Influence of Shungite from the Bakyrchik Deposit on the Properties of Rubber Composites Based on a Blend of Non-Polar Diene Rubbers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Rubber Compounds and Vulcanizates

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. SEM-EDS

2.3.2. Determination of the Elemental Composition of Shungite Materials

2.3.3. Determination of the Specific Surface Area of Fillers

2.3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

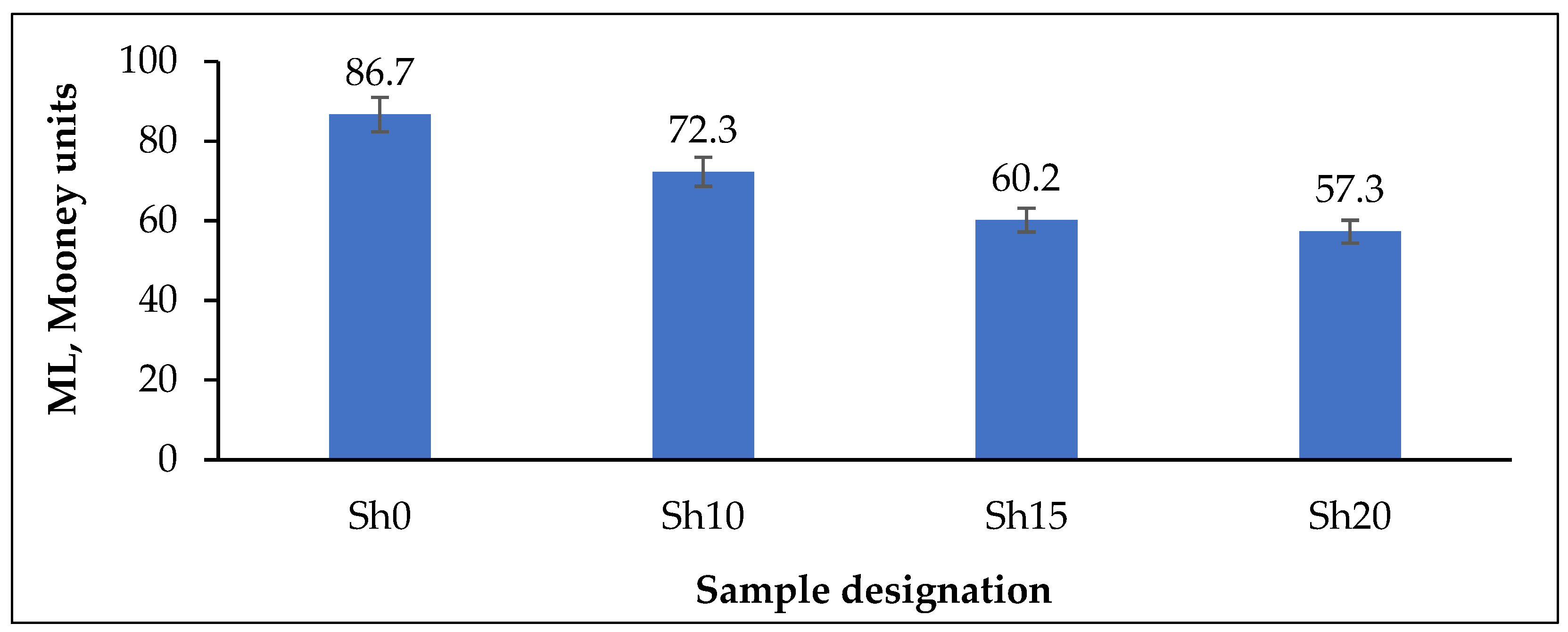

2.3.5. Determination of Mooney Viscosity

2.3.6. Studying the Kinetics of Vulcanization

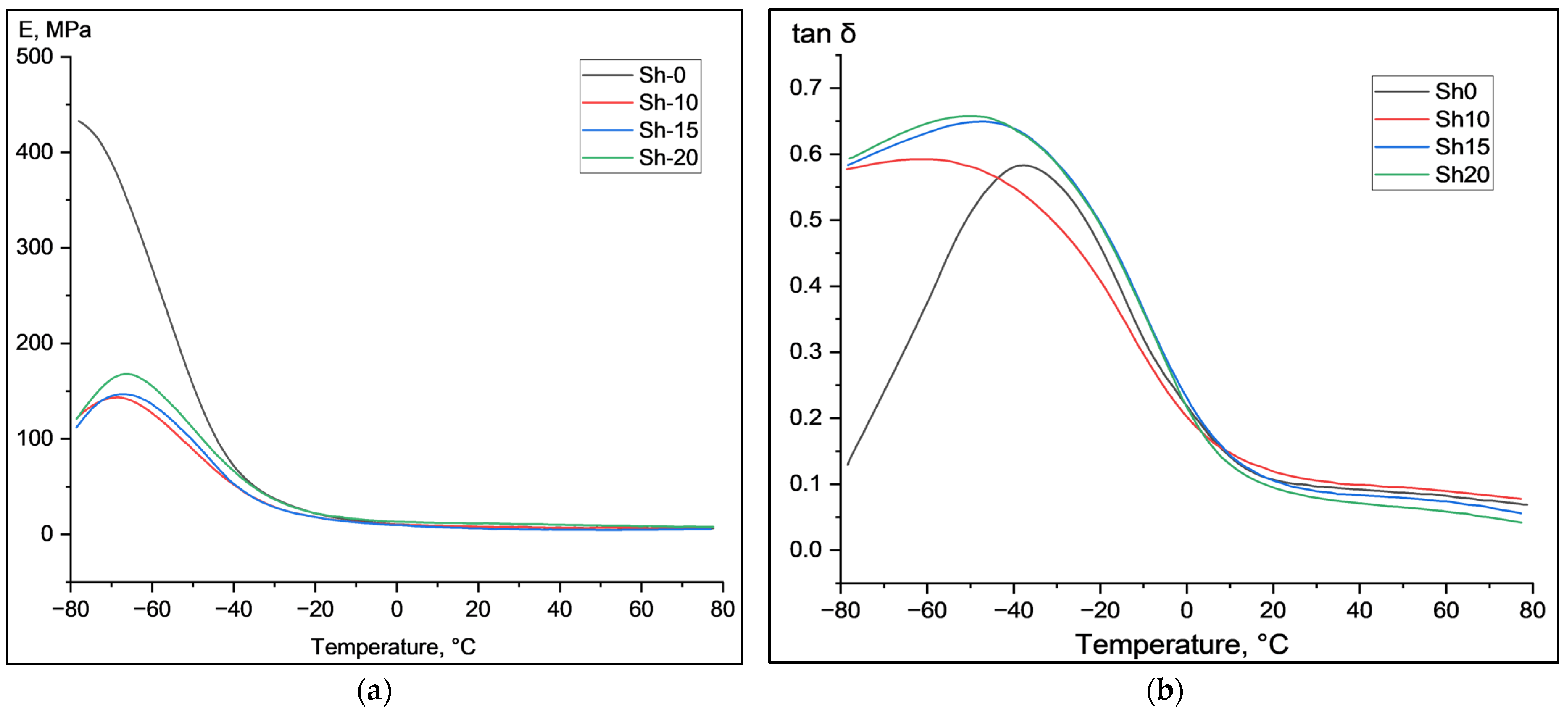

