Underwater Drone-Enabled Wireless Communication Systems for Smart Marine Communications: A Study of Enabling Technologies, Opportunities, and Challenges

Highlights

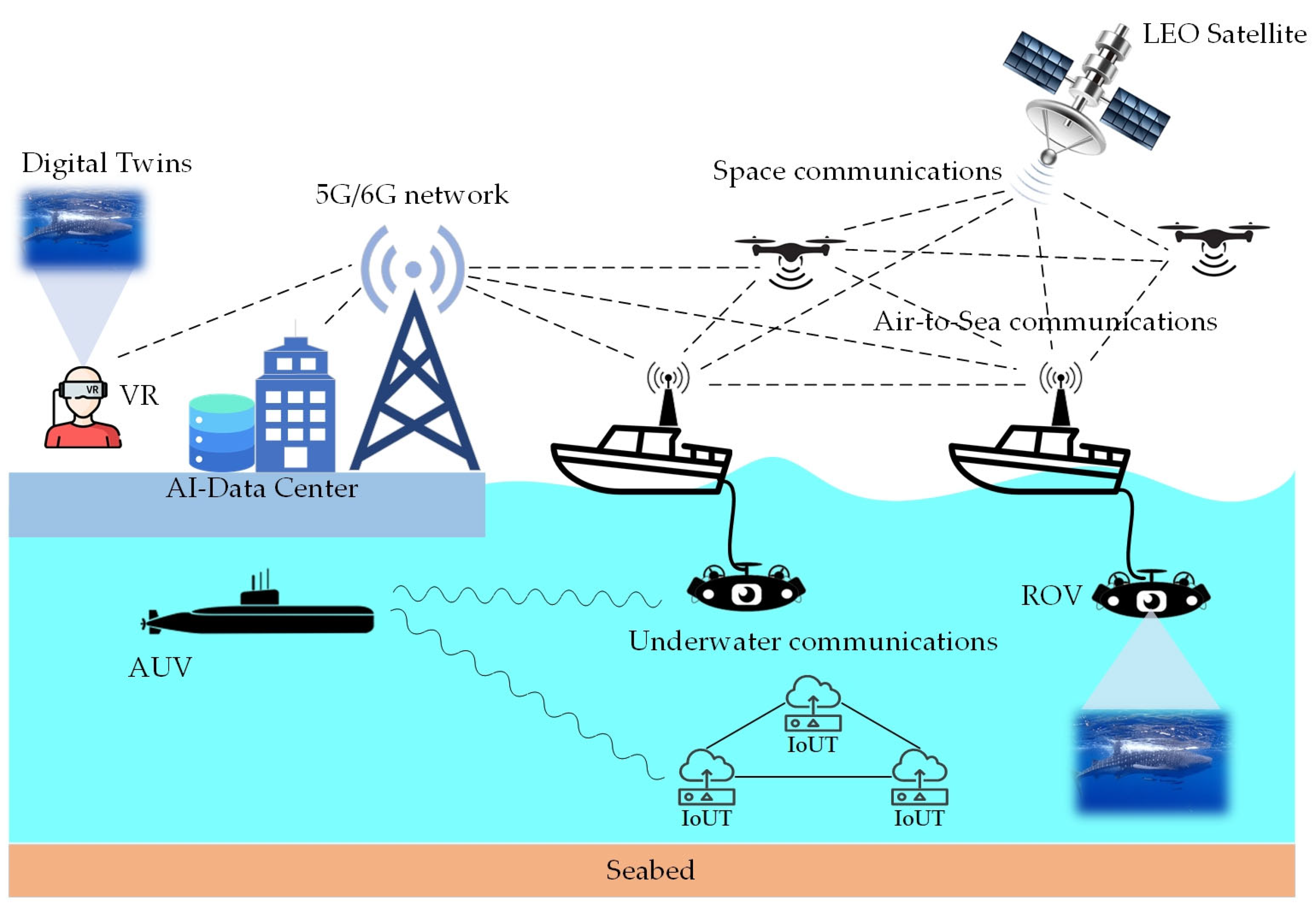

- This paper reviews underwater wireless communication methods, including acoustic, optical, and RF communication, in marine applications, and explores the potential of existing underwater drones.

- This paper examines the opportunities and challenges of hybrid wireless communication systems for underwater drones.

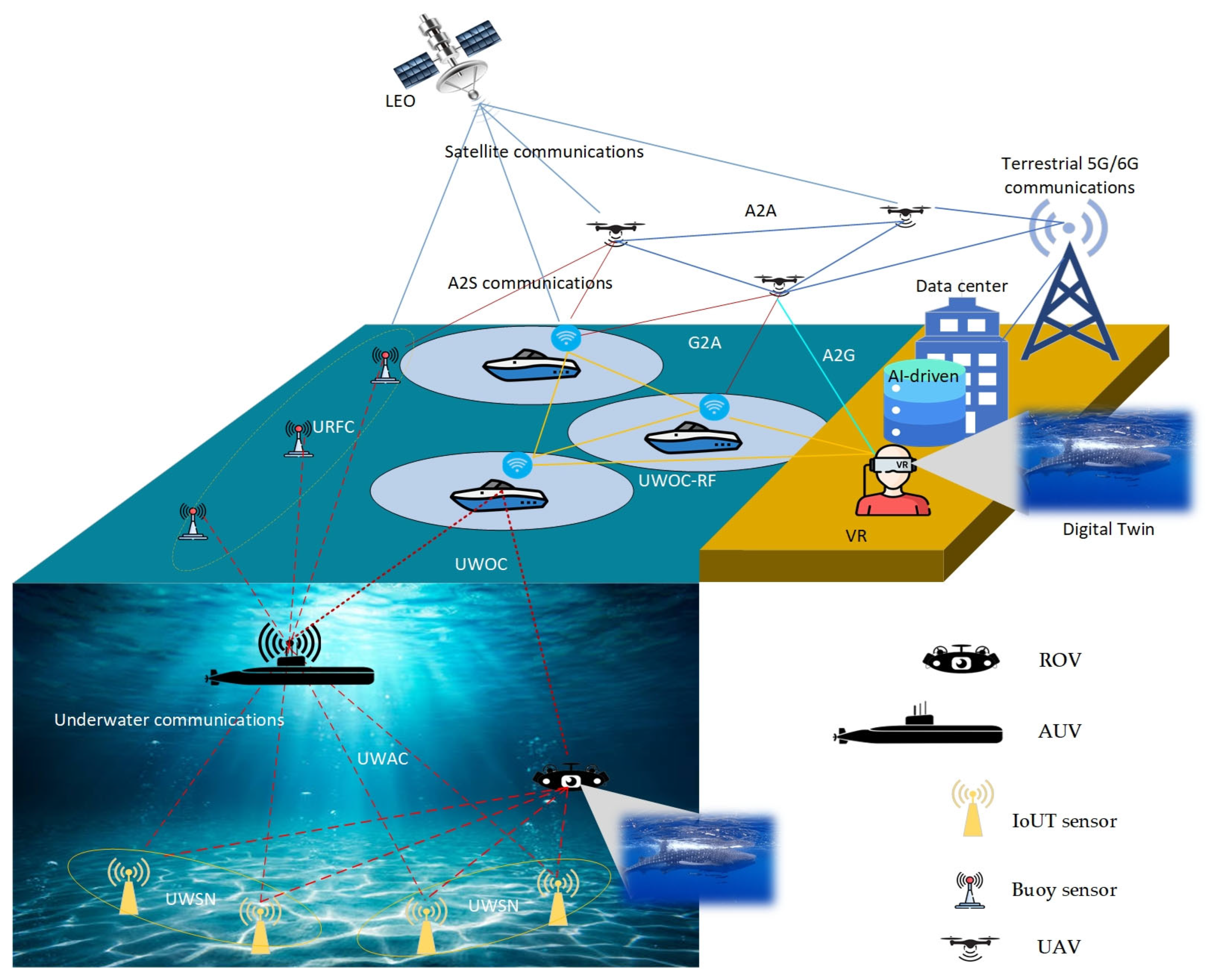

- This paper considers the integration of underwater drones, IoUT, AI-driven data, VR, and DT for smart marine communications.

