Development and Mechanical Testing of Synthetic 3D-Printed Models of Healthy and Metastatic Vertebrae

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Evaluation of the repeatability of mechanical parameters across replicas of the same vertebra.

- Assessment of the influence of material composition and geometry on the mechanical behaviour of the synthetic models emulating healthy, pathological, and treated vertebrae.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Data

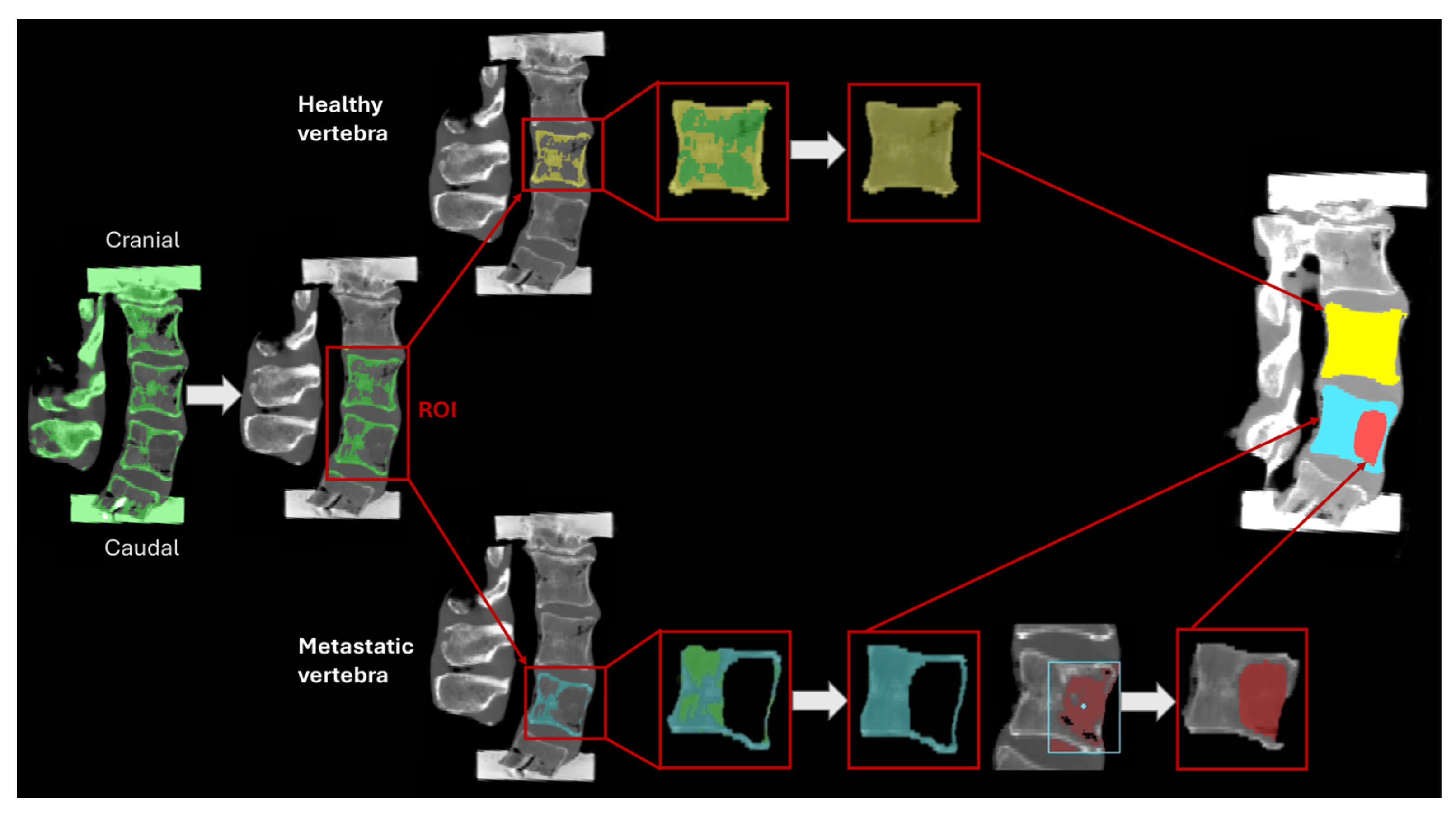

2.2. Segmentation