2.3.7. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

2.3.8. Physicomechanical Properties and Thermal Aging Resistance of Rubbers

2.3.9. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

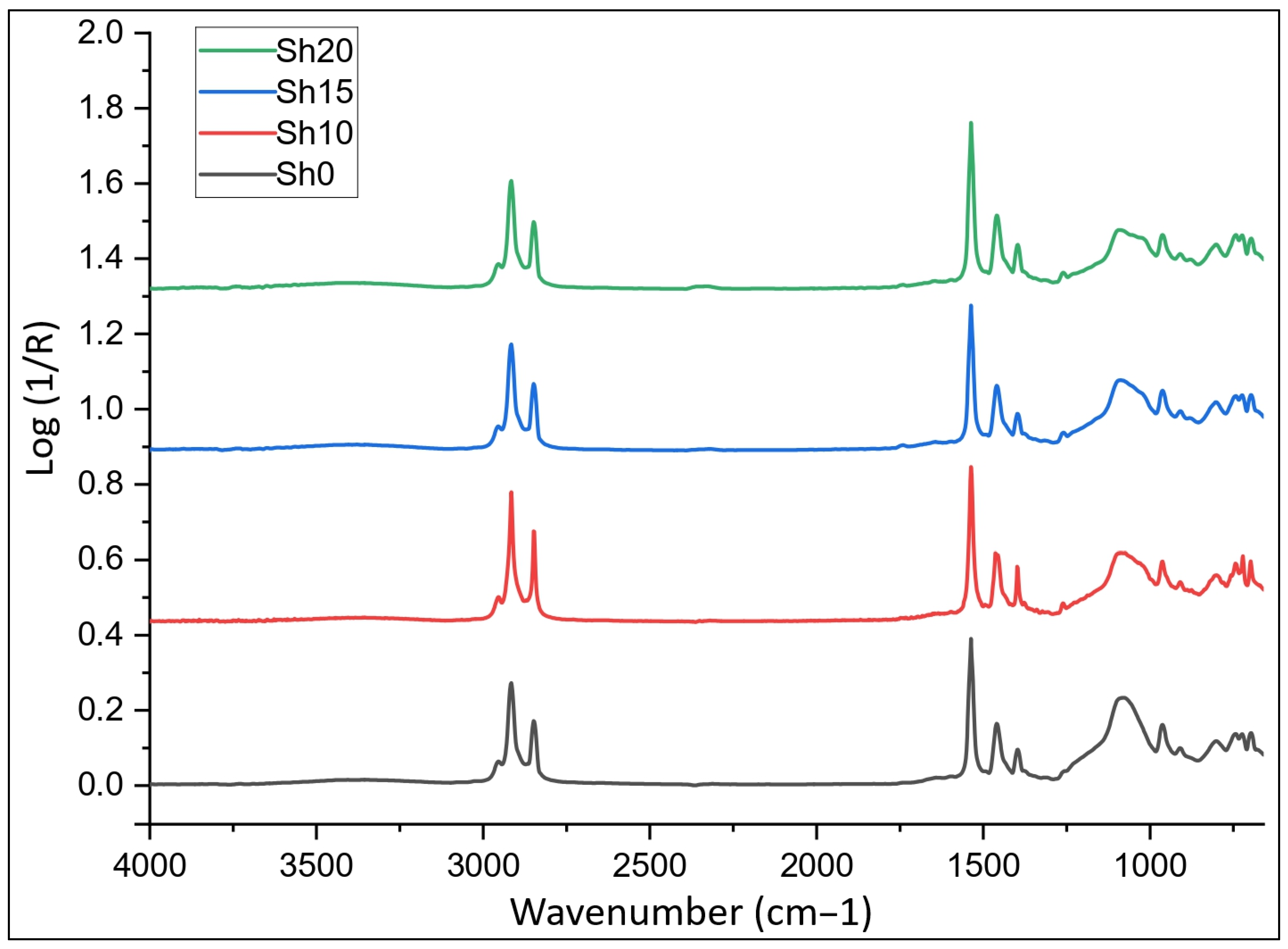

2.3.10. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