Abstract

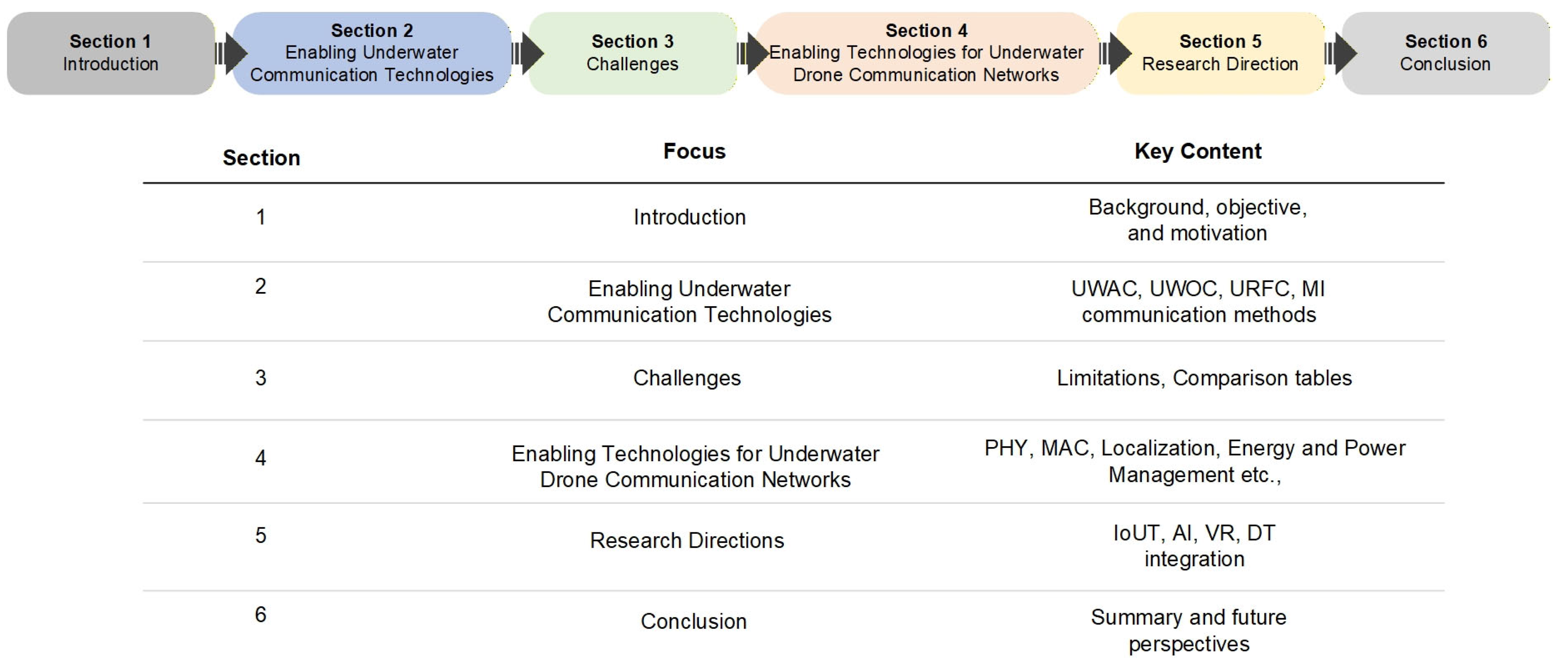

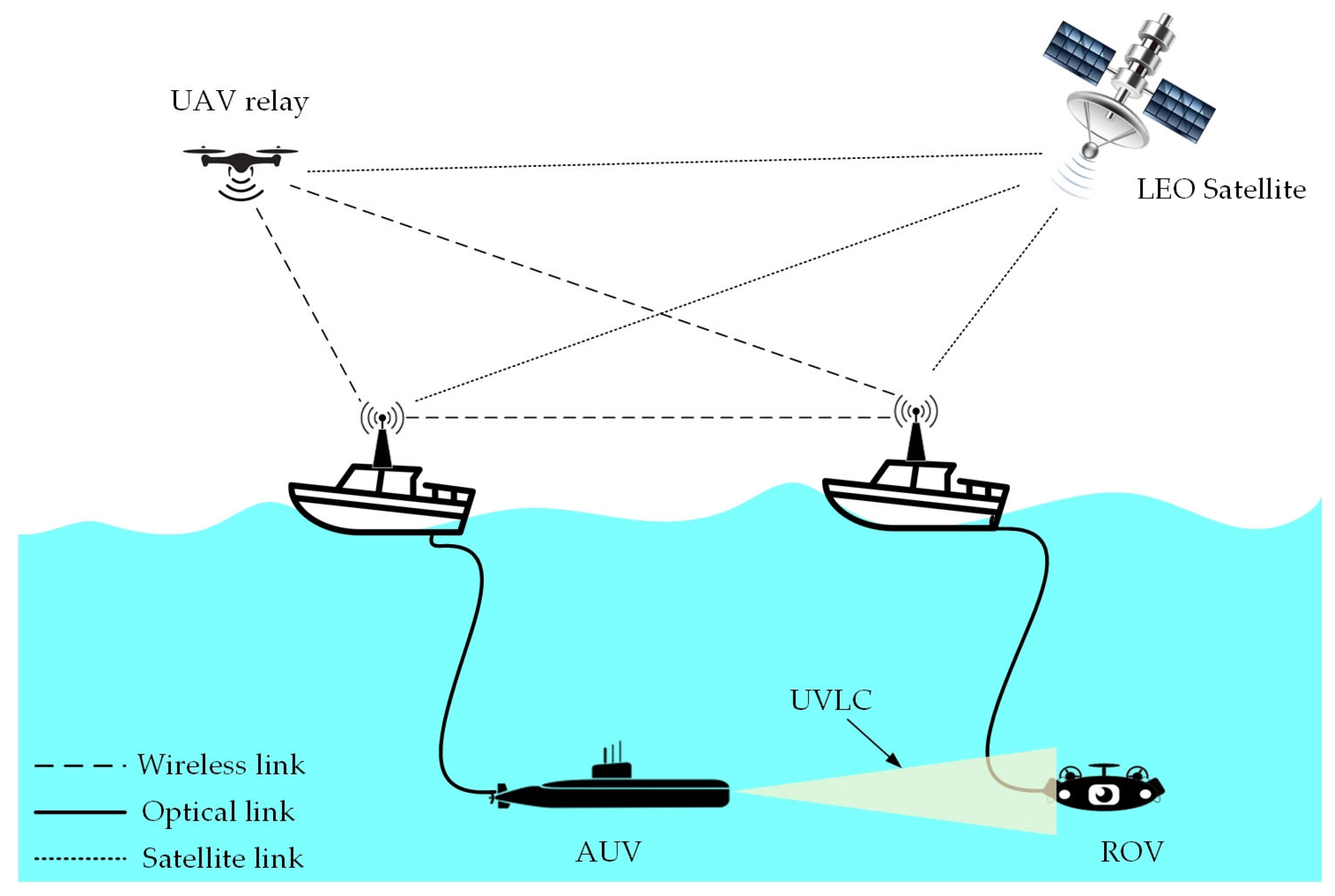

1. Introduction

- To review underwater wireless communication methods, including acoustic, optical, RF, and MI communication, in marine applications, and to explore the potential of existing underwater drones.

- To examine the opportunities and challenges of hybrid wireless communication systems for underwater drones.

- To identify future research directions, where we consider the integration of underwater drone, IoUT, AI-driven data, VR, and DT for smart marine communications.

