Synthesis of Halogen-Containing Methylenedianiline Derivatives as Curing Agents for Epoxy Resins and Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Their Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.3. Synthesis of Curing Agents

2.4. Resin Preparation

2.5. Vacuum Infusion Process

- Heating to a temperature of 180 °C at a rate of 2 °C per minute and maintaining that temperature for 3 h.

- Cooling to a temperature not exceeding 50 °C at a rate not greater than 5 °C/min.

- Cooling to room temperature.

2.6. Water Absorption

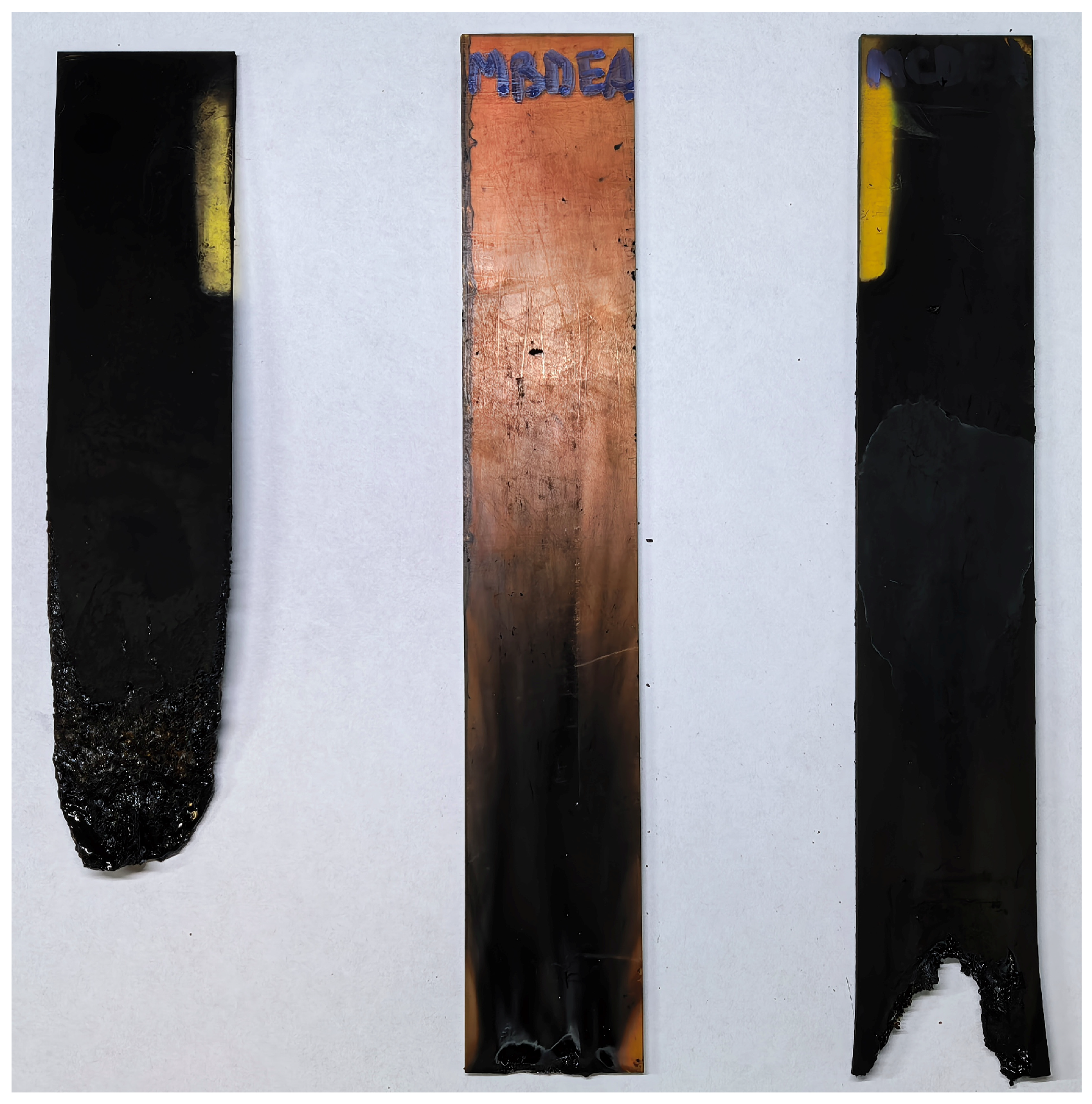

2.7. Fire Tests