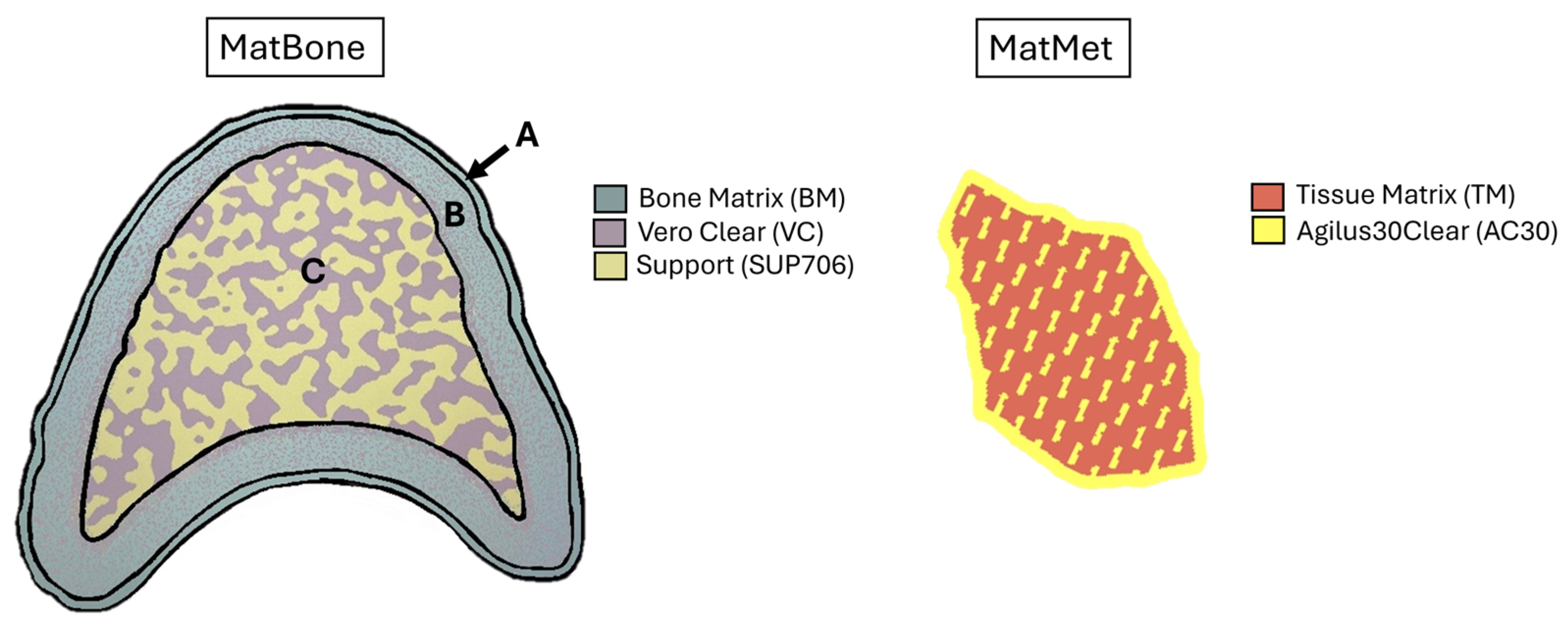

2.3. Material Assignment

- An outer layer (0.35 mm) made entirely of BoneMatrix (BM), an elastoplastic polymer with a Young’s modulus of around 250 MPa [28]. This layer provides shape memory and elastic recovery properties.

- A transitional layer (1.65 mm) made from a blend of 90% BM and 10% of VeroClear (VC) (Young’s modulus ≈ 500 MPa) [28].

- An inner porous layer composed of VC combined with a wax-support material (SUP706) (Young’s modulus ≈ 200 MPa), designed to emulate the architecture of trabecular bone.

