Fractal and CT Analysis of Water-Bearing Coal–Rock Composites Under True Triaxial Loading–Unloading

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Apparatus and Scheme

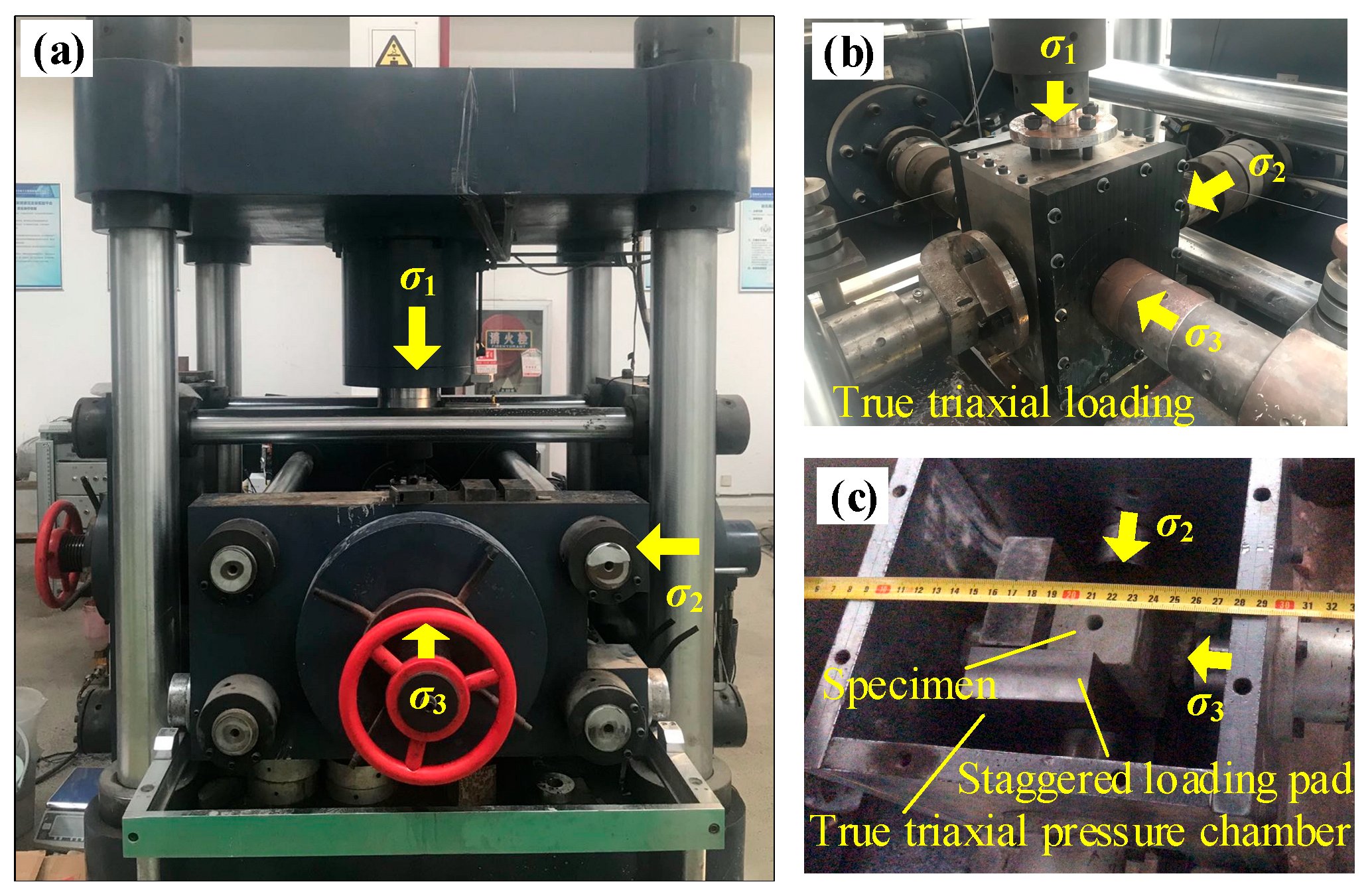

2.1. True Triaxial Local Unloading Test System for Coal–Rock Composite Specimens

2.1.1. Construction of the True Triaxial Stress Model for Coal–Rock Composites

2.1.2. True Triaxial Loading Test System

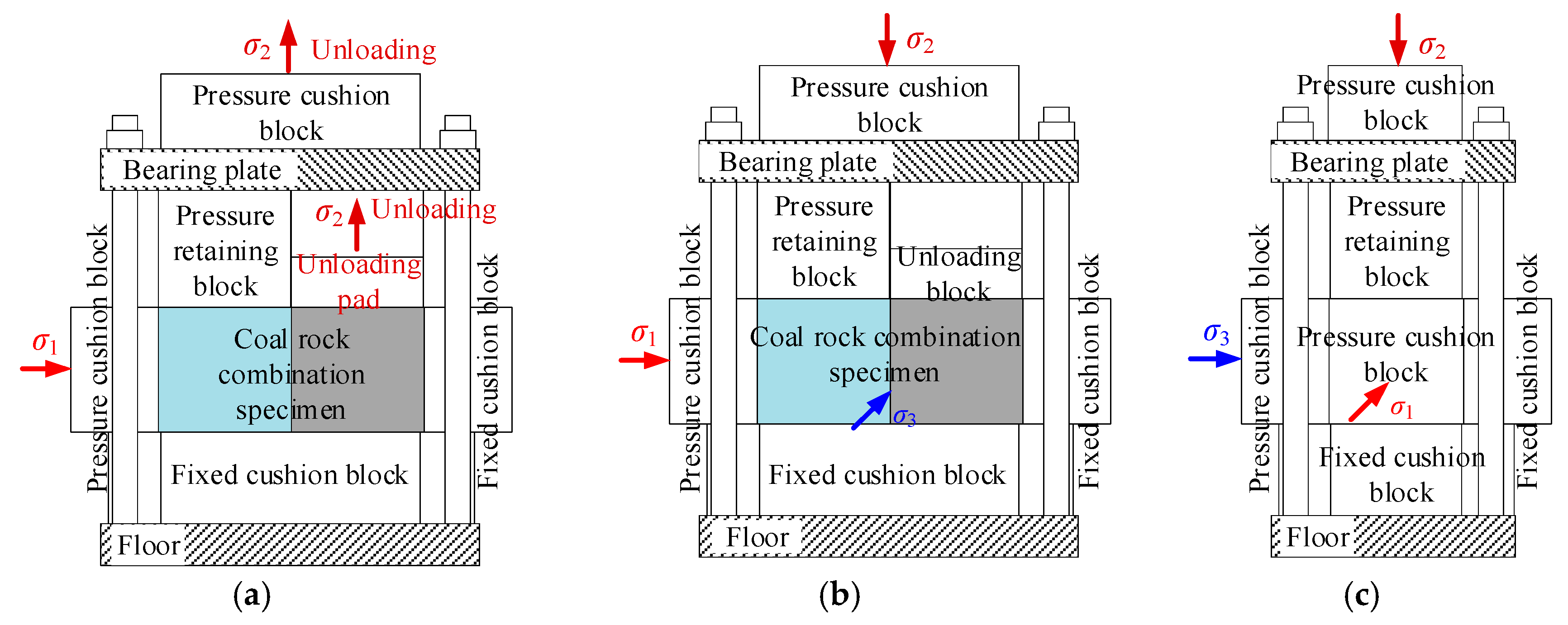

2.1.3. True Triaxial Local Unloading Test Device

- (1)

- Place the true triaxial local unloading testing apparatus, containing the specimen, at the center of the loading mechanism. Ensure that the fixed blocks and pressure-applying blocks are in contact with the passive and active end platens of the triaxial testing machine, respectively. Apply the initial stress in all three directions of the coal–rock specimen at a predetermined loading rate.

