were free of preservatives.

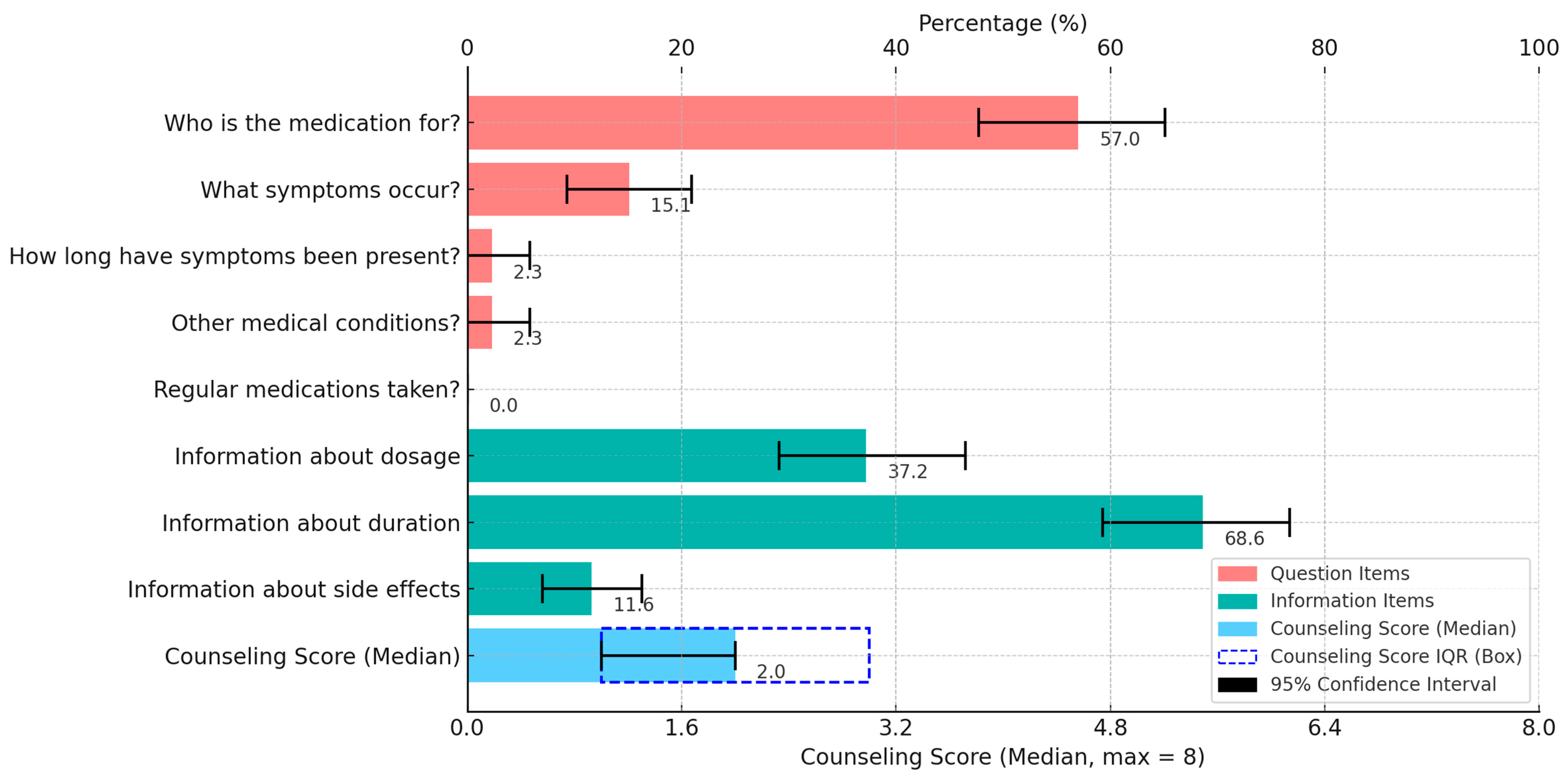

- The median counseling score was 2.0 out of 8 points, with a significantly higher score observed for a female simulated patient.

- Nasal sprays with preservatives were frequently recommended contrary to the medicine guidelines.

- Counseling was poor overall, especially for a male simulated patient.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- which medications are selected (medication recommendation),

- whether questions on information gathering are asked beforehand, and appropriate information is provided on the recommended medications (counseling), and

- the extent to which the costs of the recommended medications differ (pricing).