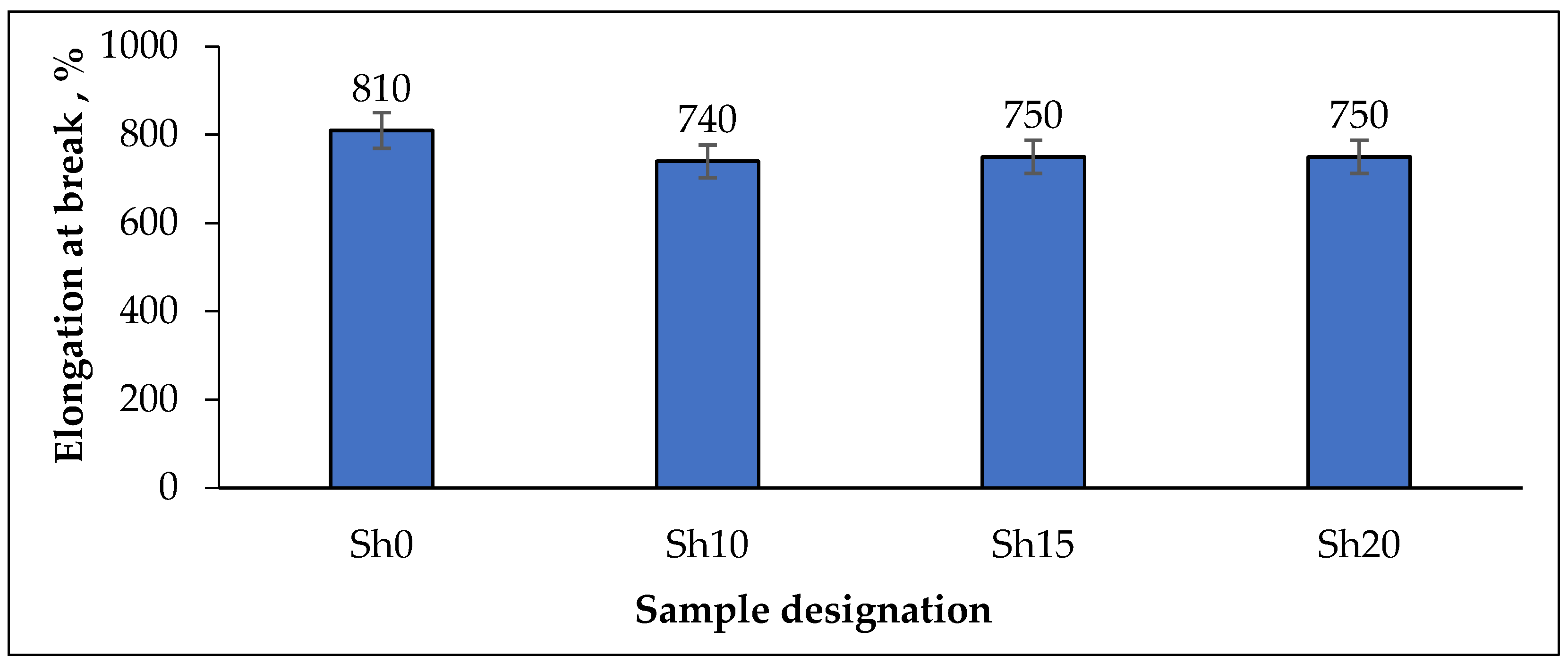

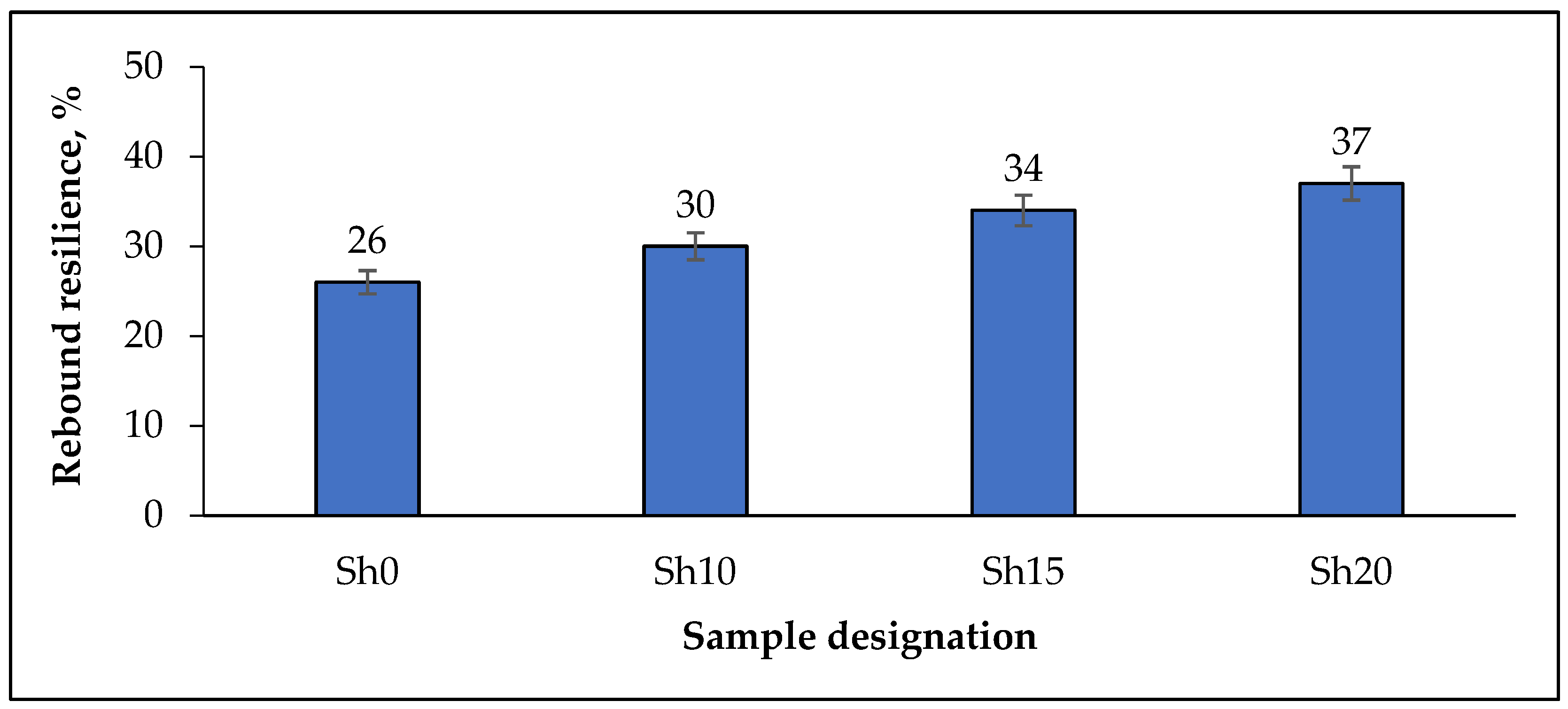

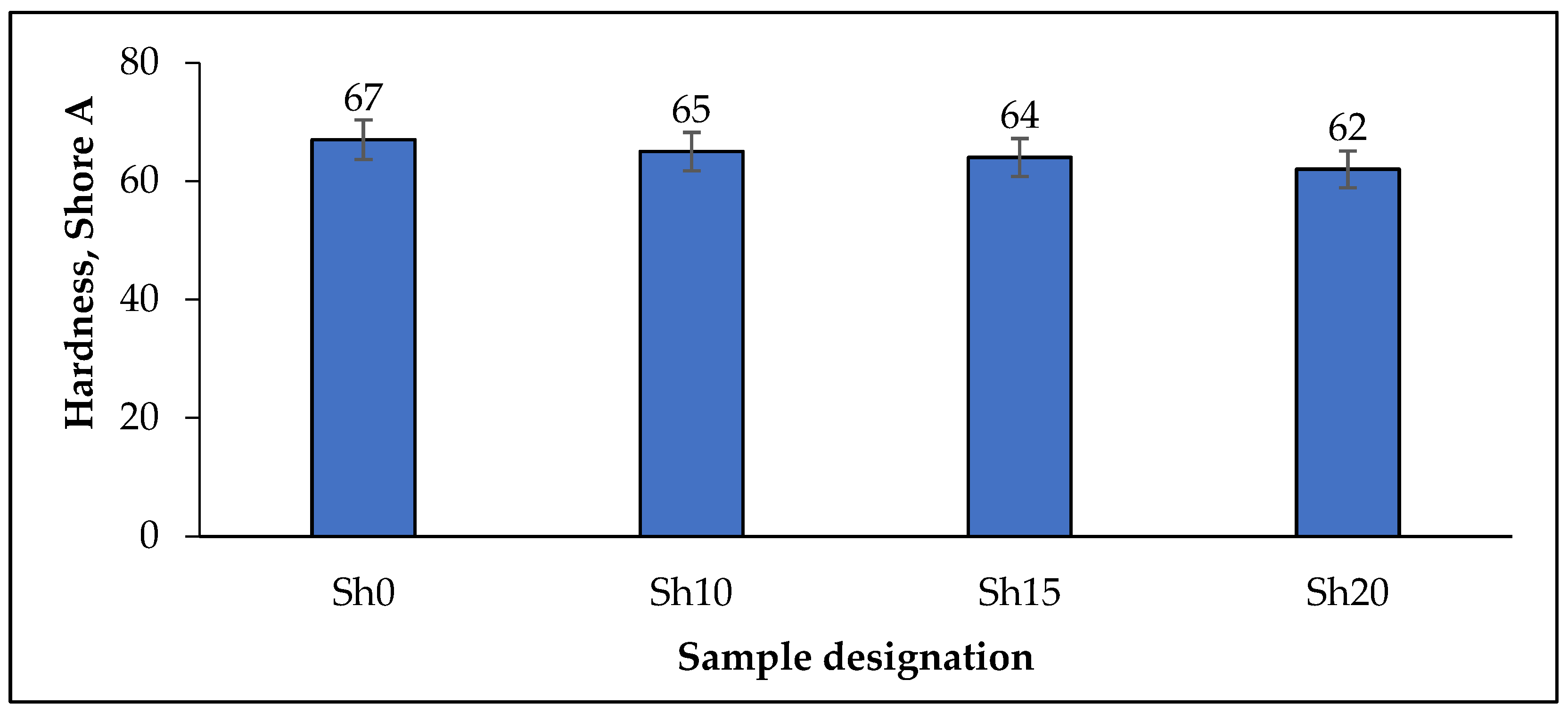

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IR SKI-3 | Synthetic isoprene rubber |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SBR | butadiene-alpha-methylstyrene rubber |