3. Results and Discussions

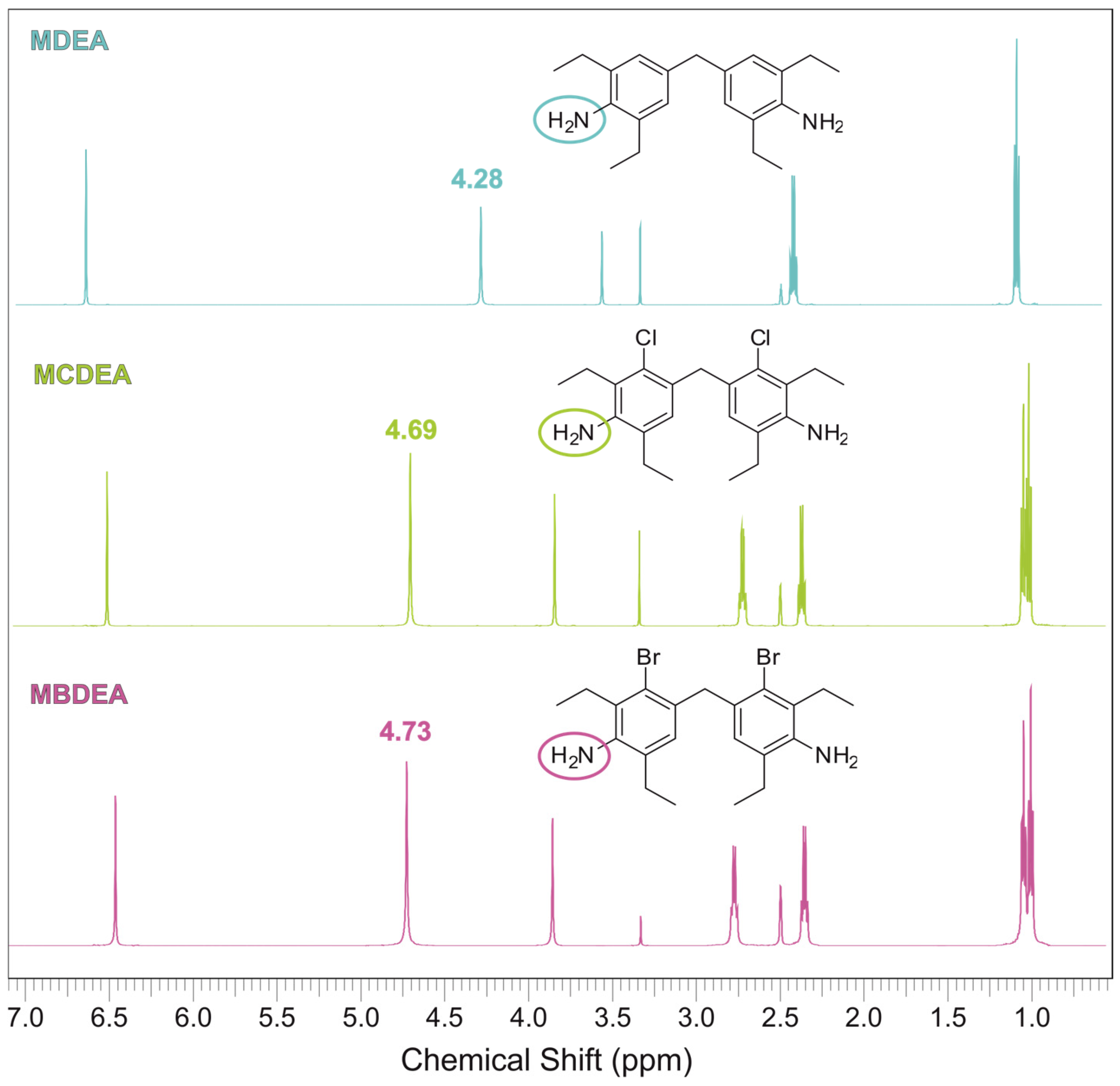

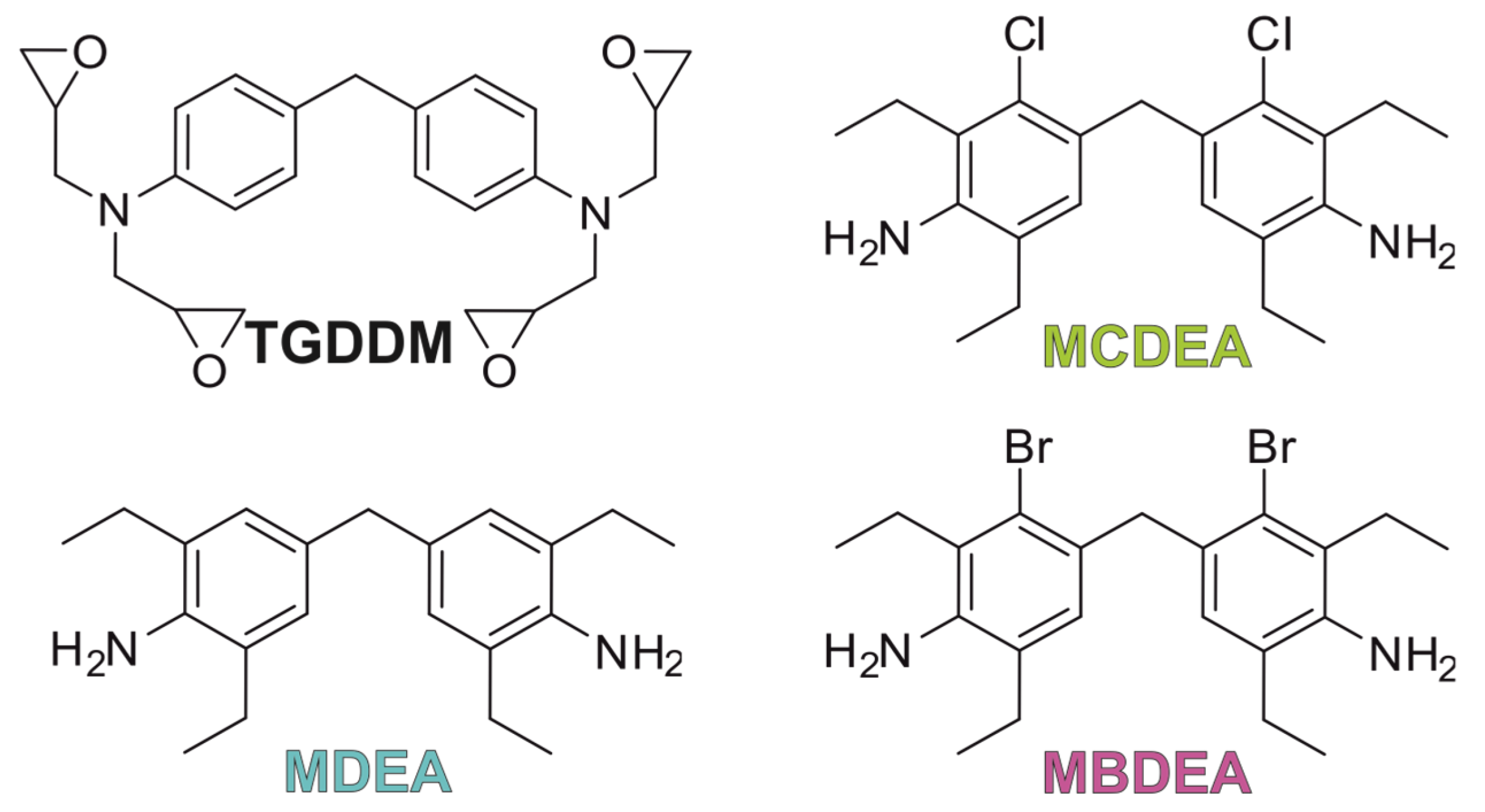

3.1. Synthesis of MBDEA

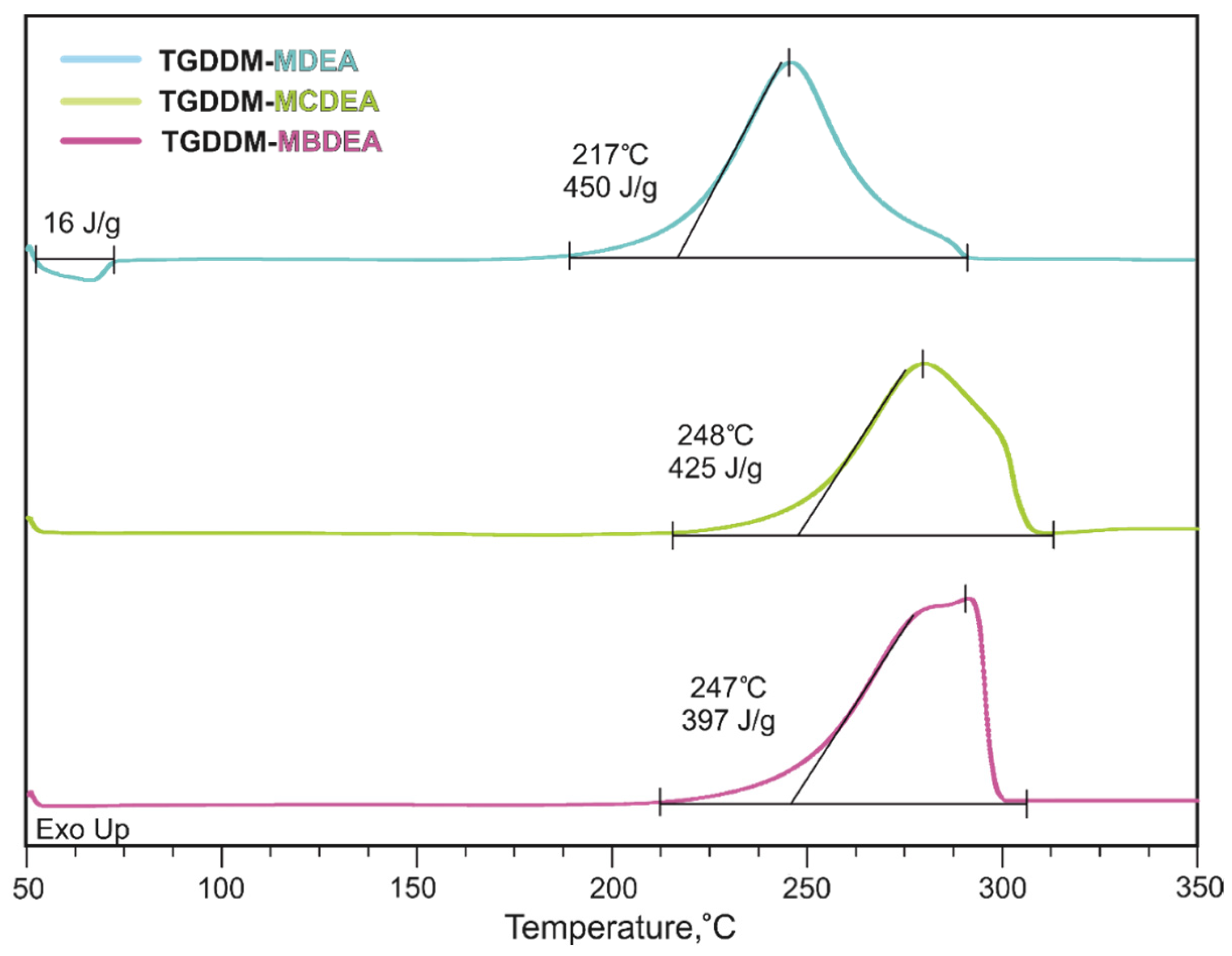

3.2. Properties of Uncured Epoxy Resins

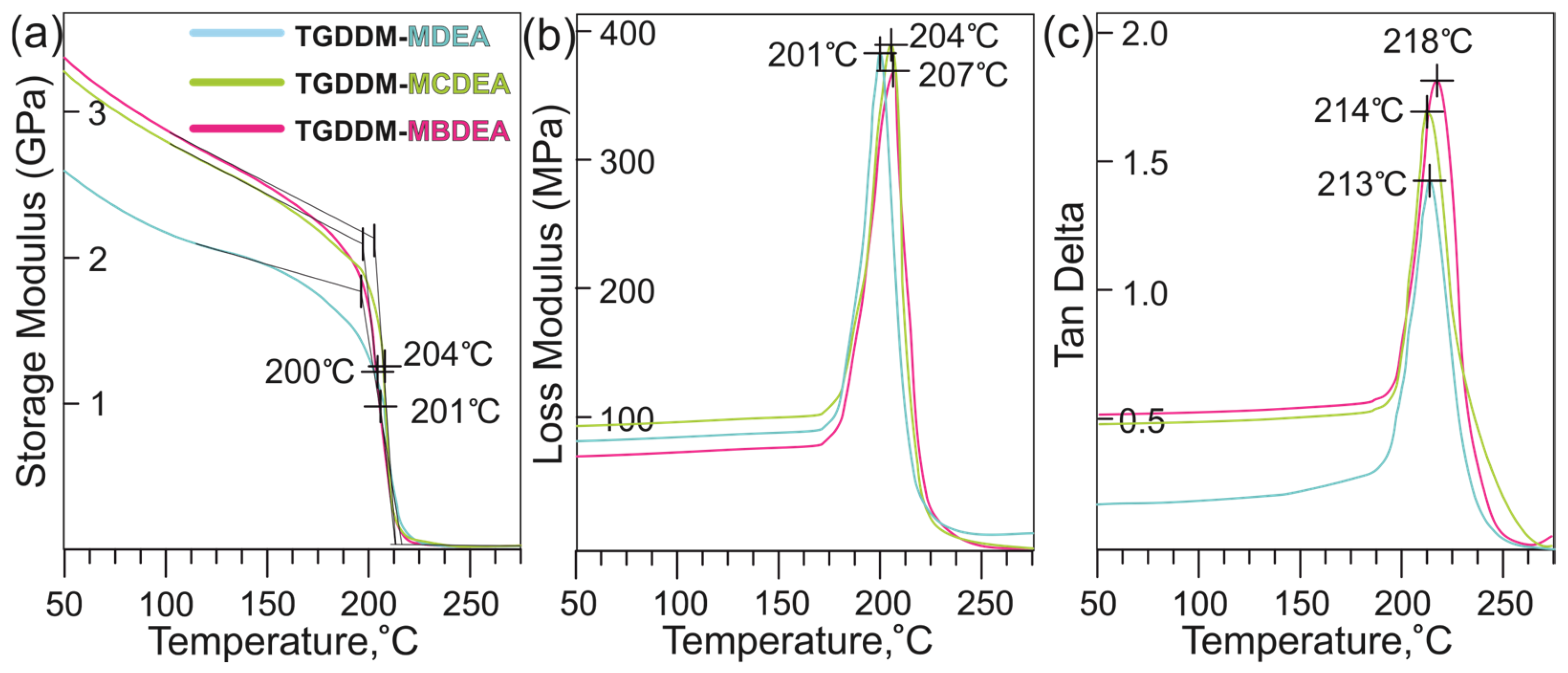

3.3. Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Plastics

3.4. Properties of Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymers Obtained by Vacuum Infusion Method

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFRP | Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Material |

| MDEA | 4,4′-methylenebis(2,6-diethylaniline) |

| MCDEA | 4,4′-methylenebis(3-chloro-2,6-diethylaniline) |

| MBDEA | 4,4′-methylenebis(3-bromo-2,6-diethylaniline) |

| DMA | Dynamic Mechanical Analysis |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| CTE | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion |

