Effect of High Carbon Nanotube Content on Electromagnetic Shielding and Mechanical Properties of Cementitious Mortars

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Mix Proportions

2.2. Specimen Preparations

2.3. Electromagnetic Shielding Measurements

3. Results

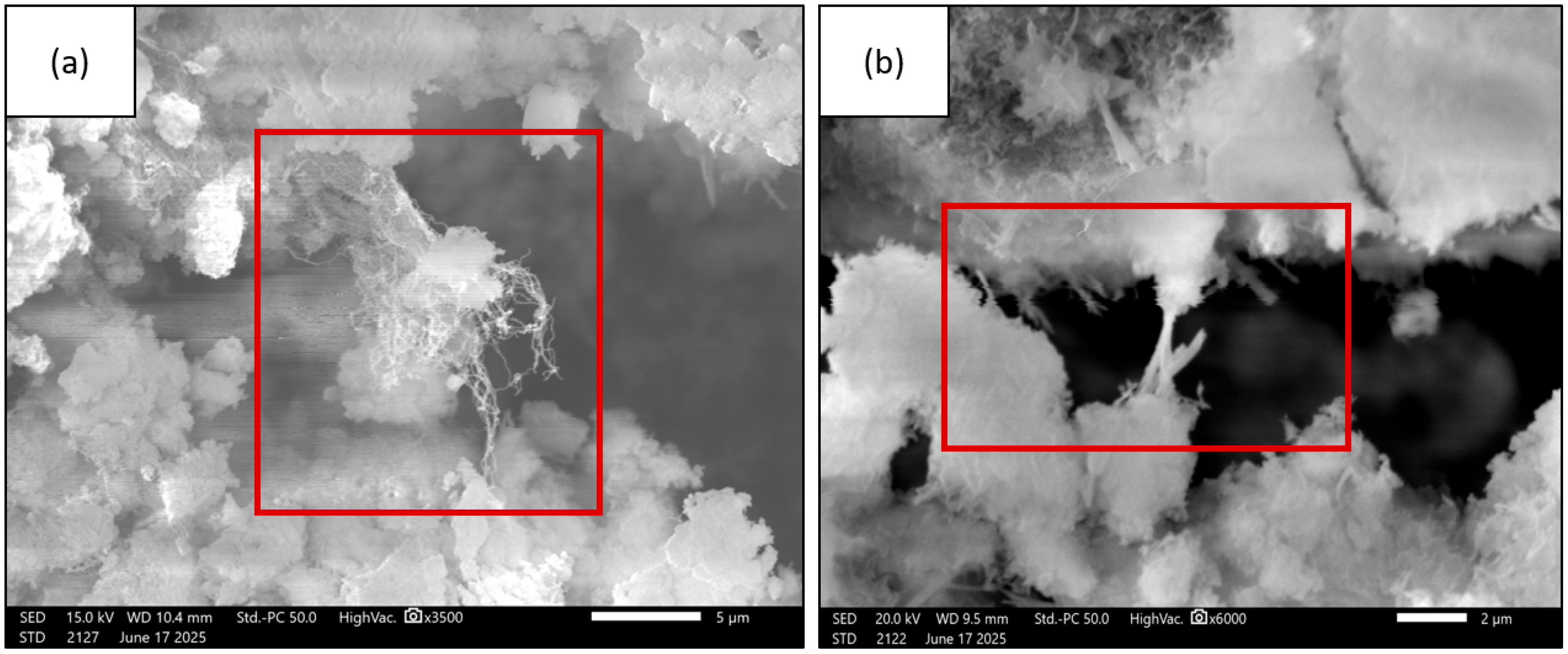

3.1. Microstructure Analysis

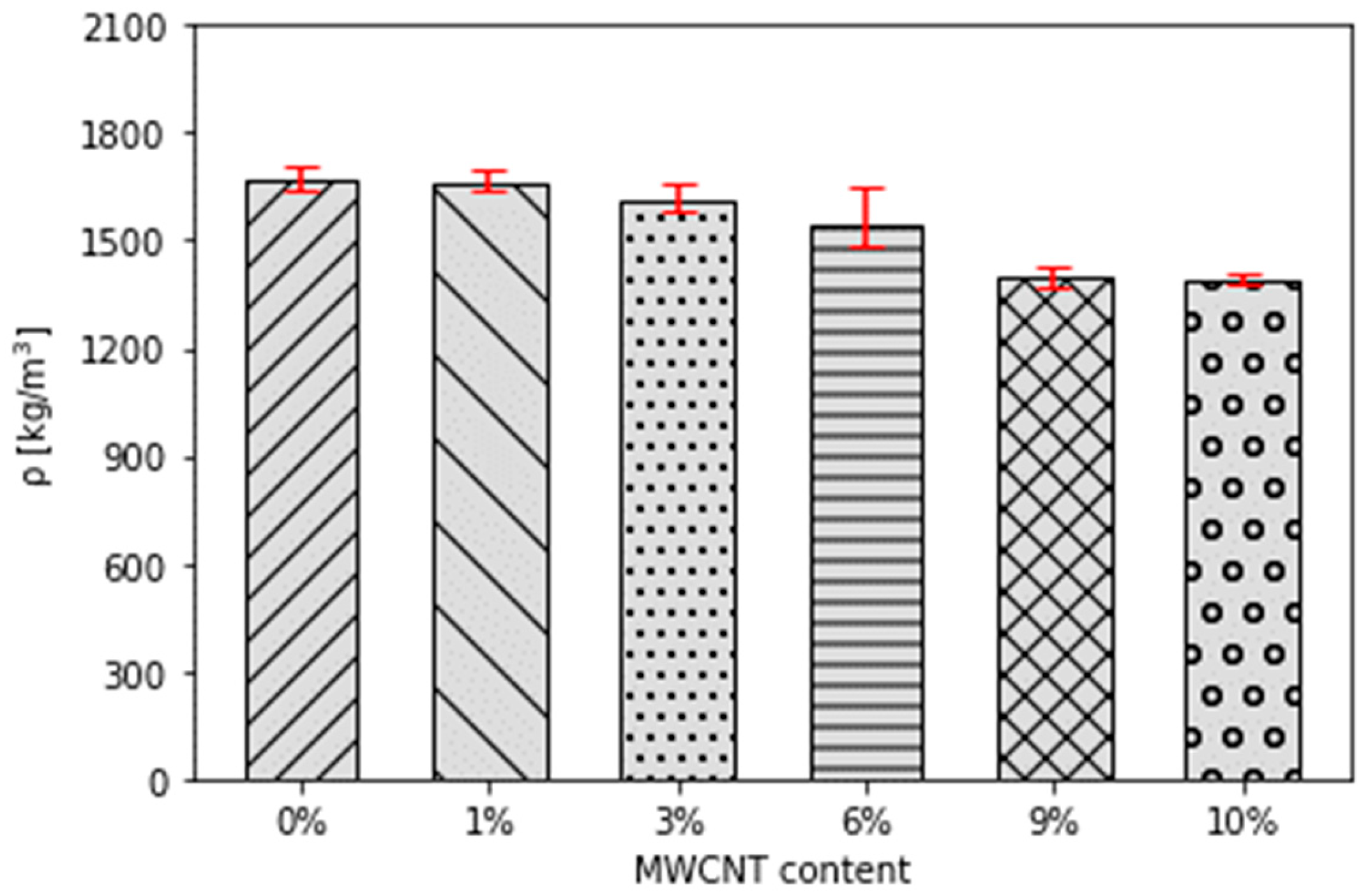

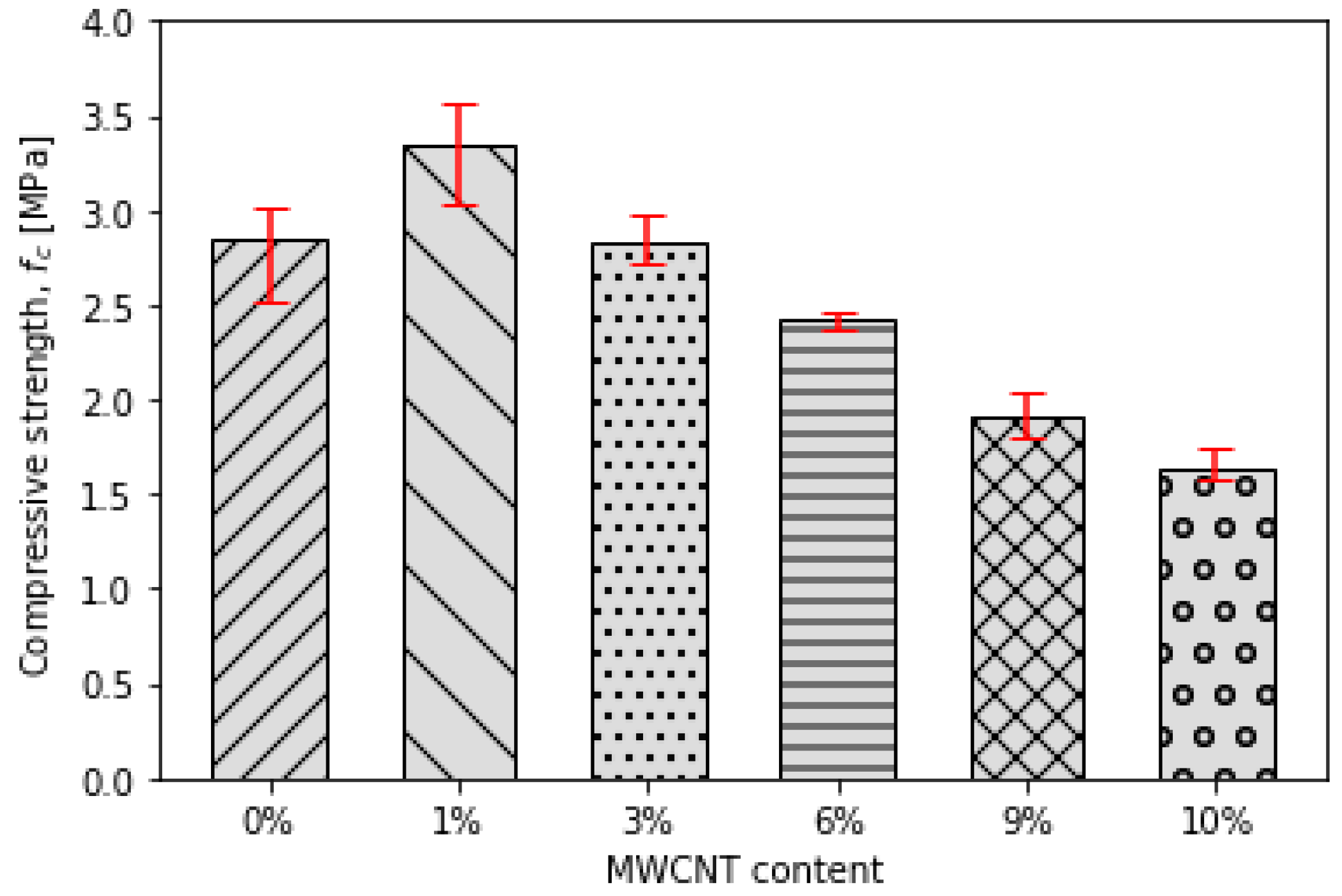

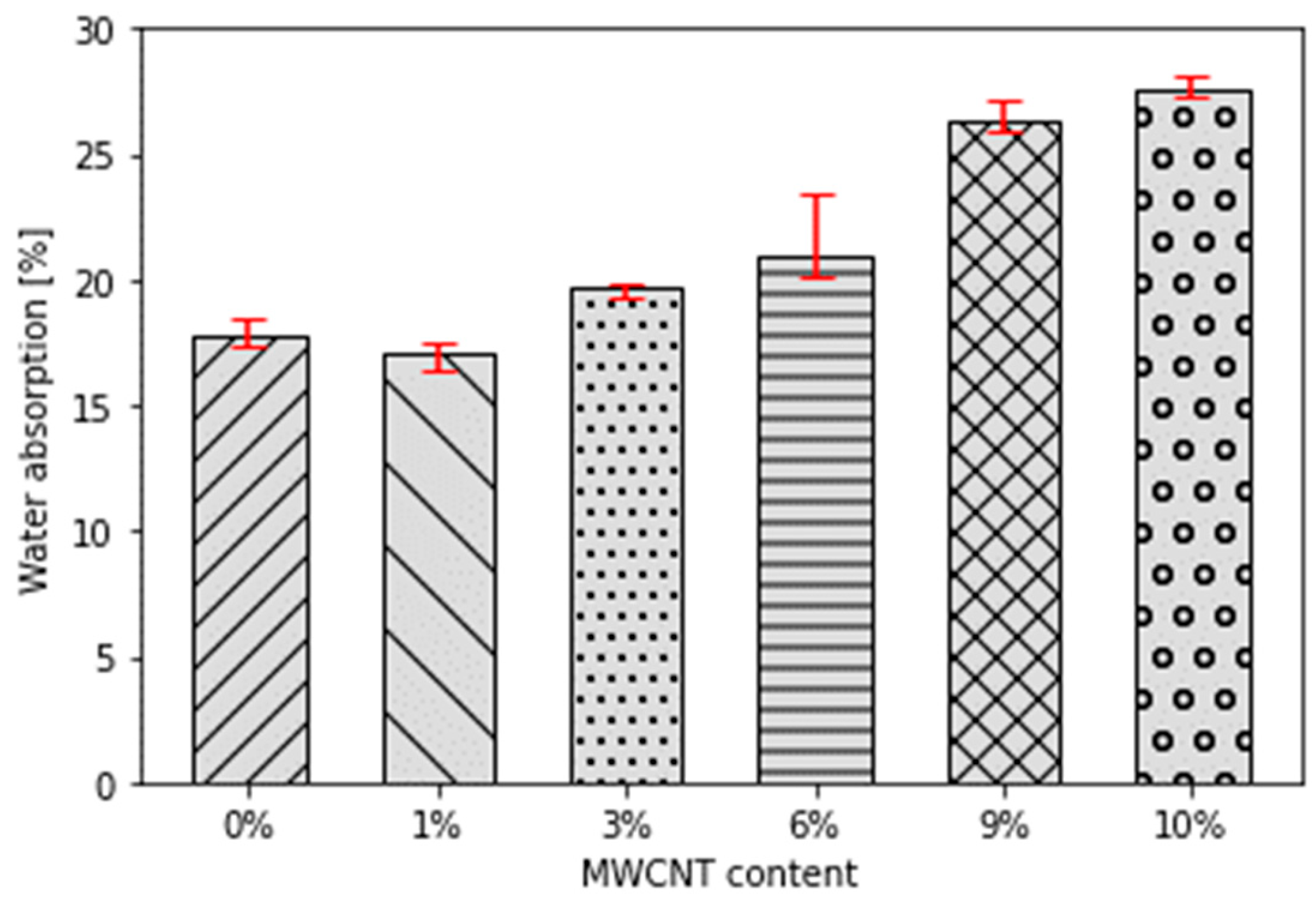

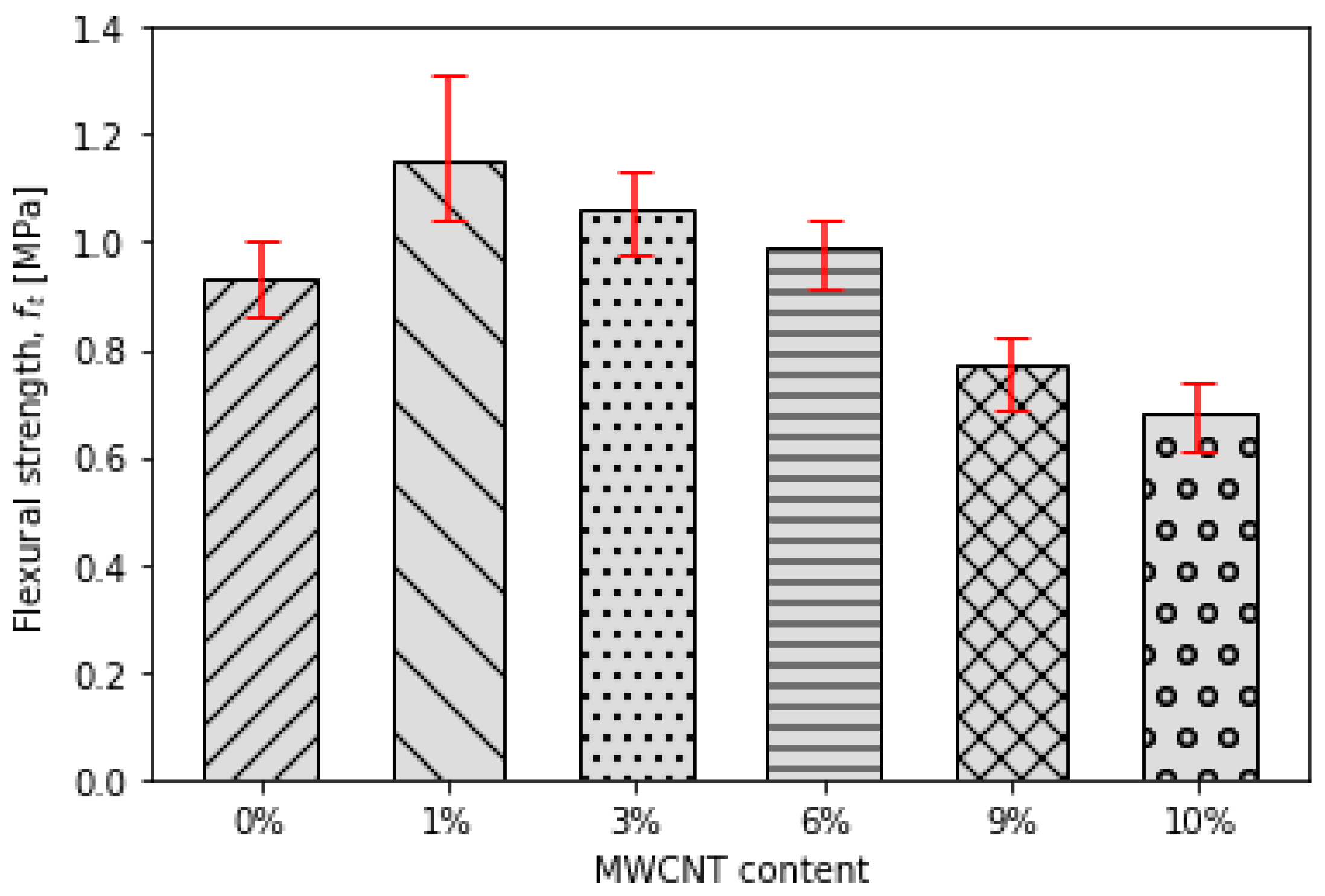

3.2. Mechanical Properties

3.3. Electromagnetic Measurements

- LTE 1800 (1.80–1.88 GHz);

- LTE 2100 (2.11–2.17 GHz);

- LTE 2600 (2.62–2.69 GHz);

- NR 3500 (3.40–3.80 GHz);

- Wifi (5.00 GHz);

- Navigational radar (8.00–9.00 GHz).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EM | Electromagnetic |

| EM SE | Electromagnetic shielding effectiveness |

| MWCNT | Multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| W/B | Water to binder ratio |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| HEMP | High-altitude electromagnetic pulses |

