Dynamic Analysis of a Family of Iterative Methods with Fifth-Order Convergence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Improved Methods and Convergence Analysis

3. Fundamentals of Analysis

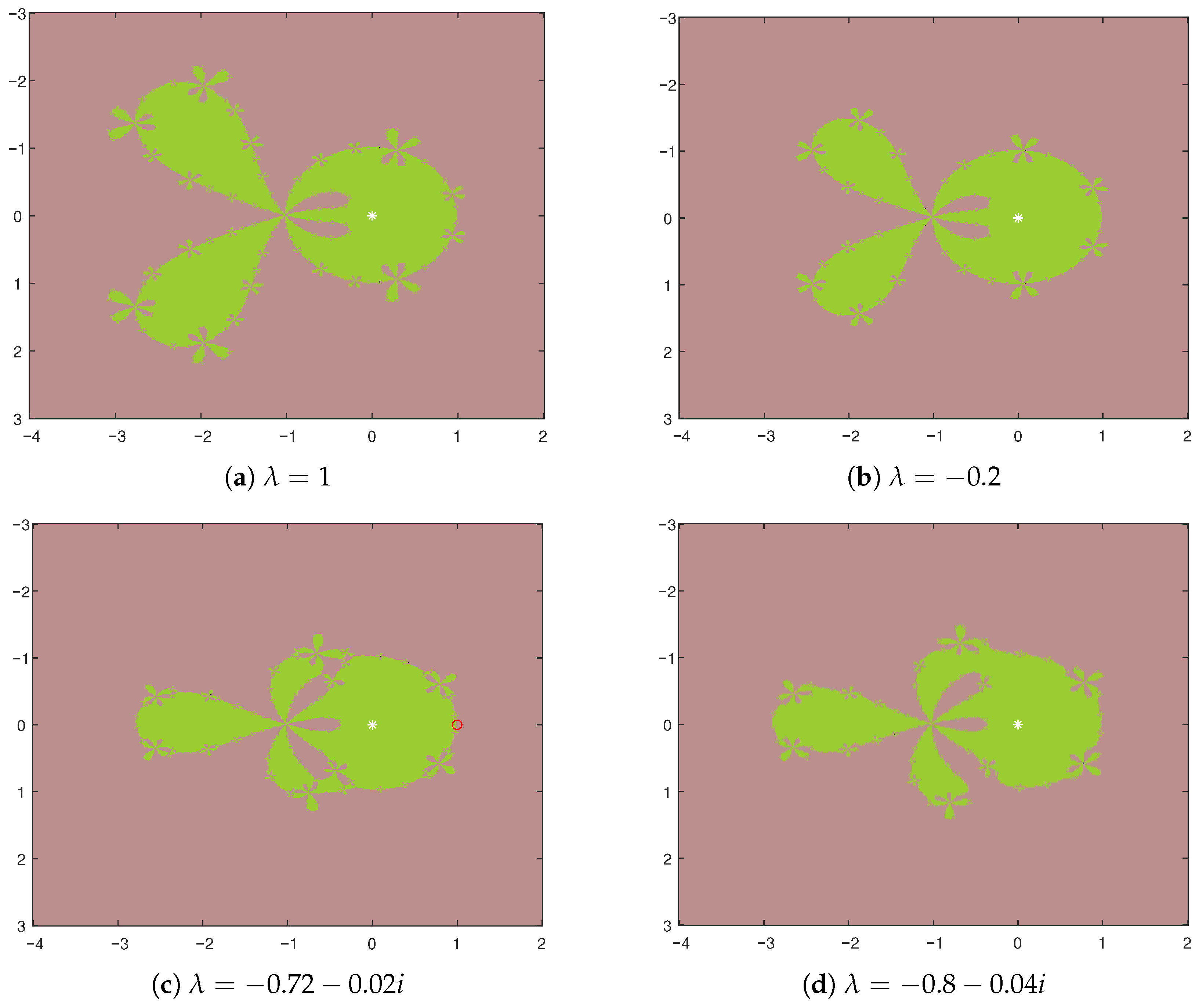

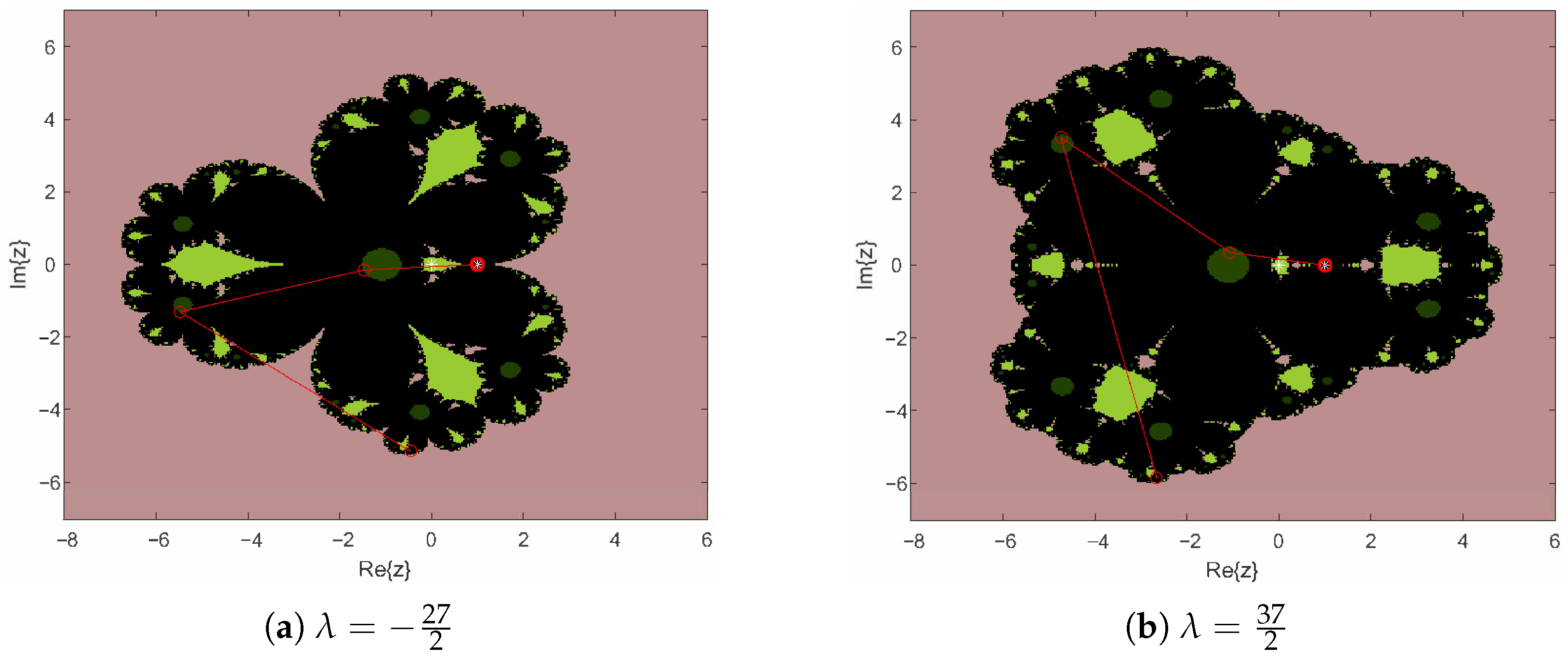

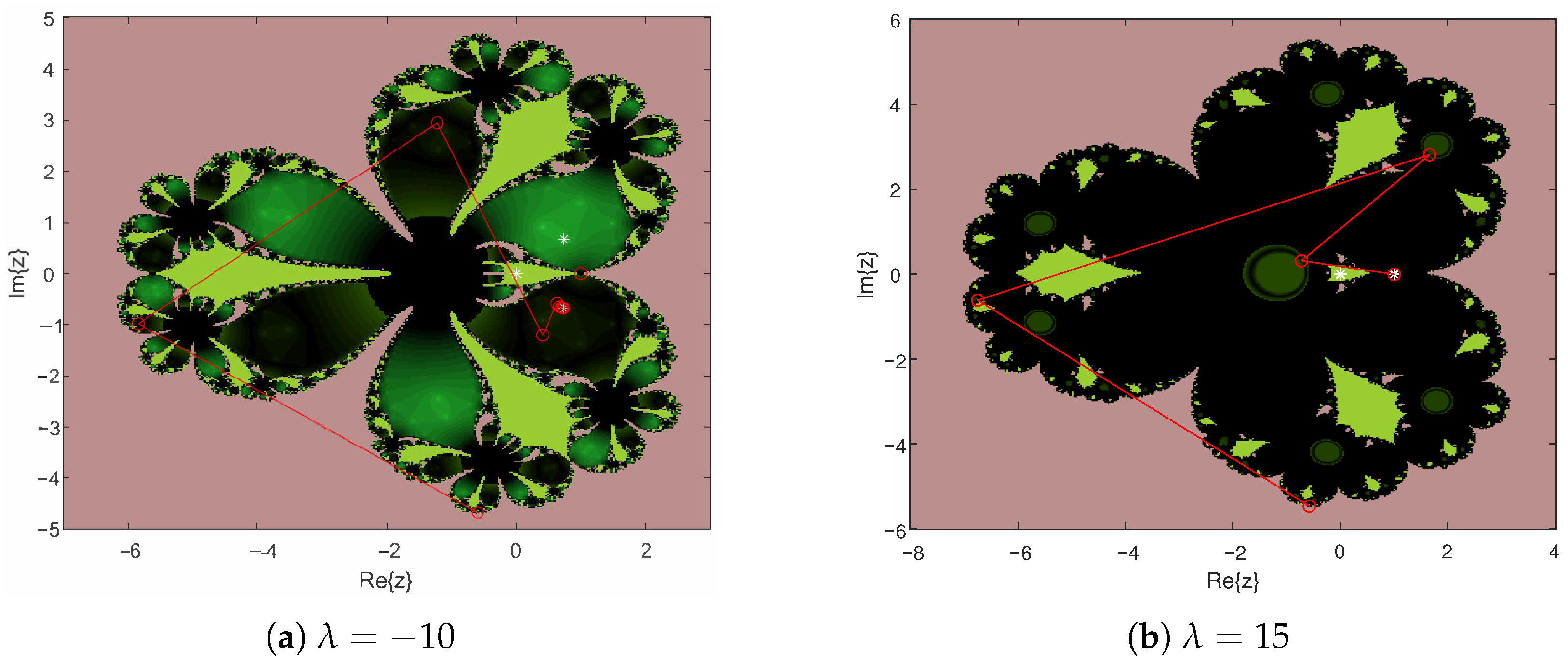

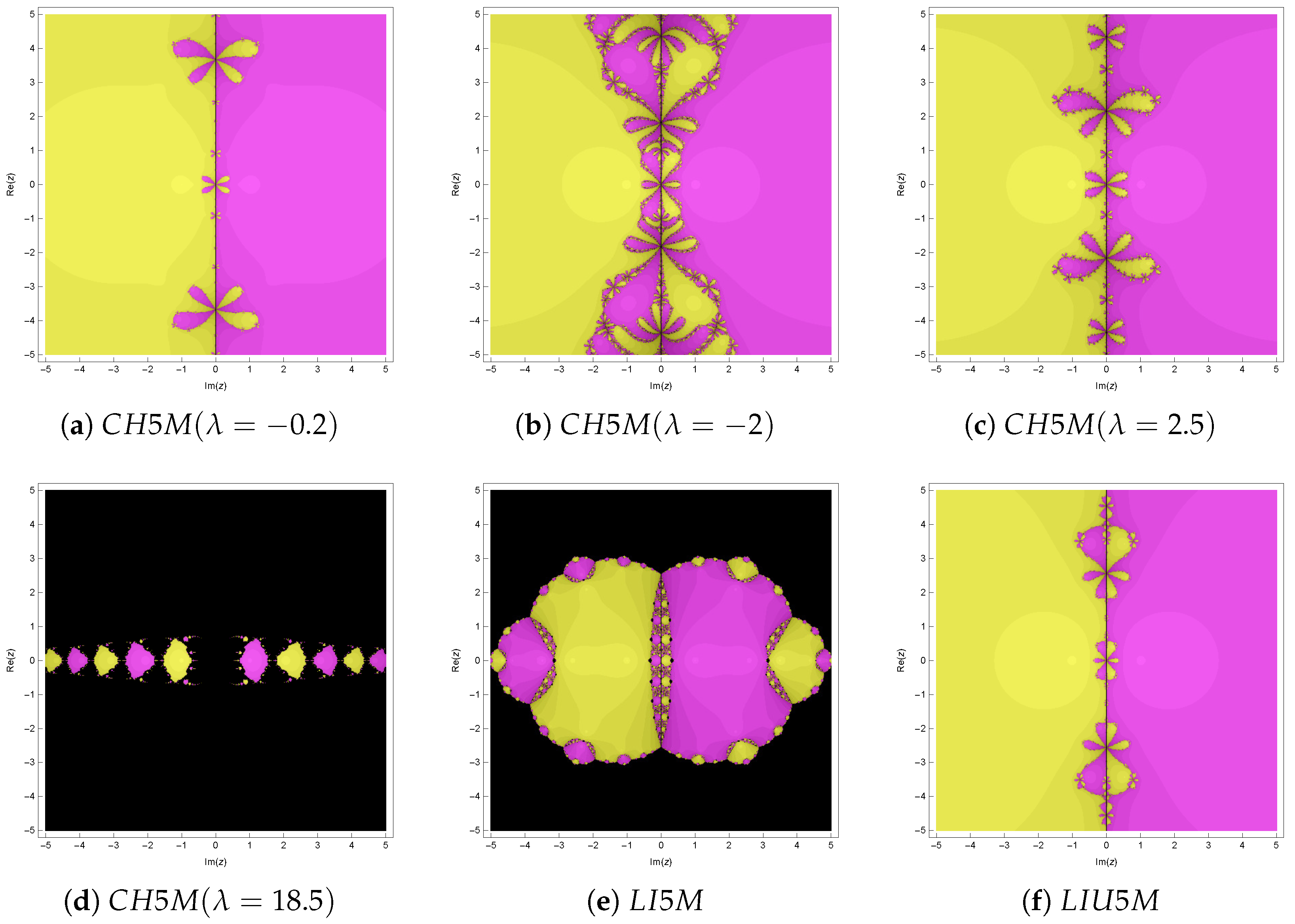

