Effect of Detonation Nanodiamonds on Physicochemical Properties and Hydrolytic Stability of Magnesium Potassium Phosphate Composite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of MPP-ND Composite Samples

2.2. Research Methods of Experimental Samples

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Elemental Composition and Functional Groups of NDs Surface

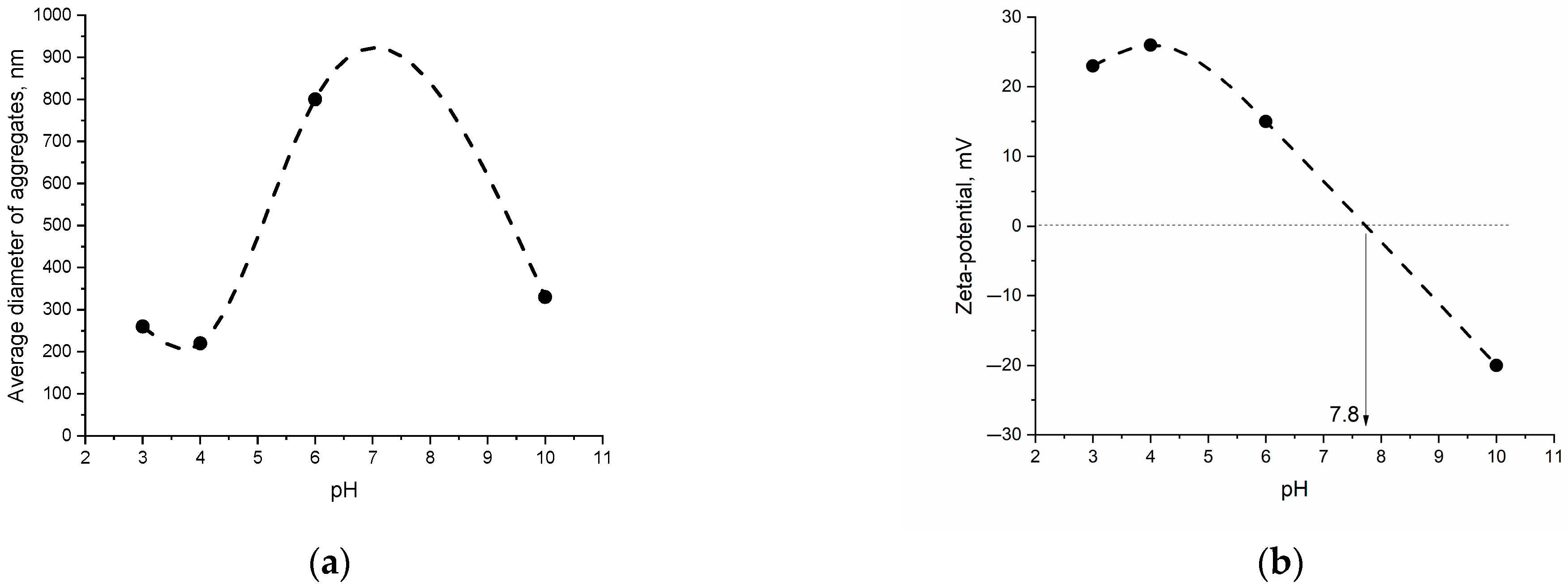

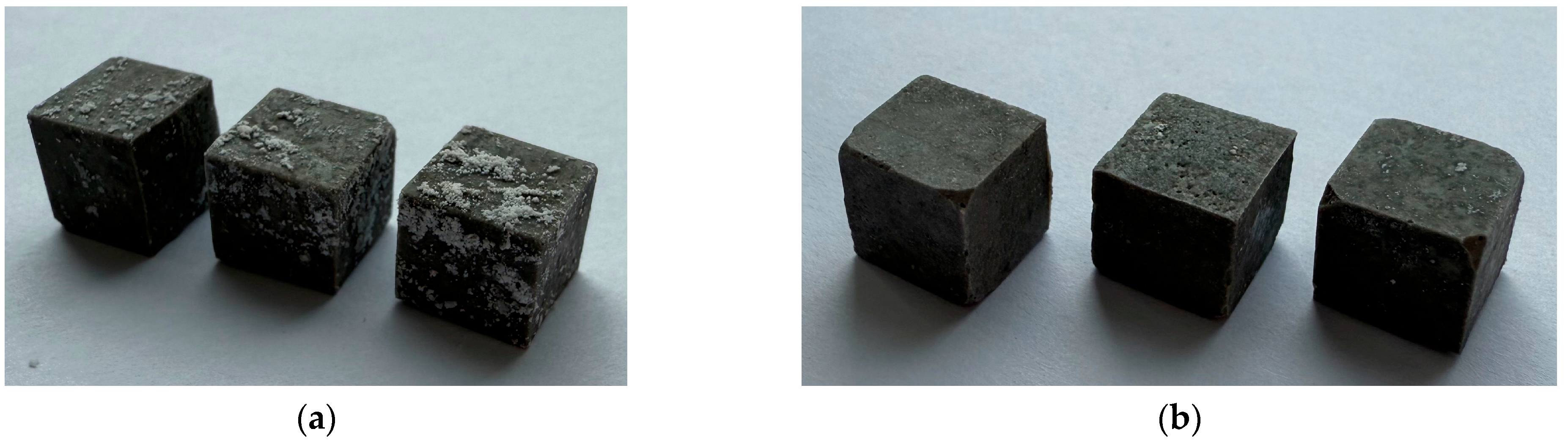

