MCB-RT-DETR: A Real-Time Vessel Detection Method for UAV Maritime Operations

Highlights

- MCB-RT-DETR achieves 82.9% mAP@0.5 and 49.7% mAP@0.5:0.95 on the SeaDronesSee dataset, surpassing the baseline RT-DETR by 4.5% and 3.4%, respectively.

- The method maintains real-time inference speed of 50 FPS while significantly improving detection accuracy under complex maritime conditions (e.g., wave interference, scale variations, and small targets).

- Presents a resilient visual perception framework to support autonomous UAV maritime operations, enabling reliable ship detection in challenging environments.

- Demonstrates strong generalization across diverse datasets (DIOR and VisDrone2019), indicating broad applicability to aerial and remote sensing scenarios.

Abstract

1. Introduction

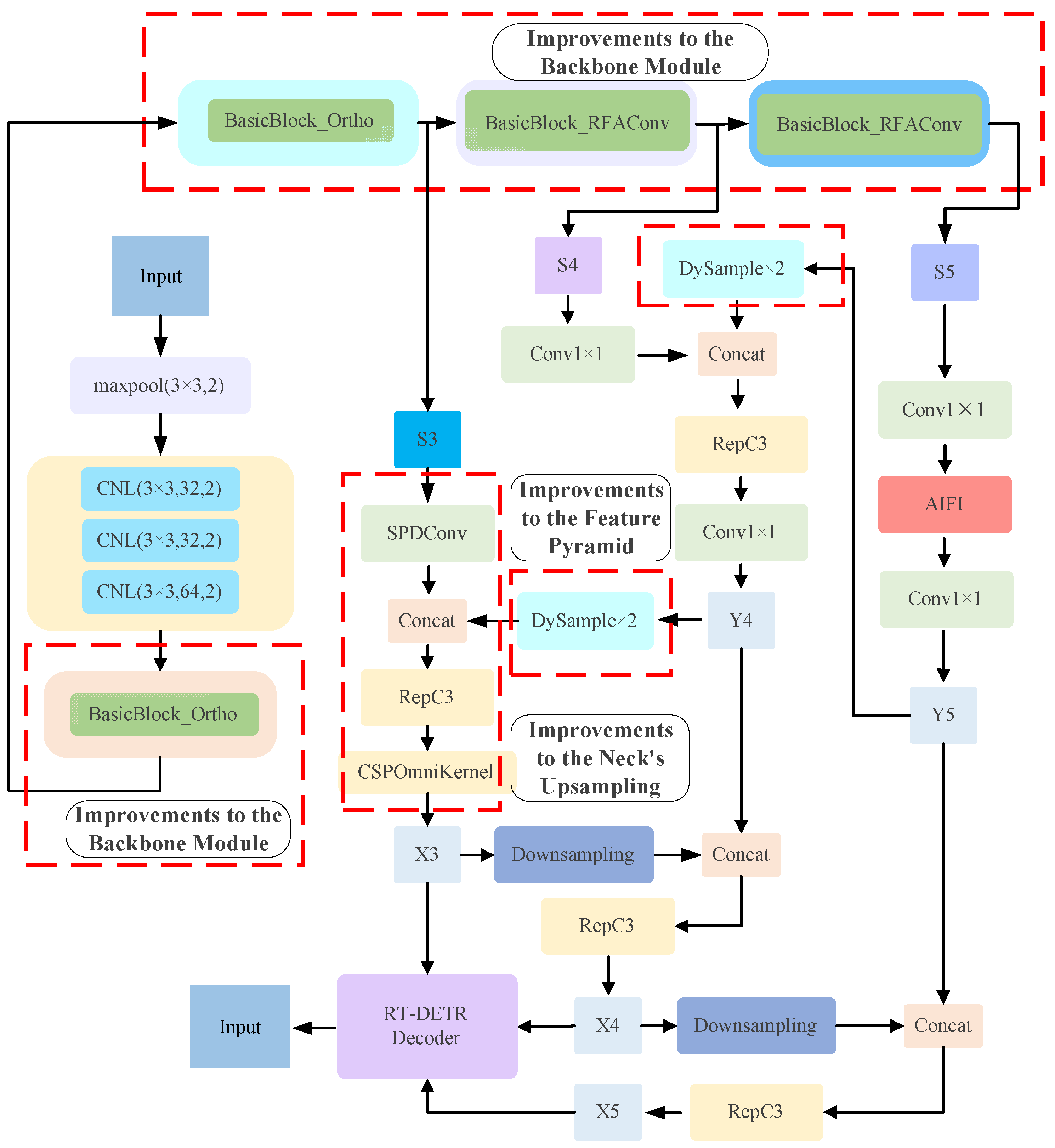

- (1)

- A multi-module collaborative enhancement framework for RT-DETR is proposed. Specifically, an Orthogonal Channel Attention mechanism (Ortho) is introduced into the shallow layers of the backbone network. This preserves high-frequency details of ship edges. It also enhances feature discriminative power. In the deep layers, standard convolution is replaced with Receptive Field Attention Convolution (RFAConv). This allows convolution kernel parameters to adapt based on local content. It significantly enhances robustness to background clutter.

- (2)

