MSG-GCN: Multi-Semantic Guided Graph Convolutional Network for Human Overboard Behavior Recognition in Maritime Drone Systems

Highlights

- Enhanced discrimination between similar actions through multi-semantic guidance and fine-grained modeling.

- Development of a lightweight action recognition network via a concise and efficient hierarchical design.

- This study provides an action recognition algorithm suitable for complex environments, offering high accuracy and robustness.

- The lightweight design enables deployment on resource-constrained platforms such as unmanned aerial vehicles.

Abstract

1. Introduction

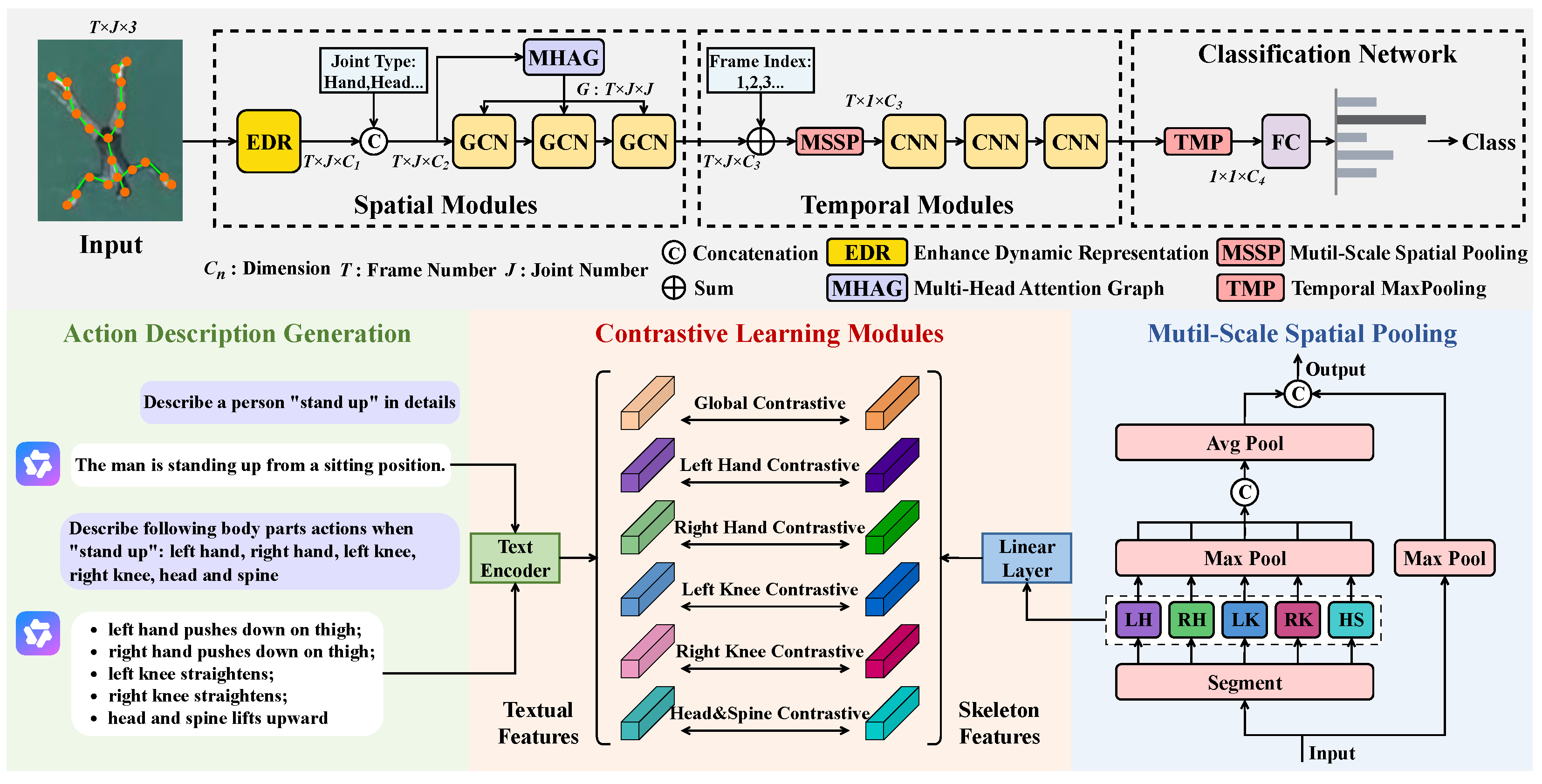

- We propose MSG-GCN, a novel framework that explicitly incorporates joint-type and frame-index semantics, and further integrates textual semantic supervision to achieve multi-level semantic alignment of skeletal features, thereby enhancing feature representation in both spatial and temporal dimensions.