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Simulated Patients

2.3. Setting and Participation

2.4. Scenario and Assessment

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Management and Analysis

2.7. Ethical Approval

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Medication Recommendation

4.2. Counseling

4.3. Influencing Factors

4.4. Pricing

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Upper Respiratory Infections Otitis Media Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of upper respiratory infections and otitis media, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guibas, G.V.; Papadopoulos, N.G. Viral Upper Respiratory Tract Infections. In Viral Infections in Children Volume II; Green, R.J., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, B.; Kumar, M.P.; Pavithra, N.; Praveen, R.; Komal, S.; Harikrisnan, N. Upper respiratory tract infections and treatment: A short review. Neuroquantology 2023, 21, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Grief, S.N. Upper respiratory infections. Prim. Care 2013, 40, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I.; et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020, 58 (Suppl. S29), 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, R.R.; Kingdom, T.T.; Smith, T.L.; Bleier, B.; DeConde, A.; Luong, A.U.; Poetker, D.M.; Soler, Z.; Welch, K.C.; Wiseet, S.K.; et al. International consensus statement on allergy and rhinology: Rhinosinusitis 2021. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021, 11, 213–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, D.L.; Lucas, J.W.; Clarke, T.C. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National health interview survey. Vital Health Stat. 2014, 260, 1–161. [Google Scholar]