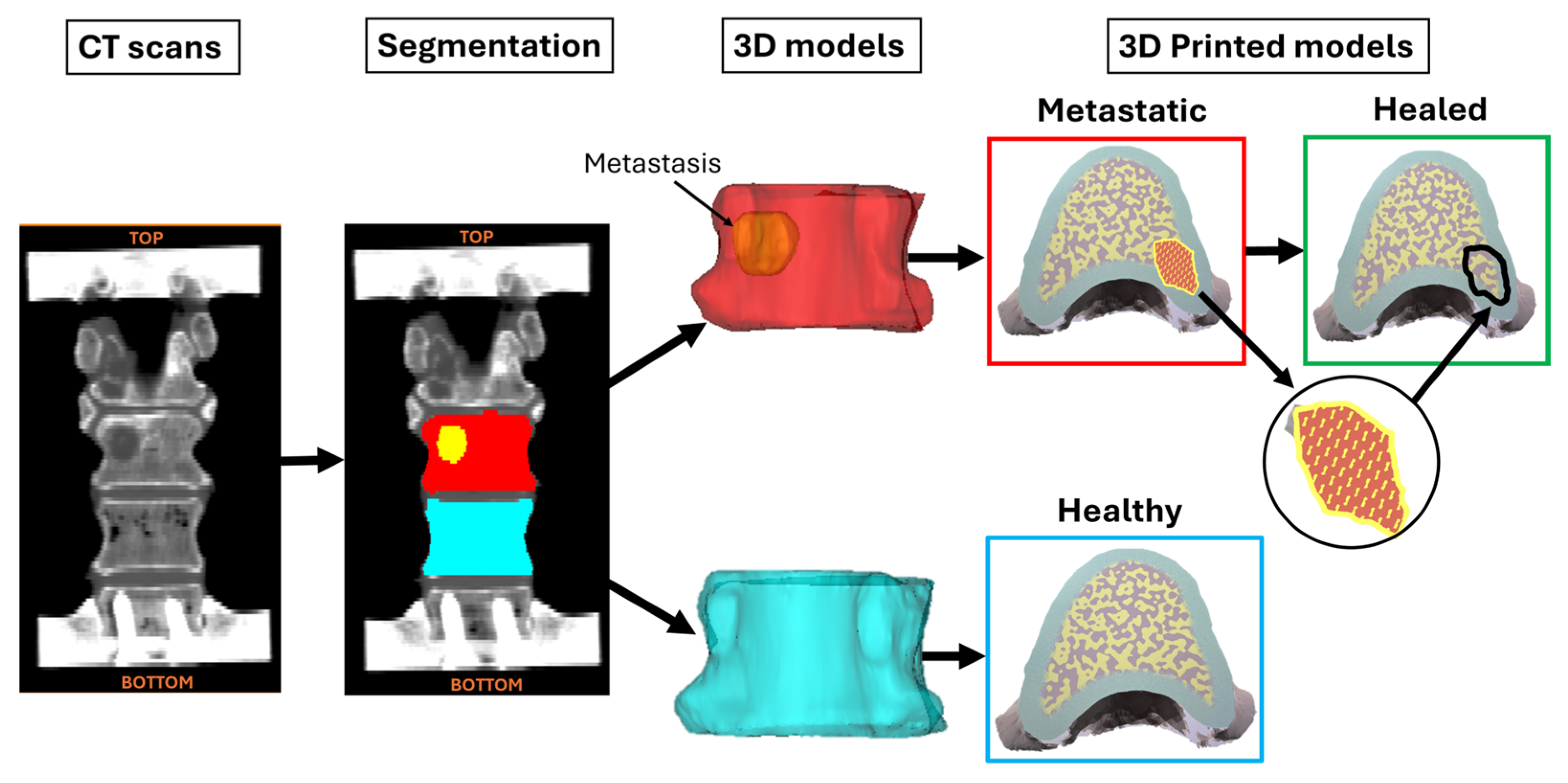

2.4. 3DP Models

- Healthy vertebrae, which had the geometry of the healthy vertebrae and were printed entirely with MatBone.

- Metastatic vertebrae, which had the geometry of the metastatic vertebrae and were printed using MatBone for the bone structure and MatMet for the metastatic lesions.

- Healed vertebrae, which had the same geometry as the metastatic models, but they were made exclusively of MatBone, thereby replacing the material used for the metastatic tissue with the material used for the healthy tissue.