2. Enabling Underwater Communication Technologies

2.1. Acoustic Communications

2.1.1. Underwater Wireless Acoustic Communication

2.1.2. UWAC for Underwater Drones

2.2. Optical Communications

2.2.1. Underwater Wireless Optical Communication

2.2.2. UWOC for Underwater Drones

2.3. RF Communications

2.3.1. Underwater RF Communication

2.3.2. URFC for Underwater Drones

2.4. MI Communications

3. Challenges

3.1. Hybrid Communication Systems

3.1.1. UAWC-UWOC

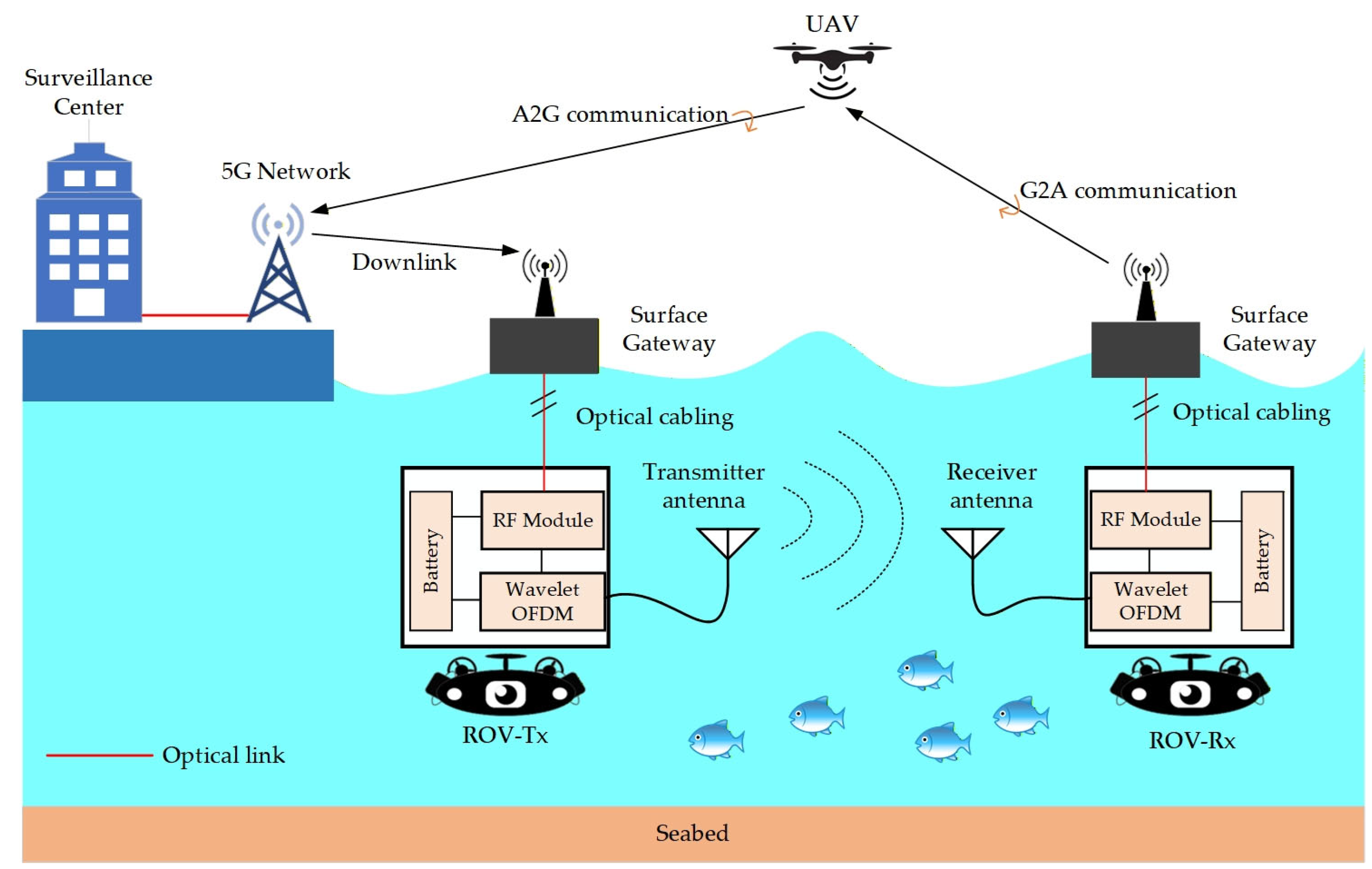

3.1.2. UWOC-RF

3.1.3. Hybrid Underwater Communication Mathematics Model

3.1.4. Multimodal System

3.2. Role of Underwater Drones in Smart Marine Applications

3.2.1. Pollution Detection

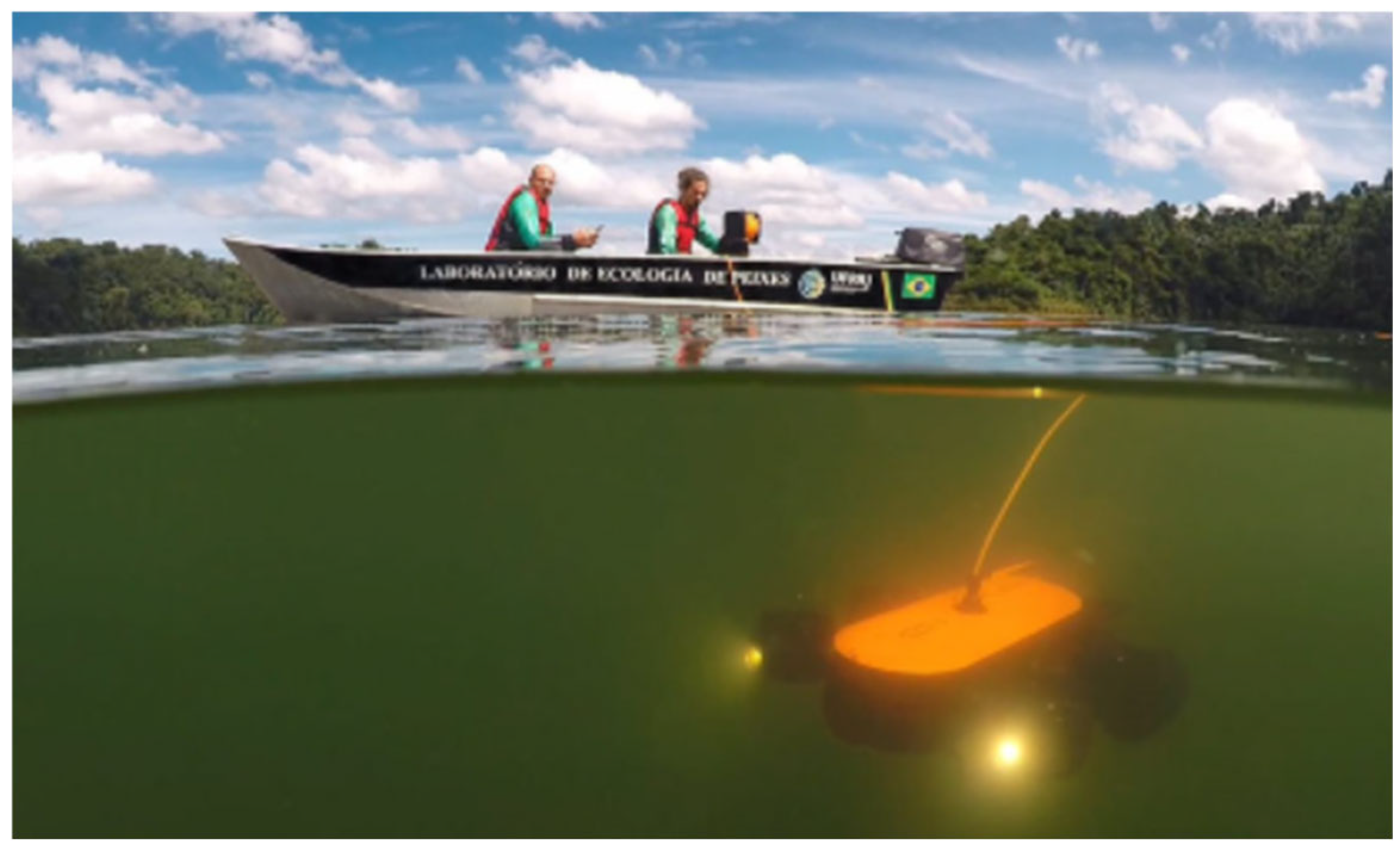

3.2.2. Biodiversity Assessment

3.2.3. Oil and Gas Exploration

3.2.4. Maritime Security

3.3. Cybersecurity and Eavesdropping Risks in Underwater Networks

4. Enabling Technologies for Underwater Drone Communication Networks

4.1. Physical Layer Enabling Technologies

4.2. Medium Access Control and Network Layer Technologies

4.3. Localization and Synchronization Technologies

4.4. Energy and Power Management Technologies

4.5. Intelligent and Adaptive Technologies

4.6. Emerging and Hybrid Enabling Technologies

5. Research Directions

5.1. IoUT

5.1.1. Communication Technologies and Challenges

5.1.2. Energy Efficiency and AUV/ROV Assistance

5.1.3. Data Management and Big Marine Data

5.1.4. Applications and Future Directions

5.2. AI-Driven Data

5.2.1. Autonomous Navigation and Control

5.2.2. Environmental Monitoring and Protection

5.2.3. Search and Rescue Operations

5.2.4. AI-Driven Underwater Drones

5.3. VR and Digital Twin

5.3.1. Digital Twin Technology in Underwater Drones

5.3.2. VR Applications

5.4. AI and Digital Twin Implementation

5.5. Integration of Underwater Drones, IoUT, AI, VR, and Digital Twin in Smart Marine Communications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, S. Marine internet for internetworking in oceans: A tutorial. Future Internet 2019, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, K.; Xing, W.; Li, H.; Yang, Z. Applications, evolutions, and challenges of drones in maritime transport. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji-Yong, L.; Hao, Z.; Hai, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhaoliang, W.; Lei, W. Design and vision based autonomous capture of sea organism with absorptive type remotely operated vehicle. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 73871–73884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Banna, A.A.A.; Wu, K.; ElHalawany, B.M. Opportunistic cooperative transmission for underwater communication based on the Water’s key physical variables. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 20, 2792–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, R.; Alraie, H.; Hasaba, R.; Eguchi, K.; Matsushima, T.; Fukumoto, Y.; Ishii, K. Performance analysis of underwater radiofrequency communication in seawater: An experimental study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra, S.; Lloret, J.; Jimenez, J.M.; Parra, L. Underwater acoustic modems. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 16, 4063–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Fu, S.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Y.; Cheng, J. A survey of underwater optical wireless communications. IEEE Commu. Surv. Tutor. 2016, 19, 204–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hott, M.; Hoeher, P.A. Underwater communication employing high-sensitive magnetic field detectors. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 177385–177394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Heldal, R.; Lima, K.; Oyetoyan, T.D.; Pelliccione, P.; Kristensen, L.M.; Hoydal, K.W.; Reiersgaard, P.S.; Kvinnsland, Y. Engineering challenges of stationary wireless smart ocean observation systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 14712–14724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharidis, T.; Kavallieratou, E. Underwater communication technologies: A review. Telecom. Syst. 2025, 88, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

