1. Introduction

Externally bonded CFRP laminates have become a prominent technique for upgrading steel beams, combining high specific stiffness/strength with corrosion resistance and rapid installation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. When applied to the tension flange, CFRP typically enhances flexural stiffness and ultimate capacity while reducing service deflections. These benefits are attractive for bridge and building applications where access windows are short and increased dead load from welded/bolted cover plates is undesirable. However, the extent to which these gains are realized is governed by the adhesive layer and its interface with steel, where interfacial shear and peel stresses localize, especially near laminate terminations, often precipitating premature debonding if the bond is not properly detailed [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Field deployments on steel girders further highlight surface preparation quality, bond durability, and moisture/temperature management as decisive factors for long-term performance [

12,

13].

Laboratory programs consistently report two governing failure modes in CFRP-strengthened steel beams: adhesive debonding (end- or intermediate-debonding initiated by interfacial stress peaks) and laminate rupture once bond transfer is sufficient for the CFRP to reach its tensile limit. The boundary between these modes is controlled by a small set of design-sensitive variables: bonded length, termination detailing (tapers/filets, splice plates, wraps), laminate thickness/modulus, adhesive properties and thickness, and steel member geometry. Several studies report diminishing returns with increasing bonded length: once interfacial stresses have decayed from the free end, typically over a fraction of the span in simply supported beams, the flexural capacity plateaus, and additional bonded length provides only small gains unless fatigue or serviceability requirements govern [

9,

10,

11,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Thicker or higher-modulus laminates raise flexural rigidity and peak moment but can elevate peel stresses near plate ends; unless termination geometry and adhesive toughness are upgraded, thicker laminates may shift the governing limit state back toward debonding [

18,

19]. Conversely, appropriately tough and sufficiently thick adhesives promote favorable stress redistribution, delaying damage initiation and stabilizing post-yield response; very stiff or very thin layers can aggravate peel and precipitate brittle separation [

8,

16,

19]. End anchorages (e.g., CFRP/GFRP wraps, mechanical plates) and reverse tapers reduce local stress concentrations and shift the failure mode toward rupture while improving ductility [

10,

19].

From a mechanics standpoint, the steel–adhesive–CFRP assembly acts as a hybrid flexural member with strong shear-lag and peel effects at the interface. Analytical models reduce the problem to coupled differential equations for axial and interfacial fields, leading to exponential decay of shear/peel away from the laminate ends. This behavior motivates the concept of an “effective” bond length, beyond which additional length is underutilized. The addition of tapers or spew filets smooths stiffness jumps and reduces local singularities, which is consistent with observed delays in debonding initiation [

9,

10,

11]. When the steel section yields, plastic redistribution increases interfacial demands under the loading points and near terminations, which explains the intermediate debonding observed in some tests even when end detailing is improved.

High-fidelity finite element (FE) formulations using cohesive zone traction–separation laws with damage initiation and softening reproduced load–deflection response, interfacial stress transfer, and progressive debonding with good fidelity against benchmark experiments [

8,

18]. Compared with 2D simplifications, 3D models better capture lateral–torsional coupling, out-of-plane flange warping, contact at supports/loading blocks, and localized stress concentrations near terminations or geometric changes [

18]. Reliable prediction depends on cohesive parameters, peak tractions, fracture energies (mode I, mode II, and mixed-mode), and initial stiffness. These are calibrated from dedicated tests or inverse identification to capture failure-mode transitions and identify plateau regimes in bonded length and laminate thickness [

14,

20,

21,

22]. Validated FE datasets have also been used to train regression-based ML models that quantify parameter influence (e.g., number of plies, adhesive thickness, reinforcement spacing) and enable rapid screening of strengthening layouts without exhaustive testing [

23]. For cyclic loading, CZM extensions incorporating unloading–reloading paths and cyclic damage evolution have been shown to capture subcritical crack growth and bond degradation more realistically than monotonic laws [

22].

Beyond static capacity, the durability of the bond under moisture, temperature cycles, and hygrothermal environments is a key determinant of service life. Epoxy systems with appropriate glass transition temperature and moisture resistance, coupled with galvanic isolation strategies between carbon fibers and steel, are standard field practices [

12,

13]. Installation procedures, grit blasting to a specified surface profile, solvent cleaning, controlled adhesive mixing/dispensing, bond-line thickness control, and cure management govern initial bond quality. Quality assurance measures such as tap-testing, infrared thermography, or pull-off adhesion tests provide early detection of voids or weak adhesion. These practical aspects are frequently decisive: laboratory gains are only realized in the field when process control ensures consistent bond performance. From a constructability perspective, partial-length laminates with optimized terminations can reduce material and installation time while achieving most of the attainable capacity, provided that termination detailing addresses local stresses and anticipated fatigue demands [

10,

15,

16,

17,

19].

Despite the maturity of CFRP retrofitting of steel beams and the wide availability of experimental data and 3D finite-element models with cohesive-zone formulations [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

22], several practitioner-oriented gaps remain. Existing studies have clarified the main strengthening mechanisms and typical failure modes, adhesive debonding versus CFRP rupture, and have highlighted the influence of bonded length, laminate thickness, termination detailing, and adhesive properties [

9,

10,

11,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, most investigations vary only one or two parameters within narrow ranges and report case-specific load–deflection curves. This makes it difficult to build a consolidated mapping that shows how bond-centric variables (cohesive strength, bonded length) and member-level geometry (beam depth, flange and web thickness) jointly govern both ultimate capacity and the transition between debonding and rupture. Without an explicit view of these interactions, design choices often favor material additions, extra laminate length or thickness and heavier sections that deliver diminishing returns because interface demands precipitate end or intermediate debonding before the laminate capacity is mobilized [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. At the same time, there is limited translation from detailed cohesive FE analyses into design-grade guidance: the literature offers few compact ranges or simple tools that practicing engineers can apply directly at pre-design stage, such as effective bond-length thresholds for typical spans, practical targets for cohesive strength/toughness of commonly used adhesives, or cost–capacity charts linking capacity gains to material and strengthening cost [

9,

10,

11,

15,

16,

17,

19,

22]. There is a particular need for quantified effect sizes, clear identification of plateau regimes, and explicit failure-mode boundaries that can be used directly in design checks.

This present work addresses these gaps by using a validated three-dimensional FE model with an explicit cohesive-zone representation of the adhesive. A structured parametric study is then performed under monotonic four-point bending. The aim is not to propose a new constitutive law or optimization algorithm. Instead, a realistic interface model is used to quantify how a small set of geometric and cohesive parameters influences the global response and the governing failure mode. The numerical results are finally condensed into simple expressions and diagrams for direct use in preliminary design.

Within this framework, the paper makes three main contributions. First, it develops and calibrates a 3D ANSYS model of CFRP-strengthened steel I-beams that matches benchmark tests in terms of peak load, mid-span deflection, and the transition from end/intermediate debonding to CFRP rupture. This provides a reproducible numerical benchmark. Second, it conducts a one-factor-at-a-time parametric study in which beam depth, flange and web thickness, CFRP bonded length, laminate thickness, and cohesive strength are varied systematically. This reveals effective bond-length and cohesive-strength thresholds beyond which laminate thickening becomes efficient, and it identifies parameter regions where the governing failure mode switches from debonding to rupture. Third, it derives a simple surrogate expression for peak load and constructs failure-mode and cost–capacity diagrams that summarize the influence of the main parameters and highlight the trade-offs between capacity increase and material cost. Together, these contributions support pre-design of CFRP-strengthened steel beams and provide a basis for future extensions to cyclic and environmental loading.

2. Numerical Modeling

Samples tested by Lenwari et al. [

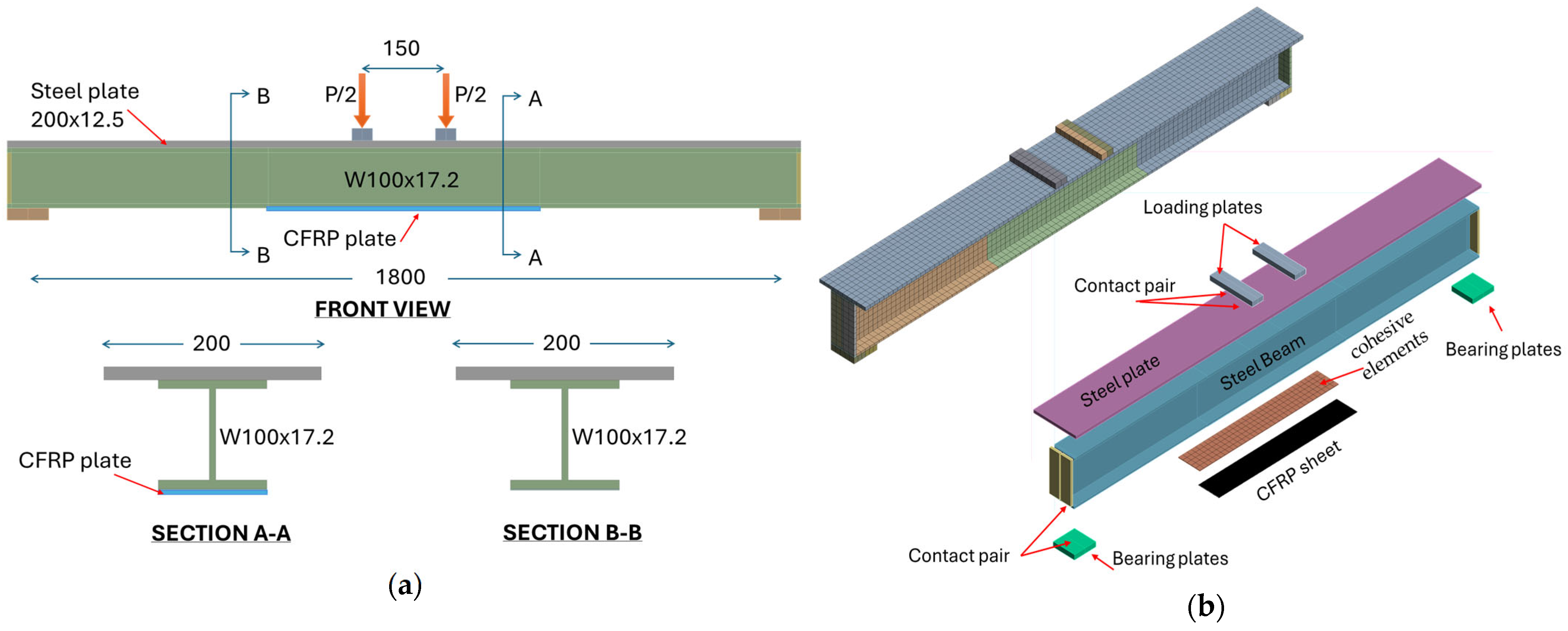

9] were used to validate the numerical mode. A three-dimensional model of a W100×17.2 steel I-beam strengthened with partial-length CFRP strips was developed in ANSYS 25.0 [

24,

25] to replicate the four-point bending configuration used in the benchmark program. A 200 × 12.2 mm cover plate was welded to the compression flange to prevent the lateral torsional buckling. The total beam length is 1900 mm with a clear span of 1800 mm between a pin and a roller; 100 × 100 × 20 mm bearing plates are included at the supports to distribute reactions and avoid artificial stress concentrations. Loading is applied through two 200 × 50 × 20 mm plates placed symmetrically at ±75 mm from mid-span, generating a constant-moment region consistent with the tests. The strengthened configuration follows the experimental arrangement with two Sika

® CarboDur H514 plates bonded to the tension flange in selected lengths (650, 750 and 1200 mm). These features are modeled explicitly so that contact pressures, local rotations and interface demand develop realistically under bending (

Figure 1a shows the test layout, beam cross-section, and CFRP placement).