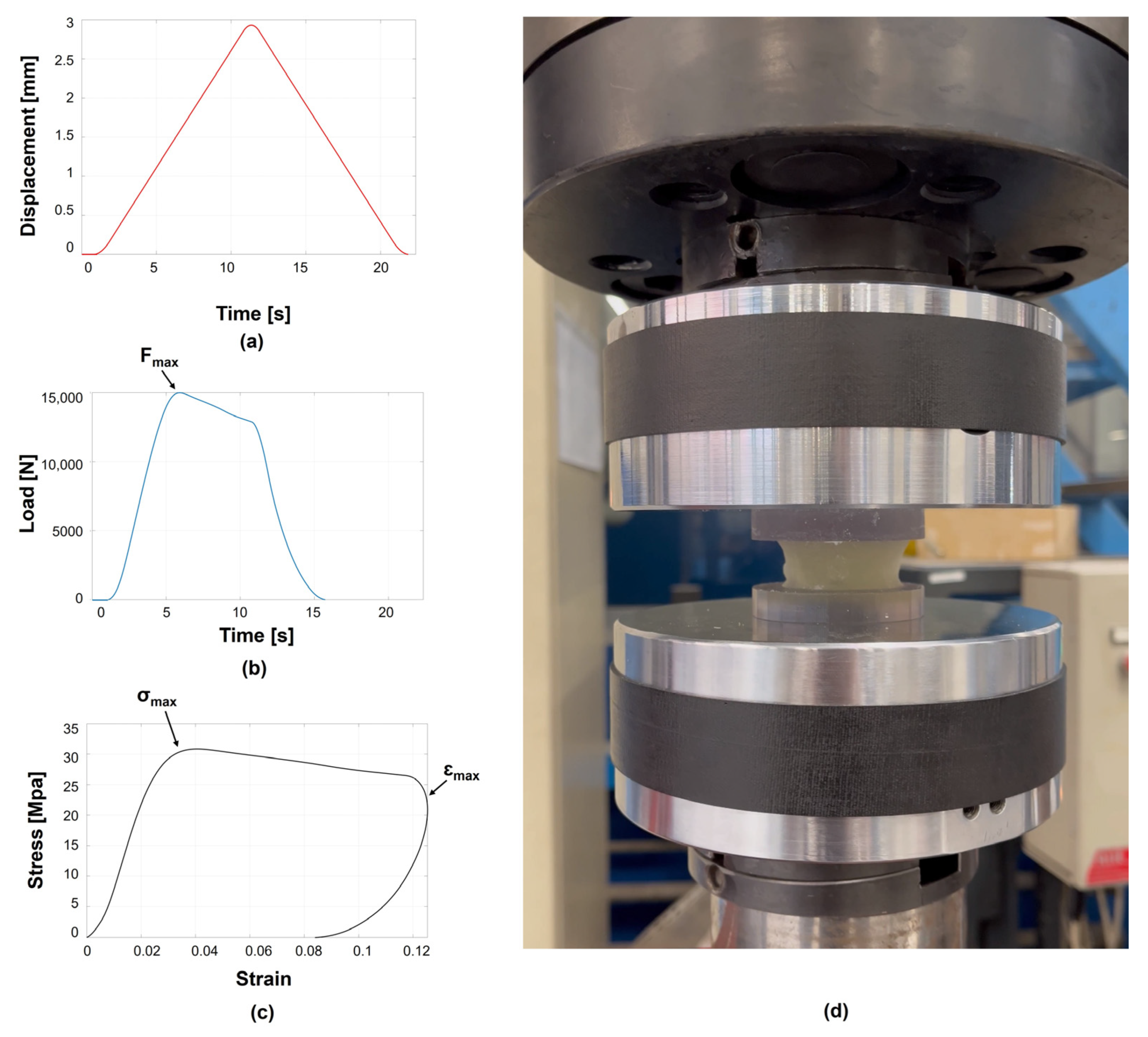

2.5. Mechanical Testing Protocol and Metrics

2.6. Statistical Analysis

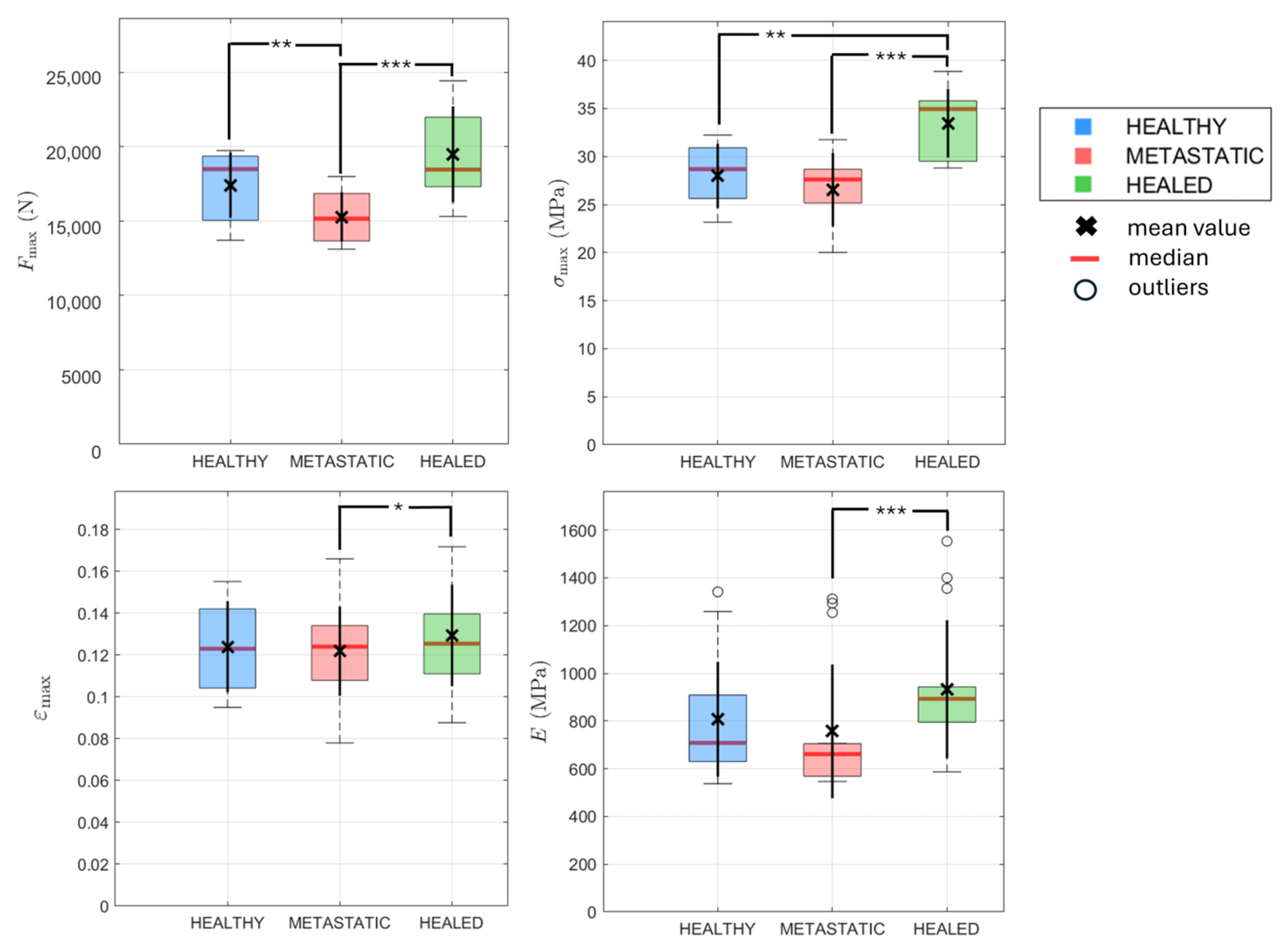

- To evaluate the material effect, Metastatic vs. Healed types were compared. The two groups were treated as paired, as both models were obtained from the same vertebrae but printed them in different ways. Therefore, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied to Fmax, σmax, and εmax, while paired t-test was applied to E.

- To evaluate the geometry effect, Healthy vs. Healed types were compared. The two groups were treated as independent since they are based on different vertebrae, therefore, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to Fmax, σmax, and εmax, while an independent t-test was applied to E.

- To evaluate the combined effect of material and geometry, Healthy vs. Metastatic types were compared. They were considered independent, hence the Mann-Whitney U test was used to Fmax, σmax, and εmax, while an independent t-test was applied to E.

3. Results

3.1. Geometrical Parameters

3.2. Repeatability of Mechanical Parameters on Vertebrae Replicas

3.3. Influence of Material Composition and Geometry on the Mechanical Behaviour

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| FE | Finite Element |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| HU | Hounsfield Unit |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| STL | Standard Tessellation Language |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| DAC | Digital Anatomy Creator |

| BM | BoneMatrix |

| VC | VeroClear |

| SUP706 | Support |

| TPMS | Triply Periodic Minimal Surface |

| TM | TissueMatrix |

| AC30 | Agilus30Clear |

| 3DP | Three-dimensional Printed |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| VB | Vertebral Body |

References