4. Dynamical Analysis

4.1. Fixed Point and Critical Point

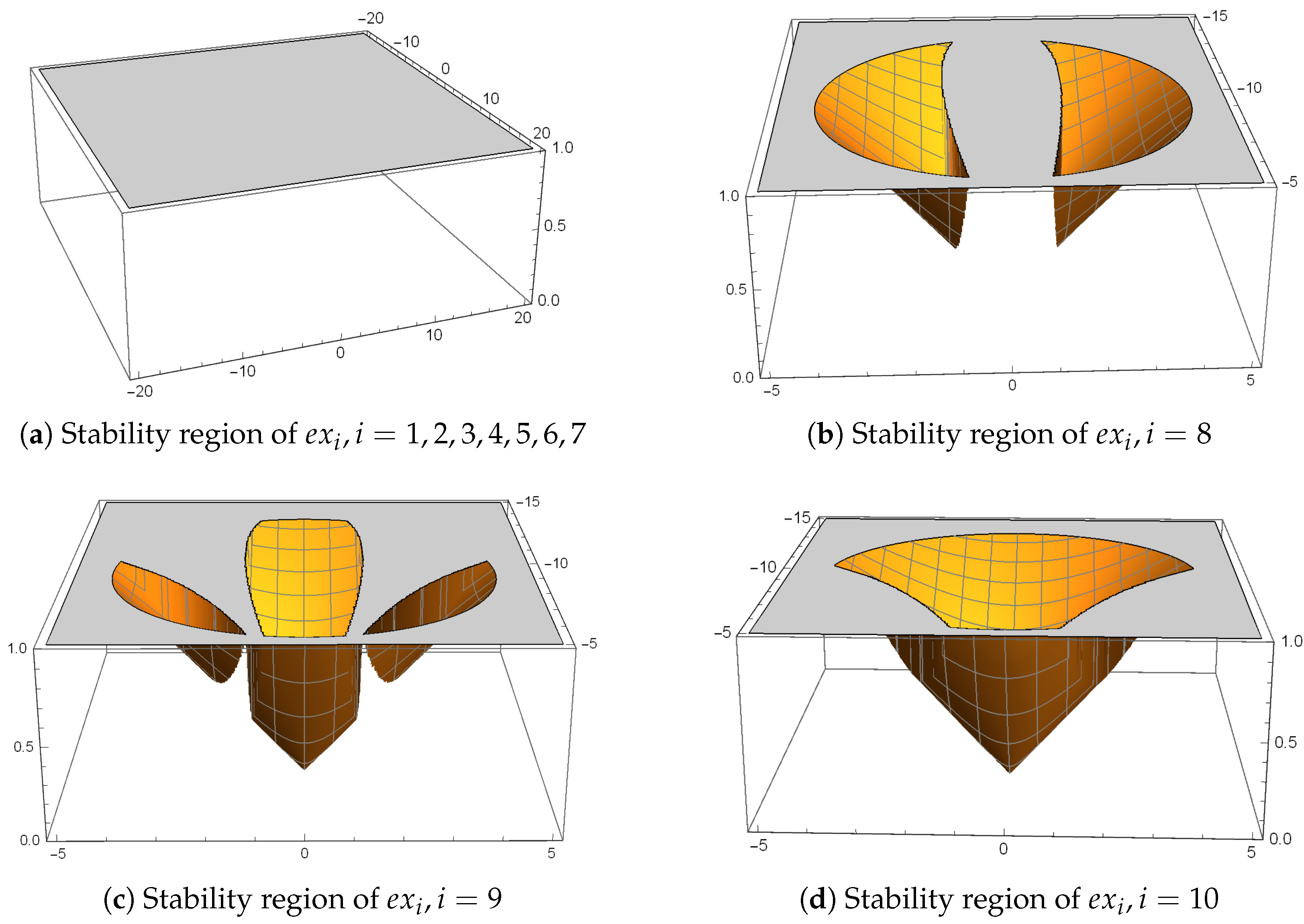

4.1.1. Fixed Point and Its Stability

- If , can be reduced to , and then the operator has seven strange fixed points ,

- If , can be reduced to , and then the operator has nine strange fixed points , , .

- If , is an attractive point;

- If , is a parabolic point;

- If , is a repulsive point.

- are all repulsive points;

- are attractive points in the yellow area of Figure 2.

4.1.2. Critical Point of Operator

- If , has three free critical points ;

- If , has two free critical points ;

- If , has three free critical points ;

- If , has three free critical points .