Steel is assigned an elastic–plastic bilinear law (Elastic Modulus € = 200 GPa, Poisson’s Ratio (ν) = 0.30, Yield Strength (F

y) = 300 MPa) to capture yielding while preserving elastic response in non-critical load-distribution plates. The CFRP plates are modeled as linear elastic up to rupture with properties of the H514 laminate (E ≈ 300 GPa, ν = 0.30). Rupture is assumed when the longitudinal stress in the laminate reaches the reported fiber breaking stress of the H514 strip, 1400 MPa, as measured in Lenwari et al. [

9].

All solid parts (beam, loading and bearing plates) are meshed with hexahedral SOLID185 elements. Additional frictionless contact pairs (CONTA174/TARGE170) are defined only between the beam and the bearing plates and between the beam and the loading plates (

Figure 1b) to prevent interpenetration and to transmit compression once local debonding develops. Nonlinear static solution is performed under displacement control applied at the loading plates to a target actuator displacement of −15 mm. Large-deflection kinematics, automatic time stepping and bisection are enabled to maintain convergence through softening and to trace post-peak response. The mesh layout, interface discretization, and boundary/contact conditions are illustrated in

Figure 1, with a cohesive layer through-thickness placement.

The adhesive layer between the steel bottom flange and the CFRP plate is represented by zero-thickness cohesive interface elements available in ANSYS (INTER205). The interface behavior is governed by a standard bilinear mixed-mode traction–separation law, as implemented in the ANSYS cohesive zone material model and widely used in the literature on delamination and interface failure [

24,

26,

27]. The law relates the nominal tractions

to the corresponding separations

where the subscripts

and

denote the normal (opening) and tangential (slip) directions, respectively. Compression across the interface does not induce damage, so only the positive part of the normal separation

is considered in the normal traction. In the undamaged regime the cohesive response is linear elastic, with penalty stiffnesses

and

in the normal and tangential directions:

Damage initiation is assumed to occur when the nominal stresses reach the cohesive strengths of the adhesive. Once damage initiates, the interface stiffness degrades according to a scalar damage variable

, where

corresponds to the undamaged state and

to complete decohesion. The nominal tractions in the damaged regime become:

Damage evolution is driven by an effective separation

that combines the normal and tangential components:

The damage variable grows linearly with

from its onset value

to the failure value

:

The onset separation

is related to the cohesive strengths and penalty stiffnesses via Equation (1). The failure separation

is chosen such that the area under the traction–separation curve matches the target fracture energies

and

in pure mode I and II. For the adopted bilinear law:

where

and

are the normal and tangential separations at complete decohesion in pure mode I and II, respectively. In mixed-mode loading, damage evolution is governed by the same linear law in terms of the effective separation

, so that the relative contributions of mode I and mode II are naturally controlled by the evolving normal and tangential separations at the interface. This cohesive formulation allows the model to capture both end-initiated debonding and rupture-governed cases by appropriate combinations of cohesive strength and fracture energy.

In the present model the baseline interface is parameterized by equal strengths, and equal characteristic separations in normal and shear, δn = δs = 1 × 10−5 mm, in line with the bulk tensile and shear strengths reported in the US datasheet of the Sikadur-30 epoxy adhesive, and subsequently calibrated to reproduce the experimental peak load and failure mode of the reference beam.

To establish the credibility and accuracy of the developed finite-element analysis model, we validated it against experimental results reported in the literature [

9], using the same performance indicators as the tests: ultimate (peak) load, the corresponding mid-span deflection at that load, and the observed failure mode. The intent is not to condense findings but to reproduce, one-to-one, the measured structural response of FRP-strengthened steel beams and to show that the numerical model replicates that behavior with the precision required for subsequent parametric investigations.

In the experimental study of Lenwari et al. [

9], the flexural behavior of steel beams strengthened with CFRP plates was investigated under four-point bending. Seven W100×17.2 rolled steel beams with a clear span of 1.80 m were tested (

Figure 1a). Strengthening used partial-length CFRP plates of 0.50 m, 0.65 m, and 1.20 m, approximately 5/18, 1/3, and 2/3 of the span, bonded to the tension flange. Specimens were designated by plate length in centimeters (e.g., B65-1 denotes a 650 mm plate). To emulate repair scenarios, some beams were pre-yielded before strengthening and marked with the suffix “Y”: B65Y-1 and B120Y-1 were reused from B65-1 and B120-1, respectively, reaching preloads of 129% and 172% of the calculated yield load (83.2 kN) prior to CFRP application. Each beam received two Sika

® CarboDur H514 plates, 50 mm wide and 1.4 mm thick, bonded with a 1 mm SikaDur-30 epoxy layer. Reported CFRP properties were an elastic modulus of 300 GPa, fiber breaking stress of 1400 MPa, and tensile strength of 1800 MPa. To prevent compressive flange yielding, steel plates were welded to the compression flanges. Instrumentation comprised twenty strain gauges and three LVDTs per beam to record CFRP tensile strain, stress distribution, and deflection. The four-point load was applied via a spreader beam with two rollers spaced 150 mm apart, and all channels were recorded automatically.

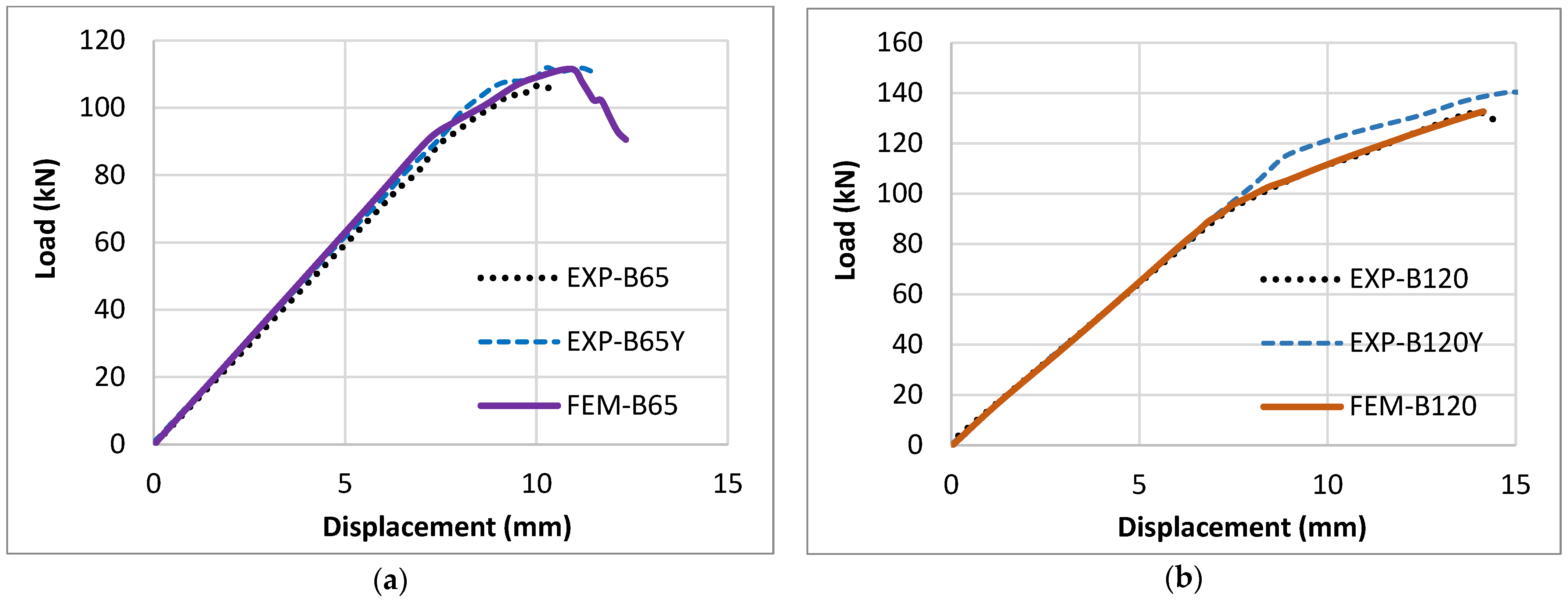

Numerical validation follows the same configurations. For the 650 mm bonded length (BS-650), the numerical load–displacement curve overlays the experimental response through the initial linear regime and up to peak (

Figure 2a). The experimental peak is 111.49 kN at 11.30 mm; the FEA prediction is 110.83 kN at 10.83 mm. The differences are 0.59% in peak load and 1.22% in deflection, confirming that the elastic stiffness and peak response of the steel–adhesive–CFRP assembly are captured. For the 1200 mm bonded length (BS-1200),

Figure 2b demonstrates good agreement in global trend and peak: the experiment recorded 139.65 kN at 14.08 mm, compared with 131.92 kN at 14.15 mm from the simulation, i.e., 5.14% lower peak load and 0.48% difference in peak deflection. The responses across the two lengths are consistent with the expected progression of the governing mechanism: earlier end-initiated debonding for shorter plates and delayed debonding with greater laminate utilization for the longer plate.

3. Parametric Study Setup

The experimentally validated numerical model was used to perform parametric study. This practice is a common practice and has been used in several previous studies [

28,

29]. The parametric study uses the same four-point bending configuration, materials, and numerical settings to ensure that observed differences stem only from the parameter under investigation. The specimen is a W100×17.2 steel I-beam of total length 1900 mm with a clear span of 1800 mm, supported by a pin at one end and a roller at the other through 100 × 100 × 20 mm bearing plates. Loading is applied via two 200 × 50 × 20 mm steel plates positioned symmetrically at ±75 mm from mid-span. Two parallel CFRP strips (Sika CarboDur H514, 50 mm × 1.4 mm) are bonded to the tension flange with a nominal 1 mm SikaDur-30 epoxy layer. The finite-element model employs SOLID185 for the steel beam and accessory plates, INTER205 for the adhesive interface governed by the same bilinear mixed-mode traction–separation law described in

Section 2, and CONTA174/TARGE170 to manage contact and separation once damage initiates. A uniform 20 mm brick mesh is retained throughout. This baseline configuration, denoted BS650 when the bonded length is 650 mm, uses a cohesive normal strength of 24.8 MPa and serves as the control against which all single-factor variations are compared.