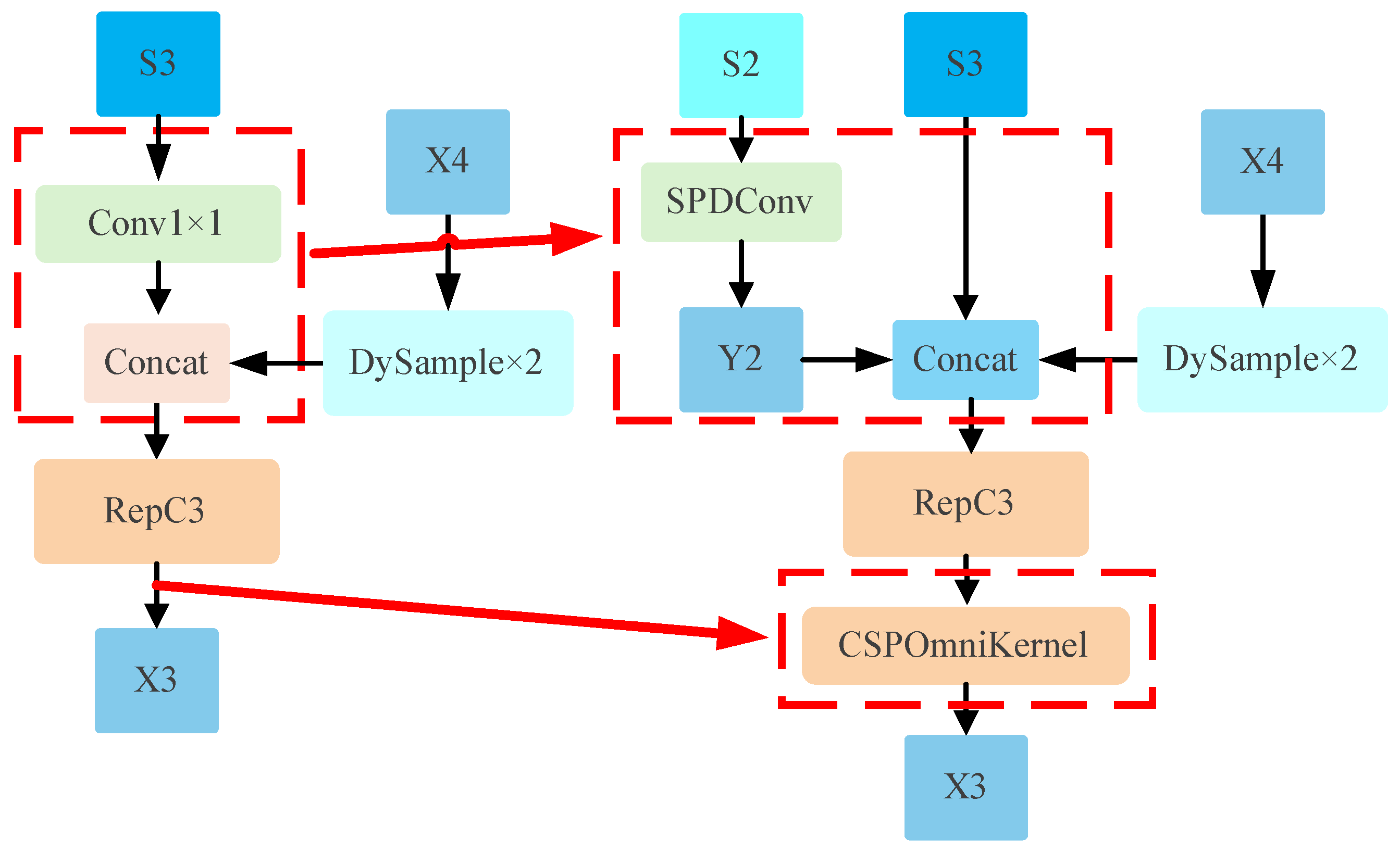

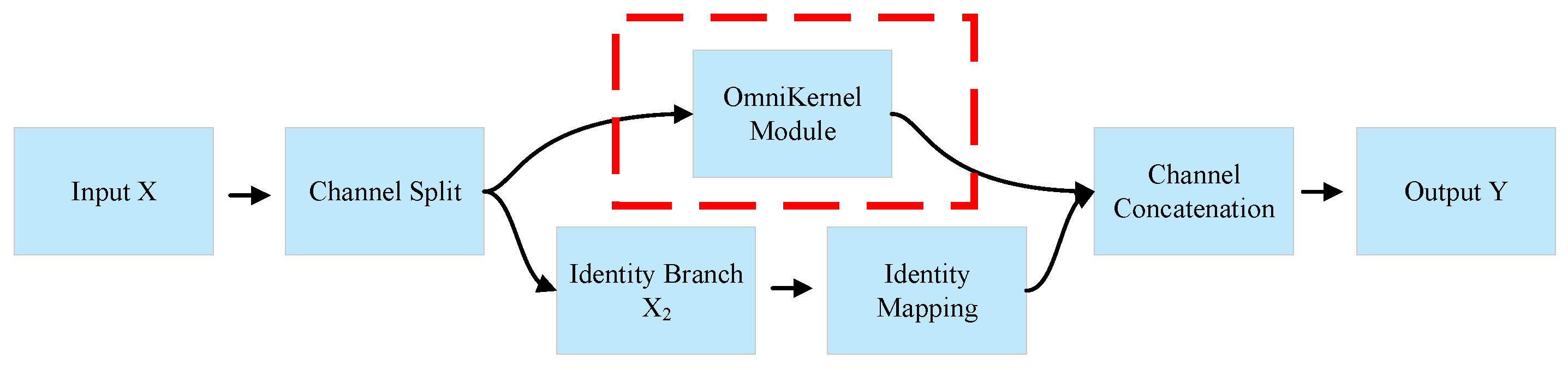

- A Small Object Detail Enhancement Pyramid Network (SOD-EPN) is designed. This neck module integrates Spatial-to-Depth convolution (SPDConv). SPDConv compresses high-resolution feature maps without losing detail. It also includes a novel CSP-OmniKernel module. This module strengthens feature fusion by employing multi-scale kernel transformation combined with attention. Its goal is to significantly improve detection capability for small ship targets.

- (3)

