Nonlinear Stochastic Wave Behavior: Soliton Solutions and Energy Analysis of Kairat-II and Kairat-X Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Analysis

- (i)

- *

- , since it starts at zero.

- *

- There is no statistical relationship between the increments.

Foris a continuous function.- *

- The distribution of increments is characterized by a Gaussian distribution with a mean of 0 and a variance of

- (ii)

- In mathematics, white noise, which is the time derivative of the Wiener process, is used to represent events with pronounced and obvious oscillations in an abstract manner.

3. EDAT

NPREA

4. Application of EDAT

- Simplifies the system of equations by eliminating unbalanced polynomial terms;

- Ensures the realness and boundedness of the resulting solutions;

- Selects the type of nonlinear wave to be obtained (e.g., bright, dark, kink, or bell-type).

5. Application of NPREA

6. EBA for Stochastic Soliton Dynamics

7. Result and Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garabedian, P.R. Partial Differential Equations; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2023; Volume 325. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, J. Partial Differential Equations; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, S.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, S.; Osman, M.S. New Exact Solutions of (3 + 1)-Dimensional Modified KdV-Zakharov-Kunznetsov Equation by Sardar-Subequation Method. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, A.H.; AlBaidani, M.M.; Wazwaz, A.M.; Ma, W.X.; Shamima, U.; Ullah, M.S. Soliton Dynamics and Chaotic Analysis of the Biswas-Arshed Model. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.S.; Ali, M.Z.; Roshid, H.O. Bifurcation, Chaos, and Stability Analysis to the Second Fractional WBBM Model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, M.I.; Ullah, M.S.; Rahman, Z.; Akter, R. Novel Dynamics of the Fokas-Lenells Model in Birefringent Fibers Applying Different Integration Algorithms. Int. J. Math. Comput. Eng. 2025, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazwaz, A.M. Extended (3 + 1)-Dimensional Kairat-II and Kairat-X Equation: Painlevé Integrability, Multiple Soliton Solutions, Lump Solution, and Breather Wave Solution. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2024, 34, 2177–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, M.S.; Wazwaz, A.M. Tri-Analytical Approach to Kairat-II and Kairat-X Equations. Rom. Rep. Phys. 2024, 77, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateen, A.; Tipu, G.H.; Ciurdariu, L.; Yao, F. Analytical Soliton Solutions of the Kairat-II Equation Using the Kumar-Malik and Extended Hyperbolic Function Methods. AIMS Math. 2025, 10, 8721–8752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhakim, L.; Gasmi, B.; Moussa, A.; Mati, Y. Bifurcation, Chaotic Behaviour and Soliton Solutions of the Kairat-II Equation via Two Analytical Methods. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 2025, 13, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, Y.; Jan, M.; Naila, N.; Aziz, K.; Thabet, A. On the Comparative Analysis for the Fractional Solitary Wave Profiles to the Recently Developed Nonlinear System. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadalla, M.; Zafar, A.; Taishiyeva, A.; Raheel, M.; Myrzakulov, R.; Bekir, A. Analytical Solutions to the M-Fractional Kairat-II and Kairat-X Equations. Front. Phys. 2023, 11, 1335423. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, W.W.; Cesarano, C.; Al-Askar, F.M.; El-Morshedy, M. Solitary Wave Solutions for the Stochastic Fractional-Space KdV in the Sense of the M-Truncated Derivative. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Askar, F.M.; Cesarano, C.; Mohammed, W.W. Analytical Solutions of Stochastic–Fractional Drinfel’d-Sokolov-Wilson Equations via (G’/G)-Expansion Method. Symmetry 2022, 14, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javad, V.; Ali, Z.; Hadi, R.; Reza, A. New Extended Direct Algebraic Method for the Resonant Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation with Kerr Law Nonlinearity. Optik 2021, 227, 165936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.J.; Liu, J.H. On Abundant Wave Structures of the Unsteady Korteweg-de Vries Equation Arising in Shallow Water. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2023, 8, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Model | Techniques Used | Key Outcomes/Visualizations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | Kairat-II | Extended hyperbolic; Kumar–Malik | Bright, dark, Jacobi elliptic solutions; graphs of multiple wave types. |

| [10] | Kairat-II | Bifurcation theory; phase portraits | Chaotic dynamics identification; critical transition analysis via soliton theory. |

| [11] | Fractional Kairat-II | M-truncated/ -fractional derivatives | Accurate solitary wave behavior; 2D/3D graphs under fractional effects. |

| [12] | Kairat-X and fractional Kairat-II | Exact analytical construction | Contour, 2D, and 3D visualizations relevant to optical and ferromagnetic media. |