| TGDDM | Tetraglycidyl ether of methylenedianiline |

| DMSO-d6 | Deuterated Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

References

- Ahmadi, Z. Nanostructured Epoxy Adhesives: A Review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 135, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shundo, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Tanaka, K. Network Formation and Physical Properties of Epoxy Resins for Future Practical Applications. JACS Au 2022, 2, 1522–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, T.; Haq, F.; Farid, A.; Cheng, L.; Chuah, L.F.; Bokhari, A.; Mubashir, M.; Tang, D.Y.Y.; Show, P.L. The Epoxy Resin System: Function and Role of Curing Agents. Carbon Lett. 2024, 34, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Li, X. A Review of High-Quality Epoxy Resins for Corrosion-Resistant Applications. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2024, 21, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y. A Review on Fundamentals and Strategy of Epoxy-Resin-Based Anticorrosive Coating Materials. Polym. Technol. Mater. 2021, 60, 601–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yu, Q.; Yu, B.; Zhou, F. New Progress in the Application of Flame-Retardant Modified Epoxy Resins and Fire-Retardant Coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Chen, C.; Ye, Y.; Xue, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Xie, X.; Mai, Y.W. Advances on Thermally Conductive Epoxy-Based Composites as Electronic Packaging Underfill Materials—A Review. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2201023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Fan, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z. A Mini-Review of Ultra-Low Dielectric Constant Intrinsic Epoxy Resins: Mechanism, Preparation and Application. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallaev, R.; Pisarenko, T.; Papež, N.; Sadovský, P.; Holcman, V. A Brief Overview on Epoxies in Electronics: Properties, Applications, and Modification. Polymer 2024, 15, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbo, M.K. A Fundamental Review on Composite Materials and Some of Their Applications in Biomedical Engineering. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2021, 33, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.A.M.M.; Santos, M.; Cernadas, T.; Ferreira, P.; Alves, P. Advances in the Development of Biobased Epoxy Resins: Insight into More Sustainable Materials and Future Applications. Int. Mater. Rev. 2022, 67, 119–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, R.; Bartolozzi, A.; Pontefisso, A.; Quaresimin, M.; Zappalorto, M. Improving the Antimicrobial and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Resins via Nanomodification: An Overview. Molecules 2021, 26, 5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Akhtarul Islam, M. Application of Epoxy Resins in Building Materials: Progress and Prospects. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 1949–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodehi, M. Epoxy, Polyester and Vinyl Ester Based Polymer Concrete: A Review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekiač, J.J.; Krbata, M.; Kohutiar, M.; Janík, R.; Kakošová, L.; Breznická, A.; Eckert, M.; Mikuš, P. Comprehensive Review: Optimization of Epoxy Composites, Mechanical Properties, & Technological Trends. Polymers 2025, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.V.; Yadav, A.; Winczek, J. Physical, Mechanical, and Thermal Properties of Natural Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composites for Construction and Automotive Applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, M.N.; Iqbal, A.A. Epoxy Based Nanocomposite Material for Automotive Application—A Short Review. Int. J. Automot. Mech. Eng. 2021, 18, 9127–9140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Raghavender, V.; Joshi, S.; Pooja Vasant, N.; Awasthi, A.; Nagpal, A.; Al-Saleb, A.J.A. Composite Material: A Review over Current Development and Automotive Application. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W.E.; Kumru, B. Polymers as Aerospace Structural Components: How to Reach Sustainability? Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2023, 224, 2300186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.; Vertuccio, L.; Barra, G.; Viscardi, M.; Guadagno, L. Damping Assessment of New Multifunctional Epoxy Resin for Aerospace Structures. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 34, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrehiwet, L.; Abate, E.; Negussie, Y.; Teklehaymanot, T.; Abeselom, E. Application Of Composite Materials In Aerospace & Automotive Industry: Review. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. 2023, 5, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.; Verma, R.; Kumar Garg, R.; Sharma, V. A Critical Review of Recent Advances in the Aerospace Materials. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 113, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, P. A Critical Review: The Modification, Properties, and Applications of Epoxy Resins. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2013, 52, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, I.; Kausar, A.; Anwar, Z.; Muhammad, B. Exploration of Epoxy Resins, Hardening Systems, and Epoxy/Carbon Nanotube Composite Designed for High Performance Materials: A Review. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2016, 55, 312–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, K.K.; Agarwal, G.; Kumar Agarwal, K. A Study of Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Resin in Presence of Different Hardeners. In Proceedings of the Technological Innovation In Mechanical Engineering, Chennai, India, 19–20 September 2019; 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mostovoi, A.S.; Plakunova, E.V.; Panova, L.G. New Epoxy Composites Based on Potassium Polytitanates. Int. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2018, 40, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusek, K. Cross-Linking of Epoxy Resins. In Rubber-Modified Thermoset Resins; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1984; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Kikugawa, G.; Kawagoe, Y.; Shirasu, K.; Kishimoto, N.; Xi, Y.; Okabe, T. Uncovering the Mechanism of Size Effect on the Thermomechanical Properties of Highly Cross-Linked Epoxy Resins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 2593–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, R.; Yuan, X.; Wang, X. Toughening Epoxy Resins: Recent Advances in Network Architectures and Rheological Behavior. Polymer 2025, 334, 128770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, T.; Oya, Y.; Tanabe, K.; Kikugawa, G.; Yoshioka, K. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Crosslinked Epoxy Resins: Curing and Mechanical Properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 80, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Aung, H.H.; Du, B. Curing Regime-Modulating Insulation Performance of Anhydride-Cured Epoxy Resin: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkachuk, A.I.; Zagora, A.G.; Terekhov, I.V.; Mukhametov, R.R. Isophorone Diamine—A Curing Agent for Epoxy Resins: Production, Application, Prospects. A Review. Polym. Sci. Ser. D 2022, 15, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illy, N.; Fu, H.; Mongkhoun, E. Simple/Commercially Available Lewis Acid in Anionic Ring-Opening Polymerization: Powerful Compounds with Multiple Applications in Macromolecular Engineering. ChemCatChem 2025, 17, e202401032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Rashid, N.; Jones, P.; Hussain, R. Thermomechanical Studies of Thermally Stable Metal-Containing Epoxy Polymers from Diglycidyl Ether of Bisphenol A and Amino-Thiourea Metal Complexes. Eur. J. Chem. 2011, 2, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, W.; Feng, Y.; Shi, P.; Wan, L.; Hao, X.; Huang, F.; Qian, J.; Liu, Z. The Effect of the Structure of Aromatic Diamine on High-Performance Epoxy Resins. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leon, A.; Sweat, R.D. Interfacial Engineering of CFRP Composites and Temperature Effects: A Review. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2023, 59, 419–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, R.; Tan, L. Advances in Toughening Modification Methods for Epoxy Resins: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers 2025, 17, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-W.; Wang, Z.-Z.; Liu, L. Synthesis of a novel phosphorus-containing dicyclopentadiene novolac hardener and its cured epoxy resin with improved thermal stability and flame retardancy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 134, 44599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberty, W.; Roberson, M.; Cai, B.; Hendrickson, M. State of the Industry—Resin Infusion: A Literature Review; United States Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Kondrateva, A.; Morozov, O.; Erdni-Goryaev, E.; Afanaseva, E.; Avdeev, V. Improvement of the Impact Resistance of Epoxy Prepregs Through the Incorporation of Polyamide Nonwoven Fabric. Materials 2025, 18, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán, J.I.; Ludueña, L.N.; Stocchi, A.L.; Basso, A.D.; Francucci, G. The Driven Flow Vacuum Infusion Process: An Overview and Analytical Design. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2021, 40, 880–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Huang, K.; Guo, L.; Zheng, T.; Zeng, F. An Automated Vacuum Infusion Process for Manufacturing High-Quality Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Compos. Struct. 2023, 309, 116717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.L.; Li, X.; Park, S.J. Synthesis and Application of Epoxy Resins: A Review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, M.; Yang, X.; Fan, R.; Yue, S.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Q.; He, Y. A Comprehensive Review of Reactive Flame-Retardant Epoxy Resin: Fundamentals, Recent Developments, and Perspectives. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 201, 109976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, O.E.; Bin, H.; Guanghua, M.; Yao, C.; Zhengjia, Z.; Xian, Q.; Xiangyang, W.; Weiwei, F. Review of the Environmental Occurrence, Analytical Techniques, Degradation and Toxicity of TBBPA and Its Derivatives. Environ. Res. 2022, 206, 112594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, B.; Yakubu, S.; Zhu, Q.; Issaka, E.; Zhang, Y.; Adams, M. A Review on Tetrabromobisphenol A: Human Biomonitoring, Toxicity, Detection and Treatment in the Environment. Molecules 2023, 28, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Chaudhary, M.L.; Patel, Y.N.; Chaudhari, K.; Gupta, R.K. Fire-Resistant Coatings: Advances in Flame-Retardant Technologies, Sustainable Approaches, and Industrial Implementation. Polymers 2025, 17, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, J.; Yan, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Han, D. A Review of Status of Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) in China. Chemosphere 2016, 148, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, E.D.; Levchik, S. A Review of Current Flame Retardant Systems for Epoxy Resins. J. Fire Sci. 2004, 22, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. 2,2′,6,6′-TETRABROMO-4,4′-ISOPROPYLIDENEDIPHENOL (TETRABROMOBISPHENOL-A or TBBP-A) Part II—Human Health. In European Union Risk Assessment Report; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.G.; Stapleton, H.M.; Vallarino, J.; McNeely, E.; McClean, M.D.; Harrad, S.J.; Rauert, C.B.; Spengler, J.D. Exposure to flame retardant chemicals on commercial airplanes Exposure to flame retardant chemicals on commercial airplanes. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanovich, A.I.; Hornung, A.; Merz, D.; Seifert, H. The Effect of a Curing Agent on the Thermal Degradation of Fire Retardant Brominated Epoxy Resins. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 85, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luda, M.P.; Balabanovich, A.I.; Zanetti, M.; Guaratto, D. Thermal Decomposition of Fire Retardant Brominated Epoxy Resins Cured with Different Nitrogen Containing Hardeners. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2007, 92, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, D.E.; Morozov, O.S.; Afanasyeva, E.S.; Avdeev, V.V. Synthesis and Crystal Structures of 4,4′-Methylenebis(2,6-Diethylaniline) and 4,4′-Methylenebis(3-Chloro-2,6-Diethylaniline). Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Crystallogr. Commun. 2025, 81, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2863-09; Standard Test Method for Measuring the Minimum Oxygen Concentration to Support Candle-Like Combustion of Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009.