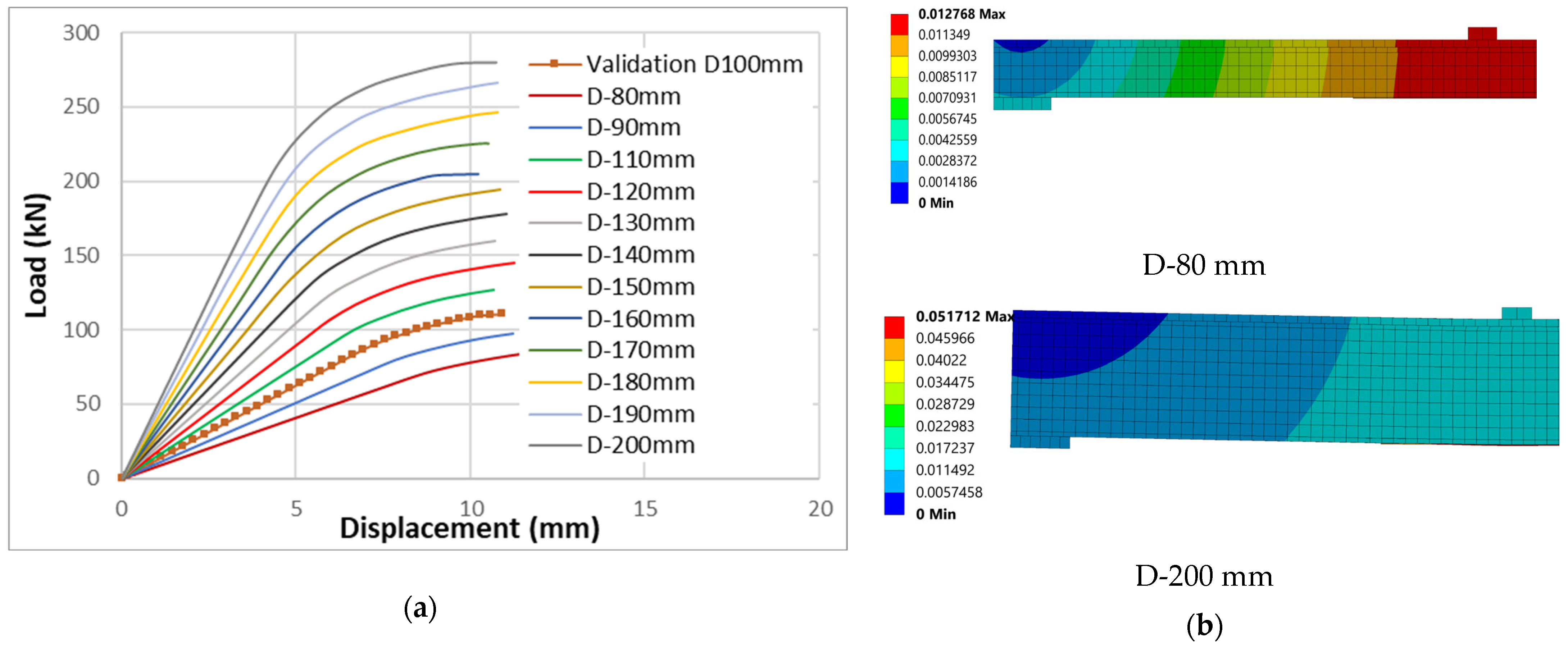

With the control established, each design variable is varied one at a time while all other inputs remain fixed at baseline values so that individual sensitivities can be isolated cleanly. Beam depth is swept from 80 mm to 200 mm (notation D-XXX, e.g., D-100), with beam width held at 100 mm, bonded length at 650 mm, laminate thickness at 1.4 mm, and cohesive strength at 24.8 MPa. CFRP bonded length is varied from 350 mm to 1200 mm (notation CL-XXX), covering a “short” subset (350–650 mm) and a “long” subset (700–1200 mm). Cohesive capacity is examined by stepping the interface peak traction from 5 to 35 MPa at explicit levels of 5, 8, 10, 13, 15, 17, 20, 23, 24.8, 27, 30, 33, and 35 MPa (notation CZM-XX). CFRP thickness spans 0.6–3.0 mm (notation TC-XX). Finally, the steel section is adjusted through bottom-flange thickness in the range 3–15 mm (notation TF-XX) and web thickness in the same 3–15 mm range (notation TW-XX).

To keep the study transparent and reproducible, the full one-factor matrix is assembled in a single design table where for each block, the varied level is listed alongside the fixed baseline settings for geometry, materials, cohesive law, mesh, and boundary conditions. The BS-650 control accompanies every series so that envelopes and peak metrics can be compared on a like-for-like basis. For clarity in later discussion, the bonded-length block is ordered from the shortest to the longest plate, the cohesive-strength block is ordered from the lowest to the highest traction level, and the geometry blocks progress from the smallest to the largest thickness or depth. This consolidated matrix is presented as

Table 1.

Each simulation is conducted under monotonic displacement control applied at the loading plates, with large-deflection kinematics and identical convergence settings to those used for the baseline. For every case, four primary outputs are extracted: the global load–displacement envelope, the peak load , the corresponding mid-span deflection , and the governing failure mode. The latter is identified from the evolution of the interface damage variables along the bonded length and from the utilization of the CFRP laminate at peak, distinguishing adhesive debonding from laminate rupture where applicable. No numerical parameters (elements, mesh size, contact settings, sub-stepping) are altered between cases, isolating the influence of the single varied parameter on the computed response.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Effect of CFRP Bonded Length

Extending the bonded length is analyzed for its impact on the global response, the laminate’s utilization, and the governing failure mode in four-point bending. The motivation is straightforward: if the transfer length is short, interfacial shear/peel near the plate ends precipitates early debonding; if it is sufficiently long, the laminate can be mobilized toward rupture.

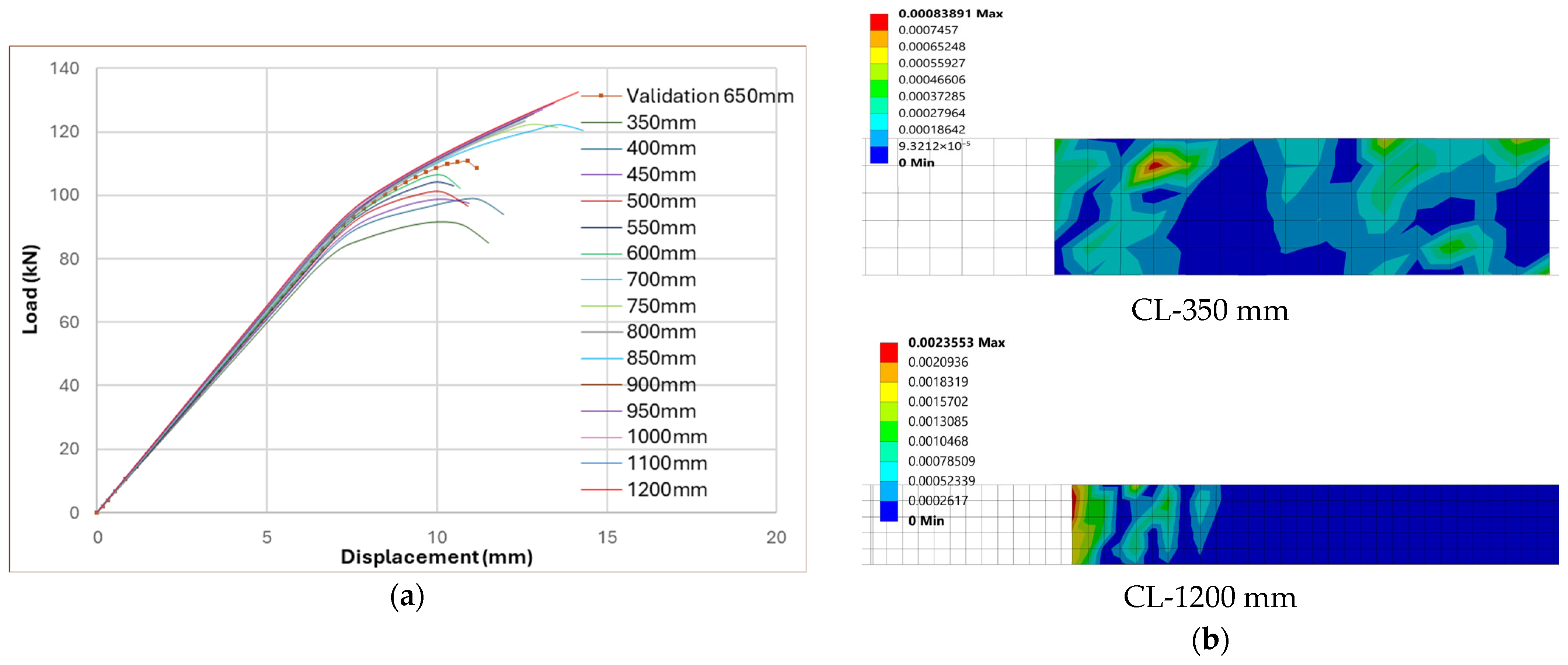

Figure 3a overlays the load-deflection response for

= 350, 650, 700, 800, 900, 1000, 1100, 1200 mm.

Figure 3b reports the bond-sliding (relative shear displacement) distribution at peak load along the bonded length for two bounding cases of bonded length,

= 350 mm (short bond) and

= 1200 mm (long bond). For completeness,

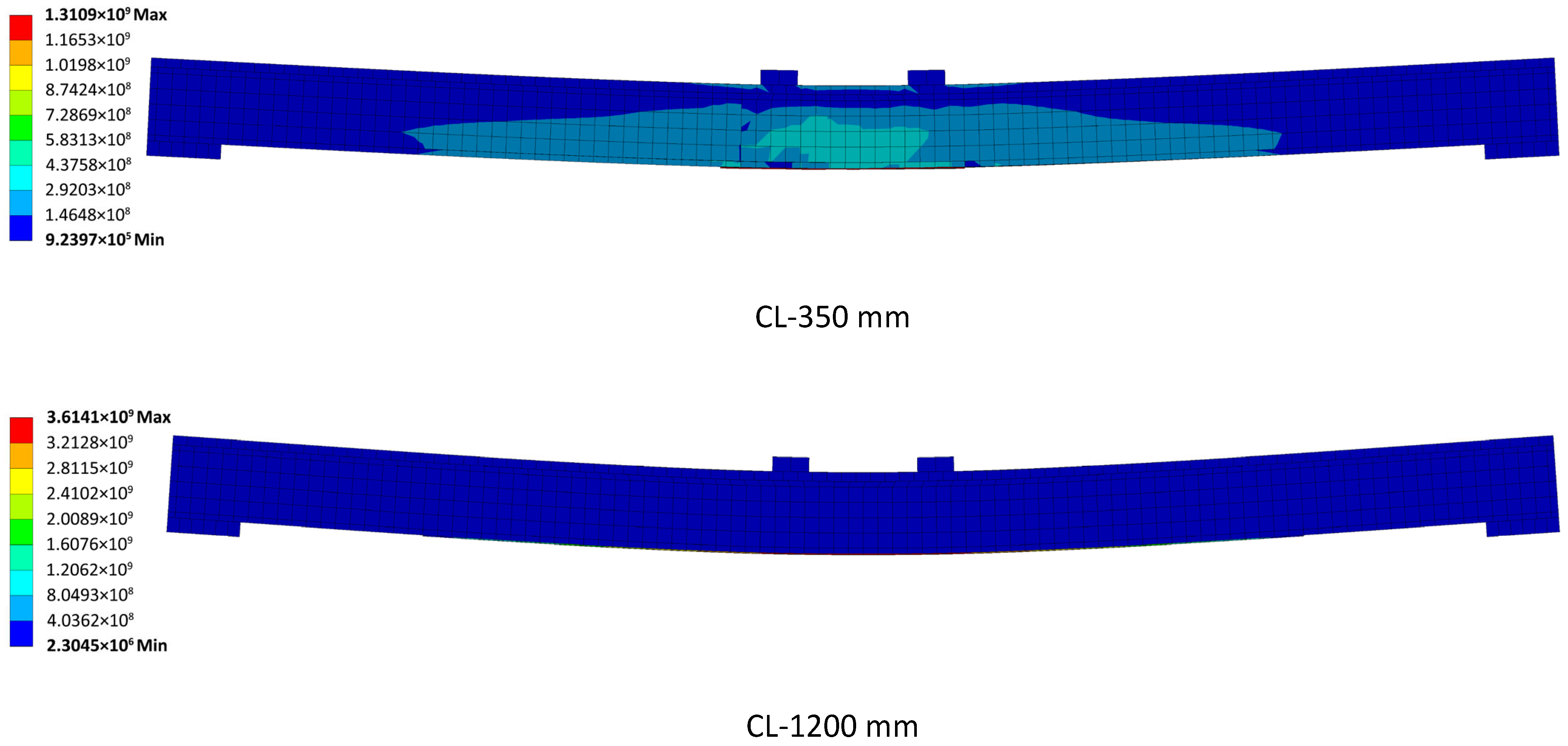

Figure 4 contrasts the corresponding von-Mises stress fields (short vs. long

) at peak, highlighting how hotspot locations evolve with

.

