Total Pore–Throat Size Distribution Characteristics and Oiliness Differences Analysis of Different Oil-Bearing Tight Sandstone Reservoirs—A Case Study of Chang6 Reservoir in Xiasiwan Oilfield, Ordos Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

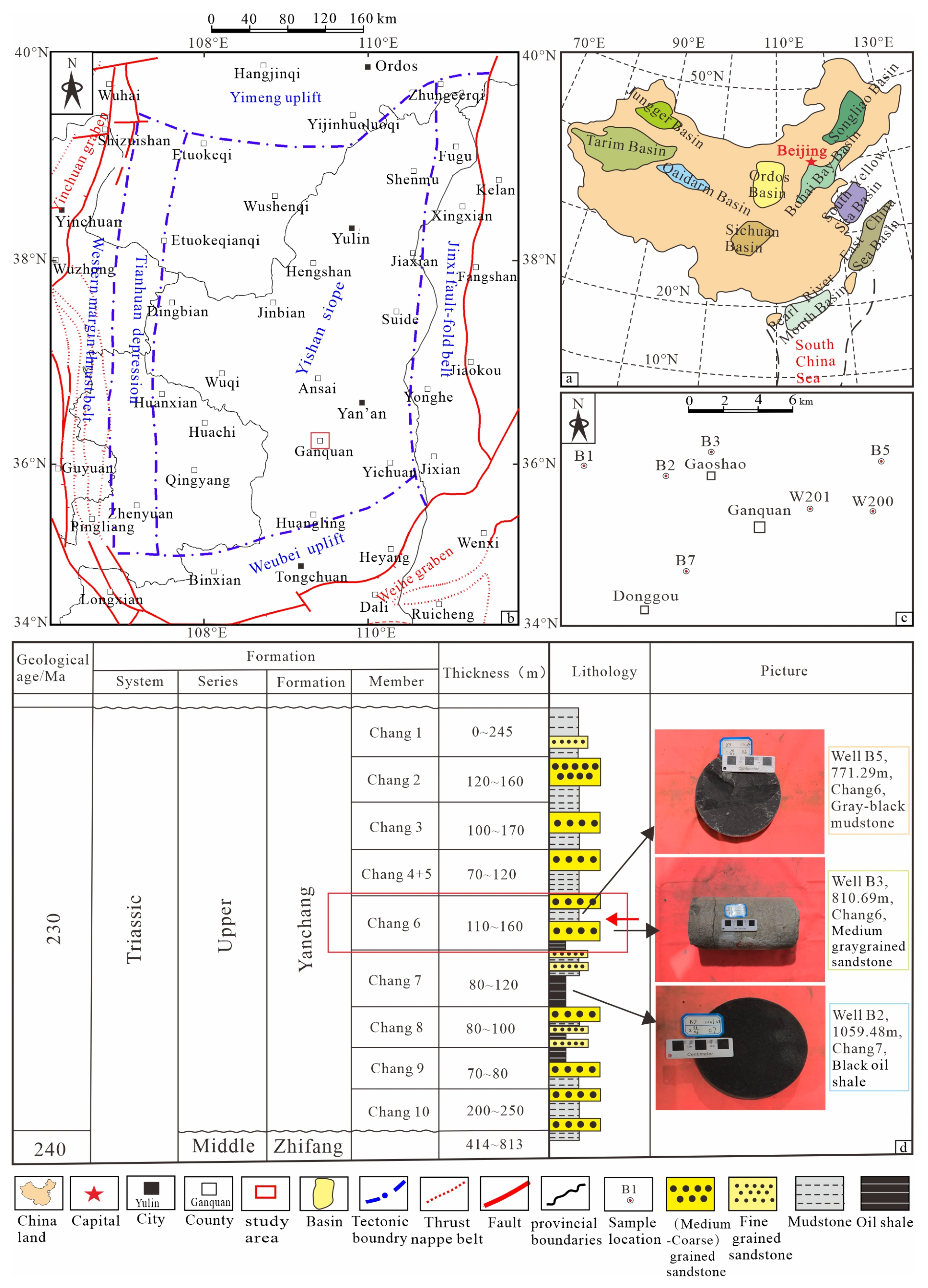

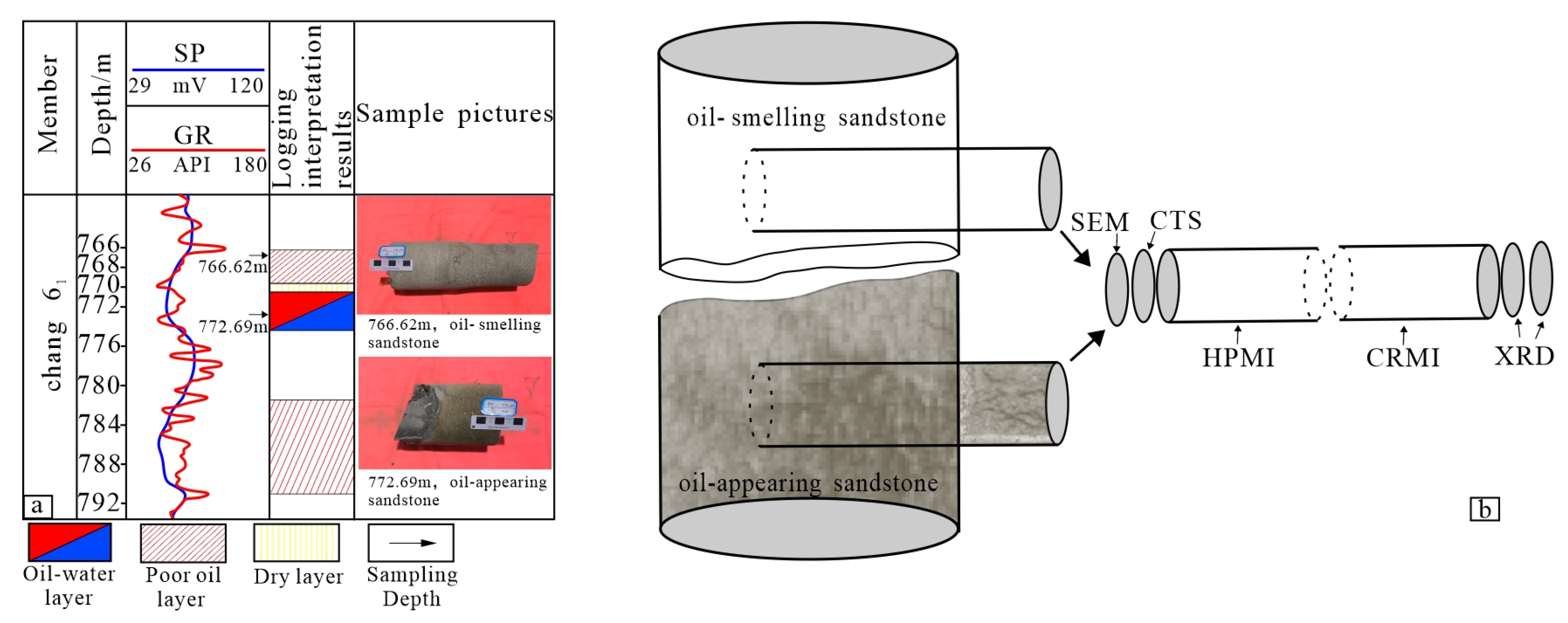

2. Geological Setting and Samples

3. Experimental Methods and Methodology

3.1. Experimental Methods

3.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction

3.1.2. High-Pressure Mercury Injection

3.1.3. Constant Rate Mercury Injection

3.2. Fractal Theory

4. Results

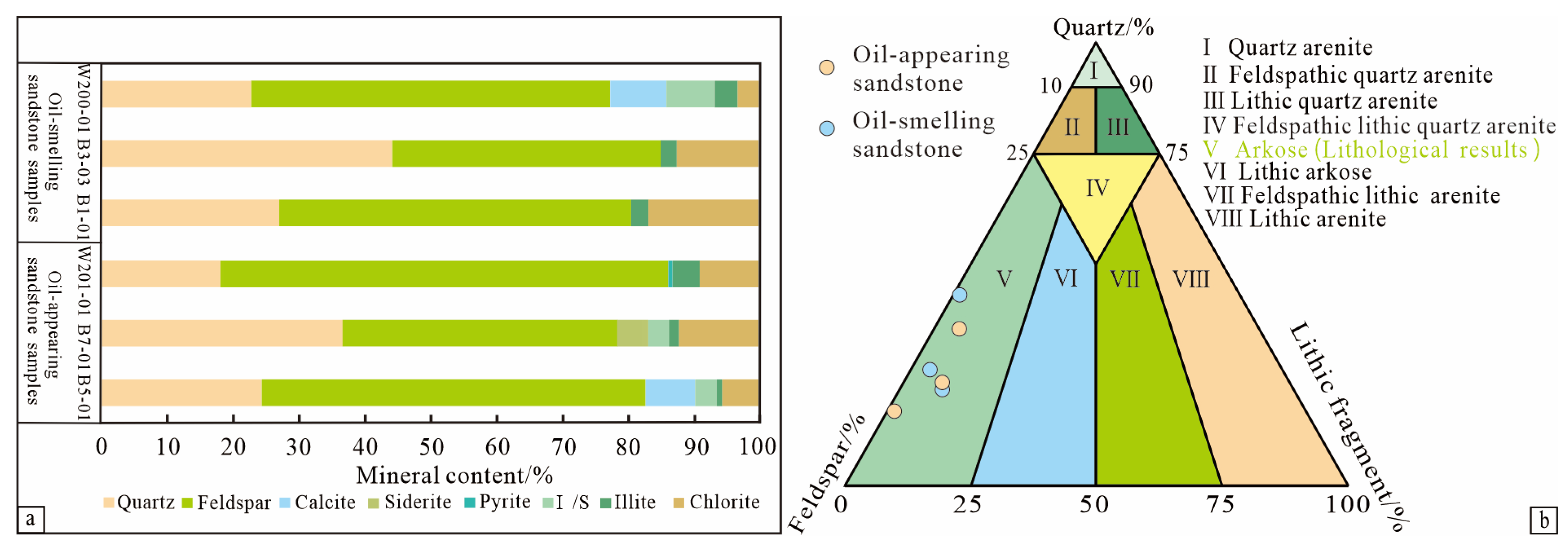

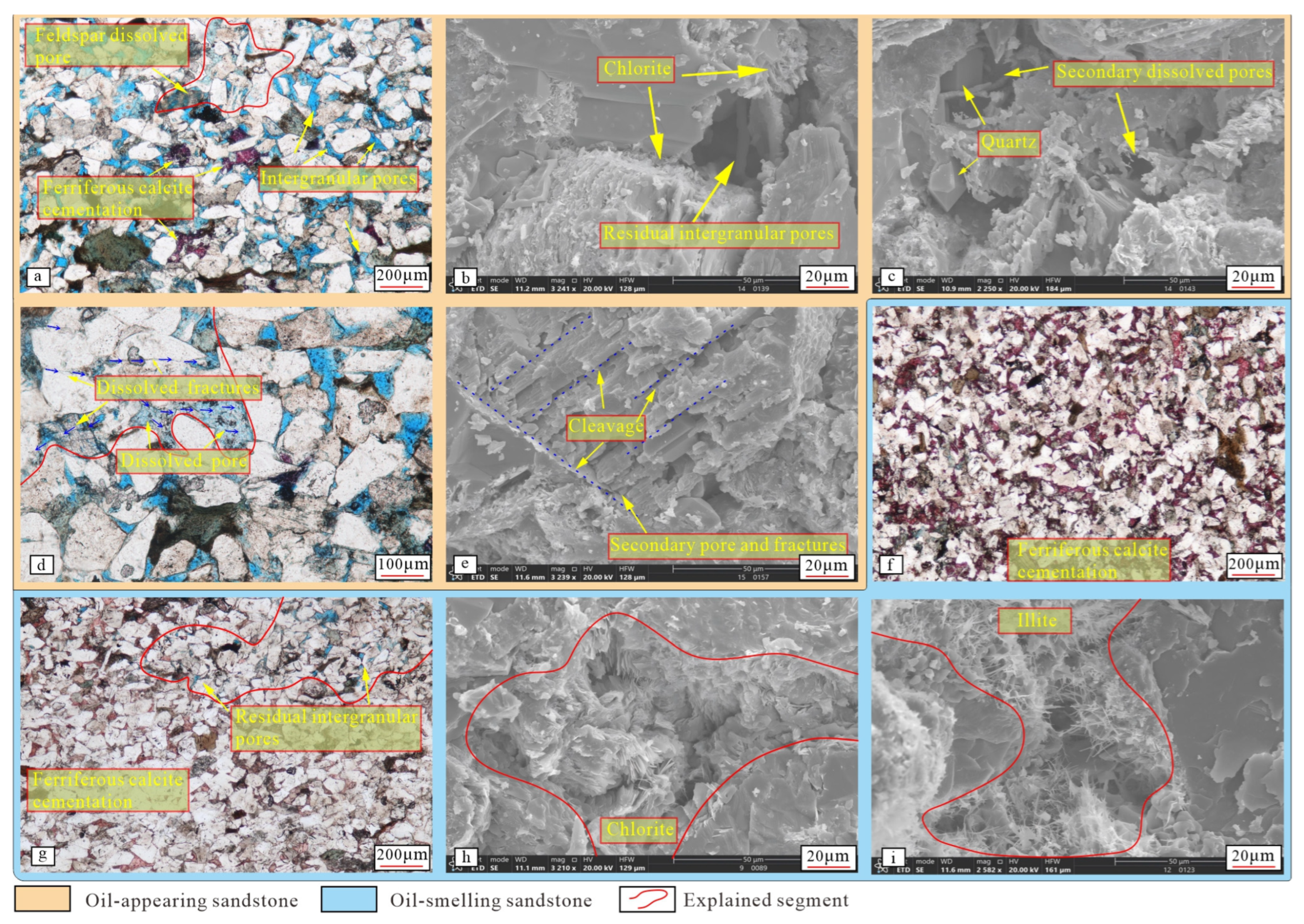

4.1. Petrological and Pore–Throat Characteristics

4.2. Characteristics of Pore–Throat Structure Determined by HPMI