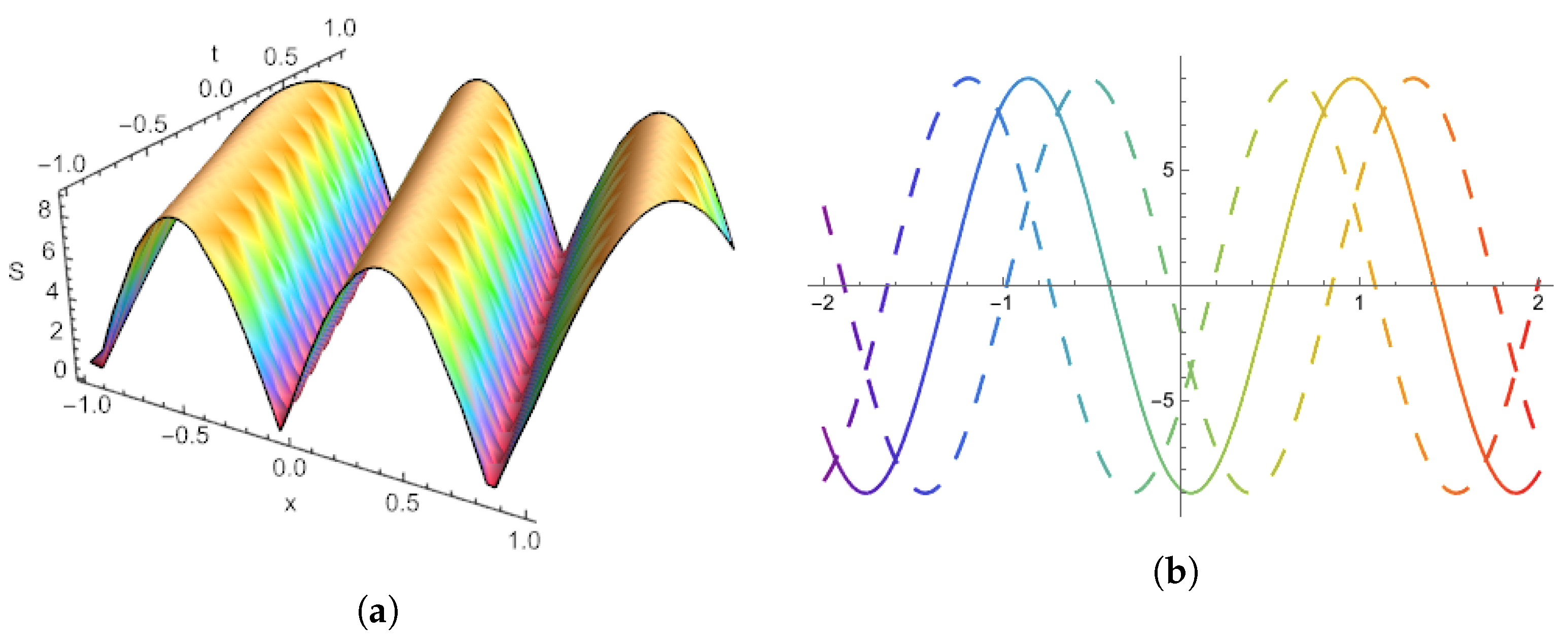

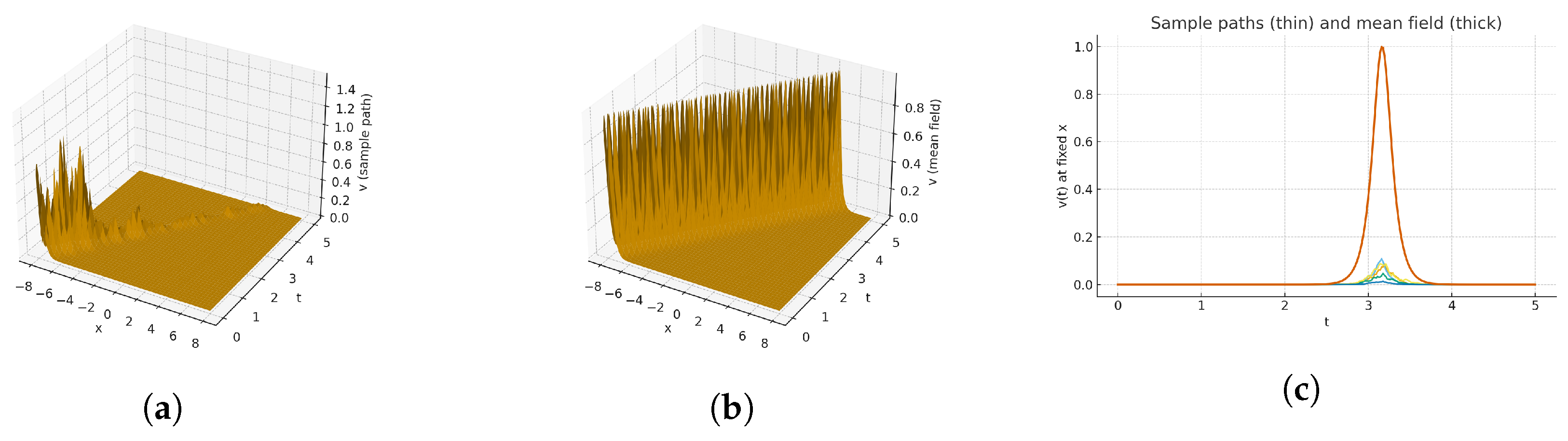

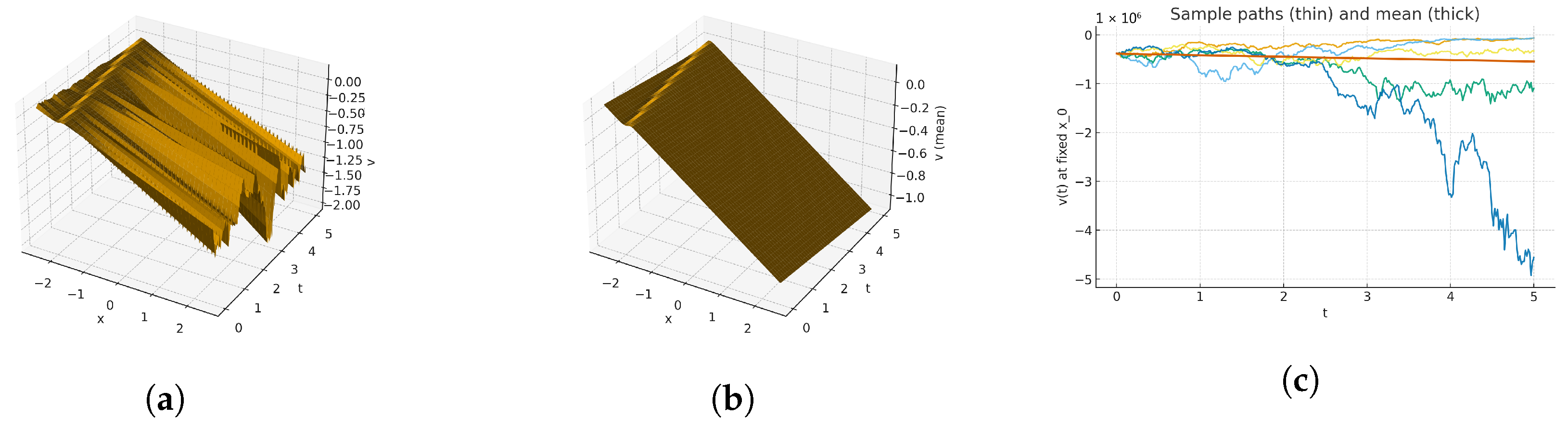

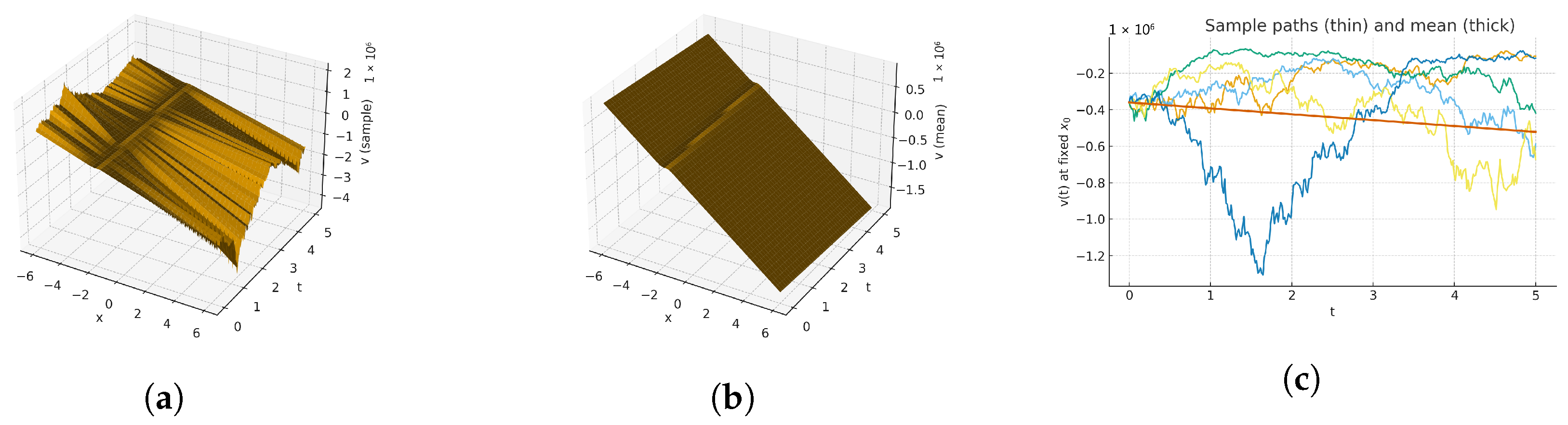

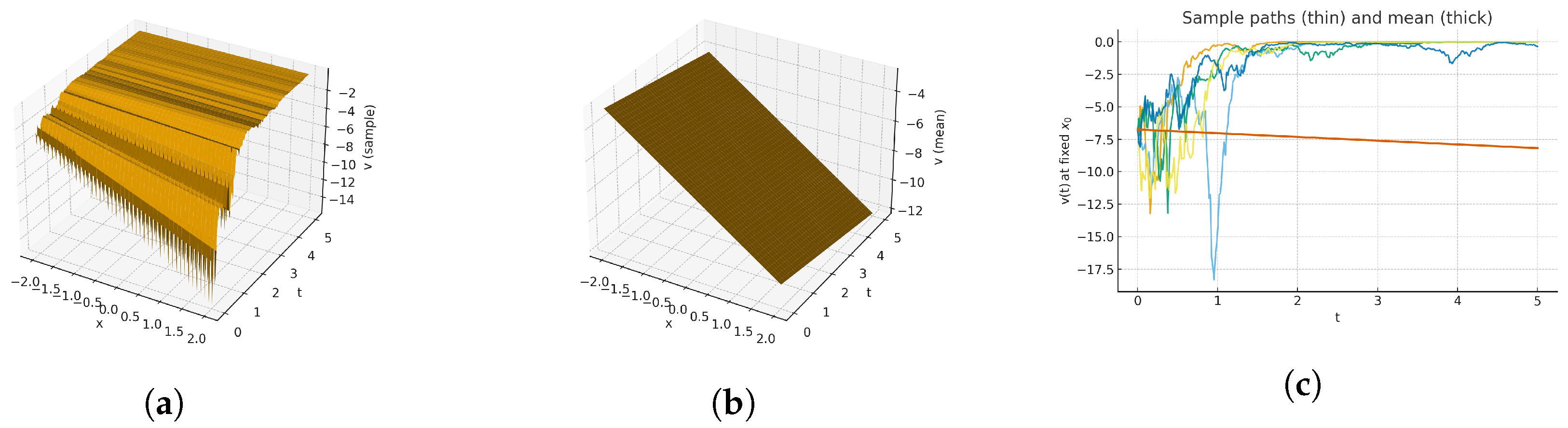

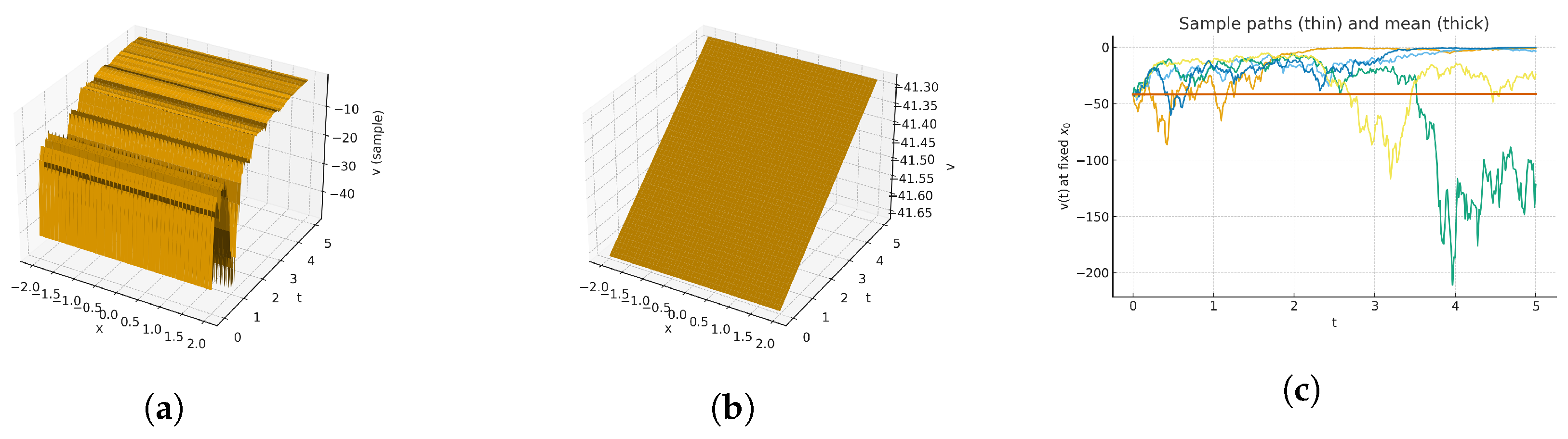

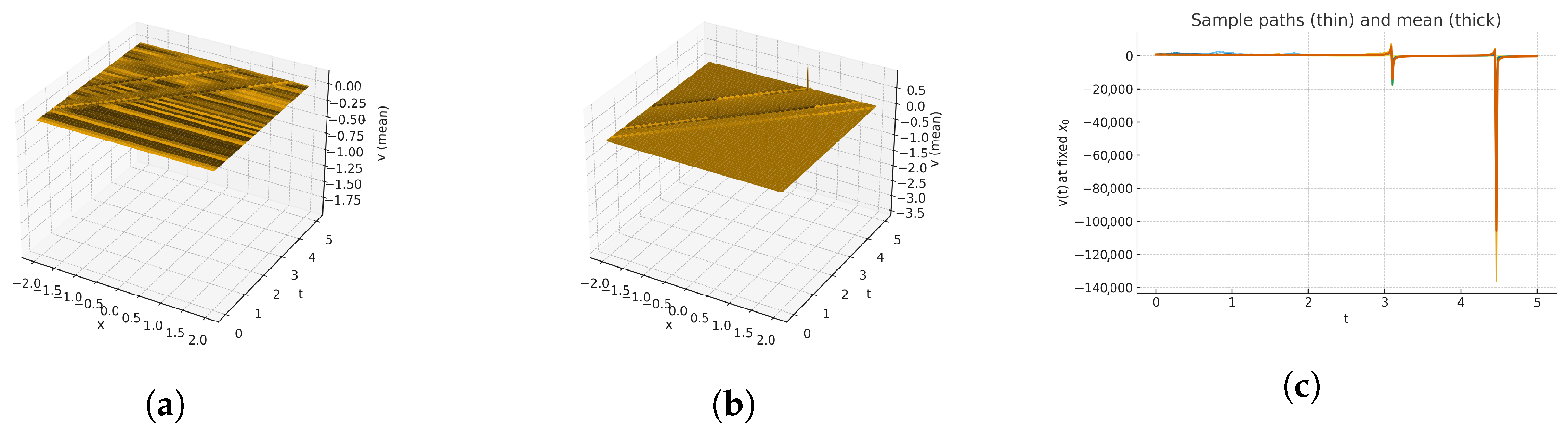