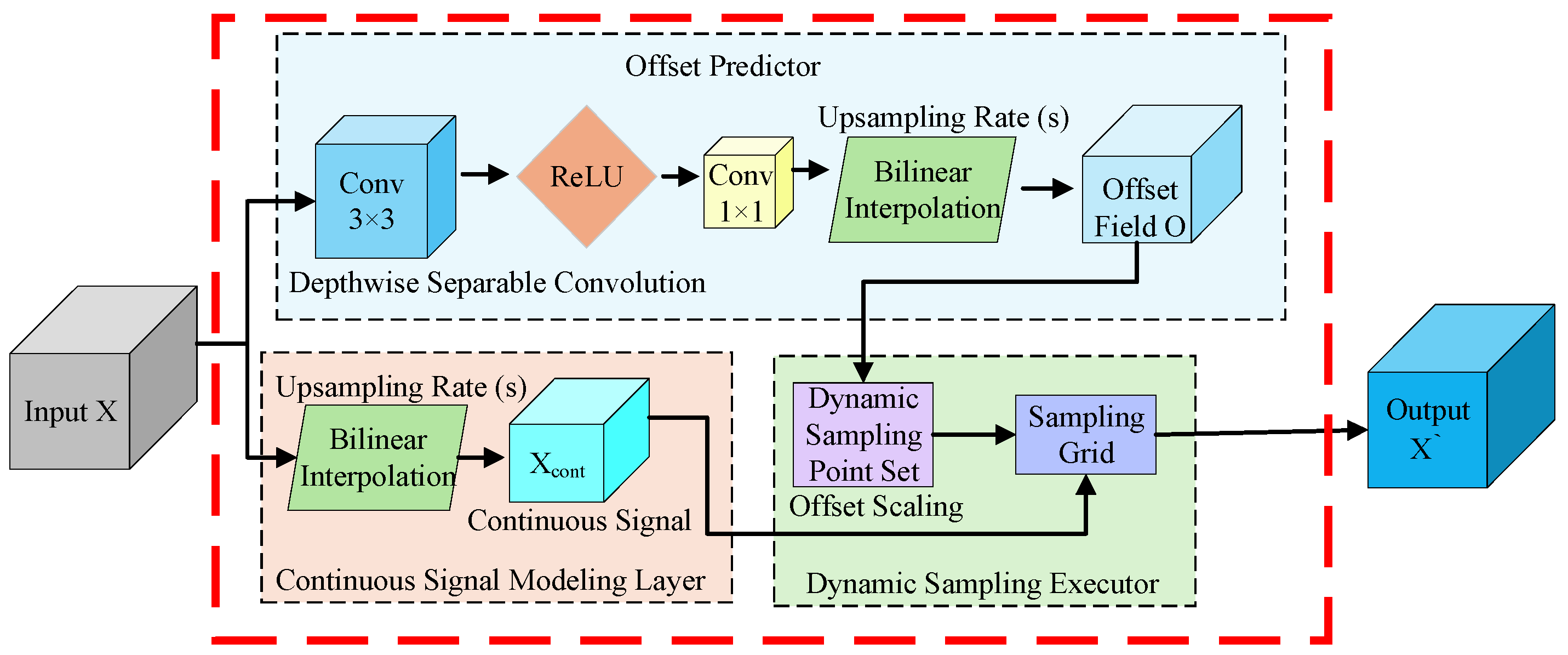

- An ultra-lightweight Dynamic Upsampler (DySample) is introduced into the neck network. This module replaces traditional interpolation methods. It generates content-aware sampling points. This enables more precise feature map reconstruction. Consequently, it improves localization accuracy for ships of different scales. Its design ensures minimal computational overhead.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Object Detection Methods and Their Limitations

- (1)

- Limited Feature Representation: Handcrafted features (e.g., HOG, SIFT) possess weak representational power for targets. They struggle to capture the diverse appearance of ships under varying illumination, viewing angles, and scales. This results in poor generalization capability.

- (2)

- Low Computational Efficiency: The sliding window mechanism generates massive redundant computations. Detection speeds are slow. They fail to meet real-time requirements.

- (3)

- Insufficient Environmental Robustness: Suppression capability against complex background interference is weak. This interference includes sea waves, cloud shadows, and fog. Consequently, false positives and missed detections occur frequently.

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Object Detection Methods

2.2.1. Two-Stage Detectors

2.2.2. Single-Stage Detectors

2.3. Application of Transformers in Object Detection

2.4. Specialized Research on Maritime Object Detection

- (1)

- YOLO-based Improved Methods: Li et al. [29] proposed GGT-YOLO. It integrates Transformer modules to enhance small-object detection capability. It also employs GhostNet to reduce computational costs. This model is specifically designed for UAV maritime patrols, achieving 6.2 M parameters and 15.1 G FLOPs. Li et al. [30] introduced oriented bounding boxes, the CK_DCNv4 module for enhanced geometric feature extraction, and the SGKLD loss function for elongated targets. This led to a notable enhancement in both the precision and resilience of detection systems operating within intricate maritime environments.

- (2)

- Generalization Capability for Complex Scenes: Cheng et al. [31] proposed YOLO-World, which explores open-vocabulary object detection to enhance adaptability to unknown and complex scenes. On the LVIS dataset, it achieves 52.0 FPS. Chen et al. [32] designed a novel feature pyramid network specifically for complex maritime environments. It suppresses complex background features during detection and highlights features of small targets. This achieves more efficient small object detection performance.

- (3)

- Lightweight Deployment: Tang et al. [33] focused on the limited computing resources of UAVs. They designed a channel pruning strategy based on YOLOv8s. This achieved lightweight model deployment, with their method achieving 7.93 M parameters, 28.7 GFLOPs, and 227.3 FPS on the SeaDronesSee dataset. It reflects the urgent need for efficiency in practical applications.

- (4)

- Recent Advances of Transformers in Maritime Detection: In recent years, researchers have begun to explore the application of Transformer architectures in maritime detection. Xing et al. [34] proposed the S-DETR model, which enhances the detection performance for multi-scale ships at sea through a scale attention module and a dense query decoder design. However, its model parameter count remains high, and its real-time performance—with an FPS of only 27.98 on the Singapore Maritime Dataset (SMD)—and robustness in occluded scenarios still need improvement. Wang et al. [35] proposed Ship-DETR, a model designed to enhance the recognition performance of vessels across varying scales under challenging maritime conditions. This is achieved through the integration of three key components: a HiLo attention mechanism, a bidirectional feature pyramid network (BiFPN), and a downsampling module based on Haar wavelets. With Ship-DETR’s FLOPs reaching 43.5 G, the model structure is relatively complex, and it still carries a risk of missed detections in scenarios involving extremely small or densely occluded targets. Jiao et al. [36] adopted an FCDS-DETR model (based on the DETR architecture) as the baseline. By integrating a two-dimensional Gaussian probability density distribution into the attention mechanism alongside a denoising training strategy, their approach markedly enhanced the recognition capability for small-scale objects within low-altitude unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) imagery captured over maritime environments. However, the model’s high complexity—reaching 190 G FLOPs—and low inference speed—only 5 FPS on the AFO dataset—limit its practical application, and its adaptability to densely occluded scenes remains insufficient.