4.2. Parameter Spaces and Dynamic Planes

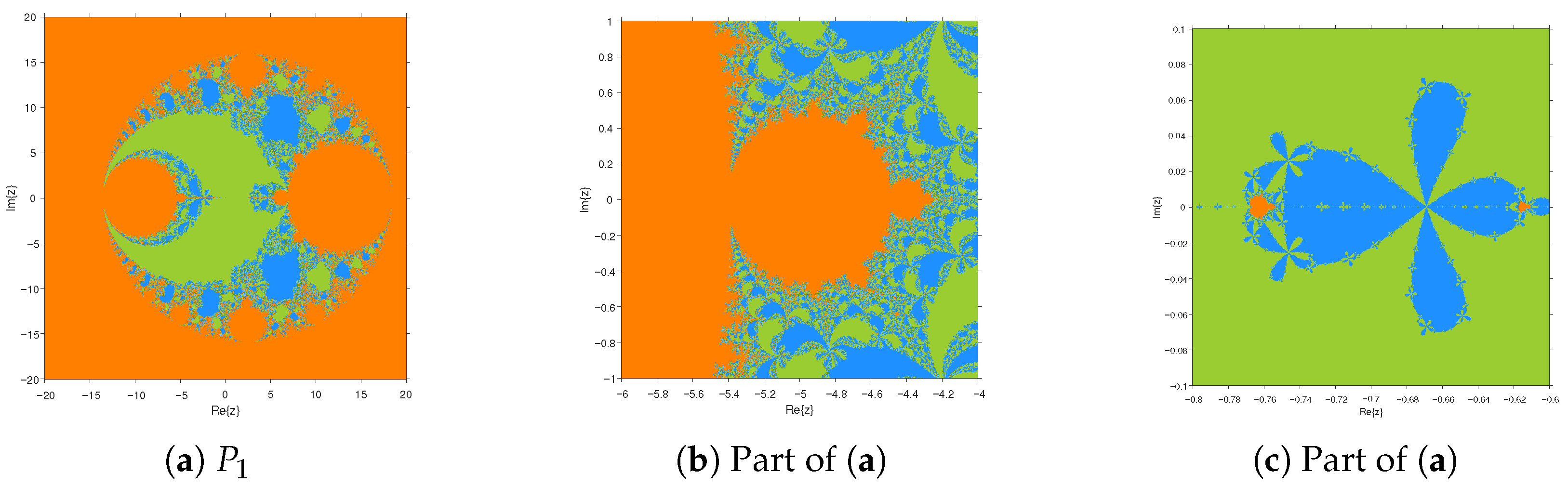

4.2.1. Parameter Space

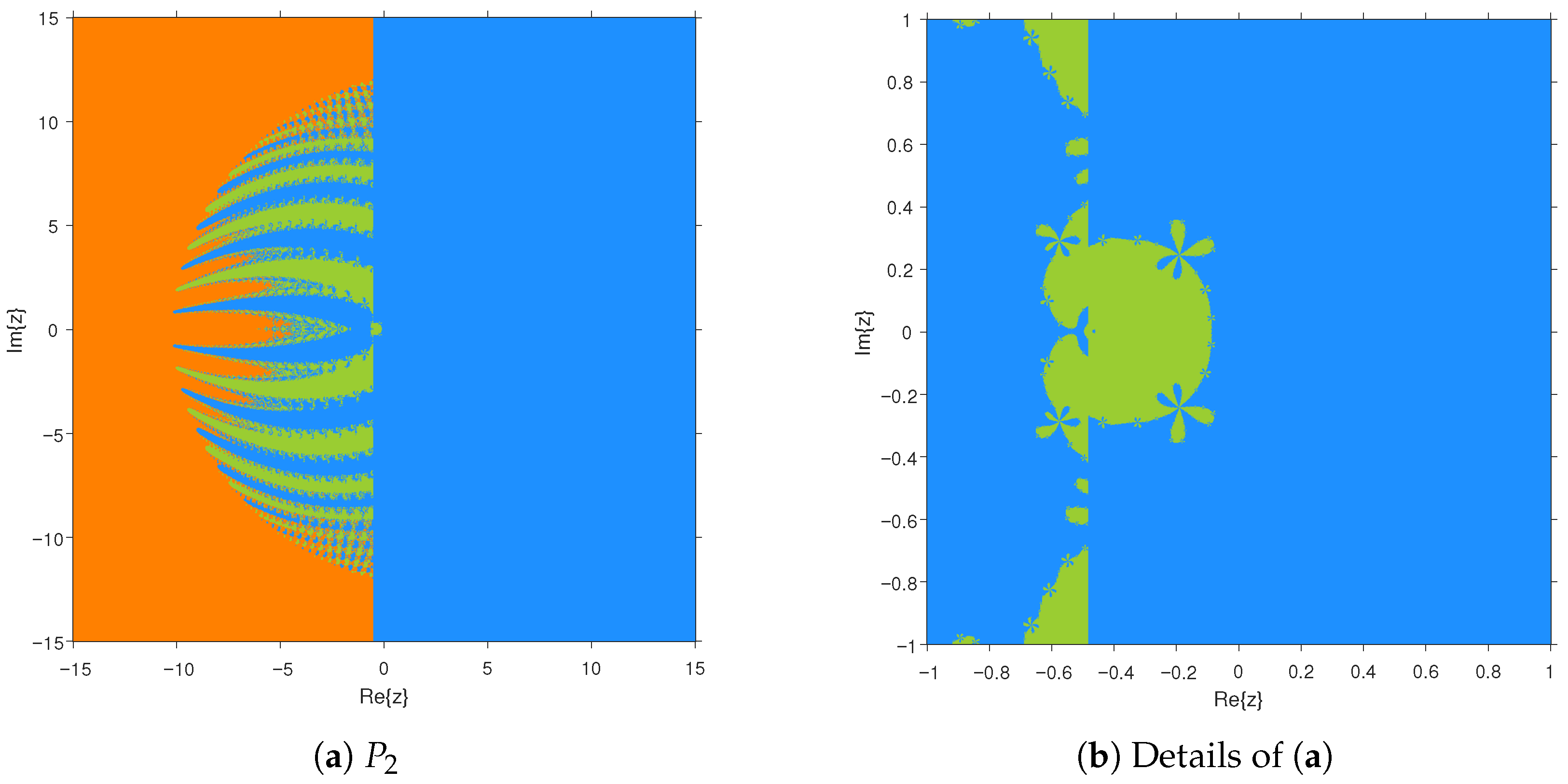

4.2.2. Dynamic Planes

5. Comparison of Fractal Diagrams for Different Methods

6. Numerical Results

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Aizenman, M. Fractals: Form, Chance, and Dimension. Phys. Today 1979, 32, 65–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, M.; Nagahama, H. Informative fractal dimension associated with nonmetricity in information geometry. Phys. A 2023, 625, 129017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, C.; Deng, Y.; Cheong, K.H. Information fractal dimension of mass function. Fractals 2022, 30, 2250110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, T.; Shen, J.; Hu, Z. Fractal design of microfluidics and nanofluidics—A review. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2016, 155, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, N. Fractal geometry in the arts: An overview across the different cultures. Pattern Recognit. 2004, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Peitgen, H.; Richter, P. The Beauty of Fractals; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, H. On the dynamics of entire functions on the Julia set. Results Math. 1996, 30, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letherman, S.D.; Wood, R.M.W. A note on the Julia set of a rational function. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1995, 118, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Yang, C.C. Fatou Components and a Problem of Bergweiler. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos Appl. Sci. Eng. 1998, 8, 1613–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, A.; Jaiswal, J.P.; Torregrosa, J.R. Stability analysis of fourth-order iterative method for finding multiple roots of non-linear equations. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2019, 4, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, R.; Cordero, A.; Motsa, S.S.; Torregrosa, J.R. On optimal fourth-order optimal families of methods for multiple roots and their dynamics. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 265, 520–532. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X. An extension of high-order Kou’s method for solving nonlinear systems and its stability analysis. Electron. Res. Arch. 2025, 33, 1566–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, X.F. A single parameter fourth-order Jarrat-type iterative method for solving nonlinear systems. AIMS Math. 2025, 10, 7847–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Kim, Y.I. The dynamical analysis of a uniparametric family of three-point optimal eighth-order multiple-root finders under the Möbius conjugacy map on the Riemann sphere. Numer. Algorithms 2020, 83, 1063–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicharro, F.I.; Cordero, A.; Torregrosa, J.R. Drawing dynamical and parameters planes of iterative families and methods. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 780153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.F.; Li, W.S. Fractal behavior of king’s optimal eighth-order iterative method and its numerical application. Math. Commun. 