- (2)

- Tighten the pressure-retaining nuts and unload along the σ2 direction at the designed rate. The pressure-retaining blocks are constrained by the bearing plates and cannot move, thus maintaining constant pressure on the specimen, while the unloading blocks are flexibly connected to the bearing plates to achieve synchronous unloading.

- (3)

- Upon completion of the test, release the stress in all three directions, loosen the pressure-retaining nuts, and remove the specimen.

2.2. Specimen Preparation and Experimental Scheme

2.2.1. Specimen Preparation

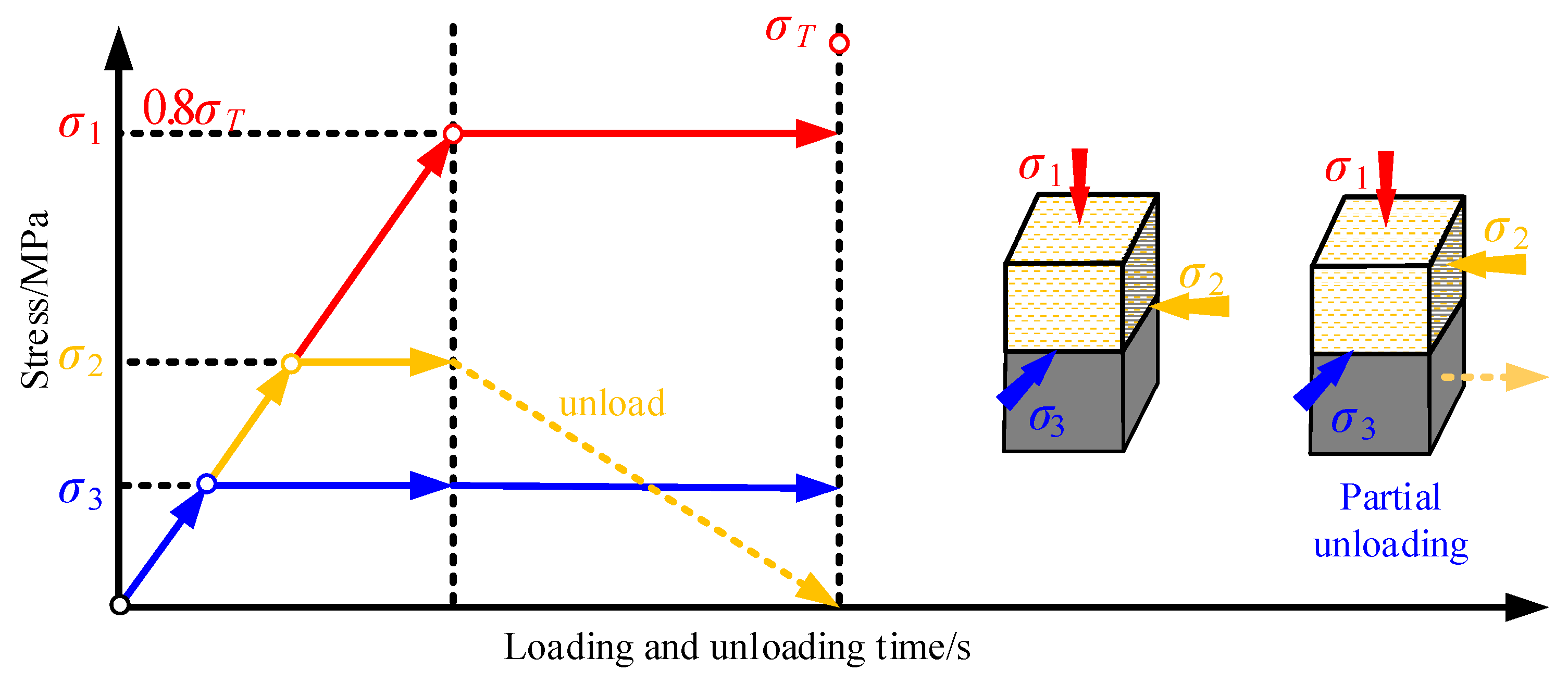

2.2.2. Experimental Scheme

- Apply axial stress σ1 and horizontal stresses σ2 and σ3 simultaneously to the target values (σ1 > σ2 > σ3), and reset displacements in all directions to zero.