3. MCB-RT-DETR Algorithm Design

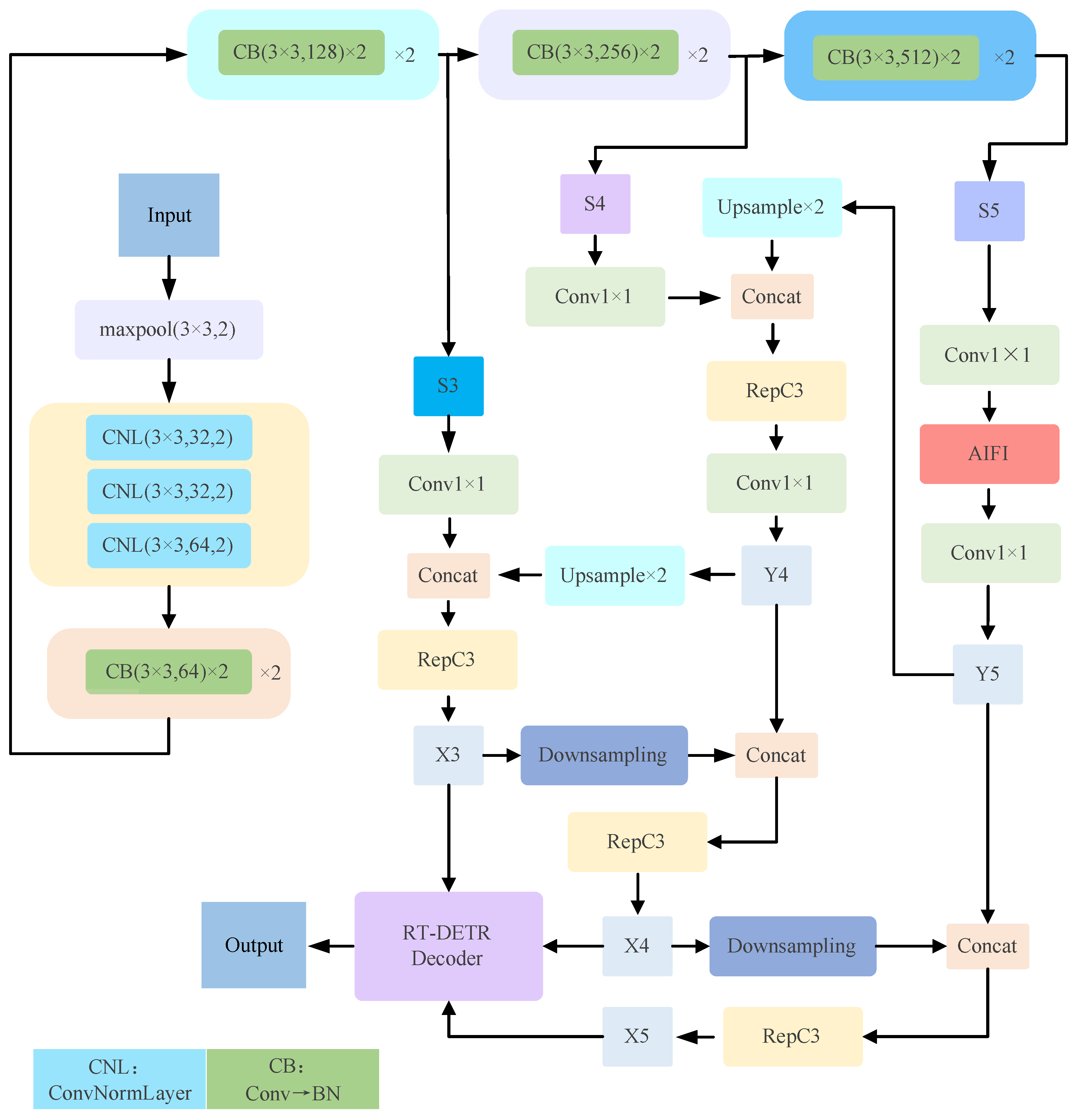

3.1. Baseline Model Analysis

- (1)

- Insufficient Feature Discrimination and Anti-Interference Capability: The baseline model’s feature extraction and fusion mechanisms have limited adaptability to the maritime environment. In the ResNet-18 backbone, standard convolution and basic attention layers often filter out vital high-frequency details, like ship edge textures, during feature downsampling. Concurrently, the encoder’s global attention mechanism struggles to consistently focus on real targets against the homogeneous sea background. This leads to inadequate suppression of interference like waves and cloud shadows.

- (2)

- Limited Feature Representation for Small Targets: The existing feature pyramid structure (e.g., Cross-Scale Feature Fusion Module, CCFM) primarily serves targets of conventional scales. For distant ships occupying extremely few pixels, high-level features, while semantically rich, suffer severe loss of spatial detail. Conversely, low-level high-resolution features are not effectively utilized due to computational complexity and channel number limitations. This results in degraded small target detection performance.

- (3)

- Inadequate Adaptation to Multi-Scale Differences: The original model employs regular upsampling operations (e.g., nearest-neighbor interpolation) in its neck network. These methods calculate pixel values using fixed rules, ignoring the semantic content of the feature maps. When facing ship targets exhibiting drastic scale changes from close-range to long-range, this content-insensitive sampling approach easily causes feature blurring. This consequently leads to inaccurate localization or missed detections.

- (4)

- Mismatch Between Computational Efficiency and Deployment Requirements: Although RT-DETR-R18 is a relatively lightweight version, certain operations in its neck network (e.g., regular upsampling) present a contradiction between detail reconstruction capability and computational overhead. Further lightweight improvements are still necessary to achieve efficient deployment on resource-constrained platforms like UAVs.