- Gawande, M.B.; Rathi, A.K.; Branco, P.S.; Nogueira, I.D.; Velhinho, A.; Shrikhande, J.J.; Indulkar, U.U.; Jayaram, R.V.; Ghumman, C.A.A.; Bundaleski, N.; et al. Regio- and Chemoselective Reduction of Nitroarenes and Carbonyl Compounds over Recyclable Magnetic Ferrite-Nickel Nanoparticles (Fe3O4-Ni) by Using Glycerol as a Hydrogen Source. Chem. A Eur. J. 2012, 18, 12628–12632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaykumar, G.; Mandal, S.K. An Abnormal N-Heterocyclic Carbene Based Nickel Complex for Catalytic Reduction of Nitroarenes. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 7421–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlali, N.; Dupuy, J.; Dumon, M. Tuning Morphologies of Thermoset/Thermoplastic Blends Part 1: Kinetic Modelling of Epoxy-Amine Reactions Using Amine Mixtures. E-Polymers 2006, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datasheet HexFlow® RTM 6. Available online: https://www.imatec.it/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/RTM6_global.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2016).

- Datasheet T26 ITECMA. Available online: https://itecma.ru/upload/iblock/975/thjysdnb65zsw3310gjz21j65s7x5sy6.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2018).

| Title 1 | MDEA | MCDEA | MBDEA | HexFlow RTM 6 | T26 ITECMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density, g/cm3 | 1.144 | 1.204 | 1.316 | 1.14 | 1.17 |

| Glass transition temperature dry, °C | 200 | 204 | 201 | 202 | 202 |

| Glass transition temperature wet, °C | 175 | 183 | 200 | 160 | 172 |

| Tensile strength σ11+, MPa | 73.9 ± 6.1 | 61.2 ± 12.1 | 62.6 ± 5.5 | 75 | 95 |

| Tensile modulus Ε11+, GPa | 2.92 ± 0.07 | 3.33 ± 0.06 | 3.32 ± 0.12 | 2.89 | 3.1 |

| Relative elongation εp, % | 3.96 ± 0.71 | 2.13 ± 0.51 | 2.09 ± 0.26 | 3.4 | 4–7.2 |

| Poisson’s ratio v | 0.384 ± 0.011 | 0.400 ± 0.016 | 0.402 ± 0.011 | nd | nd |

| Flexural strength, MPa | 131 ± 5 | 118 ± 30 | 96.5 ± 6.7 | 132 | 152 |

| Flexural modulus, GPa | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 3.3 | nd |

| Compressive strength σ11−, MPa | 132.4 ± 3.0 | 157.0 ± 0.6 | 155.8 ± 4.4 | nd | nd |

| Strain energy release, GIC, J/m2 | 663 ± 12 | 832 ± 10 | 1277 ± 55 | 89 | 188 |

| Fracture toughness, KIC, MPa·m1/2 | 0.75 ± 0.10 | 0.93 ± 0.19 | 1.73 ± 0.28 | nd | 0.624 |

| Shore hardness D, HD | 84 | 85 | 85 | nd | nd |

| CTE, ∙106 K−1 | 74 | 71 | 68 | 52.7 | 72 |

| Mass fraction of water absorbed by the sample, % | 2.70 ± 0.01 | 2.06 ± 0.02 | 1.84 ± 0.02 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| LOI, % | 18 | 29 | 34 | nd | nd |

| UL 94 classification | - | V-1 | V-0 | nd | nd |

| MDEA | MCDEA | MBDEA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile strength 0° σ11+, MPa | 810 ± 7 | 913 ± 12 | 960 ± 15 |

| Compression strength 0° σ11−, MPa | 650 ± 20 | 754 ± 13 | 743 ± 33 |

| Tensile modulus 0° E11+, GPa | 72.2 ± 1.0 | 73.3 ± 1.1 | 73.3 ± 1.0 |

| Compression modulus 0° E11−, GPa | 65.8 ± 0.8 | 65.6 ± 1.0 | 65.8 ± 1.3 |

| Shear strength τ12, MPa | 72.5 ± 3.1 | 81.1 ± 2.5 | 81.8 ± 2.2 |

| Shear modulus G12, GPa | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| Interlaminar shear strength τ13, MPa | 64.1 ± 2.2 | 69.8 ± 3.7 | 70.3 ± 3.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kondrateva, A.; Morozov, O.; Terekhov, V.; Kudriashova, E.; Fedorov, A.; Avdeev, V. Synthesis of Halogen-Containing Methylenedianiline Derivatives as Curing Agents for Epoxy Resins and Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Their Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymers. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120687

Kondrateva A, Morozov O, Terekhov V, Kudriashova E, Fedorov A, Avdeev V. Synthesis of Halogen-Containing Methylenedianiline Derivatives as Curing Agents for Epoxy Resins and Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Their Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymers. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):687. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120687

Chicago/Turabian StyleKondrateva, Anastasia, Oleg Morozov, Vladimir Terekhov, Ekaterina Kudriashova, Alexey Fedorov, and Victor Avdeev. 2025. "Synthesis of Halogen-Containing Methylenedianiline Derivatives as Curing Agents for Epoxy Resins and Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Their Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymers" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120687

APA StyleKondrateva, A., Morozov, O., Terekhov, V., Kudriashova, E., Fedorov, A., & Avdeev, V. (2025). Synthesis of Halogen-Containing Methylenedianiline Derivatives as Curing Agents for Epoxy Resins and Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Their Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymers. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120687