In the short-bond regime (350–650 mm), the response improves relative to the unstrengthened beam, but failure is governed by end-initiated debonding. Representative peaks are CL-350 = 91.56 kN at 11.53 mm and CL-650 = 110.83 kN at 10.89 mm, with damage maps showing separation concentrated in the first few tens of millimeters from each termination. Entering the transition regime (700 mm), the FE envelope rises sharply and the failure mode flips. Between CL-650 (110.83 kN) and CL-700 (122.11 kN) the increase is around 10%, and the governing mode changes to CFRP rupture; at the same time the peak deflection increases, reflecting later damage initiation and greater laminate participation. In the long-bond regime (800–1200 mm), additional length yields diminishing gains: the envelopes for CL-800…CL-1100 cluster tightly (123.5–129.3 kN) and continue to fail by rupture, while the longest plate reaches CL-1200 = 132.47 kN at 14.15 mm. The damage field along the bond line grows progressively quieter and more uniform as the bond length is increased, confirming that once the transfer length is exceeded, capacity is no longer capped by the interface.

Relative to

= 350 mm, the

= 1200 mm case exhibits a marked capacity increase and a change in the governing failure from end-initiated debonding to CFRP rupture. The bond-sliding map in

Figure 3b confirms strong localization within the first few tens of millimeters from each termination for

= 350 mm, whereas

= 1200 mm shows attenuated end gradients and a flatter sliding profile, evidence of more uniform stress transfer into the constant-moment region. Consistently,

Figure 4 shows hotspot stresses concentrated near the interface ends for the short bond, but migrating to the laminate gauge section for the long bond, indicating fuller laminate utilization.

4.2. Effect of Cohesive Strength

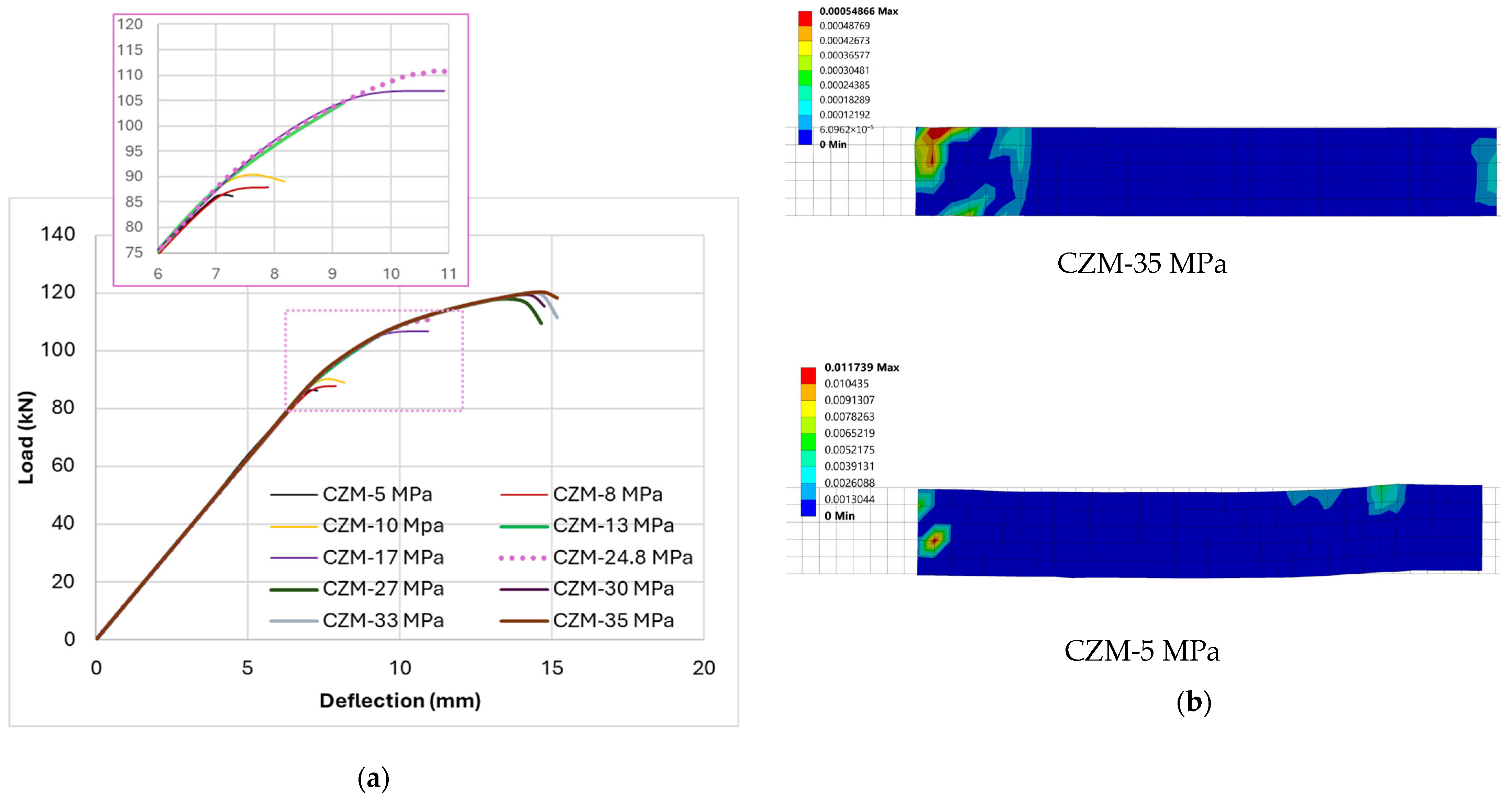

By varying the cohesive normal traction with geometry and laminate properties held constant, we quantify when the adhesive interface controls the response and pinpoint the traction level at which failure shifts from debonding to rupture.

Figure 5 shows (a) the load–displacement curves for different cohesive strengths (

= 5, 8, 10, 13, 15, 17, 20, 23, 24.8, 27, 30, 33, 35 MPa) and (b) the bond-sliding distribution at peak load along the bonded length.

The results at low cohesive strengths (5–10 MPa) exhibit early deviation from linearity and end-initiated debonding as the governing limit state, with limited peak loads and small peak deflections; a representative case is CZM-5 = 86.21 kN at 7.28 mm. As the cohesive strength is raised through the intermediate range (13–24.8 MPa), both the initial stiffness and peak load increase, and the onset of interface damage moves closer to the peak, yet debonding still governs; the baseline case at 24.8 MPa reaches 110.83 kN at 10.89 mm with damage concentrated in the first elements from each laminate termination. Entering the threshold band (around 27 MPa) produces the most significant discrete improvement: CZM-27 attains 118.11 kN at 13.36 mm, and the failure mode switches to CFRP rupture. This step represents the largest single gain relative to the baseline (6.5% in peak load) and is accompanied by a noticeable increase in peak deflection, indicating later damage initiation and greater laminate utilization. Beyond the threshold, further increases to 30–35 MPa yield only marginal gains in capacity (119–120 kN), and the interface damage at peak is minimal along most of the bond-line, confirming that the interface is no longer the primary limiter once the cohesive strength exceeds the transition.

Raising cohesive strength delays interface damage, increases peak capacity, and, beyond a narrow pivot, changes the governing failure from end-initiated debonding to CFRP rupture. In

Figure 5b, lower cohesive strength (5 MPa) displays steep sliding gradients confined to the first tens of millimeters from each termination, whereas higher strength (35 MPa) exhibits flatter profiles with attenuated end localization, indicating more uniform stress transfer.

4.3. Effect of CFRP Thickness

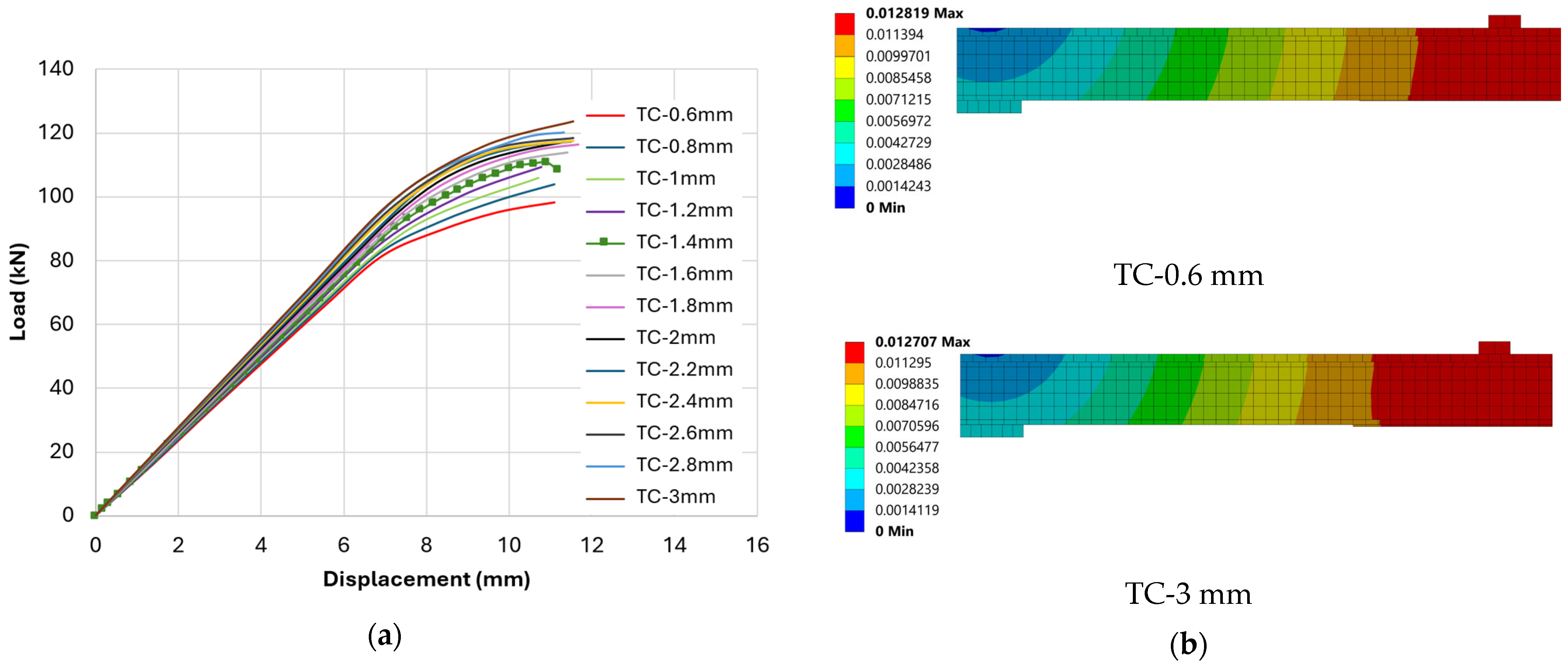

Holding bonded length and interface properties at their baseline values, we evaluate the influence of CFRP laminate thickness on capacity, peak deformation, and failure mode to determine the mobilization range of added material and the conditions under which the interface governs.