2024, 29, 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila, R.R.; Cordero, A.; Torregrosa, J.R. Isonormal surfaces: A new tool for the multi-dimensional dynamical analysis of iterative methods for solving nonlinear systems. Math. Meth. Appl. Sci. 2022, 45, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, B.; Cordero, A.; Torregrosa, J.R.; Vindel, P. Dynamical analysis of an iterative method with memory on a family of third-degree polynomials. AIMS Math. 2022, 7, 6445–6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, A.; Segura, E.; Torregrosa, J.R.; Vassileva, M.P. Inverse matrix estimations by iterative methods with weight functions and their stability analysis. Appl. Math. Lett. 2024, 155, 109122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicharro, F.I.; Cordero, A.; Garrido, N.; Torregrosa, J.R. On the effect of the multidimensional weight functions on the stability of iterative processes. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2022, 405, 113052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscoso-Martínez, M.; Chicharro, F.I.; Cordero, A.; Torregrosa, J.R.; Ureña-Callay, G. Achieving Optimal Order in a Novel Family of Numerical Methods: Insights from Convergence and Dynamical Analysis Results. Axioms 2024, 13, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Efficient n-point iterative methods with memory for solving nonlinear equations. Numer. Algorithms 2015, 70, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarratt, P. Some fourth order multipoint iterative methods for solving equations. Math. Comput. 1966, 20, 434–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, A.M. Solution of Equations in Euclidean and Banach Spaces; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, N.; Wang, X.F.; Wang, Y. Local convergence analysis of a novel Kurchatov-type derivative-free methods with and without memory for solving nonlinear systems. Int. J. Comput. Methods 2026, 23, 2550033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. An Ostrowski-type method with memory using a novel self-accelerating parameter. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2018, 330, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, V.; Marquina, A. Recurrence relations for rational cubic methods II: The Chebyshev method. Computing 1991, 45, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alefeld, G. On the convergence of Halley’s Method. Am. Math. Mon. 1981, 88, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Argyros, I.K.; Qian, Q. A local convergence theorem for the super-Halley method in a Banach space. Appl. Math. Lett. 1994, 7, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.M.; Hernández, M.A. A family of Chebyshev-Halley type methods in Banach spaces. Bull. Aust. Math. Soc. 1997, 55, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, A.M. Solution of Equation and Systems of Equations; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Liu, P.; Kou, J. An improvement of Chebyshev–Halley methods free from second derivative. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 235, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiullah, M. A fifth-order iterative method for solving nonlinear equations. Numer. Anal. Appl. 2021, 4, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, A.; Gomez, E.; Torregrosa, J.R. Efficient high-order iterative methods for solving nonlinear systems and their application on heat conduction problems. Complexity 2017, 2017, 6457532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Qureshi, S.; Argyros, I.K.; Chicharro, F.I.; Soomro, A. A modified two-step optimal iterative method for solving nonlinear models in one and higher dimensions. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 229, 448–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