| ShO | Shungite ore |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

References

- Dadkhah, M.; Messori, M. A Comprehensive Overview of Conventional and Bio-Based Fillers for Rubber Formulations Sustainability. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Fowler, G.D.; Zhao, M. The Past, Present and Future of Carbon Black as a Rubber Reinforcing Filler–A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.G.; Hardman, N.J. Nature of Carbon Black Reinforcement of Rubber: Perspective on the Original Polymer Nanocomposite. Polymers 2021, 13, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, G.R.; Al-Sheneper, A.A. Effect of Carbon Black Concentration on Cut Growth in NR Vulcanizates. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2003, 76, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jia, H. The Effects of Carbon–Silica Dual-Phase Filler on the Crosslink Structure of Natural Rubber. Polymers 2022, 14, 3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, M.; Gao, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Li, B.; Liu, K.; Liu, J. Hybrid Carbon Black/Silica Reinforcing System for High-Performance Green Tread Rubber. Polymers 2024, 16, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božeková, S.; Ondrušová, D.; Pajtášová, M.; Ďurišová, S.; Mičicová, Z.; Labaj, I.; Moricová, K.; Klepka, T.W. Effect of Alternative Carbon-Based Filler on Rubber Compounds Properties. Polimery 2023, 68, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, I.; Fleck, F.; Finger, S.; Sztucki, M.; Karimi-Varzaneh, H.A.; Lacayo-Pineda, J.; Giese, U. Effects of Silica Content on the Durability of Rubber Compounds Described by (Ultra) Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering. Polymer 2025, 321, 128097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suci, I.R.R.; Rahmah, A.U.; Budiyati, E.; Purnama, H. The Effect of Silica Filler Source on the Mechanical Properties of Composite Rubber. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 517, 12006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phumnok, E.; Khongprom, P.; Ratanawilai, S. Preparation of Natural Rubber Composites with High Silica Contents Using a Wet Mixing Process. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 8364–8376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choophun, N.; Chaiammart, N.; Sukthavon, K.; Veranitisagul, C.; Laobuthee, A.; Watthanaphanit, A.; Panomsuwan, G. Natural Rubber Composites Reinforced with Green Silica from Rice Husk: Effect of Filler Loading on Mechanical Properties. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hait, S.; Kumar, L.; Ijaradar, J.; Ghosh, A.K.; De, D.; Chanda, J.; Ghosh, P.; Das Gupta, S.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Wießner, S.; et al. Unlocking the Potential of Lignin: Towards a Sustainable Solution for Tire Rubber Compound Reinforcement. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, J.; Parathodika, A.R.; Hu, G.-H.; Naskar, K. Functional Rubber Composites Based on Silica-Silane Reinforcement for Green Tire Application: The State of the Art. Funct. Compos. Mater. 2022, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah Khalaf, E.S. A Comparative Study for the Main Properties of Silica and Carbon Black Filled Bagasse-Styrene Butadiene Rubber Composites. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2023, 31, 09673911231171035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabulov, A.T.; Beknazarov, K.I.; Tokpayev, R.R.; Atchabarova, A.A.; Bulybaev, M.E.; Khassanov, D.A.; Kubasheva, D.B.; Slyambayeva, A.K.; Kishibayev, K.K.; Nauryzbayev, M.K. Production of Dry Building Mixes Using Waste of the Mining and Metallurgical Complex of Kazakhstan. Int. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 15, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokpayev, R.R.; Atchabarova, A.A.; Abdullayeva, S.A.; Nechipurenko, S.V.; Yefremov, S.A.; Nauryzbayev, M.K. New Supports for Carbon-Metal Catalytic Systems Based on Shungite and Carbonizates of Plant Raw Materials. Eurasian Chem. J. 2015, 17, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchabarova, A.A.; Tokpayev, R.R.; Kabulov, A.T.; Nechipurenko, S.V.; Nurmanova, R.A.; Yefremov, S.A.; Nauryzbayev, M.K. New Electrodes Prepared from Mineral and Plant Raw Materials of Kazakhstan. Eurasian Chem. J. 2016, 18, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishibayev, K.K.; Serafin, J.; Tokpayev, R.R.; Khavaza, T.N.; Atchabarova, A.A.; Abduakhytova, D.A.; Ibraimov, Z.T.; Sreńscek-Nazzal, J. Physical and Chemical Properties of Activated Carbon Synthesized from Plant Wastes and Shungite for CO2 Capture. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, S.; Yang, L.; Liu, B.; Xie, S.; Qi, R.; Zhan, Y.; Xia, H. Graphene-Based Hybrid Fillers for Rubber Composites. Molecules 2024, 29, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Fei, G.; Salzano de Luna, M.; Lavorgna, M.; Xia, H. High Silica Content Graphene/Natural Rubber Composites Prepared by a Wet Compounding and Latex Mixing Process. Polymers 2020, 12, 2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Cao, J.-P.