Flexural Performance of Pre-Cracked UHPC with Varying Fiber Contents and Fiber Types Exposed to Freeze–Thaw Cycles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Test Setup and Procedures

3.1. UHPC Freeze–Thaw Testing

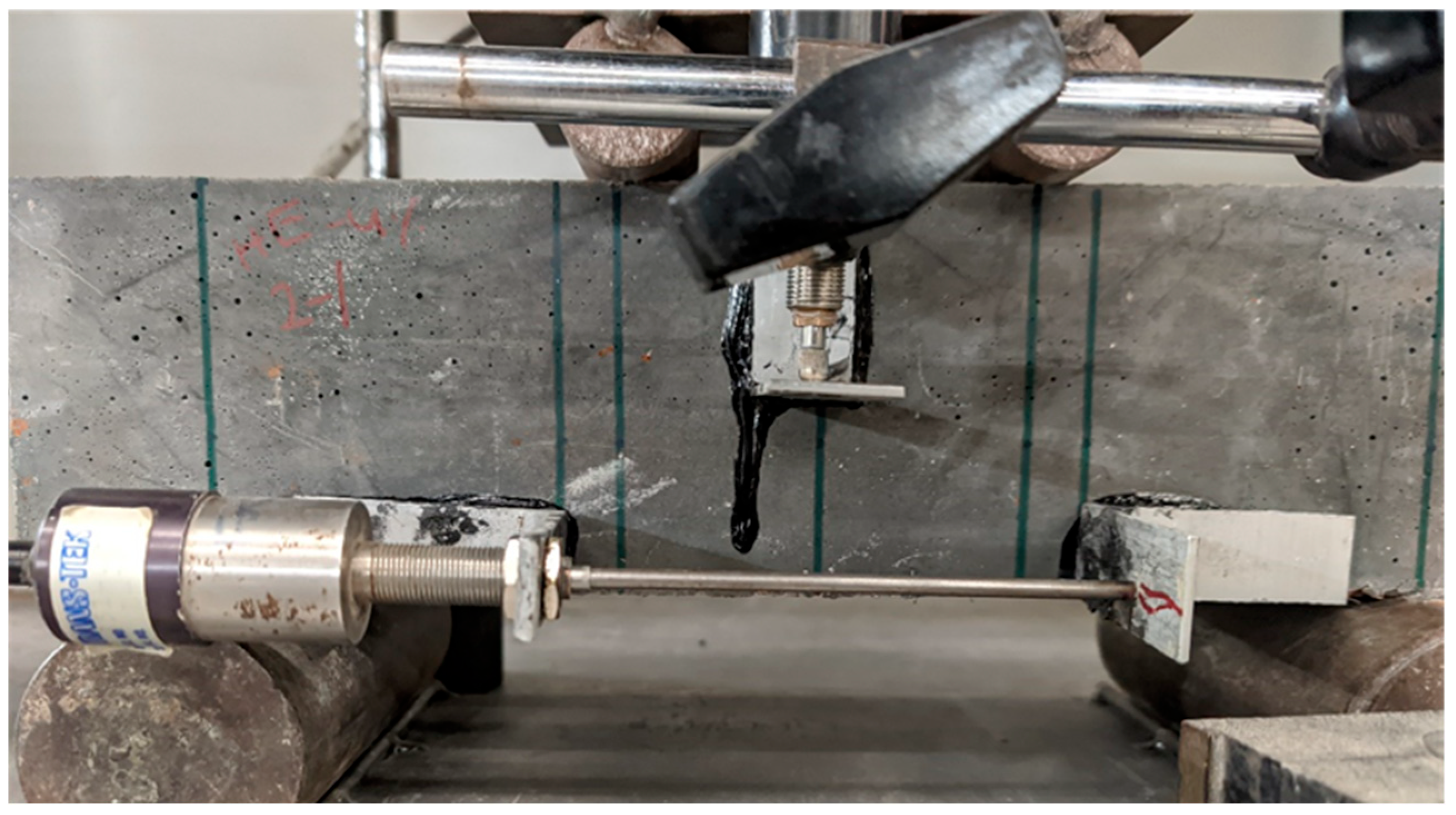

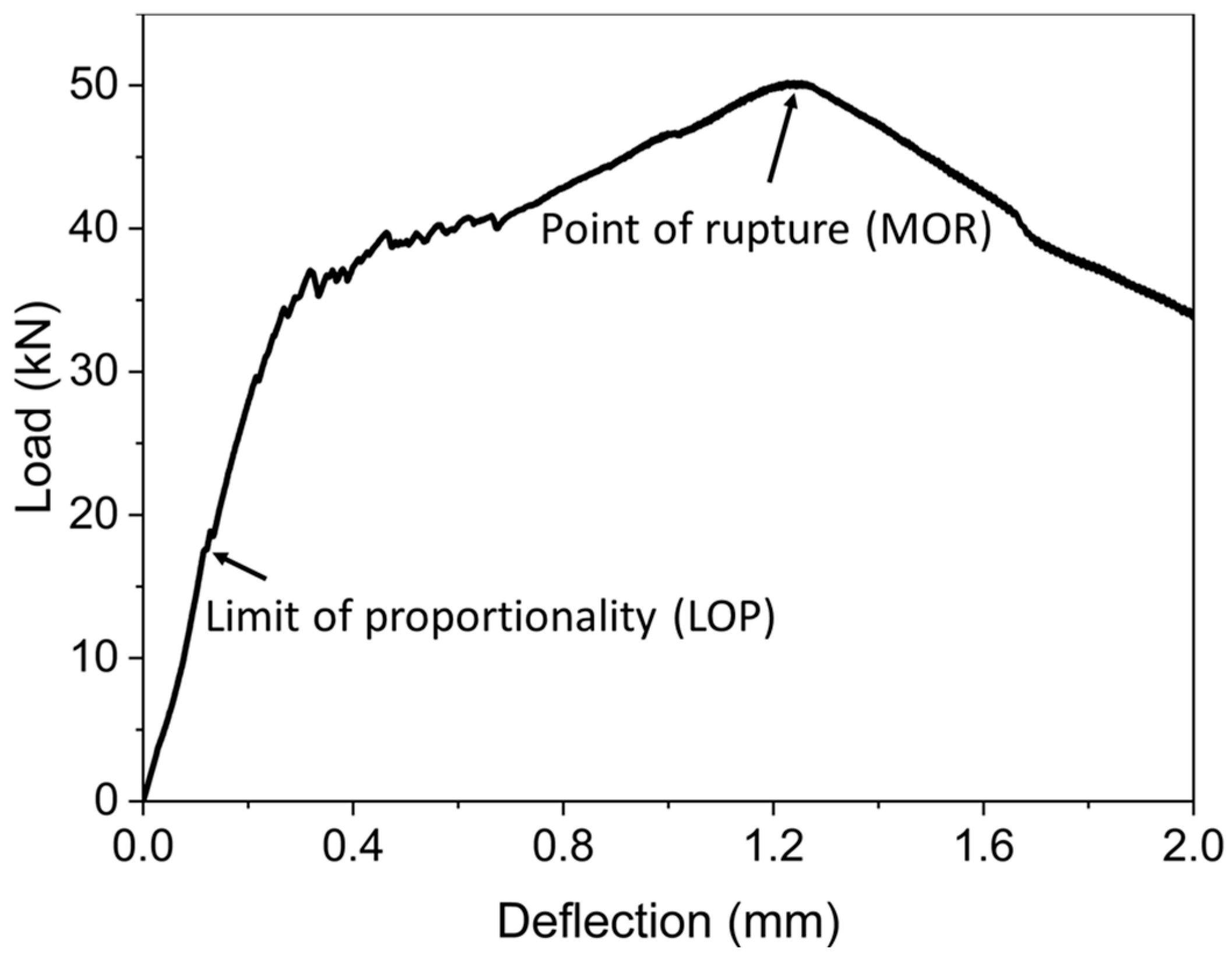

3.2. Flexural Strength Testing

4. Results

4.1. Overview

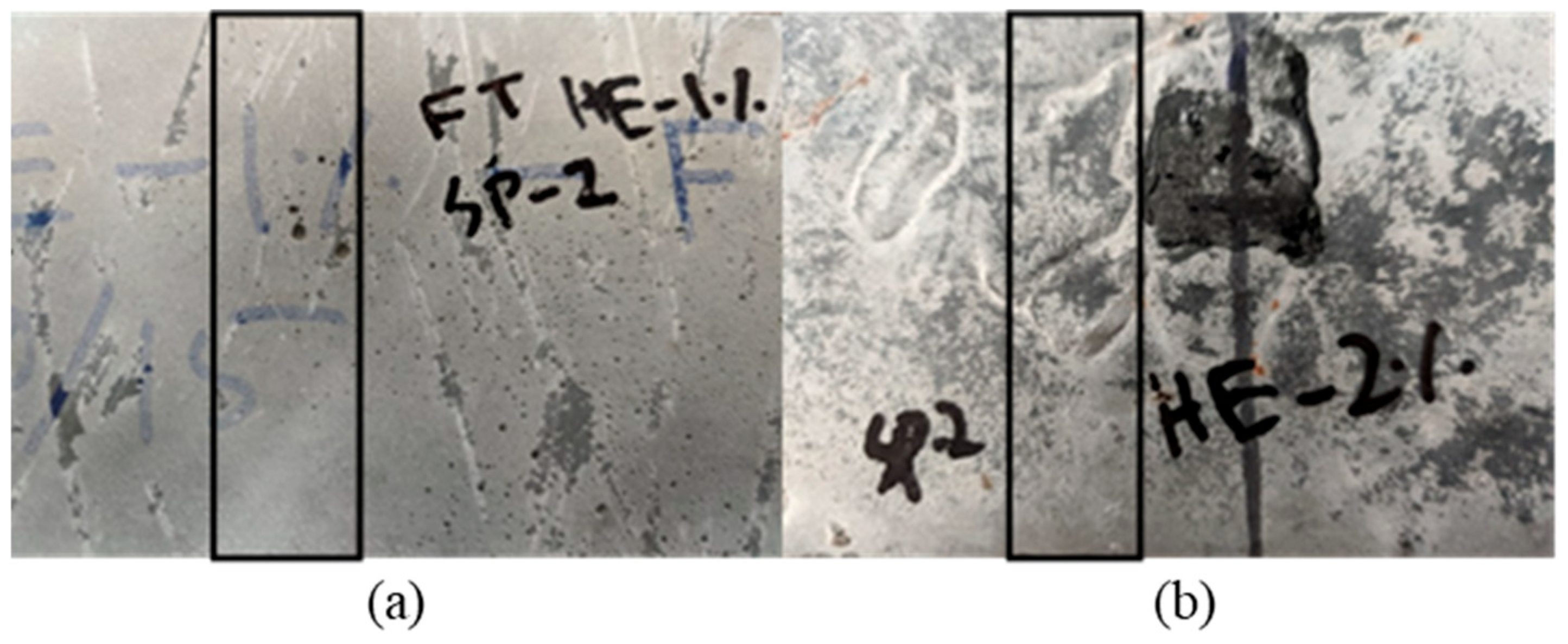

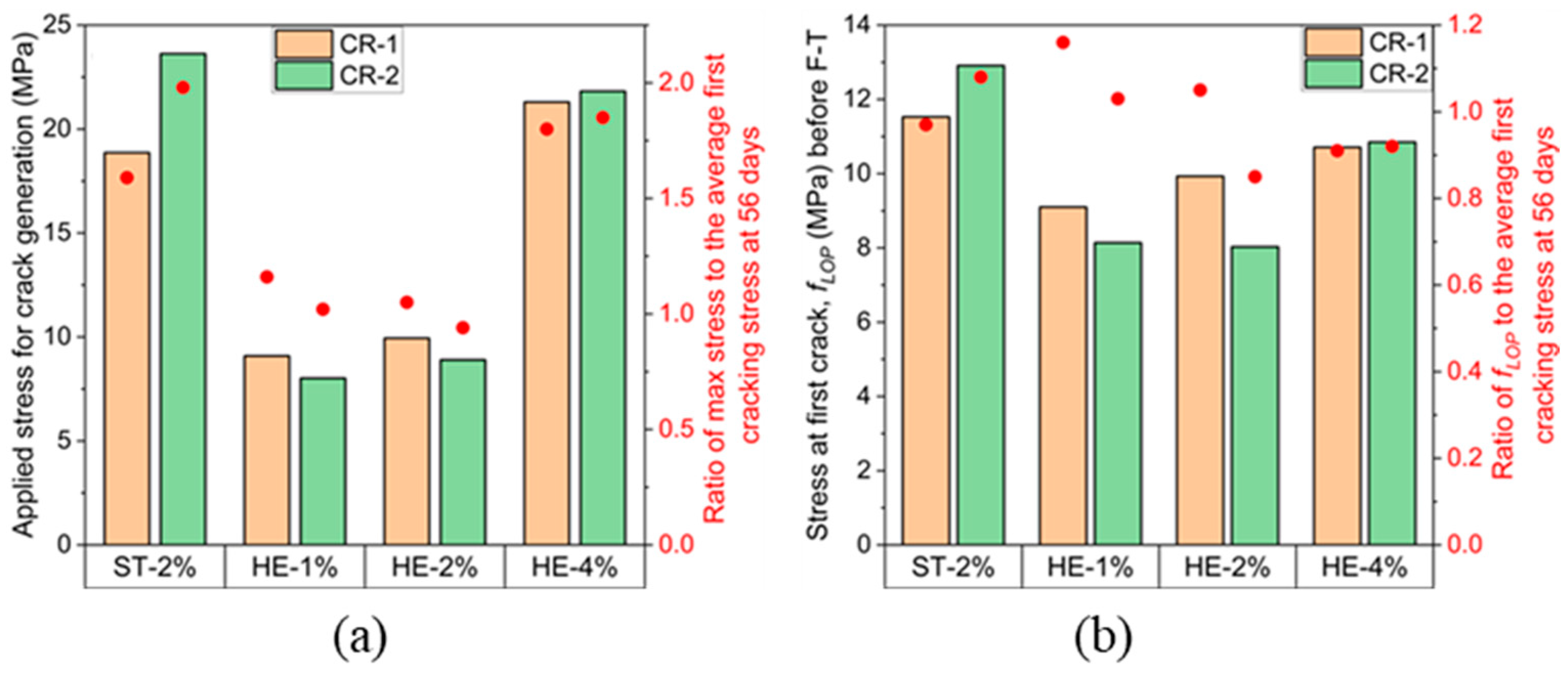

4.1.1. Crack Generation in the Pre-Cracked Specimens

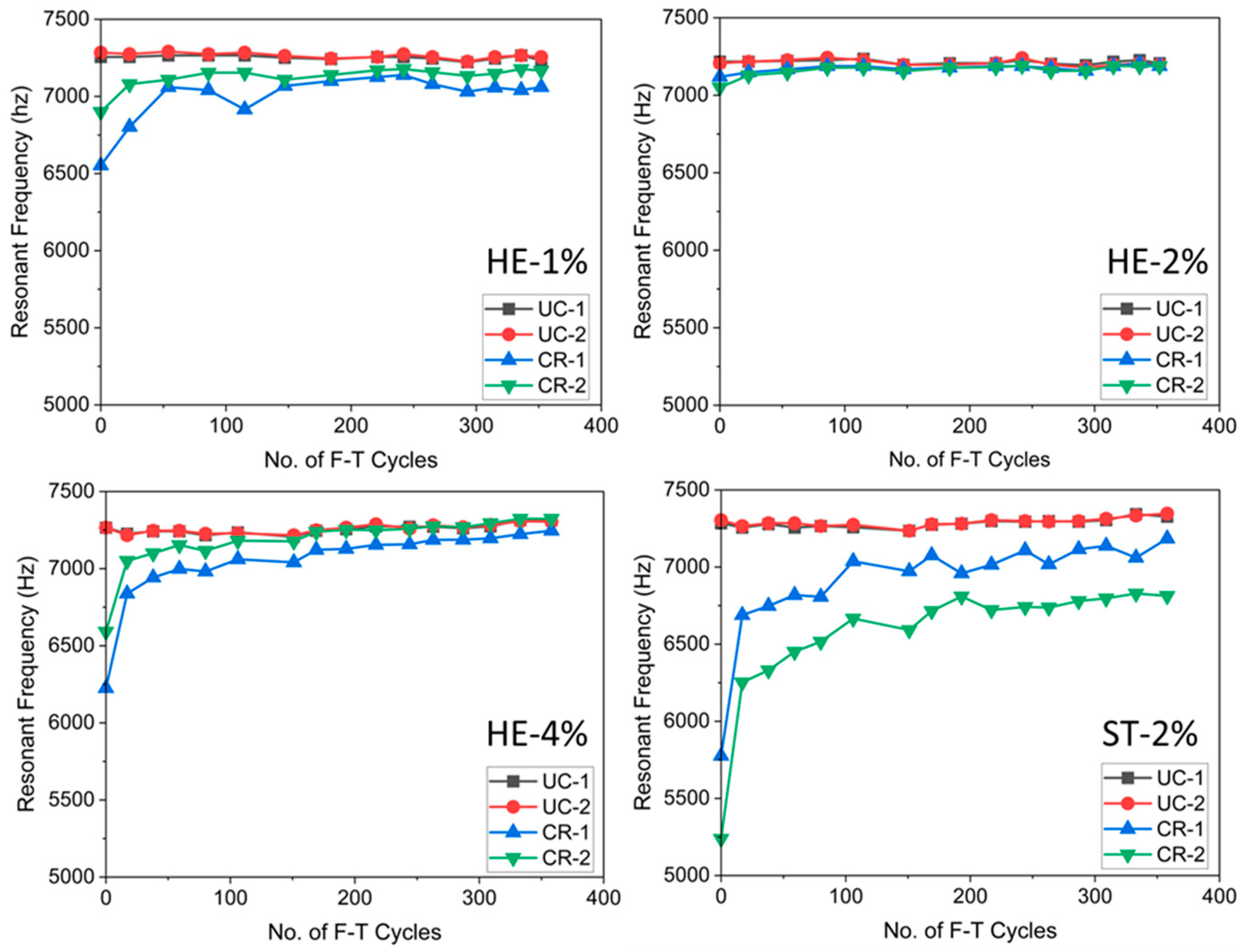

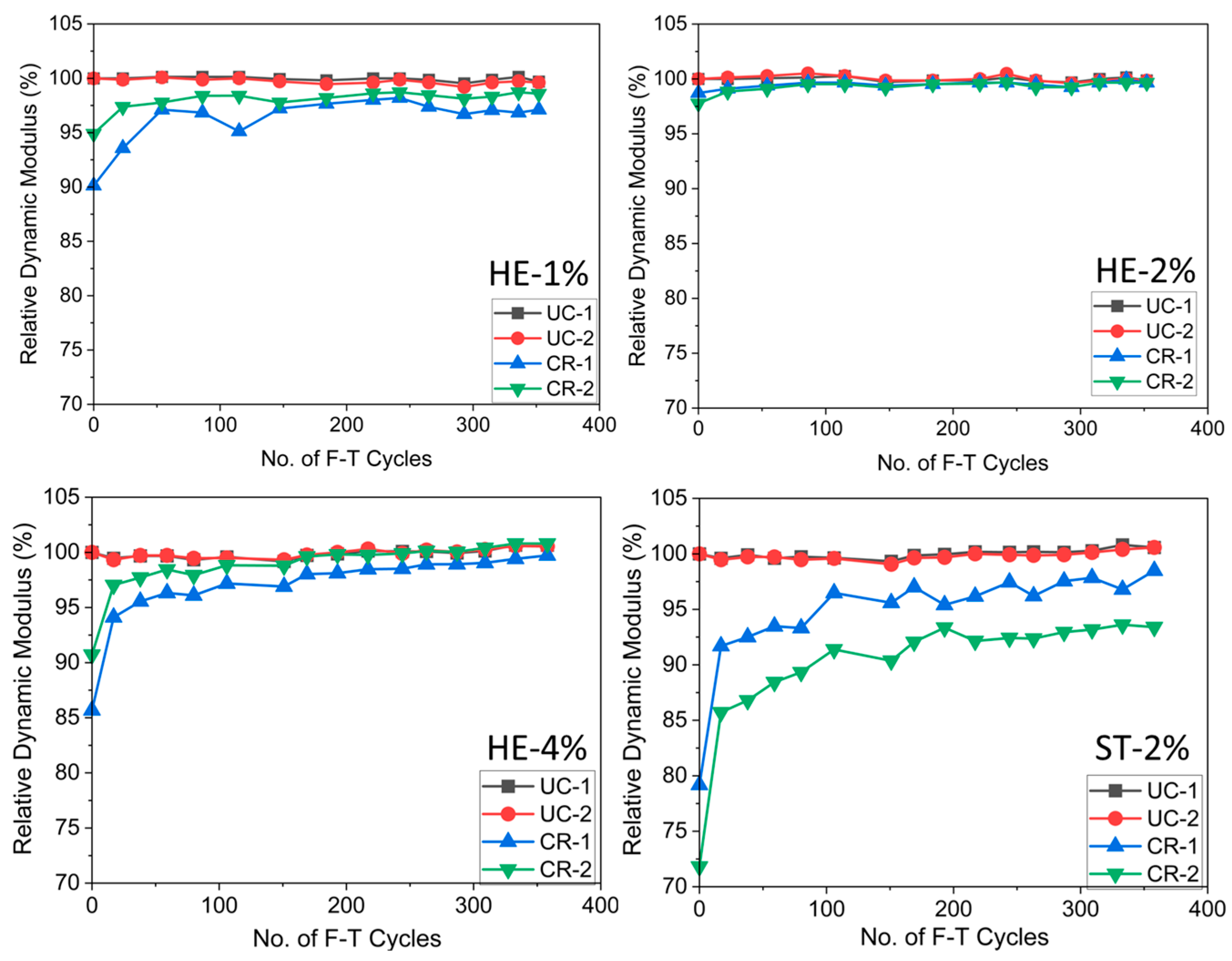

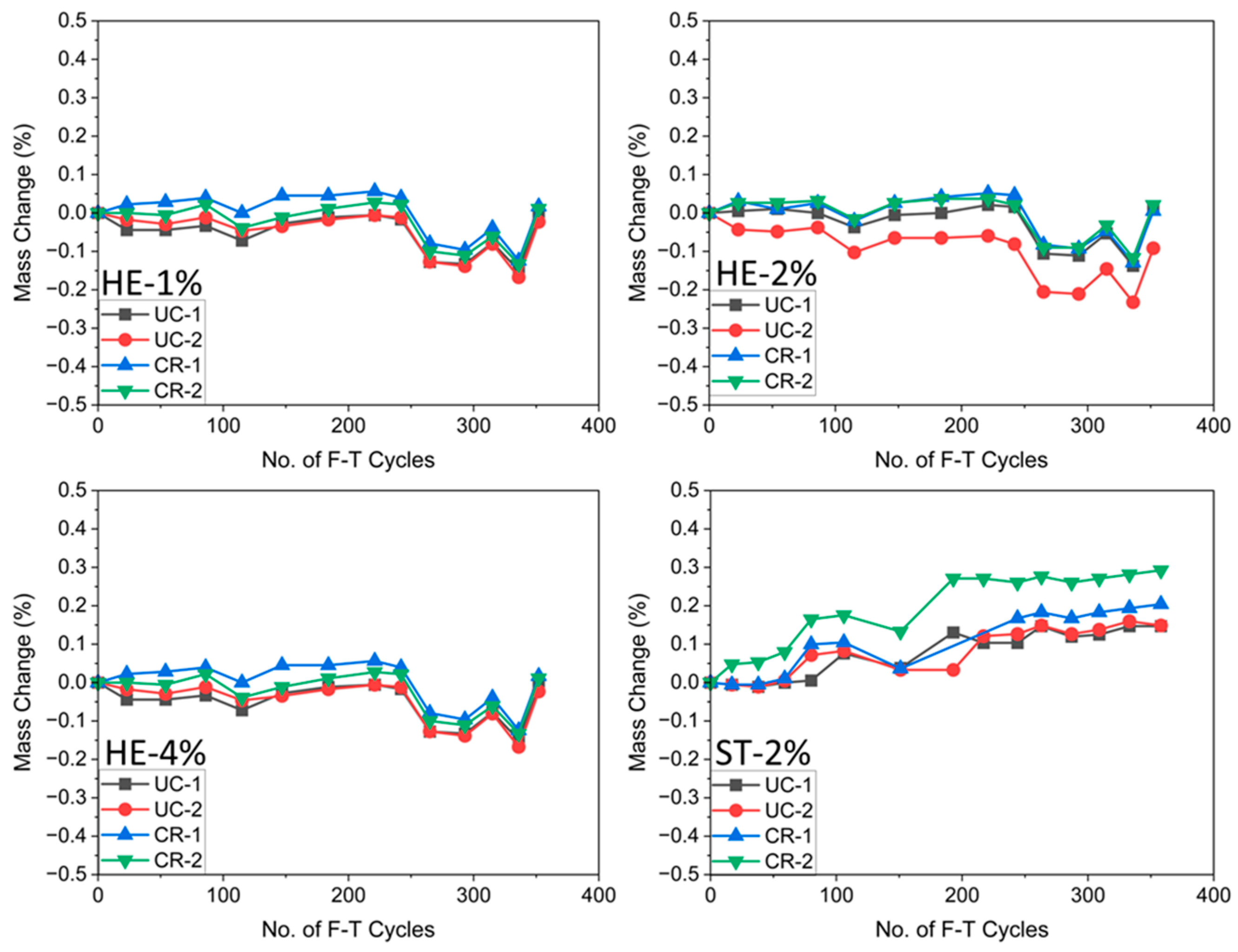

4.1.2. Effect of Freeze–Thaw Cycles

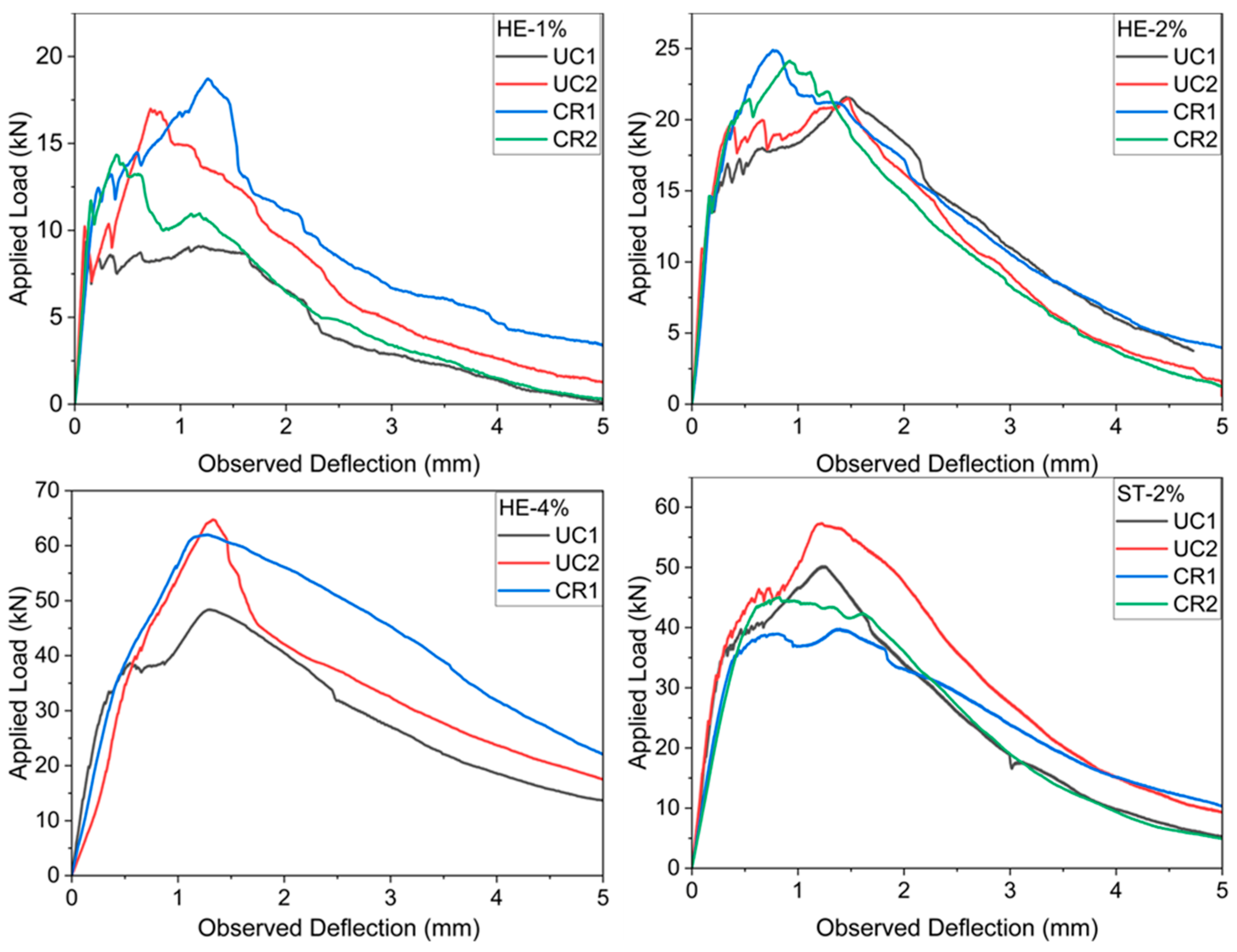

4.2. Flexural Strength

5. Conclusions