- Witek, T.J.; Ramsey, D.L.; Carr, A.N.; Riker, D.K. The natural history of community-acquired common colds symptoms assessed over 4-years. Rhinology 2015, 53, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuck, B.A.; Beule, A.; Jobst, D.; Klimek, L.; Laudien, M.; Lell, M.; Vogl, T.J.; Popert, U. Guideline for “rhinosinusitis”-long version: S2k guideline of the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians and the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. HNO 2018, 66, 38–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petković, S.; Maletić, I.; Đurić, S.; Dragutinović, N.; Milovanović, O. Evaluation of nasal decongestants by literature review. Ser. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2024, 25, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karra, G.; Kiran, R.S.; Mardanapall, S.; Rao, T.R. A review on challenges in developing nasal sprays. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 2022, 13, 07–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematian-Samani, M.; Mösges, R. Rhinitis—causes, complications, therapy. MMW Fortschr. Med. 2014, 156, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsche, T.; Alexa, J.A.; Eickhoff, C.; Schulz, M. Self-care and self-medication as central components of healthcare in Germany—on the way to evidence-based pharmacy. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2023, 9, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ApBetrO. Apothekenbetriebsordnung in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 26. September 1995 (BGBl. I S. 1195), die zuletzt durch Artikel 8z4 des Gesetzes vom 12. Dezember 2023 (BGBl. 2023 I Nr. 359) geändert worden ist. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/apobetro_1987/ApBetrO.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- BAK—Federal Chamber of Pharmacists. Information und Beratung im Rahmen der Selbstmedikation am Beispiel Schnupfen. Stand der Revision: 28 November 2023. Available online: https://www.abda.de/fileadmin/user_upload/assets/Praktische_Hilfen/Leitlinien/Selbstmedikation/AWB_SM_Schnupfen.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- BAK—Federal Chamber of Pharmacists. Arzneimittelmissbrauch Leitfaden für die apothekerliche Praxis. 2018. Available online: https://www.abda.de/fileadmin/user_upload/assets/Arzneimittelmissbrauch/BAK_Leitfaden_Arzneimittelmissbrauch.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- IQVIA Commercial. IQVIA Marktbericht 2020. Entwicklung des deutschen Pharmamarktes im Jahr 2019. Available online: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/cese/germany/publikationen/marktbericht/pharma-marktbericht-jahr-2019-iqvia-0220.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Peabody, J.W.; Luck, J.; Glassman, P.; Dresselhaus, T.R.; Lee, M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: A prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA 2000, 283, 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.C.; Chong, W.W.; de Almeida Neto, A.C.; Moles, R.J.; Schneider, C.R. The simulated patient method: Design and application in health services research. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 2108–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunow, C.; Langer, B. Simulated patient methodology as a “gold standard” in community pharmacy practice: Response to criticism. World J. Methodol. 2024, 14, 93026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björnsdottir, I.; Granas, A.G.; Bradley, A.; Norris, P. A systematic review of the use of simulated patient methodology in pharmacy practice research from 2006 to 2016. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 28, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, F.A. Covert and Overt Observations in Pharmacy Practice. In Pharmacy Practice Research Methods; Babar, Z.U.D., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; de Almeida Neto, A.C.; Moles, R.J. A systematic review of simulated-patient methods used in community pharmacy to assess the provision of non-prescription medicines. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2012, 20, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neoh, C.F.; Hassali, M.A.; Shafie, A.A.; Awaisu, A.; Tambyappa, J. Compliance towards dispensed medication labelling standards: A cross-sectional study in the state of Penang, Malaysia. Curr. Drug Saf. 2009, 4, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neoh, C.F.; Hassali, M.A.; Shafie, A.A.; Awaisu, A. Nature and adequacy of information on dispensed medications delivered to patients in community pharmacies: A pilot study from Penang, Malaysia. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 2, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabid, A.H.M.A.; Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Hassali, M.A. Do Professional Practices among Malaysian Private Healthcare Providers Differ? A Comparative Study using Simulated Patients. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 2912–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabid, A.H.M.A.; Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Hassali, M.A. Dispensing Practices of General Practitioners and Community Pharmacists in Malaysia–A Pilot Study. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2013, 43, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabid, A.H.M.A.; Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Hassali, M.A. Antibiotics Dispensing for URTIs by Community Pharmacists (CPs) and General Medical Practitioners in Penang, Malaysia: A Comparative Study using Simulated Patients (SPs). J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhael, E.M. Evaluating the Rationality of Antibiotic Dispensing in Treating Common Cold Infections among Pharmacists in Baghdad—Iraq 2014. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2014, 4, 2653–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atia, A.E.; Abired, A.N. Antibiotic Prescribing for Upper Respiratory Tract Infections by Libyan Community Pharmacists and Medical Practitioners: An Observational Study. Libyan J. Med. Sci. 2017, 1, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Awaisu, A.; Palaian, S.; Radoui, A.; Atwa, H. Do community pharmacists in Qatar manage acute respiratory conditions rationally? A simulated client study. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 2018, 9, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, A.I.; Tawfik, A.G.; Rabie, K.A.; Omran, M.; Hussein, M.; Abou-Ali, A.; Ahmed, A.F. Quality of Community Pharmacy Practice in Antibiotic Self-Medication Encounters: A Simulated Patient Study in Upper Egypt. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koji, E.M.; Gebretekle, G.B.; Tekle, T.A. Practice of over-the-counter dispensary of antibiotics for childhood illnesses in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A simulated patient encounter study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minarikova, D.; Fazekaš, T.; Minárik, P.; Jurišová, E. Assessment of patient counselling on the common cold treatment at Slovak community pharmacies using mystery shopping. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafade, V.; Huddart, S.; Sulis, G.; Daftary, A.; Miraj, S.S.; Saravu, K.; Pai, M. Over-the-counter antibiotic dispensing by pharmacies: A standardised patient study in Udupi district, India. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawahir, S.; Lekamwasam, S.; Aslani, P. Community pharmacy staff’s response to symptoms of common infections: A pseudo-patient study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloudah, N.; Alhumsi, A.; Alobeid, N.; Aboheimed, N.; Aboheimed, H.; Aboheimed, G. Factors impeding the supply of over-the-counter medications according to evidence-based practice: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atia, A. Information provided to customers about over-the-counter medications dispensed in community pharmacies in Libya: A crosssectional study. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020, 26, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneemai, O.; Jaipinta, T.; Rattanatanyapat, P. Evaluation of Community Pharmacy Personnel in Pharmaceutical Services Using the Simulated Patient. Thai Bull. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 15, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Palaian, S.; Al Omar, M.; Hassan, N.; Mourad, D.; Ahmed, W.; Ewida, A. Community pharmacy practice evaluation in the United Arab Emirates using simulated patients with common cold. Special Issue: Abstracts of the 36th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management, Virtual, 16–17 September 2020. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2020, 29 (Suppl 3), 197–198. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Chang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhai, P.; Hu, S.; Li, P.; Hayat, K.; Kabba, J.A.; Feng, Z.; Yang, C.; et al. Dispensing Antibiotics without a Prescription for Acute Cough Associated with Common Cold at Community Pharmacies in Shenyang, Northeastern China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, R.M.; Udoh, E.I.; Akpan, S.E.; Ozuluoha, C.C. Community pharmacists’ management of self-limiting infections: A simulation study in Akwa Ibom State, South-South Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, R.A.; Farha, R.A.; Al Ali, M.M.; Jaradaneh, N.S.; Ibrahim, M.I.M. Evaluation of Community Pharmacists’ Professional Practice and Management of Patient’s Respiratory Conditions. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belachew, S.A.; Hall, L.; Selvey, L.A. Magnitude of non-prescribed antibiotic dispensing in Ethiopia: A multicentre simulated client study with a focus on non-urban towns. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 3462–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseno, M.; Widyastiwi, W. Assessing Quality of Self-Medication Services in Pharmacies in Bandung, West Java, Indonesia using a Mystery Customer Approach. Indones. J. Pharm. 2023, 34, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puumalainen, I.I.; Peura, S.H.; Kansanaho, H.M.; Benrimoj, C.S.I.; Airaksinen, M.S.A. Progress in patient counselling practices in Finnish community pharmacies. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2005, 13, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alastalo, N.; Siitonen, P.; Jyrkkä, J.; Hämeen-Anttila, K. The quality of non-prescription medicine counselling in Finnish pharmacies—A simulated patient study. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2023, 11, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunow, C.; Langer, B. Using the simulated patient methodology to assess the quality of counselling in german community pharmacies: A systematic review from 2005 to 2018. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 13, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, B.; Kunow, C. Medication dispensing, additional therapeutic recommendations, and pricing practices for acute diarrhoea by community pharmacies in Germany: A simulated patient study. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 17, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, B.; Kunow, C. Do north-eastern German pharmacies recommend a necessary medical consultation for acute diarrhoea? Magnitude and determinants using a simulated patient approach [version 2; peer review: 3 approved]. F1000Research 2020, 8, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, B.; Grimm, S.; Lungfiel, G.; Mandlmeier, F.; Wenig, V. The Quality of Counselling for Oral Emergency Contraceptive Pills—A Simulated Patient Study in German Community Pharmacies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, B.; Kunow, C. The Quality of Counseling for Headache OTC Medications in German Community Pharmacies Using a Simulated Patient Approach: Are There Differences between Self-Purchase and Purchase for a Third Party? Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 5851117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lungfiel, G.; Mandlmeier, F.; Kunow, C.; Langer, B. Oral emergency contraception practices of community pharmacies: A mystery caller study in the capital of Germany, Berlin. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2023, 16, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, B.; Kunow, C.; Bolduan, J.; Sackmann, L.; Schreiter, L.; Schüler, K.; Ulrich, M. Counselling with a focus on product and price transparency for over-the-counter headache medicines: A simulated patient study in community pharmacies in Munich, Germany. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2024, 39, 1434–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation/World Health Organization (FIP/WHO). Good Pharmacy Practice. Joint FIP/WHO Guidelines on GPP: Standards for Quality of Pharmacy Services. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 961, Annex 8. 2011. Available online: https://www.fip.org/files/fip/WHO/GPP%20guidelines%20FIP%20publication_final.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Kunow, C.; Langer, B. Dispensing and Variabilities in Pricing of Headache OTC Medicines by Community Pharmacies in a German Big City: A Simulated Patient Approach. Clinicoecon. Outcomes Res. 2021, 13, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.S.; Hatah, E.; Jalil, M.R.; Makmor-Bakry, M. Consumers’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Toward Medicine Price Transparency at Private Healthcare Setting in Malaysia. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 589734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher Bundestag. Unterrichtung durch die Bundesregierung. Achtzehntes Hauptgutachten der Monopolkommission 2008/2009. 2010. Available online: https://www.monopolkommission.de/images/PDF/HG/HG18/1702600.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- PAngV. Preisangabenverordnung vom 12. November 2021 (BGBl. I S. 4921). Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/pangv_2022/PAngV.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Arora, S.; Sood, N.; Terp, S.; Joyce, G. The price may not be right: The value of comparison shopping for prescription drugs. Am. J. Manag. Care 2017, 23, 410–415. [Google Scholar]