- Coleman, R.E.; Croucher, P.I.; Padhani, A.R.; Clézardin, P.; Chow, E.; Fallon, M.; Guise, T.; Colangeli, S.; Capanna, R.; Costa, L. Bone Metastases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2020, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrin, R.G.; Laxton, A.W. Metastatic Spine Disease: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Evaluation of Patients. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 15, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, P.; Connock, M.; Shyangdan, D.; Court, R.; Kandala, N.-B.; Clarke, A. A Systematic Review of Evidence on Malignant Spinal Metastases: Natural History and Technologies for Identifying Patients at High Risk of Vertebral Fracture and Spinal Cord Compression. Health Technol. Assess. 2013, 17, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbusera, F.; Qian, Z.; Casaroli, G.; Bassani, T.; Costa, F.; Schlager, B.; Wilke, H.-J. The Role of the Size and Location of the Tumors and of the Vertebral Anatomy in Determining the Structural Stability of the Metastatically Involved Spine: A Finite Element Study. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 11, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkalay, R.N. Effect of the Metastatic Defect on the Structural Response and Failure Process of Human Vertebrae: An Experimental Study. Clin. Biomech. 2015, 30, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanca, M.; Cavazzoni, G.; Dall’Ara, E. The Role of Bone Metastases on the Mechanical Competence of Human Vertebrae. Bone 2023, 173, 116814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanca, M.; Barbanti-Bròdano, G.; Cristofolini, L. The Size of Simulated Lytic Metastases Affects the Strain Distribution on the Anterior Surface of the Vertebra. J. Biomech. Eng. 2018, 140, 111005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, R.L. (Ed.) Metastatic Bone Disease: An Integrated Approach to Patient Care; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-52000-6. [Google Scholar]