- Pre-cracked UHPC shows self-healing and crack sealing properties during freeze–thaw exposure in a saturated condition based on resonant frequency. It should be noted that additional microstructural analysis is needed to confirm the extent of the additional reaction over time.

- Resonant frequency showed no deterioration of the UHPC specimens due to the freeze–thaw cycles. Moreover, no significant scaling was observed from mass tracking of the samples. The pre-cracked specimens showed gains in resonant frequency and mass during freeze–thaw testing, whereas these properties were unchanged for the uncracked specimens.

- The uncracked UHPC lost first cracking strength likely due to the generation of microcracks as this is not influenced by fiber inclusions. Pre-cracked UHPC samples did not show a reduction in first-cracking strength as the fiber interaction was already active for these specimens.

- Generation of microcracks due to freeze–thaw compromises the mortars’ capacity to resist crushing and anchor hooked end fibers. The final failure mode of specimens with HE fibers is damage to the matrix due to the shape of the fibers. Because of that, the HE-1% and HE-2% specimens showed a significant drop in ultimate flexural capacity after freeze–thaw exposure. However, HE-4% specimens having more than sufficient fibers bridging the cracks did not suffer this reduction, but had fiber distribution issues leading to inconsistent results. The ST-2% specimens’ final failure mode was fiber pullout, and