- Increase axial stress σ1 to 0.8σT and maintain it constant (σT is the triaxial compressive strength of the coal specimen).

- Keep stresses in the σ1 and σ3 directions constant, and unload the σ2 stress to zero using the local unloading testing apparatus at a loading–unloading rate of 0.1 MPa/s. The rate of 0.1 MPa/s was chosen to simulate quasi-static excavation processes, consistent with typical mining-induced stress adjustments.

- Since coal is the primary material undergoing failure within the coal–rock composite specimens, only the coal portion of the composite was subjected to CT scanning and analysis to investigate the development of internal microfractures.

2.3. CT Scanning

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

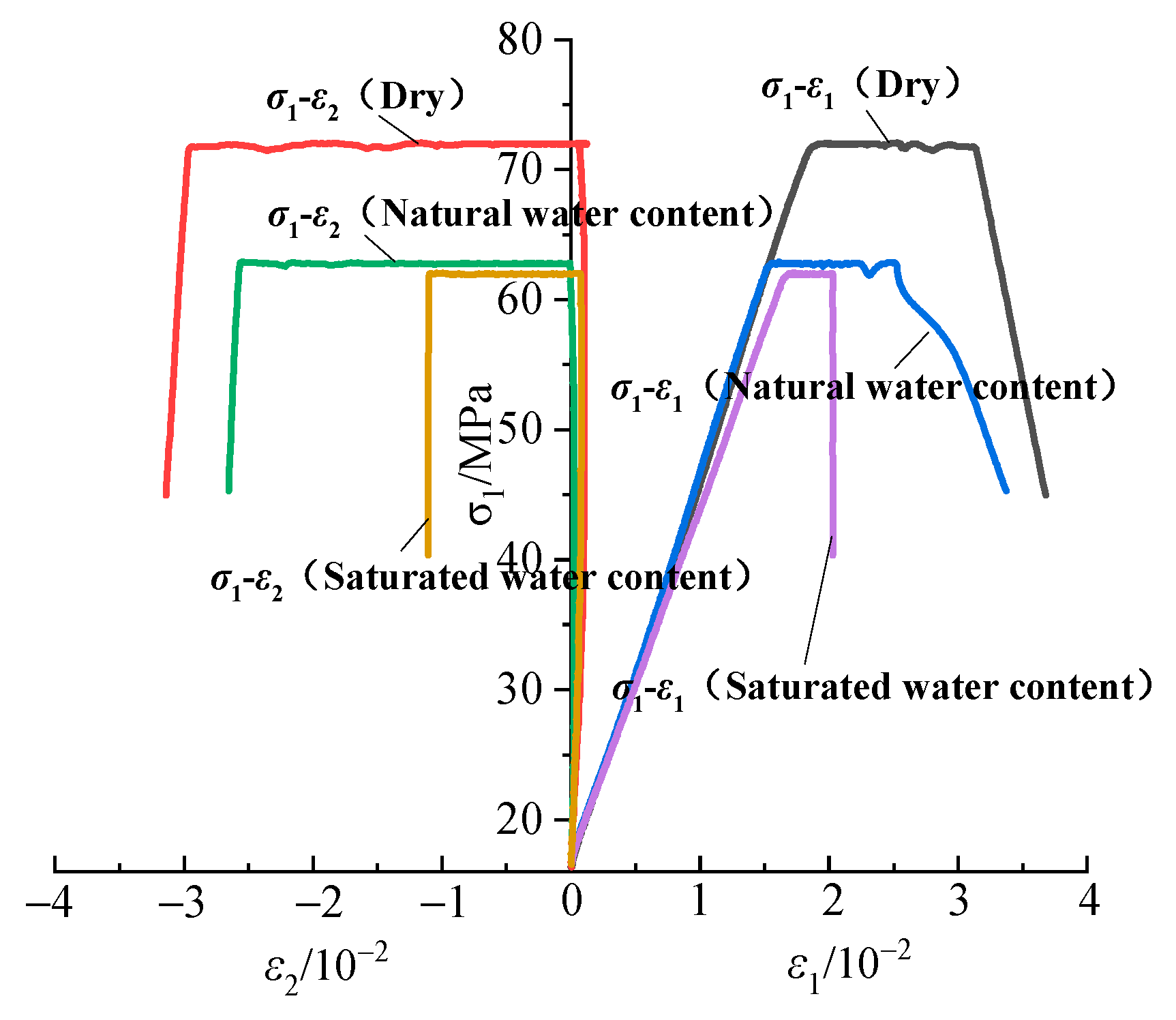

3.1. Mechanical Behavior of Coal–Rock Composite Specimens Under True Triaxial Loading

3.2. 3D Reconstruction and Parameter Characterization of CT Images

3.3. Fracture Characteristics Based on Fractal Theory

- (1)

- Cover the target image with a grid of squares with side length r;

- (2)

- Count the number of squares N(r) that contain fracture pixels;

- (3)

- Vary the square size r and record the corresponding N(r);

- (4)

- If the fracture structure exhibits fractal characteristics, then:

- (1)

- CM1 Coal Specimen (XY, XZ, YZ Directions)

- (2)

- CM2 Coal Specimen (XY, XZ, YZ Directions)

- (3)

- CM3 Coal Specimen (XY, XZ, YZ Directions)

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under the stress path of constant axial stress and unloading of confining stress, the axial strains of the three specimens (CM1, CM2, and CM3) were 0.03678, 0.03371, and 0.02028, respectively, while the lateral strains were 0.0314, 0.02655, and 0.01107, respectively. This indicates that as the rock’s water content increases from dry, natural to saturated states, the deformability of the specimens at failure progressively decreases. The failure mode evolves from shear failure to tensile-shear composite failure and ultimately to tensile failure, reflecting that rocks with higher water content possess lower elastic moduli. Consequently, at the same pre-unloading load level, they accumulate greater elastic strain energy. The release of this larger amount of stored energy to the coal component during unloading makes the coal more susceptible to brittle failure.

- (2)