Figure 6 compares (a) FE load–displacement envelopes different CFRP thicknesses (0.6–3.0 mm) and (b) the effect of CFRP thickness on deformation and stress at peak load.

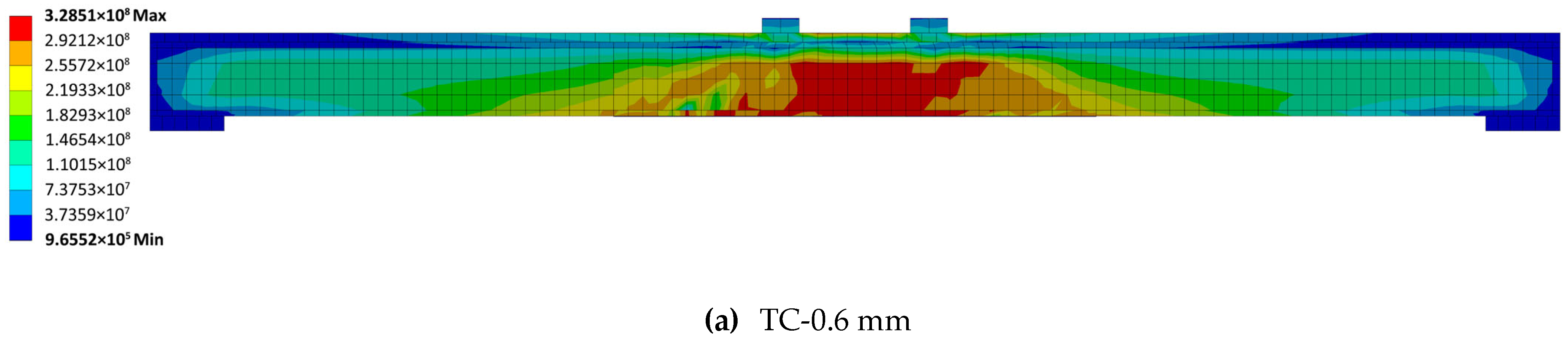

Figure 7 shows the corresponding von Mises stress fields.

The FE results separate into two clear bands defined by the failure mechanism. For thinner laminates (

≤ 1.2 mm), capacity increases with thickness and CFRP rupture governs. Representative peaks are TC-0.6 = 98.22 kN and TC-1.2 = 109.43 kN, with envelopes in

Figure 6 showing smooth rises and sharper post-peak drops characteristic of rupture. In this band, interface damage at peak is limited, indicating that the bond is sufficient to mobilize the laminate up to its tensile limit. Crossing to thicker laminates (

≥ 1.4 mm) under the same interface settings, the system reverts to adhesive debonding as the governing mode.

The baseline thickness TC-1.4 reaches 110.83 kN, and increasing to TC-3.0 lifts the peak to 123.67 kN; however, the corresponding damage maps show intensified end-peel at the laminate terminations, and the envelopes exhibit more gradual softening after peak, both signatures of debonding. Under the present bonded length and cohesive settings, raising beyond 1.4 mm still provides capacity gains (e.g., TC-3.0 = 123.67 kN), but these gains are accompanied by stronger end-damage and do not reflect full utilization of the added laminate.

With TC-0.6, the deflection field exhibits larger mid-span displacement and steeper curvature in the constant-moment region, and the von Mises hotspots concentrate near the bond ends and bottom flange, consistent with interface-controlled behavior. Increasing to TC-3 reduces the global deflection and flattens the deformation gradient, while the von-Mises distribution shifts away from the ends toward the laminate gauge section/constant-moment region, indicating more effective use of the laminate.

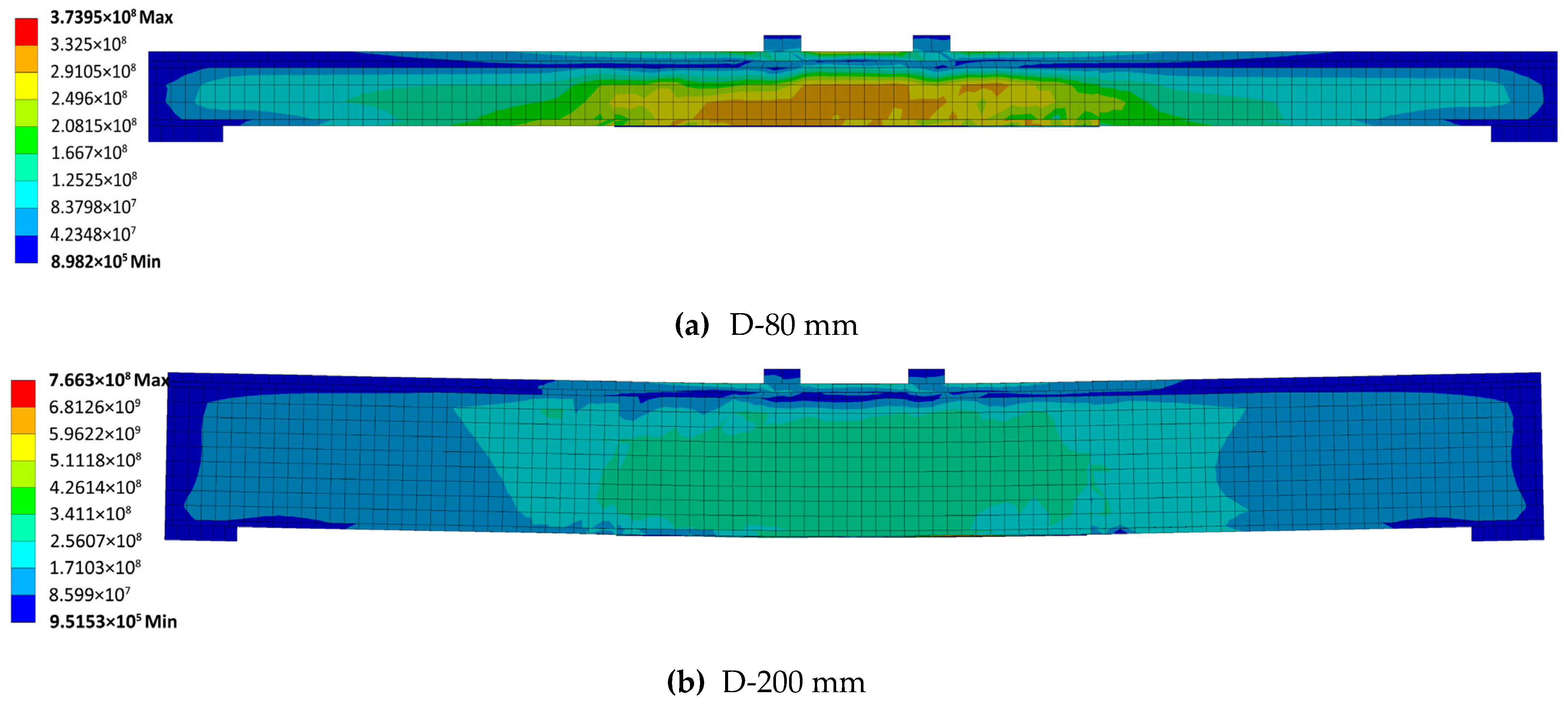

4.4. Effect of Steel Beam Depth

With bonded length and interface properties held constant, we assess how greater section depth amplifies global capacity and modifies deformation at peak within the same cohesive strength.

Figure 8 compares load–displacement curves at beam depth D = 80, 100, 150, 200 mm; since all other inputs are held constant (

= 650 mm;

= 1.4 mm;

= 24.8 MPa), the response shifts arise solely from the change in depth.

Figure 8b reports the peak-load deflection contours for two bounding depths, D-80 and D-200, while

Figure 9 shows the corresponding von-Mises stress fields for the same cases.

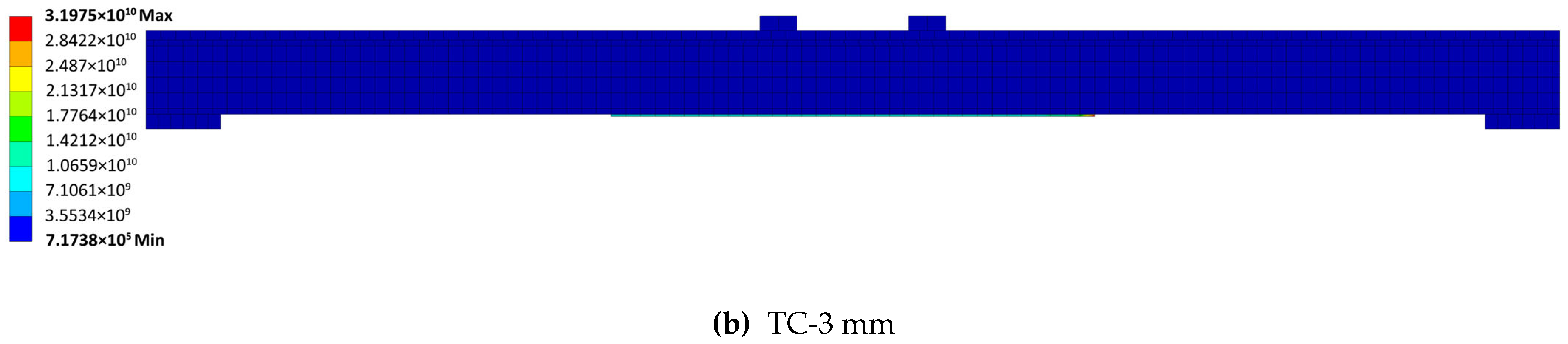

The FE results show a strong, monotonic increase in peak load with depth, accompanied by higher initial stiffness and modest shifts in deflection at peak. Relative to the shallowest section (D-80), the deepest section (D-200) achieves about a 218% increase in capacity. Despite these substantial improvements in the global envelope, the governing failure mode remains adhesive debonding across the set, and the peak-state interface damage in

Figure 8b confirms the same end-initiated separation pattern observed in the baseline. This persistence of debonding indicates that, under the baseline bond conditions, increased section depth alone cannot shift the limit state; the interface continues to cap the utilization of the strengthened section.