no significant drop in ultimate flexural capacity was observed after freeze–thaw exposure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HE | Hooked-end fiber |

| HPFRCC | High-performance fiber reinforced concrete |

| HRWR | High-range water reducer |

| LOP | Limit of proportionality |

| LVDT | Linear variable differential transformer |

| MOR | Modulus of rupture |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| SHCC | Strain hardening cement composite |

| ST | straight microfiber |

| UHPC | Ultra-high-performance concrete |

References

- Graybeal, B. Design and Construction of Field-Cast UHPC Connections; FHWA-HRT-14-084; Federal Highway Administration: McLean, VA, USA, 2014.

- Graybeal, B.A.; Helou, R. Structural Design with Ultra-High Performance Concrete; FHWA-HRT-23-077; Federal Highway Administration: McLean, VA, USA, 2023.

- ACI Committee 239. ACI 239R-18 Ultra-High-Performance Concrete: An Emerging Technology Report; American Concrete Institution: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Graybeal, B.; Brühwiler, E.; Kim, B.-S.; Toutlemonde, F.; Voo, Y.L.; Zaghi, A. International Perspective on UHPC in Bridge Engineering. J. Bridg. Eng. 2020, 25, 04020094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graybeal, B. Tech Note|Ultra-High Performance Concrete; FHWA-HRT-11-038; Federal Highway Administration: McLean, VA, USA, 2011.

- Yadak, O.; Banik, D.; Floyd, R.W. Flexural Resistance of Ultra-High Performance Concrete Subjected to Freeze-Thaw Cycles. In Proceedings of the Third International Interactive Symposium on Ultra-High Performance Concrete, Wilmington, DE, USA, 4–7 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, R.; Shafei, B. Performance of fiber-reinforced concrete link slabs with embedded steel and GFRP rebars. Eng. Struct. 2021, 229, 111590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, C. Evaluation of Functionality and Service Life of Ultra-High Performance Concrete Link Slab Connections for Bridges. Master’s Thesis, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Graybeal, B.A. Material Property Characterization of Ultra-High Performance Concrete; FHWA, no. FHWA-HRT-06-103; Federal Highway Administration (FHWA): McLean, VA, USA, 2006; p. 186.