4.3. Characteristics of Pore–Throat Structure Determined by CRMI

4.4. TPSD Characteristics

5. Discussion

5.1. Fractal Characteristics of TPSD

5.2. Relationship Between D and Mineral Composition

5.3. Relationship Between D and Pore–Throat Structure Parameters

5.4. Analysis of Causes of Oiliness Differences

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Although the two types of oil-bearing cores share a similar lithology (primarily composed of arkose), an obvious distinction lies in clay mineral composition. Compared with oil-appearing sandstone, the oil-smelling sandstone has poorer pore development along with a higher content of illite and chlorite, while exhibiting more pronounced impacts of destructive diagenetic processes on the pore–throat structure.

- (2)

- Concerning the results of the TPSD curves, the oil-appearing sandstone samples exhibit a symmetrical bimodal distribution and three-stage fractal characteristics. While the oil-smelling sandstone samples display a bimodal distribution characterized by a higher left peak and a lower right peak, they exhibit three-stage and four-stage fractal patterns. The pore space contribution further demonstrates that the oil-smelling sandstone samples have a greater reliance than the oil-appearing sandstone on small pores and throats below 0.12 μm. Under the influence of clastic mineral composition and content, clay mineral content, pore–throat size, and pore–throat sorting, the oil-smelling sandstone samples exhibit higher complexity compared with oil-appearing sandstone samples.

- (3)