The depth series clarifies that enlarging the steel section is an effective way to raise stiffness and peak load, but the full benefit will not be realized unless the bonded length and/or cohesive capacity are first increased to delay or suppress end debonding. Increasing depth from D-80 to D-200 noticeably reduces mid-span deflection and flattens curvature in the constant-moment region (

Figure 8b), consistent with the higher flexural stiffness. In

Figure 9, D-80 concentrates von Mises hotspots near the bond ends and bottom flange, reflecting larger rotations and end-peel demand; for D-200, hotspots de-localize and shift toward the laminate gauge/constant-moment region, indicating better laminate utilization and reduced end damage propensity.

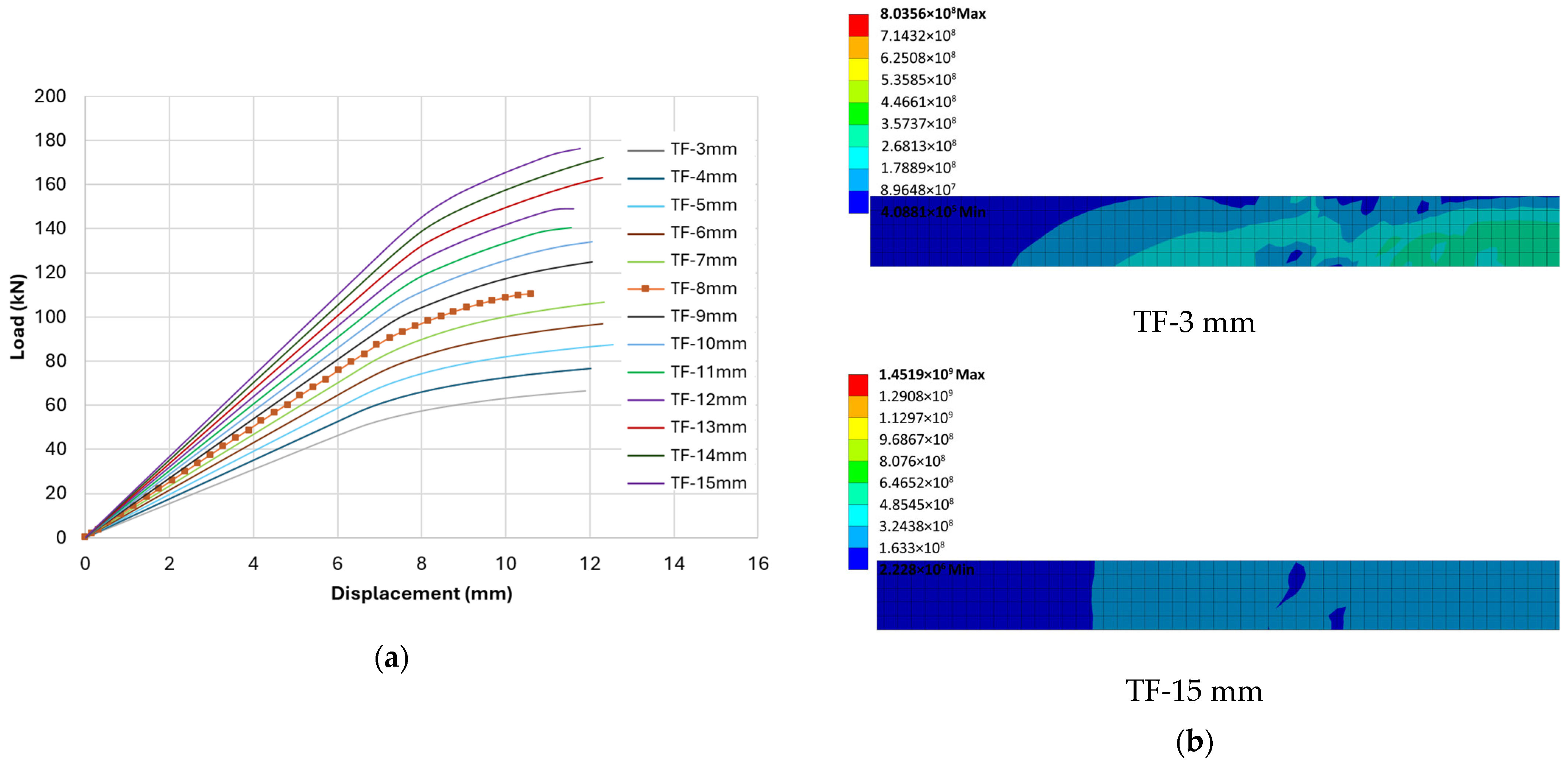

4.5. Effect of Bottom Flange Thickness

To distinguish true capacity gains from proportional scaling, we vary the tension-flange thickness under the CFRP and hold

= 650 mm,

= 1.4 mm, and

= 24.8 MPa. FE load–displacement curves for

= 3–15 mm are overlaid in

Figure 10a and the von Mises stress fields at peak load for two bounding bottom-flange thicknesses are shown in

Figure 10b. The FE results show that capacity increases markedly with flange thickening, but the failure mechanism remains adhesive debonding once local flange instability is suppressed. The thinnest flange (TF-3) reaches 66.46 kN and exhibits local buckling followed by debonding, a two-stage response evident in the softening branch of the envelope and in the concentrated damage at the plate ends. Increasing to TF-5 and beyond removes the local instability from the response: representative cases include TF-8 = 110.37 kN and TF-15 = 176.30 kN, both failing by end-initiated debonding with peak-state damage confined to the first elements at each termination.

Increasing the bottom-flange thickness from 3 mm to 15 mm reduces stress concentration near the bond ends, consistent with lower local rotations and peel demand; the peak-stress region becomes broader and less intense, indicating more effective diffusion of stresses into the flange. Flange thickening is effective at raising global capacity and eliminating local tensile-flange instability, yet it does not alter the ultimate limit state under baseline bond conditions: the interface continues to cap utilization, with debonding initiating at the CFRP terminations.

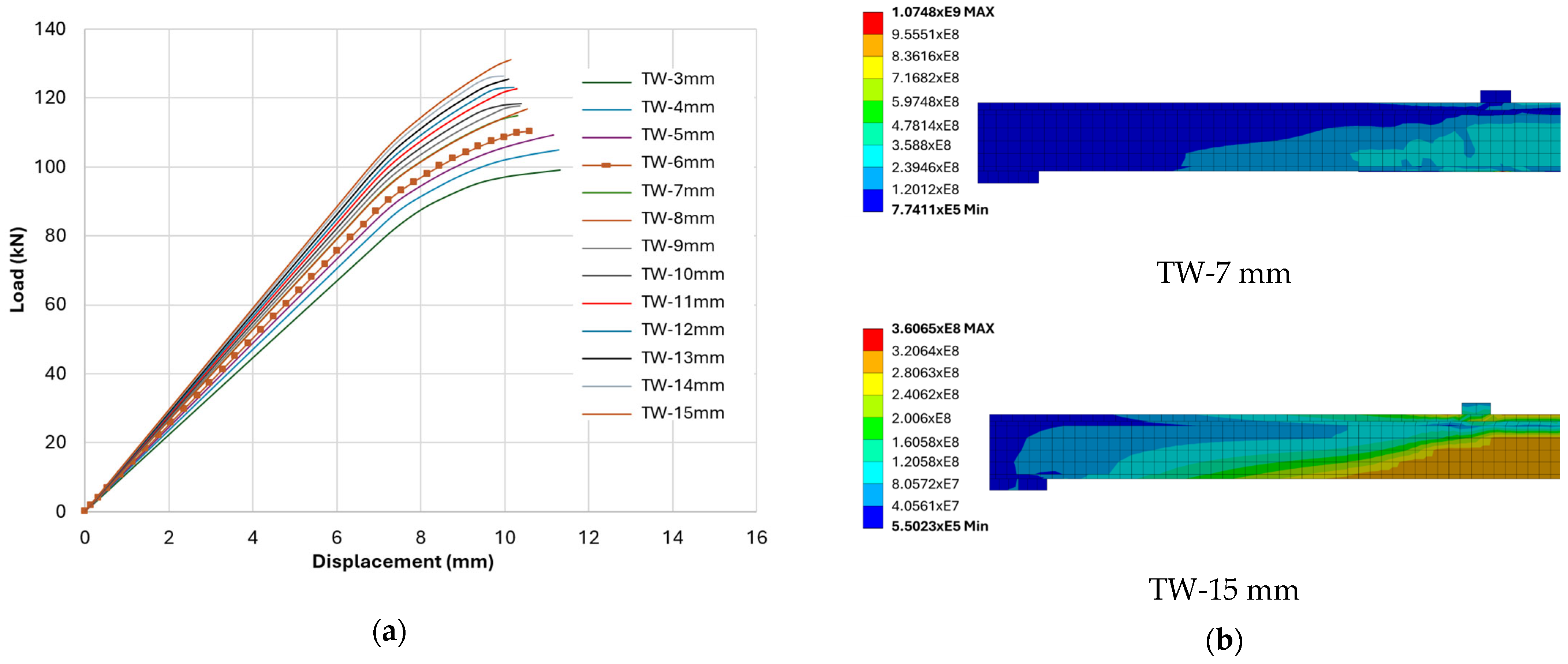

4.6. Effect of Web Thickness

Holding

= 650 mm,

= 1.4 mm, and

= 24.8 MPa, we vary web thickness to test whether gains stem from enhanced shear rigidity/load transfer or merely scale the response without shifting the limit state. FE results for

= 3–15 mm are overlaid in

Figure 11a.

Figure 11b presents the von Mises stress fields at peak load for two bounding web thicknesses.

The FE results show a steady but moderate increase in peak load and a small reduction in deflection at peak as the web is thickened across the studied range, with adhesive debonding remaining the governing failure mode in all cases. Representative points along the series are TW-3 = 99.00 kN at 11.31 mm, TW-8 = 116.93 kN at 10.53 mm, and TW-15 = 132.36 kN at 10.47 mm. The envelope shapes in

Figure 11a retain the same elastic slope followed by a gradual softening branch, while the peak-state damage fields in

Figure 11b consistently display end-initiated separation confined to the first elements at each laminate termination. The modest shift in peak deflection with increasing web thickness is consistent with a stiffer shear path and slightly improved load sharing into the tension flange, but the interface limit asserts itself at peak. Web thickening is an effective secondary measure for improving global stiffness and peak load, yet under baseline bond conditions, it does not alter the ultimate limit state. Increasing the web thickness from 7 mm to 15 mm reduces shear-related distortion and lowers stress concentration near the web–flange junction and bonded region.