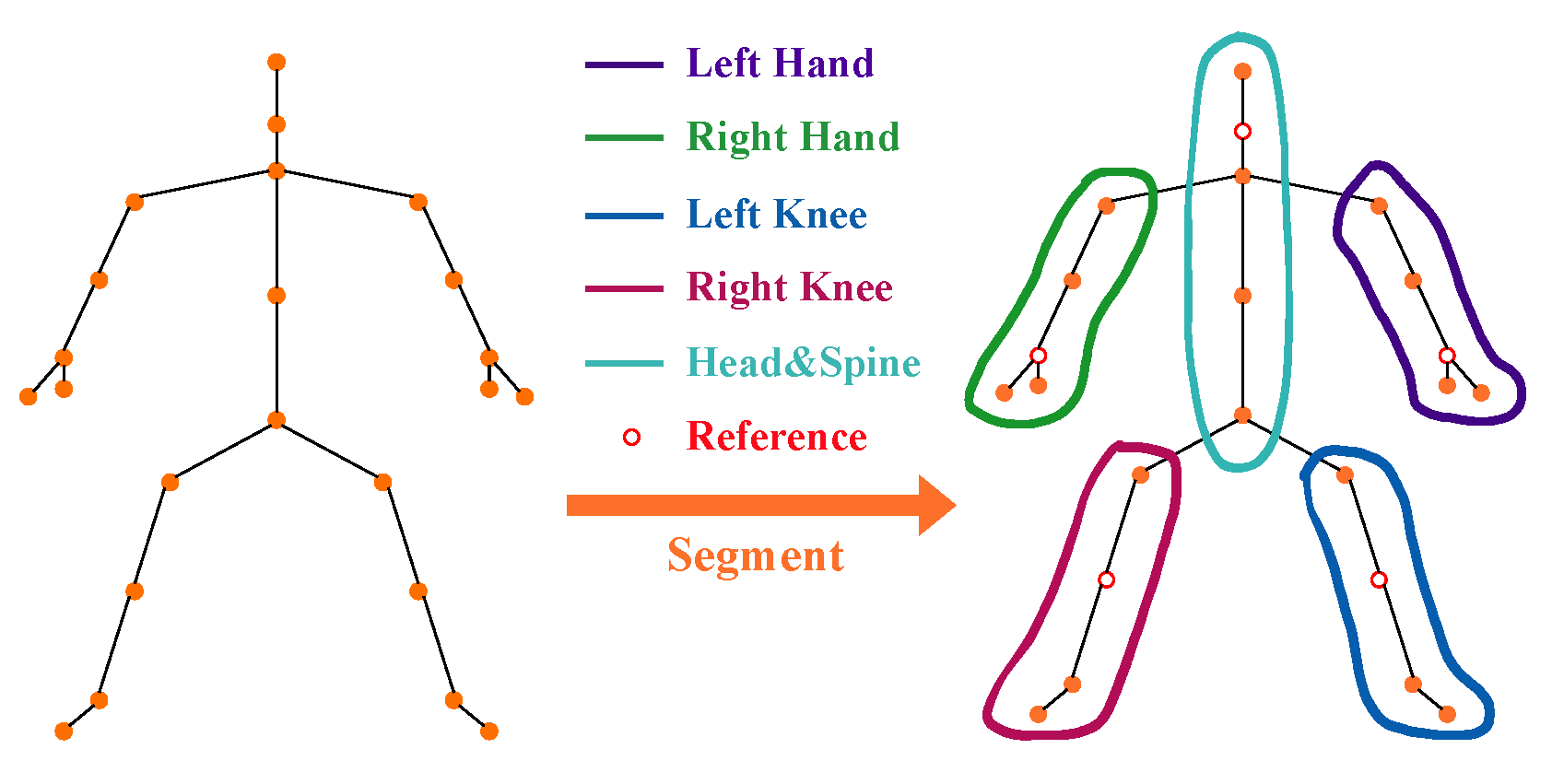

- We design a fine-grained modeling strategy that strengthens dynamic feature representations and leverages multi-scale spatial pooling to effectively fuse local patterns of different body parts with global action information, improving the discriminability and robustness of feature representations.

- The proposed MSG-GCN is a lightweight graph convolutional network that, through multi-semantic guidance and multi-scale feature interaction, achieves state-of-the-art performance on four large-scale benchmark datasets while requiring fewer parameters.