- Whyne, C.M. Biomechanics of Metastatic Disease in the Vertebral Column. Neurol. Res. 2014, 36, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, F.; Ladeira, K.; Pinho, F.; Saraiva, N.; Bonito, N.; Pinto, L.; Gonçalves, F. Bone Metastases: An Overview. Oncol. Rev. 2017, 11, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, S.; Stadelmann, M.A.; Zysset, P.K.; Vashishth, D.; Alkalay, R.N. Influence of Metastatic Bone Lesion Type and Tumor Origin on Human Vertebral Bone Architecture, Matrix Quality, and Mechanical Properties. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020, 37, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavazzoni, G.; Dall’Ara, E.; Palanca, M. Microstructure of the Human Metastatic Vertebral Body. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 15, 1508504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanca, M.; Barbanti-Bròdano, G.; Marras, D.; Marciante, M.; Serra, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Dall’Ara, E.; Cristofolini, L. Type, Size, and Position of Metastatic Lesions Explain the Deformation of the Vertebrae under Complex Loading Conditions. Bone 2021, 151, 116028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.C.; Campello, L.B.B.; Ryan, M.; Rochester, J.; Viceconti, M.; Dall’Ara, E. Effect of Size and Location of Simulated Lytic Lesions on the Structural Properties of Human Vertebral Bodies, a Micro-Finite Element Study. Bone Rep. 2020, 12, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadelmann, M.A.; Schenk, D.E.; Maquer, G.; Lenherr, C.; Buck, F.M.; Bosshardt, D.D.; Hoppe, S.; Theumann, N.; Alkalay, R.N.; Zysset, P.K. Conventional Finite Element Models Estimate the Strength of Metastatic Human Vertebrae despite Alterations of the Bone’s Tissue and Structure. Bone 2020, 141, 115598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejo-Otero, A.; Buj-Corral, I.; Fenollosa-Artés, F. 3D Printing in Medicine for Preoperative Surgical Planning: A Review. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, A.; Mehta, N.; Garg, B. 3D Printing in Spine Care: A Review of Current Applications. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2022, 35, 102044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolino, G.; Coato, D.; Forni, R.; Boretti, G.; Ciliberti, F.K.; Gargiulo, P. Designing a Synthetic 3D-Printed Knee Cartilage: FEA Model, Micro-Structure and Mechanical Characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2023, 14, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, P.; Victor, J.; Gemmel, P.; Annemans, L. 3D-Printing Techniques in a Medical Setting: A Systematic Literature Review. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2016, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, C.; Fontenay, S.; Van Den Brink, H.; Pineau, J.; Prognon, P.; Martelli, N. Evaluation of 3D Printing Costs in Surgery: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2020, 36, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzner, F.; Neupetsch, C.; Carabello, A.; Pietsch, M.; Wendler, T.; Drossel, W.-G. Biomechanical Validation of Additively Manufactured Artificial Femoral Bones. BMC Biomed. Eng. 2022, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahbeh, J.M.; Hookasian, E.; Lama, J.; Alam, L.; Park, S.; Sangiorgio, S.N.; Ebramzadeh, E. An Additively Manufactured Model for Preclinical Testing of Cervical Devices. JOR SPINE 2024, 7, e1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Baca Lopez, D.M.; Ahmad, R. Scientometric Analysis and Systematic Review of Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing of Polymers. Polymers 2021, 13, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiee, M. Multi Material 3D and 4D Printing: A Survey. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, Y.L.; Peng, C.; Pille, P.; Leary, M.; Tran, P. PolyJet 3D Printing of Composite Materials: Experimental and Modelling Approach. JOM 2020, 72, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, A.; Chen, P.-Y. Mechanical Properties of Additively Manufactured Multi-Material Stiff-Soft Interfaces: Guidelines to Manufacture Complex Interface Composites with Tunable Properties. Mater. Des. 2024, 238, 112677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, R.; Calderonel, D.; Coato, D.; Dolino, G.; Cesarelli, G.; Ricciardi, C.; Cesarelli, M.; Gargiulo, P. Towards Bio-Mimetic 3D Printable Human Anatomies. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for eXtended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE), St Albans, UK, 21 October 2024; pp. 1016–1021. [Google Scholar]

- García-Collado, A.; Blanco, J.M.; Gupta, M.K.; Dorado-Vicente, R. Advances in Polymers Based Multi-Material Additive-Manufacturing Techniques: State-of-Art Review on Properties and Applications. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 50, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.; Grunert, R.; Mohr, F.W.; Falk, V. 3D-Imaging of Cardiac Structures Using 3D Heart Models for Planning in Heart Surgery: A Preliminary Study. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2008, 7, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Chen, L.; Guan, X.; Ye, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, L. Surgical Planning, Three-Dimensional Model Surgery and Preshaped Implants in Treatment of Bilateral Craniomaxillofacial Post-Traumatic Deformities. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 1138.e1–1138.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hangartner, T.N. Thresholding Technique for Accurate Analysis of Density and Geometry in QCT, pQCT and ÌCT Images. J. Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2007, 7, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eijnatten, M.; Van Dijk, R.; Dobbe, J.; Streekstra, G.; Koivisto, J.; Wolff, J. CT Image Segmentation Methods for Bone Used in Medical Additive Manufacturing. Med. Eng. Phys. 2018, 51, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, H.; Jin, Y.; Yang, D.; Wier, C.; Minard, A.; Dahotre, N.B.; Neogi, A. Manufacturing and Characterization of Hybrid Bulk Voxelated Biomaterials Printed by Digital Anatomy 3D Printing. Polymers 2020, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forni, R.; Pavan, G.; Gunnarsson, A.; Ricciardi, C.; Corsi, C.; Gargiulo, P. Advanced 3D Printing of Patient-Specific Human Heart for Improved Surgical Planning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for eXtended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE), Milano, Italy, 25 October 2023; pp. 473–478. [Google Scholar]