- The oil-appearing sandstone is characterized by low clay mineral content, minimal destructive diagenesis, well-developed pores, and low pore–throat complexity, which is conducive to the hydrocarbon migration and accumulation within such reservoirs. These findings provide crucial guidance for reservoir evaluation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carvalho, A.; Ros, L. Diagenesis of Aptian sandstones and conglomerates of the Campos basin. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2015, 125, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Pang, X.; Song, Y. Whole petroleum system and ordered distribution pattern of conventional and unconventional oil and gas reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2015, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Sun, W.; Ji, W.; Chen, L.; Jiang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Tang, X.; Du, K.; Qu, Y.; Ouyang, S. Impact of laminae on gas storage capacity: A case study in Shanxi formation, Xiasiwan area, Ordos Basin, China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 60, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, R.; Tao, S.; Yuan, X.; Wang, X. Theory, technology and practice of unconventional petroleum geology. J. Earth Sci. 2023, 34, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, Y. Unconventional hydrocarbon resources in China and the prospect of exploration and development. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2012, 39, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yu, W. China’s unconventional oil and gas exploration and development: Progress and prospects. Resour. Sci. 2015, 37, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Zou, C.; Jia, A.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, R.; Wu, S.; Guo, Z. Development characteristics and orientation of tight oil and gas in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D. Situation of Chinas oil and gas exploration and development in recent years and relevant suggestions. Acta Pet. Sin. 2022, 43, 15–28+111. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Lu, S.; Hersi, O.S.; Wang, M.; Deng, S.; Lu, R. Reservoir spaces in tight sandstones: Classification, fractal characters, and heterogeneity. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 46, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Zeng, J.; Jiang, S.; Feng, S.; Feng, X.; Guo, Z.; Teng, J. Heterogeneity of reservoir quality and gas accumulation in tight sandstone reservoirs revealed by pore structure characterization and physical simulation. Fuel 2019, 253, 1300–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Xiao, W.L.; Zheng, L.L.; Lei, Q.H.; Qin, C.Z.; He, Y.A.; Chen, M. Pore throat structure heterogeneity and its effect on gas-phase seepage capacity in tight sandstone reservoirs: A case study from the Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 2892–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, R.; Yin, S. Comprehensive Study on Microscopic Pore Structure and Displacement Mechanism of Tight Sandstone Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Chang3 Member in the Weibei Oilfield, Ordos Basin, China. Energies 2024, 17, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, T.; Wang, X.; Gao, H.; Ni, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C. Distribution characteristics and its influence factors of movable fluid in tight sandstone reservoir: A case study from Chang8 oil layer of Yanchang Formation in Jiyuan oilfield, Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2019, 40, 557. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, X.; Zhu, Y.; Jiao, T.; Qi, Z.; Luo, J.; Xie, Y.; Liu, L. Microscopic pore throat structures and water flooding in heterogeneous low-permeability sandstone reservoirs: A case study of the Jurassic Yan’an Formation in the Huanjiang area, Ordos Basin, Northern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2021, 219, 104903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Tong, Q.; Cao, C.; Zhang, Y. Effect of pore-throat structure on movable fluid and gas–water seepage in tight sandstone from the southeastern Ordos Basin, China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Jia, C.; Jin, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, M.; Huang, Z. The characteristics of movable fluid in the Triassic lacustrine tight oil reservoir: A case study of the Chang7 member of Xin’anbian Block, Ordos Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 102, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, A.; Fu, S.; Tian, W. Influence of micro-pore structure in tight sandstone reservoir on the seepage and water-drive producing mechanism—A case study from Chang6 reservoir in Huaqing area of Ordos basin. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jiao, T.; Huang, H.; Qi, Z.; Jiang, T.; Chen, G.; Jia, N. Pore structure and fractal characteristics of ultralow-permeability sandstone reservoirs in the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin. Interpretation 2021, 9, T747–T765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, Z.; Li, P.; Liu, J. Microscopic pore-throat structure variability in low-permeability sandstone reservoirs and its impact on water-flooding efficacy: Insights from the Chang 8 reservoir in the Maling Oilfield, Ordos Basin, China. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2024, 42, 1554–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wei, W.; Wei, X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, X. Microstructural characterization and development trend of tight sandstone reservoirs. J. Oil Gas Technol. 2013, 35, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Li, J.; Xiao, D.; Xue, H.; Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Li, Z. Research progress of microscopic pore–throat classification and grading evaluation of shale reservoirs: A minireview. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 4677–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, J.; Gooddy, D.; Bright, M.; Williams, P. Pore-throat size distributions in Permo-Triassic sandstones from the United Kingdom and some implications for contaminant hydrogeology. Hydrogeol. J. 2001, 9, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shen, P.; Song, Z.; Yang, H. Characteristics of micro-pore throat in ultra-low permeability sandstone reservoir. Acta Pet. Sin. 2009, 30, 560. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Q.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X. Characteristics of pore-throat structure and mass transport in ultra-low permeability reservoir. Key Eng. Mater. 