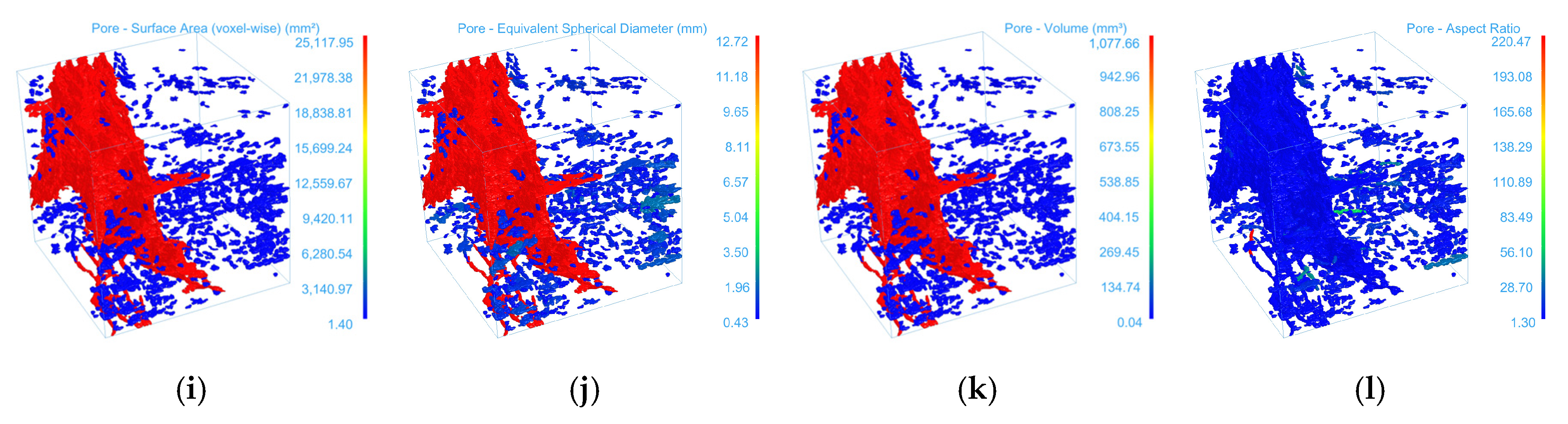

- The three-dimensional reconstruction results indicate that the mean volumes of fractures were 0.94 mm3, 0.70 mm3, and 1.56 mm3, with standard deviations reaching as high as 24.49, 13.83, and 38.10 mm3, respectively. The surface area could reach up to 25,117.95 mm2, and the maximum aspect ratio was 220.47. These findings demonstrate that the fracture system exhibits significant scale differentiation: a few dominant fractures control the overall flow and mechanical behavior, while a large number of micropores form a dispersed structural background. Fractures of different scales spatially assemble into a stratified, heterogeneous network, reflecting a pronounced parameter polarization phenomenon.

- (3)

- Analysis of two-dimensional slices indicates that the areal porosity, Euler number, and fractal dimension in the XY direction are all higher than those in the XZ and YZ directions. Taking specimen CM1 as an example, the fractal dimension in the XY direction remains stable between 1.83 and 1.86, while it is only 0.98–1.10 in the XZ direction and fluctuates between 0.40 and 1.40 in the YZ direction, demonstrating a strong directional dependence. For specimen CM3, the fractal dimension in the YZ direction gradually increases from 1.78 to 1.85, exhibiting a continuous evolutionary trend, indicating that fracture propagation and connectivity are highly anisotropic.

- (4)