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Z.; Gao, Z. Silicon Dioxide Nanoparticle Decorated Graphene with Excellent Dispersibility in Natural Rubber Composites via Physical Mixing for Application in Green Tires. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 258, 110700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, E.N.; Salomatina, E.V.; Vassilyev, V.R.; Bannov, A.G.; Sandalov, S.I. Effect of Polynorbornene on Physico-Mechanical, Dynamic, and Dielectric Properties of Vulcanizates Based on Isoprene, α-Methylstyrene-Butadiene, and Nitrile-Butadiene Rubbers for Rail Fasteners Pads. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushmarin, N.F.; Efimovskii, E.G.; Petrova, N.N.; Sandalov, S.I.; Kol’tsov, N.I. The Influence of Powder Shungytes on Properties Of Oil-And Benzo Resistant Rubbers. Izv. Vyss. Uchebnykh Zaved. Khimiya I Khimicheskaya Tekhnologiya 2018, 62, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yefremov, S.A.; Kabulov, A.T.; Atchabarova, A.A.; Tokpayev, R.R.; Nechipurenko, S.V.; Nauryzbayev, M.K. Production of Shungite Concentrates–Multifunctional Fillers for Elastomers. In Proceedings of the XVIII International Coal Preparation Congress, Saint-Petersburg, Russia, 28 June–1 July 2016; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1193–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Polunina, I.A.; Vysotskii, V.V.; Senchikhin, I.N.; Polunin, K.E.; Goncharova, I.S.; Petukhova, G.A.; Buryak, A.K. The Effect of Modification on the Physicochemical Characteristics of Shungite. Colloid. J. 2017, 79, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komova, N.N.; Potapov, E.E.; Prut, E.V.; Solodilov, V.I.; Kovaleva, A.N. A Quick Method for Assessing the Activity of Shungite Filler in Elastomer Composite Materials. Int. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2018, 45, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechipurenko, S.V.; Bobrova, V.V.; Kasperovich, A.V.; Yermaganbetov, M.Y.; Yefremov, S.A.; Kaiaidarova, A.K.; Makhayeva, D.N.; Yermukhambetova, B.B.; Mun, G.A.; Irmukhametova, G.S. The Potential of Using Shungite Mineral from Eastern Kazakhstan in Formulations for Rubber Technical Products. Materials 2024, 18, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrova, V.V.; Nechipurenko, S.V.; Yermukhambetova, B.B.; Kasperovich, A.V.; Yefremov, S.A.; Kaiaidarova, A.K.; Makhayeva, D.N.; Irmukhametova, G.S.; Yeligbayeva, G.Z.; Mun, G.A. Application of Carbon–Silicon Hybrid Fillers Derived from Carbonised Rice Production Waste in Industrial Tread Rubber Compounds. Polymers 2025, 17, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beknazarov, K.; Tokpayev, R.; Nakyp, A.; Karaseva, Y.; Cherezova, E.; El Fray, M.; Volfson, S.; Nauryzbayev, M. Influence of Kazakhstan’s Shungites on the Physical–Mechanical Properties of Nitrile Butadiene Rubber Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechipurenko, S.V.; Efremov, S.A.; Zabara, N.A.; Kasperovich, A.V.; Abzaldinov, K.S.; Stoyanov, O.V.; Yarullin, A.F. Composite materials based on methylstyrene butadiene rubber and carbon-mineral fillers. Her. Technol. Univ. 2023, 26, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, E.S.; Potapov, E.E.; Bobrov, A.P.; Smal, V.A.; Erokhin, A.I.; Plotnikova, M.F. A Study of the Possibility of Using Shungite in Latex Rubber Formulations for the Manufacture of Gloves with High Resistance to Aggressive Media. Int. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2016, 43, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garishin, O.K.; Shadrin, V.V.; Belyaev, A.Y.; Kornev Yu, V. Kornev Micro and Nanoshungites—Perspective Mineral Fillers for Rubber Composites Used in the Tires. Mater. Phys. Mech. 2018, 40, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauylbek, A.; Rakhmatullina, A.; Nakyp, A.; Turmanov, R.; Zhanbekov, K. Zhanbekov Modification of Synthetic Isoprene Rubber with Phospholipid Concentrate during the Stage of Rubber Extraction from Polymerizate. Chem. Methodol. 2026, 10, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, G.; Klüppel, M.; Vilgis, T.A. Reinforcement of Elastomers. Curr. Opin. Solid. State Mater. Sci. 2002, 6, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, B.B. Role of Particulate Fillers in Elastomer Reinforcement: A Review. Polymer 1979, 20, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnevskii, K.V.; Kurmashov, P.B.; Golovakhin, V.; Maksimovskiy, E.A.; Jin, H.; Shashok, Z.S.; Bannov, A.G. The Role of Graphite-like Materials in Modifying the Technological Properties of Rubber Composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ji, L.; Sun, Z.; Sun, J.; Han, Z.; Ma, Q.; Yang, H.; Ke, Y.; et al. Natural Coal-Derived Graphite as Rubber Filler and the Influence of Its Progressive Graphitization on Reinforcement Performance. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 184, 108237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozhkova, N.N. Role of Fullerene-like Structures in the Reactivity of Shungite Carbon as Used in New Materials with Advanced Properties. In Perspectives of Fullerene Nanotechnology; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 237–251. [Google Scholar]