2013, 562, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, N.; Zhou, C.; Dang, Y.; Shao, F.; Li, M. Combined technology of PCP and nano-CT quantitative characterization of dense oil reservoir pore throat characteristics. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Ge, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, D. Effect of pore-throat structure on air-foam flooding performance in a low-permeability reservoir. Fuel 2023, 349, 128620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Ning, Z.; Sun, Y.; Ding, G.; Du, H. Pore structure characterization of tight oil reservoirs by a combined mercury method. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2017, 39, 700–705. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, C.R.; Solano, N.; Bustin, R.M.; Bustin, A.M.M.; Chalmers, G.R.L.; He, L.; Melnichenko, Y.B.; Radli’nski, A.P.; Blach, T.P. Pore structure characterization of North American shale gas reservoirs using USANS/SANS, gas adsorption, and mercury intrusion. Fuel 2013, 103, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Jiang, S.; Thul, D.; Lu, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, B. Impacts of clay on pore structure, storage and percolation of tight sandstones from the Songliao Basin, China: Implications for genetic classification of tight sandstone reservoirs. Fuel 2018, 211, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Hu, Q.; Yang, S.; Zhang, T.; Qiao, H.; Meng, M.; Zhu, X.; Sun, X. Pore structure typing and fractal characteristics of lacustrine shale from Kongdian Formation in East China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 85, 103709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Zheng, M.Y.; Lv, W.; Xiao, Q.; Xiang, Q.; Yao, L.; Feng, C. Experimental study on microscopic production characteristics and influencing factors during dynamic imbibition of shale reservoir with online NMR and fractal theory. Energy 2024, 310, 133244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Lu, M.; Zhou, C.; Xu, J.; Hu, K.; Zhu, Y. Study of the full pore size distribution and fractal characteristics of ultralow permeability reservoir. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2020, 49, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, D.; Lu, S.; Lu, Z.; Huang, W.; Gu, M. Combining nuclear magnetic resonance and rate-controlled porosimetry to probe the pore-throat structure of tight sandstones. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2016, 43, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Sun, W.; Tao, R.; Luo, B.; Chen, L.; Ren, D. Pore–throat structure and fractal characteristics of tight sandstones in Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 120, 104573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Study on Microscopic Pore Throat Structure and Grading Evaluation of Chang7 Tight Sandstone Reservoirs in Jiyuan Area, Ordos Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwest University, Xi’an, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, H.; Shang, Y.; Cui, G. Fractal characterization of the pore-throat structure in tight sandstone based on low-temperature nitrogen gas adsorption and high-pressure mercury injection. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peta, K.; Stemp, W.J.; Stocking, T.; Chen, R.; Love, G.; Gleason, M.A.; Houk, B.A.; Brown, C.A. Multiscale Geometric Characterization and Discrimination of Dermatoglyphs (Fingerprints) on Hardened Clay—A Novel Archaeological Application of the GelSight Max. Materials 2025, 18, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Liao, C.; Luo, Y.; Ji, K. Fractal theory-based permeability model of fracture networks in coals. Coal Geol. Explor. 2023, 51, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; LI, X.; X, H. Study on Fracture Development Law of Overlying Coal Rock Based on Fractal Theory. Min. R D 2023, 43, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.; Xie, Q.; Qu, X.; Chu, M.; Li, S.; Ma, D.; Ma, X. Fractal characteristics of pore-throat structure and permeability estimation of tight sandstone reservoirs: A case study of Chang 7 of the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation in Longdong area, Ordos Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 184, 106555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, L.; Wu, Z.; Ma, J. Pore-throat structure, fractal characteristics and permeability prediction of tight sandstone: The Yanchang Formation, Southeast Ordos Basin. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shi, Y.; Xu, S.; Wei, R.; Liu, Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, X. Evaluation method of rock mechanical parameters and brittleness characteristics based on rock cuttings fractal theory. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 254, 214031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F.; Chen, H. Attributes of the Mesozoic structure on the west margin of the Ordos Basin. Acta Geol. Sin. 2005, 79, 737–747. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D. Transverse structure in the middle of west margin of Ordos Basin. J. Northwest Univ. 2009, 39, 490–496. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X. Provenance and sediment dispersal of the Triassic Yanchang Formation, southwest Ordos Basin, China, and its implications. Sediment. Geol. 2016, 335, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Yang, X.; Su, C. Relationship between Helanshan basin and Ordos basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2006, 27, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, T. Structural features of the middle section and its petroleum exploration prospects in the west margin of Ordos Basin. Geoscience 2016, 30, 274–285. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, Y.; Song, H.; Li, D. Geological characteristics and main controlling factors of hydrocarbon accumulation in Chang 7 tight oil of Yanchang Formation of Xiasiwan area, Ordos Basin. J. Cent. South Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2014, 45, 4267–4276. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, K.; Cao, Y.; Liu, K.; Wu, S.; Yuan, G.; Zhu, R.; Kashif, M.; Zhao, Y. Diagenesis of tight sandstone reservoirs in the upper triassic Yanchang Formation, southwestern Ordos Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 99, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Chen, Y.; Pu, R. Analysis of the factors influencing movable fluid in shale oil reservoirs: A case study of Chang 7 in the Ordos Basin, China. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2024, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, C.; Wei, D.; Wang, C.; He, Y.; Ge, Y.; Wei, W. Formation, distribution, and exploration strategies of tight oil in the Member 6 of Triassic Yanchang Formation in southeastern Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2025, 46, 335. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, A.; Cheng, G.; Li, D.; Ding, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, G.; Yang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, L. Micropore structure and micro residual oil distribution of ultra-low permeable reservoir: A case study of chang4+5 of Baibao area, Wuqi Oilfield. J. Jilin Univ. 2023, 53, 1338–1351. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 29171-2023; Rock Capillary Pressure Measurement. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Washburn, E.W. The Dynamics of capillary flow. Phys. Rev. 1921, 17, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. On the geometry of homogeneous turbulence with stress on the fractal dimension of the iso-surfaces of scalars. J. Fluid Mech. 1975, 72, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Passoja, D.E.; Paullay, A.J. Fractal character of fracture surfaces of metals. Nature 1984, 308, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Sun, W.; Liu, Y.; Luo, B.; Zhao, M. Effect of pore networks on the properties of movable fluids in tight sandstones from the perspective of multi-techniques. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2021, 201, 108449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Guan, P.; Zhang, J.; Liang, X.; Ding, X.; You, Y. A review of the progress on fractal theory to characterize the pore structure of unconventional oil and gas reservoirs. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2023, 59, 897–908. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Ruan, J.; Yan, N.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y. Effects of pore-throat structures on the fluid mobility in Chang 7 tight sandstone reservoirs of longdong area, Ordos Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 135, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.H.; Corey, A.T. Hydraulic Properties of Porous Media; Hydro Paper No. 5; Colorado State University: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Garzanti, E. Petrographic classification of sand and sandstone. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 192, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Ouyang, S.; Luo, B.; Zhao, D.; Sun, W.; Zang, Q. Investigation of pore-throat structure and fractal characteristics of tight sandstones using HPMI, CRMI, and NMR methods: A case study of the lower Shihezi Formation in the Sulige area, Ordos Basin. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 210, 110053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Sun, W.; Wu, H.; Huang, S.; Li, T.; Ren, D.; Chen, B. Impacts of pore-throat spaces on movable fluid: Implications for understanding the tight oil exploitation process. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 137, 105509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zheng, M.; Bi, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, X. Pore throat structure and fractal characteristics of tight oil sandstone: A case study in the Ordos Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 149, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, G.; Yang, C.; Deng, H.; Zhu, X.; Li, M. Pore-throat structure characteristics and fluid mobility analysis of tight sandstone reservoirs in Shaximiao Formation, Central Sichuan. Geol. J. 2023, 58, 4243–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Difference of Microscopic Characteristics of Tight Sandstone Reservoirs and Its Influence on Movable Fluid in Longdong Area, Ordos Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwest University, Xi’an, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Shi, Z.; Tian, Y.; Xie, D.; Li, W. The combination of high-pressure mercury injection and rate-controlled mercury injection to characterize the pore-throat structure in tight sandstone reservoirs. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2021, 28, 14–20+32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Shen, B.J.; Liu, Y.L.; Bi, H.; Liu, Z.B.; Bian, R.K.; Wang, P.; Li, P. The fractal characteristics of the pore throat structure of tight sandstone and its influence on oil content: A case study of the Chang 7 Member of the Ordos Basin, China. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 2262–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Ren, J.; Tan, M.; Song, J. Fractal evolution of sandstone material under combined thermal and mechanical action: Microscopic pore structure and macroscopic fracture characteristics. Mater. Lett. 2025, 389, 138388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Chen, D.; Zhang, W.; Yang, H.; Wu, H.; Cheng, X.; Qu, Y.; He, M. Movable fluid distribution characteristics and microscopic mechanism of tight reservoir in Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 840875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Lu, S.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Li, J. Evolution mechanism of micro/nano-scale pores in volcanic weathering crust reservoir in the Kalagang Formation in Santanghu Basin and their relationship with oil-bearing property. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 40, 1281–1294+1307. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, W.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, R.; Jin, Z.; Chen, Y. Control factors of reservoir oil-bearing difference of Cretaceous Mishrif Formation in the H oilfield, Iraq. Oil Gas Geol. 2019, 46, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tang, X.; Zan, L.; Hua, C.; Feng, H.; Chen, X.; Zheng, F.; Chen, Z. Shale lithofacies combinations and their influence on oil bearing property in the2nd Member of Funing Formation, Qintong sag. China Offshore Oil Gas 2024, 36, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.; Wang, G.; Wu, J.; Cai, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, M. Influence of differential diagenesis of Chang 8 tight sandstone reservoirs in Qingcheng area on oil bearing properties. Pet. Geol. Recovery Eff. 2025, 32, 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Chen, K.; Liu, Q.; Nian, T.; Guo, R. Mechanism Analysis of Oil-bearing Differences of Tight Sandstones in Ordos Basin A Case Study of Chang 812 Reservoir in Maling Area. J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ. 2025, 40, 11–20+32. [Google Scholar]