- La Barbera, L.; Villa, T.; Costa, F.; Boschetti, F.; De Robertis, M.; Anselmi, L.; Capo, G.; Pancetti, S.; Fornari, M. Poroelastic Characterization of Human Vertebral Metastases to Inform a Transdisciplinary Assessment of Spinal Tumors. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyne, C.M.; Hu, S.S.; Workman, K.L.; Lotz, J.C. Biphasic Material Properties of Lytic Bone Metastases. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2000, 28, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, Y.L.; Yeong, W.Y. Shape Recovery Effect of 3D Printed Polymeric Honeycomb: This Paper Studies the Elastic Behaviour of Different Honeycomb Structures Produced by PolyJet Technology. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2015, 10, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsi, A.; Pullen, A.D.; Latham, J.P.; Bowen, J.; Carlsson, M.; Stitt, E.H.; Marigo, M. Full Deflection Profile Calculation and Young’s Modulus Optimisation for Engineered High Performance Materials. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machin, D.; Campbell, M.J.; Walters, S.J. Medical Statistics; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, D.; Julias, M.; Nauman, E. Biological Variability in Biomechanical Engineering Research: Significance and Meta-Analysis of Current Modeling Practices. J. Biomech. 2014, 47, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.C.; Eltes, P.; Lazary, A.; Varga, P.P.; Viceconti, M.; Dall’Ara, E. Biomechanical Assessment of Vertebrae with Lytic Metastases with Subject-Specific Finite Element Models. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 98, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, T.S.; Bell, J.S.; Pejcic, M.R.; Tehranzadeh, J.; Keyak, J.H. Mechanical Properties, Density and Quantitative CT Scan Data of Trabecular Bone with and without Metastases. J. Biomech. 2004, 37, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, L.; Teutelink, A.; Van Tilborg, F.A.J.B.; De Jongh, M.A.C.; Lansink, K.W.W.; Bemelman, M. Validation Study of 3D-Printed Anatomical Models Using 2 PLA Printers for Preoperative Planning in Trauma Surgery, a Human Cadaver Study. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2019, 45, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, L.; Falcinelli, C. On the Human Vertebra Computational Modeling: A Literature Review. Meccanica 2022, 57, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juergensen, L.; Rischen, R.; Hasselmann, J.; Toennemann, M.; Pollmanns, A.; Gosheger, G.; Schulze, M. Insights into Geometric Deviations of Medical 3d-Printing: A Phantom Study Utilizing Error Propagation Analysis. 3D Print. Med. 2024, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | Donor | Primary Tumour | Sex | Age (yr) | BMI (kg/m2) | Healthy Vertebra | Metastatic Vertebra |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | A | Nasopharyngeal | M | 72 | 16 | T7 | T6 |

| #2 | B | Breast | F | 82 | 22 | T7 | T6 |

| #3 | B | Breast | F | 82 | 22 | L3 | L4 |

| #4 | C | Adenocarcinoma | F | 62 | 57 | T6 | T5 |

| #5 | D | Breast | F | 55 | 17 | T7 | T8 |

| ID | Typologies | Minimum Cross-Sectional Area (mm2) | Volume of the Vertebra (mm3) | Volume of the Metastasis (mm3) (VB%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | Healthy | 532 | 11,645 | - |

| Metastatic | 486 | 10,059 | 526 (4.9) | |

| Healed | 486 | 10,585 | - | |

| #2 | Healthy | 570 | 12,363 | - |

| Metastatic | 493 | 10,481 | 737 (6.6) | |

| Healed | 493 | 11,218 | - | |

| #3 | Healthy | 848 | 25,810 | - |

| Metastatic | 828 | 23,185 | 3806 (14.1) | |

| Healed | 828 | 26,991 | - | |

| #4 | Healthy | 606 | 14,323 | - |

| Metastatic | 524 | 10,280 | 696 (6.3) | |

| Healed | 524 | 10,976 | - | |

| #5 | Healthy | 598 | 13,970 | - |

| Metastatic | 623 | 13,980 | 912 (6.1) | |

| Healed | 623 | 14,892 | - |

| ID | Fmax (kN) | σmax (MPa) | εmax | E (MPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | #1 | 15.2 (13.7–16.2) | 28.7 (25.8–30.5) | 0.14 (0.14–0.14) | 1259 (1006–1499) |

