Conceptions and Feasibility Study of Fiber Orientation in the Melt as Part of a Completely Circular Recycling Concept for Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Research Aim

1.2. State of the Art

1.2.1. Effect of Fiber Length and Alignment

1.2.2. Mathematically Description of Fiber Orientation

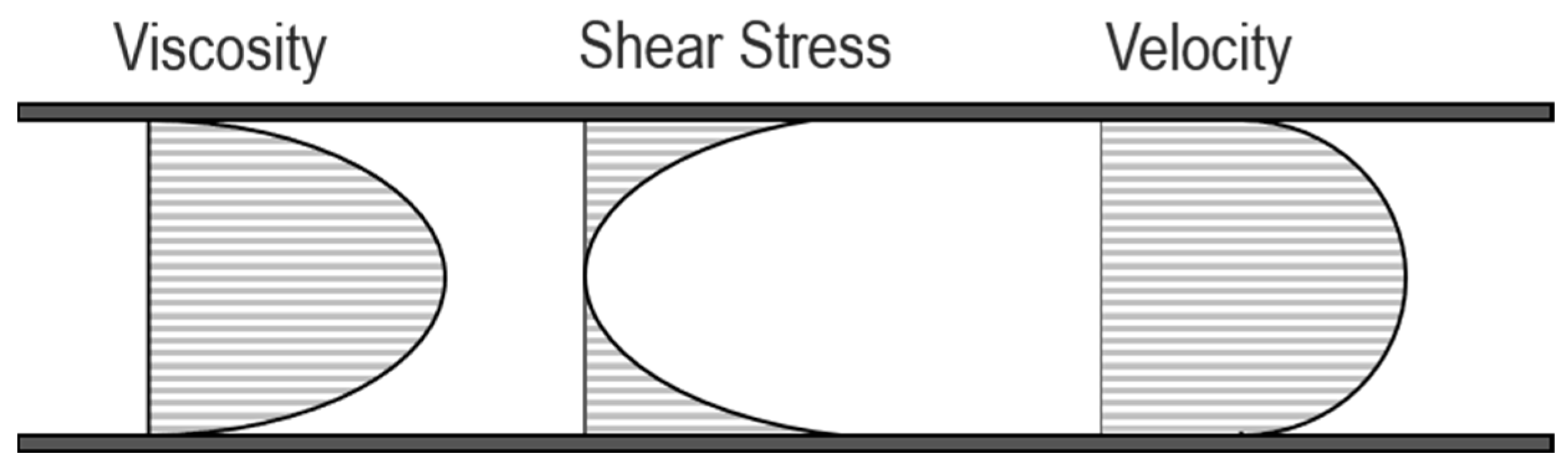

1.2.3. Behavior of Fibers in Plastic Melt

1.2.4. Effect of Material and Process Parameter on Fiber Orientation

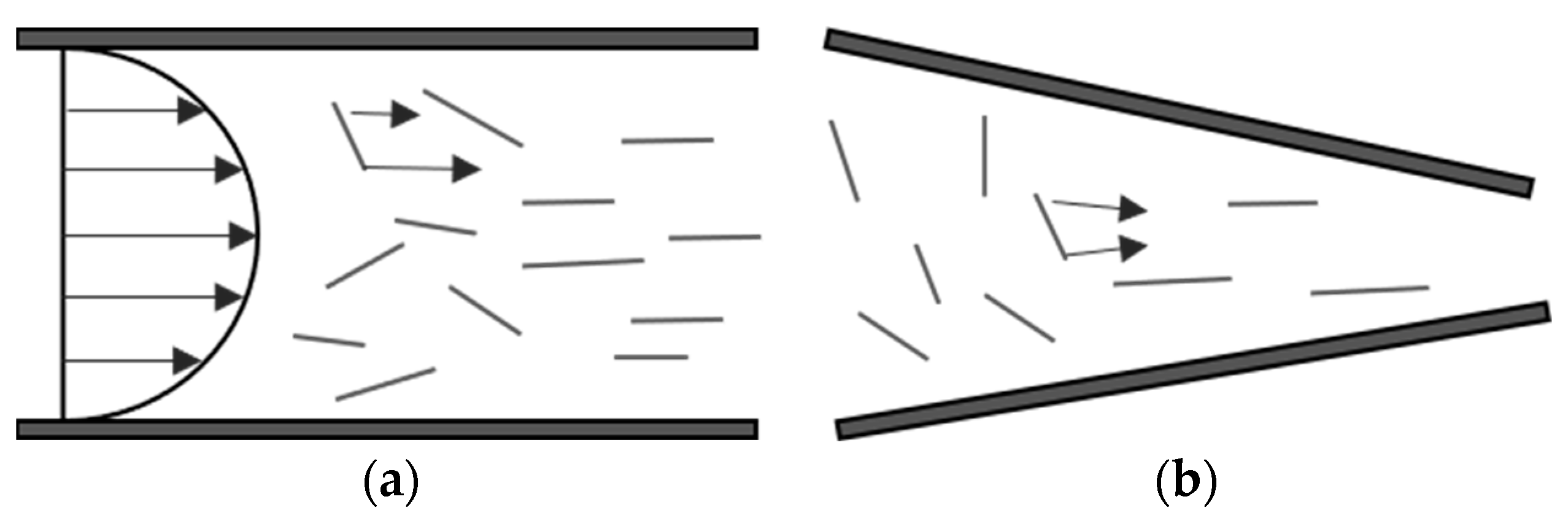

1.2.5. Current State of Discontinuous Fiber Alignment

1.3. The Circular Recycling Concept

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