2. Related Work

2.1. Human Action Recognition

2.2. Prompt Learning

3. Method

3.1. Spatial Modules

3.2. Temporal Modules

3.3. Loss Function

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Ablation Study

4.3.1. Effectiveness of MSG-GCN

4.3.2. Effectiveness of MS

4.3.3. Impact of Different MHAG Modes

4.3.4. Impact of Different MSSP Modes

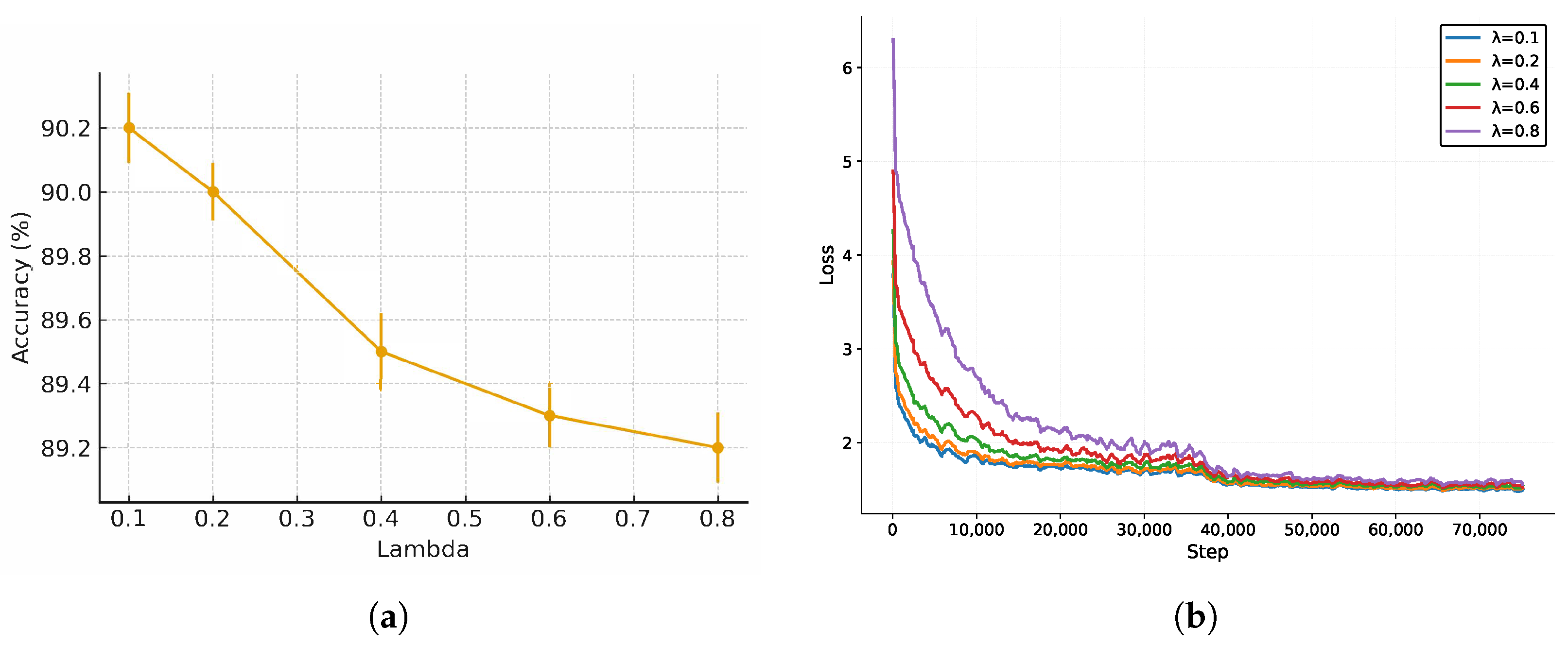

4.3.5. Impact of Loss Function

4.3.6. Impact of Text-Encoder and Prompt

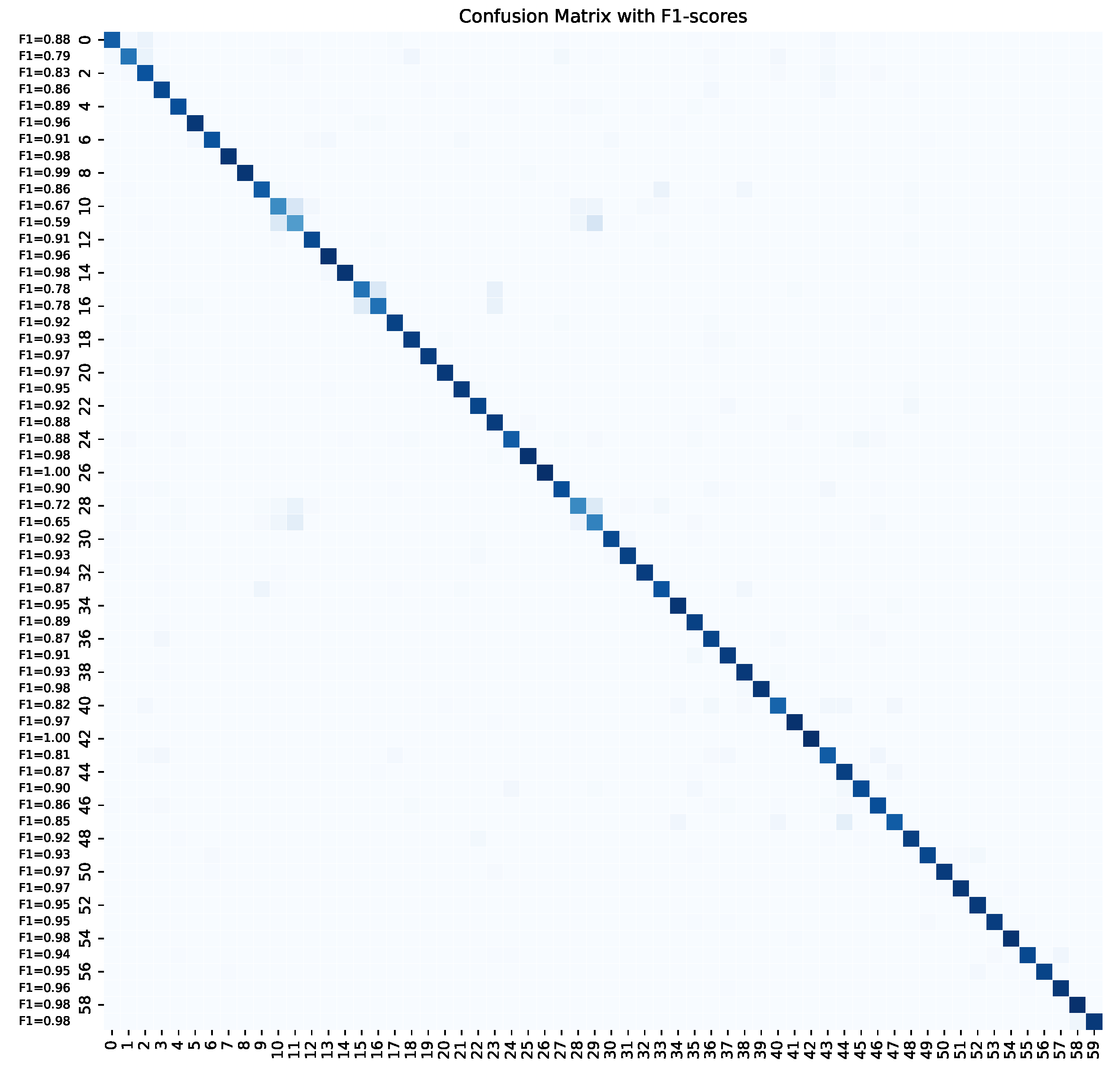

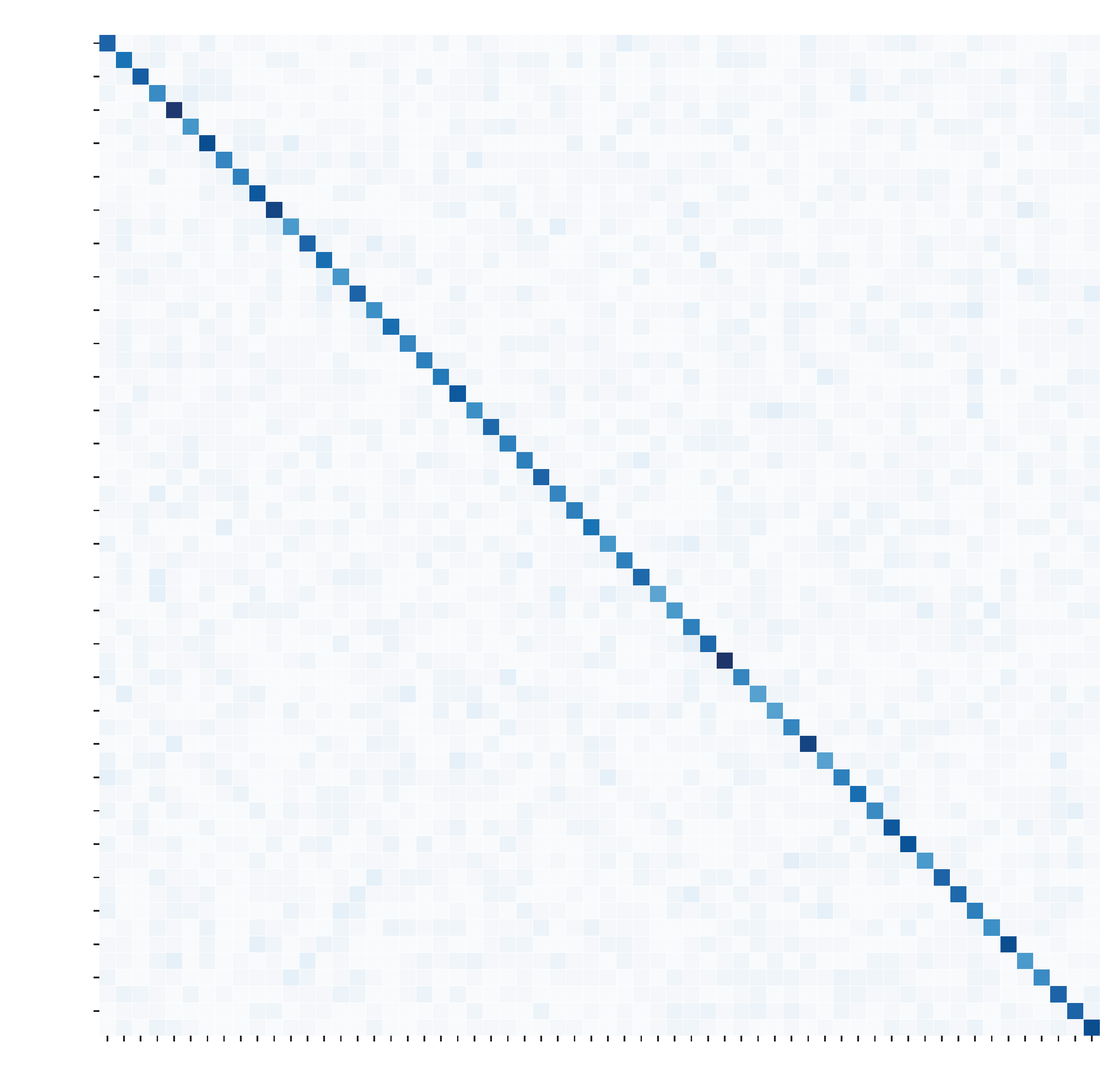

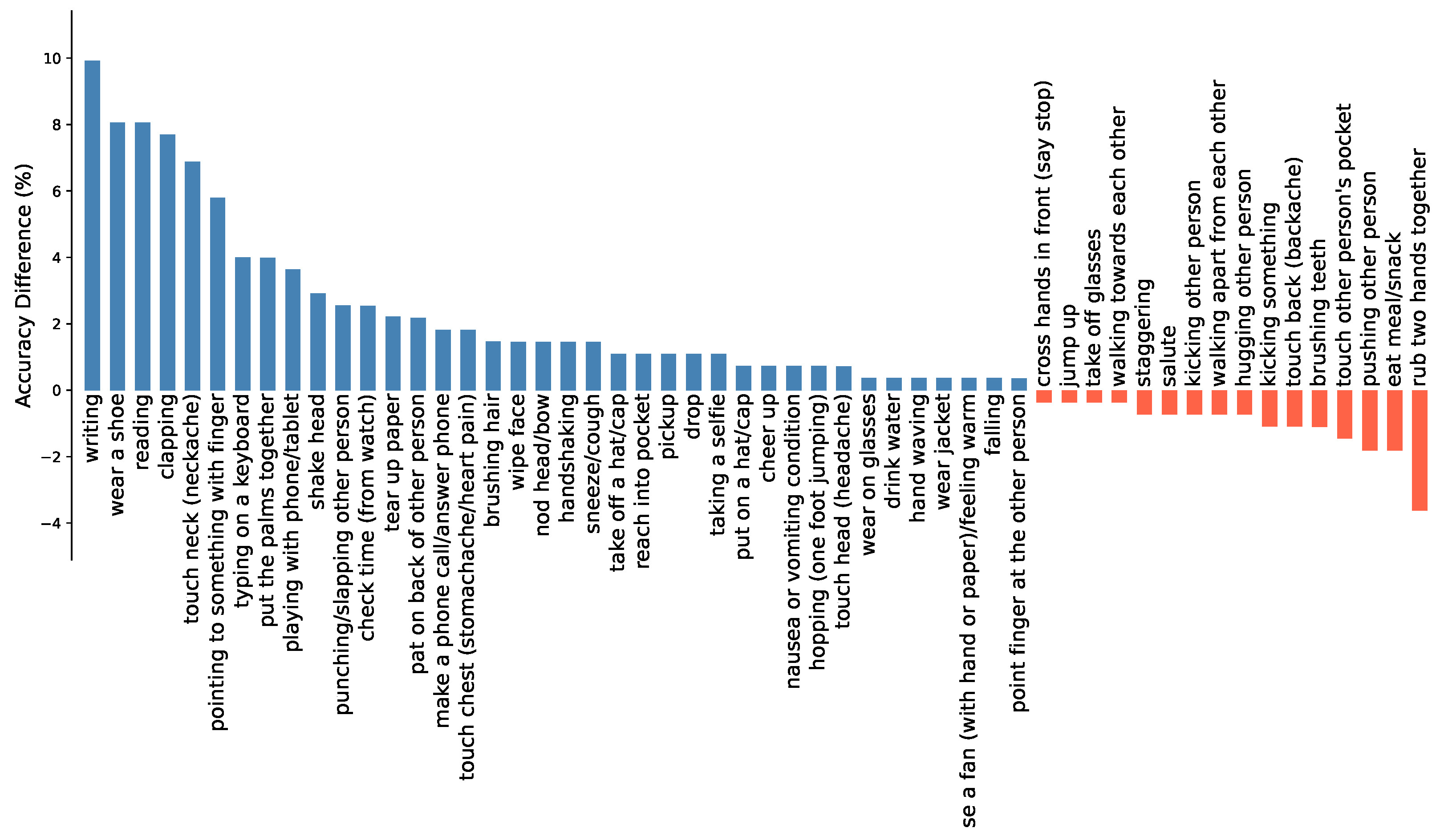

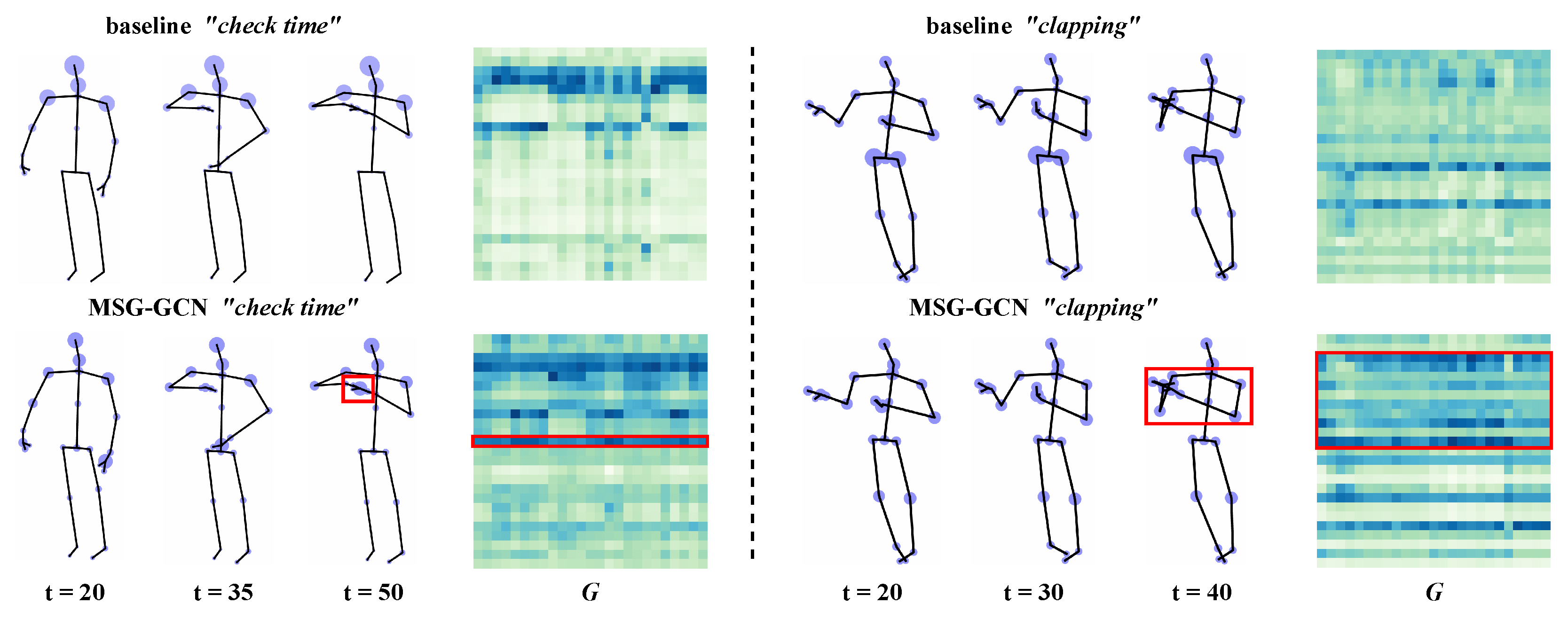

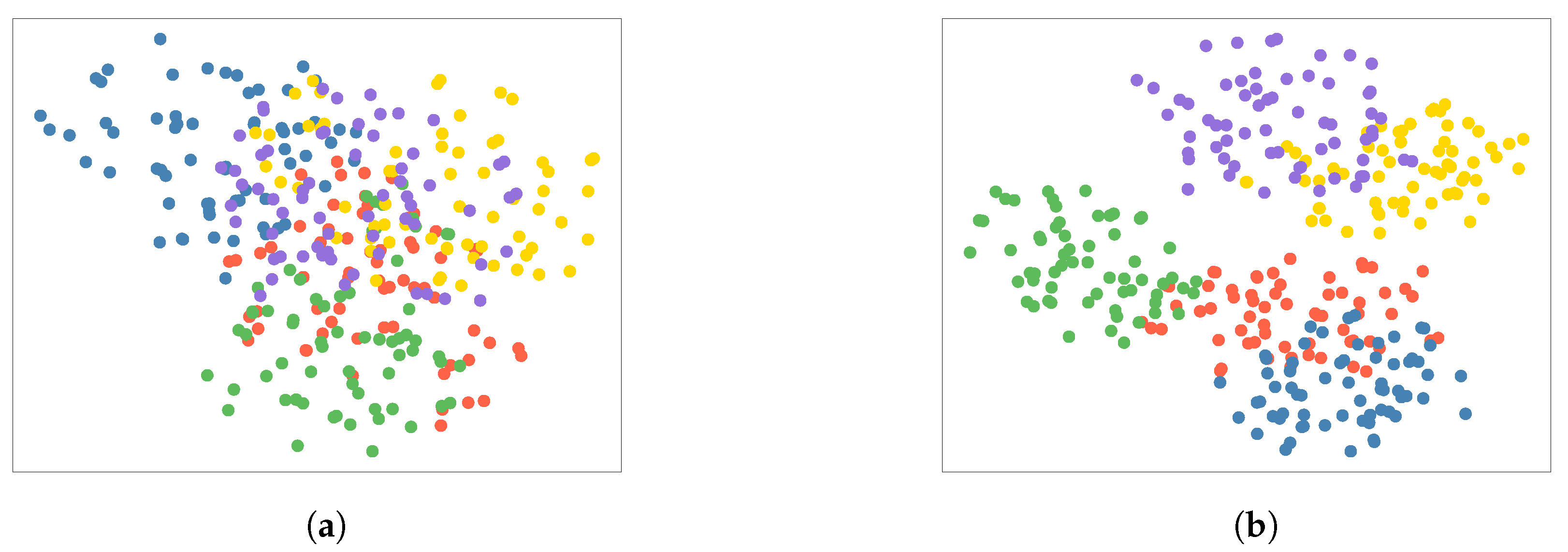