4.7. Design-Proximate Sensitivity

This subsection quantifies which parameters are most decisive in practice by ranking small, design-realistic changes using the same finite-element results reported in

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2,

Section 4.3,

Section 4.4,

Section 4.5 and

Section 4.6. Sensitivity is defined as the percentage change in peak load relative to the reference of the comparison,

, with the governing failure mode recorded for each move. The intent is to provide a compact, data-driven ordering of levers that designers can act on without altering the modeling assumptions or the experimental validation basis. The ranked sensitivities are shown in

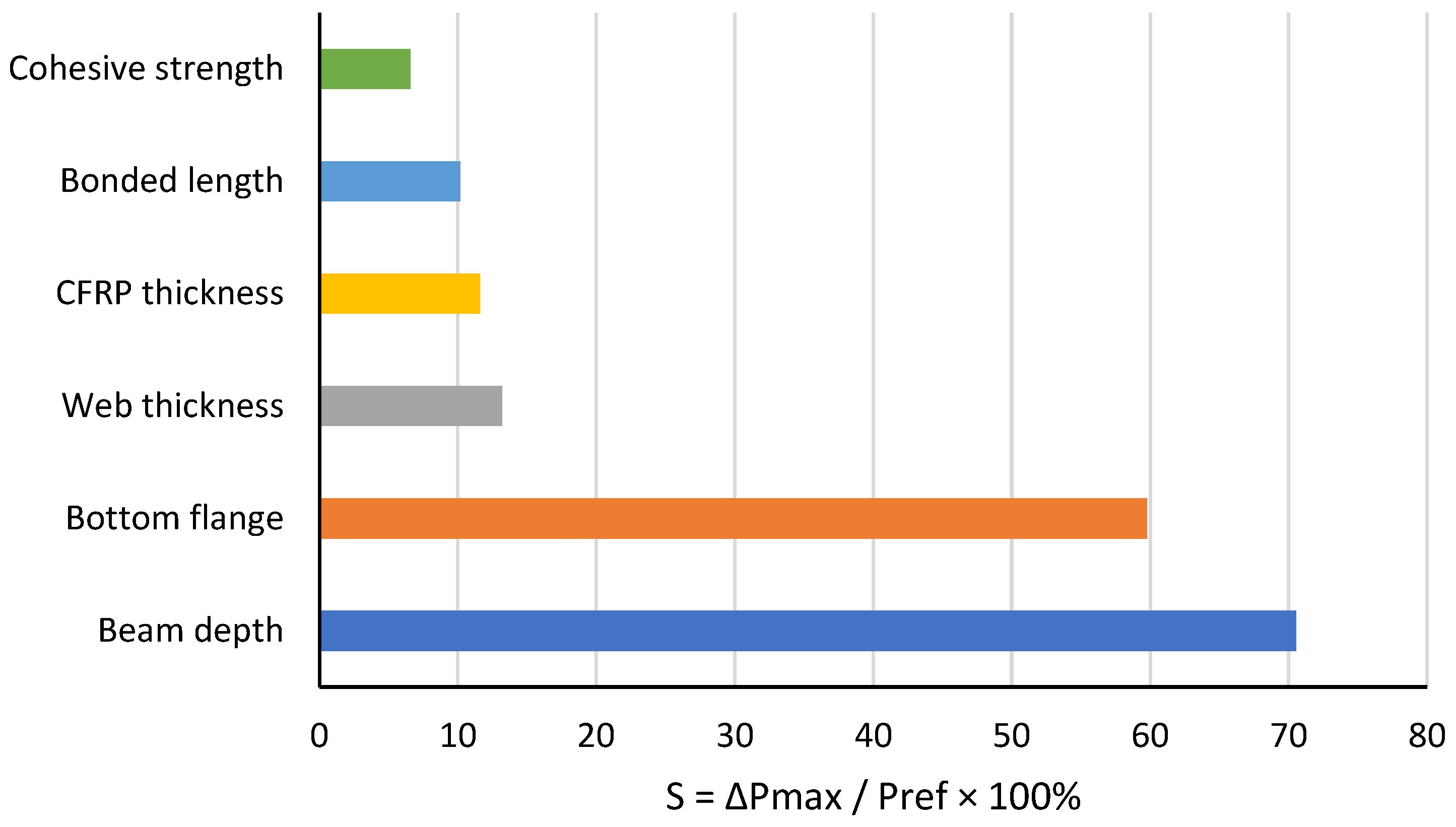

Figure 12, which overlays a tornado plot of the near baseline moves and annotates any change in failure mechanism.

Two bond-centric adjustments produce meaningful gains with a concurrent mode shift: increasing bonded length across the effective-length crossover raises capacity from 110.83 kN to 122.11 kN (+10.18%) and switches the limit state from debonding to CFRP rupture; increasing cohesive strength just above the threshold lifts capacity from 110.83 kN to 118.11 kN (+6.57%) and likewise triggers rupture. Three geometry moves register larger absolute sensitivity but remain debonding-governed under baseline bond conditions. Stepping beam depth increases

from 110.83 kN to 189.00 kN (+70.53%), thickening the bottom flange raises the capacity from 110.37 kN to 176.30 kN (+59.74%), and thickening the web moves from 116.93 kN to 132.36 kN (+13.20%). Finally, increasing CFRP thickness under baseline bond yields +11.59% (from 110.83 kN to 123.67 kN), but the failure mode stays debonding. The FE envelopes and the peak-state damage maps show intensified end-peel as thickness grows, indicating that the extra laminate is not fully mobilized without a concurrent bond upgrade; cross-reference with

Section 4.2 shows that raising

to ~27 MPa restores rupture-governed behavior.

4.8. Towards Pre-Design Use of the FE Results

The full simulation dataset was used to fit a linear regression model for the peak load as a function of the main geometric and bond parameters. For each case, the finite-element analysis provides the peak load together with the values of beam depth D, bonded length

, cohesive normal strength

, CFRP thickness

, bottom-flange thickness

, and web thickness

. A least-squares fit was then carried out with these six variables as input features and peak load as the quantity of interest, leading to the following surrogate relation:

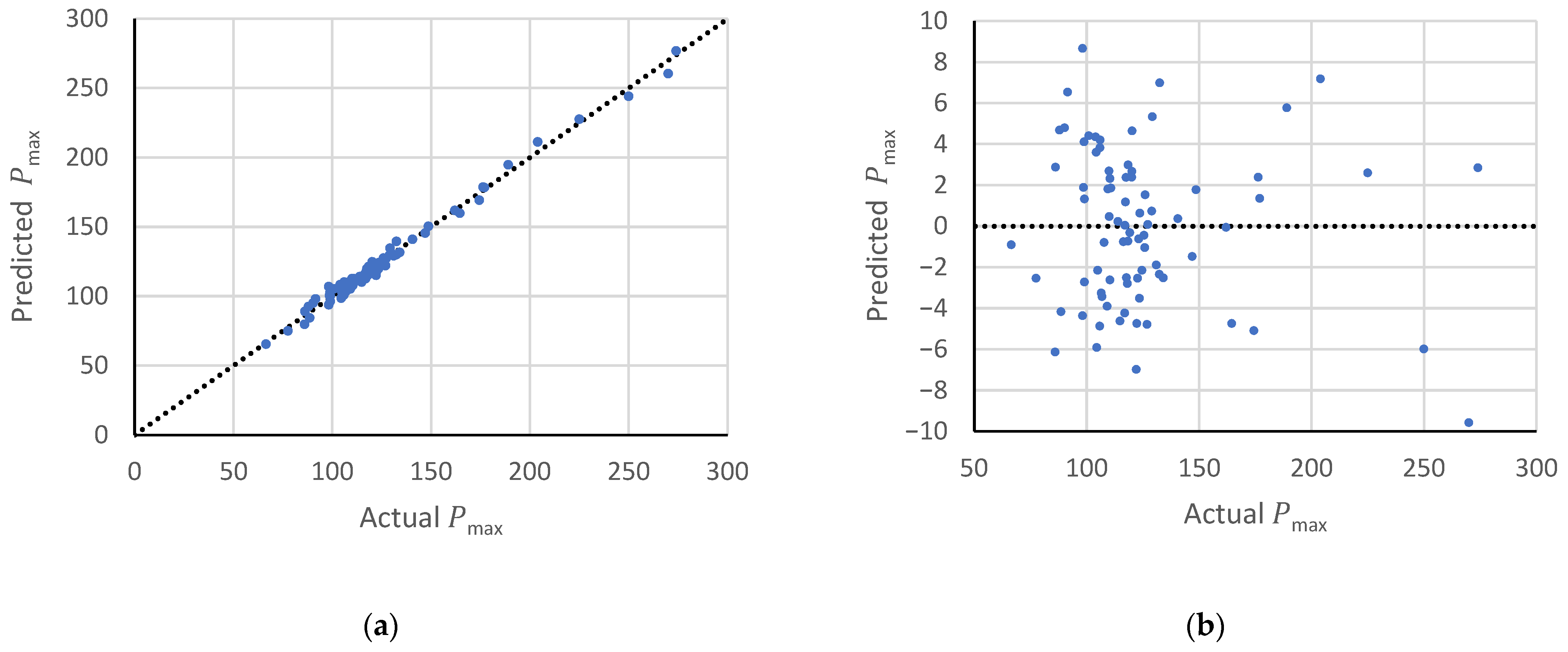

Table 2 summarizes the numerical values of the regression coefficients

, together with the global error measures, coefficient of determination

, root-mean-square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE). Moreover,

Figure 13 illustrates the fit quality, the surrogate predictions have been compared to the finite-element peak loads, and the residuals as a function of the peak load. Each coefficient represents the local change in

associated with a unit change in the corresponding variable:

reflects the influence of extending the bonded length,

quantifies the benefit of increasing cohesive normal strength, and

capture the effect of adding CFRP thickness or steel material to the flange and web.

In practice, these relations are evaluated at baseline configuration defined by

and corresponding peak load

. When all variables are kept at their baseline values except the one under study, the expressions reduce to one-dimensional forms. The simplified form of bonded length reads:

While the cohesive strength as a function of the peak load is given by

For pre-design purposes, the first relation yields the bonded length needed to reach a target capacity when the adhesive and steel section are specified, and the second yields the adhesive strength needed when the geometry and bonded length are prescribed.