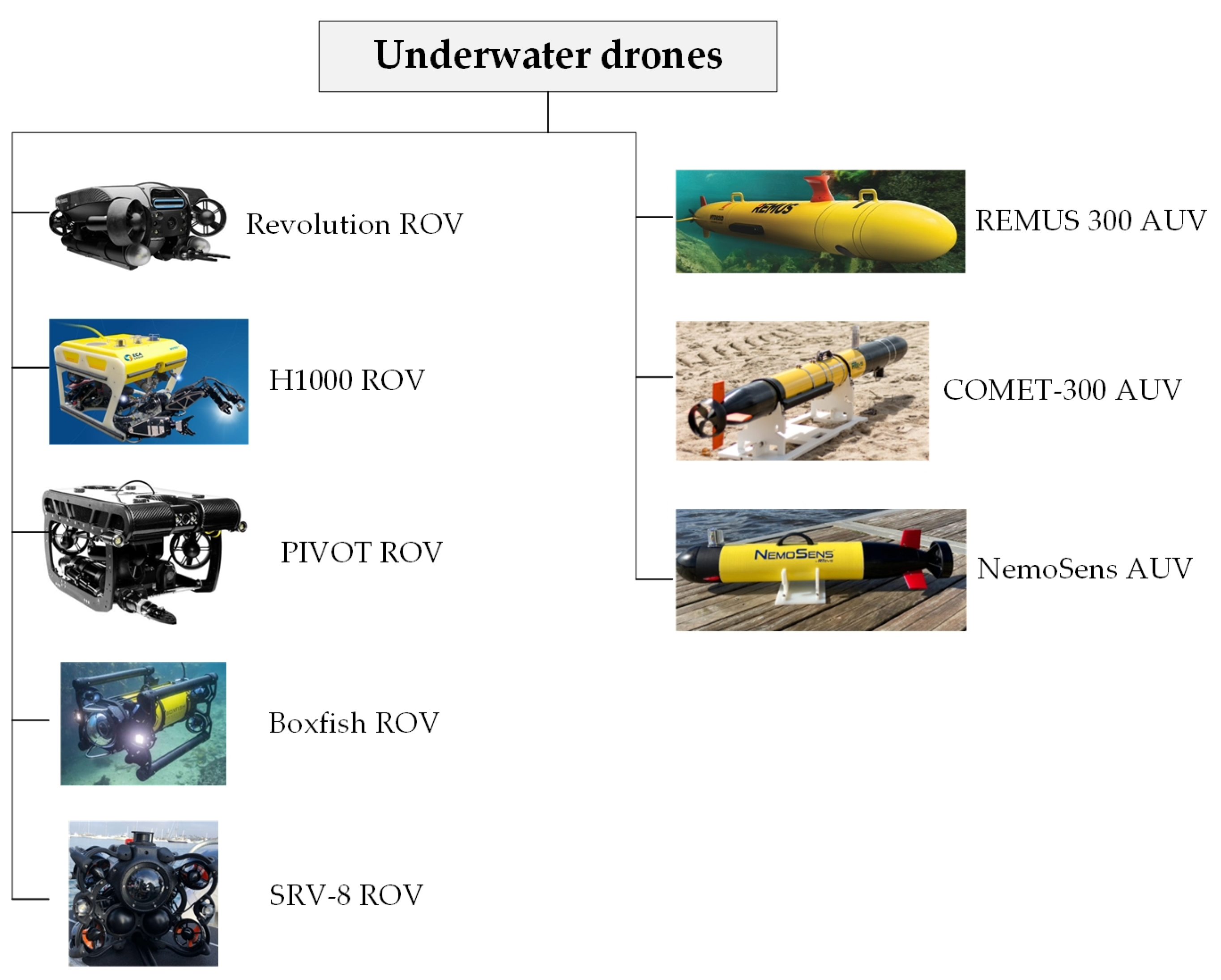

- Revolution Rov Spec Sheet. Available online: https://www.deeptrekker.com/resources/revolution-rov-spec-sheet (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- ECA Hytec H1000. Available online: https://www.rovinnovations.com/eca-hytec-h1000--h2000.html (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- PIVOT 3D Modeling ROV. Available online: https://www.deeptrekker.com/products/underwater-rov/pivot (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Boxfish ROV Features. Available online: https://www.boxfishrobotics.com/products/boxfish-rov/features/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Underwater-SRV-8. Available online: https://wightocean.com/remotely-operated-vehicle (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- REMUS300. Available online: https://www.naval-technology.com/projects/remus-300-unmanned-underwater-vehicle-uuv (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Man Portable AUV COMET-300. Available online: https://rtsys.eu/comet-300-auv (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Micro Auv Nemosens. Available online: https://rtsys.eu/nemosens-micro-auv (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Wang, Z.; Du, J.; Hou, X.; Wang, J.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, X.P.; Ren, Y. Toward communication optimization for future underwater networking: A survey of reinforcement learning-based approaches. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 27, 2765–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savkin, A.V.; Verma, S.C.; Anstee, S. Optimal navigation of an unmanned surface vehicle and an autonomous underwater vehicle collaborating for reliable acoustic communication with collision avoidance. Drones 2022, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.; Goyal, N.; Benslimane, A.; Awasthi, L.K.; Alwadain, A.; Singh, A. Underwater wireless sensor networks: Enabling technologies for node deployment and data collection challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 3500–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjya, K.; De, D. IoUT: Modelling and simulation of edge-drone-based software-defined smart internet of underwater things. Sim. Model. Pract. Theor. 2021, 109, 102304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, M.; Darbra, R.M. Innovations and insights in environmental monitoring and assessment in port areas. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 70, 101472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.H.; Shih, C.F.; Wu, J.J.; Wu, Y.X.; Yang, C.H.; Chang, C.C. ROVs Utilized in communication and remote control integration technologies for smart ocean aquaculture monitoring systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Lv, H.; Fridenfalk, M. Digital twins in the marine industry. Electronics 2023, 12, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Wu, Y.; Qian, L.; Lin, B.; Su, Z. A survey on integrated sensing, communication, and computing networks for smart oceans. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2022, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Lai, M. A review on electromagnetic, acoustic, and new emerging technologies for submarine communication. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 12110–12125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomikos, N.; Gkonis, P.K.; Bithas, P.S.; Trakadas, P. A survey on UAV-aided maritime communications: Deployment considerations, applications, and future challenges. IEEE Open J. Commu. Soc. 2022, 4, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, A.; Alsharif, M.H.; Song, H.K.; Lee, B.M. A survey on underwater wireless power and data transfer system. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 34942–34957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petritoli, E.; Leccese, F. Autonomous underwater glider: A comprehensive review. Drones 2024, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurashi, F.S.; Trichili, A.; Saeed, N.; Ooi, B.S.; Alouini, M.S. Maritime communications: A survey on enabling technologies, opportunities, and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 3525–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, K.; Ahmad, S.; Liaf, A.F.; Karimi, M.; Ahmed, T.; Shawon, M.A.; Mekhilef, S. Oceanic challenges to technological solutions: A review of autonomous underwater vehicle path technologies in biomimicry, control, navigation, and sensing. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 46202–46231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Cui, W.; Chen, C. Review of underwater sensing technologies and applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Wang, J.; Bu, F.; Ruby, R.; Wu, K.; Guo, Z. Recent progress of air/water cross-boundary communications for underwater sensor networks: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 8360–8382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Campagnaro, F.; Ashraf, K.; Rahman, M.R.; Ashok, A.; Guo, H. Communication for underwater sensor networks: A comprehensive summary. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2022, 19, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Mohideen, S.K.; Vedachalam, N. Current status of underwater wireless communication techniques: A review. In Proceedings of the 2022 Second International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Computing, Communication and Sustainable Technologies (ICAECT), Bhilai, India, 21–22 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro, R.J. The past, present, and the future of underwater acoustic signal processing. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 1998, 15, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Celik, A.; Al-Naffouri, T.Y.; Alouini, M.S. Underwater optical wireless communications, networking, and localization: A survey. Ad Hoc Netw. 2019, 94, 101935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haziq, M.; Phung, Q.V.; Lachowicz, S.; Habibi, D.; Ahmad, I. Modulation techniques for underwater acoustic communication: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 150715–150755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Walree, P.A. Propagation and scattering effects in underwater acoustic communication channels. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2013, 38, 614–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

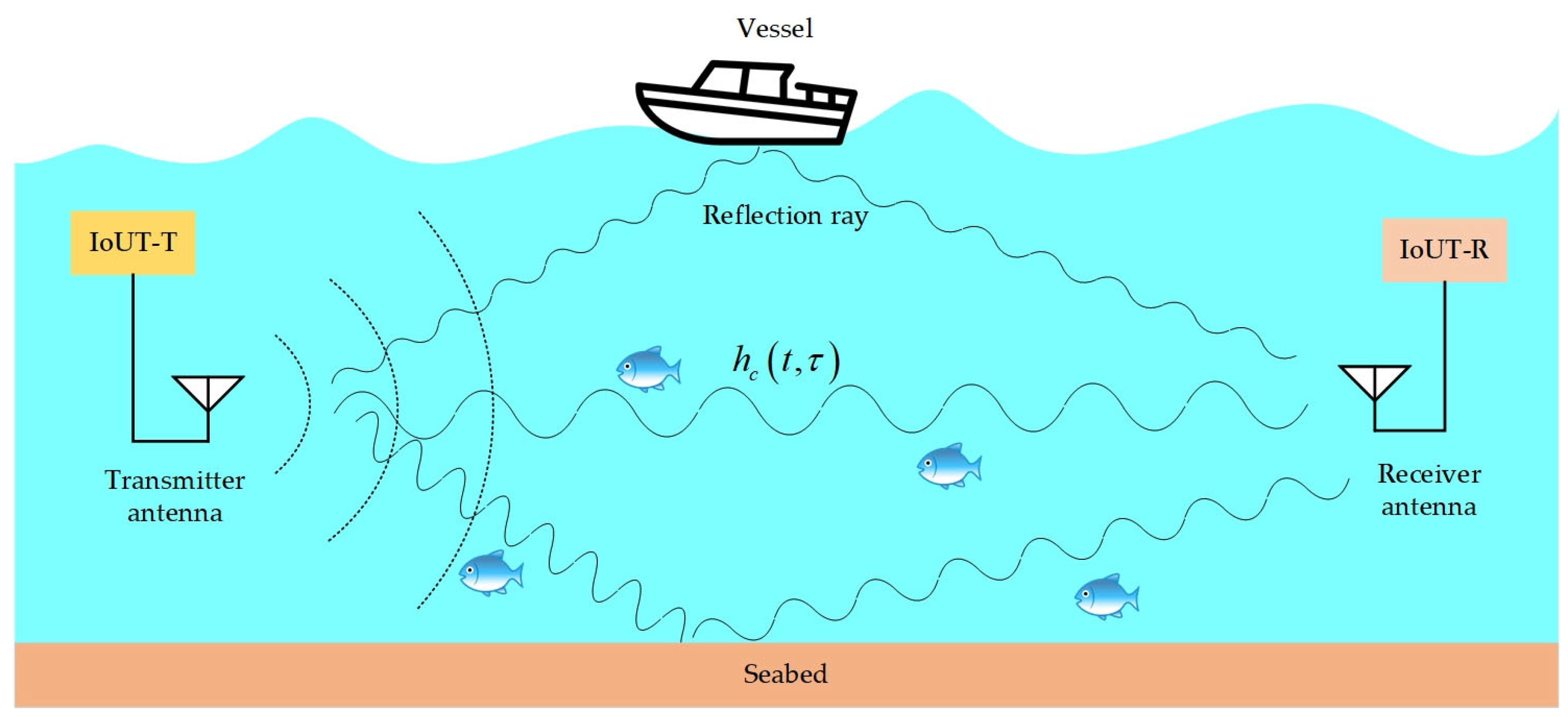

- Stojanovic, M.; Preisig, J. Underwater acoustic communication channels: Propagation models and statistical characterization. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2009, 47, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onasami, O.; Feng, M.; Xu, H.; Haile, M.; Qian, L. Underwater acoustic communication channel modeling using reservoir computing. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 56550–56563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