| #2 | 14.8 (14.6–15.0) | 26.1 (25.6–26.3) | 0.12 (0.10–0.14) | 655 (643–664) | |

| #3 | 19.7 (19.6–19.7) | 23.2 (23.2–23.3) | 0.10 (0.09–0.11) | 626 (626–627) | |

| #4 | 18.7 (18.2–19.5) | 30.8 (30.1–32.2) | 0.15 (0.14–0.16) | 708 (537–742) | |

| #5 | 18.8 (18.5–18.9) | 31.4 (30.9–31.6) | 0.11 (0.10–0.12) | 906 (871–908) | |

| Metastatic | #1 | 15.2 (15.0–15.4) | 31.2 (30.8–31.7) | 0.12 (0.12–0.13) | 1294 (1258–1323) |

| #2 | 13.7 (13.7–13.8) | 27.8 (27.7–28.0) | 0.12 (0.10–0.13) | 699 (695–706) | |

| #3 | 16.7 (16.6–17.0) | 20.1 (20.0–20.5) | 0.09 (0.08–0.11) | 561 (546–568) | |

| #4 | 13.4 (13.1–13.7) | 25.6 (25.0–26.1) | 0.14 (0.14–0.17) | 572 (549–584) | |

| #5 | 17.2 (16.9–18.0) | 27.6 (27.2–28.9) | 0.12 (0.11–0.14) | 661 (658–695) | |

| Healed | #1 | 18.5 (17.9–18.9) | 37.9 (36.8–38.9) | 0.12 (0.12–0.13) | 1400 (1328–1499) |

| #2 | 17.6 (17.2–17.6) | 35.7 (34.9–35.8) | 0.13 (0.09–0.14) | 942 (933–941) | |

| #3 | 24.3 (23.8–24.4) | 29.3 (28.8–29.5) | 0.10 (0.10–0.11) | 803 (791–807) | |

| #4 | 15.5 (15.3–15.9) | 29.5 (29.2–30.4) | 0.17 (0.16–0.17) | 595 (589–620) | |

| #5 | 21.8 (21.5–22.0) | 35.0 (34.6–35.4) | 0.13 (0.12–0.14) | 893 (873–900) |

| ID | Fmax | σmax | εmax | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | #1 | 8.4% | 8.4% | 1.2% | 14.6% |

| #2 | 1.4% | 1.4% | 19.0% | 1.5% | |

| #3 | 0.2% | 0.2% | 5.7% | 0.1% | |

| #4 | 3.5% | 3.5% | 7.0% | 16.5% | |

| #5 | 1.1% | 1.1% | 6.0% | 2.5% | |

| Metastatic | #1 | 1.5% | 1.5% | 0.6% | 2.3% |

| #2 | 0.6% | 0.6% | 10.9% | 1.0% | |

| #3 | 1.3% | 1.3% | 15.4% | 2.0% | |

| #4 | 2.1% | 2.1% | 9.7% | 2.9% | |

| #5 | 3.2% | 3.2% | 9.4% | 2.8% | |

| Healed | #1 | 2.7% | 2.7% | 0.9% | 7.2% |

| #2 | 1.3% | 1.3% | 23.3% | 0.6% | |

| #3 | 1.3% | 1.3% | 3.0% | 1.0% | |

| #4 | 2.0% | 2.0% | 3.5% | 2.7% | |

| #5 | 1.1% | 1.1% | 6.0% | 1.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bruno, D.; Forni, R.; Palanca, M.; Cristofolini, L.; Gargiulo, P. Development and Mechanical Testing of Synthetic 3D-Printed Models of Healthy and Metastatic Vertebrae. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9110373

Bruno D, Forni R, Palanca M, Cristofolini L, Gargiulo P. Development and Mechanical Testing of Synthetic 3D-Printed Models of Healthy and Metastatic Vertebrae. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(11):373. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9110373

Chicago/Turabian StyleBruno, Daniela, Riccardo Forni, Marco Palanca, Luca Cristofolini, and Paolo Gargiulo. 2025. "Development and Mechanical Testing of Synthetic 3D-Printed Models of Healthy and Metastatic Vertebrae" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 11: 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9110373

APA StyleBruno, D., Forni, R., Palanca, M., Cristofolini, L., & Gargiulo, P. (2025). Development and Mechanical Testing of Synthetic 3D-Printed Models of Healthy and Metastatic Vertebrae. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(11), 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9110373