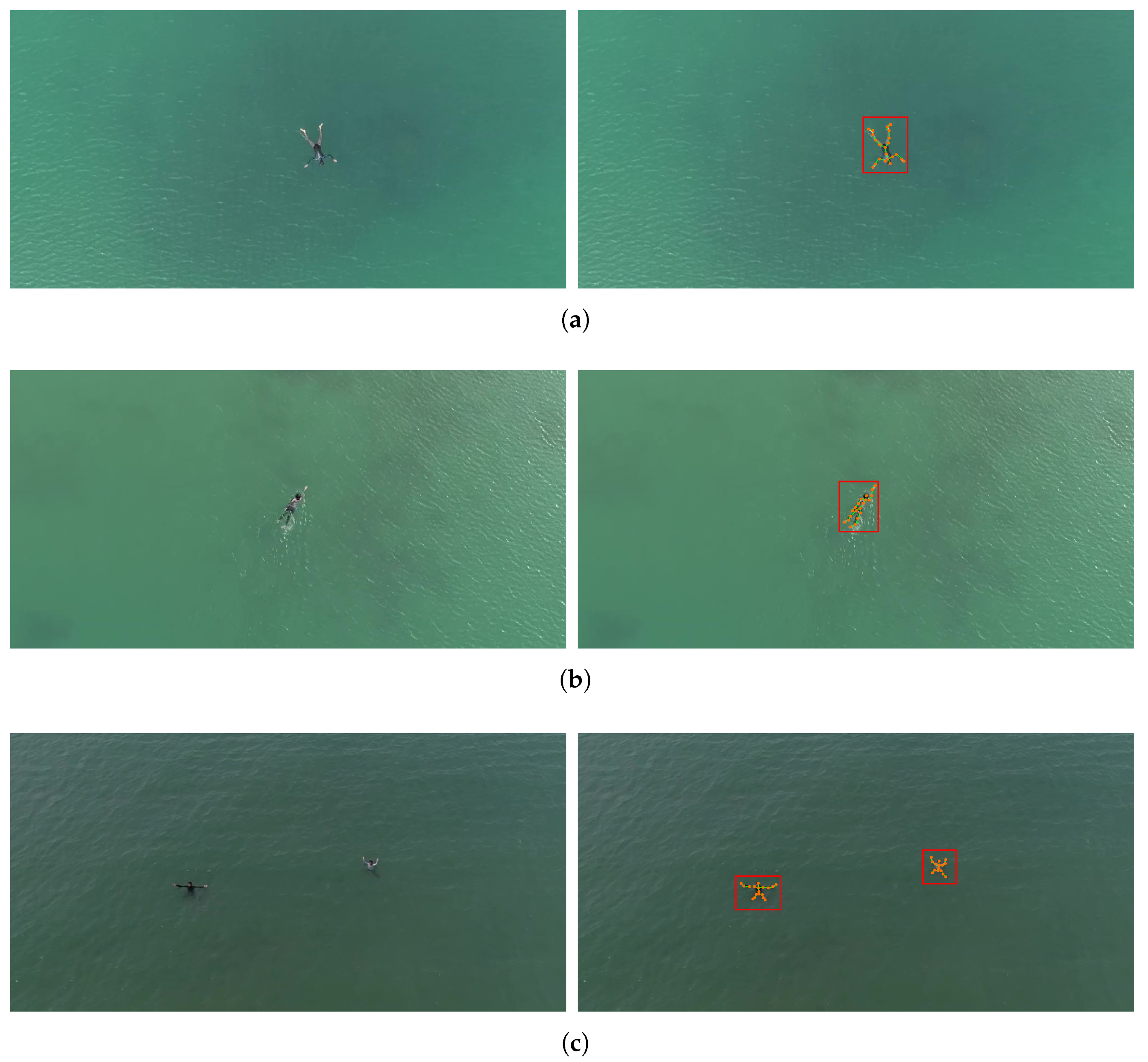

4.4. Visualization

4.5. Comparison with the State-of-the-Arts

4.6. Validation of MSG-GCN for Maritime Search and Rescue Applications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Confusion Matrix

References

- Li, B.; Yang, Z.P.; Chen, D.Q.; Liang, S.Y.; Ma, H. Maneuvering target tracking of UAV based on MN-DDPG and transfer learning. Def. Technol. 2021, 17, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, B.; Huang, J.; Song, C.; He, P.; Neretin, E. A Parallel Multi-Demonstrations Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning Approach on UAV Target Tracking Decision. Chin. J. Electron. 2025, 34, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, J.; Song, C.; Yang, Z.; Wan, K.; Zhang, Q. Multi-UAV roundup strategy method based on deep reinforcement learning CEL-MADDPG algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 245, 123018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Sun, Y. A Combined Intrusion Strategy Based on Apollonius Circle for Multiple Mobile Robots in Attack-Defense Scenario. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 10, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Li, H.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Tian, C. Distributed Robust Data-Driven Event-Triggered Control for QUAVs under Stochastic Disturbances. Def. Technol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, K.; Xing, W.; Li, H.; Yang, Z. Applications, evolutions, and challenges of drones in maritime transport. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobick, A.F.; Davis, J.W. The recognition of human movement using temporal templates. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 23, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Ishwar, P.; Konrad, J. Action recognition using sparse representation on covariance manifolds of optical flow. In Proceedings of the 2010 7th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance, Boston, MA, USA, 29 August–1 September 2010; pp. 188–195. [Google Scholar]