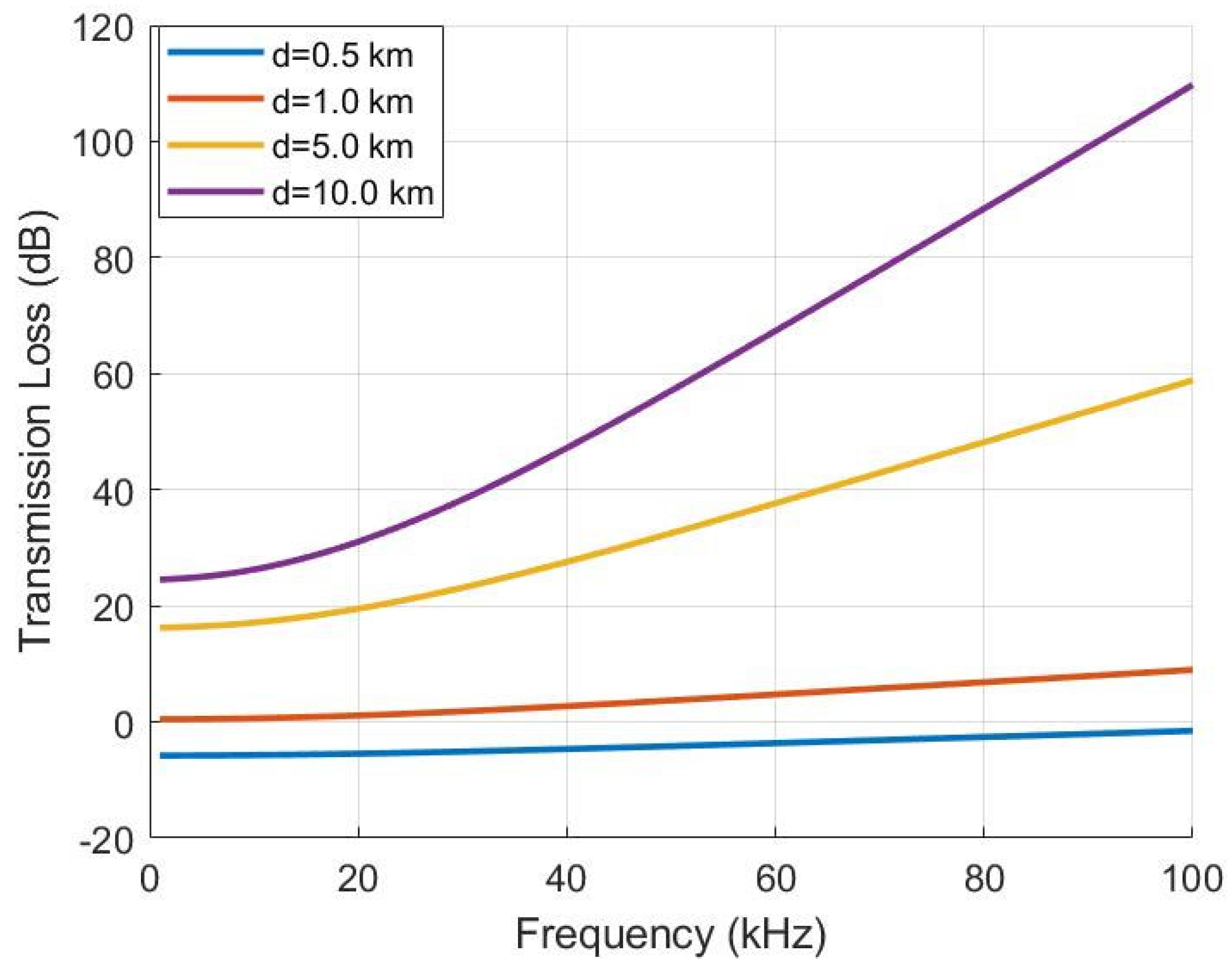

- Duane, D.; Cho, B.; Jain, A.D.; Godø, O.R.; Makris, N.C. The effect of attenuation from fish shoals on long-range, wide-area acoustic sensing in the ocean. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Cai, L.; Shen, X.; Zhao, R. Fundamentals and advancements of topology discovery in underwater acoustic sensor networks: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 21159–21174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Ma, X.; Li, X.; Lu, J. Shot interference detection and mitigation for underwater acoustic communication systems. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2021, 69, 3274–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, R.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Ji, F. Performance analysis of a WPCN-based underwater acoustic communication system. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodovisi, C.; Loreti, P.; Bracciale, L.; Betti, S. Performance analysis of hybrid optical–acoustic AUV swarms for marine monitoring. Future Internet 2018, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Tong, F. Research and implementation on a real-time OSDM MODEM for underwater acoustic communications. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 18434–18448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Han, G.; Wang, J.; Cui, J. End-to-End modulation recognition in underwater acoustic communications using temporal large kernel convolution with gated channel mixer. IEEE Trans. Veh. Tech. 2024, 73, 15076–15086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicacci, F.M.; Mourier, J.; Babatounde, C.; Garcia, J.; Broutta, M.; Gualtieri, J.S.; Aiello, A. A wireless autonomous real-time underwater acoustic positioning system. Sensors 2022, 22, 8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Diamant, R. Adaptive modulation for long-range underwater acoustic communication. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 19, 6844–6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Lv, S.; Wang, C. Cooperative formation control for multiple AUVs with intermittent underwater acoustic communication in IoUT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 15301–15313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, Z.; Guo, H.; Wang, P.; Akyildiz, I.F. Designing acoustic reconfigurable intelligent surface for underwater communications. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 8934–8948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Tong, F. Internet of underwater things infrastructure: A shared underwater acoustic communication layer scheme for real-world underwater acoustic experiments. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electro. Syst. 2023, 59, 6991–7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Kang, C.H.; Kong, M.; Alkhazragi, O.; Guo, Y.; Ouhssain, M.; Weng, Y.; Jones, B.H.; Ng, T.K.; Ooi, B.S. A review on practical considerations and solutions in underwater wireless optical communication. J. Light. Tech. 2020, 38, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Li, Y.; Han, Z. Research on underwater wireless optical communication channel model and Its application. Appl. Sci. 2023, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, H.; Kaddoum, G. Underwater optical wireless communication. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 1518–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Bi, Z.; Liang, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Peng, J. Advancements in underwater optical wireless communication: Channel modeling, PAPR reduction, and simulations with OFDM. IEEE Photonics J. 2024, 16, 6300308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Hanawa, M. Research and Development Trends of Underwater Optical Wireless Communication Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2023 XXXVth General Assembly and Scientific Symposium of the International Union of Radio Science (URSI GASS), Sapporo, Japan, 19–26 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Semernik, I.V.; Demyanenko, A.V.; Samonova, C.V.; Bender, O.V.; Tarasenko, A.A. Modelling of an underwater wireless optical communication channel. In Proceedings of the 2023 Radiation and Scattering of Electromagnetic Waves (RSEMW), Divnomorskoe, Russia, 26–30 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ramley, I.; Alzayed, H.M.; Al-Hadeethi, Y.; Chen, M.; Barasheed, A.Z. An overview of underwater optical wireless communication channel simulations with a focus on the Monte Carlo method. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Combeau, P.; Aveneau, L. New Monte Carlo integration models for underwater wireless optical communication. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 91557–91571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Matsuda, T.; Maki, T. Improving the Quality of Underwater Wireless Optical Communications in Uncertain Ocean Environments. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Underwater Technology (UT), Tokyo, Japan, 6–9 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, Y.; Nordholm, S.; Duncan, A. On the Capacity of Underwater Optical Wireless Communication Systems. In Proceedings of the 2021 fifth Underwater Communications and Networking Conference (UComms), Lerici, Italy, 31 August–2 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.C.; Chen, C.C.; Liaw, S.K.; Afifah, S.; Sung, J.Y.; Yeh, C.H. Performance evaluation of underwater wireless optical communication system by varying the environmental parameters. Photonics 2021, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirripa Spagnolo, G.; Cozzella, L.; Leccese, F. Underwater optical wireless communications: Overview. Sensors 2020, 20, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottilingal, R.K.; Nambath, N. Performance analysis of underwater optical wireless video communication systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Singapore, 19–22 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y. Underwater wireless optical communications: From the lab tank to the real sea. J. Light. Tech. 2025, 43, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.K.; Shao, Y.; Di, Y. Underwater and water-air optical wireless communication. J. Light. Tech. 2022, 40, 1440–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.I.; Okuzawa, H.; Takahashi, S.; Ishibashi, S. Long-distance and High-speed Underwater Optical Wireless Communication System~Challenge to 1Gbps × 100m underwater optical wireless communication. In Proceedings of the 2023 XXXVth General Assembly and Scientific Symposium of the International Union of Radio Science (URSI GASS), Sapporo, Japan, 19–26 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Wang, X.; Bu, F.; Yang, Y.; Ruby, R.; Wu, K. Underwater real-time video transmission via wireless optical channels with swarms of AUVs. IEEE Trans. Veh. Tech. 2023, 72, 14688–14703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Jayakody, D.N.K.; Li, Y. Recent trends in underwater visible light communication (UVLC) systems. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 22169–22225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Yao, H.; Zhao, H.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Y. Coverage enhancement of light-emitting diode array in underwater internet of things over optical channels. Electronics 2023, 12, 4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, P.P.; Venkataraman, H. RF-based wireless communication for shallow water networks: Survey and analysis. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 120, 3415–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, M.C. Magnetic induction for underwater wireless communication networks. IEEE Trans. Antennas Prop. 2012, 60, 2929–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Wells, I.; Dickers, G.; Kear, P.; Gong, X. Re-evaluation of RF electromagnetic communication in underwater sensor networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2010, 48, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shamma’a, A.I.; Shaw, A.; Saman, S. Propagation of electromagnetic waves at MHz frequencies through seawater. IEEE Trans. Antennas Prop. 2004, 52, 2843–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhu, L.; Huang, F.; Hassan, A.; Wang, D.; He, Y. A survey on air-to-sea integrated maritime internet of things: Enabling technologies, applications, and future challenges. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Dou, C.; Wu, Y.; Qian, L.; Lu, R.; Quek, T.Q. Multi-UAV aided multi-access edge computing in marine communication networks: A joint system-welfare and energy-efficient design. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2024, 72, 5517–5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, G.; Bose, P.; Orten, P. 5G cellular communication for maritime applications. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 109451–109472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasaba, R.; Eguchi, K.; Wakisaka, T.; Hirokawa, J.; Hirose, M.; Matsushima, T.; Fukumoto, Y.; Nishida, Y.; Ishii, K. Wavelet OFDM wireless communication system for autonomous underwater vehicles using loop-shaped antennas in underwater environments. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 129633–129645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryecroft, S.; Shaw, A.; Fergus, P.; Kot, P.; Hashim, K. An implementation of a multi-hop underwater wireless sensor network using bowtie antenna. Karbala Inter. J. Mod. Sci. 2021, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouhari, M.; Ibrahimi, K.; Tembine, H.; Ben-Othman, J. Underwater wireless sensor networks: A survey on enabling technologies, localization protocols, and internet of underwater things. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 96879–96899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Díaz, G.; Mena-Rodríguez, P.; Pérez-Álvarez, I.; Jiménez, E.; Dorta-Naranjo, B.P.; Zazo, S.; Perez, M.; Quevedo, E.; Cardona, L.; Hernández, J.J. Underwater electromagnetic sensor networks—Part I: Link characterization. Sensors 2017, 17, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, B.; Naishadham, K. RF Multicarrier Signaling and Antenna Systems for Low SNR Broadband Underwater Communications. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Topical Conference on Power Amplifiers for Wireless and Radio Applications, Austin, TX, USA, 20 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, R.; Wang, W.; Xie, G. An Electrocommunication System using FSK Modulation and Deep Learning based Demodulation for Underwater Robots. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 October 2020–24 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hasaba, R.; Eguchi, K.; Wakisaka, T.; Satoh, H.; Hirokawa, J.; Hirose, M.; Matsushima, T.; Fukumoto, Y.; Nishida, Y.; Ishii, K. Experimental Study of Wavelet-OFDM Radio Communication System for AUVs Under Seawater. In Proceedings of the 2023 17th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Florence, Italy, 26–31 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhilin, I.V.; Bushnaq, O.M.; De Masi, G.; Natalizio, E.; Akyildiz, I.F. A universal multimode (acoustic, magnetic induction, optical, RF) software defined modem architecture for underwater communication. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 9105–9116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Feng, X.; Zhao, T.; Hu, Q. Implementation of underwater electric field communication based on direct sequence spread spectrum (DSSS) and binary phase shift keying (BPSK) modulation. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, D.; Yan, L.; Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Pan, M.; Fang, Y. Dynamic magnetic induction wireless communications for autonomous-underwater-vehicle-assisted underwater IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 9834–9845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Zeng, M.; Mai, J.; Gu, P.; Xu, D. An underwater simultaneous wireless power and data transfer system for AUV with high-rate full-duplex communication. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 38, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S. Network coverage using MI waves for underwater wireless sensor network in shadowing environment. IET Microw. Anten. Prop. 2021, 15, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Sun, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, B. Energy-efficient cooperative MIMO formation for underwater MI-assisted acoustic wireless sensor networks. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Shi, W.; Sun, Y. Performance analysis and design of quasi-cyclic LDPC codes for underwater magnetic induction communications. Phys. Commun. 2023, 56, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, W.; Sun, K.; Fan, D.; Cui, W. Recent progress on underwater wireless communication methods and applications. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Noh, Y.; Lee, U.; Gerla, M. Optical-acoustic hybrid network toward real-time video streaming for mobile underwater sensors. Ad Hoc Netw. 2019, 83, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauni, S.; Manimegalai, C.T.; Krishnan, K.M.; Shreeram, V.; Arvind, V.V.; Srinivas, T.N. Design and analysis of co-operative acoustic and optical hybrid communication for underwater communication. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 117, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.Y.; Ahmad, I.; Habibi, D.; Zahed, M.I.A.; Kamruzzaman, J. Green underwater wireless communications using hybrid optical-acoustic technologies. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 85109–85123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; N’Doye, I.; Ballal, T.; Al-Naffouri, T.Y.; Alouini, M.S.; Laleg-Kirati, T.M. Localization and tracking control using hybrid acoustic–optical communication for autonomous underwater vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 10048–10060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Ruby, R.; Wu, K. Reinforcement learning-based adaptive switching scheme for hybrid optical-acoustic AUV mobile network. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Compu. 2022, 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agheli, P.; Beyranvand, H.; Emadi, M.J. UAV-assisted underwater sensor networks using RF and optical wireless links. J. Light. Tech. 2021, 39, 7070–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Jayakody, D.N.K.; Ribeiro, M.V. A Hybrid UVLC-RF and Optical Cooperative Relay Communication System. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information and Automation for Sustainability, Negambo, Sri Lanka, 11–13 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kodama, T.; Tanaka, K.; Kuwahara, K.; Kariya, A.; Hayashida, S. Depth-adaptive air and underwater invisible light communication system with aerial reflection repeater assistance. Information 2025, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Bohara, V.A.; Srivastava, A. On the optimization of integrated terrestrial-air-underwater architecture using optical wireless communication for future 6G network. IEEE Photonics J. 2022, 14, 7355712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawa, T.; Sato, K.; Watari, K. Remote Control of Underwater Drone by Fiber-Coupled Underwater Optical Wireless Communication. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2022-Chennai, Chennai, India, 21–24 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Yang, L.; da Costa, D.B.; Yu, S. Performance analysis of UAV-based mixed RF-UWOC transmission systems. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2021, 69, 5559–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolboli, J.; Salman, M.; Naik, R.P.; Chung, W.Y. Design and performance evaluation of a relay-assisted hybrid LoRa/optical wireless communication system for IoUT. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2024, 5, 4046–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangsuwan, S.; Jamjareegulgarn, P. Exploring ground reflection effects on received signal strength indicator and path loss in far-field air-to-air for unmanned aerial vehicle-enabled wireless communication. Drones 2024, 8, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, J.P.; Teixeira, F.B.; Campos, R. DURIUS: A Multimodal Underwater Communications Approach for Higher Performance and Lower Energy Consumption. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 9th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Aveiro, Portugal, 12–27 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Q.; Bose, N.; Hwang, J.; Zou, T. Exploring the potential of autonomous underwater vehicles for microplastic detection in marine environments: A systematic review. Drones 2025, 9, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Sánchez, G.; Markfort, G.; Berghald, M.; Ritzenhofen, L.; Schernewski, G. Aerial and underwater drones for marine litter monitoring in shallow coastal waters: Factors influencing item detection and cost-efficiency. Environ. Monitor. Assess. 2022, 194, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, R.L.P.; Boogaard, F.C.; de Graaf-van Dinther, R.E. Innovative water quality and ecology monitoring using underwater unmanned vehicles: Field applications, challenges and feedback from water managers. Water 2020, 12, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.; Shih, P.Y.; Chen, L.P.; Wang, C.C.; Samani, H. Towards underwater sustainability using ROV equipped with deep learning system. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Automatic Control Conference (CACS), Hsinchu, Taiwan, 4–7 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xi, D.; Shao, X.; Tabeta, S.; Mizuno, K. Riverbed litter monitoring using consumer-grade aerial-aquatic speedy scanner (AASS) and deep learning based super-resolution reconstruction and detection network. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209, 117030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslin, M.; Louis, S.; Godary Dejean, K.; Lapierre, L.; Villéger, S.; Claverie, T. Underwater robots provide similar fish biodiversity assessments as divers on coral reefs. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conser. 2021, 7, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, G.H.S.; Araújo, F.G. Underwater drones reveal different fish community structures on the steep slopes of a tropical reservoir. Hydrobiologia 2022, 849, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalmpanti, M.; Pardalou, A.; Tsikliras, A.C.; Dimarchopoulou, D. Assessing fish communities in a multiple-use marine protected area using an underwater drone (Aegean Sea, Greece). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2021, 101, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomo, A.B.; Barreto, J.; Teixeira, J.B.; Oliveira, L.; Cajaíba, L.; Joyeux, J.C.; Barcelos, N.; Martins, A.S. Using drones and ROV to assess the vulnerability of marine megafauna to the Fundão tailings dam collapse. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazzolla, D.; Bonamano, S.; Penna, M.; Resnati, A.; Scanu, S.; Madonia, N.; Fersini, G.; Coppini, G.; Marcelli, M.; Piermattei, V. Combining USV ROV and multimetric indices to assess benthic habitat quality in coastal areas. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Ye, Q.; Lai, C.; Kou, G. Cryptography-based secure underwater acoustic communication for UUVs: A Review. Electronics 2025, 14, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, W.; Semkin, V.; Ratyal, N.I.; Yaqoob, Q.; Gul, J.; Guvenc, I. Threats from and countermeasures for unmanned aerial and underwater vehicles. Sensors 2022, 22, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotis, K.; Stavrinos, S.; Kalloniatis, C. Review on semantic modeling and simulation of cybersecurity and interoperability on the Internet of Underwater Things. Future Internet 2022, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Qi, X.; Zhang, W.; Qiao, G.; Zuo, D. A lightweight secure scheme for underwater wireless acoustic network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, N.; Ali, M.; Naeem, F.; Ghazy, A.S.; Kaddoum, G. State-of-the-art security schemes for the Internet of Underwater Things: A holistic survey. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2024, 5, 6561–6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junejo, N.U.R.; Sattar, M.; Adnan, S.; Sun, H.; Adam, A.B.; Hassan, A.; Esmaiel, H. A survey on physical layer techniques and challenges in underwater communication systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, H.H.; Wang, L. Physical layer security for next generation wireless networks: Theories, technologies, and challenges. IEEE Commun. Sur. Tutor. 2016, 19, 347–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, Z.A.; Leftah, H.A.; Sun, H.; Qi, J.; Wang, J.; Esmaiel, H. Deep learning-based code indexed modulation for autonomous underwater vehicles systems. Veh. Commun. 2021, 28, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Zhang, M.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y. Research on time–frequency joint equalization algorithm for underwater acoustic FBMC/OQAM systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S. State-of-the-art medium access control (MAC) protocols for underwater acoustic networks: A survey based on a MAC reference model. IEEE Commun. Sur. Tutor. 2017, 20, 96–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukis, G.; Safouri, K.; Tsaoussidis, V. All about delay-tolerant networking (DTN) contributions to future internet. Future Internet 2024, 16, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Ullah, I.; Liu, X.; Choi, D. A review of underwater localization techniques, algorithms, and challenges. J. Sens. 2020, 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Miller, B.; Miller, G. Navigation of underwater drones and integration of acoustic sensing with onboard inertial navigation system. Drones 2021, 5, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, R.; Khan, F.H.; Amir, M.; Otero, P.; Poncela, J. Critical analysis of localization and time synchronization algorithms in underwater wireless sensor networks: Issues and challenges. Wirel. Pers. Communi. 2021, 116, 1231–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhubaev, Y.; Belyaev, V.; Murashov, Y.; Prokofev, O. Controlling of unmanned underwater vehicles using the dynamic planning of symmetric trajectory based on machine learning for marine resources exploration. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eimeni, S.N.H.; Khosravi, A. An online energy management system based on minimum-time speed planning for autonomous underwater vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intel. Veh. 2025, 10, 3600–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Imran, M.; Alharbi, A.; Mohamed, E.M.; Fouda, M.M. Energy harvesting in underwater acoustic wireless sensor networks: Design, taxonomy, applications, challenges and future directions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 134606–134622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Xu, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. Energy-optimized path planning and tracking control method for AUV based on SOC state estimation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Si, Y.; Chen, Y. A review of subsea AUV technology. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadali, L.; Hossain, A.; Billa, N.K.; Mummaneni, K. AI-powered cognitive modulation adaptation for energy-efficient underwater acoustic communication. Intell. Mar. Tech. Syst. 2025, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimos, A.; Skoutas, D.N.; Nomikos, N.; Skianis, C. A survey on UxV swarms and the role of artificial intelligence as a technological enabler. Drones 2025, 9, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popli, M.S.; Singh, R.P.; Popli, N.K.; Mamun, M. A federated learning framework for enhanced data security and cyber intrusion detection in distributed network of underwater drones. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 12634–12646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, A.; Piran, M.J.; Song, H.K.; Lee, B.M. A survey on unmanned underwater vehicles: Challenges, enabling technologies, and future research directions. Sensors 2023, 23, 7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Feng, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.X.; Ge, N.; Lu, J. Hybrid satellite-terrestrial communication networks for the maritime Internet of Things: Key technologies, opportunities, and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 8910–8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Hildre, H.P.; Zhang, H. A systematic survey of digital twin applications: Transferring knowledge from automotive and aviation to maritime industry. IEEE Trans. Intel. Transport. Syst. 2025, 26, 4240–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanov, A.; Kramar, V. Marine internet of things platforms for interoperability of marine robotic agents: An overview of concepts and architectures. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Michaelides, M.P.; Herodotou, H. Internet of ships: A survey on architectures, emerging applications, and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 9714–9727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbakht, M.; Xiang, W.; Hanzo, L.; Azghadi, M.R. Internet of underwater things and big marine data analytics–A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 904–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Huang, C.; Li, X.; Lin, B.; Shu, M.; Wang, J.; Pan, M. Power-efficient data collection scheme for AUV-assisted magnetic induction and acoustic hybrid Internet of Underwater Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 11675–11684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Mazinani, A.; Othman, N.Q.H.; Amjad, H. Towards the internet of underwater things: A comprehensive survey. Earth Sci. Inform. 2022, 15, 735–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicioğlu, M.; Calhan, A. Performance analysis of cross-layer design for internet of underwater things. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 15429–15434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Li, Y.; Sadiq, M.; Liang, J.; Khan, M.A. Recent advances, future trends, applications and challenges of internet of underwater things (IoUT): A comprehensive review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkenyereye, L.; Nkenyereye, L.; Ndibanje, B. Internet of underwater things: A survey on simulation tools and 5G-based underwater networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.S.; Saeed, R.A.; Eltahir, I.K.; Khalifa, O.O. A systematic review on energy efficiency in the internet of underwater things (IoUT): Recent approaches and research gaps. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2023, 213, 103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Wang, J.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Song, S.; Zhang, X.; Ren, Y. Machine-learning-aided mission-critical Internet of Underwater Things. IEEE Netw. 2021, 35, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delladetsimas, A.P.; Papangelou, S.; Iosif, E.; Giaglis, G. Integrating blockchains with the IoT: A review of architectures and marine use cases. Computers 2024, 13, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Mohsan, S.A.H.; Li, Y.; Alsharif, M.H. Architectural framework for underwater IoT: Forecasting system for analyzing oceanographic data and observing the environment. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consul, P.; Budhiraja, I.; Garg, D. Deep reinforcement learning based reliable data transmission scheme for internet of underwater things in 5G and beyond networks. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 235, 1752–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.A.; Khan, M.T.R.; Saad, M.M.; Islam, M.M.; Kim, D. AI-enabled reliable delay sensitive communication mechanism in IoUT using CoAP. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 18832–18841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, O.; Zeadally, S. Internet of underwater things communication: Architecture, technologies, research challenges and future opportunities. Ad Hoc Netw. 2022, 135, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Kishk, M.A.; Alouini, M.S. Coverage enhancement of underwater Internet of Things using multilevel acoustic communication networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 25373–25385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.; de Gea Fernández, J.; Hildebrandt, M.; Koch, C.E.S.; Wehbe, B. Recent advances in ai for navigation and control of underwater robots. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2022, 3, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobana, M.; Madhavan, M.; Nandhini, S.; Neeraj, D. Ai-underwater drone in protection of waterways by relating design thinking framework. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), Coimbatore, India, 23–25 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, A.; Ghosh, A.R. AI-driven surveillance of the health and disease status of ocean organisms: A review. Aquac. Inter. 2024, 32, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er, M.J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W. Research challenges, recent advances, and popular datasets in deep learning-based underwater marine object detection: A review. Sensors 2023, 23, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshibli, A.; Memon, Q. Benchmarking YOLO models for marine search and rescue in variable weather conditions. Automation 2025, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Galluccio, L.; Morabito, G. AI-driven adaptive communications for energy-efficient underwater acoustic sensor networks. Sensors 2025, 25, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Luo, K.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, A. An advanced AI-based lightweight two-stage underwater structural damage detection model. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.J.; Yun, C.; Lee, S.J.; Park, K.R. Artificial intelligence-based low-light marine image enhancement for semantic segmentation in edge intelligence empowered internet of things environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 4086–4114. [Google Scholar]