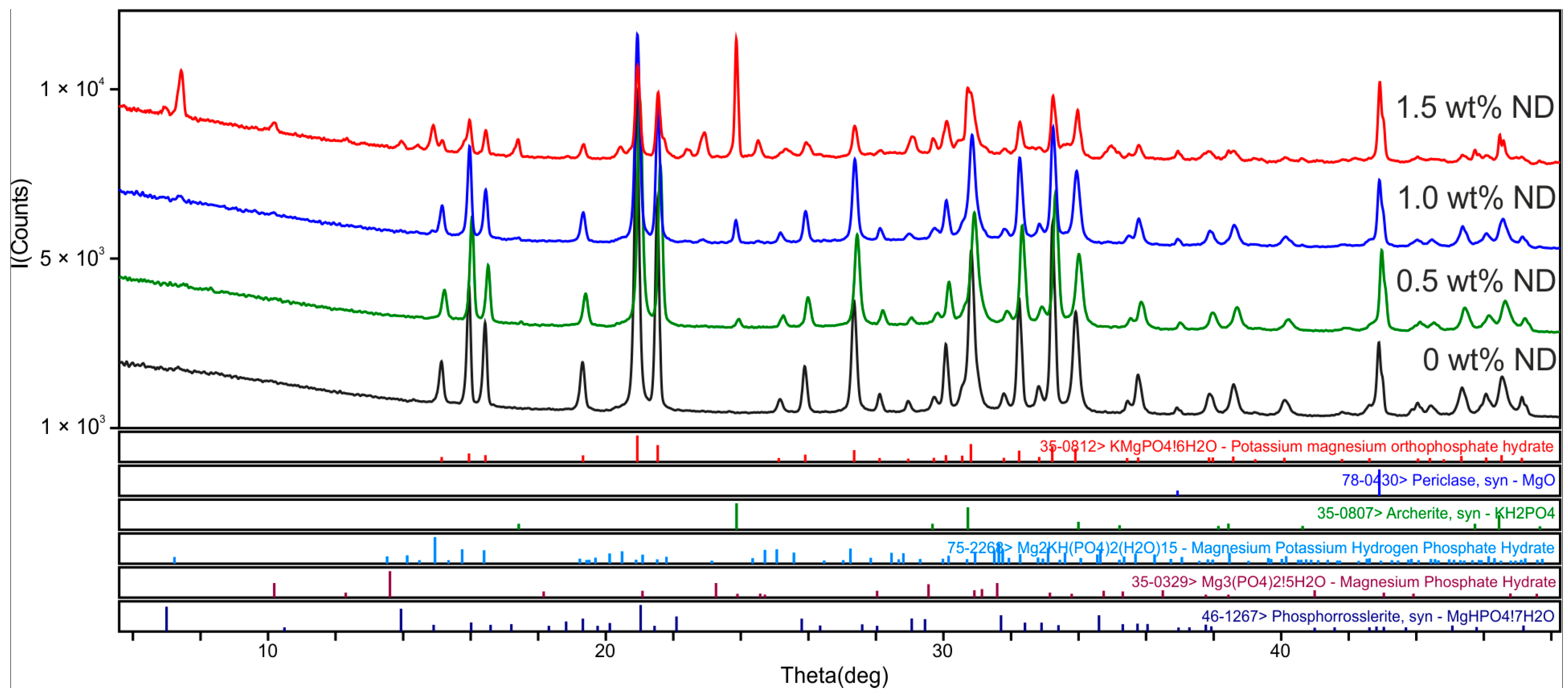

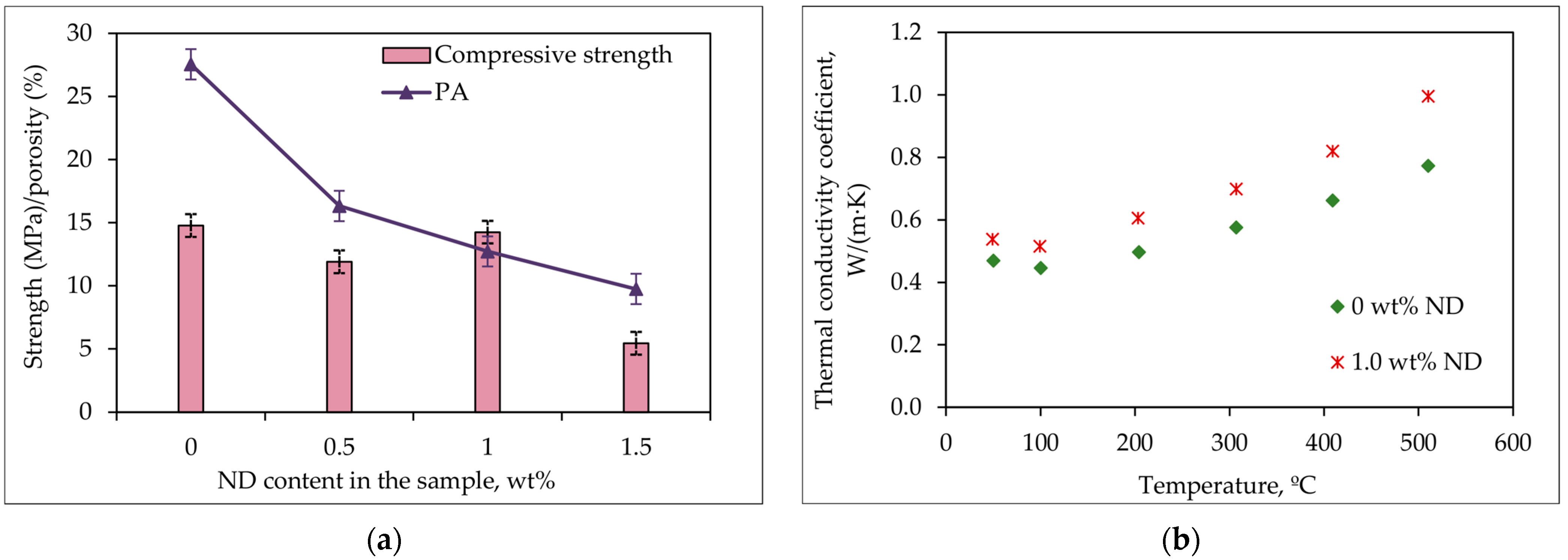

3.2. Choice of Optimal Filling of MPP-ND Composite by NDs

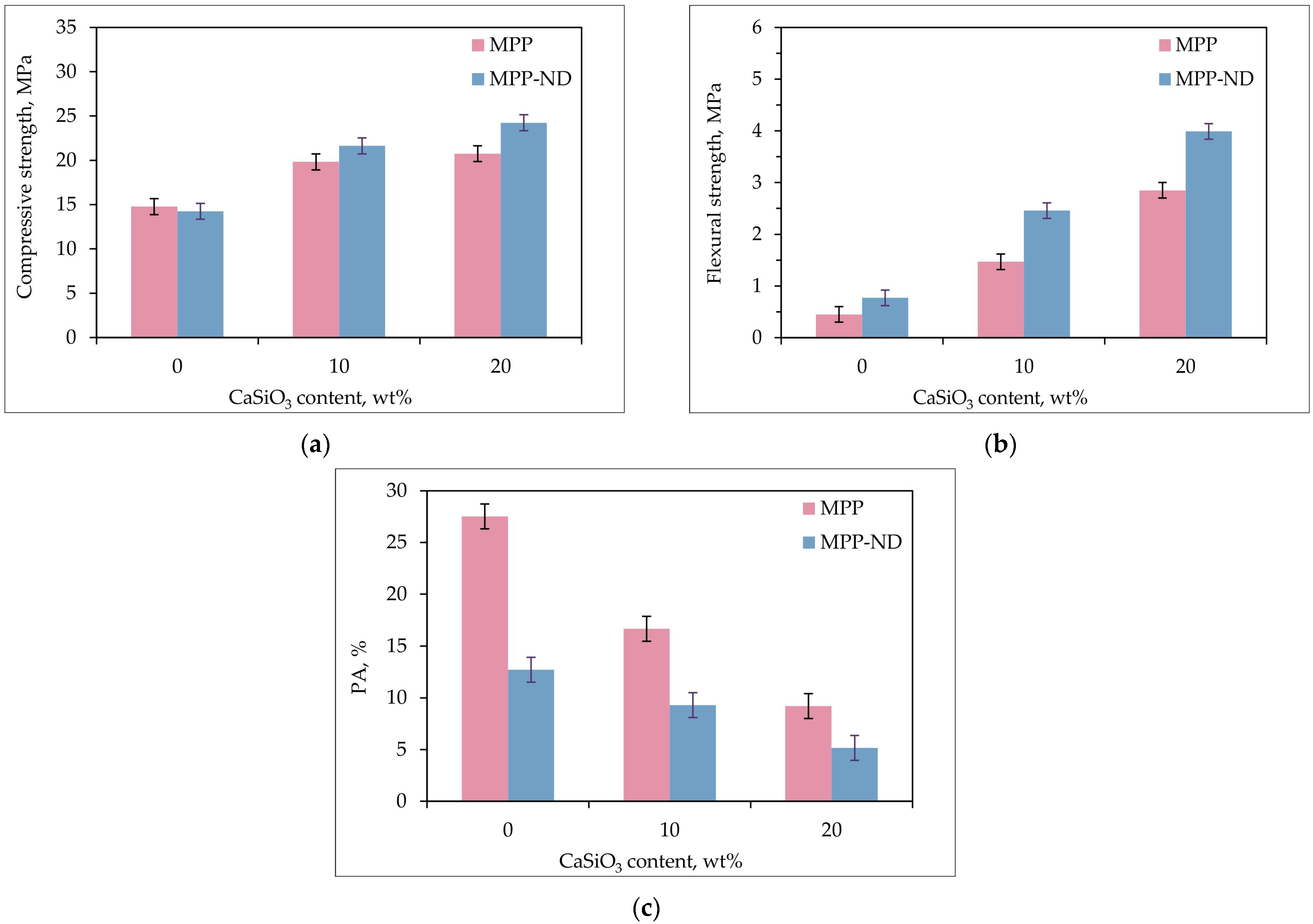

3.3. Choice of Optimal Filling of MPP-ND Composite by Wollastonite

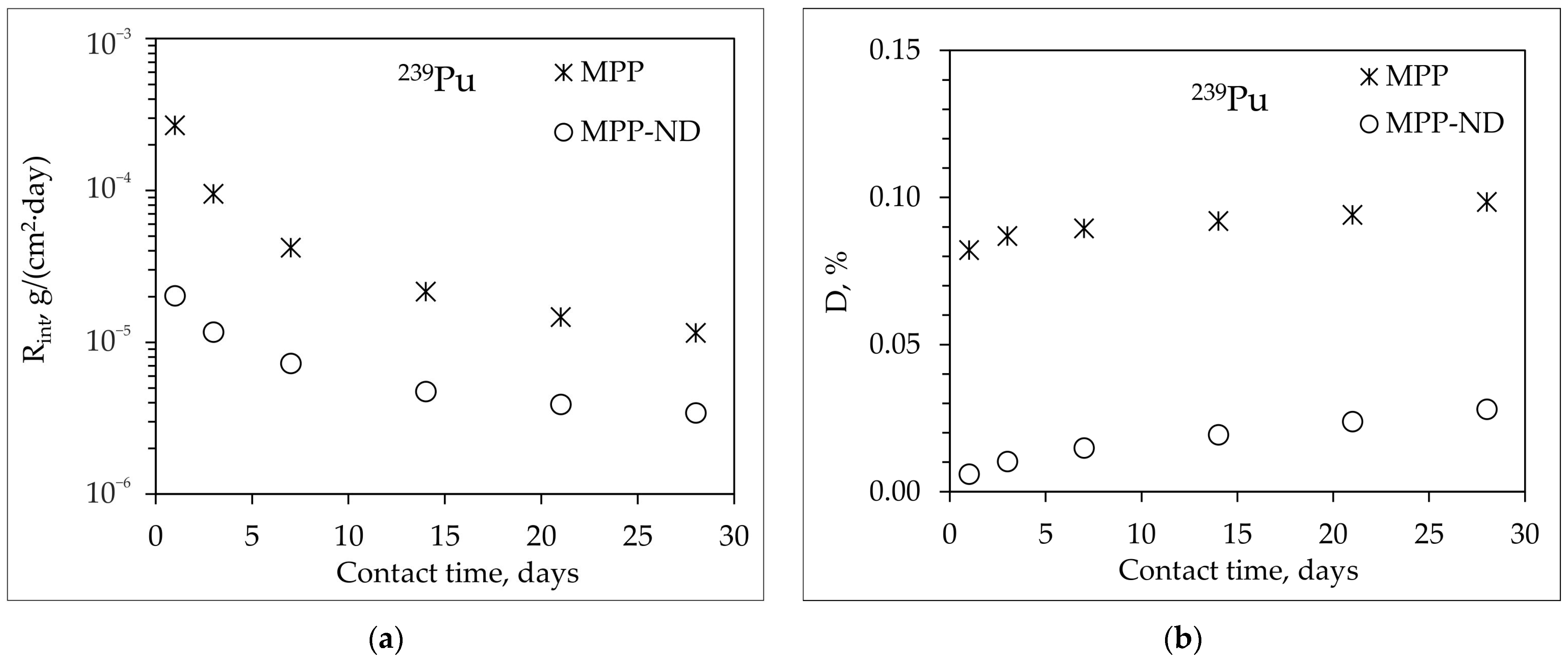

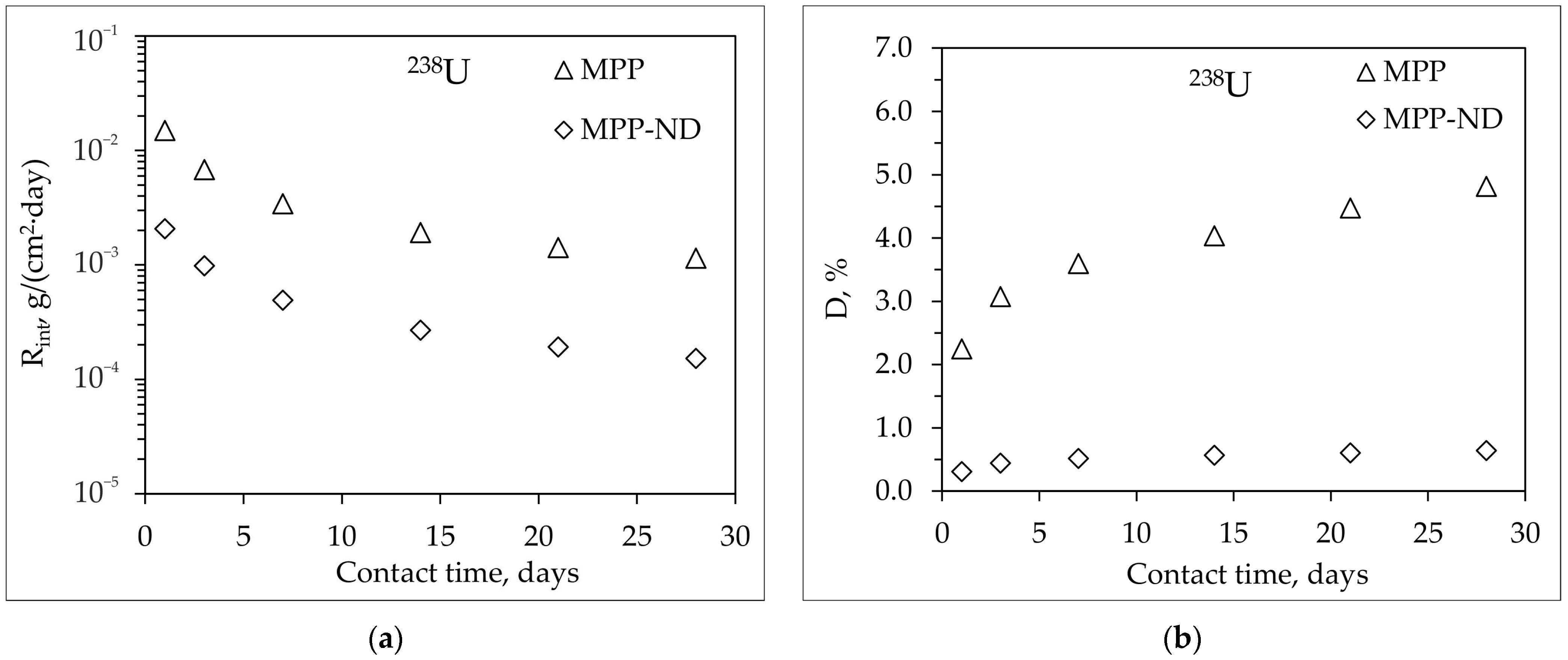

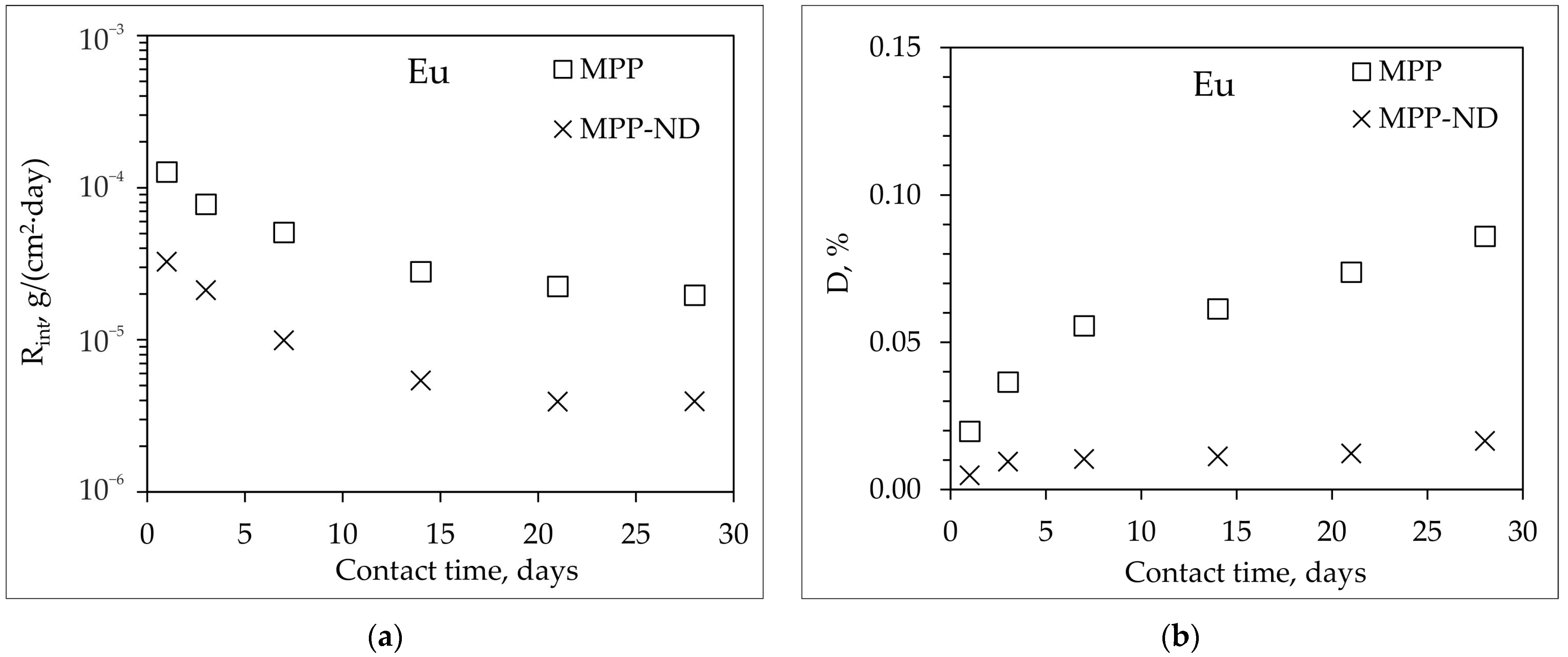

3.4. Hydrolytic Stability of MPP-ND Composite