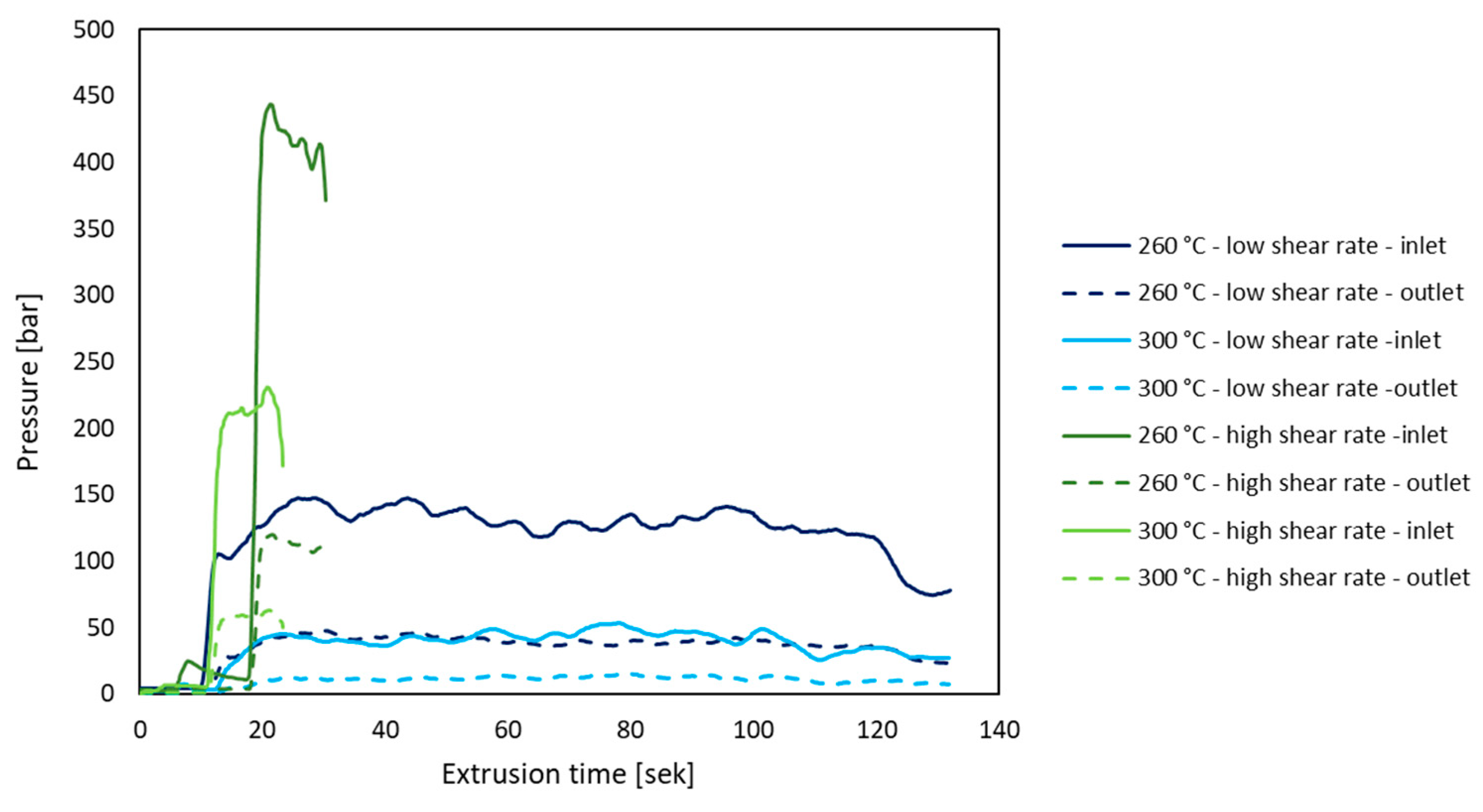

3.1. Fiber Orientation along the Melt Flow

3.2. Fiber Shortening

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, F. Environmental and Cost Analysis of Carbon Fibre Composites Recycling. Ph.D. Thesis, Universtity of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, S. Organoblech-Verschnitte recyceln: Faserverstärkte Thermoplaste mechanisch rezyklieren und in die Produktion zurückführen. Kunststoffe 2021, 1, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Harmina, T.; Hartikainen, J.; Lindner, M. Long Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites in Automotive Applications. In Polymer Composites: From Nano- to Macro-Scale; Friedrich, K., Fakirov, S., Zhang, Z., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Krauklis, A.E.; Karl, C.W.; Gagani, A.I.; Jørgensen, J.K. Composite Material Recycling Technology—State-of-the-Art and Sustainable Development for the 2020s. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotz, F.; Kling, M.M.; Langner, F.M.; Hohrath, P.; Born, H.; Feil, A. Entwicklung Eines Konzepts und Maßnahmen für Einen Ressourcensichernden Rückbau von Windenergieanlagen; Federal Environment Agency: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2019.