- Salmane, H.; Ruichek, Y.; Khoudour, L. Object tracking using Harris corner points based optical flow propagation and Kalman filter. In Proceedings of the 2011 14th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Washington, DC, USA, 5–7 October 2011; pp. 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, L. Hierarchical recurrent neural network for skeleton based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1110–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I.; Kim, D.; Kang, S.; Lee, S. Ensemble deep learning for skeleton-based action recognition using temporal sliding lstm networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1012–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, L. Modeling temporal dynamics and spatial configurations of actions using two-stream recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 499–508. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Li, W.; Li, C.; Hou, Y. Action recognition based on joint trajectory maps with convolutional neural networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2018, 158, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Lan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Y. Skeleton-based action recognition with gated convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2018, 29, 3247–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xia, R.; Liu, X.; Huang, Q. Learning shape-motion representations from geometric algebra spatio-temporal model for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Shanghai, China, 8–12 July 2019; pp. 1066–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, K.; Lin, D.; Dai, B. Revisiting skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 2969–2978. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Lin, D. Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lu, H. Two-stream adaptive graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 12026–12035. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ouyang, W. Disentangling and unifying graph convolutions for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, C.; Li, B.; Deng, Y.; Hu, W. Channel-wise topology refinement graph convolution for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 13359–13368. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, D.; He, K. Graph transformer network with temporal kernel attention for skeleton-based action recognition. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 240, 108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhan, M.; Zhang, H.; Luo, Q.; Tang, K. MTGCN: A multi-task approach for node classification and link prediction in graph data. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 102902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Gao, Y.; Hui, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, X. Language knowledge-assisted representation learning for skeleton-based action recognition. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 5784–5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liang, W.; Yin, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z. Semantic information guided multimodal skeleton-based action recognition. Inf. Fusion 2025, 123, 103289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Li, B.; Liu, X.; Gao, X.; Wan, K. Low-high frequency network for spatial–temporal traffic flow forecasting. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 158, 111304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Song, J.; Zhou, Q.; Rasol, J.; Ma, L. Planet Craters Detection Based on Unsupervised Domain Adaptation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 7140–7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, J.; Loy, C.C.; Liu, Z. Learning to prompt for vision-language models. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Constant, N. The power of scale for parameter-efficient prompt tuning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.08691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Liang, P. Prefix-tuning: Optimizing continuous prompts for generation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.00190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hua, H.; Yang, Z.; Shi, W.; Smith, N.A.; Luo, J. Promptcap: Prompt-guided image captioning for vqa with gpt-3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 2963–2975. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.; Li, L.; Lin, C.C.; Ahmed, F.; Gan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wang, L. Swinbert: End-to-end transformers with sparse attention for video captioning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 17949–17958. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, X. Graphprompt: Unifying pre-training and downstream tasks for graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; pp. 417–428. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Rossi, L. PHGNN: A Novel Prompted Hypergraph Neural Network to Diagnose Alzheimer’s Disease. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.14577. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Dang, K.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Qwen Technical Report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahroudy, A.; Liu, J.; Ng, T.T.; Wang, G. Ntu rgb+ d: A large scale dataset for 3d human activity analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1010–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Shahroudy, A.; Perez, M.; Wang, G.; Duan, L.Y.; Kot, A.C. Ntu rgb+ d 120: A large-scale benchmark for 3d human activity understanding. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 42, 2684–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Ni, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, Z. Uav-human: A large benchmark for human behavior understanding with unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 16266–16275. [Google Scholar]

- Cafarelli, D.; Ciampi, L.; Vadicamo, L.; Gennaro, C.; Berton, A.; Paterni, M.; Benvenuti, C.; Passera, M.; Falchi, F. MOBDrone: A drone video dataset for man overboard rescue. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Analysis and Processing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 633–644. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Lan, C.; Xing, J.; Zeng, W.; Xue, J.; Zheng, N. View adaptive recurrent neural networks for high performance human action recognition from skeleton data. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2117–2126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Shahroudy, A.; Xu, D.; Wang, G. Spatio-temporal lstm with trust gates for 3d human action recognition. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 816–833. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhong, Q.; Xie, D.; Pu, S. Co-occurrence feature learning from skeleton data for action recognition and detection with hierarchical aggregation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.06055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q. Actional-structural graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3595–3603. [Google Scholar]

- Si, C.; Chen, W.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. An attention enhanced graph convolutional lstm network for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 1227–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Huang, Y.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, L. Part-level graph convolutional network for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 11045–11052. [Google Scholar]

- Alsarhan, T.; Ali, U.; Lu, H. Enhanced discriminative graph convolutional network with adaptive temporal modelling for skeleton-based action recognition. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2022, 216, 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; He, K.; Xu, D. Skeleton-based human action recognition via large-kernel attention graph convolutional network. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2023, 29, 2575–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J. Multi-scale spatial–temporal convolutional neural network for skeleton-based action recognition. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2023, 26, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Geng, P.; Lu, X.; Li, W.; Lyu, L. Skeleton-based action recognition through attention guided heterogeneous graph neural network. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 309, 112868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, C.; Jing, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. Skeleton-based action recognition with spatial reasoning and temporal stack learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, C.; Xu, Y.; Xia, L.; Dai, P.; Bo, L.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y. Traffic flow forecasting with spatial-temporal graph diffusion network. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 15008–15015. [Google Scholar]

- Plizzari, C.; Cannici, M.; Matteucci, M. Spatial temporal transformer network for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 10–15 January 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 694–701. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, M.; Kazi, A.; Baghshah, M.S.; Rabiee, H.R.; Navab, N. RA-GCN: Graph convolutional network for disease prediction problems with imbalanced data. Med Image Anal. 2022, 75, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Chen, W.; Cheng, J.; Lu, H. Skeleton-based action recognition with shift graph convolutional network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Shen, Y.; Ma, L. Msst-rt: Multi-stream spatial-temporal relative transformer for skeleton-based action recognition. Sensors 2021, 21, 5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Lan, C.; Zeng, W.; Lu, C. Skeleton-based mutually assisted interacted object localization and human action recognition. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 25, 4415–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Params (M) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 86.8 | 0.54 |

| +EDR | 87.8 ± 0.07 | 0.55 |

| +MHAG | 86.9 ± 0.12 | 0.89 |

| +MSSP | 87.8 ± 0.07 | 1.68 |

| +MS | 89.4 ± 0.08 | 0.69 |

| MSG-GCN | 90.2 ± 0.11 | 1.88 |

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Params (M) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 86.8 | 0.54 |

| +FI | 87.8 ± 0.05 | 0.56 |

| +JT | 88.7 ± 0.05 | 0.67 |

| +JT+FI | 88.9 ± 0.06 | 0.69 |

| MS (+JT+FI+Text) | 89.4 ± 0.08 | 0.69 |

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Params (M) |

|---|---|---|

| 2-heads | 90.0 ± 0.12 | 1.75 |

| 4-heads | 90.2 ± 0.11 | 1.88 |

| 6-heads | 90.2 ± 0.11 | 2.02 |

| 8-heads | 90.1 ± 0.14 | 2.15 |

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Params (M) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 89.2 ± 0.06 | 0.90 |