4. Conclusions

- The strength of the MPP-ND composite containing ≤1.0 wt% NDs is about 12–14 MPa;

- All samples containing ≤1 wt% NDs are resistant to freeze/thaw thermal cycles;

- The porosity of the samples decreases from 27.5% to 9.7% when introducing up to 1.5 wt% NDs into the blank sample;

- The thermal conductivity coefficient of the MPP-ND composite increases by 22% with the introduction of 1 wt% NDs and amounts to values at the level of (0.5–1.0) W/(m∙K) in the range (47–510) °C;

- Based on the results of the phase composition, compressive strength, porosity, and thermal conductivity of the MPP-ND composite samples, it was noted that optimal filling of the MPP matrix is 1 wt% NDs;

- The MPP-ND composite containing 1 wt% NDs and 20 wt% wollastonite has a maximum compressive strength of 24 MPa and a maximum flexural strength of 4 MPa with a minimum porosity of no more than 5%;

- The addition of 1 wt% NDs to the MPP-ND composite leads to a decrease in the rate and degree of leaching of 239Pu, 238U, and Eu of 3.5, 7.5 and 5 times, respectively.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GO | graphene oxide |

| CNTs | carbon nanotubes |

| MPP matrix | magnesium potassium phosphate matrix |

| MPP-ND composite | composite based on a magnesium potassium phosphate matrix containing nanodiamonds |