- Ashby, M.F. Material Selection in Mechanical Design, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Waltham, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- AVK Industrievereinigung Verstärkter Kunststoffe. Der Markt für Glasfaserverstärkte Kunststoffe 2019; AVK Industrievereinigung Verstärkter Kunststoffe: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Witten, E.; Mathes, V. The Market for Glass Fibre Reinforced Plastics (GRP) in 2020; AVK Industrievereinigung Verstärkter Kunststoffe: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Klimaschutzprogramm 2030 der Bundesregierung zur Umsetzung des Klimaschutzplans 2050, 2019. Available online: https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Downloads/Klimaschutz/klimaschutzprogramm-2030-der-bundesregierung-zur-umsetzung-des-klimaschutzplans-2050.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4 (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- OECD. Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060; OECD: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenstein, G.W. Faserverbund-Kunststoffe. Werkstoffe—Verarbeitung—Eigenschaften, 2nd ed.; Hanser: München, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, C.L., III. Fundamentals of Fiber Orientation. Description, Measurement and Prediction; Hanser Publishers: Munich, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Laun, H.M. Orientation effects and rheology of short glass fiber-reinforced thermoplastics: Polymer Science. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1984, 262, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, T. Rheologie der Kunststoffe. Theorie und Praxis, 2nd ed.; Hanser: München, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.K.; Song, J.H. Rheological properties and fiber orientations of short fiber-reinforced plastics. J. Rheol. 1997, 41, 1061–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becraft, M.L.; Metzner, A.B. The rheology, fiber orientation, and processing behavior of fiber-filled fluids. J. Rheol. 1992, 36, 143–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, J.L. Glass fibre sizing: A review. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 127, 105619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, J.; Adzima, L. Sizing up the interphase: An insider’s guide to the science of sizing. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2001, 32, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.; Haag, M.; Gries, T.; Pico, D.; Wilms, C.; Seide, G.; Kleinholz, R.; Tiesler, H. Fibers, 12. Glass Fibers. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 6th ed.; Bohnet, M., Ullmann, F., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Skrabala, O.; Koslowski, T.; Haufe, S. Method for Influencing the Orientation of Fillers in a Plastic Melt During Production of a Moulding in an Injection Moulding Process; Universität Stuttgart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Azaiez, J.; Chiba, K.; Chinesta, F.; Poitou, A. State-of-the-Art on numerical simulation of fiber-reinforced thermoplastic forming processes. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2002, 9, 141–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Such, M.C.; Ward, C.; Potter, K. Aligned Discontinuous Fibre Composites: A Short History. J. Multifunct. Compos. 2014, 3, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, L.T.; Turner, T.A.; Martin, J.; Warrior, N.A. Fiber Alignment in Directed Carbon Fiber Preforms—A Feasibility Study. J. Compos. Mater. 2009, 43, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, T.; Imaeda, S. A dry aligning method of discontinuous carbon fibers and improvement of mechanical properties of discontinuous fiber composites. Adv. Manuf. Polym. Compos. Sci. 2016, 2, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, H.; Potter, K.D.; Wisnom, M.R. A novel manufacturing method for aligned discontinuous fibre composites (High Performance-Discontinuous Fibre method). Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2014, 65, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longana, M.L.; Yu, H.; Lee, J.; Pozegic, T.R.; Huntley, S.; Rendall, T.; Potter, K.D.; Hamerton, I. Quasi-Isotropic and Pseudo-Ductile Highly Aligned Discontinuous Fibre Composites Manufactured with the HiPerDiF (High Performance Discontinuous Fibre) Technology. Materials 2019, 12, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tang, J.; Swolfs, Y.; Longana, M.L.; Yu, H.; Wisnom, M.R.; Lomov, S.V.; Gorbatikh, L. Hybrid composites of aligned discontinuous carbon fibers and self-reinforced polypropylene under tensile loading. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 123, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntley, S.; Rendall, T.; Longana, M.; Pozegic, T.; Potter, K.; Hamerton, I. Validation of a smoothed particle hydrodynamics model for a highly aligned discontinuous fibre composites manufacturing process. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 196, 108152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajangsawasdi, N.; Nguyen, D.H.; Hamerton, I.; Woods, B.K.S.; Ivanov, D.S.; Longana, M.L. Steering Potential for Printing Highly Aligned Discontinuous Fibre Composite Filament. Materials 2023, 16, 3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomason, J.L. Glass Fibre Sizing: A Review of Size Formulation Patents; James, L., Ed.; Thomason: Glasgow, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, P.H.; Tseng, H.-C.; Snawerdt, J.; Chang, Y.-J.; Yang, W.-H.; Hsu, C.-H. Prediction of fiber orientation distribution in injection molded parts using Moldex3D simulation. Polym. Compos. 2014, 35, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Low Level | High Level |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 260 °C | 300 °C |

| Shear rate | 100 1/s | 1000 1/s or 470 m/s |

| Nozzle thickness | 1 mm | 3 mm |

| Fiber bundle structure | Normal | Unstructured |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moritzer, E.; Tölle, L.; Greb, C.; Haag, M. Conceptions and Feasibility Study of Fiber Orientation in the Melt as Part of a Completely Circular Recycling Concept for Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastics. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs7070267

Moritzer E, Tölle L, Greb C, Haag M. Conceptions and Feasibility Study of Fiber Orientation in the Melt as Part of a Completely Circular Recycling Concept for Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastics. Journal of Composites Science. 2023; 7(7):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs7070267

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoritzer, Elmar, Lisa Tölle, Christoph Greb, and Markus Haag. 2023. "Conceptions and Feasibility Study of Fiber Orientation in the Melt as Part of a Completely Circular Recycling Concept for Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastics" Journal of Composites Science 7, no. 7: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs7070267

APA StyleMoritzer, E., Tölle, L., Greb, C., & Haag, M. (2023). Conceptions and Feasibility Study of Fiber Orientation in the Melt as Part of a Completely Circular Recycling Concept for Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastics. Journal of Composites Science, 7(7), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs7070267