- Ma, Z.; Zhao, T.; Yang, J. Fracture Behavior of Concrete Exposed to the Freeze Thaw Environment. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 04017071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Shi, C.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Z. Durability of ultra-high performance concrete—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 255, 119296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z. Damage mechanisms of ultra-high-performance concrete under freeze–thaw cycling in salt solution considering the effect of rehydration. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 198, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaysi, M.; El-Tawil, S.; Liu, Z.; Hansen, W. Effects of silica powder and cement type on durability of ultra high performance concrete (UHPC). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 66, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneau, O.; Lachemi, M.; Dallaire, É.; Dugat, J.; Aïtcin, P.C. Mechanical properties and durability of two industrial reactive powder concretes. ACI Mater. J. 1997, 94, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasnat, A.; Ghafoori, N. Freeze–Thaw Resistance of Nonproprietary Ultrahigh-Performance Concrete. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 2021, 35, 04021008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Weiss, W.J.; Olek, J. Using Acoustic Emission for the Detection of Damage Caused by Tensile Loading and Its Impact on The Freeze-Thaw Resistance of Concrete. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Construction Materials (CONMAT 05), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22–24 August 2005; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Magureanu, C.; Sosa, I.; Negrutiu, C.; Heghes, B. Mechanical Properties and Durability of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete. Mater. J. 2012, 109, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, E.; Shrive, N.G.; Allena, S.; Newtson, C.M. Optimization of mechanical properties and durability of reactive powder concrete. ACI Mater. J. 2007, 104, 547. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, H.-D.; Rokugo, K. Freeze-thaw influence on the flexural properties of ductile fiber-reinforced cementitious composites (DFRCCs) for durable infrastructures. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2012, 78, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-G.; Wang, W.-C.; Wang, Y.-C.; Kan, Y.-C.; Lin, S.-L.; Cheng, L.-C. High temperature and freeze-thaw study of strengthened concrete with ultra-high-performance concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, A.; Hitomi, Y.; Hoshiro, H. PVA-fiber reinforced high performance cement board. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on HPFRCC in Structural Applications, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–26 May 2005; pp. 243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Rokugo, K.; Moriyama, M.; Lim, S.C.; Asano, Y. Tensile performance of pre cracked SHCC after freeze-thaw cycles. In 7th International RILEM Symposium on FRC: Design and Application; RILEM Publications: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 1071–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.-J.; Rokugo, K.; Park, W.-S.; Yun, H.-D. Influence of rapid freeze-thaw cycling on the mechanical properties of sustainable strain-hardening cement composite (2SHCC). Materials 2014, 7, 1422–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.-J.; Zeng, W.-B.; Ye, Y.-Y.; Liao, J.; Zhuge, Y.; Fan, T.-H. Flexural Behavior of FRP Grid Reinforced Ultra-High Performance Concrete Composite Plates with Different Types of Fibers. Eng. Struct. 2022, 272, 115020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.-H.; Zeng, J.-J.; Hu, X.; Chen, J.-D.; Wu, P.-P.; Liu, H.-T.; Zhuge, Y. Flexural Fatigue Behavior of FRP-Reinforced UHPC Tubular Beams. Eng. Struct. 2025, 330, 119848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, R.W.; Volz, J.S.; Zaman, M.; Dyachkova, Y.; Roswurm, S.; Choate, J.; Looney, T.; Campos, R.; Walker, C. Development of Non-Proprietary UHPC Mix; Report No. ABC-UTC-2016-C2-OU01; Accelerated Bridge Construction University Transportation Center, Florida International University: Miami, FL, USA, 2024; 150p. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Shi, C.; He, W.; Wu, L. Effects Of Steel Fiber Content And Shape on Mechanical Properties of Ultra-High Performance Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 103, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Hoang, A.; Fehling, E. Influence of Steel Fiber Content And Aspect Ratio on The Uniaxial Tensile And Compressive Behavior of Ultra High Performance Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 153, 790–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, Z.B.; De la Varga, I.; Graybeal, B.A.; Nakashoji, B.; El-Helou, R. Properties and Behavior of UHPC-Class Materials; Report No. FHWA-HRT-18-036; Federal Highway Administration: McLean, VA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM Standard C666; Standard Test Method for Resistance of Concrete to Rapid Freezing and Thawing. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM Standard C1856; Standard Practice for Fabricating and Testing Specimens of Ultra-High Performance Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Gu, C.; Sun, W.; Guo, L.; Wang, Q. Effect of Curing Conditions on the Durability of Ultra-High Performance Concrete under Flexural Load. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Sci. Ed. 2016, 31, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standard C78; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Third-Point Loading). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM Standard C1609; Standard Test Method for Flexural Performance of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (Using Beam with Third-Point Loading). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Banik, D. Assessment of Ultra-High-Performance-Concrete (UHPC) Properties Using Different Fibers. Master’s Thesis, The University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA, 2022. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11244/335979 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- ASTM Standard C215; Standard Test Method for Fundamental Transverse, Longitudinal, and Torsional Resonant Frequencies of Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Banik, D.; He, R.; Lu, N.; Feng, Y. Mitigation mechanisms of alkali silica reaction through the incorporation of colloidal nanoSiO2 in accelerated mortar bar testing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 422, 135834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type I Cement | Silica Fume | Slag Cement | Masonry Sand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Dolese 1 | Norchem 2 | LafargeHolcim 3 | Metro Materials 4 |

| Reaction Type | Hydraulic | Pozzolanic | Pozzolanic | None |

| Shape of Particle | Angular | Spherical | Amorphous | Angular |

| Specific Gravity | 3.15 | 2.22 | 2.97 | 2.63 |

| D50 (micrometer) | 9.94 | 18.75 | 8.25 | 222.12 |

| Constituent | Mix Proportion |

|---|---|

| Type I Cement | 0.3 |

| Silica Fume | 0.05 |

| Slag Cement | 0.15 |

| Masonry Sand (1:1 agg/cm) | 0.5 |

| w/b | 0.2 |

| Fiber Type | Length (mm) | Diameter (mm) | Aspect Ratio | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Specific Gravity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST | 13 | 0.2 | 63.6 | 2800 | 7.8 |

| HE | 30 | 0.38 | 80 | 3070 | 7.8 |

| Fiber Content | fLOP (MPa) | fMOR (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| ST-2% | 11.90 | 25.48 |