| NDs | nanodiamonds |

| RW | radioactive waste |

| PA | apparent porosity |

| FTIR | fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Malkovsky, V.; Liebscher, A.; Nagel, T.; Magri, F. Influence of tectonic perturbations on the migration of long-lived radionuclides from an underground repository of radioactive waste. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drace, Z.; Ojovan, M.I.; Samanta, S.K. Challenges in Planning of Integrated Nuclear Waste Management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantzen, C.M.; Lee, W.E.; Ojovan, M.I. Radioactive waste (RAW) conditioning, immobilization, and encapsulation processes and technologies: Overview and advances. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy, Radioactive Waste Management and Contaminated Site Clean-Up; Lee, W.E., Ojovan, M.I., Jantzen, C.M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 171–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikova, S.A.; Danilov, S.S.; Matveenko, A.V.; Frolova, A.V.; Belova, K.Y.; Petrov, V.G.; Vinokurov, S.E.; Myasoedov, B.F. Perspective Compounds for Immobilization of Spent Electrolyte from Pyrochemical Processing of Spent Nuclear Fuel. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhimova, N. Recent Advances in Alternative Cementitious Materials for Nuclear Waste Immobilization: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, A.S. Chemically Bonded Phosphate Ceramics: Twenty-First Century Materials with Diverse Applications, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1–422. ISBN 978-0-08-100380-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vinokurov, S.E.; Kulikova, S.A.; Myasoedov, B.F. Magnesium Potassium Phosphate Compound for Immobilization of Radioactive Waste Containing Actinide and Rare Earth Elements. Materials 2018, 11, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Yan, T.; Lu, Z.; Lv, S.; Zhang, H. Rapid solidification of highly loaded high-level liquid wastes with magnesium phosphate cement. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 5050–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayenko, S.Y.; Shkuropatenko, V.A.; Pylypenko, O.V.; Karsim, S.O.; Zykova, A.V.; Kutni, D.V.; Wagh, A.S. Radioactive waste immobilization of Hanford sludge in magnesium potassium phosphate ceramic forms. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2022, 152, 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokurov, S.E.; Kulikova, S.A.; Frolova, A.V.; Danilov, S.S.; Belova, K.Y.; Rodionova, A.A.; Myasoedov, B.F. New Methods and Materials in Nuclear Fuel Fabrication and Spent Nuclear Fuel and Radioactive Waste Management. In Advances in Geochemistry, Analytical Chemistry, and Planetary Sciences; Kolotov, V.P., Bezaeva, N.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattori, F.; Magugliani, G.; Santi, A.; Mossini, E.; Moschetti, I.; Galluccio, F.; Macerata, E.; de la Bernardie, X.; Abdelouas, A.; Cori, D.; et al. Radiation stability and durability of magnesium phosphate cement for radioactive reactive metals encapsulation. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 177, 105463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazorenko, G.; Kasprzhitskii, A. A review of magnesium-rich wastes and by-products as precursors for magnesium phosphate cements: Challenges and opportunities. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokurov, S.E.; Kulikova, S.A.; Myasoedov, B.F. Hydrolytic and thermal stability of magnesium potassium phosphate compound for immobilization of high level waste. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2018, 318, 2401–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikova, S.A.; Danilov, S.S.; Belova, K.Y.; Rodionova, A.A.; Vinokurov, S.E. Optimization of the solidification method of high-level waste for increasing the thermal stability of the magnesium potassium phosphate compound. Energies 2020, 13, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plecas, I.; Dimovic, S.; Smiciklas, I. Utilization of bentonite and zeolite in cementation of dry radioactive evaporator concentrate. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2006, 48, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhar, I.; Luhar, S.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Sandu, A.V.; Vizureanu, P.; Razak, R.A.; Burduhos-Nergis, D.D.; Imjai, T. Solidification/Stabilization Technology for Radioactive Wastes Using Cement: An Appraisal. Materials 2023, 16, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Das, B.B.; Qureshi, T.; Adak, D. Cement-based solidification of nuclear waste: Mechanisms, formulations and regulatory considerations. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 120712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, J.A.; Hawileh, R.A.; Bahurudeen, A.; Jittin, V.; Kabeer, K.S.A.; Thomas, B.S. Influence of synthesized nanomaterials in the strength and durability of cementitious composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakov, A.G.; Pavlova, D.V.; Vinokurov, S.E.; Myasoedov, B.F. Sorption of americium from aqueous solutions of various compositions onto detonation synthesis nanodiamonds. Radiochemistry 2025, 67, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, L.S.; Hortiguela, M.J.; Singh, M.K.; Sousa, A.C.M. Thermal conductivity and viscosity of water based nanodiamond (ND) nanofluids: An experimental study. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 76, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, R. Effect of graphene nano-sheets on the chloride penetration and microstructure of the cement based composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 161, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiříčková, A.; Lauermannová, A.-M.; Jankovský, O.; Lojka, M.; Záleská, M.; Pivák, A.; Pavlíková, M.; Merglová, A.; Pavlík, Z. Impact of nano-dopants on the mechanical and physical properties of magnesium oxychloride cement composites—Experimental assessment. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 108981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.M.; Li, W.G.; Li, C.Y.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Duan, W.H.; Li, Z. Effects of graphene oxide agglomerates on workability, hydration, microstructure and compressive strength of cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 145, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Qian, S.; Liu, X.; Gao, R.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, Z. Carbon dots as a superior building nanomaterial for enhancing the mechanical properties of cement-based composites. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Reza, H. Mohammadian Role carbon nanomaterials in reinforcement of concrete and cement; A new perspective in civil engineering. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 72, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y. Study on graphene oxide reinforced magnesium phosphate cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 359, 129523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Hou, D.; Ma, H.; Fan, T.; Li, Z. Effects of graphene oxide on the properties and microstructures of the magnesium potassium phosphate cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 119, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, H. Experimental study on the effect of different dispersed degrees carbon nanotubes on the modification of magnesium phosphate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 200, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yang, J.; Thomas, B.S.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Shaban, W.M.; Chong, W.T. Influence of hybrid graphene oxide/carbon nanotubes on the mechanical properties and microstructure of magnesium potassium phosphate cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 120449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokurov, S.E.; Kulikova, S.A.; Krupskaya, V.V.; Myasoedov, B.F. Magnesium potassium phosphate compound for radioactive waste immobilization: Phase composition, structure, and physicochemical and hydrolytic durability. Radiochemistry 2018, 60, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 4526-75; Reagents. Magnesium Oxide. Specifications. IPC Publishing House of Standards: Moscow, Russia, 1975; pp. 1–11.

- GOST 4198-75; Reagents. Potassium Dihydrogen Phosphate. Specifications. Standartinform: Moscow, Russia, 2010; pp. 1–16.

- GOST 9656-75; Reagents. Boric Acid. Specifications. Standartinform: Moscow, Russia, 2006; pp. 1–10.

- Kazakov, A.G.; Pavlova, D.V.; Ekatova, T.Y.; Larkina, M.S.; Varvashenya, R.N.; Yanovich, G.E.; Plotnikov, E.V.; Ushakov, I.A.; Nesterov, E.A.; Zukau, V.V.; et al. Preparation of a nanodiamond suspension with immobilized lutetium-177 and study of its biodistribution. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2025, 334, 6029–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakov, A.G.; Babenya, J.S.; Ekatova, T.Y.; Vinokurov, S.E.; Khvorostinin, E.Y.; Ushakov, I.A.; Zukau, V.V.; Stasyuk, E.S.; Nesterov, E.A.; Sadkin, V.L.; et al. The Influence of the Sizes of Nanodiamond Aggregates in Suspensions on the Efficiency of Sorption of 90Y and 177Lu Isotopes for Further Use in Nuclear Medicine. Radiochemistry 2024, 66, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulagin, V.A.; Kulagina, T.A.; Nikiforova, E.M.; Prikhodov, D.A.; Shimanskiy, A.F. Improvment of mechanical properties of the cement compound in order to increase the degree of its filling. J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Eng. Technol. 2018, 11, 711–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakov, A.G.; Garashchenko, B.L.; Yakovlev, R.Y.; Vinokurov, S.E.; Kalmykov, S.N.; Myasoedov, B.F. An experimental study of sorption/desorption of selected radionuclides on carbon nanomaterials: A quest for possible applications in future nuclear medicine. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2020, 104, 107752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevanagoudar, Y.V.; Krishna, R.H.; Gowda, R.; Preetham, R.; Prabhakara, R. Improved mechanical properties and piezoresistive sensitivity evaluation of MWCNTs reinforced cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 144, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 310.4-81; Cements. Methods of Tests of Bending and Compression Strengths. IPC Publishing House of Standards: Moscow, Russia, 2003; pp. 1–11.