| Global | 89.7 ± 0.10 | 0.90 |

| Parts | 89.8 ± 0.13 | 1.23 |

| MSSP (Parts+Global) | 90.2 ± 0.11 | 1.88 |

| Prompt | Text-Encoder | Acc (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Describe [action] briefly; Describe motion of: left hand, right hand, left knee, right knee, head and spine. | BERT | |

| CLIP | ||

| Describe a person performing [action] in natural language; Then describe the movements of: left hand, right hand, left knee, right knee, head and spine. | BERT | |

| CLIP | ||

| Describe a person [action] in details; Describe following body parts actions when [action]: left hand, right hand, left knee, right knee, head and spine. | BERT | |

| CLIP |

| Method | Params (M) | CS (%) | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCN [46] | 1.13 | 86.5 | 91.1 |

| ST-GCN [19] | 3.10 | 81.5 | 88.3 |

| 2s-AGCN [20] | 6.94 | 88.5 | 95.1 |

| AS-GCN [47] | 6.99 | 86.8 | 94.2 |

| AGC-LSTM [48] | 22.89 | 89.2 | 95.0 |

| PL-GCN [49] | 20.70 | 89.2 | 95.0 |

| MS-G3D (joint) [21] | 3.20 | 89.4 | 95.0 |

| MS-G3D [21] | 6.44 | 91.5 | 96.2 |

| CTR-GCN (joint) [22] | 1.46 | 89.9 | 95.0 |

| CTR-GCN [22] | 2.92 | 92.4 | 96.9 |

| ED-GCN (joint) [50] | - | 86.7 | 93.9 |

| ED-GCN [50] | - | 88.7 | 95.2 |

| LKA-GCN (joint) [51] | - | 90.0 | 95.0 |

| LKA-GCN [51] | 3.78 | 90.7 | 96.1 |

| MSSTNet [52] | 39.6 | 89.6 | 95.3 |

| AG-HGNN (joint) [53] | - | 87.6 | 93.2 |

| AG-HGNN [53] | 16.46 | 93.1 | 97.2 |

| MSG-GCN (ours) | 1.88 | 90.2 | 95.6 |

| Method | Params (M) | CS (%) | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ST-GCN [19] | 3.10 | 70.7 | 73.2 |

| SR-TSL [54] | 19.07 | 74.1 | 79.9 |

| 2s-AGCN [20] | 6.94 | 82.5 | 84.2 |

| AS-GCN [47] | 6.99 | 77.7 | 78.9 |

| ST-GDN [55] | - | 80.8 | 82.3 |

| ST-TR [56] | 12.10 | 82.7 | 84.7 |

| RA-GCN [57] | 6.25 | 81.1 | 82.7 |

| MSSTNet (joint & bone) [52] | 39.6 | 83.6 | 84.7 |

| MSSTNet [52] | 39.6 | 85.3 | 86.0 |

| MSG-GCN (ours) | 1.88 | 84.4 | 86.4 |

| Method | Params (M) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ST-GCN [19] | 3.10 | 30.3 |

| 2s-AGCN [20] | 6.94 | 34.8 |

| Shift-GCN [58] | 2.80 | 38.0 |

| MSST-RT [59] | - | 41.2 |

| IO-SGN [60] | - | 40.0 |

| MSSTNet [52] | 39.6 | 43.0 |

| MSG-GCN (ours) | 1.88 | 41.6 |

| Method | Params (M) | GFLOPs | FLOPs/f (M) | Lat. (ms) | FPS | Mem. (MB) | Acc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST-GCN [19] | 3.10 | 16.30 | 34.42 | 4.1 | 244 | 445 | 91.0 |

| 2s-AGCN [20] | 6.94 | 37.32 | 66.74 | 4.6 | 217 | 766 | 94.5 |

| MS-G3D (joint) [21] | 6.44 | 5.22 | 33.13 | 3.9 | 256 | 667 | 94.0 |

| Shift-GCN (joint) [58] | 2.80 | 2.50 | 18.52 | 3.5 | 311 | 310 | 93.7 |

| CTR-GCN (joint) [22] | 1.46 | 19.7 | 49.25 | 4.7 | 212 | 489 | 96.0 |

| MSG-GCN (ours) | 1.88 | 0.31 | 13.65 | 2.6 | 390 | 218 | 96.0 |

| Action | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drowning suspected | 97.2 | 97.0 | 0.971 |

| Swimming | 96.7 | 95.2 | 0.959 |

| Call for help | 95.8 | 97.1 | 0.964 |

| Method | Accuracy at Each Occlusion Level (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 10% | 20% | 30% | |

| ST-GCN [19] | 91.0 | 78.1 | 62.4 | 35.6 |

| 2s-AGCN [20] | 94.5 | 82.4 | 66.8 | 44.5 |

| MS-G3D (joint) [21] | 94.0 | 83.9 | 70.4 | 57.7 |

| Shift-GCN (joint) [58] | 93.7 | 84.0 | 69.3 | 58.9 |

| CTR-GCN (joint) [22] | 96.0 | 86.1 | 74.7 | 60.7 |

| MSG-GCN (ours) | 96.0 | 88.2 | 79.2 | 64.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hang, R.; He, G.; Dong, L. MSG-GCN: Multi-Semantic Guided Graph Convolutional Network for Human Overboard Behavior Recognition in Maritime Drone Systems. Drones 2025, 9, 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110768

Hang R, He G, Dong L. MSG-GCN: Multi-Semantic Guided Graph Convolutional Network for Human Overboard Behavior Recognition in Maritime Drone Systems. Drones. 2025; 9(11):768. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110768

Chicago/Turabian StyleHang, Ruijie, Guiqing He, and Liheng Dong. 2025. "MSG-GCN: Multi-Semantic Guided Graph Convolutional Network for Human Overboard Behavior Recognition in Maritime Drone Systems" Drones 9, no. 11: 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110768

APA StyleHang, R., He, G., & Dong, L. (2025). MSG-GCN: Multi-Semantic Guided Graph Convolutional Network for Human Overboard Behavior Recognition in Maritime Drone Systems. Drones, 9(11), 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110768