| HPMI | CRMI | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Types | Sample ID | Well | Depth/m | K (10−3 μm2) | Φ (%) | Pcd (MPa) | Rmax (μm) | Ra (μm) | R50 (μm) | Sp | Smax (%) | We (%) | Pcd (MPa) | Rt (μm) | Rp (μm) | Smax (%) |

| Oil-appearing sandstone | W201-01 | W201 | 891.12 | 1.154 | 13.978 | 0.138 | 5.331 | 0.974 | 0.636 | 2.841 | 98.561 | 38.599 | 0.232 | 2.128 | 138.07 | 75.39 |

| B7-01 | B7 | 824.3 | 0.023 | 8.556 | 0.674 | 1.091 | 0.244 | 0.151 | 2.383 | 96.164 | 37.008 | 0.219 | 2.149 | 146.85 | 71.97 | |

| B5-01 | B5 | 766.32 | 0.652 | 7.904 | 1.367 | 0.538 | 0.129 | 0.099 | 1.813 | 95.296 | 22.123 | 0.372 | 1.206 | 125.19 | 51.93 | |

| Average | 0.610 | 10.146 | 0.726 | 2.320 | 0.449 | 0.295 | 2.346 | 96.674 | 32.577 | 0.274 | 1.828 | 136.70 | 66.43 | |||