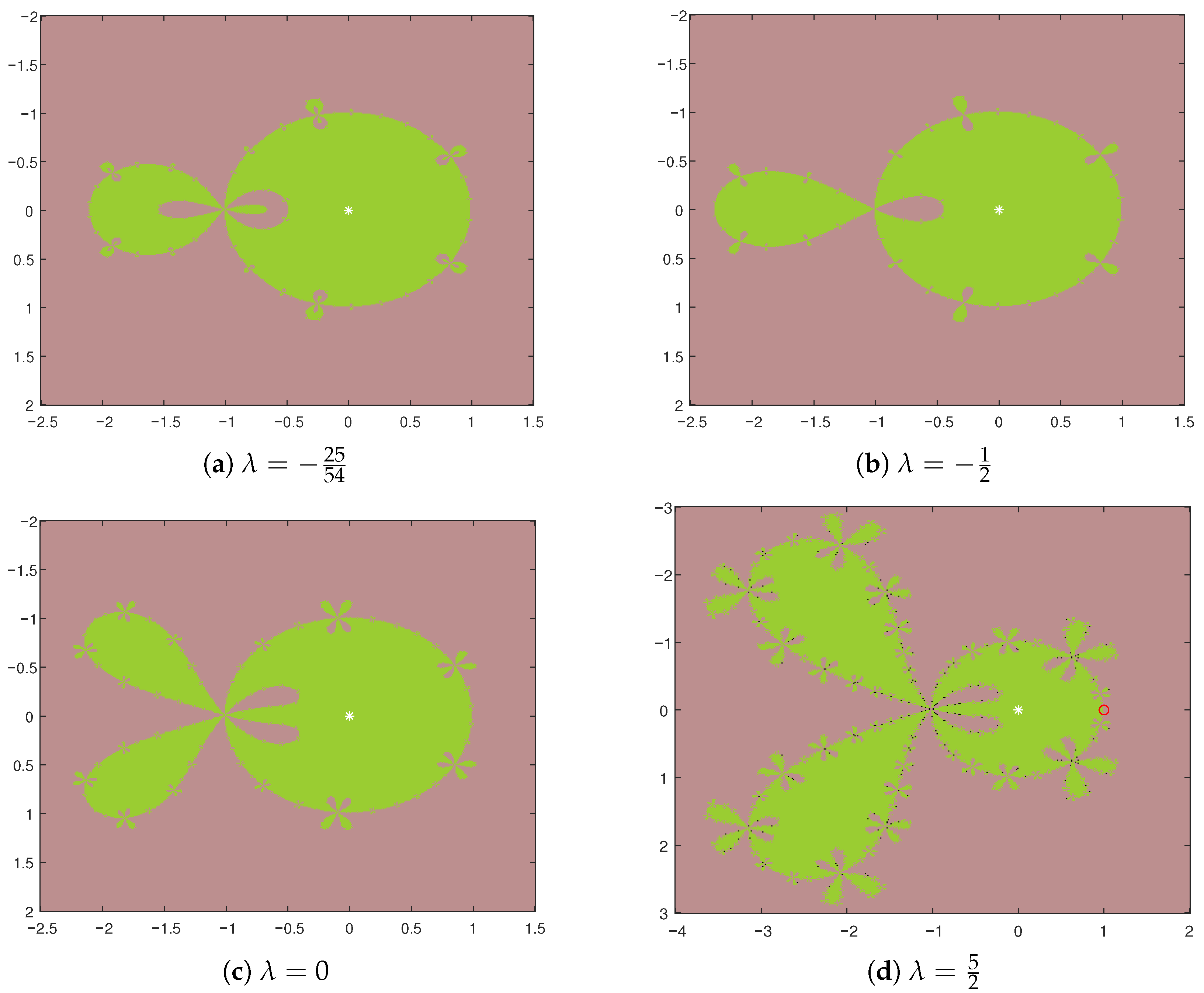

| EI | ACOC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.1 | 0.054435 | 1.041 × 10−8 | 1.8915 × 10−42 | 3.746 × 10−211 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.1 | 2.1 | 0.054435 | 4.3176 × 10−10 | 4.643 × 10−50 | 6.6767 × 10−250 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| 2.1 | 0.054435 | 4.1688 × 10−8 | 9.7406 × 10−39 | 6.7832 × 10−192 | 1.495 | 5.0 | ||