- Okhotina, N.A.; Kurbangaleeva, A.R.; Panfilova, O.A. Syr’e i Materialy Dlya Rezinovoj Promyshlennosti (Raw and Other Materials for the Rubber Industry); Kazan National Research Technological University: Kazan, Russia, 2014; Izd-vo Kazan. nats. isl. technol. un-ta. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.-J. Effect of Polymer-Filler and Filler-Filler Interactions on Dynamic Properties of Filled Vulcanizates. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1998, 71, 520–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, J.C.; Schneider, M.; Hauler, O.; Lorenz, G.; Rebner, K.; Kandelbauer, A. A Process Analytical Concept for In-Line FTIR Monitoring of Polysiloxane Formation. Polymers 2020, 12, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Kaya, H.; Lin, Y.; Ogrinc, A.; Kim, S.H. Vibrational Spectroscopy Analysis of Silica and Silicate Glass Networks. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 2355–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, C.S.; Kim, K.-J. Interfacial Adhesion in Silica-Silane Filled NR Composites: A Short Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, J.; Niedermeier, W.; Luginsland, H.-D. The Effect of Filler–Filler and Filler–Elastomer Interaction on Rubber Reinforcement. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2005, 36, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smejda-Krzewicka, A.; Mrozowski, K. Chloroprene and Butadiene Rubber (CR/BR) Blends Cross-Linked with Metal Oxides: INFLUENCE of Vulcanization Temperature on Their Rheological, Mechanical, and Thermal Properties. Molecules 2025, 30, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfannakh, H.; Alnaim, N.; Ibrahim, S.S. Thermal Stability and Non-Isothermal Kinetic Analysis of Ethylene–Propylene–Diene Rubber Composite. Polymers 2023, 15, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Savino, I.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy to Assess the Degree of Alteration of Artificially Aged and Environmentally Weathered Microplastics. Polymers 2023, 15, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandt, C.; Waeytens, J.; Deniset-Besseau, A.; Nielsen-Leroux, C.; Réjasse, A. Use and Misuse of FTIR Spectroscopy for Studying the Bio-Oxidation of Plastics. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 258, 119841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, D.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Kaya, H.; Zimudzi, T.J.; Gin, S.; Mahadevan, T.; Du, J.; Kim, S.H. Hydrogen Bonding Interactions of H2O and SiOH on a Boroaluminosilicate Glass Corroded in Aqueous Solution. npj Mater. Degrad. 2020, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Shi, L.; Huang, H.; Ye, K.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, D.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, L.; et al. Analysis of Aged Microplastics: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1861–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosu, E.; Hirano, Y.; Kumagai, S.; Saito, Y.; Tahara, S.; Nasi, T.; Homma, M.; Minato, T.; Hojo, M.; Yoshioka, T. Pyrolysis Characteristics of Tire Rubber at Low Temperatures. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 8119–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thitithammawong, A.; Saiwari, S.; Salaeh, S.; Hayeemasae, N. Potent Application of Scrap from the Modified Natural Rubber Production as Oil Absorbent. Polymers 2022, 14, 5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olewnik-Kruszkowska, E.; Adamczyk, A.; Gierszewska, M.; Grabska-Zielińska, S. Comparison of How Graphite and Shungite Affect Thermal, Mechanical, and Dielectric Properties of Dielectric Elastomer-Based Composites. Energies 2021, 15, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żenkiewicz, M.; Richert, J.; Rytlewski, P.; Richert, A. Comparative Analysis of Shungite and Graphite Effects on Some Properties of Polylactide Composites. Polym. Test. 2011, 30, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Ingredients | Sample Designation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sh0 | Sh10 | Sh15 | Sh20 | ||

| Content, phr * | |||||

| 1 | SBR-1705 HI-AR | 80.0 | 80.0 | 80.0 | 80.0 |

| 2 | IR SKI-3 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| 3 | Sulfur | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 4 | DPG | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 5 | MBTS | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 6 | ZnO | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| 7 | Stearic acid | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 8 | Carbon black P 354 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| 9 | BS-100 | 45.0 | 35.0 | 30.0 | 25.0 |

| 10 | Shungite | 0 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 20.0 |

| Element | C | O | Na | Mg | Al | Si | K | Ca | Ti | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.%. | 13.5 | 45.9 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 9.5 | 19.0 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 4.5 |

| Component | C | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | K2O | TiO2 | CaO | Na2O | MgO | P2O5 | MnO | SO3 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content, wt.% | 13 | 49.44 | 21.13 | 6.75 | 3.42 | 3.06 | 2.47 | 1.77 | 1.31 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.23 |

| Parameter | Sample Designation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sh0 | Sh10 | Sh15 | Sh20 | |