- Kotian, A.L.; Sheik, A. Efficient AI Models for Extreme Edge Environments: A Comprehensive Review for Space, Underwater, and Disaster Zones. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), Coimbatore, India, 25–27 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G.; Kamaruddin, M.H.; Kang, H.S.; Goh, P.S.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, K.Q.; Ng, C.Y. Watertight integrity of underwater robotic vehicles by self-healing mechanism. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 1995–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lan, Y.; Cui, Z.; Cai, J.; Zhang, W. A survey on federated learning: Challenges and applications. Inter. J. Mach. Learn. Cyber. 2023, 14, 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adetunji, F.O.; Ellis, N.; Koskinopoulou, M.; Carlucho, I.; Petillot, Y.R. Digital twins below the surface: Enhancing underwater teleoperation. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2024, Singapore, 15–18 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liang, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Digital twin-driven industrialization development of underwater gliders. IEEE Trans. Indus. Infor. 2023, 19, 9680–9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambertini, A.; Menghini, M.; Cimini, J.; Odetti, A.; Bruzzone, G.; Bibuli, M.; Mandanici, E.; Vittuari, L.; Castaldi, P.; Caccia, M.; et al. Underwater drone architecture for marine digital twin: Lessons learned from sushi drop project. Sensors 2022, 22, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yan, L.; Li, X.; Han, S. System-level digital twin modeling for underwater wireless IoT networks. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madusanka, N.S.; Fan, Y.; Yang, S.; Xiang, X. Digital twin in the maritime domain: A review and emerging trends. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, F.; Chen, Z. Virtual-reality-based online simulator design with a virtual simulation system for the docking of unmanned underwater vehicle. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 112780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korniejenko, K.; Kontny, B. The usage of virtual and augmented reality in underwater archeology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, O.; Aly, A.; Jones, R.; Varga, M.; Bazazian, D. Beyond the surface: A scoping review of vision-based underwater experience technologies and user studies. Intel. Mar. Tech. Syst. 2024, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Bai, Y. Unlocking the ocean 6G: A review of path-planning techniques for maritime data harvesting assisted by autonomous marine vehicles. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, N.; Kato, N. A survey on space-air-ground-sea integrated network security in 6G. IEEE Commun. Sur. Tutor. 2021, 24, 53–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Main Contributions | IoUT | AI | VR | DT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] |

| √ | √ | × | × |

| [26] |

| √ | √ | × | × |

| [27] |

| √ | × | × | × |

| [28] |

| √ | √ | × | × |

| [29] |

| √ | × | × | × |

| [30] |

| √ | × | × | √ |

| [31] |

| × | × | × | √ |

| [32] |

| √ | × | √ | × |

| [33] |

| √ | √ | × | × |

| [34] |

| √ | × | × | × |

| [35] |

| √ | × | × | × |

| [36] |

| √ | × | × | × |

| [19] |

| × | √ | × | × |

| This work |

| √ | √ | √ | √ |

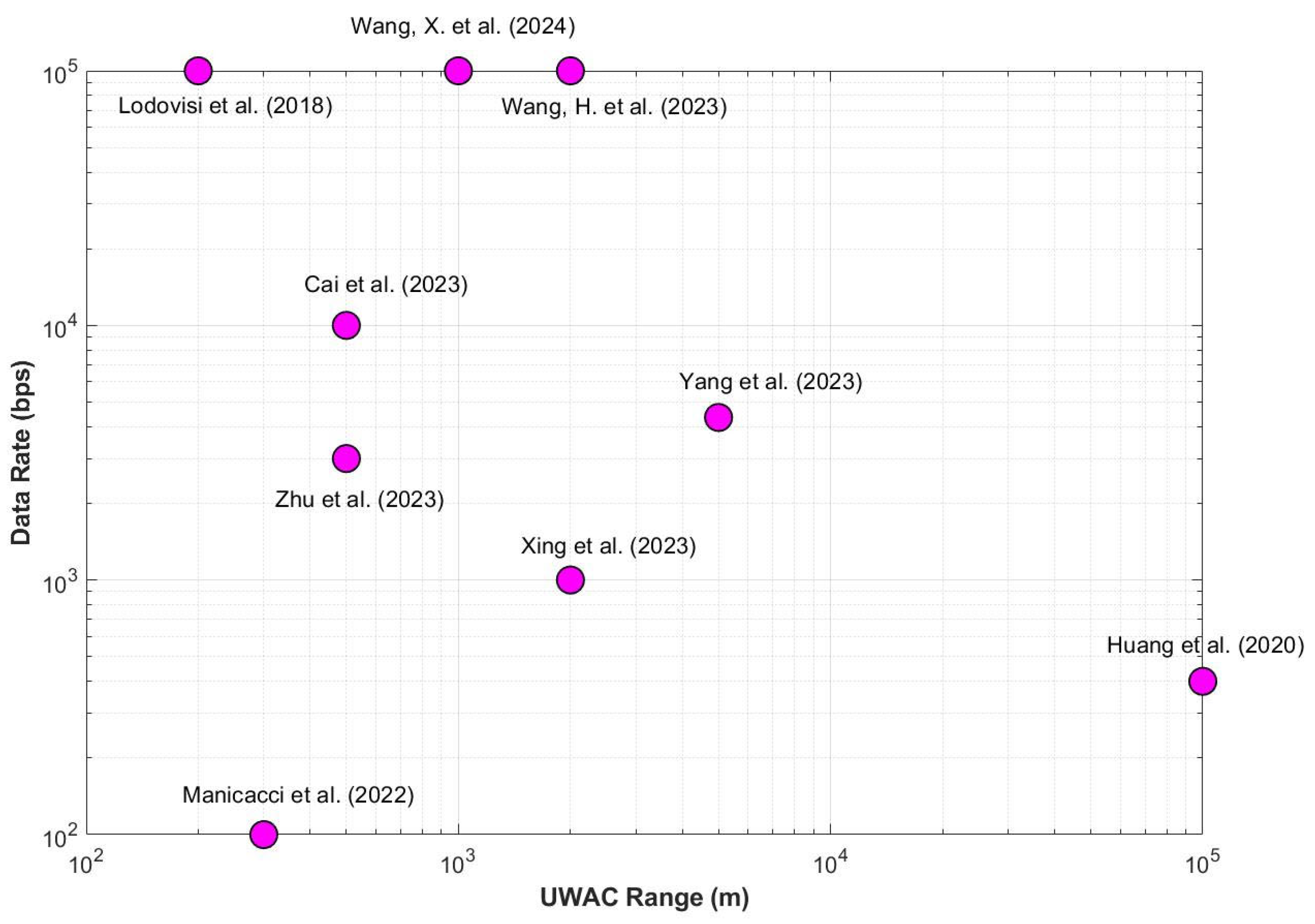

| Reference | Range | Data Rate | Complexity | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xing et al. [46] | 2–3 km | 1 kbps | Medium | WPCN-UWAC enabling energy harvesting for IoUT |

| Lodovisi et al. [47] | 200 m | 100 kbps | High | A hybrid optical–acoustic system achieving Mbps throughput in clear waters |

| Yang et al. [48] | 5 km | 4.35 kbps | Medium | OSDM modem robust to multipath and Dropper |

| Wang, X. et al. [49] | 1 km | 100 kbps | Medium | Deep learning–based adaptive modulation classification (GIQNet AMC) |

| Manicacci et al. [50] | 300 m | 100 bps | Low | Real-time acoustic positioning system with buoy relays |

| Huang et al. [51] | 100–700 km | 37–400 bps | High | Adaptive modulation for ultra-long-range UWAC |

| Cai et al. [52] | 100–500 m | 10 kbps | Medium | AUV formation networking under intermittent acoustic links |

| Wang, H. et al. [53] | 0.5–2 km | 100 kbps | Medium | RIS-assisted acoustic comms are improving reliability and rate |

| Zhu et al. [54] | 500 m | 2–3 kbps | Medium | Shared IoUT acoustic layer with testbed validation |