| HE-1% | 7.86 | 14.52 |

| HE-2% | 9.45 | 23.12 |

| HE-4% | 11.80 | 32.43 |

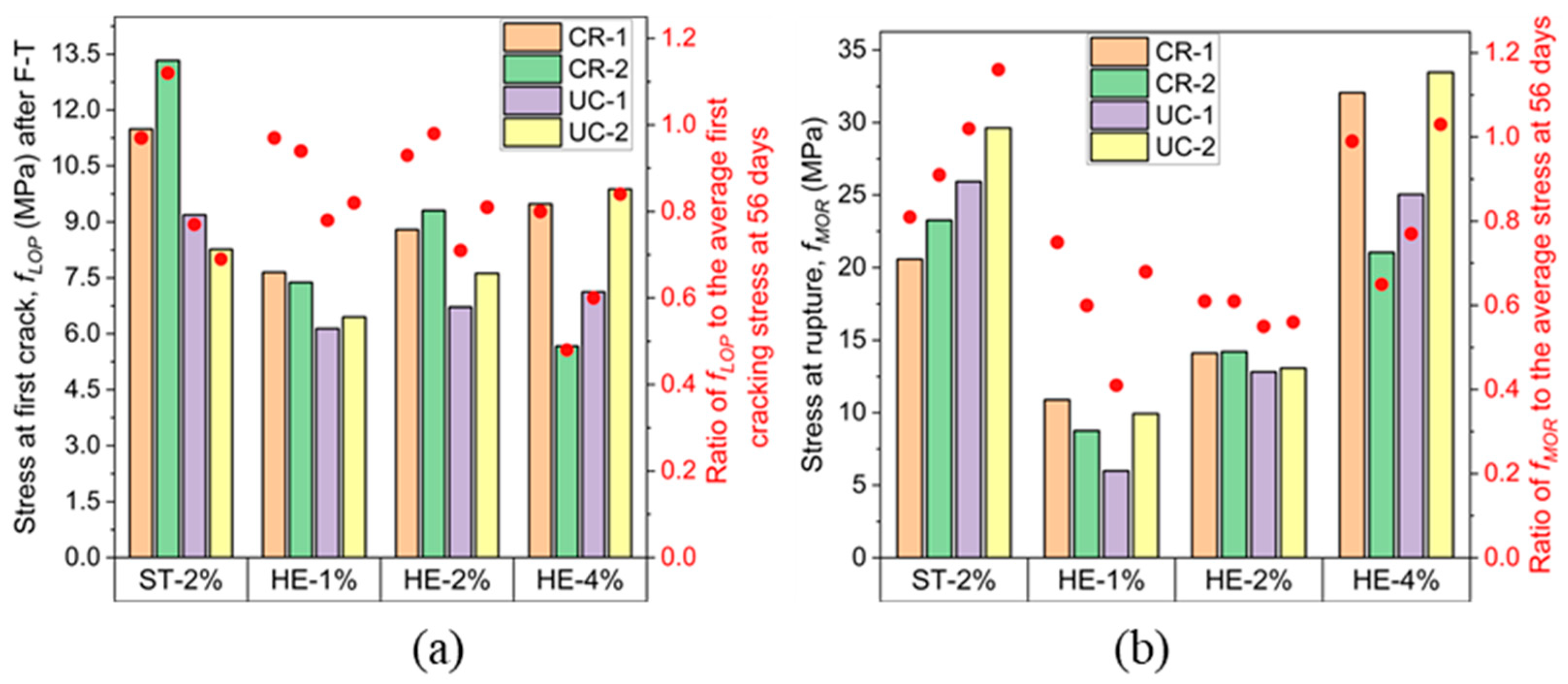

| Fiber Content | Specimen | Stress at First Cracking, fLOP (MPa) | Ratio of fLOP to fLOP at 56 Days | Ultimate Strength, fMOR (MPa) | Deflection at Ultimate Strength, δMOR (mm) | Ratio of fMOR to fMOR at 56 Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST-2% | CR-1 | 11.49 | 0.81 | 20.57 | 1.397 | 0.81 |

| CR-2 | 13.33 | 0.91 | 23.27 | 0.831 | 0.91 | |

| UC-1 | 9.19 | 1.02 | 25.93 | 1.237 | 1.02 | |

| UC-2 | 8.27 | 1.16 | 29.62 | 1.227 | 1.16 | |

| HE-1% | CR-1 | 7.65 | 0.75 | 10.89 | 1.245 | 0.75 |

| CR-2 | 7.38 | 0.60 | 8.76 | 0.381 | 0.60 | |

| UC-1 | 6.134 | 0.41 | 6.00 | 1.168 | 0.41 | |

| UC-2 | 6.45 | 0.68 | 9.93 | 0.711 | 0.68 | |

| HE-2% | CR-1 | 8.79 | 0.61 | 14.10 | 0.762 | 0.61 |

| CR-2 | 9.31 | 0.61 | 14.20 | 0.914 | 0.61 | |

| UC-1 | 6.72 | 0.55 | 12.82 | 1.448 | 0.55 | |

| UC-2 | 7.62 | 0.56 | 13.07 | 1.473 | 0.56 | |

| HE-4% | CR-1 | 9.48 | 0.99 | 32.05 | 1.295 | 0.99 |

| CR-2 | 5.67 | 0.65 | 21.05 | 1.778 | 0.65 | |

| UC-1 | 7.12 | 0.77 | 25.04 | 1.321 | 0.77 | |

| UC-2 | 9.88 | 1.03 | 33.45 | 1.346 | 1.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Banik, D.; Yadak, O.; Floyd, R. Flexural Performance of Pre-Cracked UHPC with Varying Fiber Contents and Fiber Types Exposed to Freeze–Thaw Cycles. J. Compos. Sci. 2026, 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010005

Banik D, Yadak O, Floyd R. Flexural Performance of Pre-Cracked UHPC with Varying Fiber Contents and Fiber Types Exposed to Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Journal of Composites Science. 2026; 10(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanik, Dip, Omar Yadak, and Royce Floyd. 2026. "Flexural Performance of Pre-Cracked UHPC with Varying Fiber Contents and Fiber Types Exposed to Freeze–Thaw Cycles" Journal of Composites Science 10, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010005

APA StyleBanik, D., Yadak, O., & Floyd, R. (2026). Flexural Performance of Pre-Cracked UHPC with Varying Fiber Contents and Fiber Types Exposed to Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Journal of Composites Science, 10(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010005