| ts, min | 0.41 | 3.65 | 4.02 | 4.44 |

| ML, dN·m | 3.49 | 2.99 | 2.21 | 1.77 |

| MH, dN·m | 22.21 | 17.28 | 15.45 | 13.92 |

| t90, min | 17.90 | 18.32 | 16.15 | 16.95 |

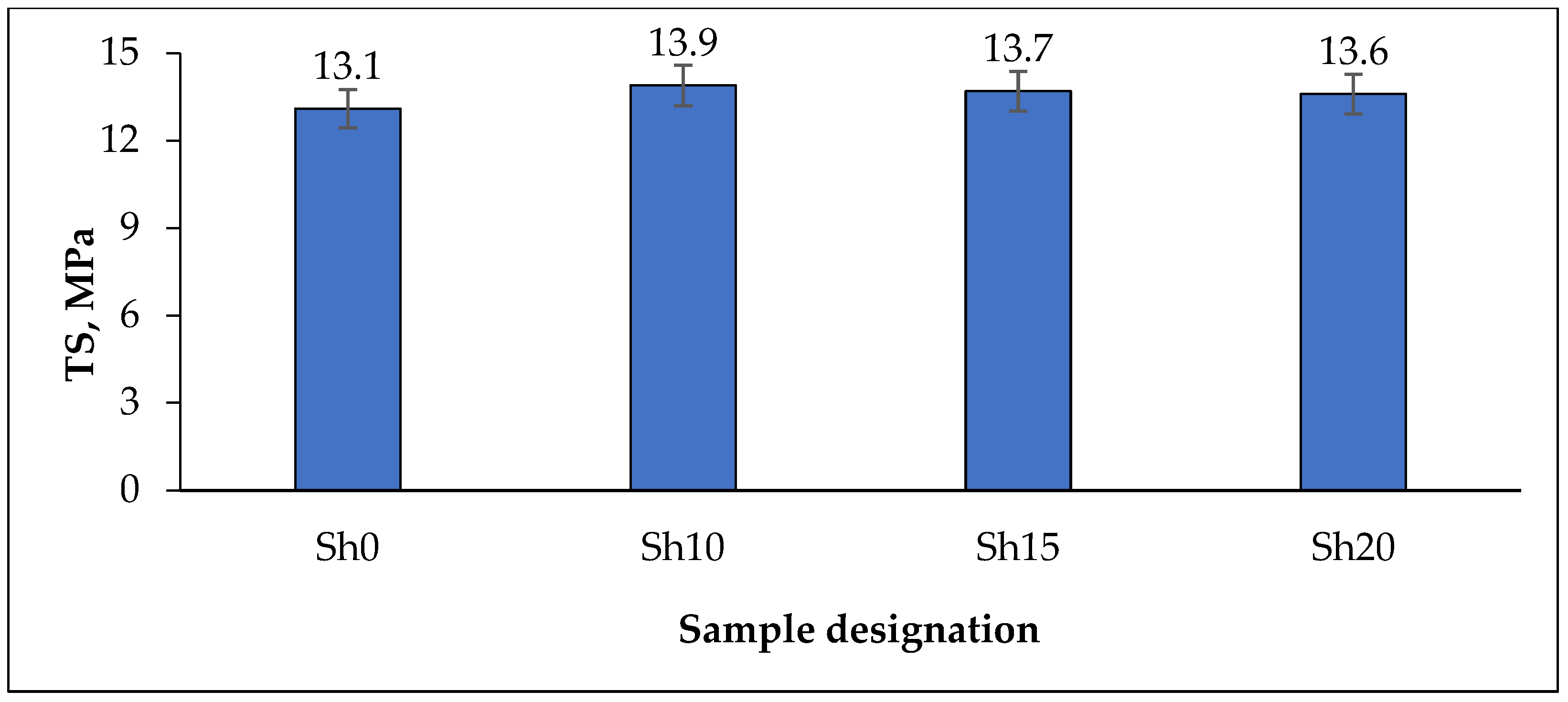

| Sample Designation (Table 1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sh0 | Sh10 | Sh15 | Sh20 | |

| Tensile strength (TS) | ||||

| TS, MPa | 11.2 | 11.8 | 10.3 | 9.7 |

| * ∆fp, % | −14.5 | −15.1 | −24.8 | −28.7 |

| Elongation at break (ε) | ||||

| ε, % | 544 | 576 | 540 | 528 |

| * ∆ε, % | −32.8 | −22.2 | −28.0 | −29.6 |

| Rebound resilience (R) | ||||

| R, % | 33 | 36 | 38 | 40 |

| * ∆R, % | 26.9 | 20 | 11.8 | 8.1 |

| Hardness, Shore A (HSA) | ||||

| HSA | 64 | 63 | 63 | 62 |

| * ∆HSA, % | −4.5 | −3.1 | −1.6 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beknazarov, K.; Nakyp, A.; Cherezova, E.; Karaseva, Y.; Khasanov, A.; Ignaczak, W.; Tokpayev, R.; Nauryzbayev, M. Influence of Shungite from the Bakyrchik Deposit on the Properties of Rubber Composites Based on a Blend of Non-Polar Diene Rubbers. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120707

Beknazarov K, Nakyp A, Cherezova E, Karaseva Y, Khasanov A, Ignaczak W, Tokpayev R, Nauryzbayev M. Influence of Shungite from the Bakyrchik Deposit on the Properties of Rubber Composites Based on a Blend of Non-Polar Diene Rubbers. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):707. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120707

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeknazarov, Kanat, Abdirakym Nakyp, Elena Cherezova, Yulia Karaseva, Azat Khasanov, Wojciech Ignaczak, Rustam Tokpayev, and Mikhail Nauryzbayev. 2025. "Influence of Shungite from the Bakyrchik Deposit on the Properties of Rubber Composites Based on a Blend of Non-Polar Diene Rubbers" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120707

APA StyleBeknazarov, K., Nakyp, A., Cherezova, E., Karaseva, Y., Khasanov, A., Ignaczak, W., Tokpayev, R., & Nauryzbayev, M. (2025). Influence of Shungite from the Bakyrchik Deposit on the Properties of Rubber Composites Based on a Blend of Non-Polar Diene Rubbers. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120707