- The fractal dimensions under different water content conditions exhibit pronounced stage-wise fluctuations: as the water content increases, the complexity of the fracture network significantly intensifies. The rising stages of fractal dimension correspond to periods of fracture connectivity and energy release, whereas the declining stages correspond to fracture closure and local reconstruction. The magnitude and frequency of fractal dimension variations can serve as quantitative indicators of the evolution and damage state of the internal fracture network within the coal matrix.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Yao, Q.; Xia, Z.; Xu, Q.; Yu, L.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Stability Evaluation of the Artificial Dam in Underground Reservoirs Under Storage and Drainage Cycles: A method based on concrete performance and case study. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 7725–7744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.B.; Li, Q.S.; Cao, Z.G.; Fang, J.; Wu, B.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, S.R.; Liu, X.Q.; Yang, Y.M. Evaluation of water resources carrying capacity in ecologically fragile mining areas under the influence of underground reservoirs in coal mines. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Kou, M.; Li, M. A review of stability of dam structures in coal mine underground reservoirs. Water 2024, 16, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez, J.; Loredo, J.; Galdo, M.; Fernández-Oro, J.M. Energy storage in underground coal mines in NW Spain: Assessment of an underground lower water reservoir and preliminary energy balance. Renew. Energy 2019, 134, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Zheng, C. Permeation-strain characteristics and damage constitutive model of coal specimens under the coupling effect of seepage and creep. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2024, 177, 105729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, C.Y.; Cao, S.G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, C.Z.; Du, S.Y.; Li, J.; Shan, C.H. Mechanical properties and damage evolution law of cemented-gangue-fly-ash backfill modified with different contents of recycled steel fibers. J. Cent. South Univ. 2025, 32, 2661–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, C.; Cao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Du, S.; Ma, R.; Wang, K.; Liu, Y. Flexural properties and damage evolution laws of scrap tire steel fiber-reinforced constructional backfill body. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 106, 112700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Luo, B.; Xu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Feng, L. Research on the capacity of underground reservoirs in coal mines to protect the groundwater resources: A case of Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine in Xuzhou, China. Water 2023, 15, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.S.; Yang, W.; Shan, R.L.; Wang, S.; Fang, J. Ultimate water level and deformation failures of the artificial dam in the coal mine underground reservoir. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 162, 108367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zeng, C.; Huang, J.; Pu, H.; Axel, P.; Zhang, B.; Habil, C.B.; Bai, H.; Meng, G.; et al. Discussion of the basic problems for the construction of underground pumped storage reservoir in abandoned coal mines. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 3308–3318. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Q.; Tang, C.; Xia, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Chong, Z.; Hui, X. Mechanisms of failure in coal specimens from underground water reservoir. Eng. Geol. 2020, 267, 105494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, Q.; Xue, G.; Li, R. Technology of underground reservoir construction and water resource utilization in Daliuta Coal Mine. Coal Sci. Technol. 2016, 44, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez, A.; Jardón, S.; Álvarez, R.; Andrés, C.; Pendás, F. Hydrogeological definition and applicability of abandoned coal mines as water reservoirs. J. Environ. Monit. 2012, 14, 2127–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Gao, J.; Jiang, B.; Han, J.; Chen, M. Experimental study on the mechanism of water-rock interaction in the coal mine underground reservoir. J. China Coal Soc. 2019, 12, 3760–3772. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Q.; Yu, L.; Chen, N.; Wang, W.; Xu, Q. Experimental Study on Damage and Failure of Coal--Pillar Dams in Coal Mine Underground Reservoir under Dynamic Load. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 5623650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ni, W.; Hao, X.; Li, H.; Shen, Y. A study on the development and evolution of fractures in the coal pillar dams of underground reservoirs in coal mines and their optimum size. Processes 2023, 11, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Song, H.; Xu, J.; Yang, L.; Li, Z. Storage coefficient calculation model of coal mine underground reservoir considering effect of effective stress. J. China Coal Soc. 2019, 44, 3750–3759. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, K.; Gao, J.; Yang, Y.; Bai, L.; Yan, J. Research on temporal patterns of water-rock interaction in the coal mine underground reservoir based on the dynamic simulation test. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 13819–13832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Bai, Q.; Han, P. A review of water rock interaction in underground coal mining: Problems and analysis. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Song, S.; Wu, B.; Li, X.; Yang, K. Study on deformation and fracture evolution of underground reservoir coal pillar dam under different mining conditions. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 2186698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, H.; Li, P.; Wu, M.; Hao, J.; Hu, Y. Water Quality Characteristics and Water-Rock Interaction Mechanisms of Coal Mine Underground Reservoirs. Acs Omega 2024, 9, 28726–28737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.F.; Xing, J.C.; Liang, B.; Zhang, J. Experimental study on deformation characteristics of rock and coal under stress-fluid interactions in coal mine underground water reservoir. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2024, 46, 7845–7860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, G.; Xing, Z.; Wang, L.; Zou, W. A Geological Site Selection Method of a Coal Mine Underground Reservoir and Its Application. Water 2023, 15, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, E.; Duan, H.; Chi, M.; Fan, J.; Hu, J.; Wu, B.; Yu, C.; Tong, J. Depth-dependent mechanical-seepage behavior and safety mining distance of the steeply inclined coal mine underground reservoir. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2025, 35, 1341–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Li, Y.; Dong, C.; Zhao, G.; Lu, X.; Qi, M.; Wang, X. Sandstone damage and acoustic emission characteristics under the cyclic loading and unloading of the intermediate principal stress of the true three-axis. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 862–872. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Wang, D.; Li, T.; Gao, S.; Chen, W.; Fan, R. Triaxial loading device for reliability tests of three-axis machine tools. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2018, 49, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, D.; Yu, B.; Li, S. Deformation and seepage characteristics of coal under true triaxial loading–unloading. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 2673–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Rong, C.; Shi, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R. Analysis of Mechanical Properties and Energy Evolution of Through-Double-Joint Sandy Slate Under Three-Axis Loading and Unloading Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Han, P.; Zhu, C.; He, M. Mechanical properties of coal and rock with different dip angles based on true triaxial unloading test. J. Min. Strat. Control Eng. 2024, 6, 023037. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, H.; Xiong, L.; Xu, Z. Conventional triaxial loading and unloading test and PFC numerical simulation of rock with single fracture. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2024, 70, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, D.; Yu, B.; Ren, K. Failure and deformation characteristics of shale subject to true triaxial stress loading and unloading under water retention and seepage. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 220530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, L.; Xie, J.; Zha, E. Mechanical and degradation properties of rock under triaxial loading-unloading stresses: Comparative insights into coal and sandstone. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2025, 190, 106102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Liu, D.Q.; He, M.C.; Yang, J.S. Excess energy characteristics of true triaxial multi-faceted rapid unloading rockburst. J. Cent. South Univ. 2024, 31, 1671–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, X.; Han, Z.; Ji, Y.; Qiao, Z. Reasonable size design and influencing factors analysis of the coal pillar dam of an underground reservoir in Daliuta mine. Processes 2023, 11, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Wu, B.; Cao, Z.; Li, P.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y. Research on instability mechanism and precursory information of coal pillar dam of underground reservoir in coal mine. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 51, 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Jia, S.; Huang, X.; Shi, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F. Accurate characterization method of pores and various minerals in coal based on CT scanning. Fuel 2024, 358, 130128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wei, J.; Yao, B.; Zhang, H.; Fu, J.; Zeng, F. Damage constitutive model of gas-bearing coal using industrial CT scanning technology. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 101, 104543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Wei, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, W.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X. Study on mechanical properties and crack propagation of raw coal with different bedding angles based on CT scanning. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 27185–27195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jia, S.; Ren, Z.; Bai, Q.; Wang, L.; Han, P. Strength evolution characteristics of coal with different pore structures and mineral inclusions based on CT scanning reconstruction. Nat. Resour. Res. 2024, 33, 2725–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.A. Complex interactions between coal maceral fractions, thermal maturity, reaction kinetics, fractal dimensions and pore-size distributions: Implications for gas storage. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2025, 305, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kong, X.; Nie, B.; Song, D.; He, X.; Wang, L. Pore fractal dimensions of bituminous coal reservoirs in north China and their impact on gas adsorption capacity. Nat. Resour. Res. 2021, 30, 4585–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Wang, P.; Lin, H.; Li, S.; Zhou, B.; Bai, Y.; Yan, D.; Ma, C. Quantitative characterization of the pore volume fractal dimensions for three kinds of liquid nitrogen frozen coal and its enlightenment to coalbed methane exploitation. Energy 2023, 263, 125741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Tian, S.; Jiao, A.; Cao, Z.; Song, K.; Zou, Y. Pore characteristics and fractal dimension analysis of tectonic coal and primary-structure coal: A case study of sanjia coal mine in Northern Guizhou. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 27300–27311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Xiao, X.; Cui, J.; Wu, D.; Pan, Y. Damage evolution, fractal dimension and a new crushing energy formula for coal with bursting liability. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 169, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen Type | Specimen ID | Confining Pressure Level/MPa | Water Content State (Rock–Coal) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ2 | σ3 | |||

| Sandstone–Coal Composite | CM1 | 15 | 10 | Dry-Natural |

| CM2 | 15 | 10 | Natural-Natural | |

| CM3 | 15 | 10 | Saturated-Natural | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Q.; Xia, Z.; Du, S.; Fan, Y.; Huang, G.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Fractal and CT Analysis of Water-Bearing Coal–Rock Composites Under True Triaxial Loading–Unloading. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120782

Xu Q, Xia Z, Du S, Fan Y, Huang G, Chen S, Zhang Z, Liu Y. Fractal and CT Analysis of Water-Bearing Coal–Rock Composites Under True Triaxial Loading–Unloading. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):782. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120782

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Qiang, Ze Xia, Shuyu Du, Yukuan Fan, Gang Huang, Shengyan Chen, Zhisen Zhang, and Yang Liu. 2025. "Fractal and CT Analysis of Water-Bearing Coal–Rock Composites Under True Triaxial Loading–Unloading" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120782

APA StyleXu, Q., Xia, Z., Du, S., Fan, Y., Huang, G., Chen, S., Zhang, Z., & Liu, Y. (2025). Fractal and CT Analysis of Water-Bearing Coal–Rock Composites Under True Triaxial Loading–Unloading. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120782