| 0 | 2.2 | 0.045565 | 2.1689 × 10−9 | 7.4262 × 10−46 | 3.4944 × 10−228 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.1 | 2.2 | 0.045565 | 1.1265 × 10−9 | 5.6142 × 10−48 | 1.7258 × 10−239 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| 2.2 | 0.045565 | 1.3786 × 10−8 | 3.8515 × 10−41 | 6.5567 × 10−204 | 1.495 | 5.0 | ||

| 0 | 1.3 | 0.06523 | 2.2322 × 10−8 | 6.0964 × 10−41 | 9.2642 × 10−204 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.1 | 1.3 | 0.06523 | 2.0084 × 10−9 | 2.1124 × 10−46 | 2.719 × 10−231 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| 1.3 | 0.06523 | 1.0889 × 10−7 | 1.1683 × 10−36 | 1.6615 × 10−181 | 1.495 | 5.0 | ||

| 0 | 1.4 | 0.04247 | 5.1534 × 10−10 | 9.5535 × 10−50 | 2.0917 × 10−248 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.1 | 1.4 | 0.03477 | 4.2257 × 10−10 | 8.7093 × 10−50 | 3.2391 × 10−248 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| 1.4 | 0.03477 | 3.523 × 10−9 | 4.1422 × 10−44 | 9.3071 × 10−219 | 1.495 | 5.0 | ||

| 0 | 1.5 | 0.025994 | 9.2855 × 10−9 | 4.0688 × 10−41 | 6.5737 × 10−203 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.1 | 1.5 | 0.025994 | 1.6364 × 10−9 | 8.368 × 10−47 | 2.9262 × 10−233 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| 1.5 | 0.025994 | 3.0454 × 10−8 | 6.0831 × 10−38 | 1.9343 × 10−186 | 1.495 | 5.0 | ||

| 0 | 1.6 | 0.074006 | 4.1994 × 10−7 | 7.6987 × 10−33 | 1.5942 × 10−161 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.1 | 1.6 | 0.074007 | 5.3893 × 10−7 | 3.2434 × 10−34 | 2.5599 × 10−170 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| 1.6 | 0.07401 | 3.9657 × 10−6 | 2.2776 × 10−27 | 1.4233 × 10−133 | 1.495 | 5.0 | ||

| 0 | 1.4 | 0.0044916 | 5.1534 × 10−10 | 9.5535 × 10−50 | 2.0917 × 10−248 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.1 | 1.4 | 0.0044916 | 7.38 × 10−14 | 9.0937 × 10−68 | 2.5832 × 10−337 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| 1.4 | 0.0044916 | 4.9068 × 10−14 | 6.5608 × 10−69 | 2.8039 × 10−343 | 1.495 | 5.0 | ||

| 0 | 1.5 | 0.04247 | 5.1534 × 10−10 | 9.5535 × 10−50 | 2.0917 × 10−248 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.1 | 1.5 | 0.095509 | 2.9334 × 10−7 | 9.0214 × 10−35 | 2.4821 × 10−172 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| 1.5 | 0.095508 | 1.2215 × 10−7 | 6.2732 × 10−37 | 2.2408 × 10−183 | 1.495 | 5.0 | ||

| 0 | −0.4 | 0.042854 | 3.2432 × 10−8 | 9.4964 × 10−39 | 2.0441 × 10−191 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.1 | −0.4 | 0.042854 | 8.7359 × 10−9 | 4.693 × 10−42 | 2.0998 × 10−208 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.4 | 0.042854 | 8.3083 × 10−8 | 2.3652 × 10−36 | 4.4222 × 10−179 | 1.495 | 5.0 | ||

| 0 | −0.5 | 0.057145 | 1.9746 × 10−7 | 7.9457 × 10−35 | 8.3822 × 10−172 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.1 | −0.5 | 0.057146 | 8.5069 × 10−8 | 4.1094 × 10−37 | 1.081 × 10−183 | 1.495 | 5.0 | |

| −0.5 | 0.057146 | 3.8502 × 10−7 | 5.0553 × 10−33 | 1.9727 × 10−162 | 1.495 | 5.0 |

| Methed | EI | Time | ACOC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH5M | 2.1 | 0.054435 | 9.7672 × 10−9 | 1.9254 × 10−42 | 5.7317 × 10−211 | 1.495 | 0.859375 | 5.0 | |