| VNA | Vector network analyzer |

| ITZ | Interfacial transition zone |

References

- Bandara, P.; Carpenter, D.O. Planetary Electromagnetic Pollution: It Is Time to Assess Its Impact. Lancet Planet Health 2018, 2, e512–e514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Venugopal, A.P.; Sutar, P.P.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, Q. Mechanism of Microbial Spore Inactivation through Electromagnetic Radiations: A Review. J. Future Foods 2024, 4, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Standard 299-2006; IEEE Standard Method for Measuring the Effectivness of Electromagnetic Shielding Enclosures. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- Seewooruttun, C.; Mai, T.C.; Corona, A.; Delanaud, S.; de Seze, R.; Bach, V.; Desailloud, R.; Pelletier, A. Electromagnetic Fields from Mobile Phones: A Risk for Maintaining Energy Homeostasis? Ann. Endocrinol. 2025, 86, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McColl, N.; Auvinen, A.; Kesminiene, A.; Espina, C.; Erdmann, F.; de Vries, E.; Greinert, R.; Harrison, J.; Schüz, J. European Code against Cancer 4th Edition: Ionising and Non-Ionising Radiation and Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015, 39, S93–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrdoljak, I.; Brdarić, J.; Rupčić, S.; Marković, B.; Miličević, I.; Mandrić, V.; Varevac, D.; Tatar, D.; Filipović, N.; Szenti, I.; et al. The Effect of Different Nanomaterials Additions in Clay-Based Composites on Electromagnetic Transmission. Materials 2022, 15, 5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrdoljak, I.; Varevac, D.; Miličević, I.; Čolak, S. Concrete-Based Composites with the Potential for Effective Protection against Electromagnetic Radiation: A Literature Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 326, 126919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyıldız, A.; Durmaz, O. Investigating Electromagnetic Shielding Properties of Building Materials Doped with Carbon Nanomaterials. Buildings 2022, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakyi, C.P.; Mpeshe, S.C.; Dida, M.A. Assessment of Public Awareness on the Effects of Exposure to Non-Ionizing Radiation Sources in Tanzania. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2024, 17, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, K.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, H.; Wang, T.; Chi, Y. Uncertainty Assessment of Electromagnetic Exposure Safety for Human Body with Intracranial Artery Stent around EV-WPT Based on K-GRU Surrogate Model. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 125, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.S.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Xiang, P.F.; Le, W.; Li, B.Z. Comparative Study of Volatile Components of Soybean Oil Exposed to Heating, Ionizing and Non-Ionizing Radiation. LWT 2024, 203, 116378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šlouf, M.; Gajdošová, V.; Šloufová, I.; Lukešová, M.; Michálková, D.; Müller, M.T.; Pilař, J. Degradation Processes in Polyolefins with Phenolic Stabilizers Subjected to Ionizing or Non-Ionizing Radiation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 222, 110708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holyer, A.; Stewart, T.; Ashworth, E.T. The Protective Effects of Hyperbaric Oxygen on Ionising Radiation Injury: A Systematic Review. Acta Astronaut. 2025, 232, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, F.; Ogul, H.; Ozkan, I.; Kaçal, M.R.; Agar, O.; Polat, H.; Dilsiz, K. Study on Gamma Radiation Attenuation and Non-Ionizing Shielding Effectiveness of Niobium-Reinforced Novel Polymer Composite. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2022, 54, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yele, M.; Sarula, G.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Jin, C.; et al. Integrated Structural-Functional MXene-GNs/ANF Flexible Composite Film with Enhanced Thermal Conductivity and Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Performance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 241, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, M.; Harichandra, B.P.; Krishna, R.H.; Kumar, M.; Karthikeya, G.S.; Swamy, H.R.; Koul, S.; Nagabhushana, B.M. Enhanced EM Shielding: Synergetic Effect of Zirconium Ferrite, MWCNT, and Graphene in LDPE Polymer Composite to Counteract Electromagnetic Radiation in the X-Band Range. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 699, 134535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Duan, Y.; Liu, S. The Electromagnetic Characteristics of Fly Ash and Absorbing Properties of Cement-Based Composites Using Fly Ash as Cement Replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 27, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Chung, D.D.L. Colloidal Graphite as an Admixture in Cement and as a Coating on Cement for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 1737–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Yan, K.; Chen, H.; Xu, Q.; Zong, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, X. Passive Radiation Heating Smart Fabric with Underwater Sensor and Electromagnetic Wave Absorption. Appl. Mater. Today 2025, 42, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, P.; Singh, J.; Bahel, S.; Dutta, R.; Vig, A.P.; Katnoria, J.K. Assessing Cell Viability and Genotoxicity in Trigonella foenum-graecum L. Exposed to 2100 MHz and 2300 MHz Electromagnetic Field Radiations. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 219, 109311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Lu, M.; Li, G.; Gao, G.; Kang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X. Anti-Impact Electromagnetic Shielding Hydrogel with Solvent-Driven Tunability. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Wu, T.; Mei, X.; Bai, Y.; Guo, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, S.; Mu, J. Polyetheretherketone-Based Foam with Low Reflectivity and High Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Effectiveness Suitable for Harsh Service Environments. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 165917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikinka, E.; Whittaker, T.; Synaszko, P.; Whittow, W.; Zhou, G.; Dragan, K. The Influence of Impact-Induced Damage on Electromagnetic Shielding Behaviour of Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 187, 108464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvente, I.; Núñez, M.I. Is the Sustainability of Exposure to Non-Ionizing Electromagnetic Radiation Possible? Med. Clin. 2024, 162, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyaya, C.; Upadhyaya, T.; Patel, I. Attributes of Non-Ionizing Radiation of 1800 MHz Frequency on Plant Health and Antioxidant Content of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Plants. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2022, 15, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Potential Dangers of Electromagnetic Fields and Their Effect on the Environment Parliamentary Assembly. Available online: https://pace.coe.int (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Wang, H.; Tong, J.; Cao, Y. Non-Ionizing Radiation-Induced Cellular Senescence and Age-Related Diseases. Radiat. Med. Prot. 2024, 5, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motchidlover, L.; Sari-Minodier, I.; Sunyach, C.; Metzler-Guillemain, C.; Perrin, J. Impact of Non-Ionising Radiation of Male Fertility: A Systematic Review. Fr. J. Urol. 2025, 35, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostoff, R.N.; Heroux, P.; Aschner, M.; Tsatsakis, A. Adverse Health Effects of 5G Mobile Networking Technology under Real-Life Conditions. Toxicol. Lett. 2020, 323, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Wei, Q.; Ye, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Shen, R.; Li, Z.; Lu, S. Liquid Metal Flexible Multifunctional Sensors with Ultra-High Conductivity for Use as Wearable Sensors, Joule Heaters and Electromagnetic Shielding Materials. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 291, 112064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.A.; Radiman, S.; Majid, A.A.; Yasir, M.S.; Yahaya, R.; Mohamed, F.; Noor, M.Z.B.M.; Umar, S.R.; Pozi, F. Policy Development, Monitoring and Subject Reintroduction of Nonionising Radiation in Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 59, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Chung, D.D.L. Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Reaching 70 DB in Steel Fiber Cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Qing, S.; Lyu, P.; Ren, J.; Ran, Q.; Hou, J.; Wang, Z.; Xia, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; et al. Multifunctional Porous Carbon Fibers-Based Porous Stacking for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Carbon 2025, 233, 119907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, I.W.; Lee, H.K. Synergistic Effect of MWNT/Fly Ash Incorporation on the EMI Shielding/Absorbing Characteristics of Cementitious Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 115, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Dai, M.; Fang, B.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, S.; Huang, Z.; Xue, J.; Li, X.; Shi, S.; Cheng, F. Assembly of PAN/Gr@MWCNTs/CoFe2O4 Multilayer Composite Films for High-Efficiency Electromagnetic Shielding and Joule Heating. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 262, 111081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, E.C.; Calisir, M.D.; Selcuk, S.; Gungor, M.; Acma, M.E. Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Using Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 317, 129165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Depci, T.; Bahceci, E.; Karaaslan, M.; Akgol, O.; Sevim, U.K. Production of New Electromagnetic Wave Shielder Mortar Using Waste Mill Scales. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 242, 118028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushnood, R.A.; Ahmad, S.; Savi, P.; Tulliani, J.M.; Giorcelli, M.; Ferro, G.A. Improvement in Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Effectiveness of Cement Composites Using Carbonaceous Nano/Micro Inerts. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 85, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglie, F.; Micheli, D.; Laurenzi, S.; Marchetti, M.; Mariani Primiani, V. Electromagnetic Shielding Performance of Carbon Foams. Carbon 2012, 50, 1972–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakilas, V.; Perman, J.A.; Tucek, J.; Zboril, R. Broad Family of Carbon Nanoallotropes: Classification, Chemistry, and Applications of Fullerenes, Carbon Dots, Nanotubes, Graphene, Nanodiamonds, and Combined Superstructures. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4744–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Guo, Z.; Han, Y.; Zhang, T. Electromagnetic Wave Absorbing Properties of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube/Cement Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 46, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Haq, R.S.U.; Ahmed, S.; Siddiqui, F.; Yi, J. Recent Advances in Carbon Nanotubes, Graphene and Carbon Fibers-Based Microwave Absorbers. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 970, 172625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Han, B. Multifunctional Cement-Based Materials Modified with Electrostatic Self-Assembled CNT/TiO2 Composite Filler. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 238, 117787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Feng, H. The Growth of In-Situ CNTs on Slag to Enhance Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Effectiveness of Cement-Based Composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.N.; Jang, D.; Lee, H.K.; Nam, I.W. Influence of Carbon Fiber Additions on the Electromagnetic Wave Shielding Characteristics of CNT-Cement Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafogianni, P.; Dassios, K.; Tsakiroglou, C.D.; Matikas, T.E.; Barkoula, N.M. Effect of CNT Addition and Dispersive Agents on the Transport Properties and Microstructure of Cement Mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 197, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijima, S. Helical Microtubules of Graphitic Carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Lee, Y.S.; Hong, S.G.; Moon, J. Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) in Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC): Dispersion, Mechanical Properties, and Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) Shielding Effectiveness (SE). Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 131, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaipanich, A.; Nochaiya, T.; Wongkeo, W.; Torkittikul, P. Compressive Strength and Microstructure of Carbon Nanotubes–Fly Ash Cement Composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, G.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S. Piezoresistive Properties of Well-Dispersed Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) Modified Cement Paste. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Conference on Electromagnetics in Advanced Applications; Politecnico di Torino; Istituto di Elettronica e di Ingegneria dell’Informazione e delle Telecomunicazioni; Istituto Superiore Mario Boella; IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society; Torino Wireless Foundation; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers; IEEE-APS Topical Conference on Antennas and Propagation in Wireless Communications. Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Electromagnetics in Advanced Applications (ICEAA): ICEAA ’15, 17th Edition, 7–11 September 2015, Torino, Italy; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- EN 197-1:2012; Cement–Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- Chung, D.D.L. Materials for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 255, 123587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, S.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Han, B. Electromagnetic Wave-Absorbing Property and Mechanism of Cementitious Composites with Different Types of Nano Titanium Dioxide. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04020073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Han, B.; Yu, X.; Dong, S.; Zhang, L.; Don, X.; Ou, J. Effect of Nano-Titanium Dioxide on Mechanical and Electrical Properties and Microstructure of Reactive Powder Concrete. Mater. Res. Express 2017, 4, 095008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.; Ping, C.S.; Leong, K.Y. Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Performances of MWCNT in Concrete Composites. Solid State Phenom. 2017, 266, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4935-18; Standard Test Method for Measuring the Electromagnetic Shielding Effectivness of Planar Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM E1851-15; Standard Test Method for Electromagnetic Shielding Effectivness of Durable Rigid Wall Relocatable Structures. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- MIL-STD-188-125-1; High-Altitude Electromagnetic Pulse (HEMP) Protection for Ground-Based C4l Facilities Performing Critical, Time-Urgent Missions—Part 1: Fixed Facilities. Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Vrdoljak, I. Test Methods for Measuring EM Radiation Shielding. In Proceedings of the 14th Conference of Civil and Environmental Engineering for Phd Students and Young Scientists: Young Scientist 2022 (Ys22), Slovak Paradise, Slovakia, 27–29 June 2022; Volume 2887, p. 020005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.K.; Lee, C.Y.; Jeong, C.K.; Lee, D.E.; Kim, K.; Joo, J. Method and Apparatus to Measure Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Efficiency and Its Shielding Characteristics in Broadband Frequency Ranges. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2003, 74, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, D.; Aslani, F.; Ma, G. Effect of Water to Cement Ratio, Fly Ash, and Slag on the Electromagnetic Shielding Effectiveness of Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 256, 119409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, D.; Vricella, A.; Pastore, R.; Delfini, A.; Bueno Morles, R.; Marchetti, M.; Santoni, F.; Bastianelli, L.; Moglie, F.; Mariani Primiani, V.; et al. Electromagnetic Properties of Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Concrete Composites for Frequency Selective Shielding Structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 131, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Gupta, B.K.; Mishra, M.; Govind; Chandra, A.; Mathur, R.B.; Dhawan, S.K. Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube/Cement Composites with Exceptional Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Properties. Carbon 2013, 56, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Han, B.; Yu, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, D. Carbon Nanotubes Reinforced Reactive Powder Concrete. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 112, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1097-6:2022; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- Hawreen, A.; Bogas, J.A.; Kurda, R. Mechanical Characterization of Concrete Reinforced with Different Types of Carbon Nanotubes. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2019, 44, 8361–8376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Unit | Value 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Average diameter | Nanometers | 9.5 |