| Oil-smelling sandstone | B1-01 | B1 | 774.86 | 0.008 | 6.338 | 5.498 | 0.134 | 0.033 | 0.025 | 1.544 | 93.223 | 31.087 | 3.684 | 7.5 | 205 | 15.68 |

| B3-03 | B3 | 768.35 | 0.097 | 8.314 | 4.129 | 0.178 | 0.047 | 0.038 | 1.479 | 95.746 | 26.095 | 3.613 | 9.412 | 157.65 | 20.38 | |

| W200-01 | W200 | 959.09 | 0.003 | 6.650 | 2.052 | 0.358 | 0.078 | 0.018 | 2.234 | 89.321 | 19.558 | 2.963 | 0.184 | 115.03 | 25.25 | |

| Average | 0.036 | 6.101 | 3.893 | 0.223 | 0.053 | 0.027 | 1.752 | 92.763 | 25.580 | 3.420 | 5.699 | 159.23 | 20.44 | |||

| Lithofacies | Samples ID | D1 | R2 | S1 | D2 | R2 | S2 | D3 | R2 | S3 | D4 | R2 | S4 | DT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil-appearing sandstone samples | W201-1 | 2.130 | 0.982 | 7.678 | 2.510 | 0.998 | 82.985 | 2.960 | 0.913 | 9.336 | - | - | - | 2.523 |

| B5-01 | 2.395 | 0.993 | 14.891 | 2.521 | 0.984 | 75.456 | 2.957 | 0.828 | 9.653 | - | - | - | 2.544 | |

| B7-01 | 2.099 | 0.989 | 13.621 | 2.617 | 0.998 | 77.284 | 2.953 | 0.948 | 9.095 | - | - | - | 2.577 | |

| Average | 2.208 | 0.988 | 12.064 | 2.549 | 0.994 | 78.575 | 2.957 | 0.896 | 9.361 | - | - | - | 2.548 | |

| Oil-smelling sandstone samples | W200-01 | 2.239 | 0.942 | 41.246 | 2.806 | 0.995 | 30.218 | 2.661 | 0.930 | 25.983 | 2.989 | 0.930 | 2.553 | 2.539 |

| W200-01 (weighted mean) | 2.479 | - | - | 2.690 | - | - | 2.989 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B1-01 | 2.350 | 0.969 | 79.112 | 2.983 | 0.925 | 9.936 | 2.932 | 0.936 | 10.952 | - | - | - | 2.477 | |

| B3-03 | 2.304 | 0.983 | 79.872 | 2.978 | 0.898 | 8.234 | 2.919 | 0.981 | 11.894 | - | - | - | 2.433 | |

| Average | 2.378 | 0.964 | 66.743 | 2.884 | 0.939 | 16.129 | 2.946 | 0.947 | 16.277 | - | - | - | 2.483 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiong, A.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, Z.; Fan, P.; Liu, X.; Chai, R.; Xu, L.; Zhao, H.; Liu, D.; Chen, Z.; et al. Total Pore–Throat Size Distribution Characteristics and Oiliness Differences Analysis of Different Oil-Bearing Tight Sandstone Reservoirs—A Case Study of Chang6 Reservoir in Xiasiwan Oilfield, Ordos Basin. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 729. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110729

Xiong A, Zhou Y, Shen Z, Fan P, Liu X, Chai R, Xu L, Zhao H, Liu D, Chen Z, et al. Total Pore–Throat Size Distribution Characteristics and Oiliness Differences Analysis of Different Oil-Bearing Tight Sandstone Reservoirs—A Case Study of Chang6 Reservoir in Xiasiwan Oilfield, Ordos Basin. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(11):729. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110729

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiong, Anliang, Yanan Zhou, Zhenzhen Shen, Pingtian Fan, Xuefeng Liu, Ruiyang Chai, Longlong Xu, Hao Zhao, Dongwei Liu, Zhenwei Chen, and et al. 2025. "Total Pore–Throat Size Distribution Characteristics and Oiliness Differences Analysis of Different Oil-Bearing Tight Sandstone Reservoirs—A Case Study of Chang6 Reservoir in Xiasiwan Oilfield, Ordos Basin" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 11: 729. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110729

APA StyleXiong, A., Zhou, Y., Shen, Z., Fan, P., Liu, X., Chai, R., Xu, L., Zhao, H., Liu, D., Chen, Z., & Zhang, J. (2025). Total Pore–Throat Size Distribution Characteristics and Oiliness Differences Analysis of Different Oil-Bearing Tight Sandstone Reservoirs—A Case Study of Chang6 Reservoir in Xiasiwan Oilfield, Ordos Basin. Fractal and Fractional, 9(11), 729. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110729