3.2. Backbone Network Improvements

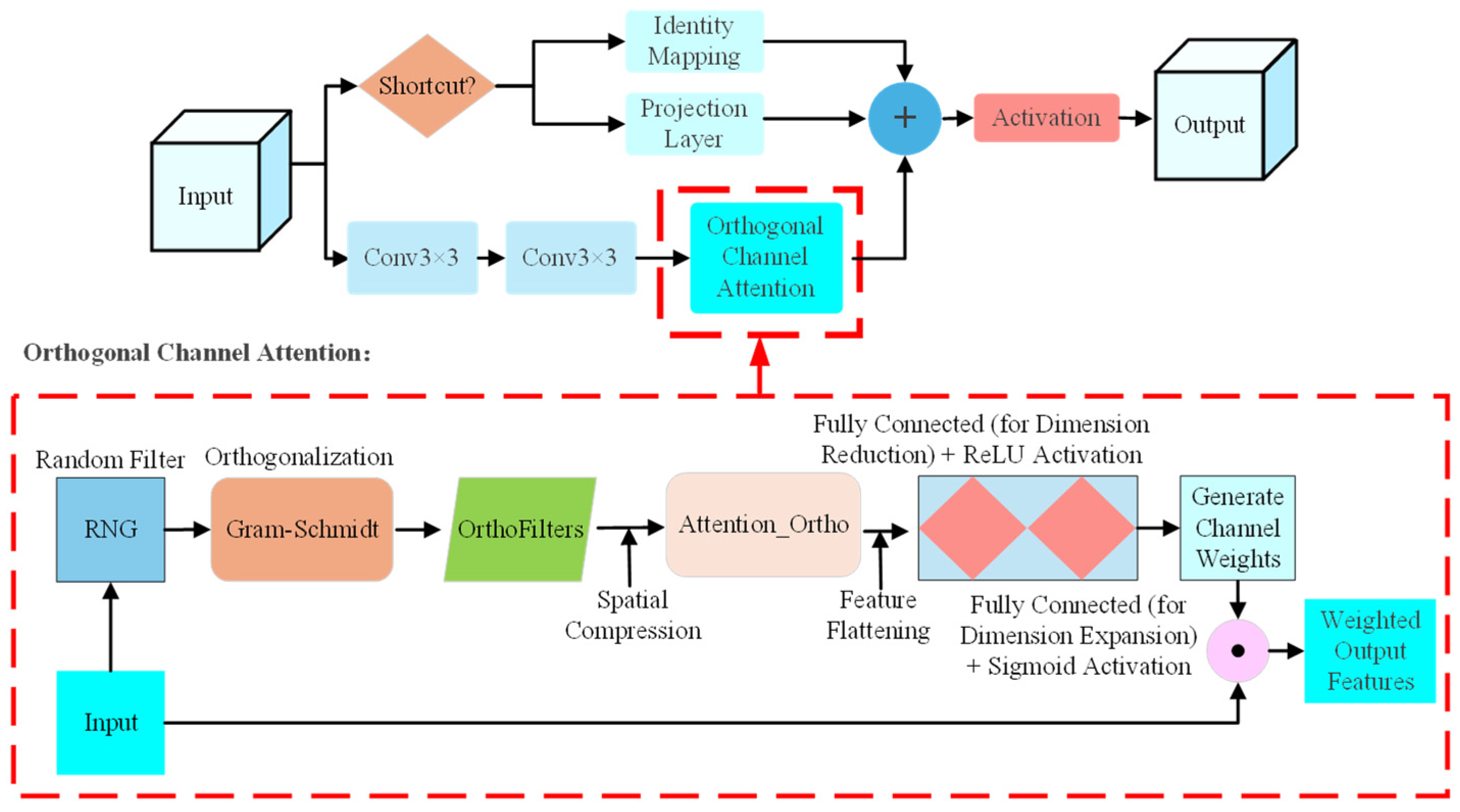

3.2.1. Introducing the Ortho Attention Mechanism

- (1)

- A random orthogonal filter bank is generated to compress spatial information into a compact channel descriptor. This filter bank is constructed via Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization and remains fixed (non-learnable), ensuring an unbiased projection of input features.

- (2)

- Attention Calculation Stage:

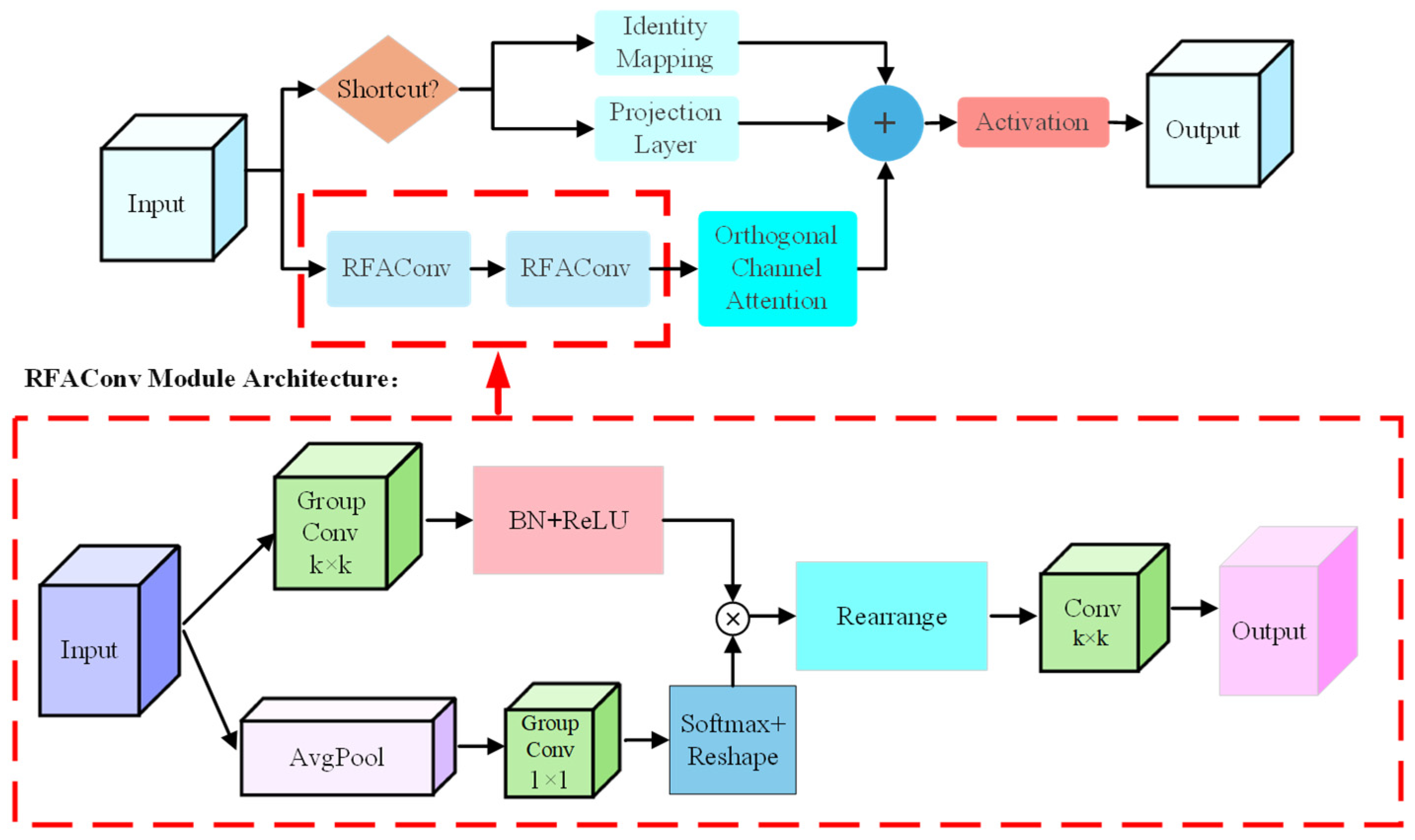

3.2.2. Introducing RFAConv Convolution

- (1)

- Receptive field feature extraction: Using group convolution (number of groups equals input channel count C), we expand each receptive field of input feature into a vector. This yields the receptive field feature .

- (2)

- Attention weight generation: The attention weight map is generated through the hierarchical feature interaction protocol described above, where each weight reflects the learned importance of corresponding spatial position within its receptive field context.

- (3)

- Weighted feature fusion: Apply the attention weights to the receptive field features to obtain the weighted features .

- (4)

- Feature reorganization and convolution: Reshape the weighted features back to spatial dimensions. Next, a standard convolution layer with a kernel and stride size of k performs downsampling and feature fusion, producing the final feature map.