| Average length | Microns | 1.5 |

| Carbon purity | % | 90 |

| Metal oxide content | % | 10 |

| Specific surface area | m2/g | 250–300 |

| Mixture | M0 | M1 | M3 | M6 | M9 | M10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand [g] | 9658.3 | 9658.3 | 9658.3 | 9658.3 | 9658.3 | 9658.3 |

| Lime [g] | 765.3 | 740.57 | 691.12 | 616.92 | 543.16 | 518 |

| Cement [g] | 1707.4 | 1707.4 | 1707.4 | 1707.4 | 1707.4 | 1707.4 |

| NC7000 [g] | 0 | 24.73 | 74.18 | 148.36 | 222.54 | 247.3 |

| Water [g] | 2803 | 2803 | 3007 | 3007 | 3211 | 3211 |

| W/B [%] | 1.13 | 1.14 | 1.25 | 1.29 | 1.43 | 1.44 |

| Measured Frequency | Mean Values of S21 Parameter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Frequency Span [GHz] | M0 | M1 | M3 | M6 | M9 | M10 |

| LTE 1800 | 1.80–1.88 | −15.79 | −16.02 | −15.98 | −17.64 | −22.57 | −22.53 |

| LTE 2100 | 2.11–2.17 | −26.68 | −26.42 | −23.71 | −29.73 | −35.28 | −34.83 |

| LTE 2600 | 2.62–2.69 | −16.41 | −18.26 | −26.22 | −29.27 | −33.24 | −33.92 |

| NR 3500 | 3.40–3.80 | −18.64 | −17.65 | −20.28 | −25.11 | −29.64 | −30.35 |

| Wifi | 5.00 | −22.99 | −23.05 | −26.67 | −32.77 | −39.29 | −39.57 |

| Navigational radar | 8.00–9.00 | −24.12 | −24.82 | −31.70 | −42.79 | −51.73 | −51.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vrdoljak, I.; Miličević, I.; Romić, O.; Bušić, R. Effect of High Carbon Nanotube Content on Electromagnetic Shielding and Mechanical Properties of Cementitious Mortars. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120664

Vrdoljak I, Miličević I, Romić O, Bušić R. Effect of High Carbon Nanotube Content on Electromagnetic Shielding and Mechanical Properties of Cementitious Mortars. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):664. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120664

Chicago/Turabian StyleVrdoljak, Ivan, Ivana Miličević, Oliver Romić, and Robert Bušić. 2025. "Effect of High Carbon Nanotube Content on Electromagnetic Shielding and Mechanical Properties of Cementitious Mortars" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120664

APA StyleVrdoljak, I., Miličević, I., Romić, O., & Bušić, R. (2025). Effect of High Carbon Nanotube Content on Electromagnetic Shielding and Mechanical Properties of Cementitious Mortars. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120664