- Vogler, S.; Paterson, K.R. Can Price Transparency Contribute to More Affordable Patient Access to Medicines? Pharmacoecon. Open 2017, 1, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, B.; Bull, E.; Burgsthaler, T.; Glawe, J.; Schwobeda, M.; Simon, K. Using the simulated patient methodology to assess counselling for acute Diarrhoea—Evidence from Germany. Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes. 2016, 112, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- STROBE Statement. Checklist of Items That Should Be Included in Reports of Cross-Sectional Studies. Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_cross-sectional.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Cheng, A.; Kessler, D.; Mackinnon, R.; Chang, T.P.; Nadkarni, V.M.; Hunt, E.A.; Duval-Arnould, J.; Lin, Y.; Cook, D.A.; Pusic, M.; et al. Reporting guidelines for health care simulation research: Extensions to the CONSORT and STROBE statements. Simul. Healthc. 2016, 11, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Page, A.; Clifford, R.; Bond, C.; Seubert, L. Refining the CRiSPHe (checklist for reporting research using a simulated patient methodology in Health): A Delphi study. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2024, 32, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeshauptstadt Schwerin. Statistisches Jahrbuch 2021. Available online: https://www.schwerin.de/export/sites/default/.galleries/Dokumente/Stadtportraet/Statistisches_Jahrbuch_2021.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Stadt Neubrandenburg. Statistisches Jahrbuch 2024. Available online: https://neubrandenburg.de/media/custom/3330_3225_1.PDF?1734609098 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Statistisches Amt Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Statistisches Jahrbuch Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 2021. Available online: https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/MVHeft_derivate_00006074/Z011%202021%2000.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Apotheken Umschau. Apothekensuche: Finden Sie Apotheken in Ihrer Nähe. Available online: https://www.apotheken-umschau.de/apothekenfinder/ (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Bosnic-Anticevich, S.; Costa, E.; Menditto, E.; Lourenço, O.; Novellino, E.; Bialek, S.; Briedis, V.; Buonaiuto, R.; Chrystyn, H.; Cvetkovski, B.; et al. ARIA pharmacy 2018 “Allergic rhinitis care pathways for community pharmacy”: AIRWAYS ICPs initiative (European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing, DG CONNECT and DG Santé) POLLAR (Impact of Air POLLution on Asthma and Rhinitis) GARD Demonstration project. Allergy 2019, 74, 1219–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, O.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S.; Costa, E.; Fonseca, J.A.; Menditto, E.; Cvetkovski, B.; Kritikos, V.; Tan, R.; Bedbrook, A.; Scheire, S.; et al. Managing Allergic Rhinitis in the Pharmacy: An ARIA Guide for Implementation in Practice. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, J.; Onorato, G.L.; Jutel, M.; Akdis, C.A.; Agache, I.; Zuberbier, T.; Czarlewski, W.; Mullol, J.; Bedbrook, A.; Bachert, C.; et al. Differentiation of COVID-19 signs and symptoms from allergic rhinitis and common cold: An ARIA-EAACI-GA2 LEN consensus. Allergy 2021, 76, 2354–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashour, T.S.; Joury, A.; Alotaibi, A.M.; Althagafi, M.; Almufleh, A.S.; Hersi, A.; Thalib, L. Quality of assessment and counseling offered by community pharmacists and medication sale without prescription to patients presenting with acute cardiac symptoms: A simulated client study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 72, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kippist, C.; Wong, K.; Bartlett, D.; Saini, B. How do pharmacists respond to complaints of acute insomnia? A simulated patient study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2011, 33, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, M.; Diep, J.; Bittoun, R.; Saini, B. Provision of smoking cessation services in Australian community pharmacies: A simulated patient study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2014, 36, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.C.; Schneider, C.R.; Naughtin, C.L.; Wilson, F.; de Almeida Neto, A.C.; Moles, R.J. Mystery shopping and coaching as a form of audit and feedback to improve community pharmacy management of non-prescription medicine requests: An intervention study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e019462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paravattil, B.; Kheir, N.; Yousif, A. Utilization of simulated patients to assess diabetes and asthma counseling practices among community pharmacists in Qatar. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojah, H.M.J. Over-the-counter sale of antibiotics during COVID-19 outbreak by community pharmacies in Saudi Arabia: A simulated client study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BBK—Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe. COVID-19: Übersicht Kritischer Dienstleistungen. Sektorspezifische Hinweise und Informationen mit KRITIS-Relevanz. 2021. Available online: https://ms.sachsen-anhalt.de/fileadmin/Bibliothek/Politik_und_Verwaltung/MS/MS/3_Menschen_mit_Behinderungen_2015/covid-19-uebersicht-kritische-dienstleistungen.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ruxton, G.D.; Neuhäuser, M. Good practice in testing for an association in contingency tables. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2010, 64, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BVM. Berufsverband Deutscher Markt-und Sozialforscher e.V. Richtlinie für den Einsatz von Mystery Research in der Markt- und Sozialforschung. 2022. Available online: https://www.bvm.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Verbandsdokumente/Standesregeln_RL_neu_2021/Richtlinie_fuer_den_Einsatz_von_Mystery_Research_2022.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Choi, W.; Jung, J.J.; Grantcharov, T. Impact of Hawthorne effect on healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Univ. Tor. Med. J. 2019, 96, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, K.V.; Miller, F.G. Simulated patient studies: An ethical analysis. Milbank Q. 2012, 90, 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobark, D.M.; Al-Tabakha, M.M.; Hasan, S. Assessing hormonal contraceptive dispensing and counseling provided by community pharmacists in the United Arab Emirates: A simulated patient study. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 17, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, C.E.; Bispo, M.L.; dos Santos, A.C.O.; Mesquita, A.; Brito, G.C.; de Lyra, D.P. Assessment of Community Pharmacists’ Counseling Practices with Simulated Patients Who Have Minor Illness. Simul. Health J. Soc. Simul. Health 2015, 10, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayshap, K.C.; Nissen, L.M.; Smith, S.S.; Kyle, G. Management of over-the-counter insomnia complaints in Australian community pharmacies: A standardised patient study. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2014, 22, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-C.; Park, W.-J.; Oh, M.-K. Prescription Pattern for a Simulated Patient With the Common Cold at Pharmacies in a Region in Korea Without Separation of Dispensary From Medical Practice. Korean J. Health Serv. Manag. 2019, 13, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, B.; Theis, H.-J. OTC-Studie 2015. Empfehlungsverhalten in Apotheken. Pharm. Ztg. 2016, 161, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Halme, M.; Linden, K.; Kääriä, K. Patients’ Preferences for Generic and Branded Over-the-Counter Medicines: An Adaptive Conjoint Analysis Approach. Patient 2009, 2, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, M. Medicine prices in European countries. In Medicine Price Surveys, Analyses and Comparisons. Evidence and Methodology Guidance; Vogler, S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, S.N.; Lotfi, F.; Hadian, M.; Safari, H.; Rezapour, A. Factors influencing pharmaceutical Demand in Iran: Results from a regression study. Int. J. Hosp. Res. 2014, 3, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer Taxe. LTO4.0. 2025. Available online: https://www.cgm.com/deu_de/produkte/apotheke/lauer-taxe.html (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Langer, B.; Bull, E.; Burgsthaler, T.; Glawe, J.; Schwobeda, M.; Simon, K. Assessment of counselling for acute diarrhoea in German pharmacies: A simulated patient study. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 26, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, B.; Kieper, M.; Laube, S.; Schramm, J.; Weber, S.; Werwath, A. Assessment of counselling for acute diarrhoea in North-Eastern German pharmacies—A follow-up study using the simulated patient methodology. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2018, 9, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisman, C.S.; Teitelbaum, M.A. Women and health care communication. Patient Educ. Couns. 1989, 13, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisman, C.S. Communication between women and their health care providers: Research findings and unanswered questions. Public Health Rep. 1987, 102 (Suppl. 4), 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbard-Alley, A.S. Health Communication and Gender: A Review and Critique. Health Commun. 1995, 7, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, R.L., Jr. Gender differences in health care provider-patient communication: Are they due to style, stereotypes, or accommodation? Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 48, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, D.; Berens, E.-M.; Vogt, D. Health Literacy in the German Population. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, D.; Berens, E.-M.; Vogt, D.; Gille, S.; Griese, L.; Klinger, J.; Hurrelmann, K. Health Literacy in Germany—Findings of a Representative Follow-up Survey. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2021, 118, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraverty, D.; Baumeister, A.; Aldin, A.; Seven, Ü.S.; Monsef, I.; Skoetz, N.; Woopen, C.; Kalbe, E. Gender differences of health literacy in persons with a migration background: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliffe, J.L.; Rossnagel, E.; Kelly, M.T.; Bottorff, J.L.; Seaton, C.; Darroch, F. Men’s health literacy: A review and recommendations. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Cachafeiro, M.; Piñeiro-Lamas, M.; Guinovart, M.C.; López-Vázquez, P.; Vázquez-Lago, J.M.; Figueiras, A. Magnitude and determinants of antibiotic dispensing without prescription in Spain: A simulated patient study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.; Whyte, S.; Chan, H.F.; Kyle, G.; Lau, E.T.L.; Nissen, L.M.; Torgler, B.; Dulleck, U. Pharmacist Compliance With Therapeutic Guidelines on Diagnosis and Treatment Provision. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e197168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.C.; Schneider, C.R.; Moles, R.J. Emergency contraception supply in Australian pharmacies after the introduction of ulipristal acetate: A mystery shopping mixed-methods study. Contraception 2018, 98, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, S.S.; Ramachandran, C.D.; Paraidathathu, T.T. Response of Community Pharmacists to the Presentation of Back Pain: A Simulated Patient Study. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2010, 14, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.R.; Palaian, S.; Ibrahim, M.I. Assessment of diarrhea treatment and counseling in community pharmacies in Baghdad, Iraq: A simulated patient study. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 16, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, J.H.; Mbadu, M.F.; Garcia, M.; Glover, A. The provision of emergency contraception in Kinshasa’s private sector pharmacies: Experiences of mystery clients. Contraception 2018, 97, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunenberg, M.; Bäumler, M. Zurück in die Zukunft: Zur Modernisierung der Arzneimittelversorgung durch Apotheken. Gesundh. Sozialpolitik 2021, 75, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.I.; Chaar, R.J.; Albadrani, Z.Z.; Shahwan, J.S.; Badreddin, M.N.; Charbaji, M.A.K. Evaluation of the knowledge and perceptions of patients towards generic medicines in UAE. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2016, 7, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogler, S.; Österle, A.; Mayer, S. Inequalities in medicine use in Central Eastern Europe: An empirical investigation of socioeconomic determinants in eight countries. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher Bundestag. Bericht über die Ergebnisse der Arbeit der Markttransparenzstelle für Kraftstoffe und die Hieraus Gewonnenen Erfahrungen. 2018. Available online: https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Publikation/DE/Berichte/Evaluierungsbericht_MTS-K_.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Griffith University. Final Assessment of the Queensland Fuel Price Reporting Trial for the Department of Energy and Public Works. 2021. DNRME 03/07/3795. 2021. Available online: https://www.epw.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/18340/final-fuel-price-reporting-trial.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Bundeskartellamt. Market Transparency Unit for Fuels. Available online: https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/EN/Tasks/markettransparencyunit_fuels/markettransparencyunit_fuels_node.html#:~:text=The%20Market%20Transparency%20Unit%20for,current%20fuel%20prices%20in%20Germany.&text=The%20price%20data%20collected%20by,forms%20of%20market%20power%20abuse (accessed on 31 January 2025).