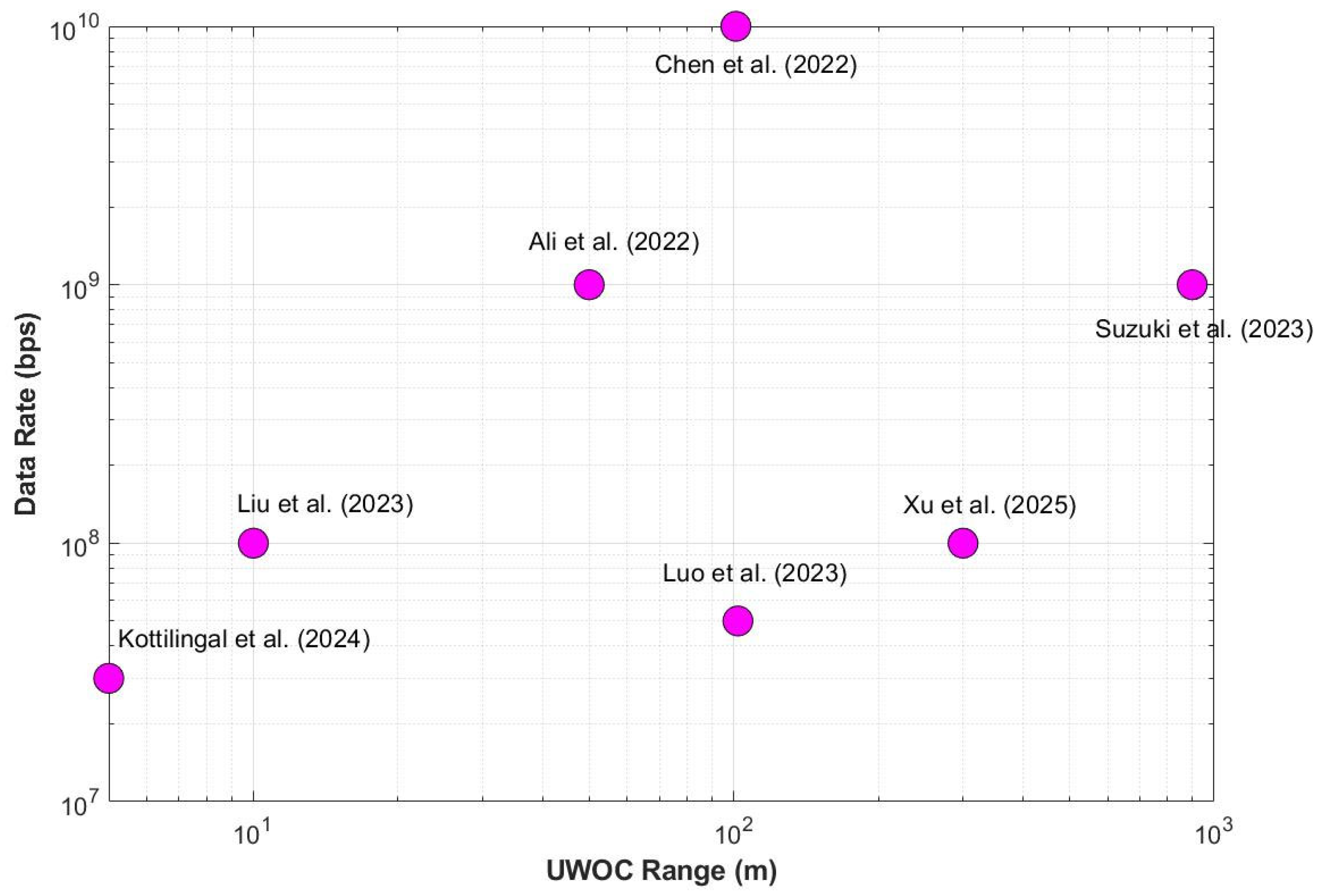

| Reference | Range | Data Rate | Complexity | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kottilingal et al. [67] | 1–5 m | 2–30 Mbps | Medium | Proposed real-time duplex video transmission using multiple wavelengths |

| Xu et al. [68] | 100–300 m | 100 Mbps | High | Demonstrated multi-hop UWOC feasibility with field validations |

| Chen et al. [69] | 100 m | 10 Gbps | High | Proposed a hybrid UWOC, enabling seamless IoUT |

| Suzuki et al. [70] | 100–900 m | 1 Gbps | High | Proposed multi-beam transmitters and multi-PMT receivers, proving high-speed robustness |

| Luo et al. [71] | 10–100 m | 50 Mbps | Medium | Proposed AUV swarm-based UWOC relaying with adaptive beam/power control for scalable IoUT |

| Ali et al. [72] | 50 m | 100 Mbps–1 Gbps | Medium | Proposed UVLC trends and optimizing energy-efficient protocols and 5G/6G for IoUT network |

| Liu et al. [73] | 10 m | 100 Mbps | Medium | Developed a lemniscate-shaped LED array, improving BER and uniformity; simulation and validation for robust UWOC links |

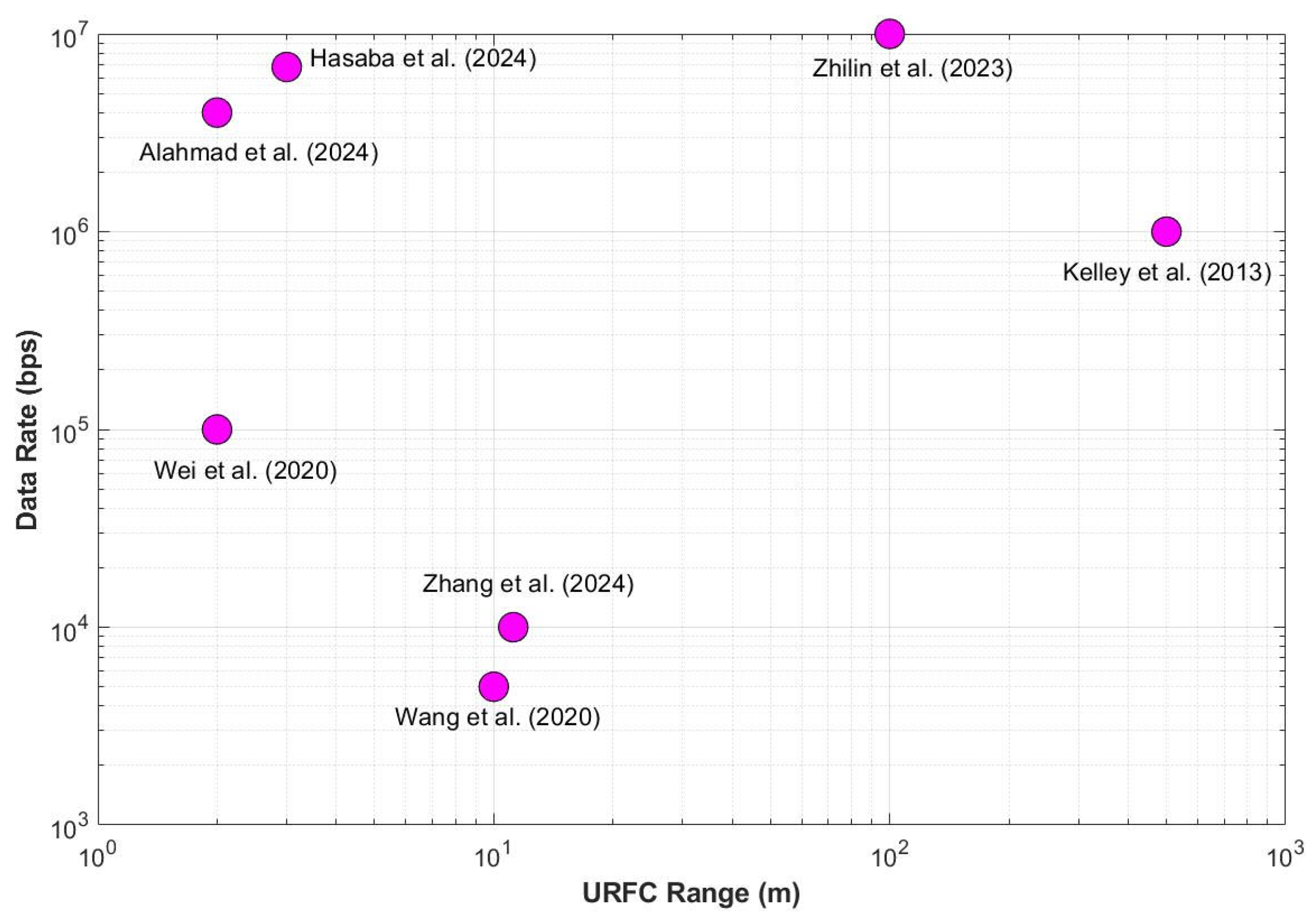

| Reference | Range | Data Rate | Complexity | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alahmad et al. [5] | 2 m | 4 Mbps | Medium | Real-time video with AUVs |

| Hasaba et al. [81] | 2–3 m | 6.8 Mbps | High | Developed Wavelet-OFDM with loop antennas, providing robust short-range RF links for AUVs |

| Kelley et al. [85] | 100–1000 m | 1 Mbps | Medium | Proposed RF signaling with LDPC framework for medium-range RF UWAC |

| Wang et al. [86] | 10 m | 5 kbps | Medium | Proposed BPSK and deep learning demodulation, achieving BER with low power |

| Zhilin et al. [88] | 100 m | 10 Mbps | High | Designed a universal multimode SDR modem (UniSDR) for IoUT, enabling adaptive, hybrid underwater networking |

| Zhang et al. [89] | 11.2 m | 10 kbps | Medium | Proposed DSSS-BPSK communication system, compact and interference-resistant for underwater robots |

| Wei et al. [90] | 2 m | 100 kbps | High | Developed a dynamic MI channel model, ensuring stable, power-efficient AUV-assisted IoUT links |

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

| Challenges |

|

| Limitations |

|

| Opportunities |

|

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

| Challenges |

|

| Limitations |

|

| Opportunities |

|

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

| Challenges |

|

| Limitations |

|

| Opportunities |

|

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

| Challenges |

|

| Limitations |

|

| Opportunities |

|

| Reference | Modality | Main Application | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Han et al. [96] | UWAC–UWOC |

|

|

| Gauni et al. [97] | UWAC–UWOC |

|

|

| Islam et al. [98] | UWAC–UWOC |

|

|

| Zhang et al. [99] | UWAC–UWOC |

|

|

| Luo et al. [100] | UWAC–UWOC |

|

|

| Agheli et al. [101] | UWOC-RF |

|

|

| Ali et al. [102] | UWOC-RF |

|

|

| Kodama et al. [103] | UWOC-RF |

|

|

| Li et al. [106] | UWOC-RF |

|

|

| Bolboli et al. [107] | UWOC-RF |

|

|

| Zhilin et al. [88] | Multimodal |

|

|

| Loureiro et al. [109] | Multimodal |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duangsuwan, S.; Klubsuwan, K. Underwater Drone-Enabled Wireless Communication Systems for Smart Marine Communications: A Study of Enabling Technologies, Opportunities, and Challenges. Drones 2025, 9, 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110784

Duangsuwan S, Klubsuwan K. Underwater Drone-Enabled Wireless Communication Systems for Smart Marine Communications: A Study of Enabling Technologies, Opportunities, and Challenges. Drones. 2025; 9(11):784. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110784

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuangsuwan, Sarun, and Katanyoo Klubsuwan. 2025. "Underwater Drone-Enabled Wireless Communication Systems for Smart Marine Communications: A Study of Enabling Technologies, Opportunities, and Challenges" Drones 9, no. 11: 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110784

APA StyleDuangsuwan, S., & Klubsuwan, K. (2025). Underwater Drone-Enabled Wireless Communication Systems for Smart Marine Communications: A Study of Enabling Technologies, Opportunities, and Challenges. Drones, 9(11), 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110784