3.3. Design of Small Object Detail-Enhancement Pyramid (SOD-EPN)

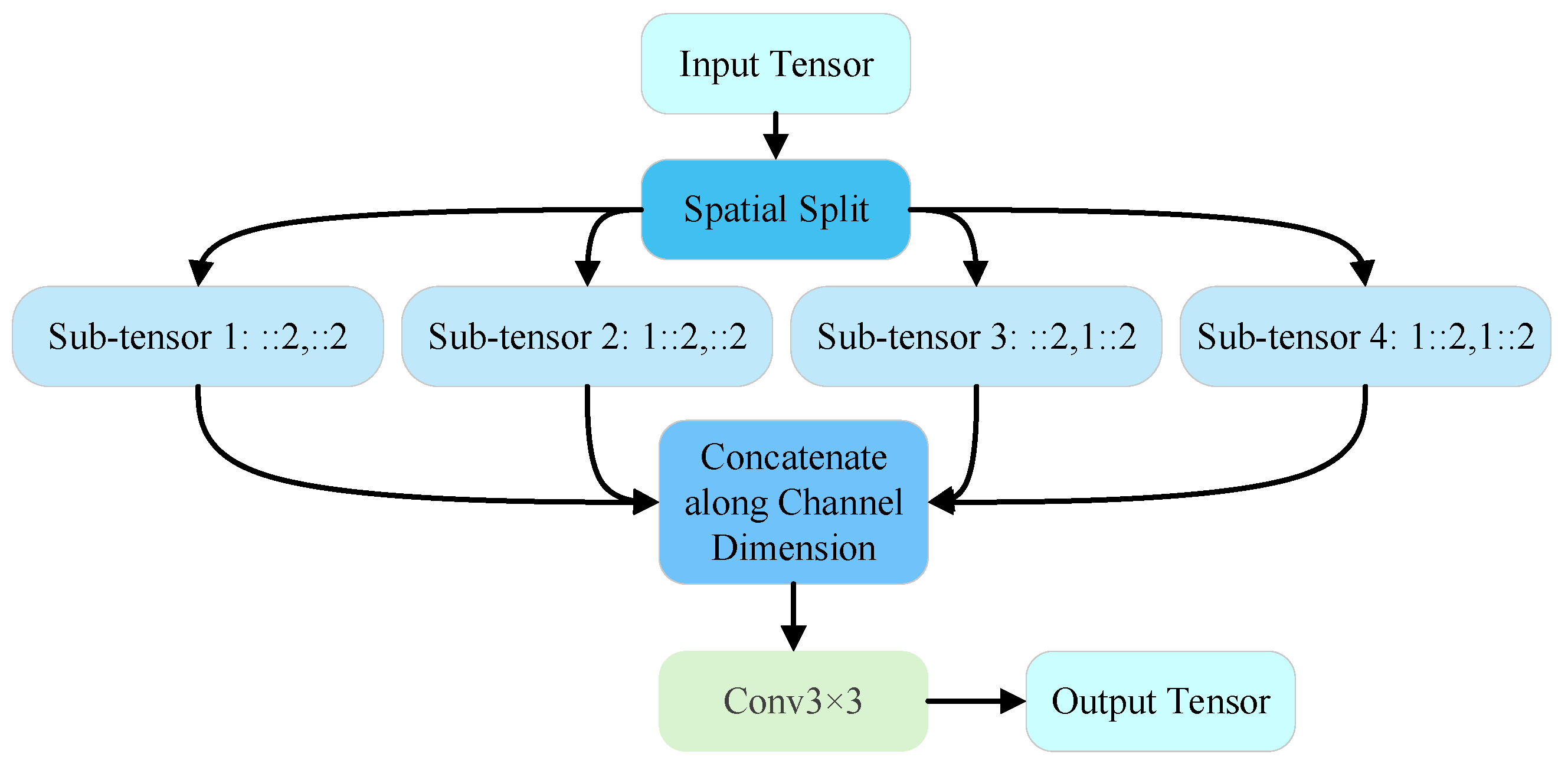

3.3.1. Spatial Compression with SPDConv

3.3.2. Multi-Scale Fusion with CSP-OmniKernel

3.4. Lightweight Neck Network

- (1)

- Continuous signal modeling: Apply bilinear interpolation to the input feature map to obtain the continuous representation , as shown in Equation (9):where denotes bilinear interpolation; is the target upsampling rate.

- (2)

- Offset prediction: Predict position offsets for each target pixel using a lightweight network (composed of depth-wise separable convolution and point convolution). as shown in Equation (10)

- (3)

- Dynamic sampling execution: Combine the continuous signal and offset field . Resample at dynamically generated sampling points to obtain the final high-resolution output .

4. Results

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

4.1.1. Datasets

- SeaDronesSee [44]: A large-scale dataset specifically constructed for UAV maritime visual tasks. We follow the official split: 8930 training images, 1547 validation images, and 3750 test images. The image resolutions range from 1080p to 4K, and we uniformly resize them to 640 × 640 for training. The dataset contains 5 categories, with the ‘boat’ category constituting the majority of instances. The target scales exhibit a long-tailed distribution characterized by “small when far, large when near,” with complex backgrounds, making it ideal for validating performance in real maritime scenarios.

- DIOR [45]: A large-scale optical remote sensing image object detection dataset. Following the official split of 11,725 training images and 11,738 test images, we train on the entire training set and specifically evaluate the ‘ship’ category on the test set (comprising 35,186 instances in total). All images have a uniform resolution of 800 × 800 pixels.

- VisDrone2019 [46]: One of the most challenging UAV aerial object detection datasets currently available. We use its training set (6471 images) for training and evaluate generalization performance across all 10 categories on the validation set (548 images). The images have varying resolutions and are similarly resized to 640 × 640.

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

- Mean Average Precision (mAP): We use mAP@0.5 (mAP at IoU threshold of 0.5) as the main metric to measure the model’s comprehensive detection ability. Additionally, we report mAP@0.5:0.95 (average mAP over IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step of 0.05) to evaluate localization accuracy.

- Precision and Recall: Precision (P) measures the reliability of detection results; Recall (R) measures the model’s ability to cover real targets.

- Frames Per Second (FPS): We test the average time to process a single image on a single NVIDIA RTX3090 GPU and calculate FPS to evaluate the model’s inference speed.

- Params (M): We report the number of model parameters in millions (M) to indicate model complexity and memory footprint.

- FLOPs (G): We calculate the number of floating-point operations (in gigaFLOPs, G) for a standard input size to assess.