- NP-019-15; Federal Norms and Rules in the Field of Atomic Energy Use “Collection, Processing, Storage and Conditioning of Liquid Radioactive Waste. Safety Requirements”. Rostekhnadzor: Moscow, Russia, 2015; pp. 1–22.

- Kulikova, S.A.; Belova, K.Y.; Frolova, A.V.; Vinokurov, S.E. The Use of Dolomite to Produce a Magnesium Potassium Phosphate Matrix for Radioactive Waste Conditioning. Energies 2023, 16, 5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza-Benzal, A.; Ferrández, D.; Barrios, A.M.; Morón, C. Water Resistance Analysis of New Lightweight Gypsum-Based Composites Incorporating Municipal Solid Waste. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST R 52126-2003; Radioactive Waste. Long Time Leach Testing of Solidified Radioactive Waste Forms. Gosstandart 305: Moscow, Russia, 2003; pp. 1–8.

- Diederich, L.; Küttel, O.M.; Ruffieux, P.; Pillo, T.; Aebi, P.; Schlapbach, L. Photoelectron emission from nitrogen- and boron-doped diamond (100) surfaces. Surf. Sci. 1998, 417, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smentkowski, V.S.; Jänsch, H.; Henderson, M.A.; Yates, J.T. Deuterium atom interaction with diamond (100) studied by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Surf. Sci. 1995, 330, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Database, Version 4.1—Gaithersburg: National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2012. Available online: http://srdata.nist.gov/xps (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Beamson, G.; Briggs, D. High Resolution XPS of Organic Polymers: The Scienta ESCA 300 Database; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1992; 295p. [Google Scholar]

- Graeser, S.; Postl, W.; Bojar, H.-P.; Berlepsch, P.; Armbruster, T.; Raber, T.; Ettinger, K.; Walter, F. Struvite-(K), KMgPO4∙6H2O, the potassium equivalent of struvite—A new mineral. Eur. J. Miner. 2008, 20, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothenbach, B.; Xu, B.; Winnefeld, F. Thermodynamic data for magnesium (potassium) phosphates. Appl. Geochem. 2019, 111, 104450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Cau Dit Coumes, C.; Lambertin, D.; Lothenbach, B. Compressive strength and hydrate assemblages of wollastonite-blended magnesium potassium phosphate cements exposed to different pH conditions. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 143, 105255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidalov, S.V.; Shakhov, F.M.; Vul, A.Y. Thermal conductivity of sintered nanodiamonds and microdiamonds. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2008, 17, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Spectrum | Type of Binding | Content, at% |

|---|---|---|

| C1s | C–C (sp2) | 11.3 |

| C–C (diamond) | 40.3 | |

| C–C (diamond H-terminated), C–O | 35.6 | |

| O=C–O | 3.2 | |

| C–C (sp2) | 0.7 | |

| O1s | O2− | 3.9 |

| O=C | 3.2 | |

| O–C | 11.3 | |

| N1s | NR3 | 0.7 |

| NR2C=O | 0.5 | |

| R–N=O | 0.3 | |

| –NO2 | 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fimina, S.A.; Chalysheva, N.D.; Belova, K.Y.; Kazakov, A.G.; Vinokurov, S.E.; Myasoedov, B.F. Effect of Detonation Nanodiamonds on Physicochemical Properties and Hydrolytic Stability of Magnesium Potassium Phosphate Composite. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120688

Fimina SA, Chalysheva ND, Belova KY, Kazakov AG, Vinokurov SE, Myasoedov BF. Effect of Detonation Nanodiamonds on Physicochemical Properties and Hydrolytic Stability of Magnesium Potassium Phosphate Composite. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):688. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120688

Chicago/Turabian StyleFimina, Svetlana A., Nataliya D. Chalysheva, Kseniya Y. Belova, Andrey G. Kazakov, Sergey E. Vinokurov, and Boris F. Myasoedov. 2025. "Effect of Detonation Nanodiamonds on Physicochemical Properties and Hydrolytic Stability of Magnesium Potassium Phosphate Composite" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120688

APA StyleFimina, S. A., Chalysheva, N. D., Belova, K. Y., Kazakov, A. G., Vinokurov, S. E., & Myasoedov, B. F. (2025). Effect of Detonation Nanodiamonds on Physicochemical Properties and Hydrolytic Stability of Magnesium Potassium Phosphate Composite. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120688