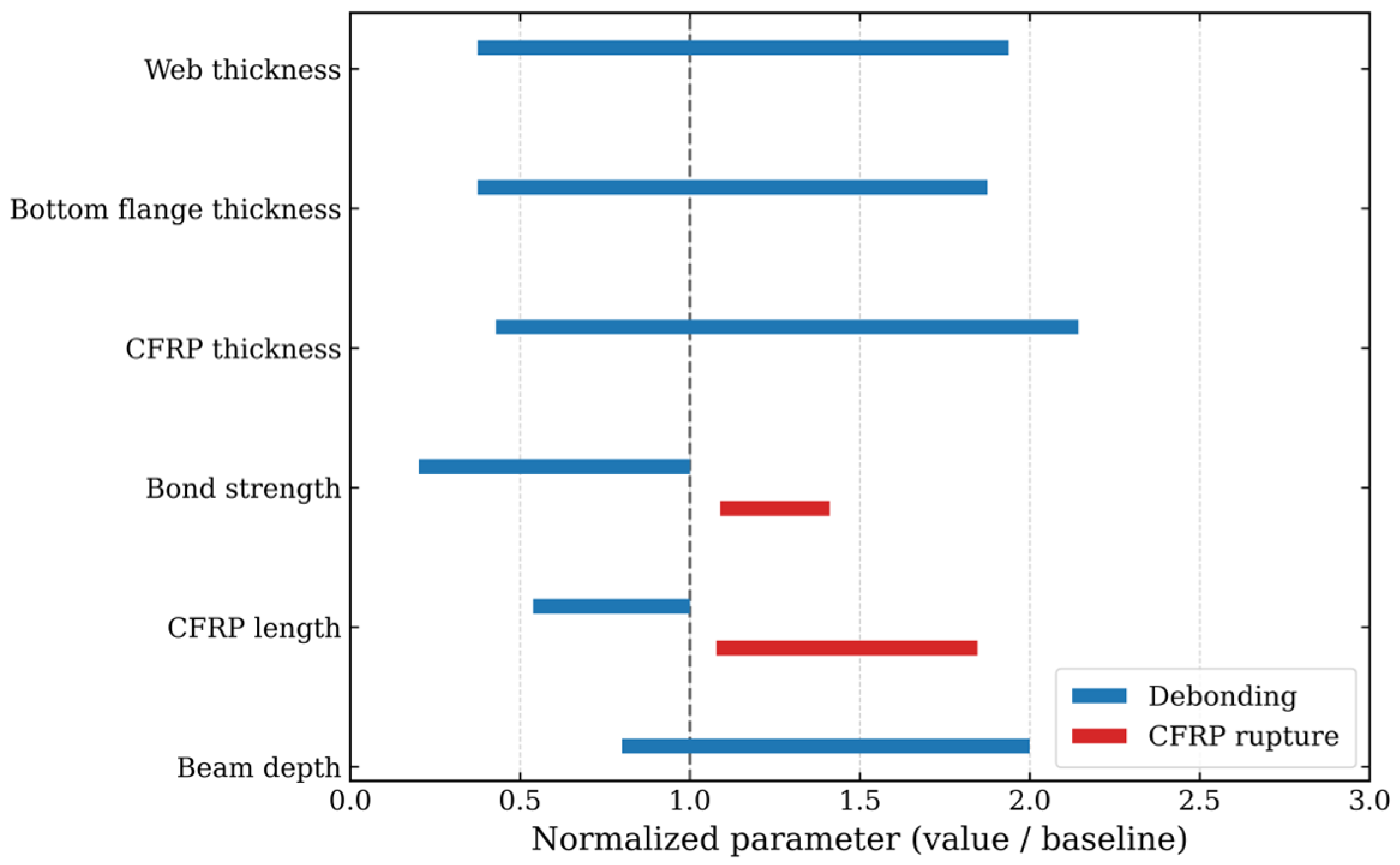

To relate the magnitude of the predicted capacity to the governing failure mode, the finite-element results were post-processed using three indicators: bond sliding along the adhesive, mid-span deflection, and von Mises stress fields. Each simulation was then labeled as either debonding-governed or CFRP-rupture-governed. The corresponding normalized domains are plotted in

Figure 14. Within the ranges investigated, only the CFRP length and bond strength consistently trigger a change in mechanism. The series in which only the cohesive normal strength is varied provides a practical design threshold for the present configuration. For cohesive strengths below approximately 25 MPa, the response remains debonding-governed. Once

exceeds a narrow interval around 27 MPa, the dominant failure mode changes from interface debonding to CFRP rupture, and the marginal benefit of additional laminate becomes significantly larger.

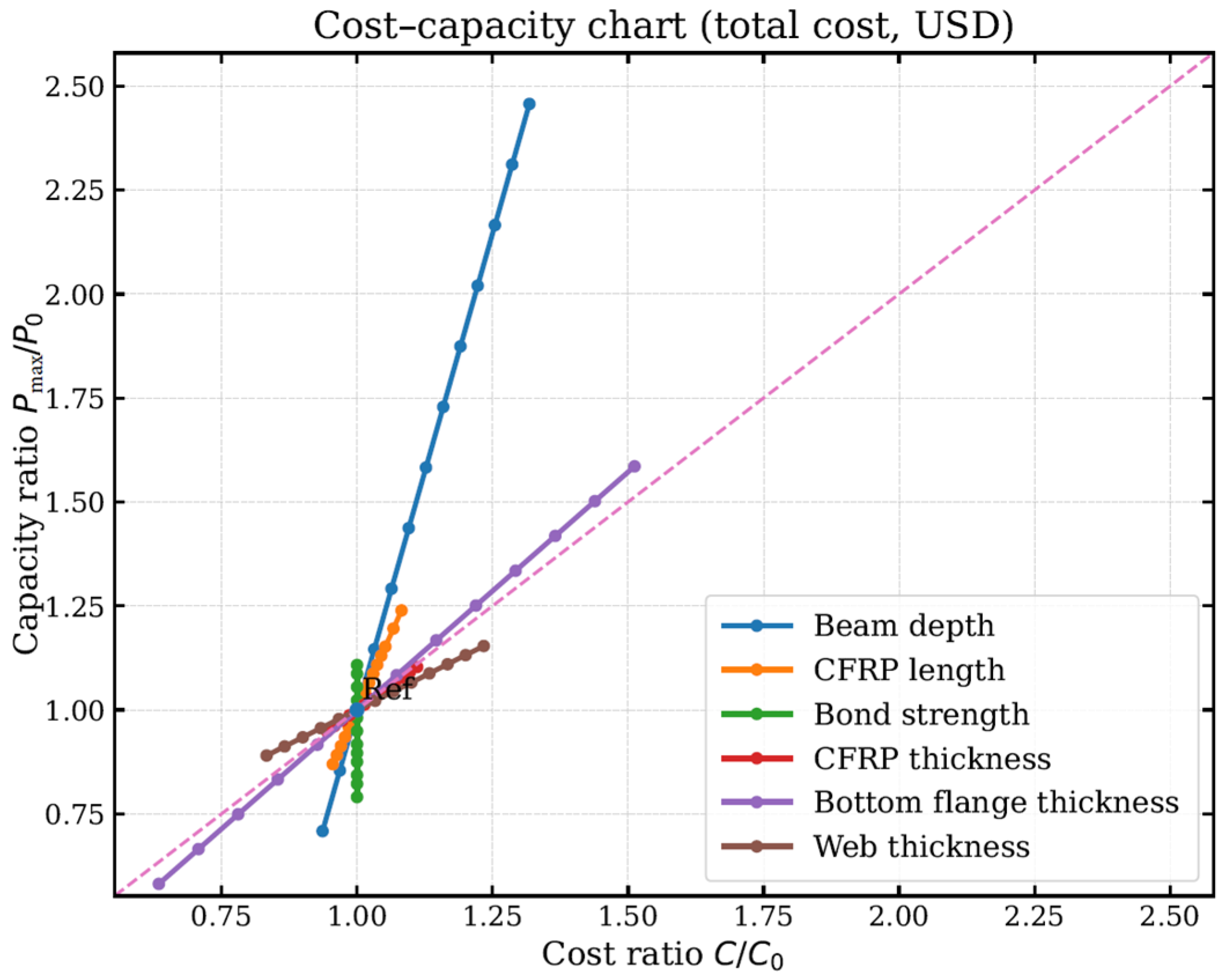

The cost of each configuration was estimated from the material mass and unit price. For the steel beam, the cost was obtained from the section area per meter, and for the CFRP, it was computed from the bonded laminate volume and its unit price. Both cost and peak load were normalized by the baseline values, giving and . Plotting these two quantities defines a cost–capacity chart in which the diagonal through (1,1) marks equal percentage changes in cost and capacity; points above this line are more efficient than the baseline, whereas points below it are less efficient.

In the series where only the CFRP bonded length varies, increasing length raises both cost and capacity. At short and moderate lengths, the points lie above the parity line, showing that added laminate is used efficiently.

Figure 15 shows that the cost increases up to 1.1 while the capacity reaches 1.25 for the longest bonded length. Varying CFRP thickness leads to a much steeper cost increase; when bond strength is insufficient, the extra material contributes only partially to the global response. Changes in cohesive normal strength mainly move the points upward at nearly constant cost, provided that process-related penalties are small. Increasing the steel beam depth generally lies above the parity line and is the most effective steel-side adjustment. Increasing flange thickness follows a path closer to the parity line and provides more modest but steady gains, whereas changes in web thickness typically remain near parity and are better suited to incremental stiffening than to major capacity increases.

5. Conclusions

A three-dimensional finite-element model with an explicit cohesive-zone interface was developed to quantify the flexural response of CFRP-strengthened steel I-beams under monotonic four-point bending. The model reproduced benchmark tests within 1–5% of measured peak load and corresponding mid-span deflection, and captured both end/intermediate debonding and CFRP rupture, indicating that the adopted cohesive parameters are adequate for simulating initiation and propagation of interface damage and the transition to laminate failure.

The parametric study shows that some factors matter much more than others. Bond-related parameters govern the limit state until a traction threshold is exceeded. For the present configuration, cohesive normal strengths below around 25 MPa lead to debonding-governed behavior, whereas values in a narrow band around 27 MPa switch the governing mode to CFRP rupture. Bonded length has an effective range: increasing CL from the short-bond regime into the 650–700 mm interval produces a marked capacity increase and a change in failure mode; further extension beyond this range yields diminishing returns, with only modest additional gains in peak load. Laminate thickening always increases capacity, but under baseline bond conditions, the benefit is limited by stronger end debonding as thickness grows. Once cohesive strength is raised above the threshold, the marginal gain from additional CFRP thickness becomes larger because rupture rather than debonding controls the response.

Changes in steel geometry provide substantial absolute gains but do not alter the ultimate limit state under baseline bond conditions. Increasing beam depth and bottom-flange thickness significantly raises stiffness and Pmax and can eliminate local tensile-flange instability; however, failure remains dominated by end-initiated debonding, and the interface still caps utilization of the strengthened section. Web thickening produces more modest improvements and primarily refines shear stiffness and load sharing. Overall, the results indicate that the bond must be improved before geometric and laminate changes can be fully effective in increasing capacity and altering the failure mode.

The full simulation dataset was condensed into a linear surrogate model for peak load as a function of beam depth, bonded length, cohesive normal strength, CFRP thickness, and flange and web thickness. The regression shows good agreement with the FE results and can be rearranged to give simple one-dimensional relations for the required bonded length or cohesive strength at a target capacity, evaluated about the calibrated baseline. Normalized cost–capacity plots, combining material masses with representative unit prices, indicate that extending bonded length within the effective-range window is initially efficient but quickly approaches parity once the effective bond is exceeded; increasing laminate thickness leads to a much steeper cost increase and is only efficient when bond performance is sufficient; raising cohesive strength mainly shifts designs upward at nearly constant cost, and depth changes are generally more effective than flange or web modifications on the steel side.

Recommendations for Future Work

Extend the validated 3D FE framework with cycle-dependent cohesive degradation (unloading–reloading paths, stiffness/strength decay, mixed-mode fatigue damage) and validate against four-point bending fatigue tests to quantify life, growth rates, and debonding thresholds.

Incorporate temperature–humidity–aging dependencies for the adhesive and CFRP (rate effects, moisture-softening, Tg proximity) and calibrate with targeted durability tests to assess capacity retention and mode stability under service environments.

Systematically compare plain, tapered, reverse-tapered, and hybrid mechanical anchorages within the same FE setup, supported by companion tests, to map peak interfacial stresses, delay of end-debonding, and material efficiency for achieving rupture-governed behavior.

Integrate multi-factor sensitivity and machine-learning-based surrogate models to capture coupled effects and optimize design parameters systematically.