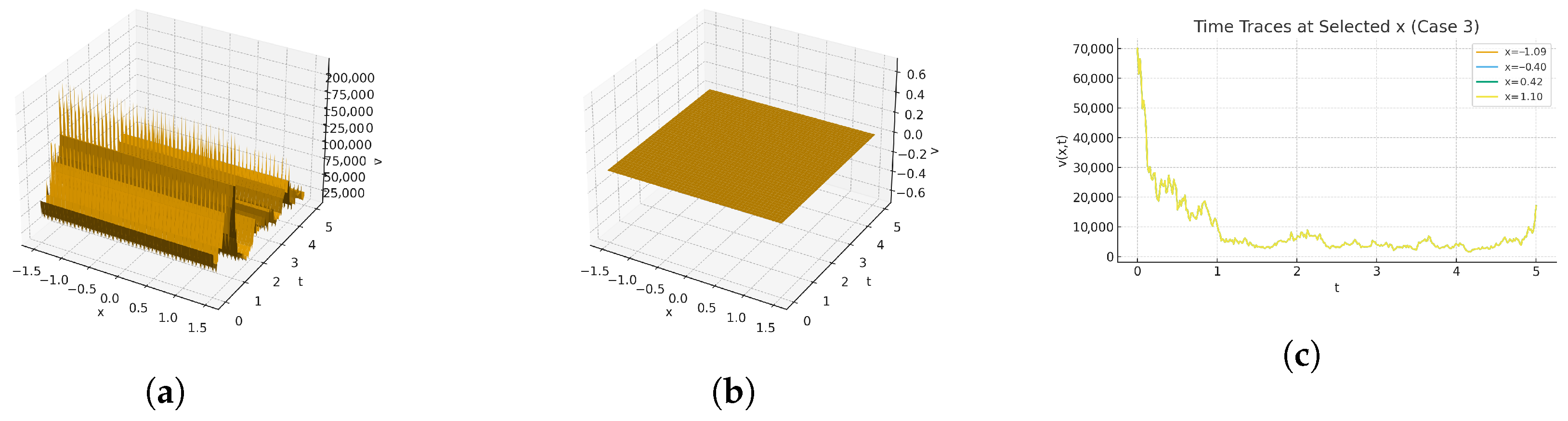

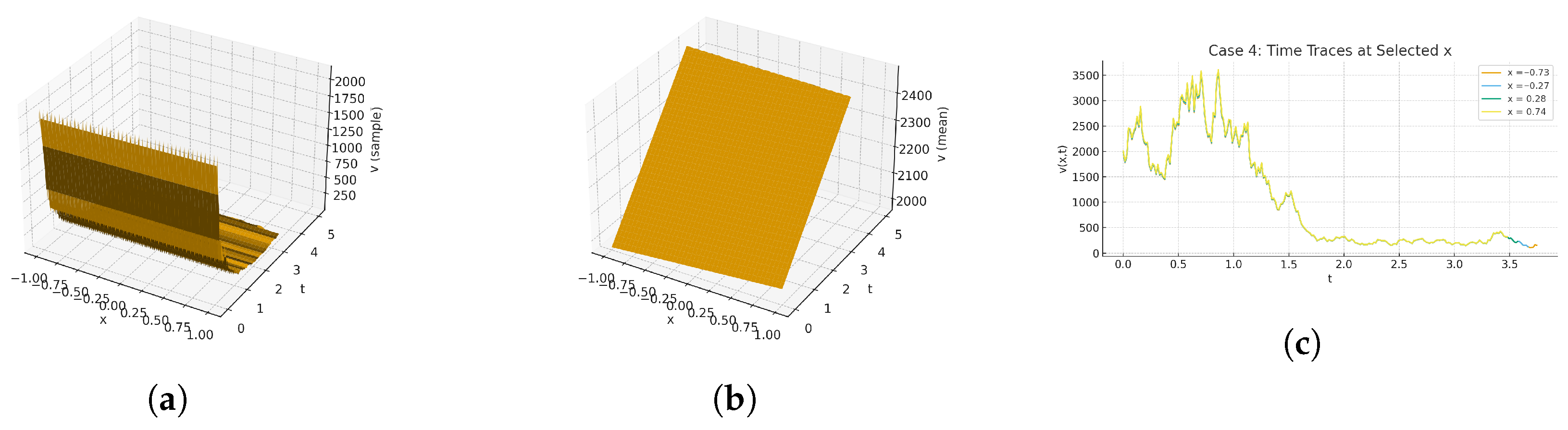

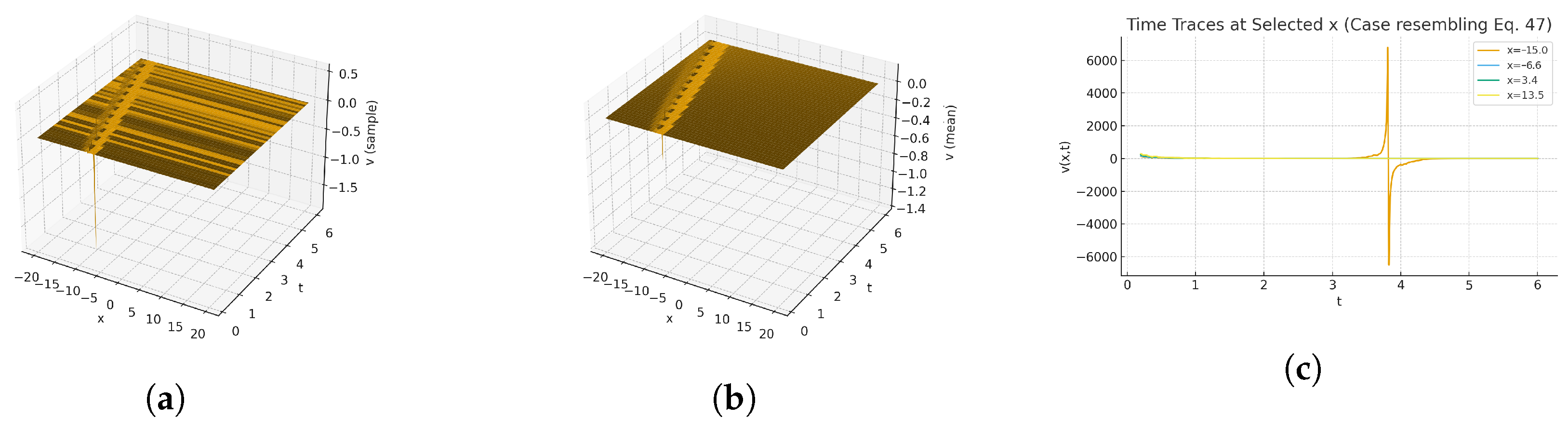

| PresentStudy | Stochastic Kairat-II and Kairat-X (3 + 1D) | Wiener process modeling; modified auxiliary eq.; energy balance | 3D surfaces, sample path vs. mean-field plots, time traces; EBA validation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rizvi, S.T.R.; Jlali, L.; Anjum, I.; Abad, H.; Solouma, E.; Seadawy, A.R. Nonlinear Stochastic Wave Behavior: Soliton Solutions and Energy Analysis of Kairat-II and Kairat-X Systems. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110728

Rizvi STR, Jlali L, Anjum I, Abad H, Solouma E, Seadawy AR. Nonlinear Stochastic Wave Behavior: Soliton Solutions and Energy Analysis of Kairat-II and Kairat-X Systems. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(11):728. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110728

Chicago/Turabian StyleRizvi, Syed T. R., Lotfi Jlali, Iqra Anjum, Husnain Abad, Emad Solouma, and Aly R. Seadawy. 2025. "Nonlinear Stochastic Wave Behavior: Soliton Solutions and Energy Analysis of Kairat-II and Kairat-X Systems" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 11: 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110728

APA StyleRizvi, S. T. R., Jlali, L., Anjum, I., Abad, H., Solouma, E., & Seadawy, A. R. (2025). Nonlinear Stochastic Wave Behavior: Soliton Solutions and Energy Analysis of Kairat-II and Kairat-X Systems. Fractal and Fractional, 9(11), 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110728