4.1.3. Implementation Details

4.2. Ablation Experiments

- (1)

- Module Effectiveness: The addition of any single module improves the baseline model’s mAP@0.5, validating the effectiveness of each proposed component. Specifically: (a) SOD-EPN provides the largest recall improvement (+5.7%), significantly reducing small target missed detections; (b) DySample substantially boosts inference speed (+20.7% FPS) while maintaining competitive accuracy; (c) RFAConv achieves the best single-module mAP@0.5 improvement (+2.7%). We also evaluated a learnable variant of the orthogonal filter (Table 2, row “+Ortho (Learn)”), which underperforms the static version in both mAP@0.5 and recall, validating our design choice of using a static kernel to ensure unbiased feature preservation and avoid optimization bias.

- (2)

- Combination Effects: The integration of different modules reveals complementary strengths. On one hand, the Ortho + RFAConv combination achieves the highest precision (93.1%) and overall mAP@0.5:0.95 (49.4%), demonstrating that enhancements to the backbone effectively boost feature discriminability. On the other hand, the SOD-EPN + DySample combination attains the highest detection accuracy mAP@0.5 (83.6%) but at a reduced inference speed of 36.4 FPS, highlighting the inherent accuracy-speed trade-off in feature pyramid design. Specifically, while SOD-EPN preserves high-resolution detail features and DySample performs dynamic content-aware upsampling, their direct combination introduces additional computational overhead when processing multi-scale features, which is the primary cause of the speed reduction.

- (3)

- Final Model: The complete MCB-RT-DETR (integrating all modules with architectural optimizations including feature resolution alignment between SOD-EPN and DySample, selective module integration based on complementary analysis, and inference pipeline optimizations through layer fusion) achieves the optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency: mAP@0.5 increases by 4.5% (from 78.4% to 82.9%), mAP@0.5:0.95 improves by 3.4% (from 46.3% to 49.7%), while maintaining real-time processing at 50 FPS. With 22.11 M parameters and 65.2 G FLOPs, the model demonstrates reasonable computational complexity for the achieved performance level, verifying the superiority of our multi-module collaborative design.

- (4)

- Small-target Detection Focus: Given the SeaDronesSee dataset composition (88.4% small targets), the substantial recall improvement (from 75.0% to 81.0%) is particularly significant, demonstrating our method’s effectiveness in addressing the primary challenge of maritime UAV operations—detecting small and distant vessels.

- (5)

- Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis: We conducted a sensitivity analysis on the key hyperparameter in DySample—the offset range factor . Values of were tested on the SeaDronesSee validation set. The results show that with , the model is too conservative, yielding a limited mAP@0.5 improvement (+1.3%). When , the excessive offset range leads to local distortion in the feature space, causing the accuracy to drop (mAP@0.5 only + 0.8%) and a slight decrease in FPS. In contrast, achieves a significant accuracy gain (mAP@0.5 + 1.6%) while maintaining the highest FPS, validating this empirical value as a good trade-off between accuracy and efficiency.

4.3. Comparative Experiments

4.4. Generalization Verification

4.4.1. Ship Detection on DIOR Dataset

4.4.2. General Object Detection on VisDrone2019 Dataset

5. Discussion

5.1. Module Collaboration Mechanism Analysis

5.2. Internal Reasons for Performance Advantages

5.3. Practical Application Prospects and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lau, Y.-Y.; Chen, Q.; Poo, M.C.-P.; Ng, A.K.Y.; Ying, C.C. Maritime transport resilience: A systematic literature review on the current state of the art, research agenda and future research directions. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 251, 107086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensado, E.A.; López, F.V.; Jorge, H.G.; Pinto, A.M. UAV Shore-to-Ship Parcel Delivery: Gust-Aware Trajectory Planning. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 6213–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, N.; Park, Y.W.; Won, C.S. Object Detection and Classification Based on YOLO-V5 with Improved Maritime Dataset. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Zheng, W.; Xu, Y. YOLO-SEA: An Enhanced Detection Framework for Multi-Scale Maritime Targets in Complex Sea States and Adverse Weather. Entropy 2025, 27, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Yang, W.; Jiao, Y.; Geng, L.; Chen, X. SCA-YOLO: A new small object detection model for UAV images. Vis. Comput. 2024, 40, 1787–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, L. Ship Plate Detection Algorithm Based on Improved RT-DETR. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Fan, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, Y. CGDU-DETR: An End-to-End Detection Model for Ship Detection in Day–Night Transition Environments. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, F.F.; Chen, L.; Shao, J.; Ji, W.; Xiao, S.; Ye, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Xiao, J. Deep Learning for Weakly-Supervised Object Detection and Localization: A Survey. Neurocomputing 2022, 496, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Long, L.; Liu, N.; Wan, Q. Improved K-means Template Matching Target Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE 6th International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence, Xiamen, China, 18–20 August 2023; pp. 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, N.; Moon, K.-S.; Kim, J.-N. An adaptive moving ship detection and tracking based on edge information and morphological operations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Graphic and Image Processing, Cairo, Egypt, 1–2 October 2011; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2011; pp. 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Chen, L.-C.; Yuille, A. Detectors: Detecting objects with recursive feature pyramid and switchable atrous convolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 10213–10224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of theComputer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, R.; Sambath, M. YOLOv8: A Novel Object Detection Algorithm with Enhanced Performance and Robustness. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems, Chennai, India, 15–16 March 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alif, M.A.R.; Hussain, M. Yolov12: A breakdown of the key architectural features. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.14740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.C.; Alfred, R.; Pailus, R.H.; Ge, L.; Shifeng, D.; Chew, J.V.L.; Guozhang, L.; Xinliang, W. DETR Novel Small Target Detection Algorithm Based on Swin Transformer. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 115838–115852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Cao, H. SDFA-Net: Synergistic Dynamic Fusion Architecture with Deformable Attention for UAV Small Target Detection. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 110636–110647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Ni, L.M.; Zhang, L. Dn-detr: Accelerate detr training by introducing query denoising. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 13619–13627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, C. GGT-YOLO: A novel object detection algorithm for drone-based maritime cruising. Drones 2022, 6, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, C.; Yu, K.; Yin, K.; Huang, H.; Yang, G.; Li, F.; Zhou, Z. YOLO-UAVShip: An Effective Method and Dataset for Multi-View Ship Detection in UAV Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Song, L.; Ge, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Shan, Y. Yolo-world: Real-time open-vocabulary object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 16901–16911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Zeng, W.M.; Zhang, X.L. HFPNet: Super Feature Aggregation Pyramid Network for Maritime Remote Sensing Small-Object Detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 5973–5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Zhang, Y. LiteFlex-YOLO: A lightweight small target detection network for maritime unmanned aerial vehicles. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2025, 111, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Ren, J.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y. S-DETR: A Transformer Model for Real-Time Detection of Marine Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X. Ship-DETR: A Transformer-Based Model for Efficient Ship Detection in Complex Maritime Environments. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 66031–66039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Wang, M.; Qiao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z. Transformer-Based Object Detection in Low-Altitude Maritime UAV Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4210413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, H.; Parks, C.; Swan, M.; Gauch, J. Orthonets: Orthogonal channel attention networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Big Data, Sorrento, Italy, 15–18 December 2023; pp. 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Yang, D.; Song, T.; Ye, Y.; Li, K.; Song, Y. RFAConv: Innovating spatial attention and standard convolutional operation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.03198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkara, R.; Luo, T. No more strided convolutions or pooling: A new CNN building block for low-resolution images and small objects. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Grenoble, France, 19–23 September 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M.; Wu, Y.-H.; Chen, P.-Y.; Hsieh, J.-W.; Yeh, I.-H. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 390–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Ren, W.; Knoll, A. Omni-kernel network for image restoration. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; pp. 1426–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lu, H.; Fu, H.; Cao, Z. Learning to upsample by learning to sample. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 6027–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Hu, Q.; Dong, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, B.; Zhong, P. Lighten CARAFE: Dynamic lightweight upsampling with guided reassemble kernels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–25 August 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, L.A.; Kiefer, B.; Messmer, M.; Zell, A. Seadronessee: A maritime benchmark for detecting humans in open water. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 2260–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wan, G.; Cheng, G.; Meng, L.; Han, J. Object detection in optical remote sensing images: A survey and a new benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Bian, X.; Lin, H.; Hu, Q. VisDrone-DET2019: The vision meets drone object detection in image challenge results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhang, P.; Geng, T.; Yuan, X.; Ji, B.; Zhu, S.; Ma, R. MFEF-YOLO: A Multi-Scale Feature Extraction and Fusion Network for Small Object Detection in Aerial Imagery over Open Water. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hua, Y.; Xue, M. MSO-DETR: A Lightweight Detection Transformer Model for Small Object Detection in Maritime Search and Rescue. Electronics 2025, 14, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| GPU | NVIDIA RTX 3090 |