| LI5M | 2.1 | 0.054435 | 1.1860 × 10−8 | 7.2608 × 10−42 | 6.2445 × 10−208 | 1.495 | 0.984375 | 5.0 | |

| LIU5M | 2.1 | 0.054435 | 1.0285 × 10−7 | 2.1370 × 10−36 | 8.2752 × 10−180 | 1.380 | 0.953125 | 5.0 | |

| CH5M | 2.2 | 0.045565 | 4.3697 × 10−9 | 3.4509 × 10−44 | 1.06 × 10−219 | 1.495 | 0.859375 | 5.0 | |

| LI5M | 2.2 | 0.045565 | 7.1280 × 10−9 | 5.6938 × 10−43 | 1.8518 × 10−213 | 1.495 | 0.953125 | 5.0 | |

| LIU5M | 2.2 | 0.045565 | 3.2342 × 10−8 | 6.5699 × 10−39 | 2.2725 × 10−192 | 1.380 | 0.875000 | 5.0 | |

| CH5M | 1.3 | 0.06523 | 2.7294 × 10−8 | 3.6249 × 10−40 | 1.4976 × 10−199 | 1.495 | 1 | 5.0 | |

| LI5M | 1.3 | 0.06523 | 2.3825 × 10−8 | 2.2347 × 10−40 | 1.6224 × 10−200 | 1.495 | 1.06250 | 5.0 | |

| LIU5M | 1.3 | 0.06523 | 3.3406 × 10−7 | 9.6132 × 10−34 | 1.897 × 10−166 | 1.380 | 1.062500 | 5.0 | |

| CH5M | 1.4 | 0.03477 | 1.2182 × 10−9 | 6.4193 × 10−47 | 2.6083 × 10−233 | 1.495 | 0.96875 | 5.0 | |

| LI5M | 1.4 | 0.03477 | 1.7212 × 10−9 | 4.3970 × 10−46 | 4.7842 × 10−229 | 1.495 | 1.078125 | 5.0 | |

| LIU5M | 1.4 | 0.03477 | 1.7212 × 10−9 | 3.0664 × 10−41 | 6.2639 × 10−204 | 1.380 | 1.015625 | 5.0 | |

| CH5M | 1.5 | 0.025994 | 6.1621 × 10−9 | 5.1104 × 10−42 | 2.005 × 10−207 | 1.495 | 2.15625 | 5.0 | |

| LI5M | 1.5 | 0.025994 | 9.2354 × 10−9 | 6.5207 × 10−41 | 1.1442 × 10−201 | 1.495 | 2.84375 | 5.0 | |

| LIU5M | 1.5 | 0.025994 | 6.6011 × 10−8 | 6.0088 × 10−36 | 3.7554 × 10−176 | 1.380 | 2.421875 | 5.0 | |

| CH5M | 1.6 | 0.074008 | 1.4569 × 10−6 | 3.7752 × 10−30 | 4.4111 × 10−148 | 1.495 | 2.218750 | 5.0 | |

| LI5M | 1.6 | 0.074002 | 3.6376 × 10−6 | 6.1819 × 10−28 | 8.7625 × 10−137 | 1.495 | 3 | 5.0 | |

| LIU5M | 1.6 | 0.073999 | 7.1484 × 10−6 | 8.9483 × 10−26 | 2.7505 × 10−125 | 1.380 | 2.328125 | 5.0 | |

| CH5M | 1.4 | 0.0044916 | 1.9748 × 10−13 | 3.1876 × 10−65 | 3.4933 × 10−324 | 1.495 | 5.78125 | 5.0 | |

| LI5M | 1.4 | 0.0044916 | 1.8885 × 10−13 | 2.5866 × 10−65 | 1.2466 × 10−324 | 1.495 | 5.9375 | 5.0 | |

| LIU5M | 1.4 | 0.0044916 | 2.8232 × 10−12 | 2.7044 × 10−58 | 2.1813 × 10−288 | 1.380 | 9.09375 | 5.0 | |

| CH5M | 1.5 | 0.095509 | 4.3341 × 10−7 | 1.6232 × 10−33 | 1.196 × 10−165 | 1.495 | 5.53125 | 5.0 | |

| LI5M | 1.5 | 0.095507 | 0.14697 × 10−6 | 7.3846 × 10−31 | 2.3645 × 10−152 | 1.495 | 5.96875 | 5.0 | |

| LIU5M | 1.5 | 0.095501 | 7.3653 × 10−6 | 3.2682 × 10−26 | 5.6221 × 10−128 | 1.380 | 8.953125 | 5.0 | |

| CH5M | −0.4 | 0.042854 | 1.4664 × 10−8 | 5.4363 × 10−41 | 3.8072 × 10−203 | 1.495 | 2.234375 | 5.0 | |

| LI5M | −0.4 | 0.042854 | 5.1687 × 10−8 | 1.0601 × 10−37 | 3.8484 × 10−186 | 1.495 | 2.734375 | 5.0 | |

| LIU5M | −0.4 | 0.042854 | 1.1932 × 10−7 | 2.2641 × 10−35 | 5.5691 × 10−174 | 1.380 | 2.296875 | 5.0 | |

| CH5M | −0.5 | 0.057146 | 2.9376 × 10−8 | 1.7542 × 10−39 | 1.332 × 10−195 | 1.495 | 2.265625 | 5.0 | |

| LI5M | −0.5 | 0.057145 | 1.2954 × 10−7 | 1.0481 × 10−35 | 3.6347 × 10−176 | 1.495 | 2.703125 | 5.0 | |

| LIU5M | −0.5 | 0.057145 | 6.7844 × 10−7 | 1.3455 × 10−31 | 4.1285 × 10−155 | 1.380 | 2.328125 | 5.0 |

| Methed | EI | Time | ACOC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH5M | 2 | 0.29216 × 10−1 | 0.13939 × 10−7 | 0.34584 × 10−39 | 0.32520 × 10−197 | 1.495 | 1.109375 | 5.0 |

| LI5M | 2 | 0.29216 × 10−1 | 0.22409 × 10−7 | 0.45219 × 10−38 | 0.15130 × 10−191 | 1.495 | 1.218750 | 5.0 |

| LIU5M | 2 | 0.29216 × 10−1 | 0.11075 × 10−6 | 0.10565 × 10−33 | 0.83462 × 10−169 | 1.380 | 1.125000 | 5.0 |

| CH5M | 2.3 | 0.33057 | 0.33057 | 0.30071 × 10−14 | 0.16162 × 10−72 | 1.495 | 1.109375 | 5.0 |

| LI5M | 2.3 | 0.29840 | 0.30819 × 10−1 | 0.29663 × 10−7 | 0.18378 × 10−37 | 1.495 | 1.265625 | 5.0 |

| LIU5M | 2.3 | 0.32531 | 0.39098 × 10−2 | 0.56386 × 10−11 | 0.36141 × 10−55 | 1.380 | 1.203125 | 5.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Guo, S. Dynamic Analysis of a Family of Iterative Methods with Fifth-Order Convergence. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120783

Wang X, Guo S. Dynamic Analysis of a Family of Iterative Methods with Fifth-Order Convergence. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):783. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120783

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaofeng, and Shaonan Guo. 2025. "Dynamic Analysis of a Family of Iterative Methods with Fifth-Order Convergence" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120783

APA StyleWang, X., & Guo, S. (2025). Dynamic Analysis of a Family of Iterative Methods with Fifth-Order Convergence. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120783