| The SP entered the CP and said at the beginning of the conversation: “Hello, a nasal spray, please.” The SP did not have a particular product in mind. When questioned by the pharmacy staff, the following information was provided by the SP: | |

| Possible questions on information gathering asked by the pharmacy staff | Information given by the SP |

| Who is the medication for? | For me |

| What symptoms occur? | Nasal congestion |

| How long have the symptoms been present? | For three days |

| Are there other medical conditions? | No other medical conditions |

| Which medications are taken regularly? | No medications |

| YES | NO | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| ||

| 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| Name | |

| Price (EUR) | |

| Possible Influencing Factors [Literature Sources *] | Time of Data Collection | Type of Data Collection |

|---|---|---|

| City of the CPs [74] | Before the visit | Exact measurement by assigning the CPs determined for the respective cities |

| CP quality certificate [75] | After the visit | Exact measurement using a telephone query by the SPs after completing all the visits |

| Age of the pharmacy staff [76] | During the visit | Estimate using a visual impression of the SP |

| Gender of the pharmacy staff [76] | During the visit | Exact measurement using a visual impression of the SP |

| Professional group of the pharmacy staff [77] | During and after the visit | Exact measurement based on the name tag and, if necessary, using a telephone query by the SP after completing all the visits |

| Gender of the SPs [78] | Before the visit | Exact measurement based on the gender of the SP |

| Time of the visit [74] | During the visit | Exact measurement using the SP’s watch |

| Queue—customers waiting behind the SP [57] | During the visit | Exact measurement using a visual impression of the SP |