| Framework | PyTorch 2.0.0 |

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Initial learning rate | 1 × 10−4 |

| Weight decay | 1 × 10−4 |

| LR scheduler | Cosine annealing (lrf = 0.001) |

| Training epochs | 200 |

| Input image size | 640 × 640 |

| Batch size | 4 |

| Model | P/% | R/% | mAP@ 0.5/% | mAP@0.5: 0.95/% | FPS | Params(M) | FLOPs(G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 91.1 | 75.0 | 78.4 | 46.3 | 50.8 | 20.10 | 58.3 |

| +Ortho | 91.1 | 77.3 | 79.3 | 47.1 | 44.8 | 20.25 | 60.5 |

| +Ortho (Learn) | 90.5 | 76.8 | 78.9 | 46.8 | 44.5 | 20.26 | 60.9 |

| +RFAConv | 91.4 | 79.6 | 81.1 | 48.1 | 46.7 | 20.40 | 61.8 |

| +SOD-EPN | 91.4 | 80.7 | 82.5 | 47.7 | 50.5 | 21.61 | 63.6 |

| +DySample | 89.4 | 77.1 | 80.0 | 46.8 | 61.3 | 20.12 | 56.4 |

| +Ortho + RFAConv | 93.1 | 78.1 | 82.1 | 49.4 | 42.6 | 20.65 | 65.3 |

| +SOD-EPN + DySample | 91.0 | 80.7 | 83.6 | 47.3 | 36.4 | 21.62 | 67.7 |

| MCB-RT-DETR (all) | 90.8 | 81.0 | 82.9 | 49.7 | 50.0 | 22.11 | 65.2 |

| Model | P/% | R/% | mAP@0.5/% | mAP@0.5:0.95/% | FPS | Params(M) | FLOPs(G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv10 | 73.8 | 55.0 | 61.0 | 36.0 | 114.9 | 2.71 | 8.2 |

| YOLOv11 | 76.4 | 57.6 | 61.0 | 37.0 | 140.8 | 2.60 | 6.3 |

| YOLOv12 | 80.3 | 63.4 | 68.7 | 41.7 | 77.5 | 2.55 | 6.5 |

| YOLOv13 | 80.4 | 62.3 | 67.3 | 40.7 | 54.6 | 2.46 | 6.4 |

| MFEF-YOLO | 75.8 | 68.4 | 71.2 | 41.0 | 99.1 | 2.3 | 11.7 |

| MSO-DETR | 91.0 | 75.3 | 78.2 | 46.9 | 53.7 | 6.5 | 30.5 |

| DN-DETR | 75.2 | 56.6 | 60.1 | 36.2 | 31.5 | 44.0 | 94.1 |

| Ours | 90.8 | 81.0 | 82.9 | 49.7 | 50.0 | 22.11 | 65.2 |

| Model | P/% | R/% | mAP@0.5/% | mAP@0.5:0.95/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8 | 93.5 | 88.9 | 93.5 | 58.8 |

| YOLOv11 | 94.5 | 90.1 | 94.6 | 59.1 |

| RT-DETR-R18 | 93.0 | 93.1 | 94.8 | 60.8 |

| Ours | 95.5 | 91.9 | 95.7 | 62.4 |

| Method | P/% | R/% | mAP@0.5/% | mAP@0.5:0.95/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv11 | 42.0 | 32.8 | 32.5 | 18.9 |

| RT-DETR-R18 | 61.7 | 44.3 | 46.4 | 28.2 |

| Ours | 61.5 | 47.3 | 48.0 | 29.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, F.; Wei, Y.; Yan, A.; Cao, T.; Xie, X. MCB-RT-DETR: A Real-Time Vessel Detection Method for UAV Maritime Operations. Drones 2026, 10, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010013

Liu F, Wei Y, Yan A, Cao T, Xie X. MCB-RT-DETR: A Real-Time Vessel Detection Method for UAV Maritime Operations. Drones. 2026; 10(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Fang, Yongpeng Wei, Aruhan Yan, Tiezhu Cao, and Xinghai Xie. 2026. "MCB-RT-DETR: A Real-Time Vessel Detection Method for UAV Maritime Operations" Drones 10, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010013

APA StyleLiu, F., Wei, Y., Yan, A., Cao, T., & Xie, X. (2026). MCB-RT-DETR: A Real-Time Vessel Detection Method for UAV Maritime Operations. Drones, 10(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010013