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| All CPs | 86 | 100.0 |

| City of the CPs | ||

| 50 | 58.1 |

| 36 | 41.9 |

| CP quality certificate | ||

| 31 | 36.1 |

| 55 | 63.9 |

| Age of the pharmacy staff | ||

| 10 | 11.6 |

| 53 | 61.6 |

| 23 | 26.8 |

| Gender of the pharmacy staff | ||

| 12 | 14.0 |

| 74 | 86.0 |

| Professional group of the pharmacy staff | ||

| 21 | 24.4 |

| 46 | 53.5 |

| 19 | 22.1 |

| Gender of the SPs | ||

| 43 | 50.0 |

| 43 | 50.0 |

| Time of the visit | ||

| 37 | 43.0 |

| 26 | 30.2 |

| 23 | 26.8 |

| Queue—customers waiting behind the SP | ||

| 65 | 75.6 |

| 21 | 24.4 |

| City of the CPs | CP Quality Certificate | Age of the Pharmacy Staff | Gender of the Pharmacy Staff | Professional Group of the Pharmacy Staff | Gender of the SP | Time of the Visit | Queue—Customers Waiting Behind the SP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication recommendation | c 0.637 (0.075) | c 0.292 (0.170) | b 0.185 (0.167) | c 1.000 (0.089) | b 1.000 (0.017) | c 0.116 (0.221) | b 0.812 (0.100) | c 0.249 (0.132) |

| Who is the medication for? | a 0.124 (0.166) | a 0.729 (0.037) | b 0.161 (0.207) | a 0.248 (0.125) | a 0.258 (0.177) | a 0.001 * (0.352) | a 0.433 (0.139) | a 0.986 (0.002) |

| What symptoms occur? | a 0.342 (0.103) | c 0.540 (0.078) | b 0.012 * (0.332) | c 0.683 (0.076) | b 0.790 (0.069) | a 0.366 (0.097) | b 0.599 (0.106) | c 0.507 (0.089) |

| How long have the symptoms been present? | c 1.000 (0.025) | c 1.000 (0.041) | b 0.144 (0.255) | c 1.000 (0.062) | b 1.000 (0.144) | c 0.494 (0.154) | b 0.737 (0.111) | c 1.000 (0.088) |

| Are there other medical conditions? | c 0.172 (0.182) | c 0.999 (0.041) | b 1.000 (0.122) | c 0.261 (0.161) | b 0.717 (0.108) | c 0.494 (0.154) | b 0.504 (0.178) | c 1.000 (0.088) |

| Information about dosage | a 0.858 (0.019) | a 0.676 (0.045) | b 1.000 (0.034) | c 0.350 (0.107) | a 0.254 (0.179) | a 0.074 (0.192) | a 0.714 (0.089) | a 0.923 (0.010) |

| Information about duration | a 0.887 (0.015) | a 0.615 (0.054) | b 1.000 (0.019) | c 0.505 (0.089) | a 0.249 (0.180) | a 0.104 (0.175) | a 0.534 (0.121) | a 0.193 (0.140) |

| Information about side effects | c 0.510 (0.087) | c 1.000 (0.021) | b 0.552 (0.106) | c 1.000 (0.041) | b 0.396 (0.149) | a 0.007 * (0.290) | b 0.104 (0.219) | c 0.701 (0.047) |

| Counseling score | d 0.403 (0.090) | d 0.739 (0.036) | e 0.409 | d 0.500 (0.073) | e 0.228 | d 0.004 * (0.306) | e 0.947 | d 0.485 (0.075) |

| Price | d 0.888 (0.015) | d 0.816 (0.025) | e 0.438 | d 0.446 (0.082) | e 0.758 | d 0.494 (0.074) | e 0.908 | d 0.832 (0.023) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Polish Respiratory Society. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Langer, B.; Kunow, C.; Dethloff, T.; George, S. Medication Recommendation, Counseling, and Pricing for Nasal Sprays in German Community Pharmacies: A Simulated Patient Investigation. Adv. Respir. Med. 2025, 93, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93030018

Langer B, Kunow C, Dethloff T, George S. Medication Recommendation, Counseling, and Pricing for Nasal Sprays in German Community Pharmacies: A Simulated Patient Investigation. Advances in Respiratory Medicine. 2025; 93(3):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93030018

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanger, Bernhard, Christian Kunow, Tim Dethloff, and Sarah George. 2025. "Medication Recommendation, Counseling, and Pricing for Nasal Sprays in German Community Pharmacies: A Simulated Patient Investigation" Advances in Respiratory Medicine 93, no. 3: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93030018

APA StyleLanger, B., Kunow, C., Dethloff, T., & George, S. (2025). Medication Recommendation, Counseling, and Pricing for Nasal Sprays in German Community Pharmacies: A Simulated Patient Investigation. Advances in Respiratory Medicine, 93(3), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93030018